Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Dark Masters

- Sprache: Englisch

From provincial obscurity to one of the most famous writers of his day.

Das E-Book My Fairy-Tale Life wird angeboten von Dedalus und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1043

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedalus would like to thank The Danish Arts Council’s Committee for Literature and Arts Council England, London for their assistance in producing this book.

The Translator

W. Glyn Jones read Modern Languages at Pembroke College Cambridge, with Danish as his principal language, before doing his doctoral thesis at Cambridge. He taught at various universities in England and Scandinavia before becoming Professor of Scandinavian Studies at Newcastle and then at the University of East Anglia. He also spent two years as Professor of Scandinavian Literature in the Faeroese Academy. On his retirement from teaching he was created a Knight of the Royal Danish Order of the Dannebrog.

He has written widely on Danish, Faeroese and Finland-Swedish literature including studies of Johannes Jørgensen, Tove Jansson and William Heinesen.

He is the author of Denmark: A Modern History and co-author with his wife, Kirsten Gade, of Colloquial Danish and the Blue Guide to Denmark.

His translations from Danish include My Fairy-Tale Life by Hans Christian Andersen, Seneca by Villy Sørensen and for Dedalus The Black Cauldron, The Lost Musicians, Windswept Dawn, The Good Hope and Mother Pleiades by William Heinesen, Ida Brandt by Herman Bang and Barbara by Jørgen-Frantz Jacobsen.

He is currently translating As the Trains Pass By (Katinka) by Herman Bang.

Contents

Title

Dedication

The Translator

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Copyright

Introduction

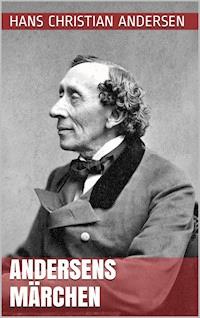

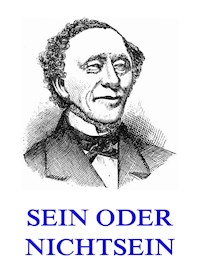

“Fiction and faction”, this contemporary adaptation of the title of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous autobiography Dichtung und Wahrheit (1811–33) can also be applied to the autobiography of the Danish fairy tale writer and story teller Hans Christian Andersen entitled My Fairy-Tale Life from 1855. This title, in fact, encompasses precisely the same two elements, “fiction” (“The Fairy Tale”) and “faction” (“Life”). Thus, we do, of course, find in Andersen’s autobiography basic information about his life. This information, however, must be read with a grain of salt as Andersen tended to arrange and re-arrange, even to fictionalize events to fit his concept of life as a fairy tale composed by God. Furthermore, in 1855 he had reached the apex of his career, which had made the son of a poor shoemaker a famous European celebrity dining with kings and queens all over Europe. So, naturally, he wished to present his life in the most advantageous light according to his well-known statement: “First, you have a terrible amount of adversity to go through, and then you become famous.” The fictitious element of My Fairy-Tale Life, however, can also apply to the fact that Andersen not only presents the biographical facts but time and again intersperses his prose with beautiful passages of descriptive and, occasionally, poetic prose.

There are numerous sources of information about Andersen, not only of general biographical nature, but also about the author as a visitor and explorer in foreign places and about what they could offer him as a traveller and an artist. Furthermore, one must keep in mind that Andersen was the greatest traveller of his time, going abroad 30 times in all to countries as far away as Turkey and Morocco in an age when travelling could be not only a demanding experience but outright dangerous. He left behind several autobiographies, extensive diaries, pocket calendars and a vast array of letters. Taken together they contain innumerable facts and details which provide us with an almost day-by-day account of what he saw, read and did, his opinions and innermost thoughts.

At the core of this material we have, of course, his autobiography from 1855, which, however, is not his only autobiography. Andersen’s first attempt, entitled Levnedsbogen (The Book of my Life), was written in 1832 and ends with a detailed, psychologically penetrating account of his relationship with his first love, Riborg Voigt. It was intended for publication in the case of his premature death, and her family name was deliberately omitted by Andersen. For many years the manuscript was thought to have been lost. It was found in the Royal Library in Copenhagen and published in 1926. For a planned German edition of his collected works Andersen wrote another autobiography, published in 1847 as Das Märchen meines Lebens ohne Dichtung. Already the same year an English edition, The True Story of My Life, was published in London and immediately afterwards reprinted in the United States. The Danish edition, Mit eget Eventyr uden Digtning (My Own Fairy Tale without Poetizing) did not appear until 1942! The German autobiography was finally expanded by Andersen and published in Danish in 1855 as Mit Livs Eventyr (My Fairy-Tale Life). It is this text which is presented here in English in a new translation by the Andersen scholar W. Glyn Jones.

My Fairy-Tale Life opens with the well-known statement, which clearly reveals Andersen’s worldview as well as his writing strategy: “My life has been a beautiful fairy tale, so abundant and so marvellously happy. The story of my life will tell the world what it tells me: that there is a loving God who directs all things for the best”, from the outset a clear indication of an intended idealization of his life and career as likewise presented in the famous autobiographical tale about “The Ugly Duckling” that – after having suffered so much adversity and cruelty – finally emerges as the beautiful white swan admired by the whole world.

Thus already the initial description of his childhood in the provincial town of Odense, where Andersen was born on April 2, 1855, contains disinformation about his family background, hiding the fact that it was marked by promiscuity and alcoholism. In a confidential letter to a friend in 1833 he, more precisely, calls himself “a swamp plant”.

