Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

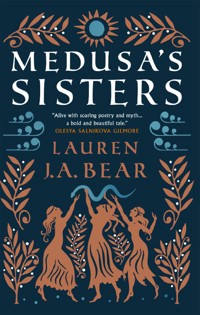

A vividly stunning reimagining of the myth of Medusa and the sisters who loved her, in this captivating, moving debut novel, perfect for fans of Stone Blind and Ariadne. Even before they were transformed into Gorgons, Medusa and her sisters Stheno and Euryale were unique among immortals. Curious about mortals and their lives, Medusa and her sisters entered the human world in search of a place to belong, yet quickly found themselves at the perilous center of a dangerous Olympian rivalry and learned – too late – that a god's love is a violent one. Forgotten by history and diminished by poets, the other two Gorgons have never been more than horrifying hags, damned and doomed. But they were sisters first, and their journey from seaborne origins to the outskirts of the Pantheon is a journey that rests, hidden, underneath their scales. Monsters, but not monstrous, Stheno and Euryale will step into the light for the first time to tell the story of how all three sisters lived and were changed by each other, as they struggle against the inherent conflict between sisterhood and individuality, myth and truth, vengeance and peace.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Cast of Characters

Prologue: Enter Stheno, Alone

First Episode Stheno

Second Episode Euryale

Third Episode Stheno

Fourth Episode Euryale

Fifth Episode Stheno

Sixth Episode Euryale

Seventh Episode Stheno

Eighth Episode Euryale

Ninth Episode Stheno

The Child

Tenth Episode Euryale

Eleventh Episode Stheno

Twelfth Episode Euryale

Thirteenth Episode Stheno

Fourteenth Episode Euryale

Fifteenth Episode Stheno

Sixteenth Episode Euryale

Seventeenth Episode Stheno

Eighteenth Episode Euryale

The Challenge

Nineteenth Episode Euryale

Twentieth Episode Stheno

Twenty-First Episode Euryale

Twenty-Second Episode Stheno

Twenty-Third Episode Euryale

Twenty-Fourth Episode Stheno

Twenty-Fifth Episode Euryale

Stasimon Enter Chorus

The Fool

Twenty-Sixth Episode Stheno

Twenty-Seventh Episode Euryale

Twenty-Eighth Episode Stheno

The Hero

Twenty-Ninth Episode Euryale

Thirtieth Episode Stheno

Thirty-First Episode Euryale

Thirty-Second Episode Stheno

Thirty-Third Episode Euryale

Thirty-Fourth Episode Stheno

Thirty-Fifth Episode Euryale

Thirty-Sixth Episode Stheno

Thirty-Seventh Episode Euryale

Thirty-Eighth Episode Stheno

Exodos Enter Stheno, Alone

Author’s Note

List of Primary Sources

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Medusa’s two almost-forgotten sisters—Stheno and Euryale—come to enchanting life, telling their own stories, bound to Medusa yet separate and fiercely free to make their own destiny. Medusa’s Sisters gives us an intimate look at what it means to be an immortal yet walk and live among human beings. Lyrical, exquisitely detailed, and poignant.”

Margaret George, New York Times bestselling author of Helen of Troy

“With stunningly beautiful prose, Lauren J.A. Bear has deftly tugged on myths of old to weave a fresh and feminist modern legend from the dusty references of Medusa’s once-forgotten sisters. Perfect for fans of Circe, this is easily one of the best books I’ve read this year. Prepare to be enthralled!”

Stephanie Marie Thornton, USA Today bestselling author of Her Lost Words

“Medusa’s Sisters is a wonderful, powerful story that totally absorbed me. Clothed in Greek mythology, it explores the loyalties and conflicts of family – especially the relationship between sisters who are bound together at birth but also need the independence to claim a life of their own. It is a compliment to Ms. Bear’s writing that I never saw monsters, only sisters.”

Anne Bishop, New York Times bestselling author of The Queen’s Price and Crowbones

“Medusa’s Sisters is a stunning debut. Lauren J.A. Bear writes with lyrical elegance, her gorgeous prose illuminating the fierce power of women, the bonds of sisterhood, and the enduring strength of myths and legends. A gloriously feminist novel that achieves both historical richness and modern relevance. As thought-provoking as it is entertaining. I couldn’t put it down.”

Mimi Matthews, USA Today bestselling author of The Siren of Sussex

“In giving a voice to those long silenced, Medusa’s Sisters brings the cosmology of ancient Greece to vivid life, writhing and seething with numinous possibility. It is a story of monsters and mortals, and the gods who use them both with careless cruelty.”

Jacqueline Carey, New York Times bestselling author of Kushiel’s Dart and Cassiel’s Servant

“Bold, beautiful, and brilliantly subversive, Bear’s incredible debut is engrossing from the very first page. With her ambitious storytelling, Bear breathes life to characters often reduced to the shadows, and has proven herself as a talent to watch!”

Claire M. Andrews, author of the Daughter of Sparta trilogy

“Lyrical, brilliant, and deeply moving, Medusa’s Sisters connects the stars—the myths you thought you knew—in startling new ways. Prepare to be devastated.”

Mary McMyne, author of The Book of Gothel

“Alive with soaring poetry and myth, Medusa’s Sisters sparkles as a delightfully feminist subversion of the maligned and forgotten Gorgon women, reframing and bringing their shadowy legend fiercely, vengefully, into the light. A bold and beautiful tale about sisterhood, motherhood, and what it truly means to be a woman.”

Olesya Salnikova Gilmore, author of The Witch and the Tsar

“A must-read for Greek mythology fans seeking new depth in their tales and those who enjoyed Madeline Miller’s Circe or Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls.”

Library Journal (starred review)

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Medusa’s Sisters

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364728

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364735

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2023 Lauren J. A. Bear. All Rights Reserved. Published by arrangement with the Ace, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Lauren J. A. Bear asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For my mother,For my father,For my brother:the three strands of my braid

It is immediately obvious that the Gorgons are not really three but one + two. The two unslain sisters are mere appendages due to custom; the real Gorgon is Medusa.

