1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Constance is used to getting what she wants. But when she finally meets a man she can't control, her self-centered life is turned upside down!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

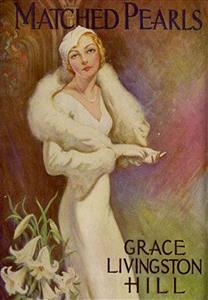

Matched Pearls

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1933

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

Constance Courtland came smiling into the living room humming a cheerful little tune. She had just been lingering at the front door with Rudyard Van Arden, a neighbor’s son whom she had gone for a drive with, and her brother.

Frank looked up with a whimsical sneer.

“Well, has that egg gone home at last?” he drawled. “It beats me what you find to say to him. You’ve been gassing out there for a full half hour. Why, I c’n remember when you wouldn’t speak ta that guy. You said he was the limit. And now just because you’ve both been ta college, and he’s got a sweater with a big red letter on the front and a little apricot-colored eyebrow on his upper lip, you stand there and chew the rag fer half an hour. And Mother, here, ben having seven pink fits for fear the Reverend Gustawvus Grant’ll return before she has a chance ta give ya the high sign.”

The mother rose hurriedly, embarrassedly, her face flushing guiltily, and began to protest.

“Really, Frank, you have no right to talk to your sister that way about her friends! When she’s only home for this weekend, you ought to make it as pleasant for her as you can. You don’t see much of your sister, and you oughtn’t to tease her like that. She won’t carry a very pleasant memory of her home back to college if you annoy her so whenever one of the old neighbors comes in to see her a little while. You know perfectly well that Rudyard Van Arden is a fine, respectable young man.”

Constance stopped humming and looked keenly from her brother to her mother.

“Never mind Ruddy Van,” she said, coolly sweeping her mother’s words aside without ceremony. “What’s this about Dr. Grant? You don’t mean to tell me, Mother, that you’ve invited him to dinner one of the few nights I have at home, when you know how I detest him?”

“No, of course not, dear!” said the mother hastily and placatingly. “Nothing like that at all. He just dropped in to see you this afternoon. He was very anxious to talk with you—” The mother stopped abruptly.

“To talk with me!” said Constance, narrowing her eyes and looking from mother to brother again. “What could he possibly want to talk with me about? If it’s to sing in the Easter choir or a solo, no, I won’t and that’s flat! I can’t and won’t sing with that Ferran girl flatting the way she does. There’s no use asking me. If that’s what he wants I’ll slide out the back way and go over to Mabel’s for a little while. You just tell him I’ve got bronchitis or any other efficient throat trouble. I simply won’t discuss it with him. He always acts as if he wants to chuck me under the chin or pat me on the head as if I was still five. My, how I used to hate it!”

“No, dear, it’s nothing like that. He didn’t even suggest your singing.”

“Well then, what is it? Let’s get it over with.”

“Why, dear, you see they’re having a special communion service tomorrow—Easter, you know. It’s such a lovely idea, and all your Sunday school class are uniting with the church. He wanted you to join with them and make it a full class. It seems a rather lovely idea, I think myself, so suitable, you know.”

“Me? Join the church? Oh, Mother! How Victorian!”

“Oh but now, Constance, don’t try to be modern. No, wait! I really have got to tell you about it, because he may be here any minute now, and Connie dear, your grandmother has quite set her heart upon it.”

“Grandmother!” laughed Constance. “What has she got to do with it? My soul! It sounds as if my family were still in the dark ages.”

“Well, but Connie, you’ll find your grandmother is very much upset about it. You see she’s been scolding me ever since you first went off to college that I let you go without uniting with the church. She thought it would be such a safeguard. And now that you’ve almost finished, she is determined that you shall be a member of the church before you graduate. She says she did and I did and it isn’t respectable not to. And really, my dear, I think you’ll just have to put your own wishes aside this time and humor her.”

“How ridiculous, Mother. Join the church to suit Grandmother! Just you leave her to me. I’ll make her understand that girls don’t do things like that today. Things are different from when she was young. And by the way, Mother, do you think she’s going to give me that string of pearls for a graduating present? You promised to feel around and see. I’d so much like to have it for the big dance next week. It’s going to be a swell affair.”

