7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Bringing together everything Rachel Caine has written in short form about Morganville, this collection is carefully organised into a timeline so you can read from the earliest adventures - some of which belong to vampires - all the way through to post-Daylighters, the final novel in the series. Midnight Bites includes more than 50,000 words of brand-new content, alongside stories compiled from the author's website and anthologies. Including 'Dead Man Stalking' and 'Pitch-Black Blues', these tales feature everyone's favourite bunny-slipper-wearing mad scientist, a fatal car crash, zombies, eerie carnival grounds, a blood-dispensing vending machine and much more. This diverse and supercharged group of stories will shine a little more light in the murkiest corners of Morganville.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

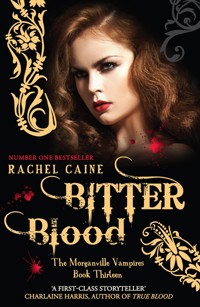

Praise for the Morganville Vampires series

‘Rachel Caine is a first-class storyteller who can deal out amazing plot twists as though she was dealing cards’ Charlaine Harris, author of the True Blood series

‘Thrilling, sexy, and funny! These books are addictive. One of my very favourite vampire series’ Richelle Mead, author of the Vampire Academy series

‘Rachel Caine’s Morganville Vampires series is my all-time favourite. I love love love the characters, the town, and the surprising plots’ Maria V. Snyder, New York Times bestselling author

‘We’d suggest dumping Stephenie Meyer’s vapid Twilight books and replacing them with these’SFX Magazine

‘Fast-paced adventure … Claire’s tough-girl attitude may remind adult readers of Rachel Morgan and her world of human-vampire interactions. A tremendously popular series’Booklist

‘Ms Caine uses her dazzling storytelling skills to share the darkest chapter yet … An engrossing read that once begun is impossible to set down’Darque Reviews

‘[Caine’s] imagination easily tops the average … Her suspense scenes, the heart of this series, crackle with vitality … This series continues to provide terrific action and great entertainment’Kirkus Reviews

‘A rousing horror thriller that adds a new dimension to the vampire mythos … An electrifying, enthralling coming-of-age supernatural tale’Midwest Book Review

Praise for Rachel Caine’s Weather Warden series

‘Murder, mayhem, magic, meteorology – and a fun read. You’ll never watch the Weather Channel the same way again’ Jim Butcher

‘The Weather Warden series is fun reading … more engaging than most TV’Booklist

‘A fast-paced thrill ride [that] brings new meaning to stormy weather’Locus

‘An appealing heroine, with a wry sense of humour that enlivens even the darkest encounters’SF Site

‘Fans of fun, fast-paced urban fantasy will enjoy the ride’SFRevu

‘Caine has cleverly combined the wisecracks, sexiness, and fashion savvy of chick lit with gritty action-movie violence and the cutting-edge magic of urban fantasy’Romantic Times

‘A neat, stylish, and very witty addition to the genre, all wrapped up in a narrative voice to die for. Hugely entertaining’SFcrowsnest

‘Caine’s prose crackles with energy, as does her fierce and loveable heroine’Publishers Weekly

‘As swift, sassy and sexy as Laurell K. Hamilton! … With chick lit dialogue and rocket-propelled pacing, Rachel Caine takes the Weather Wardens to places the Weather Channel never imagined!’ Mary Jo Putney

Midnight Bites

The Morganville Vampires

TALES OF MORGANVILLE

RACHEL CAINE

CONTENTS

(IN ORDER OF TIMELINE WITHIN THE SERIES)

WELCOME BACK TO MORGANVILLE

I never thought I’d get to say that, but after receiving many, many requests for some kind of collection of all the various short stories I’d written in the world of Morganville, I began to consider the idea of putting them all together … all the one-offs, exclusives, and Web stories. All the stories that were only published in certain languages, or countries.

But the one thing I did not want to do was just give you things you could (with great effort) put together for yourself. I needed to be sure you got good stuff. New stuff.

So there are included in this anthology, thanks to the incredible generosity of my six Kickstarter backers for the Web series of Morganville, six original tales for you to enjoy. These backers have hardcover editions of these stories in a special coffee-table collection, but they’ve been kind enough to let me share the Morganville love with all of you, too. So where those stories appear, you’ll see their names attached to them, with special thanks.

Each story has a little introduction and backstory with it, from me.

One final note: I resisted calling this The Complete Collection, because I don’t think I’m done with Morganville yet (or it isn’t done with me). Because, as you know, once you’re a Morganville resident … you’ll never want to leave.

– Rachel Caine, Midnight Bites

Introduction

This story came about just because I wanted to know more about Myrnin for my own understanding of his character, and sometimes, the best way to achieve that is to write a character’s history from his/her point of view. The character tells me what’s important, and what changed, for better or worse. Discovering that Myrnin’s father had some type of mental disorder was important to me, because of course when he was born, such things weren’t really understood. When I was working on the draft of the first book in which Myrnin appeared, my co-worker who read it said, ‘Oh, you’ve written a bipolar character, and he’s actually really cool! Did you know that I take medication for that?’ She went on to relate all the ways he was familiar to her. I was amazed, and honoured. I won’t name the co-worker, for privacy, but I say now, as then: thank you for sharing your story with me, and you know who you are. I hope Myrnin continues to make you proud.

MYRNIN’S TALE

I grew up knowing that I would go insane. My mother spared no chance to tell me so; I was, on regular occasions, walked up the road to the small, windowless shack with its padlocked door, and introduced to my dirty, filthy, rag-clad father, who scratched at the walls of his prison until his fingers bled, and whimpered like a child in the harsh glare of daylight.

I still remember standing there, looking in on him, and the hard, hot weight of my mother’s hand on my shoulder to keep me from running, either towards him or away from him. I must have been five years old, perhaps, or six; I was old enough to know not to show any sign of distress or weakness. In my household, distress earned you slaps and blows until your tears stopped. Weakness invited far worse.

I don’t remember what she told me on the first visit, but I do remember the ritual went on for years … up the road, unlocking the chains, rattling them back, shouting through the door, then opening it to reveal the pathetic monster within.