—JANE ELLEN HARRISONProlegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1908)

CAST OF CHARACTERS

AMONG GODS AND MONSTERS

GAEA—primordial goddess of the earth

URANUS—primordial god of the sky

PONTUS—primordial god of the sea

CRONUS—supreme ruler of the Titans; god of time

RHEA—wife and sister of Cronus; goddess of fertility and mother of the gods

PROMETHEUS—god of forethought

EPIMETHEUS—god of afterthought

HELIOS—god of the sun

SELENE—goddess of the moon

METIS—goddess of good counsel

LETO—goddess of motherhood

PHORCYS—god of the sea’s hidden dangers

CETO—wife and sister of Phorcys; goddess of sea monsters

THE GRAEAE (DEINO, ENYO, AND PEMPHREDO)—daughters of Phorcys and Ceto

THE GORGONS (STHENO, EURYALE, AND MEDUSA)—daughters of Phorcys and Ceto

LADON—son of Phorcys and Ceto; a dragon

ECHIDNA—daughter of Phorcys and Ceto; a sea dragon, mother of monsters

TYPHON—a monstrous giant; consort of Echidna

OFFSPRING OF ECHIDNA AND TYPHON—the Sphinx, the Chimera, the Hydra, and Cerberus

DORIS—a minor sea goddess; mother of the Nereids

AMPHITRITE—wife of Poseidon; a Nereid

PANDORA—a human; wife of Epimetheus

ZEUS—supreme ruler of the Olympians; lord of the sky

POSEIDON—brother of Zeus; god of the sea

HADES—brother of Zeus; ruler of the Underworld

HERA—wife and sister of Zeus; protector of childbirth and marriage

HESTIA—sister of Zeus; goddess of the hearth

APHRODITE—goddess of love and beauty

ATHENA—daughter of Zeus; goddess of the city

APOLLO—son of Zeus and Leto; Artemis’s twin; god of light and music

ARTEMIS—daughter of Zeus and Leto; Apollo’s twin; goddess of wild things

HERMES—son of Zeus; messenger of the gods

ARES—son of Zeus and Hera; god of war

HEPHAESTUS—son of Hera; god of the fire and forge

DIONYSUS—son of Zeus; god of wine

IN THEBES

CADMUS—king of Athens

HARMONIA—his wife; daughter of Ares and Aphrodite

INO, AGAVE, AUTONOË, AND SEMELE—daughters of Cadmus and Harmonia; princesses of Thebes

POLYDORUS—son of Cadmus and Harmonia; prince of Thebes

DESMA—Semele’s nurse

HASINA AND ANNIPE—Semele’s servants

IN ATHENS

ERASTUS—a musician

LIGEIA—wife of Erastus

THALES—nephew of Erastus and Ligeia; an athlete

FRIXOULA—a high priestess

CHARMION—a madam

MENODORA—a hostess

HAGNE AND ASPASIA—Charmion’s employees

BETWEEN THE ISLANDS

ACRISIUS—king of Argos

DANAË—daughter of Acrisius

PERSEUS—son of Danaë

POLYDECTES—king of Seriphos

DICTYS—brother of Polydectes; a fisherman

ORION—a hunter

OENOPION—king of Chios

MEROPE—daughter of Oenopion

PROLOGUE

ENTER STHENO, ALONE

With or without a name,for beings such as me,I must begin.

—Anonymous, “Anonymous”

IHATE THE NUMBER three.

It is an unholy character—complicated, messy, confrontational. Small and odd and prime.

It was my identity, and then it wasn’t. Now I’m haunted by its prevalence.

Mathematicians may argue, three is beautiful! Take the perfection of an equilateral triangle, for instance. Or solving proportions with the rule of three. There exists a theory of triangulation that within the unique power of triangles, truth is always revealed.

Ha!

Scientists slobber like ravenous dogs over three: the states of matter, the dimensions of space. Solid, liquid, gas. Land, sky, water. Sun, moon, and stars.

Three is human life: mind, body, and soul. It is ritual. Morning, noon, and night. Three meals a day. Three trimesters of pregnancy. It is also dramatic. Aristotle’s three unities. Aeschylus’s trilogy. Beginning, middle, and end. Past, present, future.

Within my own world, threes appear with cruel frequency. Beasts with tri-forked tongues or triple heads. Cronus and Rhea had three sons and three daughters. The oracle at Delphi’s tripod. All us “weird” sisters—the three Fates and Furies, three Graces, three Harpies. Or the nine Muses, multiples of three. The triple goddess, Hecate—maid, mother, and crone—whom we would witness transform throughout cultures, beneath hegemonies, across time and place.

Poseidon’s trident.

The three maiden goddesses.

The geometry of hearts, minds, and souls, however, obeys no law of balance. There is no perfect trinity, for three connotes competition. Power struggles. Favoritism and loneliness.

We were almost not a trio; although now that she is gone, neither of us feels like a duo. We are not twins, nor will we ever be. Our third was the center, and when we lost her, we also failed each other, collapsing inward upon ourselves.

A broken triplet. Thrice blessed. Thrice cursed.

Our tragedy is a famous one, devoured and regurgitated. Sensationalized, of course. Misrepresented. A trio of malevolents! And the youngest? Well, that depends upon whom you ask. A symbol of wrath and rage, but also sex and desire. Every time her drama repeats erroneously, she dies again. And our stories—our survival—become even further removed from the annals of history.

We have lived long enough to watch heroes become monsters. We oversaw the emergence of gods and welcomed their disappearance. Kingdoms raised, then set to flames. Endlessly. Over and over again. Different casts and settings, same plot.

Life adapts; it evolves. Yet betrayal—in word and deed, by lover and kin—remains remarkably the same.

Perfidy by jealousy and by love.

For we are women, still, despite what we were made.

To be ageless and anonymous, immortal and ignominious.

Famous and feared, yet nameless.

We know you have never heard of us, but that is no bother. We stopped caring a long, long time ago. Back on those rocks, that beach, surrounded by the waves that crashed unceremoniously at the rite of her immortality. When our sister finally achieved what she was denied at our birth and became a legend.

Our mortal sister is dead.

She was Medusa.

And we are the Gorgons.

* * *

AFTER HE TOOK Medusa’s head, Perseus threw up.

His bile coated the boulders that were our home; green and yellow chunks of cheese and herb slid viscously into the sea. The resounding splatter both a grotesque knell and a final desecration to our refuge, the altar of our family.

Perhaps the newness of flight upset his stomach—it’s not an easy sensation for anyone, let alone an unpracticed boy. But this day has been consigned to the poets, not the witnesses, and those lofty minds would never allow their Chosen One any deficiency. It was her gut-wrenching reflection in his gods-given shield! Blame the hag, men! I can almost hear the smug chortles.

I was there, though, and must differ. The act itself made Perseus sick. It was compunction, the very wrongness of what he did.

Perseus slaughtered a sleeping woman. An unarmed, innocuous stranger to him and his people.

There was no fight—aren’t warriors forged in battle?

She didn’t even scream.

And she was pregnant.

Yes, Medusa was pregnant and asleep, but Perseus became a hero. For she was only a beast, scaled and feathered, a body for Perseus to define himself upon.

Nobody requested our testimony. The voices of ugly women are easily diminished. Perseus could pretend that Medusa charged, threatened to tear open his chest with her claws and suck the life from his still-beating heart. Nobody challenged his account. He was so human, so young and beautiful, and we were . . . deformed.

Make no mistake, truth and goodness are merely aesthetics. I wish I had known this when I was still pretty.

I have had lifetimes to reflect, and if I ever had a chance of killing him, it was that moment, as he wiped away the runny mess of tears and snot with the back of his hand. But unlike Perseus, I beheld my nemesis in his weakness and, though an inchoate darkness coursed through my veins, I hesitated.