“Well, that’s the trouble, Constance dear. I’ve been trying to find out what she had planned, and it seems she’s quite got her heart set on that string of pearls being a present to you when you join the church. Her father gave it to her when she joined, and she has often said to me, ‘The day that Constance joins the church I shall give her my string of pearls.’ I really believe she means it, too, for she has been talking about your cousin Norma, and once she asked me if Norma was a member of the church.”

“Mercy, Mother, you don’t think she’s thinking of giving a string of matched pearls to a little country school teacher with a muddy complexion and no place in the world to wear them?”

“You can’t tell, my dear, what she may not do if you frustrate her in this desire of her heart. She’s just determined, Connie! She told me your grandfather had always said that he wanted to see you a member of the old church and be sure you were safe in the fold before he died, and she had sort of given him her word that she would see to it that you came out all right. Connie, you really mustn’t laugh so loud. If she were to hear you—!”

Constance stifled her mirth.

“But honestly, Mother, it’s so Victorian, so sort of traditional and all, you know. I’d be ashamed to have it get back to college that I had to knuckle in and join the church to please my grandmother. Why, everybody would despise me after the enlightening education I’ve had. It’s a sort of relic of the dark ages.”

“Aw, you don’t havta believe anything,” put in the brother amusedly. “Just havta stand up there a few minutes and then it’s all over. Doesn’t mean a thing, and who’ll ever think of it again? Gee, if Grandmother’d buy me that Rolls-Royce I want, I’d join the church any day! I don’t see whatcha making sucha fuss about.”

“Franklin! That’s irreverent!” reproved his mother coldly. “Of course Constance would do anything she did sincerely. Constance has always been conscientious. But, Connie dear, I don’t see why you object to something that has been a tradition in the family for years. Of course you’re a thoughtless girl now, but you’ll come to a time when you’ll be glad you did it, something to depend on in times of trouble and all that. You know, really, it’s a good thing to get a matter like this all settled when one is young. And of course, you know, that college-girl point of view isn’t always going to stay with you. You just think you’ve got new light on things now, but when you get older and settle down you’ll see the church was a good, safe place to be.”

“Oh applesauce!” said Constance merrily. “Mother, what good has it ever done you to be a member of a church, I’d like to know? Oh, of course you’ve pussyfooted through all their missionary tea-fights and things like that, and everybody puts you on committees and things. You may like that sort of thing, but I don’t. I never could stand going to church, and as for Dr. Grant, I can’t endure his long, monotonous preaching! No, really, Mother, I can’t! Let me talk to Grandmother. I’m sure I can make her see this thing straight.”

“No, Constance, really you mustn’t talk to your grandmother! Indeed, my child, you don’t understand. She’s quite in a critical state. I’m not sure but she contemplates writing Norma this evening and committing herself about those pearls. She feels that religion is being insulted by your not uniting with the old family church. And you know, my dear, in spite of all the modern talk, one really does need a little religion in life.”

“That is nothing but sentimental slush!” said Constance indignantly.

“Well, I’ll grant you your grandmother is a trifle sentimental about those pearls,” admitted the mother. “She feels that they are a sort of symbol of innocence and religion. She said all those things this afternoon. In fact, I’d been having a rather dreadful time with her ever since Dr. Grant called, until I told her that he was returning to arrange things with you and I was quite sure you would be willing to see things as she wanted you to.”

“Oh, Mother!”

“There’s the reverend gentleman now,” said Frank amusedly, gathering up his long legs from the couch where he had been stretched during the colloquy. “I’m going ta beat it. He hasn’t got a line on me yet, not until Grand talks about that Rolls-Royce, anyway.”

“Oh, Mother, I really can’t stay and see him. Let me get up the back stairs quick,” said Constance.

But her mother placed her substantial body firmly in her path.

“No, Constance, I must insist! This really is a serious matter. You are not going to let those ancestral pearls go out of the immediate family, I am sure. Listen, Connie, he’s merely coming to arrange a time for you to meet the session. It’s only a formality, you know, just a question or two and it’s over. There won’t be time for anything else. He said the session has a meeting this evening. Some of the girls will be there then.”

“Indeed I can’t go this evening,” blustered Constance breathlessly. “I’m going to that dance at the country club, and I promised Ruddy I’d ride with him in his new car beforehand.”

“Well, we’ll fix it somehow. Tomorrow morning you could go a little early, before the service. It’s only a formality anyway.”

“Oh, Mother!” wailed Constance softly as she slipped through the door. “I was going to play golf with Ruddy all tomorrow morning! Must I, Mother? Can’t I get by without it?”