When I was ten, the visits stopped, but only because on that last occasion the door swung open to reveal my father dead in the corner of the hut, curled into a ball. He looked like a wax dummy, I thought, or something dug up in the bogs, unearthed after a thousand years of silent neglect.

He hadn’t starved. He’d expired of some fit, which no one found surprising in the least. He was buried in haste, with decent rites, but few mourners.

My mother attended the funeral, but only because it was expected, I thought. I can’t say I felt any differently.

After the burial, she took me aside and looked at me fiercely. We shared many things, my mother and I, but her eyes were brown, and mine were very dark, black in most light. That, I had from my father. ‘Myrnin,’ she said. ‘I’ve had an offer to apprentice you. I’m going to take it. It’s one fewer mouth to feed. You’ll be on your way in the morning. Say goodbye to your sisters.’

My sisters and I shared little except a roof, but I did as I was bid, exchanged polite, cold kisses and lied about how I would miss them. In none of this did I have a choice … not my family, nor my apprenticeship. My mother would be relieved to be rid of me, I knew that. I could see it in her face. It was not only that she wanted fewer children underfoot; it was that she feared me.

She feared I was like my father.

I didn’t fear that. I feared, in fact, that I would be much, much worse.

In the morning, a knock came at the door of our small cottage well before dawn. We were rural folk, used to rising early, but this was far too early even for us. My mother was drowsy and churlish as she pulled a blanket over her shoulders and went to see who it was. She came back awake and looking more than a little frightened, and sat on my small cot, which was separated a little from the bed in which my three sisters slept. ‘It’s time,’ she said. ‘They’ve come for you. Get your things.’

My things were hardly enough to fill out a small bundle, but she’d sacrificed part of the cheese, and some ends of the bread, and some precious smoked meat. I wouldn’t starve, even if my new master forgot to feed me (as I’d heard they sometimes did). I rose without a word, put on my leather shoes for travelling, and my woollen wrap. We were too poor to afford metal pins, so like my mother and sisters, I fastened it with a small wooden peg. It was the nicest thing I owned, the woollen wrap, dyed a deep green like the forest in which we lived. I think it had been a gift from my father, when I was born.

At the door, my mother stopped me and put her hands on my shoulders. I looked up at her, and saw something in her lined, hard face that puzzled me. It was a kind of fear, and … sadness. She pulled me into her arms and gave me a hard, uncomfortable hug, all bones and muscle, and then shoved me back to arm’s length. ‘Do as you’re told, boy,’ she said, and then pushed me out, into the weak, grey predawn light, towards a tall figure sitting on a huge dark horse.

The door slammed shut behind me, cutting off any possibility of escape, not that there was any refuge possible with my family. I stood silently, looking up, and up, at that hooded, heavily cloaked figure on the horse. There was a suggestion of a face in the shadows, but little else that I could make out. The horse snorted mist on the cold air and pawed the ground as if impatient to be gone.

‘Your name,’ the figure said. He had a deep, cultured voice, but something in it made me afraid. ‘Speak up, child.’

‘Myrnin, sir.’

‘An old name,’ he said, and it seemed he liked that. ‘Climb up behind me. I don’t like being out in the sun.’

That seemed odd, because once the sun rose, the chill burnt off; this was a fair season, little chance of snow. I noticed he had expensively tailored leather gloves on his hands, and his boots seemed heavy and thick beneath the long robes. I was conscious of my own poor cloth, the thin sandals that were the only footwear I owned. I wondered why someone like him would want someone like me … There were poor folk everywhere, and children were ten a spit for the taking. I stared at him for a long moment, not sure what to do. The horse, after all, was very tall, and I was not.

Also, the horse was eyeing me with a clear sense of dislike.

‘Enough of that, come on,’ my new master snapped, and held down his gloved hand. I took it, trying not to tremble too much, and before I could even think, he’d pulled me straight up onto the back of that gigantic beast, into a thoroughly uncomfortable position behind him on the hard leather pad. I wrapped my arms around him, more out of sheer panic than trust, and he grunted and said, ‘Hold on, boy. We’ll be moving fast.’

I shut my eyes, and pressed my face to his cloak as the horse lunged; the world spun and tilted and then began to speed by, too fast, too fast. My new master didn’t smell like anyone I’d ever known: no stench of old sweat, and only a light odour of mould to his clothes. Herbs. He smelt like sweet summer herbs.

I don’t know how long we rode – days, most certainly; I felt sick and light-headed most of the time. We did stop from time to time, to allow me to choke down water or bites of bread and meat, or for the more necessary bodily functions … but my new lord ate little, and if he was subject to the needs of the body, I saw no sign of it.

He wore the cloak’s hood up, always. I got only the smallest glimpses of his face. He looked younger than I would have thought – only ten years older than me, if that. Odd, to be so young and rumoured to have such knowledge.

I ached everywhere, in every muscle and bone, until it made me want to weep. I didn’t. I gritted my teeth and held on without a whimper as we rode, and rode, through misty cold mornings and chilly evenings and icy dark nights.

I had no eyes for the land around us, but even I could not mistake how it changed from the deep green forest to slowly rolling hills with spottings of trees and brush. I didn’t care for it, truth be told; it would be hard to hide out here.

On the morning when the fog lifted with the sun’s determined glare, my master drew rein and stopped us on a hilltop. Below was a valley, neatly sectioned into fields. Up the rise of the next hill sprawled an enormous dark castle, four square corners and jutting towers. It was the biggest thing I had ever seen. You could have put ten of my small villages inside the walls, and still had room for guests.

I must have made some sound of amazement, because my master turned his head and looked back at me, and for a moment, just a moment, I thought that the sunrise turned his eyes to a fierce hot red. Then it was gone, in a flash.

‘It’s not so bad,’ he said. ‘I hear you have a quick mind. We’ll have much to learn together, Myrnin.’

I was too sore and exhausted to even try to make a run for it, and he didn’t give me time to try; he spurred his horse on, down into the valley, and in an hour we were up the next hill, riding a winding, narrow road to the castle.