He was no more than a child, younger even than Thales—Oh, Thales. I’m still so sorry—and mucus clung to his beardless chin. Strange how I stared at that putrid discharge, how it consumed my focus, when my youngest sister’s head dangled from his left hand.

I could not meet her eyes and he—of course—would not meet mine.

A disconnected triangle.

If only . . .

But then Euryale broke through my trance with cries bereft and feral: “Stheno, the babies!”

And so I did not sink my fangs into Perseus’s adolescent neck and shred his throat, spilling his life into the blood he took, blending hero and villain for eternity. My remaining sister’s words confounded and overthrew me. Fettered me to a reality I no longer recognized but vaguely recalled.

The baby? No, babies.

And so I faltered, and my enemy remembered to flee.

Perseus grabbed his inherited gifts, and his savage trophy, and escaped into the fog. Disappearing into his name.

Dispel everything the poets—who never met her—penned. Medusa rarely angered. She was ebullient, the paradigm of magnanimity. Liquid sunrise poured into her soul, and she woke each morning full of hope. Even after all her suffering, if she were given the opportunity, I do not think she would have fought back.

I am the vengeful sister. Me, Stheno. The hateful pariah who murdered more men than either of the other two Gorgons combined.

I consider this no accomplishment. I do not gloat, but neither will I atone. I am descended from a brood of sea creatures that humans deem beasts, and isn’t that what monsters do? We maim and torture and feast upon the gore. We delight in destruction, drinking our victims’ blood from golden chalices and dancing circles to their pleas.

But on that day, the one that mattered most, I paused.

I could have effortlessly killed Perseus—the ancestor of Heracles—and forever changed the mythical record of our age, but instead I chose my sisters.

FIRST EPISODE

STHENO

The way of sisters is more arcaneeventhan the ways of gods.

—Erastus of Athens, “The Theater of Sisterhood”

FIRST YOU MUST accept that monsters have families.

My mother and father, two ancient sea deities of notorious danger, gave me eight siblings, but we were not raised together. Couldn’t be, for we were separated by more than birth order—by our physical shape, our otherworldliness. Human families, by comparison, are so simple. Maybe one child has brown hair, the other blond. Eye color may range over shades of blue. Oh, how mortal parents dramatize these trite differences! Discussing in laborious detail how one learned to walk a whole month before another! Inconceivable!

In my family, some of us had tails.

Deino, Enyo, Pemphredo, Echidna, Ladon, and I share parents, but Medusa and Euryale are my sisters. Just as the Graeae were born together, so were we Gorgons.

We would not be called the Gorgons, however, for many, many years.

My grandparents were primordial beings, the sea and earth themselves, present at the creation of the world. This union between Gaea and her second husband—her own son Pontus—produced my parents. My father, Phorcys, married his sister and female counterpart, Ceto, and all their progeny came to life during the Golden Age of the Titans, well before Zeus was hidden in a mountain cave on Crete and Cronus swallowed the changeling rock.

Yes, I watched Zeus release the monsters of Tartarus and conclude the ten-year campaign against his father, victorious. His lightning bolts became the harbinger of a new era, the Silver Age, where he was lord.

Though well hidden from the fray, I also witnessed the Titans meeting their punishments. Prometheus and the eagle. Atlas and the world. I should have paid closer attention when these so-called Olympians, denizens of the highest mountain, attacked those who wronged them with dogged maliciousness. Maybe then I would have been more prepared for how they treated the rest of us.

On days when I’m especially cynical, I find it almost laughable that I am older than both Poseidon and Athena, who would wreak such havoc upon my life. No respect for elders in the immortal community, I’m afraid. But then again, so much of age is attitude, and it took me far too long to acquire one.

I sound just like my mother. That happens to immortals, too, when we become old.

And I’m getting ahead of myself. I do that sometimes. Time holds little consequence when you occupy forever.

The story of our birth, then.

My mother, Ceto, resided in a watery cave beneath Mount Olympus, connected to her precious seas through endless tunnels and labyrinthine streams. Though my father adored his wife, he did not attend her labor—a messy, menial process, which he considered a female’s work. And for reasons inexplicable—both then and now—matters of the womb are unpalatable to masculinity.

I have viewed battlefields covered in unspeakable gore, but I have seen delivery beds far, far worse.

I am extremely old.

At my mother’s side stood her first set of triplets, the Graeae, or gray women. Another trio forced to sacrifice their individual identities for group nomenclature. Born with gray hair and skin, Deino, Enyo, and Pemphredo shared one detachable eye and tooth. I never found them ugly, despite that deficiency. Their gray faces were more interesting than unpleasant, and unlike my sisters and me, the Graeae had a gift: the modest ability for prophesy, to guide those who wander or are lost.

Though if they ever deigned to advise us in those early days, we certainly didn’t listen.

When Ceto’s contractions commenced, my mother summoned Doris, the wife of her other brother, Nereus, for Doris bore the nearly fifty Nereids and thus had plenty of experience with labor.

Still, complications arose.

I emerged first, en caul—within the protective sac indicative of my immortality. My aunt ruptured the bubble and released me, red-faced and stoic, upon the world. Doris smacked my bottom with her aquamarine hand to summon tears, but I refused to cry. I frowned at her repeated efforts, bringing Ceto great felicity.

“This one will be unforgiving!” she laughed between bites, for our mother ate the caul of all her immortal children. With jelly dripping from the corners of her mouth, Ceto named me Stheno, for she knew, even then, that I would be strong.

Euryale followed moments later, screaming incessantly—even within the bloody veil—demanding attention with her first breath. Another family might have greeted her with the affection she so obviously needed, but our callous community only grimaced.

“Make it stop,” muttered Deino, no doubt wishing she also shared a retractable ear.

Though separated by mere heartbeats, Euryale would always be my younger sister. We had to organize ourselves somehow; all living beings crave hierarchy, and we were no exception.

“How do they look?” our mother asked, straining to see her new daughters as her older ones performed the rites of delivery, washing and swaddling.

“Ordinary,” answered Pemphredo on a sigh.

“Fins? Fangs?”

“None.”

“Talons?” wondered Ceto, riding a hope.

“Not even a sharp nail. Ten fingers, ten toes. Two eyes.”

Ceto snorted, then winced as she clutched her lower abdomen. “Doris! I feel another!”

This last baby, however, refused to drop.

“It is breech, I think,” worried Doris, removing red hands from my mother’s birth canal and pushing green hair out of her eyes with a forearm. “I felt a foot.”

“Then go in and grab it!” hissed Mother, gnashing her razor-sharp teeth. Ceto wasn’t only the goddess of the largest sea creatures, but also the most lethal ones. “The little demon is destroying me!”

Poor Doris shoved an entire arm’s length into my mother’s belly, grabbed the baby’s leg, and yanked. When Doris would later recount the story, she claimed the din of my mother’s shrieks blurred the boundary between life and death.

The babe, however, arrived in this world the same way she would leave it.

Voiceless.

She was small and bluish with a shock of dark hair and no caul. A serpentine umbilical cord coiled lethally about her head and neck.

