Cedric himself knew

nothing whatever about it. It had never been even mentioned to him.

He knew that his papa had been an Englishman, because his mamma had

told him so; but then his papa had died when he was so little a boy

that he could not remember very much about him, except that he was

big, and had blue eyes and a long mustache, and that it was a

splendid thing to be carried around the room on his shoulder. Since

his papa's death, Cedric had found out that it was best not to talk

to his mamma about him. When his father was ill, Cedric had been

sent away, and when he had returned, everything was over; and his

mother, who had been very ill, too, was only just beginning to sit

in her chair by the window. She was pale and thin, and all the

dimples had gone from her pretty face, and her eyes looked large

and mournful, and she was dressed in black.

“Dearest,” said Cedric (his papa

had called her that always, and so the little boy had learned to

say it),—“dearest, is my papa better?”

He felt her arms tremble, and so

he turned his curly head and looked in her face. There was

something in it that made him feel that he was going to cry.

“Dearest,” he said, “is he

well?”

Then suddenly his loving little

heart told him that he'd better put both his arms around her neck

and kiss her again and again, and keep his soft cheek close to

hers; and he did so, and she laid her face on his shoulder and

cried bitterly, holding him as if she could never let him go

again.

“Yes, he is well,” she sobbed;

“he is quite, quite well, but we—we have no one left but each

other. No one at all.”

Then, little as he was, he

understood that his big, handsome young papa would not come back

any more; that he was dead, as he had heard of other people being,

although he could not comprehend exactly what strange thing had

brought all this sadness about. It was because his mamma always

cried when he spoke of his papa that he secretly made up his mind

it was better not to speak of him very often to her, and he found

out, too, that it was better not to let her sit still and look into

the fire or out of the window without moving or talking. He and his

mamma knew very few people, and lived what might have been thought

very lonely lives, although Cedric did not know it was lonely until

he grew older and heard why it was they had no visitors. Then he

was told that his mamma was an orphan, and quite alone in the world

when his papa had married her. She was very pretty, and had been

living as companion to a rich old lady who was not kind to her, and

one day Captain Cedric Errol, who was calling at the house, saw her

run up the stairs with tears on her eyelashes; and she looked so

sweet and innocent and sorrowful that the Captain could not forget

her. And after many strange things had happened, they knew each

other well and loved each other dearly, and were married, although

their marriage brought them the ill-will of several persons. The

one who was most angry of all, however, was the Captain's father,

who lived in England, and was a very rich and important old

nobleman, with a very bad temper and a very violent dislike to

America and Americans. He had two sons older than Captain Cedric;

and it was the law that the elder of these sons should inherit the

family title and estates, which were very rich and splendid; if the

eldest son died, the next one would be heir; so, though he was a

member of such a great family, there was little chance that Captain

Cedric would be very rich himself.

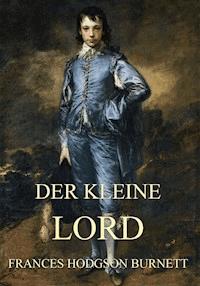

But it so happened that Nature

had given to the youngest son gifts which she had not bestowed upon

his elder brothers. He had a beautiful face and a fine, strong,

graceful figure; he had a bright smile and a sweet, gay voice; he

was brave and generous, and had the kindest heart in the world, and

seemed to have the power to make every one love him. And it was not

so with his elder brothers; neither of them was handsome, or very

kind, or clever. When they were boys at Eton, they were not

popular; when they were at college, they cared nothing for study,

and wasted both time and money, and made few real friends. The old

Earl, their father, was constantly disappointed and humiliated by

them; his heir was no honor to his noble name, and did not promise

to end in being anything but a selfish, wasteful, insignificant

man, with no manly or noble qualities. It was very bitter, the old

Earl thought, that the son who was only third, and would have only

a very small fortune, should be the one who had all the gifts, and

all the charms, and all the strength and beauty. Sometimes he

almost hated the handsome young man because he seemed to have the

good things which should have gone with the stately title and the

magnificent estates; and yet, in the depths of his proud, stubborn

old heart, he could not help caring very much for his youngest son.