In My Fairy-Tale Life we read about Andersen’s first attempts – when he was only 14 years of age and without money and education – at gaining a foothold in the Danish capital Copenhagen, his first attempts as a writer and his reactions to any negative criticism, which hurt him beyond rhyme and reason. We can admire his persistency in not giving up and returning to Odense, instead securing personal and financial support for his endeavours. Andersen would never give up because, in the final account, he felt that a “loving God” would help him. We follow him in his way towards recognition, through his many affairs of the heart. Riborg Voigt was only the first in a series of unhappy love stories. Andersen was a typical romantic in as much as one gets the impression that he was more in love with his love than with the woman in question. On the other hand, he is immensely discreet when it comes to the many carnal temptations he suffered, when travelling abroad in particular in southern Europe. There is, however, no doubt about his sincerity when he expresses his affection for the famous Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, whom he met for the first time in 1840. She undoubtedly served as a role model as well as the artistic inspiration for the magnificent tale about true art, “The Nightingale”. Undoubtedly, Jenny Lind was Andersen’s greatest love, even though in My Fairy-Tale Life he is rather discreet about his feelings for her. However, nothing came of this relationship either, but Andersen established friendships with numerous other women and men who cared for him and admired him as a writer and a human being.

Andersen’s journeys abroad frequently served as a remedy for unrequited love, and as a traveller he was in his natural element. But to travel was for him not just an escape from home, neither was it the urge felt by a young man from the provinces to see the big world, but a scrupulously planned educational trip which took him to the art treasures of Europe – in Berlin, Paris, Dresden, Vienna, Florence and Rome. Over the years Andersen developed an impressively unerring but also critical taste with regard to painting, sculpture, theatre and music.

Like the ugly duckling he was driven by an elementary curiosity, but to travel was for Andersen even more discovering a new world beyond the duck yard. It became just as important to him to use his travel experiences and impressions as sources of inspiration for his writing. In his diaries, which above all were travel diaries, he painstakingly wrote down all his observations, which later, either directly or artistically reworked, were utilized in his works including My Fairy-Tale Life. But not only did he record his longing to go abroad and his exuberance while en route, but he also expressed his misgivings and depression when realizing that he also had to return home to the duck yard, where according to his perception, petty and unprofessional criticism was all that awaited him.

For My Fairy-Tale Life is also a unique documentation of Andersen’s extreme vulnerability, his vanity and his insatiable craving for recognition, features of his personality which remained present until his death on August 4, 1875. They were, of course, rooted in his social background and ensuing insecurity, which made him a permanent outsider in the upper-class and aristocratic milieus in which he moved. On almost every page of his autobiography we sense his restlessness, his vanity, his urge to make acquaintances and to be accepted by others in order to overcome his social trauma. A hectic social life, successful recitals, friendships with internationally known artists and writers, and visits to royal courts all over Europe alternate with expressions of loneliness and dejection that hardly bear evidence of the direction of divine guidance that Andersen calls upon time and again and clearly did not want to be without. His memory was quite literally fabulous and his style exquisite. In his autobiography he combines these two qualities into a piece of literary art which is truly unique (in world literature), and which makes the reading of Hans Christian Andersen’s My Fairy-Tale Life such a delightful and captivating experience.

Sven Hakon Rossel

University of Vienna

I

My life has been a wonderful fairy tale, so abundant and so marvellously happy. Even if I had met a good fairy when I went out into the world poor and friendless as a boy, and she had said, “Choose your own way in life and the goal you want to achieve, and then, according to how your mind develops and as things will probably go in the world, I will guide and defend you,” my fate could not have been more wisely and happily and better directed. The story of my life will tell the world what it tells me: that there is a loving God who directs all things for the best.

In the year 1805 there lived in a tiny, mean room in Odense a newly married couple who were terribly fond of each other; he was a young shoemaker, scarcely twenty-two years old, a remarkably gifted man of a truly poetic bent, while his wife, a few years older than himself, knew nothing of life or the world, but was kind to the bottom of her heart. Shortly before this, the young man had become an independent master cobbler and had built his own workshop as well as the bridal bed. This bed was made from the wooden frame which only a short time previously had supported the coffin of the late Count Trampe as he lay in state, and the remnants of the crape that had adorned the woodwork were a reminder of this. Instead of a noble corpse, surrounded by crape and candelabras, there lay here on the second of April, 1805 a living, crying child. It was I, Hans Christian Andersen.

During the first days of my life my father is said to have sat by my mother’s bed reading passages from Holberg to her while I continued to squall out at the top of my voice. “Will you go to sleep or else be quiet and listen?” I have been told my father joked; but I still went on crying; and especially in church, when I was taken to be baptised, I cried so loudly that the parson, who my mother always said was an irritable man, exclaimed, “That child sounds like a cat yowling!” Words my mother never forgave him for. However, a poor French immigrant by the name of Gomard, who acted as godfather to me, consoled her by saying that the louder I cried as a child, the more beautifully I would sing as I grew older.

The home where I spent my childhood was one single little room where almost all the space was taken up by the workshop, the bed and the settle on which I slept. The walls, however, were covered with pictures; on the chest of drawers there were some pretty cups, glasses and bric-a-brac, and above my father’s bench there was a shelf containing books and songs. There was a plate-rack full of tin plates over the cupboard in the little kitchen which always seemed lovely and spacious. The door itself had a panel decorated with a landscape painting, and it meant as much to me then as a whole picture gallery now.