A being born in conflict with itself, choked by its own lifeline.

“Dead,” murmured Doris, with greater surprise than sadness. For my kind, death is more a novelty than an emotional experience. Most of us lack the requisite empathy. Soft hearts aren’t meant to last forever; it is why immortals grow selfish and cold.

Yet Doris was softer than most, and she held the lifeless babe gently while untangling the cord.

“What a shame,” she lamented. “Three would have been a nice number.”

Pemphredo, commanding the communal eye, ran a hard look over the cradled corpse, crown to toe, and her lips tightened. She snatched the tiny baby from Doris’s arms and tossed it into the abyss. Doris yelped.

“Daughter!” upbraided our mother, slamming fists against the miry stones of her cavern. “I would have liked to see it before you fed my beasts!”

Pemphredo shrugged, for she was not inclined to apology. There had been an ominous aura to my youngest sister, and Pemphredo felt only respite to be rid of the pernicious little presence. Besides, our kind did not romanticize babies. You had to be strong to survive in such a world, and this one was clearly weak.

“You really are vicious,” remarked Ceto with some admiration, exonerating Pemphredo’s transgression. “Show me the other two, at least.”

Deino and Enyo brought Euryale and me into the moonbeams that descended from the cave’s natural skylights, casting our neonatal features in an opaline glow.

“They are common.”

A failure.

Later, we would be called “human form.” No physical deformities, no aberrations of color. We were my parents’ most conventionally beautiful offspring—cherubic, even—and, thus, their least impressive.

“They are lovely,” corrected Doris, overcompensating. “And their eyes are so unusual!”

“Indeed,” Ceto responded sadly, inspecting the four miniscule orbs staring up at her expectantly. Mine were red ocher and Euryale’s shone amber. Our mother gave them half a breath of consideration—and tried to find some satisfaction—when the tunnels began to shake, rattling loose stones and dirt from the walls. “Stitch me up, Doris, my husband comes!”

Our brief chance at being special come and gone.

Pemphredo threw the remains of afterbirth to my mother’s white-bellied shark, who lingered in a nearby pool, while Doris rinsed and tidied my mother’s lower half. Ceto, already beginning to heal, prepared herself for the arrival of my father in his seal-led chariot.

“Bring them to me!” she ordered, flapping her arms impatiently.

Deino and Enyo dutifully—blindly—passed us to our mother, who quickly assembled a maternal tableau: a babe propped in the bend of each scaly arm, her own head tilted downward in a vain attempt at demure. However, to Ceto’s disappointment, it wasn’t Phorcys emerging from the quaking subterranean depths, but rather, my other sister, the she-dragon Echidna.

Half speckled serpent, half maiden, Echidna was—at that time—my parents’ most prolific issue. She resided in the fetid, slimy waters of the most arcane depths below the earth. With her monstrous storm-giant consort, Typhon, Echidna birthed some of the most profligate abominations on land or sea: the Hydra, Cerberus, the Chimera, and the Sphinx.

Ceto respected nobody, but Echidna at least commanded my mother’s attention.

And at that moment, Echidna made quite the entrance, heaving with anger, the disposed baby pressed tightly against her chest.

“Who did this?” Echidna demanded, seething, her black eyes darting between Doris, Ceto, and the Graeae.

“I did,” responded Pemphredo, insouciant as always. I would later nickname her the Wasp, for she seemed both free of fear and full of sting.

“We did,” corrected the other two Graeae, in unison, for it was innately understood—even then—that our family’s triplets elicited collective punishment.

“I understand your vision is limited, gray sisters, but your one eye fails you. This infant lives and breathes.”

Our mother gasped—I imagine with some amusement. “Pemphredo, you wretch! Hand her to me, Echidna! Now.”

Of course, I hold no natural memory of this day, but each time Doris recounted it later, she would pause at this part—linger on the lone heartfelt moment—for Echidna did not want to release the baby. Connections form quickly in my world. Love can be found at first sight and enmity even earlier. The bond between Echidna and my youngest sister was adamantine, instantaneous. Only reluctantly, and with much haggling, did she surrender the child to her rightful mother.

Many times, I have wondered how the trajectory of our lives might have curved if Echidna refused—even if she kept only the one of us. Are we so attached to our fates? To our catastrophes?

Echidna, after all, would suffer so much more than she deserved.

My mother blew her salty breath into the little face, and the baby’s eyelids parted, revealing eyes as green as peridot.

“She is different, somehow,” Ceto noted, comparing the salvaged babe to my other sister and me. “This one is changed, in a way I can’t describe.”

“She is mortal,” Echidna claimed. “Her immortality was stillborn.”

“Unusual,” murmured Ceto.

“But possible,” added Deino, yielding the wisdom of the eye. “She was not en caul. She will die.”

“Of old age. Or sickness,” elaborated Enyo.

“Or murder,” finished Pemphredo.

“You see her future?”

“Not clearly,” Deino replied. “We cannot tell how she will leave this world.”

“Or when.”

“But she will leave it? You are certain?”

Pemphredo nodded. “Kill the baby now. It will be a mercy.” It was an argument born of the most abject pragmatism, and echoed by the other Graeae.

“What can a life mean for one who will die among those who cannot?” wondered Enyo.

“This babe will always be at risk,” reasoned Deino. “It will be unfair to the other two sisters, futile, like yoking them to a broken plow.”

Ceto deliberated. She operated within her two natures, made manifest in the twin leviathans flanking her at all times. Sometimes she was a whale, tribal and sage. At other times she was a lone shark. Bite first before you are eaten.

“Your daughter lives,” contended Echidna. “Infanticide, especially within a family, is an act of great darkness. An anathema, even among our kind.”

Ceto pursed her lips. “And what does Nereus’s wife think? Do you side with my gray children or my sea dragon?”

Doris shook her head, wisely abstaining from the family’s division. “All your children offer cogent counsel, but you are the mother. It is your choice.”

Echidna, intrepid and fervent, locked eyes with Ceto. “As such, you will bear the punishment.”

It must have been quite a sight: two monsters, mother and child, engaged in a war of wills.

“If you do not make your claim,” finished Echidna, “I will keep her.”

And it was this statement that spared my sister from becoming chum. I suspect my mother made the decision mostly out of intrigue: What was it about this divisive baby that inspired Echidna’s advocacy, her attachment?

“I will acknowledge this mortal, who is somehow a product of me and my brother-husband.” Ceto laid us babies upon a bed of woven seaweed, and we squirmed into our familiar positions. Reunited by touch and feel. “Whether she be an honor or a curse, let none of you harm her.” And Ceto flicked her wrist, decree delivered.

Echidna lowered her head, as pleased as the Graeae were jealous and Doris was eager to leave.

“What will you call them?”

“Stheno,” Ceto began, like the opening of an invocation, as she touched our brows. “Euryale.”

And she paused, lingering on the third infant—the babe who almost wasn’t. Ceto bared her teeth. “And the little queen.”