So began my apprenticeship to Gwion, lord of the place in which I was taken to learn my trade of alchemy, and wizardry, and what men today would call science. Gwion, you will not be surprised to hear, was no man at all, but a vampire, one older than any others alive at that time. His age surpassed even that of Bishop, who ruled the vampires in France with an iron hand until his daughter, Amelie, cleverly upended his rule.

But that’s tales for another day, and enough of this gazing into the mirror.

I am Myrnin, son of a madman, apprentice to Gwion, and master of nothing.

And content I am to be that.

Introduction

Dedicated to Teri Keas for her support for the Morganville digital series Kickstarter

This is the first of our original short stories in this collection, and again … it’s a tale of Myrnin, and his struggle to be the man (or vampire) that he wishes to be. It’s also a story of his first encounter(s) with the lady we come to know (in Bitter Blood and later books) as Jesse, the red-haired bartender, whose history is intertwined with both Myrnin’s and Amelie’s back in the mists of time. Though Lady Grey has her own story, and maybe sometime I’ll get around to telling that, too.

NOTHING LIKE AN ANGEL

He’d been in the dungeon a few months this time, or at least, he thought he had; time was a fluid thing, twisting and flowing and splitting into rivulets that ran dry. It was also circular, he thought, like a snake eating its tail. He’d had a cloak brooch once in that shape, in shimmering brass, all its scales hammered out in exquisite detail. The cloak had been dark blue, a very becoming thing, thick wool, lined with fur. It had kept him alive, once upon a time, in a snowstorm. When he’d been alive.

That had been one of the many times he’d tried to run away from his master. Of course, his master hadn’t needed a cloak, or fur, or anything to cover him when he came looking. His master could run all day and night, could smell him on the wind and track him like a wolf running down a deer.

And then eat him. But only a little, a bite at a time. His master was merciful that way.

It was cold in the dungeon, he thought, but like his old master, he no longer bothered with the cold now. The damp, though … the damp did bother him. He didn’t like the feel of water on his skin.

He’d been here for too long this time, he thought; his clothes had mostly rotted away, and he could see his blindingly white skin peeping through rents and holes in what had once been fine linen and exotic velvet. No telling what colour it had all been, when times were better … dark blue, like the cloak, perhaps. Or black. He liked blacks. His hair was dark, and his skin had once been a dusty tan, but the hair was a matted mess now, unrecognisable, and his skin was like moonlight with a coppery shimmer over the top. When he had enough to eat, it would darken again, but he’d been starving a long time. Rats didn’t help much, and he ached in his joints like an old, old man.

He didn’t really remember what he’d done to land here, again, in the dark, but he supposed it must have been something foolish, or egregious, or merely bad luck. It didn’t matter much. They knew what he was, and how to contain him. He was caged, like a rabbit in a hutch, and whether he would be meat for the table or fur to line some rich boy’s cloak, he had no choice but to wait and see.

Rabbits. He’d always liked rabbits, liked their whisper-soft fur and their curious, wiggling noses and their puffball tails. He’d had a pet rabbit when he was small, a brown thing that he’d saved from the hutch when it was just a baby. He’d fed it from his own scraps and hidden it away from his mother and sisters until it had got too big and his mother had taken it away and then there had been rabbit stew and he’d cried and cried and …

There were tears on his cheeks. He wiped them away and tried to push the thoughts away again, but like all his thoughts, they had a will of their own, they scampered and ran and screamed, and he didn’t know how to quiet them any more.

Maybe he belonged here, in the dark, where he could do no more damage.

No footsteps in the hall, but he heard the clank of a key in the lock, loud as a church bell, and it made him try to scramble to his feet. The ceiling was low, and the best he could manage was a crouch as he wedged himself into a corner, trying to hide, though hiding was a foolish thing to do. He was strong – he could fight – he should fight …

The glare of a torch burnt his eyes, and he cried out and shielded them. The silver chains on his hands clicked, and he smelt fresh burns as they seared new, fragile skin.

‘Dear God,’ whispered a voice, a new voice, a kind voice. ‘Lord Myrnin?’ She – for it was a she; he could tell that now – put the right lilt into the name. The horror in her tone knifed into him, and for a moment he wondered how bad he looked, to engender such pity. Such undeserved sympathy. ‘We learnt you were being held here, but I never imagined …’

His eyes adapted quickly to the new light, and he blinked away the false images … but she still shimmered, it seemed. Gold, she wore gold trim on her pale gown, and gold around her neck and on her slim fingers. Her hair was a red glory, braided into a crown.

An angel had come into his hell, and she burnt.

He did not know how to speak to an angel. After all, he’d never met one before, and she was so … beautiful. She’d said a name, his name, a name he’d all but lost here in the darkness. Myrnin. My name is Myrnin. Yes, that seemed right.

She seemed to understand his hesitation, because she advanced a step, bent, and put something down between them … then withdrew to the doorway again with her torch. What she’d put there on the stained stone floor drew his attention not so much for its appearance – a plain, covered clay jar – but for the delicious, unbelievable smell radiating from it like an invisible aura. Warmth. Light. Food.

He scrambled towards it like a spider, opened it, and poured the blood into his mouth, and it was life, life, sunlight and flowers and every good thing he had ever known, life, and he drained the jug to the last sticky drop and wept, clutching it to his chest, because he’d forgotten what it meant to be alive, and the blood reminded him of what he’d lost.

‘Hush,’ her voice whispered, close to his ear. She touched him, and he flinched away, because he knew how filthy he was, how ragged and beaten by his lot, where she was such a beautiful thing, so fine. ‘No, sir, hush now, all is well. I’m sent to bring you to safety. My name is Lady Grey.’

Grey did not suit her, not at all: such a nothing colour, neither black nor white, no lustre or flash to it. She was all fire and beauty, and no grey at all.

Some of his memory stirred, though, gossip overheard beyond his cell by those whose lives were lived beyond this stone. Lady Grey’s become the queen. She’ll not last long.

And then, the same voices. Lady Grey’s dead – what did I tell you? Chopped on the block. That’s what politics gets you, lads.