By means of a ladder it was possible to go from the kitchen on to the loft, and there, in the gutters between it and the neighbour’s house, stood a box of soil with chives and parsley growing in it; this was all the garden my mother possessed, and in my story The Snow Queen that garden still blooms.

I was an only child and was extremely spoiled, but my mother constantly told me how very much happier I was than she had been, and that I was being brought up like the son of a count. As a small child, she had been sent out by her parents to beg, and as she was not able to do it she had sat weeping a whole day long under a bridge over the river at Odense. I could see this so clearly in my childish imagination, and I wept over it. In old Domenica in The Improvisatore and in Christian’s mother in Only a Fiddler I have given two different versions of her character.

My father, Hans Andersen, let me have my own way in everything. I possessed his whole heart; he just lived for me. So on Sundays, the only free day he had, he spent all his time making toys and pictures for me. In the evening he would often read aloud to us from Lafontaine’s Odd Enough, To Be Sure, from Holberg and from The Arabian Nights. It is only in such moments as these I remember having seen him smile, for he was never really happy in his life as an artisan.

His parents had been wealthy country people, but misfortunes had showered down upon them: their cattle died, their farmhouse was burned down, and finally the husband lost his reason. After this, his wife moved to Odense with him, and there she apprenticed her intelligent son to a shoemaker. There was no other way, although it was his ardent desire to go to the grammar school. A few well-to-do citizens had at one time spoken of joining to ensure free board for him and so to give him a start in life, but nothing came of it. My poor father never saw his dearest wish fulfilled, but he never forgot what it had been. I remember that once, as a child, I saw tears in his eyes when a scholar from the grammar school came to our house to order a pair of new boots and showed us his books and told us what he was learning. “That’s the way I ought to have gone, too,” said my father. He kissed me affectionately, and then he was silent for the rest of the evening.

He rarely associated with his peers, but his relatives and friends came to visit us. As I have already said, he read aloud or made toys for me in the evenings in winter; in the summer he would go for a walk in the woods almost every Sunday and take me with him. He did not talk much out there, but sat in silent thought while I ran about gathering strawberries on a straw or tying garlands. Only once a year, in May when the woods had just come into leaf, did my mother go with us. It was the only occasion each year when she went for a walk for pleasure, and then she wore a flowered dress of brown calico which she only donned on these occasions and when she went to Holy Communion; so it is the only dress I remember in all those years as her best frock. Then when we went home after our walk in the woods she always took with her an armful of birch branches, which were then put behind our polished stove. We always put sprigs of St. John’s wort into the chinks of the beams and from the way in which they grew we could see whether our lives would be long or short. We decorated our little room with green branches and pictures, and my mother kept it neat and clean; she always took great pride in making sure that the bed linen and curtains were snow-white.

One of the first things I remember, of little importance in itself, but of great significance for me because of the way my childish fancy impressed it on my mind, was a family party, and where do you think it was? It was in the one place in Odense, in the one building which I always looked on with fear and trembling, just as children in Paris must have looked on the Bastille. It was in Odense Prison. My parents knew the gaoler there, and he invited them to a family dinner; I was to go, too. I was still so little at that time that I had to be carried home, as will be seen shortly. Odense Prison was for me the centre of stories about thieves and robbers; I often stood, although of course always at a safe distance, listening to the men and women inside singing as they sat at their spinning wheels.

I went to the gaoler’s party together with my parents; the great, iron-barred gate was opened and locked again with the key from the clanging bunch; we went up a steep staircase. We ate and drank and were waited on by two of the prisoners. I could not be brought to taste anything, and I pushed even the sweetest things away from me. My mother said I was ill and I was laid on a bed. But I could hear the spinning wheels humming nearby and merry singing, whether it was in my imagination or in reality I cannot tell, but I do know that I was afraid and on edge all the time; and yet it was pleasant to lie there and imagine I had entered the robbers’ castle. When my mother and father went home late that evening they carried me; it was a rough night, and the rain dashed against my face.

In my earliest childhood, Odense itself was quite a different town from what it is now that it has beaten Copenhagen with its street lighting and running water and I don’t know what else. In those days I think it was a hundred years behind the times; a whole lot of customs and traditions were still observed there, which had long since disappeared from the capital. When the guilds “removed their signs” they went in procession with flying banners and with lemons and ribbons on their swords. A harlequin with bells and a wooden sword ran merrily ahead of them; one of them, an old fellow called Hans Struh, made a great impression with his merry chatter and a face that was painted black, except for his nose which was allowed to keep its natural, bright red colour. My mother was so delighted with him that she tried to convince us that he was a distant relative of ours, admittedly very distant, but I still clearly remember that, with all the pride of an aristocrat, I protested against any relationship with the “fool”.

On Carnival Day the butchers used to lead a fat ox through the streets; it was decorated with garlands of flowers; a boy in a white shirt and wearing wings rode on it. The seamen also paraded through the streets at carnival time with a band and all their flags flying, and finally the two most spirited of them had a wrestling-match on a plank placed between two boats. The one who did not fall into the water was the winner.