Pemphredo scoffed.

Then Ceto whispered the name that would become lore when it was still only a name, nothing more.

“Medusa.”

* * *

I HAVE HEARD mortals express a similar sentiment, but it felt like we were children for only a few precious, ephemeral moments. One day we were waddling about caves, the next toddling into streams. Unclothed and unkempt, we splashed and submerged, venturing farther from home. We dove headfirst into the sea and, though we lacked any unique, discernible magic, we swam with the prowess of our bloodlines to the farthest reaches of life.

We bored Ceto and Phorcys, who cherished their gruesome pets and their lust for each other with far greater energy than they ever exhibited toward their children. For a time, Ceto sent warm-blooded sea creatures to nurse us: whales and seals, sea lions and dolphins. But after a while, she forgot.

And once she birthed our only brother, Ladon, we were truly left to fend for ourselves, for who could compete with a full-fledged—male—dragon?

On rare occasions, Phorcys would take us three for an undersea ride to a grotto off the coast of Ithaca, his haven long before the island found consequence. He did not know how to be a parent, and did not consider us part of his domain, but I accepted his failings just as I could not forgive Ceto’s. Unfair, I know, but so are most preferences. Our father, gray-haired like the Graeae and fishtailed like his sister-wife, had spiky crab skin and claw forelegs shooting from his body—neither of which fostered warm hugs. Still, by the light of his torch, Phorcys delivered his best—and only—paternal advice:

“Stay together.”

Did he speak directly to me, or have I reimagined it so? Regardless, I more than listened; I drank his words. Ingested them. Branded that two-word command upon my heart, my spirit, my purpose, and my existence.

Stay together.

“We will, Father. I will.”

And truly, we did not need parents when we had one another. Our shared commonness became our serendipity, enabling an unfettered independence. I can think fondly of our idyllic childhood, not just because we were a whole trio, but because we were free. Of all our relations, my sisters and I were the least restricted—no offspring to nurture or prohibitive physical size. We weren’t fearsome or mighty, intimidating, or execrable. We were beautiful, of course, but unnoticeable, which provided us a false security: we assumed we could forever escape notice and dodge trouble.

We were wrong, of course. Both would find us, but not before we explored the limits of fantasy.

My sisters and I visited Ladon, who guarded the far western garden islands, via the conduits of Oceanus. There, the Hesperides tended to a grove of golden apples, and long before those fruits touched the hands of Atalanta or Eris, we caught our reflections in their amber shine. We giggled and whispered beneath the arbors, in and out of shade, as Helios led his radiant chariot across the sky and our shadows danced.

“Do you think trees communicate with each other?” wondered a child Medusa.

Euryale scoffed.

“See how these trees lean, how they grow toward each other! And then look at those far ahead.” Medusa gestured to an apple tree infected with rot, its trunk cankered and black. “The healthy tree beside it bends. I think it mourns. I think trees feel pain.”

“This conversation is painful,” muttered Euryale, closing her eyes.

I ignored her. “If that is so, Medusa, do I hurt the fruit I eat? Should I apologize to the blade of grass I bend, the flower I pick?”

“No. But perhaps we could be more grateful.” Medusa brought a discarded apple core to her eye level. “Thank you. You were magnificent.”

I smiled, Euryale snorted, and when the Sunset Maidens commenced their pleasant melodies, we leaned together, like drowsy trees.

“It is peaceful in this part of the world,” Medusa murmured, laying a head against my shoulder.

“Tedious,” Euryale corrected.

“Serene.”

“Droll.”

“The only monotony is your bickering,” I moaned, lying back between them, physically and figuratively.

As always.

Euryale poked a sharp fingernail between my ribs. “Maybe the trees bicker, too,” she rejoined, mocking us.

As always.

Sweet Ladon, who licked honey from our fingers and performed tricks for cakes, sensed tension and padded over, curling his long, emerald-colored tail around our three naked bodies. We had no need for clothes then, half-feral as we were.

I stroked his scales and he purred like a cat.

Before the sun set on the edge of the world and Medusa fell asleep, she cuddled against me and sighed. “If things get bad, we could come back here. Or maybe we should stay.”

For it was a chaotic time. When we were still so very small, Echidna’s savage and stormy husband rose against Zeus. Even to a child of monsters, he terrified. Typhon was larger than any giant, and though he had a man’s torso, he had no legs. Instead, he slithered upon two massive vipers’ tails. An enormous pair of wings rose from his muscled back, as well as other animal heads—some that spit poison. He had long, wild hair, a matted beard, and eyes that flashed red with fire. My most prominent memory of my sister’s grisly husband is a visceral one: It is a strident sound that ground my teeth and rattled my bones. Typhon moved with the noise of a barbarous horde, a roar so cacophonous I would cower and cover my ears at his approach. His voice alone caused the earth to shake.

But he was Echidna’s lover and he treated her with tenderness. She devoted herself to the children of their union. That’s monsters for you.

Typhon despised Zeus, whom he deemed a pathetic replacement for Uranus and Cronus. He believed only one such as himself—a father of monsters—deserved sovereignty among the immortals, and thus, Typhon rebelled against the heavens, only to fall by Zeus’s lightning bolt. Stunned but not slain, Typhon’s mighty hulk was dragged across lands and imprisoned under the mountain called Etna. Once he roused and discovered his entrapment, Typhon continued to rage and revolt, punching holes through the ground and spitting fire to the surface. His behavior prompted Hades to ride from Tartarus in his black chariot, to ensure the border between the living and the Underworld remained secure.

(And if not for this unruly captive, Hades might never have stumbled upon Persephone, gathering daffodils in a nearby meadow. But that’s how stories are cultivated. Words and actions are sown, spreading repercussions like wildflowers: monsters begetting lovers begetting conflict begetting heroes. On and on, endlessly.)

After Typhon’s castigation, Echidna’s embattled heart buckled. And while a more unlikely pair couldn’t be imagined, little Medusa spent days and nights in the sea dragon’s caliginous lair, mourning by her side, holding Echidna’s hand and rubbing her back while she wept, singing in her charming but off-key way. I’m not sure Echidna would have survived this period without Medusa.

It was a life debt repaid.

Though Echidna performed no active role in Typhon’s attempted coup, our sister adamantly refused to denounce her husband. To do so would abnegate all her principles, convictions that surpassed reason or self-preservation. Still, Zeus spared her from any punishment. At the time, I considered his clemency a peace offering to the old gods, but generations later the god of the sky’s intentions became clear. He needed Echidna because he needed her children. They would all play a part in his plans for the age of man.

Yes, the age of man. Humanity. Zeus’s esoteric experiments with creating humans fascinated my sisters and me, and we gleefully observed them go wrong time and again.

We watched atop boulders in the sea when the first humans—all male, in their maker’s image—died out within a generation. And while we lolled beside the rivers, feet splashing against the stream, we witnessed Zeus annihilate the second race of men, the ungrateful ones who refused to properly pay homage. We climbed to the tops of the very same ash trees that formed the warlike third race after they inevitably killed each other off.