This was Lady Grey, but Lady Grey’s head had been chopped off, and hers was still attached.

He looked up, and like recognised like. The shine in her eyes, reflecting the torchlight. The hunger. The feral desire to live. She was like him, sugnwr gwaed, an eater of blood. A vampire. Interesting, that. He hadn’t thought a vampire could survive a beheading. Not an experiment he’d ever tried. Experiments, yes, he liked experiments. Tests. Trials. Learning the limits of things.

‘Lady Grey,’ he said. His voice sounded full of rust, like an old hinge all a-creak. ‘Forgive.’

‘No need for that,’ she said. ‘Let me see your hands.’

He held them out, hesitantly, and she made a sound of distress to see the burns that were on him beneath the silver manacles. She sorted through a thick ring of keys, found a silver one, and turned it in the lock. They fell apart, slipped free, and clanked heavily to the stone floor.

He staggered with the shock of freedom.

‘Can you walk, Lord Myrnin?’

He could, he found, though it was a clumsy process indeed, and his bare feet slipped on the mould of the stones. She was ruining her hems on the filth, he thought. She gave no thought to it, though, and when he reached her, she clasped him fast by the arm and gave him support he badly needed. Her other hand still held the torch, but she kept it well away from them both, which helped his eyes focus on her face, oh, her face, so lovely and well formed. A mouth made for smiling, though it seemed serious just now.

‘I am sorry,’ he said, and this time it seemed more expert, his forming of words. ‘I am in no shape to entertain visitors.’

She laughed, and it was like clear chimes ringing. It was a sound that made tears prick painfully. Hope could be a deadly thing, here. Torturous.

‘I am no visitor, and I hope this is not your home,’ she told him, and patted his arm gently before she took a firm hold again. ‘I am taking you out of here. Come.’

He looked around at this narrow stone hole that had been his home for so long. Nothing in it but the scratches he’d made in the stone, half-mad words and mathematics that led nowhere but in circles.

He went with her, into air that felt fresh and new. He could hear the weak moans and cries of others here, but she ignored them and led him up a long, shallow flight of stone steps to a door that hung open.

He stepped into a guard’s chamber, with a fire sizzling on the hearth and two men lying dead on the floor. Their dinner was still set on the table, and their swords lay unused in a corner. He knew these men, by smell if not by sight. They had been his captors for the past few months. They changed often, the gaolers. Perhaps they couldn’t bear to be down in the dark long, to think they were as trapped as their charges.

He smelt blood in them, and it was the same as coursed through his veins, filling him with strength. Lady Grey had bled them before she’d killed them.

He said nothing. She took him to another door, more stairs, more, until there was another portal that led to a cool, clear, open space.

They were outside. Outside. He stopped, all his senses overwhelmed with the night, the moon, the stars, the whispering breeze on his face. So much. Too much. It was only Lady Grey’s strong hand on his arm that kept him upright.

‘Almost there,’ she promised him, and pulled him on, stumbling and clumsy with the richness of freedom, to a pair of horses tethered nearby. Dark horses, hidden in the night, with muffles around any metal. ‘Do you think you can sit a saddle, my lord?’

He could. He mounted by memory, feet in stirrups, reins in hands that knew their task, and followed the glimmer of the lady’s dress into the darkness … which was, he realised, no darkness at all, to his quick-adapting eyes. Shades of blues and greys, colours muted but not hidden. The moon revealed so much … the castle’s bulk they were leaving behind, the empty fields around it, the clean white ribbon of the road they followed. The trees closed around them quickly, hiding them, and he felt, for the first time, that he was actually free again.

He didn’t know what it meant, really, but it felt good.

The ride lasted the night, and as the horizon began to take on a slow, low light, Lady Grey led him to a well-made hall … not a castle, nor yet a fortress, but something built for strength and purpose nevertheless. He did not know the design of it, but it felt safe enough.

There were no windows in it, save for shaded slits at the very top of the walls.

The gates parted for them as they rode to the entrance, and once inside, he realised there were men, not magic, involved: vampires like himself, dressed in plain black tunics and breeches, who had opened and then shut and barred them behind. The horses were led away without a word, off to some stables, and then they were walking into an inner keep, one built even more solid and strong, lit for vampire eyes.

‘Is this yours?’ he asked the lady still supporting his weight as they walked. ‘This place?’

‘It is one place of safety,’ she said. ‘I didn’t build it, nor do I own it. I suppose you may say it belongs to many. In time of need, we share our shelters.’ After a brief pause, she said, with what he thought might have been amusement, ‘You are quite filthy.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed. ‘Yes, I am.’

‘We’ll put you right.’

His angel took him to a room near the back of the stone keep … not spacious, but it had an angled slit for a window near the top, and though he had a bad moment of terror crossing the threshold, he found it had a feather bed in it, not just chains and pain. It had been so long, he wondered if he could even sleep in such a thing, but it was a terribly wonderful thing to have the chance to even think on it.

‘I will arrange for a bath,’ Lady Grey said, and pulled a chair from the corner that he had not even seen; so blinded had he been by the bedding. ‘Sit here. I’ll return soon.’ She hesitated at the door, with her hand on the latch, and he saw the compassion in her face. ‘I’ll leave this open, shall I?’

He nodded slowly, astounded she would comprehend so easily, and watched as she disappeared silently from the room. It was a dream, he decided. A lovely dream, a wonderful thing, but it would make it all the worse when he woke up to burning chains and locks and cold, empty stones. He’d rather not dream. Not hope. It was better to live in the dark.

He closed his eyes, willing himself to wake, but when he opened them again, nothing had changed. His body ached from the ride and the stretch of muscles unfamiliar to movement; his hunger was blunted, though not truly sated yet. Surely, if it was a phantasm, he’d have imagined himself free of pain and thirst. Wasn’t that the whole purpose of a dream?

He startled when Lady Grey appeared again in the doorway. She had changed her clothing to a plain pale gown, all jewellery and fine clothes put away. Over her arm, she had more clothing folded. She paused where she was, and smiled at him … a slow, warm thing, full of concern.