“I’m afraid you must, dear,” said her mother firmly, even while she arranged a welcoming smile on her lips for the old minister who was being ushered in.

With a whispered moan, Constance had slipped up the back way to her room, where she remained during the minister’s stay.

As Constance answered the call to dinner ten minutes after the minister’s departure, she saw her mother and her grandmother at the foot of the front stairs talking.

“It’s all right, Mother dear. Constance is going to join,” said Constance’s mother to the firm-mouthed, little old lady in black silk with priceless lace at her throat and wrists.

The little old lady had keen black eyes, and she fixed them on her daughter warily.

“You’re sure she’s doing it of her own free will, Mary?” she asked. “I wouldn’t want any pressure to be brought to bear upon her in a thing like this.”

“Oh yes, Mother dear, I’m quite sure Constance sees the fitness of it all. Easter Sunday, too—so appropriate!”

Relief came in the bright eyes; the tenseness of the thin lips relaxed.

“Then she’ll meet the session tonight?” she asked eagerly.

“Well, not tonight,” said the mother warily. “Dr. Grant has arranged a special session meeting early in the morning before the service.”

“Oh,” said Grandmother suspiciously. “Why was that?”

“Well, he said they often did,” evaded Constance’s mother. “I think it’s most appropriate at that hour just before the service.”

The old lady studied her daughter a moment speculatively; then, apparently satisfied, she said, “Well then, I shall give her the pearls in the morning. I’d like her to wear them to the service. I’d like to see them on her the first time in the church. Easter Day. Her first communion. It will be lovely, Mary. It will be just as I have hoped and planned. Her grandfather would have liked it so.”

“Yes!” said Constance’s mother crisply. “So appropriate! And so dear of you, Mother, to give her the pearls. I’m sure she’ll be deeply grateful.”

Constance smothered a mocking smile and came ruefully down the stairs, wondering what some of her professors at college and various fellow students would think if they would know that she was succumbing to tradition and family pressure just for a string of pearls. Well, the pearls were worth it! Matched pearls and flawless. The only really worthwhile heirloom in the family. Grandfather’s taste in adornment had been severe simplicity and pearls!

The sun shone forth gorgeously on Easter morning. Constance groaned softly as she saw it, looked out from her window and noted the far stretch of the golf links in the distance. Such a day as this was meant to play golf! And to think all the morning had to be wasted!

Yet of course she was to wear the string of pearls!

She went about her dressing with more than the usual care. Was she not to be the focus of all eyes today? Even the eyes in a country church, which had been her great-grandfather’s church in the past, were worth dressing for.

She picked her garments all of white—heavy white silk with a long, fitted coat, white furred to match, white shoes, even white stockings, though the suntan would have been more stylish, but she must not have the look of a sportsman this morning. Grandmother was even capable of coming right up to the front and taking those pearls off her neck during the service if she suspected all was not utmost innocence.

She dressed her golden hair demurely in smooth braids coiled low over her ears with a little tip-tilted hat of white showing a few soft waves on her forehead. With her gold hair, the white hat, and sweet untinted cheeks and lips au naturel for the occasion, she looked like some young saint set apart from all the world.

Her grandmother felt it when she came down the stairs and met her with a sacred smile and a look of satisfaction in the keen, eager old eyes. She clasped the pearls around Constance’s neck and kissed her tenderly.

“Dear child!” she whispered. “How your grandfather used to talk about this day and pray about it!” And then, half-frightened at her words, she retreated back into her silent reticence and hurried out the door to where the car waited to take them to church.

And Constance, following, felt a sudden smart of tears in her eyes in spite of her cynicism. She remembered the words of one most modern professor in talking once about sacraments—how he had advised them not to throw away old sacraments, even if they meant nothing anymore, but to keep them for the sweet sentiment they had had in former years. Constance thought she understood suddenly what he had meant. She caught a brief vision of what all this meant to her grandmother and was really glad she had done it. Even without the pearls, she was glad she had done it just to please little, sweet, hard, bright, old Grandmother.

So with virtue shining from her lovely ultramarine eyes, she entered the lily-decked aisles and took her place in the house of the Lord.

The windows in the old, old church were lovely Tiffany windows. They cast opalescent lights across the sanctuary and touched lightly like a halo the gold of Constance’s hair. They lighted up her unpainted face till she attained an almost holy look in her white garments, her gold hair, her blue, blue eyes, and the pearls around her neck with twinkles of the beauties of all the world in their polished depths.