“This is all so stupid,” argued Euryale. “Why does Zeus invest so much time and energy into something that always fails?”

I felt inclined to agree, but Medusa remained steadfast in her support.

“Humans are fascinating!” she insisted. “It’s nearly impossible to predict what they will do next.”

Euryale rolled her eyes. “I know what happens next, they die.”

I shot my middle sister a furious look, and she had the decency to blush. The mention of death always altered the mood, for we could never forget that Medusa was mortal. Though her life span was indefinite—a benefit of her ancestry—she lived within consistent limitations and at constant risk. She bled and she bruised. She hungered and needed rest. After hours in the sun, her skin browned and hair lightened.

When she climbed too high, I worried. Same as when she wandered too far or swam too long. Would that mushroom kill her? That whirlpool? That fall?

Medusa’s preoccupation with humans, I always believed, was a fascination with their corporeality. She watched them because she needed to see how beings aware of their imminent death chose to live.

In an immortal community, time holds no obvious value, but when time doesn’t matter, neither do a lot of things. And Medusa, whose days were limited, desired a structure our aimless wanderings couldn’t provide.

Because her life would end, it needed to matter.

As I have already admitted, in our earliest ages, I struggle to remember chronology without glaring anachronisms. However, I do know—without equivocation—that everything changed when Zeus delegated his mortal project to the Titan brothers, clever Prometheus and scatterbrained Epimetheus. Their success with both humans and animals, after all Zeus’s failure, forced life into a structure of time, and it altered Medusa. She longed for entities I didn’t consider essential: excitement and experience, a richness to her finite existence. A definition.

For as mortality became synonymous with human, what did that make Medusa?

Physically, Medusa matured at the same rate as Euryale and I—that is to say, very slowly. It took many, many years for our bodies to finally shed childhood, and then, just at the verge of womanhood, we paused.

We seemed to be stuck, waiting, but for what or whom I did not know.

SECOND EPISODE

EURYALE

She lifts her dress to wade,this river girl.She bares her anklesand shows her heart.

—Erastus of Athens, “The Illness of Maidens”

WHILE MEDUSA PERSEVERATED on those anemic humans, Euryale pursued a far nobler race.

The Olympians overshadowed humans and outshone the Titans. Their powers were vast and vigorous, their bodies beautiful. They behaved in ways that celebrated decadence and ambition, and the passions and feuds of their personal lives thrilled Euryale. Hungry for snippets of their hierarchical melodramas, she consumed the gossip and obsessed over their increasingly tangled relations.

Beside such sophistication, Euryale’s own family seemed crude. On childish adventures with her sisters, while they played in tide pools and built landscapes of sand, Euryale daydreamed about making a home on Mount Olympus. She smiled, imagining Ceto’s shock and envy when her benthic-born daughter ascended to the clouds. Euryale’s sisters would be invited to visit, but never to stay, for her husband and children would require too much of her attention. After she hosted Stheno and Medusa with divine treats and regaled them with stories of her marital bliss, she would send them on their way—with a fine gift, naturally, for such riches would be nothing to her.

Dry your eyes, sweet sisters, I will find time for you again, soon.

But it would be humankind, ironically enough, who served as the catalyst for Euryale climbing that famed mount.

When Prometheus broke Zeus’s trust by gifting humanity with fire, he upset the balance of power. After the Titan’s brutal sentencing, Zeus was forced to make peace with the culprit’s brother, for he didn’t need another embittered god seeking vengeance. Zeus commanded Hephaestus to form a human woman from clay as Epimetheus’s consolation prize. Though no lovelier than any immortal, this human woman was blessed. One by one, the Olympians honored the dirt-born imposter with a present that outdid the last. Music from Apollo. Majesty from Hera. A sapphire-studded silver gown woven by Athena’s own hands. Hermes gave her a name. Pandora.

And, of course, Zeus bequeathed a sealed vase.

It made Euryale’s blood boil. What an infuriating waste.

In a spirit of unity, Zeus invited the entire pantheon to the wedding he hosted within his palace on Olympus. Euryale and her sisters, as children of the old order, were included, and as they entered the royal complex, Euryale missed no detail of her environs: the heavy fortifications of purest marble and hardest bronze, the golden gates and shimmering pavement. She had never seen so many buildings in one place, stables and chambers and halls—more rooms than she could count. Even the air was immaculate, an ether of luxury, the breezy confidence begotten of worship.

And above it all arched a rainbow. This was perfection.

The sisters watched from the farthest outskirts of the cloistered courtyard as Epimetheus and Pandora beheld each other for the first time. The bride wore an aureate crown, threaded with garlands, and an embroidered veil of spider silk hung suggestively across her face.

“She is more beautiful than I thought possible,” murmured Medusa, eyes bright, awakened somehow.

The groom, aglow with Aphrodite’s desire, gently pulled aside the shimmering cloth to kiss his new wife.

“He is bewitched by her!” furthered Medusa, raising her voice, and even stoic Stheno agreed, nodding along and—Did she just sigh?

This was getting embarrassing.

“She is empty,” Euryale rejoined, correcting her simpering sisters. “Her eyes are as lifeless as two river rocks.”

“You judge too harshly, Euryale. Can you imagine, coming into the world full-grown?” Medusa pushed herself up on the tips of her toes, angling for a better view over the assortment of demigods and beasts delegated to the rear of the audience. “Perhaps she is dumb, or perhaps she is just young.”

“She was born into marriage,” added Stheno, “which would overwhelm any creature.”

“Does she feel and think like a child? Or a woman?”

Euryale’s irritation simmered up through her chest, spilling over the lips of her mouth. “She thinks and feels as much as dirt, Medusa. Because that is all Pandora is.”

“Ah, but dirt goes deep.” Medusa grinned, delighting in the way she could aggravate Euryale. “Does she carry the earth’s memories within her? Does she speak its language?”

“Stheno,” Euryale whispered, “tell your favorite sister to be quiet.”

“You are both my favorite sisters.”

Euryale exhaled through her nose, causing her nostrils to flare. Stheno’s stubborn ambivalence could be more frustrating than Medusa’s endlessly irritating questions.

“Just enjoy the day,” Stheno advised.

“How can I enjoy one of our oldest gods, a Titan, debasing himself with the lowest of life-forms?” Euryale shot back. “It’s sickening.”

Her older sister cringed. “Now you’re the one who should lower her voice.”

“Is it Pandora’s mortality that makes her lesser?” asked Medusa, with no edge, only a patient curiosity.

Yes, Euryale longed to say. Flustered by her private beliefs, she struggled to explain herself. “Epimetheus may love her now, but she will die, and he will live forever. It’s like tying your heart to a butterfly.”

“A short, glorious flight and a sweet landing.” Medusa shrugged. She turned back toward the bride. “A life could be much worse.”