It was in one of his fits of petulance that he sent him off to

travel in America; he thought he would send him away for a while,

so that he should not be made angry by constantly contrasting him

with his brothers, who were at that time giving him a great deal of

trouble by their wild ways.

But, after about six months, he

began to feel lonely, and longed in secret to see his son again, so

he wrote to Captain Cedric and ordered him home. The letter he

wrote crossed on its way a letter the Captain had just written to

his father, telling of his love for the pretty American girl, and

of his intended marriage; and when the Earl received that letter he

was furiously angry. Bad as his temper was, he had never given way

to it in his life as he gave way to it when he read the Captain's

letter. His valet, who was in the room when it came, thought his

lordship would have a fit of apoplexy, he was so wild with anger.

For an hour he raged like a tiger, and then he sat down and wrote

to his son, and ordered him never to come near his old home, nor to

write to his father or brothers again. He told him he might live as

he pleased, and die where he pleased, that he should be cut off

from his family forever, and that he need never expect help from

his father as long as he lived.

The Captain was very sad when he

read the letter; he was very fond of England, and he dearly loved

the beautiful home where he had been born; he had even loved his

ill-tempered old father, and had sympathized with him in his

disappointments; but he knew he need expect no kindness from him in

the future. At first he scarcely knew what to do; he had not been

brought up to work, and had no business experience, but he had

courage and plenty of determination. So he sold his commission in

the English army, and after some trouble found a situation in New

York, and married. The change from his old life in England was very

great, but he was young and happy, and he hoped that hard work

would do great things for him in the future. He had a small house

on a quiet street, and his little boy was born there, and

everything was so gay and cheerful, in a simple way, that he was

never sorry for a moment that he had married the rich old lady's

pretty companion just because she was so sweet and he loved her and

she loved him. She was very sweet, indeed, and her little boy was

like both her and his father. Though he was born in so quiet and

cheap a little home, it seemed as if there never had been a more

fortunate baby. In the first place, he was always well, and so he

never gave any one trouble; in the second place, he had so sweet a

temper and ways so charming that he was a pleasure to every one;

and in the third place, he was so beautiful to look at that he was

quite a picture. Instead of being a bald-headed baby, he started in

life with a quantity of soft, fine, gold-colored hair, which curled

up at the ends, and went into loose rings by the time he was six

months old; he had big brown eyes and long eyelashes and a darling

little face; he had so strong a back and such splendid sturdy legs,

that at nine months he learned suddenly to walk; his manners were

so good, for a baby, that it was delightful to make his

acquaintance. He seemed to feel that every one was his friend, and

when any one spoke to him, when he was in his carriage in the

street, he would give the stranger one sweet, serious look with the

brown eyes, and then follow it with a lovely, friendly smile; and

the consequence was, that there was not a person in the

neighborhood of the quiet street where he lived—even to the

groceryman at the corner, who was considered the crossest creature

alive—who was not pleased to see him and speak to him. And every

month of his life he grew handsomer and more interesting.

When he was old enough to walk

out with his nurse, dragging a small wagon and wearing a short

white kilt skirt, and a big white hat set back on his curly yellow

hair, he was so handsome and strong and rosy that he attracted

every one's attention, and his nurse would come home and tell his

mamma stories of the ladies who had stopped their carriages to look

at and speak to him, and of how pleased they were when he talked to

them in his cheerful little way, as if he had known them always.

His greatest charm was this cheerful, fearless, quaint little way

of making friends with people. I think it arose from his having a

very confiding nature, and a kind little heart that sympathized

with every one, and wished to make every one as comfortable as he

liked to be himself. It made him very quick to understand the

feelings of those about him. Perhaps this had grown on him, too,

because he had lived so much with his father and mother, who were

always loving and considerate and tender and well-bred. He had

never heard an unkind or uncourteous word spoken at home; he had

always been loved and caressed and treated tenderly, and so his

childish soul was full of kindness and innocent warm feeling. He

had always heard his mamma called by pretty, loving names, and so

he used them himself when he spoke to her; he had always seen that

his papa watched over her and took great care of her, and so he

learned, too, to be careful of her.