‘May I assist you?’ she asked him. He blinked, not certain how to answer, and then nodded, because he realised suddenly that it would be hard for him to stand on his own. Weakness was his constant companion now. He wondered if it would always be this way. Surely not. Vampires are not so weak.

Except he felt very weak indeed.

Her arm felt strong beneath his, and he leant against her as they walked the short distance to what must have been set aside as a bathing chamber. Within it sat a large copper tub, big enough to submerge a full-grown man if he was so brave, and on a three-legged stool beside it sat a pile of sheets to use as windings. There was even a thick liquid of soap in a pail; it smelt like lavender. The water was warm enough to steam the chilly air.

He had his shirt – what remained of it – half off his body when he remembered his good manners, and dropped it back over his pallid skin. ‘Forgive me, my lady,’ he said. ‘I—am not myself.’

‘And little wonder of that,’ she responded briskly. She was binding a piece of cloth over her red hair, which was now slung in a loose braid over her shoulder. ‘You must have help, Lord Myrnin. I am far from shy. Disrobe.’

‘I—’ He was utterly at a loss for words, and stared at her until her fiery eyebrows rose. She looked more imperious than any bathing attendant he could imagine. ‘It’s not fitting that you … a queen …’

‘A dead queen, well buried, and I never liked her. I’ve discovered quickly enough that this life gives me a freedom I never tasted before. I like it, I think.’ She flashed him a full, charming smile this time, and quirked one eyebrow higher. ‘I’ll turn my back if you give me your oath not to fall and dash your head open on the stones.’

‘I’ll try,’ he promised. She politely turned, and he stripped quickly, shocked at the sight of his own skin after so long but glad, so very glad, to have those stiff, evil rags off his body. Getting into the tub was a daunting challenge that he only just managed, and he raised quite a splash at the last as his feet slipped from under him to spill him into the water. It raised a gasp from him, and then a groan.

‘Is your modesty protected, sir?’ Lady Grey asked. She sounded as if she had difficulty keeping her laughter in check. Myrnin looked around, grabbed a small washing cloth, and draped it carefully over pertinent areas before he leant back against the living-skin-warm copper back of the tub.

‘It’s not modesty,’ he told her as she turned. ‘It’s politeness. I shouldn’t like to shock a lady such as yourself.’

‘I am never shocked. Not any more.’ She picked up his rags from the floor, frowned at them, and threw them into a heap in the corner. ‘Those we’ll burn. Clean clothing will be waiting when you are done. Shall I help you scrub?’

‘No!’ He sat up, almost drowning the floor in a wave of water, and pulled the pail of soap closer to scoop a handful out. ‘No, I will manage. Thank you.’

‘You’ll need assistance with that mange of hair,’ she said. ‘I can help with that, if nothing else.’

So it was that, despite his worry and discomfort, he found himself soaking his filthy hair beneath the water, then coming up to allow her to slather lavender soap into the tangled mess and scrub with merciless strength. It took a great deal longer than cleaning the rest of him. He no longer worried about his modesty; the bubbles that formed in the water, not to mention the filth clouding the bath, protected him well enough. Lady Grey had an impressive volume of curse words for a wellborn woman, but he thought she enjoyed the challenge more than he enjoyed the sometimes painful scrubbing.

When she judged him finally fit, she rubbed his hair from wet to damp, helped him stand, and wrapped the bathing sheet around him twice to sop up the water before she helped him out. Everything felt … different. His skin felt surprisingly soft, like a newborn’s. His hair was settling into clean waves; he’d forgotten it had that habit.

Most of all, what felt different was his own mind. Amazing that a little kindness, a little care, had settled his chaos so well.

Lady Grey was watching him with those striking, lovely eyes. He had no notion of what to say to her, except the obvious. ‘Thank you, my lady.’

‘My pleasure, my lord,’ she said, and curtsied just a bit. He responded with as much of a bow as he could manage in a bathing sheet. ‘She’s spoken of you often, you know.’

‘She?’ Myrnin paused in reaching for the black woollen breeches that she’d set out for him, and blinked at her.

‘Amelie,’ Lady Grey said.

‘Amelie?’

‘Our queen. She was concerned for you, and bid me find you. It took a good slice of time, but I am pleased you’re not as daft as I was told.’

‘Daft?’

‘However, you do repeat things quite a bit.’

‘I will bear it in mind.’

‘Please do.’ She gave him a look he could not even begin to interpret. ‘Shall I help you to dress?’

‘No!’ He must have sounded as scandalised as she hoped, for she gave him a saucy wink and left the room, closing the heavy oaken door behind her. He almost regretted her departure. She was … startling. Beautiful as an angel, tempting as something a great deal farther from heaven. Had Amelie intended for him to … no. No, of course not.

He felt vulnerable in the empty room. It was a hard thing to struggle into the clean clothes, but once he’d fastened them up, he felt far better. She’d even given him red felt shoes, lined with fur and festively embroidered. Amelie must have mentioned his fondness for the exotic.

Lady Grey was waiting in the hallway. She took him in at a long, sweeping glance, and he bowed again. ‘Do I meet your approval?’

‘Sirrah, you met my approval when I found you stinking and ill in a dungeon. You are bidding fair to be a heartbreaker now, though I must credit myself for the beauty of your locks.’ She winked at him and pulled the maid’s scarf from her head as she walked down the hallway. ‘Come. Your mistress will want to greet you, now that you’re half yourself again.’

‘Only half?’ he murmured.

‘I’ll have a meal waiting when you’re done. I expect that will restore you the rest of the way.’ She walked a few steps ahead, then turned towards him, still striding backward in an entirely unladylike manner. ‘Of course, restore you to what will be the question. Are you really a madman?’

‘It depends on the day of the week,’ he said. ‘And the direction of the wind.’

‘Clever little madman.’ She turned to finish her walk with absolute precision at the doors at the end of the hallway, which she thrust open with the confidence only a queen could possibly have. ‘My lady Amelie, I bring your errant wizard.’

‘Not a wizard,’ Myrnin whispered as he edged past her.