* * *

AFTER THE CEREMONY, Euryale wandered from the gold-paved feasting hall and past the prodigious banquet, accepting a glass of ambrosial nectar on her way. She stopped beneath a covered walkway at the edge of the palace and admired the crisp, panoramic view provided by the mountaintop: viridescent isles cutting through cerulean sea. Clouds like pink rose petals strewn across a forget-me-not sky.

Euryale spent so much time in the water or belowground with her sisters, what a respite to reach such heights!

The world below belonged to the immortals, but for how much longer?

She sipped at her drink and tried to ignore the merriment behind her, where foolhardy Epimetheus allowed himself to be mollified with this human substitute for his brother.

Were siblings so replaceable, after all?

“You are missing quite the party,” came a foreign male voice. “Or is the party missing you?”

His words ran down her body like smooth water, and yet Euryale felt something at the core of her yanked toward him with the strength of a tide. She spun and discovered Poseidon, Lord of the Sea, idling before her, leaning against a column. Hair so dark it shone blue like a mussel’s shell, curled lips, chest bare. She nearly dropped her glass.

“Are you not entertained by Zeus’s beneficence?”

Ignoring the flickering in the depths of her belly, Euryale kept her voice steady, detached. “Entertained, yes, but never impressed.”

Poseidon loosed a low chuckle. “And what of the bride? Her name parts the lips of everyone inside.”

“Not my lips.”

His gaze dropped to her mouth and he stared openly. “I am aware.”

Euryale’s mouth was dry. She swallowed. “How did you honor the bride, Lord Poseidon?”

“With a necklace that prevents its wearer from drowning.”

“Inspired.”

“Not particularly. I forgot then ran out of time.” Poseidon grinned. One of his canines was too sharp and slightly crooked. “She herself is a rather apocryphal present, though, is she not?”

Euryale raised an eyebrow. “‘Apocryphal?’ You doubt Zeus’s intentions?”

“My brother is known for many things. Charity is not one of them.”

“And so all of this”—Euryale gestured to the lavish festivities, the location itself—“is a ruse?”

“I would call it a wily move to restore balance.”

“Between Zeus and the brothers?”

“Between us and them.”

Us.

“Prometheus brought humanity fire,” continued the Olympian. “He is their redeemer. Now Epimetheus will bring them Pandora.”

“And she will be their downfall.”

“You see clearly, Golden Eyes.” Poseidon closed the distance between them as he also took in the view. “And you know my name, but I do not know yours.”

“I am Euryale. Of Ceto and Phorcys.”

His expression shifted from confusion to recognition. “Then you are a grandchild of Pontus. I have heard mention of three beautiful maidens living amid a horde of beasts.”

Beautiful.

“And your sisters?” he asked, scanning the crowds behind them. “They are here?”

She nodded.

“Show me.”

He offered his arm and escorted her back into the clamorous party. Euryale felt the proximity of their bodies like a dizzying blow to the head, and she hoped—she prayed—that everybody noticed their entrance.

“There.” She pointed, forced to raise her voice over the pandemonium. “Tall and somber. My older sister, Stheno.” Poseidon nodded when he located Stheno, standing alone but unbothered at the edge of the crowd, content to observe.

“And the other?”

His face came so close to hers that his beard grazed her cheek, and Euryale struggled to maintain a steady breath. She worried he could feel her erratic pulse.

“Medusa, the baby, is attempting to dance.”

For indeed, Medusa, flustered by heat and humor, attempted to follow a dryad in a complicated dance. She was sweating, laughing, and impossibly bad, spinning the wrong way, crashing into guests, and stepping on toes. Lavender petals flew from the sprigs in her hair.

Euryale winced.

“She has no rhythm,” commented Poseidon dryly.

“She’s an even worse singer.”

Yet the hungry way Poseidon stared at her winsome sister made Euryale frown. Medusa, whose brown hair glinted with gold from long hours in the sun and whose cheeks flushed an annoying shade of dusky rose when pleased, clapped along to the music, just slightly off beat and euphoric.

“She’s mortal,” clarified Euryale quickly. “And odd.”

“Clearly.”

And Poseidon smiled at her, just once, just enough that any lingering worries about her captivating sister vanished from her mind. Poseidon’s hand curved around Euryale’s waist to the small of her back, and he nudged her toward him.

“You’ve shown me your sisters, now why don’t I show you . . .”

But he halted, for Amphitrite approached their periphery. The eldest of Doris’s Nereids—and Poseidon’s wife—resembled the sea-foam at dawn. She wore a stunning, diaphanous gown decorated in pearls and treasures of the sea, and atop her head rested a crab-claw crown and hairnet. Amphitrite did not walk so much as she drifted, as delicate as a water strider on a pond’s surface.

Euryale owned only one colorless, formless shift. No jewels, no sandals. Her hair ran in tangled paths down her back, for she didn’t know how to style it. Standing beside the resplendent ocean nymph, Euryale felt uncouth and exposed; she burned with a new shame.

“My queen.” Poseidon, the adoring husband, bowed.

Euryale inclined her head. “Good evening, Cousin.”

“It’s nice to see you looking so well,” Amphitrite responded. Her words were airy and light but failed to lift her face. Nereids were enchanting, fleet of foot and eager to dance, but this nymph did not rejoice. Amphitrite’s eyes lingered upon her husband’s hand at Euryale’s hip, and she sighed.

“The girl became lost wandering Zeus’s palace, my wife. I have returned her safely.”

“Her sisters must be anxious at her absence.”

“As my brothers whisper and plot during mine. There are no reprieves from the demands of family, even at a party.”

Amphitrite allowed her husband a tight approximation of a smile.

“Give our best to your mother and father, Euryale,” she insisted, a polite signal but a signal all the same.

Euryale understood.

“We will meet again,” Poseidon murmured in Euryale’s ear, secretly stroking the small of her back. “By the sea.”

Long after he ushered his wife back toward their illustrious kin, Euryale felt his voice tickle inside her, felt the absence of his touch.

She knew her cousin’s story well. Poseidon sought modest Amphitrite’s hand, but she fled his advances, hiding below the waves until a dolphin betrayed her hideaway. Poseidon retrieved her, overcame her, and married her.

The order of which differed according to the teller.

The tale made little sense to Euryale then, and now that she had met him? Only a half-wit would resist a union with such an Olympian! Only a prude could prefer chastity to the Lord of the Sea’s bed.

What had he wanted to show her? Euryale shuddered. She would have gone with him willingly—she would not have given chase—and that would have been an irreversible mistake. Amphitrite’s life illuminated one vital message: the value of virginity. As much as Euryale ached for the pleasures of a male touch, she cultivated a nature more calculating than impetuous. No, she would not run from him, for she was no coward. But Euryale would demonstrate forbearance; she would hold her own maidenhood close until it could be used to her best advantage.

When she met Poseidon again, for she knew she would, by the sea, Euryale would be better prepared.

She returned to her sisters, feeling heavier and lighter.

“Where were you?” wondered Stheno.

“What do you mean? I never left.”

“Shall I get us some food?”