So when he knew his papa would

come back no more, and saw how very sad his mamma was, there

gradually came into his kind little heart the thought that he must

do what he could to make her happy. He was not much more than a

baby, but that thought was in his mind whenever he climbed upon her

knee and kissed her and put his curly head on her neck, and when he

brought his toys and picture-books to show her, and when he curled

up quietly by her side as she used to lie on the sofa. He was not

old enough to know of anything else to do, so he did what he could,

and was more of a comfort to her than he could have

understood.

“Oh, Mary!” he heard her say once

to her old servant; “I am sure he is trying to help me in his

innocent way—I know he is. He looks at me sometimes with a loving,

wondering little look, as if he were sorry for me, and then he will

come and pet me or show me something. He is such a little man, I

really think he knows.”

As he grew older, he had a great

many quaint little ways which amused and interested people greatly.

He was so much of a companion for his mother that she scarcely

cared for any other. They used to walk together and talk together

and play together. When he was quite a little fellow, he learned to

read; and after that he used to lie on the hearth-rug, in the

evening, and read aloud—sometimes stories, and sometimes big books

such as older people read, and sometimes even the newspaper; and

often at such times Mary, in the kitchen, would hear Mrs. Errol

laughing with delight at the quaint things he said.

“And, indade,” said Mary to the

groceryman, “nobody cud help laughin' at the quare little ways of

him—and his ould-fashioned sayin's! Didn't he come into my kitchen

the noight the new Prisident was nominated and shtand afore the

fire, lookin' loike a pictur', wid his hands in his shmall pockets,

an' his innocent bit of a face as sayrious as a jedge? An' sez he

to me: 'Mary,' sez he, 'I'm very much int'rusted in the 'lection,'

sez he. 'I'm a 'publican, an' so is Dearest. Are you a 'publican,

Mary?' 'Sorra a bit,' sez I; 'I'm the bist o' dimmycrats!' An' he

looks up at me wid a look that ud go to yer heart, an' sez he:

'Mary,' sez he, 'the country will go to ruin.' An' nivver a day

since thin has he let go by widout argyin' wid me to change me

polytics.”

Mary was very fond of him, and

very proud of him, too. She had been with his mother ever since he

was born; and, after his father's death, had been cook and

housemaid and nurse and everything else. She was proud of his

graceful, strong little body and his pretty manners, and especially

proud of the bright curly hair which waved over his forehead and

fell in charming love-locks on his shoulders. She was willing to

work early and late to help his mamma make his small suits and keep

them in order.

“'Ristycratic, is it?” she would

say. “Faith, an' I'd loike to see the choild on Fifth Avey-NOO as

looks loike him an' shteps out as handsome as himself. An' ivvery

man, woman, and choild lookin' afther him in his bit of a black

velvet skirt made out of the misthress's ould gownd; an' his little

head up, an' his curly hair flyin' an' shinin'. It's loike a young

lord he looks.”

Cedric did not know that he

looked like a young lord; he did not know what a lord was. His

greatest friend was the groceryman at the corner—the cross

groceryman, who was never cross to him. His name was Mr. Hobbs, and

Cedric admired and respected him very much. He thought him a very

rich and powerful person, he had so many things in his

store,—prunes and figs and oranges and biscuits,—and he had a horse

and wagon. Cedric was fond of the milkman and the baker and the

apple-woman, but he liked Mr. Hobbs best of all, and was on terms

of such intimacy with him that he went to see him every day, and

often sat with him quite a long time, discussing the topics of the

hour. It was quite surprising how many things they found to talk

about—the Fourth of July, for instance. When they began to talk

about the Fourth of July there really seemed no end to it. Mr.

Hobbs had a very bad opinion of “the British,” and he told the

whole story of the Revolution, relating very wonderful and

patriotic stories about the villainy of the enemy and the bravery

of the Revolutionary heroes, and he even generously repeated part

of the Declaration of Independence.