The music was angelic, and the words the monotonous old minister read and said were sonorous and musical. They meant nothing much to Constance. She was seeing herself with the pearls at the next weekend party. She was conscious of the crowded sanctuary and of being the best dressed of the whole class of which she was a member.

When the time came, she went sweetly, demurely up to the front of the church and stood with just such a prayerful attitude as did her grandmother years and years before, and people whispered, “Isn’t Constance lovely? I never knew she was so serious, did you?”

Constance stood before the altar and kept her eyes upon the white-haired Dr. Grant, whom she detested, watching his lips half-fascinated, wondering if the wave in his white hair was natural, bowing her head when the prayer began, and studying the toes of two well-polished shoes and the neat creases of the cheap, dark blue serge trousers that stood next to her white suede shoes, and wondering idly who was their owner. Was the serge a bit shiny, almost shabby? That was the impression she got from her brief glance as she closed her eyes for the prayer.

The ceremony was over and they were seated for the sacrament. Constance noticed as she sat down that the man beside her was tall and had a courteous bearing. She had not noticed his name as it was called. Doubtless some newcomer since she had been away.

The solemn ceremony proceeded amid soft music from the fine organ; tender old melodies that reminded her of her childhood days; exquisite fragrance from the lilies in the chancel; blended prisms of color flung across the perfumed air from the Tiffany windows; scraps of white bread on silver plates; tiny, tinkling crystal glasses like ruby jewels passing; blood-red wine against the whiteness of the lilies in the chancel; soft, cool polish of matched pearls against the softness of her neck. It all was a lovely dream to Constance, just a picture in which the colors and setting harmonized. It meant nothing in her life, a brief incident and pearls. What did it matter if she had the pearls for her very own? She had a passing moment of wonder as she touched the tiny glass of wine to her lips. Memory flashed back to a Sunday long ago when she had wept bitterly into her grandmother’s lap that she could not have this privilege, and now here it was hers and she was reluctant. Was all life like that? She wondered. Nothing attained until desire had passed!

At last the final solemn march and passing of the mystic symbols was complete; the painful stillness, soft-music-laden, was over; the final hymn and benediction finished; the minister admonished the members to greet one another with a cordial right hand of fellowship before they left; and the organ burst forth into a triumphal Easter paean of victory.

Constance lifted up her head with a relieved breath and glanced around her. She was free now for the rest of the day. Her penance was over and the prize was upon her.

Then a voice beside and above her spoke, a pleasant, confidential voice that yet was clear above the trumpeting of the organ, with something throbbing, deep and stirring, in its lilt.

“I guess that means that we’re to greet one another, doesn’t it?” the voice asked. “We’re members of one household now, members of the Body of Christ.”

Then Constance was aware of a hand, shapely, well cared for as a woman’s, yet firm, big, strong, the hand of a real man. And it was obviously being held out to her in greeting, a kind of holy greeting, it seemed. She was suddenly aware that all the people around her were shaking hands and offering congratulations, just like a wedding reception! Heavens! Did one have to endure another ordeal also? And who was this presumptuous person who seemed determined to shake hands with her? A stranger!

She lifted haughty eyes and met the handsomest brown eyes she had ever looked into, young, friendly, pleasant eyes; and then without her own volition she found her hand folded in a strong, quick clasp.

The stranger was taking almost reverent note of the sweet line of forehead under gold hair and little tilted hat brim, lovely curve of cheek and lip and chin, the soft white neck above the lustrous pearls, and doing them homage with his glance.

“My name is Seagrave. May I know yours?” he asked with utmost courtesy.

Then Constance remembered her patrician birth, the pearls she wore so regally, the shabbiness of the blue serge trousers she had glimpsed through prayer time, and lifted her chin, stiffening visibly, and answering in a voice like a clear, lovely icicle. “I am Miss Courtland.”

“Thank you, Miss Courtland. I am glad to know you,” he said with quaint, old-time formality. “I hope we’ll meet again.”

Constance gave him a little, frozen smile and swept him an upward appraising glance.

“I’m afraid not,” she said haughtily. “I’m going back to college Tuesday.”

Their glances met for just an instant, a puzzled questioning gaze, and then her girl friends surged between them; when she looked again, wondering if she must introduce him, he was gone.