And Euryale declined, preferring to savor the deliciousness of her deceit.

* * *

POSEIDON PREDICTED CORRECTLY.

When Pandora broke both her promise and Zeus’s vase, she released ruin upon the mortal world in abundance: disease and death, greed and vanity, slander and envy, toil, old age, and war. Each misery ransacked humanity, forcing Zeus to send massive rains and floods to wash away the mess. Euryale chuckled to herself at Zeus’s plan made manifest.

The rightful balance restored.

She and her sisters oversaw the destruction, perched at a rocky pinnacle like three large seabirds. Far below, humankind floundered in wrathful waters: the symbol of life recast as an instrument of death.

“Poor Epimetheus,” remarked Stheno quietly, hugging her knees to her chest as powerful winds smote the landscape. “Hasn’t he suffered enough?”

Euryale shrugged. “Don’t accept gifts from Zeus.”

“Which one, Pandora or the vase?”

“He should have tossed both into the sea.”

Thunder pealed so loudly it shook rocks loose from the mountainside. The waves rose and raged. Medusa shivered, and the sisters huddled closer together beneath their seagrass blanket.

“Would you have opened it?” Stheno asked.

“Immediately,” answered Euryale.

Medusa nodded. “Me, too.”

Stheno’s face hardened. She kept her eyes forward, locked on the disaster. “I wouldn’t. Never.”

An alarming, confusing rush of appreciation and frustration for her steadfast sister swept through Euryale’s chest. She wanted to hug her; she wanted to slap her. “You don’t always have to be so righteous.”

Medusa lay her head against Stheno’s shoulder. “We grant you permission to misbehave, Stheno. At least once.”

From the other side, Euryale nudged Stheno with her elbow. “Start a fight. Tell a lie. Spread a plague. Eat a baby.”

Medusa giggled.

“Leave me alone.”

“Because of Pandora, we have an opening to be as wicked as we want.”

“Stop blaming that girl,” Stheno rebuked.

Euryale drew back. “I didn’t know you were so attached.”

“I’m not, but this world wasn’t ruined by some clay girl and a silly vase.” Stheno clutched her hands together in her lap. “The wars between egos have always existed. Fathers kill their sons. Sons overthrow their fathers. And these battles will rage on for as long as too few hold too much power.”

Medusa and Euryale exchanged a look over Stheno’s head.

“We hear you,” Medusa told their sister.

“And you’re not wrong,” admitted Euryale.

A smile tugged at Stheno’s lips. “I’m more than that. I am right.”

The sisters sat quietly for a while, lost to their own thoughts, but Medusa could tolerate silence for only so long before commencing her sanguine chatter. She was like a bird in that way, chirping through the torrents. “Do you think there will be more humans?”

Euryale groaned. “I’m so bored of this conversation. I’ll rip every hair from my head if we talk about humans one more time.”

“Unlikely,” commented Stheno. “You are far too vain.”

“Although,” clarified Medusa, a puckish ring to her voice. “I’ve been told I have the best hair in this trio.”

Stheno laughed.

Euryale pursed her lips. “I would push you into this flood, but Echidna would save you.”

“And you’d miss me.”

Euryale scoffed but allowed Medusa to reach across their eldest sister to hold her hand.

“You’d miss me,” Medusa repeated.

Euryale didn’t answer, just let her focus drift slowly, naturally back to the horizon. To its shades of tempestuous blue: the watery mass grave moaning beneath a squally sky.

“You’ll miss me.”

* * *

DESPITE ZEUS’S BEST efforts, humanity survived.

Pandora’s daughter, Pyrrha, and Prometheus’s son, Deucalion, floated on a piecemeal ark to Mount Parnassus and began anew, throwing the rocks of Gaea over their shoulders to form another race of man and woman.

Such resilient creatures, Euryale thought with begrudging admiration. Like a decapitated reptile that immediately regrows its head.

With the generations that followed came an entirely new phenomenon: the city-state. Civilizations sprouted like wild amaranth, and they placed human names on these primal lands. Corinth and Argos. Attica. The large island became Crete, and it was there that Zeus, as a white bull, abducted the princess Europa.

Arguably, this became the moment Euryale acceded to humanity’s permanence. Now that Zeus had tasted the spoils—had capitalized on a new prurient venture—there would be no more natural disasters and mass killings. The gods were as hungry for maidens as they were for fresh stories.

Europa’s heroic brother, Cadmus, founded Thebes, a city-state of unparalleled dominance and influence in the land of Boeotia. The sisters collected whispers of the Cadmea, of the Spartoi, and repeated them to one another under the private veil of night. It was Medusa who first confessed: “I want to go.”

For Medusa was brave enough to voice what Euryale also desired. She could not swallow another acerbic lifetime clinging to the outskirts, as removed from the gilled and scaled as they were from the elite. In truth, the sisters made sense only when they were alone together, and Euryale would rather join the ranks of the Underworld than spend her eternity as a spinster.

“But why?” Ceto frowned, stroking the octopus nestled at her shoulder, tentacles draped across her being in a strange subterranean style. Once again, she exhibited more affection for some spineless, toxic creature than for her own daughters, and Euryale’s lips clamped down on a sudden gush of vitriol. Their infancy was a bitter recollection. On good days they were raised by whales, but Euryale was no animal. She despised Ceto for outsourcing her maternity, yet Euryale also knew that without a mammalian wet nurse, she and her sisters would have surely starved to death.

It was complicated and confusing, emotions that made Euryale irritable.

“Everybody visits, Mother,” Stheno offered simply.

“Well, it should be an easy assimilation. You three are so unremarkable.”

The Graeae lurked and listened, their very grayness blending them into the cave, and they smugly echoed Ceto’s insults:

“So humanlike already!”

“Could easily pass for mortals.”

“Especially Medusa.”

Ceto popped a prawn into her mouth like a berry, then spit its tail into a putrescent pile of fish bones beside her. Euryale set her jaw. Ceto affected airs, but she represented the lowest region of an august domain. Sea beasts were revolting, all scar tissue and barnacles, gelatinous tentacles and misshapen accretions, snaggleteeth in constant flux from the viciousness of eating.

Other water beings inspired praise. The salty Oceanids included the lovely, fishtailed Eurynome, who mothered the Graces. The Nereids—not just Amphitrite, but Thetis and Galatea—wore coral wreaths and white robes trimmed in gold. They danced barefoot with their father on a silvery grotto at the bottom of the sea, singing with melodious voices of bounty and breadth. And then there were the freshwater Naiads, who collected tributes for nursing the young, for guiding a human child’s passage to adulthood. They were the wives of kings, beloved of gods!

Ceto relished in reaping fear. She reveled in pain and horror, reviled beauty.

Euryale would rather be worshipped—she had been born to the wrong water family.

“They call Cadmus the first hero,” continued Stheno, in a futile attempt to sway their mother. Euryale wished she would stop.

“For slaying the dragon of Ares! One just like your brother!” Ceto leaned forward, hissing. “Your hero