But what was particularly fixed in my memory and was often revived by repeatedly being talked of, was the time when the Spaniards were in Funen in 1808. Denmark had entered into an alliance with Napoleon on whom Sweden had declared war, and before we knew where we were a French army with Spanish auxiliaries (under the command of Marshal Bernadotte, Prince of Pontecorvo) was stationed in the middle of Funen in order to cross to Sweden. I was not more than three years old at the time, but I can still clearly remember the row those dark brown men made in the streets, and the cannon that were fired on the market-place and in front of the bishop’s residence. I saw the foreign soldiers stretching out on the footpaths and on bales of straw in the half-ruined Greyfriars Church. Kolding Castle was burned down, and Pontecorvo came to Odense, where his wife and son Oscar were staying. In the surrounding countryside schools had been turned into guardrooms, and Mass was celebrated under the great trees in the fields and by the roadside. The French troops were said to be haughty and arrogant, the Spanish good-natured and friendly, and a fierce hatred existed between them; the poor Spaniards gained the most sympathy. One day a Spanish soldier took me up in his arms and pressed against my lips a silver image which he wore on his naked breast. I remember that my mother was angry about this, for it was something Catholic, she said, but I liked the image and the foreign soldier who danced around with me, kissed me and wept. He must have had children of his own at home in Spain. I saw one of his comrades led off to execution for having killed a Frenchman. Many years afterwards, at the memory of this, I wrote my little poem, The Soldier, which has been translated into German by Chamisso and become popular there and has been included in the German Soldiers’ Songs as an original German song.

Just as vivid as the impression made on me by the Spaniards when I was three years old was that of a later event in my sixth year, that is to say the great comet of 1811. My mother had told me that it would destroy the earth, or that other dreadful things threatened us which we could read about in The Sybilla’s Prophecies. I listened to everything foretold by superstitious tongues in the neighbourhood and held it in reverence just like some profound religious truth. With my mother and some of the neighbours I stood in the square in front of St. Canute’s Church and saw what we were all dreading so much, the mighty ball of fire with its great shining tail. Everyone was talking about the evil omen and the Day of Judgement. My father joined us, but he was by no means of the same opinion as the others and gave what must have been a correct and sound explanation; but my mother sighed, and the neighbours shook their heads; my father laughed and went away. I was terribly frightened because he did not believe the same as we did. In the evening my mother and my old grandmother talked about it; I do not know how she explained it, but I sat on her lap, looked up into her mild eyes and every moment expected the comet to strike and the Day of Judgement to arrive.

My grandmother came to my parents’ house every day even if only for a few moments; it was especially to see her little grandson, Hans Christian, for I was her pride and joy. She was a quiet and most lovable old lady with gentle blue eyes and a fine figure. Life had been a severe trial for her; from having been the wife of a wealthy countryman she had now fallen into great poverty, and lived together with her feeble-minded husband in a small house they had bought with the last, poor remains of their fortune. I never saw her shed a tear; but all the more profound was the impression she made on me when she quietly sighed and told me of her mother’s mother, that she had been a noble lady in a big German town called Cassel and married what she called a “comedy-player” and run away from her parents and her home, for all of which the generation following her had to suffer. I cannot recollect ever hearing her mention her maternal grandmother’s family name, but her own maiden name was Nommesen. She was employed to look after the garden belonging to the hospital, and every Saturday evening she brought us some flowers which they allowed her to take home with her. These flowers adorned my mother’s chest of drawers, but they were my flowers, and I was allowed to put them in the vase. What pleasure this gave me. She brought everything to me; she loved me from the bottom of her heart; I knew this and I understood it.

Twice a year she burned the green rubbish from the garden. It was burned to ashes in a big furnace in the hospital, and on those days I spent most of my time with her and lay on the great heaps of green leaves and pea-plants. I had flowers to play with, and – something which I specially appreciated – was given better food than I could expect at home. All the harmless mental patients were allowed to walk about in the hospital courtyard, and they often came to look at us. I listened to their singing and chatter with a mixture of curiosity and fear. I would often even go a little way with them to the pleasance, under the trees; indeed when the attendants were present I even dared to go into the building where the dangerous lunatics were kept. There was a long corridor between the cells; one day I crouched down and peeped through the crack in the door, and inside I could see a naked woman sitting on a pile of straw and singing in a most beautiful voice; her hair hung right down over her shoulders. Suddenly she sprang up and with a cry threw herself against the door where I was lying; the attendant had gone away, and I was all alone; she struck the door so violently that the little grating through which food was passed in to her flew open; she saw me through it and stretched one of her arms out after me. I screamed in terror and pressed myself flat against the floor. Even as a grown man I cannot rid myself of this sight and this impression. I felt the tips of her fingers touching my clothes and was half dead when the attendant came back.

Close beside the place where the leaves were burned there was a spinning room for poor old women. I often went there and was soon a favourite of theirs, for when I was with these people I spoke with an eloquence which, they said, indicated that “such a clever child could not live long”, a suggestion which greatly flattered me. I happened to have heard of doctors’ knowledge of the inner structure of the human body, of the heart, lungs and intestines, and that was sufficient for me to give an impromptu talk to the old women. I boldly drew a large number of flourishes on the door to represent the intestines; I talked about the heart and the kidneys, and everything I said made a deep impression on the assembly. I was considered a remarkably clever child, and they rewarded my chatter by telling me fairy tales; a world as rich as that in the Arabian Nights was revealed to me. The stories these old women told me and the figures of the mental patients I saw around me in the hospital all made such an impression on me, superstitious as I was, that when it grew dark I scarcely dared go out of my parents’ house. So I was usually allowed to go to bed at sunset – not on my own settle, for it was too early to get it ready as it took up too much room in our little parlour – but I was put in my parents’ big bed, where the flowered calico curtains hung close around me. I could see the light burning and hear everything going on in the room, and yet I was so much alone in my thoughts and my dreams that it almost seemed as though the real world did not exist. “He’s lying there so nice and quiet, the dear little thing,” my mother would say. “He’s well out of the way and can’t come to any harm.”