“Who’s your boyfriend, Con?” whispered Rose Acker, one of her most intimate friends. “Isn’t he perfectly stunning looking!”

But Constance only smiled and went forward to her grandmother who was waiting with proud eyes and sternly pleasant lips.

As they drove along in the car toward home, Constance looked for the stranger among the people on the pavement, but he was not anywhere among them. She wondered if she would ever see him again. He was impertinent of course, or perhaps only ignorant, she decided, but nevertheless interesting. A new type.

“Well,” said her brother, Frank, coming down the steps to fling open the car door for them when they reached home, “is the grand agony over?”

“Do you see my lovely pearls?” asked Constance quickly with a warning look at her brother as she noted the wicked twinkle in his eyes.

“Some pearls!” said the reckless youth. “Cheap at the price, I’ll say! What do I get, Grand, if I go and do the same sometime?”

But the little old lady with the keen dark eyes shut her thin lips in a firm line and spurned her grandson’s offered arm, tripping up the steps like an indignant robin, holding her black taffeta shoulders irately as she marched into the house without answering.

Chapter 2

Constance came downstairs early the next morning. She had promised to play a set of tennis with Ruddy Van Arden. She wanted to get in touch with the brightness of the morning and stretch her wings a little just to feel how good it was to be at home again.

Her father and mother were not down yet, breakfast wasn’t ready, and Frank, of course, would not even be awake. Perhaps she would go up and lay a nice cool, dripping washcloth across his eyes and forehead and call good morning as she slipped away again, before he roused and threw it at her.

But first she would bring in the morning paper and just get a glimpse of the yard. She had caught a glimmer of daffodils down near the walk, and was the forsythia bush really out in bloom?

She opened the front door and picked up the paper, glanced idly over the headlines, then looked toward the daffodils. Yes, they were out. She would go down and look at them. So tucking the paper under the arm of her pretty, knitted dress of blue and white, she started across the lawn.

She was halfway down to the walk before she saw Seagrave coming up the street with something in his hands, carrying it wrapped in white like a cake. She paused, irresolute, the color coming to her cheeks, then hastened on. Why should it be anything to her that he was passing her father’s house? He was a stranger. She need not recognize him. It was not likely he would know her again, she told herself, and hurried down to where the daffodils made brave array along the path to the street.

Her face was down among the daffodils, pretending to be inhaling their delicate fragrance, her golden head among the golden flowers. The morning paper slid into the grass.

She heard his footsteps pass on the pavement and turn in at her father’s gate. Could it be possible that he would presume upon a mere church acquaintance? Would he dare? Her indignation grew. Now, she must say something to put him in his place. Yes, his steps were coming across the young spring grass, walking confidently and unafraid. What should she do? Freeze him? One would have thought that she had made it plain yesterday.

But now he paused above her, and his voice had again that soft, indescribable gentleness that strangely took away the idea of presumption in spite of her. Was it a touch of the South in his accent? She wasn’t sure. But there was a courtliness, a refinement about his voice that calmed her indignation and forced her attention.

“Good morning,” he said like a carefree boy. “I hardly hoped for such good luck as this. I’ve brought you something. I hope you don’t mind. You see you’re the only girl in town I know even a little, and this was too pretty to keep to myself.”

In amazement Constance straightened up and looked.

He was opening the white bundle that he carried like a cake, and now she saw it was his big clean handkerchief with the corners folded over, and it was full to the brim of the loveliest blue and white hepaticas, lying on a bed of delicate maidenhair fern. They were fresh with the dew upon them and they seemed as she looked to be the loveliest things that she had ever seen.

“Oh, the lovely things!” she exclaimed in wonder. “Wild-flowers! What are they? Where did you find them?”

“Aren’t they lovely?” he answered with eagerness. “Why, they are just hepaticas. I found them in the woods just over on that hill beyond the golf links. I’ve been out taking a little tramp and I came upon them. Isn’t our Lord wonderful to trouble to make such beautiful little things, and each one so perfect!”

Constance looked up at the young man and stared in wonder. She had no words to answer such a remark as this.

“I couldn’t help picking them,” he went on earnestly. “It seemed to me I must show them to someone else. I’m glad I found you. It seemed somehow as if they sort of belonged to you. They reminded me of you when I saw them.”