‘How disappointing,’ she whispered back, then bowed to Amelie and closed the doors, leaving him facing his old friend.

She was swathed in a dazzling white robe trimmed with ermine, intertwined most tellingly with strands of silver wire … She wanted her subjects to know that she was old enough and tough enough to defeat the burning metal, and therefore them. She looked the same as always: young, beautiful, imperious. She was reading a volume, and she placed a feather in it as a marker and set it aside as he bowed to her. He assayed a full curtsy, and almost fell in rising.

She was up and at his side instantly to assist him to a nearby chair. ‘Sit,’ Amelie said. ‘No ceremony between us.’

‘As you wish, my lady.’

‘I am not your lady,’ she said. ‘At the least, I do not raise the colour in your face the way our good Lady Grey seems to do. I’m pleased you enjoy her company. I hoped she might give you some … diversion.’

‘Amelie!’

She gave him a quelling look. ‘I meant that only in the most innocent sense. I am no panderer. You will find Lady Grey to be an intelligent and well-read woman. The English have no sense of value, to have condemned her so easily to the chop.’

‘Ah,’ he said, as she took her seat again. ‘How did she escape it?’

‘I found a girl of similar age and colouring willing to take her place, in exchange for rich compensation to her family.’ Amelie was cold, but never unfeeling. Myrnin knew she could have simply forced a hapless double for Lady Grey to go to her death, but she was kind enough to bargain for it. Not kind enough, of course, to spare a life, but then they were all killers, every one of them.

Even him. The trail of bodies stretched behind him through the years was something he tried hard not to consider.

‘Why rescue me now, Amelie?’ he asked, and fiddled with the ties on his shirtsleeves. The cloth felt soft on his skin, but he was unaccustomed to it, after so many years of wearing threadbare rags. ‘I’ve spent an eternity in that place, unremarked by you, and don’t tell me you didn’t know. You must need me for something.’

‘Am I so cruel as that?’

‘Not cruel,’ he said. ‘Practical, I would say. And as a practical ruler, you would leave me where you knew you could find me. I have a terrible habit of getting lost, as you well know. Since you chose to fetch me from that storehouse, you must have a job for me.’ It was hard to hold Amelie’s stare; she had ice-blue eyes that could freeze a man’s soul at the best of times, and when she exerted her power, even by a light whisper, it could cow anyone. Somehow, he kept the eye contact. ‘Do me the courtesy next time of storing me somewhere with a bed and a library, Your Majesty.’

‘Do you really think I was the one who imprisoned you? I was not. Yes, I knew you were there, but I had no one I could trust to go to you … and I could not go myself. It was not until the arrival of Lady Grey I felt I had an ally who would be up to the task should you prove … reluctant.’

‘You thought I’d gone completely mad.’ She said nothing, but she looked away. Amelie looked away. He swallowed and stared hard at his clasped hands. ‘Perhaps you weren’t so wrong. I was … not myself.’

‘I doubt that, since you are so much better already,’ Amelie said. Her tone was warm, and very gentle. ‘Tomorrow we will leave this place behind. I have a castle far in the mountains where you can work in peace to recapture all that you have lost. I am in need of a fine alchemist, and there is none better in this world. We have much to do, you and I. Much to plan.’

There was a certain synchronicity to it, he found; he had been in Amelie’s company for many years, and when he left it, disaster always struck. She was, in some ways, his lucky star. Best to follow her now, he supposed. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘I will go.’

‘Then you’d best say farewell to Lady Grey and find yourself some rest,’ she told him. ‘She will not come with us.’

‘No? Why not?’

‘Two queens cannot ever stay comfortably together. Lady Grey has her own path; we have ours. Say your goodbyes. At nightfall, we depart.’

She dismissed him simply by picking up her book. He bowed – an unnecessary courtesy – and saw himself out of the room. It was only as he shut the doors that he saw her guards standing motionless in the darker corners of her flats; she was never unwatched, never unprotected. He’d forgotten that.

Lady Grey was waiting for him, hands calmly folded in a maidenly sort of posture that did not match her mischievous smile. ‘Dinner,’ she said. ‘Follow me to the larder.’

The larder was stocked with fresh-drawn blood; he did not ask where it came from, and she did not volunteer. She sipped her own cup as he emptied his, drinking until all the screaming hunger inside was fully drowned. ‘Do you ever imagine you can hear them?’ he asked her, looking at the last red drops clinging to the metal goblet’s sides.

‘You mean, hear their screams in the blood?’ Lady Grey seemed calm enough, but she nodded. ‘I think I might, sometimes, when I drink it so warm. Odd, how I never hear it when they’re dying before me in real life. Only when I drink apart from the hunt. Is that normal, do you think?’

‘Whatever is normal in this world, we have no part in it,’ he said. ‘How long was I in the dark, my lady?’

‘Ten months.’

‘It seemed longer.’

‘No doubt because it was so congenial.’

‘You should have stayed for the formal procession of the rats. Very entertaining; there were court dances. Although perhaps I imagined it in one of my hallucinations. I did have several vivid ones.’

She reached across the table and wrapped her long, slender fingers around his hand. ‘You are safe now,’ she told him. ‘And I will keep my eye on you, Lord Myrnin. The world cannot lose such a lovely head of hair.’

‘I will try to keep my hair, and my head, intact for you.’ She’d kept her hand on his, and he turned his fingers to lightly grip hers. ‘I am surprised to find that you accept Amelie’s orders.’

Lady Grey laughed. It was a peal of genuine amusement, too free for a well-bred young woman, but as she’d said, she’d buried that girl behind her. ‘Amelie asks favours of me. She doesn’t order me. I stay with you because I like you, Lord Myrnin. If you wish, I’ll stay with you today, as you rest. It might be a day of nightmares for you. I could comfort you.’

The thought made him dizzy, and he struggled to contain it, control it. His brain was chattering again, running too fast and in too many wild directions. Perhaps he’d overindulged in the blood. He felt hot with it. ‘I think,’ he said finally, ‘that you are too kind, and I am too mad, for that to end well, my lady. As much as I … desire comfort, I am not ready for it. Let me learn myself again before I am asked to learn someone else.’