I was very much afraid of my weak-minded grandfather. He had only ever spoken to me once, and then he had called me “Sir”, a form of address to which I was not accustomed. He used to cut curious figures in wood, men with the heads of animals, and animals with wings, and strange birds; he would pack them all in a basket and go out into the countryside with them and was everywhere well received by the peasant women; indeed they even gave him oatmeal and ham to take home because he gave them and their children these curious playthings. One day when he returned to Odense I heard the boys in the street shouting after him. Horrified, I hid behind a flight of steps while they rushed by, for I knew I was of the same flesh and blood as he.

I only very rarely played with the other boys; even in school I took no part in their games but remained sitting indoors. At home I had plenty of toys which my father had made for me; I had pictures which could be changed by pulling a string and a treadmill that made the miller dance around when it was set in motion; I had magic lanterns and a lot of amusing knick-knacks. In addition, I took great delight in sewing doll’s clothes or in sitting in the yard by our solitary gooseberry bush and stretching my mother’s apron from the wall with the help of a broom-handle. That was my tent both in sunshine and pouring rain. There I sat and gazed at the leaves on the gooseberry bush and followed their progress from day to day, from their being tiny, green buds until they fell off as big, yellow leaves. I was a singularly dreamy child and usually walked about with my eyes shut, so that at last I gave the impression of not being able to see well, although my sight was, and still is, unusually good.

An old teacher who ran a dame school taught me the alphabet and how to spell and read properly. She used to sit in a high-backed armchair near the clock where some small, moving figures appeared when it struck the hour. She always had a big rod with her, and she made use of it in the class which consisted mostly of girls. It was the custom in the school for us all to spell out aloud, as noisily as possible. The teacher didn’t dare to strike me, as my mother had made it a condition of my going there that I should not be hit; so one day when I was given a tap with the rod together with the others I immediately got up and without further ado went home to my mother, demanding to be sent to another school. And I had my way. My mother put me in Mr. Carstens’ school for boys. There was also one girl there. She was quite small and although she was a little older than I, we became good friends; she used to talk about useful and practical things and of going into service with a good family. And she said that she was going to school especially to learn to be good at sums, because then, her mother said, she would be able to become a dairy-maid in some big manor. “Then you must come to my castle when I am a nobleman,” I said, and she laughed at me and told me I was only a poor boy. One day I had drawn something which I called my castle and I assured her on that occasion that I was a child of high birth who had been taken from his parents, and that God’s angels came and spoke to me. I wanted to impress her like the old women over in the hospital, but she did not take it in the same way as they did; she gave me a strange look and said to one of the other boys standing nearby, “He’s mad like his grandfather!”, words that made me shudder. I had said that in order to make myself look important, but the only effect of what I said was that they thought I was as insane as my grandfather. I never again spoke to her of such things, but we were no longer the same playmates as before. I was the smallest in the school, so when the other boys were playing Mr. Carstens always held my hand in case I should be knocked over. He was fond of me and gave me cakes and flowers and patted me on my cheek, and one day when one of the bigger boys hadn’t learnt his lesson and so as a punishment was placed, book in hand, on the table around which we were seated I was quite inconsolable, and so the sinner was pardoned. Later in life this dear old teacher became the manager of the telegraph station at Thorseng; he was still alive there a few years ago, and I have been told that, when showing visitors around, the old man told them with a delighted smile, “Do you know, you will probably not believe me when I tell you that such a poor, old man as I was the first teacher for one of our most famous poets. Hans Christian Andersen used to go to my school.”

During the harvest season my mother sometimes went out into the fields to glean. I went with her and felt like Ruth in the Bible, gleaning in Boaz’s fertile fields. One day we had gone to a place where there was known to be an ill-natured bailiff. We saw him coming with a dreadful big whip in his hand, and my mother and all the others ran away. I had wooden clogs on my bare feet, and in my haste I lost them. The stubble pricked my feet and so I could not run away quickly enough, and was left behind alone. He caught up with me and had already raised his whip; I stared him in the face and without thinking said, “How dare you strike me when God can see it!” And immediately the stern man became quite gentle; he patted my cheek, asked me my name and gave me some money. When I showed this to my mother she looked at the others and said,

“My Hans Christian’s a strange child. Everyone’s kind to him, and even this bad fellow has given him money.”

I grew up pious and superstitious. I had not the faintest idea what it was to lack anything. I know my parents lived from hand to mouth, as the saying goes, but for me they had everything in abundance. As far as my dress was concerned I could even be said to be smart. An old woman altered my father’s clothes to fit me; three or four big pieces of silk which my mother owned were pinned in turn on my breast and served as waistcoats; a large kerchief was tied round my neck with a huge bow, my head was washed with soap and my hair combed over to the sides, and then I was in all my finery. Thus dressed I went to the theatre for the first time with my parents. Even at that time Odense had a well-built theatre which, I believe, had been started for either Count Trampe’s or Count Hahn’s troupe; the first performances I attended were in German. The director was called Franck, and he put on operas and comedies. Das Donauweibchen was the town’s favourite; but the first performance I saw was Holberg’s The Political Tinker arranged as an opera. I have not since been able to discover who wrote the music, but it is quite certain that this text had been arranged in German as an opera. The first impression otherwise that the theatre and the assembled crowd made on me was not, as might be expected, to make me believe I was a future poet. As my parents later told me, my first exclamation on seeing the theatre and so many people was, “Now if we only had as many casks of butter as there are people here, what a lot of butter I would eat!” It was, however, not long before the theatre became the place I liked best, though I could only go there very occasionally each winter. I made friends with Peter Junker, the man who took the posters out, and every day he gave me a poster, while I, in return, dutifully distributed a few others in my part of town. Even if I could not go to the theatre I could sit in a corner at home with the poster, and according to the name of the play and the characters in it I could make up a whole comedy for myself. That was my first, unconscious literary work.