Constance did not know what to make of such homage as this. If he had said, “They’re not so bad, are they, old girl?” as some of her college acquaintances might have spoken freshly, she would have thought nothing of it, but this old-time courtesy and homage she did not understand. She wondered how he came to be that way and what she ought to do about it. She felt almost uncomfortable under such open yet reverent admiration.

“But you didn’t mean these for me,” she said, as if he were offering her priceless jewels that of course she could not be permitted to accept.

“If you’ll take them,” he said humbly. “I wouldn’t have any way of looking out for them myself now. I’m on my way to the office to get acquainted with my new job before things start off tomorrow. I’d hate to see the brave little things droop.”

Constance was filled with sudden pity for the flowers as if they had been lovely little children uncared for. His tone had invested them with personality.

“Oh, I’d love to have them,” she said quite simply now. He had been so humble she must put him at his ease. He had not meant to be presumptuous. He was just counting on that mystic bond of religion, that church stuff, probably. Strange a young man in these days could be so childlike. But he was probably brought up in the country. He would get over it.

“I don’t believe I ever saw them before,” she went on to cover her own embarrassment.

“I wish you could see them growing,” he said, watching her with unveiled admiration. “They’re like a little sea of blue, blowing and nodding in the grass, with these maidenhair ferns in a little huddle behind them like a miniature forest on the bank.”

“I’d like to see them,” she said frankly. “They must be a wonderful sight.”

“You couldn’t spare the time to go?” he asked wistfully. “I’d enjoy showing you just where they are.”

Constance glanced at her watch and shook her head.

“I have an appointment at the country club at nine.”

“Oh, not now,” he smiled. “I couldn’t go today at all. I thought perhaps tomorrow morning—early. Could you?”

“It would certainly have to be early,” laughed Constance and wondered why she dallied with this handsome, ingenuous boy. She had lost all sense of his being presumptuous now.

“I’m quite respectable, you know,” he said wistfully and flashed her a smile. “I could get Mr. Howarth to introduce us rightly. I’m with Howarth, Well and Company, you see—”

Constance flashed him a smile herself now. The Howarths were all right people. He must be respectable, she felt sure. Yet he was unusual, different from her other men friends. She wondered why she was interested.

“Could you go as early as half past five, or would six perhaps be better?” He fixed his brown eyes on her face now and gave her another of those radiant smiles, and suddenly she knew she was going to see those flowers tomorrow morning.

“I’m not sure,” she said thoughtfully. “If you are going anyway and happen to be passing by here about that time I might come along. I can’t really promise. Something might make it impossible.”

“Thank you,” he said with another of those grave smiles. “I’ll just be hoping. It’s very pleasant to have found a Christian friend right at the start in a strange place. I’m praising God for that. Now, I’ll bid you good morning. I must hurry to the office.”

Constance stood with the bundle of flowers in her hands and watched him walk away in wonder. What a strange, unusual young man he was. She had never seen anyone like him before. Heavens! How very good-looking he was. It seemed too good to be true, such looks on a man!

At the gate he turned and lifted his hat in a princely fashion. Constance stood still, smilingly nodded a friendly good-bye, and then wondered at herself.

It was not until he was out of sight that she realized that she was still holding his snowy handkerchief in her hands with its mound of ferns and flowers. Then suddenly her cheeks grew hot. Why had she been so very friendly as to let him give her flowers and promise to take a walk with him tomorrow morning when she had resolved before he came in to put him in a stranger’s place? Well, there was one thing, she didn’t have to go and take that walk. She wouldn’t, of course. She had left herself a loophole. She had not promised.

Then, with her cheeks still hot, she hurried into the house. She must get those flowers out of that handkerchief and the handkerchief out of sight before the family saw it.

She tipped the flowers into a large plate and stuffed the handkerchief quickly into her sleeve out of sight just as her brother, Frank, amazingly appeared in the dining room door.

“Who’s your comely giant, Connie?” he asked with a twinkle. “You certainly like ’em tall, don’t you?”

Constance looked up with a smile that was meant to be natural, but her cheeks were still hot and needed no rouge, and she knew that the watchful eyes of her brother would not let that little item pass.

“Oh, he’s just a man I met in church yesterday,” said Constance indifferently. “Fill that glass bowl with water for me, Frankie, that’s a dear.”