Cedric was so excited that his

eyes shone and his cheeks were red and his curls were all rubbed

and tumbled into a yellow mop. He could hardly wait to eat his

dinner after he went home, he was so anxious to tell his mamma. It

was, perhaps, Mr. Hobbs who gave him his first interest in

politics. Mr. Hobbs was fond of reading the newspapers, and so

Cedric heard a great deal about what was going on in Washington;

and Mr. Hobbs would tell him whether the President was doing his

duty or not. And once, when there was an election, he found it all

quite grand, and probably but for Mr. Hobbs and Cedric the country

might have been wrecked.

Mr. Hobbs took him to see a great

torchlight procession, and many of the men who carried torches

remembered afterward a stout man who stood near a lamp-post and

held on his shoulder a handsome little shouting boy, who waved his

cap in the air.

It was not long after this

election, when Cedric was between seven and eight years old, that

the very strange thing happened which made so wonderful a change in

his life. It was quite curious, too, that the day it happened he

had been talking to Mr. Hobbs about England and the Queen, and Mr.

Hobbs had said some very severe things about the aristocracy, being

specially indignant against earls and marquises. It had been a hot

morning; and after playing soldiers with some friends of his,

Cedric had gone into the store to rest, and had found Mr. Hobbs

looking very fierce over a piece of the Illustrated London News,

which contained a picture of some court ceremony.

“Ah,” he said, “that's the way

they go on now; but they'll get enough of it some day, when those

they've trod on rise and blow 'em up sky-high,—earls and marquises

and all! It's coming, and they may look out for it!”

Cedric had perched himself as

usual on the high stool and pushed his hat back, and put his hands

in his pockets in delicate compliment to Mr. Hobbs.

“Did you ever know many

marquises, Mr. Hobbs?” Cedric inquired,—“or earls?”

“No,” answered Mr. Hobbs, with

indignation; “I guess not. I'd like to catch one of 'em inside

here; that's all! I'll have no grasping tyrants sittin' 'round on

my cracker-barrels!”

And he was so proud of the

sentiment that he looked around proudly and mopped his

forehead.

“Perhaps they wouldn't be earls

if they knew any better,” said Cedric, feeling some vague sympathy

for their unhappy condition.

“Wouldn't they!” said Mr. Hobbs.

“They just glory in it! It's in 'em. They're a bad lot.”

They were in the midst of their

conversation, when Mary appeared.

Cedric thought she had come to

buy some sugar, perhaps, but she had not. She looked almost pale

and as if she were excited about something.

“Come home, darlint,” she said;

“the misthress is wantin' yez.”

Cedric slipped down from his

stool.

“Does she want me to go out with

her, Mary?” he asked. “Good-morning, Mr. Hobbs. I'll see you

again.”

He was surprised to see Mary

staring at him in a dumfounded fashion, and he wondered why she

kept shaking her head.

“What's the matter, Mary?” he

said. “Is it the hot weather?”

“No,” said Mary; “but there's

strange things happenin' to us.”

“Has the sun given Dearest a

headache?” he inquired anxiously.

But it was not that. When he

reached his own house there was a coupe standing before the door

and some one was in the little parlor talking to his mamma. Mary

hurried him upstairs and put on his best summer suit of

cream-colored flannel, with the red scarf around his waist, and

combed out his curly locks.

“Lords, is it?” he heard her say.

“An' the nobility an' gintry. Och! bad cess to them! Lords,

indade—worse luck.”

It was really very puzzling, but

he felt sure his mamma would tell him what all the excitement

meant, so he allowed Mary to bemoan herself without asking many

questions. When he was dressed, he ran downstairs and went into the

parlor. A tall, thin old gentleman with a sharp face was sitting in

an arm-chair. His mother was standing near by with a pale face, and

he saw that there were tears in her eyes.

“Oh! Ceddie!” she cried out, and

ran to her little boy and caught him in her arms and kissed him in

a frightened, troubled way. “Oh! Ceddie, darling!”

The tall old gentleman rose from

his chair and looked at Cedric with his sharp eyes. He rubbed his

thin chin with his bony hand as he looked.

He seemed not at all

displeased.

“And so,” he said at last,

slowly,—“and so this is little Lord Fauntleroy.”