It was not only plays and stories my father liked reading, but historical works and the Bible as well. He pondered in silence on what he had read, but my mother did not understand him when he talked to her about it, and so he became more and more taciturn. One day he closed the Bible with the words, “Christ was a man like us, but he was an unusual man.” My mother was horrified by these words and burst into tears, and in my fright I prayed to God that He would forgive my father for this dreadful blasphemy.

“There is no other Devil than the one we have in our own hearts,” I heard my father say once, and I was filled with concern for him and his soul. So one morning when my father found three scratches on his arm, which had probably been caused by a nail in the bed, I was completely of my mother’s and the neighbours’ opinion that it was the Devil who had been there during the night to prove his existence. My father had but few friends, and he liked best to spend his leisure hours alone or out in the woods with me. It was his dearest wish to live out in the country, and now it happened that one of the manor houses on Funen urgently required a shoemaker who would settle down in the village nearby, where he would have a house free of rent, a small garden and grazing for a cow; with all this and regular work from the manor he would be able to manage nicely. My mother and father could talk of little other than how happy they would be if they could get this place, and my father was given a piece of work as a test. He was sent a piece of silk from the manor house and was to sew a pair of dancing shoes, providing the leather himself. We talked and thought of nothing else for a couple of days; I so looked forward to the little garden we were to have with flowers and shrubs where I would be able to sit in the sunshine and listen to the cuckoo. I prayed to God so fervently that He would fulfil our wishes; He could bestow no greater happiness upon us. At last the shoes were ready; at home we looked solemnly at them, for they were to decide our future. Father wrapped them in his handkerchief and went off. We sat and waited for him to come home radiant with joy, but when he came he was pale and angry. Her ladyship, he said, had not even tried the shoes on, but had merely given them a sour look and said that the silk was ruined and that she could not engage him. “If you have wasted your silk,” my father said, “then I will be content to waste my leather!” at which he had taken out his knife and cut the soles off. So our hopes of living in the country came to nothing. We wept, all three of us, and I thought that God could easily have granted our prayers. Had he done so, I would have been a peasant and all my future very different from what it has been; since that time I have often wondered whether it was for the sake of my future that our Lord denied my parents their happiness.

My father’s rambles in the woods became more frequent and he knew no rest. The events of the war in Germany, which he eagerly followed in the newspapers, completely occupied his thoughts. Napoleon was his hero, and he thought his rise from obscurity was the finest example to follow. Denmark made an alliance with France. People talked of nothing but war, and my father volunteered as a soldier in the hope of coming home as a lieutenant. My mother wept and the neighbours shrugged their shoulders and said it was madness for him to go out and get himself shot when there was no need for it. At that time soldiers were considered pariahs, and only in more recent times, during the war against the rebels in the Duchies havewe given them the honour they deserve; they are the right arm which wields the sword.

The morning on which the company my father was in was due to march off I heard him singing and talking merrily, but at heart he was deeply agitated. I could see this from the passionate way in which he kissed me good-bye. I lay in bed with measles and was alone in the room when the drums beat and my mother, in tears, accompanied him as far as the city gate. When they had gone my old grandmother came in and looked at me with her mild eyes and said it would be a good thing if I could die now, but that God’s will was always best. That was one of the first really sad mornings I can remember.

However, the regiment to which my father belonged came no further than Holstein. Peace was concluded and the volunteer soldier was soon sitting in his workshop again, and everything seemed to be as usual once more.

I played with my puppets and acted comedies, always in German, for it was only in this language I had seen them acted. But my German was a sort of gibberish which I made up as I went along and in which there only occurred one single real German word, Besen, a word I had picked up from the various expressions my father had come home with from Holstein. “You’ve certainly had some benefit from my travels,” he said in fun. “Goodness knows whether you will ever travel so far afield. But you must. Remember that, Hans Christian.” But my mother said that as long as she had any say in this matter I should remain at home and not ruin my health as he had done.

His good health had been ruined; it had suffered from the marching and the soldier’s life, to which he was not accustomed. One morning he awoke in a state of delirium, talking of campaigns and Napoleon. He fancied he was taking orders from him and that he was in command himself. My mother immediately sent me to fetch help, but not from the doctor; oh no, I was to go to a so-called “wise woman” who lived a couple of miles from Odense. I arrived at her house, and the woman asked me several questions. Then she took a woollen thread and measured my arm, made strange signs over me and finally laid a green twig on my breast; she said it was the same sort of tree as that on which Christ had been crucified, adding, “Now go home along the river bank. And if your father is going to die, you’ll meet his ghost.”

My terror can well be imagined, full of superstition and dominated entirely by my imagination as I was. “But you’ve not met anything, have you?” inquired my mother when I came home. “No,” I assured her with beating heart. On the third evening my father died. His body was left on the bed, and I slept on the floor with my mother; and a cricket chirped throughout the night. “He is dead already,” my mother called to it. “You needn’t call him; the Ice Maiden has taken him,” and I understood what she meant. I remembered the previous winter when our windows were frozen over; my father had shown us a figure on one of the panes like that of a maiden stretching out both her arms. “She must have come to fetch me,” he said in fun. And now, as he lay dead on the bed, my mother remembered this, and his words occupied my thoughts.