“Hmmm!” murmured Frank wisely as he returned from the butler’s pantry with the big crystal fruit bowl filled with water. “You only met him yesterday, and yet he gets up at all hours to pick doodads out of the woods for you! You certainly fetch ’em quick, don’t you, Sister?”

The color flew into Constance’s cheeks again to her great annoyance.

“Oh, for sweet mercy’s sake, won’t you stop being ridiculous? He happened to be passing and I admired them. Of course he had to give them to me.”

“Oh, was that the way it was?” mocked the imp of a brother. “I thought you were stooping down with your back to the street smelling daffodils when he went by and he had to come away around through the gate in the hedge and walk across the grass. But I must have been mistaken. Probably you called out to know what on earth he had done up in that handkerchief and he had to come in to show you. However, I should say in any case he was getting on fast.”

“Oh, shut up, will you?” said Constance, quite vexed and devoting herself to placing the airy stems in the fern-fringed bowl. The entrance of the rest of the family created a diversion, and Constance’s mother exclaimed over the beauty of the centerpiece.

“Wherever did you find them, dear?” she asked.

“Just an offering from one of her throng of admirers,” answered Frank quickly with an eloquent look. “They begin quite early in the morning, you perceive. I must wonder what it’s going to be like around here this summer if they come as thick as this in the spring.”

“Frank!” said his mother in a reproving tone. “You promised me last night you wouldn’t tease your sister anymore.”

Frank opened his eyes wide in wonder.

“Why, Muth dear, I wasn’t teasing. I was just admiring her tactics. She certainly has acquired good technique while she was at college.”

But Constance, with a murmur about washing her hands, hurried upstairs, and when she returned with coolly powdered cheeks and a placid exterior, her brother had somehow been subdued until only a pair of dancing eyes reminded her that he had not forgotten.

They sat down to breakfast, bowed their heads for the formal mumbling of a grace by the head of the house, the same old mumbled blessing he had used since Constance was a baby and his wife had told him it was not seemly to bring up children at a table without some sort of grace being said.

During the grapefruit and oatmeal, the passing of cream and sugar and hot rolls, the serving of eggs and bacon, there was pleasant conversation. Grandmother was not present. She took her breakfast in bed. They could speak about her freely.

“She was so pleased, Constance,” said Mary Courtland. “She’s been all strained up over this ever since she heard you were coming home at Easter and the girls in your class were all joining the church.”

“Well, I suppose it was an easy way to please her,” laughed the girl. “Of course I wasted the whole morning, but then it was worth it. Mother, it’s to be simply great having those pearls right now before college closes.”

“You forget, Connie,” put in Frank, “the comely giant. You wouldn’t have met him, remember, if you hadn’t gone to church. Pearls and a giant all in one morning. I’ll say the time wasn’t wasted even if poor Ruddy Van did have to cool his heels at the country club with Mildred Allison.”

But nobody was listening to Frank. His father was reading the morning paper, his sister acted as if he didn’t exist, and his mother went right on talking, deeming it the best way to get rid of the pest to just ignore him.

“You’ll have to be very careful about those pearls, you know, dear,” her mother warned Constance. “They are valuable, of course. Your grandmother will probably tell you before you leave just how valuable they are. You’d better arrange to keep them in the college safe. And be sure you don’t tell people indiscriminately that they are real. For really they are very valuable.”

“Yes, and Connie,” chimed Frank again in his nicest tone, “you better be careful about that good-looking giant, too.Hemight turn out to be valuable, you know. You never can tell when you have the real thing in a man right under your thumb, you know.”

Something in Constance’s mind clicked at that, but she went right on ignoring her brother, even though she did register a wonder whether he might not happen to be right concerning this particular young man.

Then Ruddy Van Arden slid up to the door in his new gray roadster, and Constance, with a breath of relief, hurried off after her racket and presently was gone into a great bright day of her own world. A world that had nothing to do with odd strangers who made odd remarks and gave lovely gifts of sweet wildflowers done up in fine linen handkerchiefs that smelled of lavender and had a hand-embroidered initial G in the corner.