He expected her to be insulted; what woman would not have been, to have such a thing thrown in her face? But she only sat back, still holding his hand, and regarded him for a long moment before she said, ‘I think you are a very wise man, Myrnin of Conwy. I think one day we will find ourselves together again, and perhaps things will be different. But for now, you are right. You should be yourself, wholly, before you can begin to think beyond your skin again. I remember my first days of waking after death. I know how fragile and frightening it was, to be so strong and yet so weak.’

She understood. Truly understood. He felt a surge of affection for her, and tender connection, and raised her hand to his lips to kiss the soft skin of her knuckles. He said nothing else, and neither did she. Then he bowed, rose, and walked to his own chambers.

He bolted the door from within, and crawled still clothed between the soft linen sheets, drowning in feathers and fears, and slept as if the devil himself chased the world away.

As he rode away that night in Amelie’s train of followers, he looked back to see Lady Grey standing like a beacon on the roof of the stone keep. He raised a hand to her as the trees closed around their party.

He never saw her return the salute … but he felt it.

Someday, he heard her say. Someday.

He didn’t see her for another three hundred years. Wars had raged; he’d seen kingdoms rise and fall, and tens of thousands bleed to death in needless pain over politics and faith. He’d followed Amelie from one haven to the next, until they’d quarrelled over something foolish, and he’d run away from her at last to strike out on his own. It was a mistake.

He was never as good when left to his own devices.

In Canterbury, in England, at a time when the young Victoria was only just learning the weight of her crown, he made mistakes. Terrible ones. The worst of these was trusting an alchemist named Cyprien Tiffereau. Cyprien was a brilliant man, a learned man, and Myrnin had forgotten that the learned and brilliant could be just as treacherous as the ignorant and stupid. The trap had caught him entirely by surprise. Cyprien had learnt too much of vampires, and had developed an interest in what use might be made of them … medical for a start, and weapons for the future.

Confessing his own vampire nature to Cyprien, and all his weaknesses, had been a serious error.

I should have known, he thought as he sat in the dark hole of his cell, fettered at ankles, wrists, and neck with thick, reinforced silver. The burning had started as torture, but he had adjusted over time, and now it was a pain that was as natural to him as the growing fog in his mind. Starvation made his confusion worse, and over the days, then weeks, the little blood that Cyprien had allowed him hadn’t sustained him well at all.

And now the door to his cell was creaking open, and Cyprien’s lean, ascetic body eased in. Myrnin could smell the blood in the cup in Cyprien’s hand, and his whole body shook and cramped with the craving. The scent was almost as strong as that of the hot-metal blood in the man’s veins.

‘Hello, spider,’ Cyprien said. ‘You should be hungry by now.’

‘Unchain me and find out, friend,’ Myrnin said. His voice was a low growl, like an animal’s, and it made him uneasy to hear it. He did not want to be … this. It frightened him.

‘Your value is too great, I’m afraid. I can’t allow such a prize to escape now. You must think of all there is to learn, Myrnin. You are a man with a curious mind. You should be grateful for this chance to be of service.’

‘If it’s knowledge you seek, I’ll help you learn your own anatomy. Come closer. Let me teach you.’

Cyprien was no fool. He placed the cup on the floor and took a long-handled pole to push it within reach of Myrnin’s chained hands.

The red, rich smell of the blood overwhelmed him, and he grabbed for the wooden mug, raised it, and gulped it down in three searing, desperate mouthfuls.

The pain hit only seconds later. It ripped through him like pure lightning, crushed him to the ground, and began to pull his mind to pieces. Pain flayed him. It scraped his bones to the marrow. It ripped him apart, from skin to soul.

When he survived it, weeping and broken, he became slowly aware of Cyprien’s presence. The man sat at a portable desk, scratching in a small book with a feather pen.

‘I am keeping a record,’ Cyprien told him. ‘Can you hear me, Myrnin? I am not a monster. This is research that will advance our knowledge of the natural world, a cause we both hold dear. Your suffering brings enlightenment.’

Myrnin whispered his response, too softly. It hardly mattered. He’d forgotten how to speak English now. The only words that came to his tongue were Welsh, the language of his childhood, of his mother.

‘I didn’t hear,’ Cyprien said. ‘Can you possibly speak louder?’

If he could, he didn’t have the strength, he found. Or anything left to say. Words ran away from him like deer over a hillside, and the fog pressed in, silver fog, confused and confusing. All that was left in him was rage and fear. The taste of poisoned blood made him feel sick and afraid in ways that he’d never imagined he could bear.

And then it grew worse. Myrnin felt his arms and legs begin to convulse, and a low cry burst out of his throat, the wordless plea of a sick creature with no hope.

‘Ah,’ his friend said. ‘That would be the next phase. How gratifying that occurs with such precise timing. It should last an hour or so, and then you may rest a bit. There’s no hurry. We have weeks together. Years, perhaps. And you are going to be so very useful, my spider. My prized subject. The wonders we will create together … just think of it.’

But by then, Myrnin could not think of anything. Anything at all.

The hour passed in torment, and then there were a few precious hours of rest before Cyprien came, again.

The day blurred into night, day, night, weeks, months. There was no way to tell one eternity from the next. No time in hell, Myrnin’s mind gibbered, in one of his rare moments of clarity. No clocks. No calendars. No past. No future. No hope, no hope, no hope.

He dreaded Cyprien’s appearances, no matter how hungry he became. The blood was sometimes tainted, and sometimes not, which made it all the worse, of course. Sometimes he did not drink, but that only made the next tainted drink more powerful.

Cyprien was patient as death himself, and as utterly unmoved by tears, or screams, or pleas for mercy.

Time must have passed outside his hell, if not inside, because Cyprien grew older. Grey crept into his short-cropped hair. Lines mapped his face. Myrnin had forgotten speech, but if he could have spoken, he would have laughed. You’ll die before me, old friend, he thought. Grow old and feeble and die. The problem was that on the day that Cyprien stopped coming and lay cold in his grave, Myrnin knew he would go on and on, starving slowly into an insanely slow end, lost in this black hole of pain.