He was buried in St. Knud’s churchyard, outside the door on the left as you come from the altar. My grandmother planted roses on his grave. In later years other bodies have been buried in the same place, and now the grass grows high over these too.

After my father’s death I was as good as left to my own devices; my mother went out washing and I would sit alone at home with the little theatre my father had made for me. I would make clothes for my puppets and read plays. I am told that I was tall and lanky at that time; my hair was fair and very thick and I always went bareheaded and wore wooden clogs on my feet.

Not far from my home a parson’s widow, Mrs. Bunkeflod, lived together with her late husband’s sister. They let me go and visit them when I wanted, and as they took a liking to me I spent most of my days there. This was the first house belonging to the educated classes where I found a home. The late clergyman had written poems and had at that time something of a name in Danish literature; everyone knew his spinning songs, and in my Vignettes to Danish Poets I wrote the following words of a man whom my contemporaries had forgotten:

Breaks the thread, the wheel stands still,

Spinning-songs are silent last.

Songs of youth soon vanish will

In the distant, far-off past.

This was where I first heard the word “poet”, and it was spoken with such reverence as though it were something sacred. My father had read Holberg’s comedies for me, but it was not of these they spoke, but of verse, of poetry. “My brother, the poet,” said Bunkeflod’s elderly sister with sparkling eyes. From her I learned that a poet’s calling is a glorious thing, a happy thing. Here, too, I read Shakespeare for the first time, admittedly in a bad translation, but the bold descriptions, violent incidents, witches and ghosts were just to my taste. I immediately began to perform the Shakespearean tragedies in my puppet theatre, and to my imagination the ghost in Hamlet and the mad King Lear on the heath were living figures. The more deaths there were in a play, the more interesting I thought it. It was about now I wrote my first play; it was nothing less than a tragedy in which, of course, everyone died. I had borrowed the story from an old song about Pyramus and Thisbe, but had extended the action by adding a hermit and his son, who both loved Thisbe and took their own lives when she died. Most of the hermit’s speeches were quotations from the Bible and passages from Bishop Balle’s Short Catechism, especially the ones about our duty towards our neighbours. I called the play Abor and Elvira. You mean it should be called ‘A Bore and a Pain’, said our neighbour wittily when I visited her with it after reading it with great pleasure and satisfaction to everyone else I could think of. This put a complete damper on my spirits because I felt that she was making fun both of me and my play, while everyone else had praised it. Much upset, I told my mother what had happened. “She only says that because it’s not her son who’s written it,” she said. And I was consoled and began on a new play which was to be in a more pompous style; a king and a princess were to appear in it. Of course I could see that such people in Shakespeare’s plays talked like other men and women, but it did not seem to me to be quite right that they should do so. I asked my mother and several people in the neighbourhood how a king really spoke, but no one knew for sure. They said it was many years since a king had visited Odense, but that he probably spoke a foreign language. So I found myself a sort of dictionary in which there were German, French and English words with Danish translations, and this helped me. I took a few words from each language and fitted them into each sentence spoken by my king or my princess. “Guten Morgen, mon père; har De godt sleeping” was one of the lines; it was really and truly the language of Babel, and that, I considered, was the only suitable way for such elevated personages to speak. Everyone had to listen to my play, and it gave me a profound joy to read it aloud. It never occurred to me that it could be anything but a pleasure for everyone else to listen to it.

Our neighbour’s son had been set to work in a cloth-mill, whereby he earned a small sum every week. On the other hand, according to what people said, I just hung around doing nothing at all, so my mother decided that I, too, should go and work in the mill. “It’s not for the sake of the money,” she said, “but so I know where he is.”

My old grandmother took me there and was deeply distressed, for, she said, she had never thought to see the day when I should mix with all those wretched boys.

Many of the journeymen working there were German; they sang and talked merrily together, and many a coarse joke of theirs caused great amusement. I listened to it and have learned from that that a child can listen to such things with an innocent ear, for it did not reach my heart. In those days I had a remarkably beautiful and high-pitched soprano voice which I retained until my fifteenth year; I knew people liked to hear me sing, and when I was asked in the mill whether I knew any songs I immediately began to sing, and did so with great success; it was left to the other boys to do my work. When I had finished my song I told them that I could also perform plays; I knew whole scenes of Holberg and Shakespeare off by heart, and I recited them. Both men and women nodded amicably to me and laughed and clapped their hands. In this way I found the first days in the mill extremely cheerful. But one day, just as I was singing to them and everyone was talking about the clarity and remarkable pitch of my voice, one of the journeymen exclaimed, “That can’t be a boy; it’s a little girl!” He took hold of me. I cried out and screamed, but the other journeymen found the coarse joke amusing and held my arms and legs fast. I screamed at the top of my voice, and, as bashful as a girl, I rushed out of the mill and home to my mother, who immediately promised me that I should never go there again.

I started visiting Mrs. Bunkeflod again. I listened to her reading aloud, did a lot of reading myself and even learnt to sew, a skill I found necessary for my puppet theatre. And I sewed a white pin cushion as a birthday present for Mrs. Bunkeflod. As a grown man I have noticed that this pincushion has been preserved. I also made the acquaintance of another clergyman’s widow in the neighbourhood, and she allowed me to read aloud to her from books she borrowed from the lending library. One of them began roughly as follows: “It was a tempestuous night, and the rain was beating against the window panes.” “That’s going to be a lovely book,” she said, and I innocently asked how she knew. “I can tell from the beginning,” she said. “It’s going to be excellent.” I looked up to this very clever woman with a kind of reverence.