All day long Constance enjoyed herself, playing tennis with Ruddy Van Arden in the morning, taking lunch at the country club with a party of young people, golf in the afternoon with Sam Acker from Harvard, then another eighteen holes with Ruddy to make up for Sunday morning, a hurried dinner at home with her stately little grandmother in black taffeta watching her across the table in her new rose evening frock and the pearls, a rush to the theater with a Mr. Montgomery whom she had met at luncheon and with whom she attended a play then late supper at a roof garden, and home long after midnight. Constance really had very little time to think of hepaticas and handsome, presumptuous strangers. The little hepaticas in their crystal bowl on the dining room table were all curled shut into sweet buds against the lacy green of the maidenhair when she stopped in the dining room for a drink of water before going up to her room. Little sleepy buds. Probably they would be dead in the morning. Flowers of a day. Like the handsome stranger-acquaintance of a morning.

As she tumbled into bed Constance remembered the half appointment for the morning. Half past five! Well, she never would make it now even if she wanted to, and of course she hadn’t meant to any of the time.

And then she fell asleep.

But strangely enough, a young early robin—or was it a starling or some other bird with a heavenly voice?—flew down on a twig beside her open window and trilled out a bit of celestial song just at a quarter past five. The clear sound dipped deep into her sleep and brought Constance back to earth and day again. She tried to turn over and go to sleep again, tried to tell herself that of course it was absurd to think of getting up at that hour and tramping off to the woods with an utter stranger who said and did odd things. But all the time that fussy little bird by the windowsill trilled out a love song of blue hepaticas growing on a hillside against a tiny forest of maidenhair blowing in the breeze, dew pearled and lovely with the rising sun upon them.

The morning breeze blew the curtain in at the window, blew sweet breath of flower-laden zephyrs into her face, reviving her, and suddenly she wanted to see that flowery hillside very much and to see if that young stranger was really as interesting as he had seemed the day before. She opened one eye, stole a glance at her clock, and then she was wide awake. She found the little nymph-green knitted dress that fit an early trip to the woods and the soft brown suede tramping shoes, gave a hasty rumpling to the big gold waves of her hair, and was ready.

She thought she heard footsteps coming down the pavement in the stillness of the morning as she crept into the hall and down the stairs, softly not to wake that dreadful brother of hers, and when she opened the front door ever so silently, there was the stranger lingering down by the group of hemlocks beyond the daffodils. He gave her his brilliant smile and a quiet lifting of his hat for welcome and seemed to know they would go quietly and not disturb the sleeping town as they walked through it.

Out beyond sight of her father’s house, Constance drew a breath of relief. Her brother hadn’t wakened. It wouldn’t matter whether anyone else saw her, although it suddenly occurred to her that it was rather odd to be walking off with a stranger at this early hour in the morning.

“This is simply great of you,” said Seagrave, looking down upon her, his eyes full of light. “I’ve been wondering all night if you would come.”

“Why, so have I,” gurgled Constance with a breath of a laugh. “Or no, not wondering,” she corrected herself. “I was very sure I wouldn’t, of course.” She laughed. “You see I really haven’t time. I’m leaving in about three hours.”

“I know,” he said gravely. “I’m sorry.”

“I just couldn’t resist the desire to see where those darling flowers live when they are at home,” she said quickly to hide the commotion she felt in her mind at the serious way he took her going. This really was all wrong, she told herself, but it was fun, and of course it would soon be over.

All too soon they arrived at Hepatica Hill and dropped down to worship the beauty. It seemed to Constance that she had never been in such a beautiful spot before, and she drank her fill of the day and the hour, the sky and the wonderful flowers.

Then they grew silent sitting on the hillside with the blue flowers at their feet and the fringe of fern beside them. Looking off over the valley, the town in the distance, taking deep breaths of fine air, thrilling with the song of a bird in the top of a tall tree, they were filled with the awe of the morning.

Suddenly he turned to her with that grave, sweet smile she had seen first on his face at the church.

“How long have you been saved?” he asked, as simply as if he had asked how long before her college would be over.

Constance looked up in a great wonder and stared at him.

“Saved?” she echoed, and again, “Saved? I … don’t know just what you mean. Saved from what?”

He gave her a startled look, and then a great gentleness came upon his face. As if she had been a little child he explained, simply, “Sunday we united with the church,” he said slowly.

“Yes?” she said with a sharp, startled catch in her voice and giving him a keen look. Had he seen through her playacting? Did he know how loath she had been to parade before the world in that way?

“You united on profession of your faith, not by letter from another church as I did. I was wondering—perhaps I have no right to ask on such a short acquaintance—but I was interested to know if you had been a Christian a long time or had just come to know the Lord?”

He waited in a sweet silence for her answer, and Constance looked up and then down in confusion.