And finally, one day, Myrnin became aware that Cyprien had not come. That time had passed, and passed, and the darkness had never altered. Blood had never arrived. His hunger had rotted whatever sanity he had left, and he crouched in the dark, mindless, ready for whatever death he could pray to have … until the angel came.

Ah, the angel.

She smelt of such pale things … winter, flowers, snow. But she glowed and shimmered with colour, and he knew her face, a little. Such a beautiful face. So hard to look upon, in his pain and misery.

She had keys to his bonds, and when he attacked her – because he could not help it, he was so hungry – she deftly fended him off and gave him a bottle full of blood. Fresh, clean, healthy blood. He gorged until he collapsed on the floor at her feet, cradling the empty glass in his arms like a favourite child. He was still starving, but for a precious moment, the screaming was silent.

Her cool fingers touched his face and slid the lank mess of his hair back.

‘I find you in a much worse state this time, dear one,’ said the angel. ‘We must stop meeting like this.’

He thought he made a sound, but it might have been only his wish, not expressed by flesh at all. He wanted to respond. Wanted to weep. But instead he only stayed there, limp on the ground, until she pulled him up and dragged him out with her.

Light. Light and colour and confusion. Cyprien dead on the stairs, the cup of poisoned blood spilt into a mess on the steps next to his body. The bloodless bite on his neck was neat, and final.

There was a book in his pocket. That book. The book in which he’d recorded all of the torture, the suffering. Myrnin pointed to it mutely, and the angel silently slipped the book from Cyprien’s body and passed it to him. He clutched it to his breast. And then, with the angel’s help, stamped his foot down on the wooden mug to smash it into pieces.

‘I killed him for you,’ the angel said. There was tense anger in her voice, and it occurred to him then that her hair was red, red as flame, and it tingled against his fingers when he hesitantly stroked it. ‘He deserved worse.’ She stopped, and looked at him full in the face. He saw her distress and shock. ‘Can you not speak, sir? At all? For me?’

He mutely stared back. There was a gesture he should have made, but he could not remember what it would be.

She sounded sad then. ‘Come, let’s get you to safety.’

But there was no safety, out in the streets. Only a blur of faces and shrieking and pain. A building burnt, sending flames jetting like blood into the sky, and there was a riot going on, and he and his angel were caught in the middle of it. A man rushed them, face twisted, and Myrnin leapt for him, threw him down on the rough cobbles, and plunged his fangs deep into the man’s throat.

As good as the fresh blood his angel had delivered had been, this, this was life … and death. Myrnin drained his victim dry, every drop, and was so intent on the murder of it that he failed to see the club that hit him in the back of the head, hard enough to send him collapsed to the paving. More men closed in, a blur of fists and feet and clubs, and he thought, I escaped one hell to suffer in another, and all he could do was hug the book, the precious book of his own insanity and suffering, to his chest and wait to die.

But then his angel was there, his fiery angel. She needed no sword, only her own fury, and she cleared them from him. She was hurt for it, and he hated himself that he was the cause of her pain, but she drove them back.

The head wound must have sparked visions, because he saw himself, a different self, sober and sane and dressed in brilliant colours, and he saw himself in embrace with his angel – no, his Lady Grey, his saviour, he remembered her name now. He remembered that much, at least.

The book was gone. He did not know where he’d put it. But somehow it didn’t seem so important now. He had her. Her.

The vision vanished, and then Lady Grey turned to him, with something strange in her wide eyes as she helped him to his feet.

‘Come, my lord,’ she said. ‘Let us have you out of this place.’

Escape was difficult to achieve, but she changed from her blood-spattered gown and wrapped him in layers of heavy clothes, then hired a carriage to rush them out of London. The streets were unsafe around them, and he was, he admitted, not the most pleasant of companions. The filth on him had been unnoticeable when he was locked away, but now, with the clean smell of the countryside washing through the windows, and Lady Grey in her neat dress seated across from him, he knew he stank horribly. As neither of them breathed to live, though, it was a tolerable situation. For now.

But in addition to the filth, he was also given to fits, and he knew they distressed her. Sometimes he would simply leave his body while it thrashed hard enough to snap his bones; sometimes, the fit came as a wave of terror that drove him to cower in the footwell of the coach, hiding from imaginary agonies. And each time such things came to devour him, she was there, holding his hand, stroking his foul and filthy hair, whispering to him that all was well, and she would look after him.

And he believed her.

The trip was very long, and the fits passed slowly, but they lessened in intensity as his vampire body rejected Cyprien’s poisons from it; he slept, drank more blood, ate a little solid food (though that experiment proceeded less well), and felt a very small bit better when the carriage finally rocked to a stop at the ruins of an ancient keep set atop a hill.

‘Where are we?’ he asked Lady Grey, gazing at the old stones. They seemed familiar to him. She looked at him with a sudden, bright smile.

‘That’s the first you’ve spoken,’ she said. ‘You’re getting better.’

Was he? He still felt hollow inside as a bell, and yet full of darkness. At least there were words in him now. Yes. That was true.

‘You will remember this place,’ she said. ‘Come. It looks worse than it is.’

She must have paid the driver off, or bewitched him, because the coach thundered off in a cloud of dust and left them in the moonlight beside what seemed a deserted pile of tumbledown walls … and then he blinked, and the ruins wavered like the shimmer of heat over sand, and rebuilt into what the keep would have been, in its prime. Small but solid.

And he did know it. He’d visited it often in his dreams, trapped in Cyprien’s cells.

‘I remember,’ he said. ‘I had a bath.’

‘And you’ll have another, for all our sakes,’ Lady Grey said, and linked her arm in his. ‘Can you walk?’

‘Yes,’ he said. His voice sounded rusty and uncertain, but his will was strong, and he put one clumsy foot before another as she walked him forward. The gate opened as they approached, and servants bowed them in.

One of them, a tall, lean man, approached and said, ‘Shall I take him and see him presentable, my lady?’