Once during the harvest my mother took me with her from Odense to a mansion near her native town of Bogense. The lady of the house, for whose parents my mother had once worked, had said that we must come and visit her some time. I had been looking forward to this for years, and it was going to happen. It took us a whole two days to get there, for we had to go on foot. It was a lovely house, and we were given delicious food to eat, but apart from this the countryside itself made such an impression on me that all I wanted was to remain there for ever. It was in the hop-picking season, and over in the barn I sat together with my mother and a whole lot of peasant folk and helped to pick the hops. They told stories and talked about all the wonderful things they had experienced and seen. They knew all sorts about such things as the Devil with his cloven hoof, ghosts and signs. There was an old peasant among them who said that God knew everything, both what had happened and what was going to happen. These words made a deep impression on me; they constantly occupied my thoughts, and towards evening, as I was walking alone some distance from the house, I came to a deep pond. I crawled out on to one of the big stones in the water, and in some strange way the thought entered my mind as to whether God really knew everything that was to happen. “Well, He’s decided now that I’m going to live to be a very old man,” I thought, “but if I jump out into the water and drown myself things won’t turn out quite as He wants them to.” And all at once I was firmly and resolutely determined to drown myself. I turned towards the spot where the water was deepest – and then a new thought went through my head: “It’s the Devil who wants me in his power!” And I cried out, ran home as quickly as I could and, weeping bitterly, flung myself, into my mother’s arms. But neither she nor anyone else could persuade me to say what was the matter. “He must have seen a ghost of some kind,” said one of the women, and I almost thought so myself.

My mother married again, and her second husband was also a young shoemaker. His family, too, were artisans, but they thought he had married below himself, and neither my mother nor I was permitted to visit them. My stepfather was a quiet young man with lively, brown eyes and was reasonably good-tempered. He said he wouldn’t interfere in my education, and he did indeed allow me to follow my own interests. So I lived entirely for my pictures and my puppet theatre. And it was my greatest delight that I had collected a considerable number of pieces of coloured cloth which I cut out myself and made into costumes. My mother regarded this as good practice for me if I were to become a tailor, and that, she believed, was what I was born to be. I, on the other hand, said I wanted to go on the stage, something my mother firmly opposed, for the only actors she knew of were tight-rope walkers and strolling players, and these she classed as one and the same thing. “Then you can be sure you will get some good beatings,” she said. “And you’ll be starved to make you light, and you’ll be given oil to drink to make your limbs supple.” No, I was to be a tailor. “Just see what a fine position Mr. Stegmann has.” He was the best tailor in town. “He lives in Korsgade, and look what big windows there are in his shop, and there are assistants sitting on the table. Oh, if only you could become one of them.”

The only consolation I could find in the prospect of becoming a tailor was that then I should really be able to get a lot of odd bits of cloth for my theatre wardrobe.

My parents had moved further up the street to a house just by the Monkmill Gate, and there we had a garden; it was very small and narrow, and was actually no more than a long bed with red currant and gooseberry bushes in it, and then the path which led down to the river behind the Monkmill. Three great waterwheels turned beneath the fast flowing water and stopped suddenly when the sluice-gates were closed. Then all the water ran from the river; the bed dried up and the fish splashed about in the pools that were left, so that I could catch them with my hands; and under the great waterwheels fat water-rats came out from the mill to drink. Suddenly the sluicegates were raised again; the water rushed down again, foaming and roaring, the rats were no longer to be seen, the river bed filled up, and I, who had been standing out there, splashed back through the water to the bank as fast as I could. I was just as frightened as ambergatherers on the North Sea coast when they are a long way out and the tide turns. I used to stand on one of the big stones my mother used as a scrubbing board and sing all the songs I knew at the top of my voice. There was often neither sense nor tune in them, just what I made up as I went along. The garden next to ours belonged to a Mr. Falbe, whose wife Oehlenschläger mentions in his autobiography. She had been an actress and had looked beautiful as Ida Münster in the drama Herman von Unna; she was known as Miss Beck in those days. I knew that when they had company in the garden they always listened to my singing. Everyone told me that I had a beautiful voice and that I should be able to make a name for myself with it. I often wondered how this name would come, and as I saw the sort of thing that happens in fairy tales as the truth, I expected all kinds of wonderful things to happen. I had been told by an old woman who washed her clothes in the river that the Empire of China was right under Odense River, and I didn’t think it was by any means impossible that a Chinese prince, one moonlit night as I was sitting there, might dig his way up through the earth to us, hear me singing and take me down to his kingdom with him and there make me rich and give me a high position. But then, of course, he would allow me to go and visit Odense, where I would live and build a castle. I could sit for evening after evening drawing and planning it. I was simply a child, and so I was, long afterwards, when I appeared in Copenhagen and read my poems. I still believed and expected to find some prince in my audience, and that he would understand me and help me. But it was not to happen in this way – though it was to happen.

My passion for reading, the many dramatic scenes I knew by heart and my extremely fine voice all attracted the attention of several distinguished families in Odense. I was invited to their houses, and all my remarkable characteristics awoke their interest. Of the many people I visited, Colonel Høegh-Guldberg was the one who, together with his family, showed me the most genuine interest. Indeed he even spoke of me to Prince Christian, subsequently King Christian the Eighth, who at that time was residing in Odense Castle, and one day Guldberg took me there with him.