9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

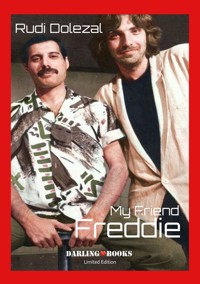

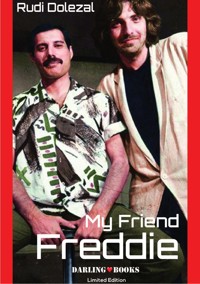

Cult director Rudi Dolezal, awarded at the Grammys for his film "Freddie Mercury - The Untold Story", has won numerous international film, music and TV awards and has filmed stars from all over the world: The Rolling Stones, Whitney Houston, Lionel Richie, Bruce Springsteen, Michael Jackson, Falco, and many more. From the very beginning, Dolezal had a very special relationship with Freddie Mercury and Queen, for whom he directed a total of 32 music videos. In his book "My Friend Freddie" Rudi Dolezal tells stories he has never told before. He guides the reader from beginning to end, starting with the unusual start of a friendship that was to last a lifetime. He talks about many private moments, including the last time Freddie stood in front of a camera. In front of his camera.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

My Friend Freddie

by

Rudi Dolezal

DARLING BOOKS

Limited Edition

© 2022 Archive Productions LLC

Author: Rudi Dolezal

www.myfriendfreddie.com

Publishing label: Darling Books

ISBN Softcover: 978-3-347-71741-1

ISBN E-Book: 978-3-347-71748-0

Translation from German: Christine Hohlbaum (www.hohlbaum-pr.com)

Print and distribution on behalf of the author:

tredition GmbH, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany

The work, including its parts, is protected by copyright. The author is responsible for the contents. Any reproduction is not permitted without the author’s written consent. Publication and distribution are carried out on behalf of the author, who can be contacted at: tredition GmbH, Dept. “Impressumservice,” Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg, Germany. Deutschland.

For Ruby and Benny – The sunshine of my life.

Table of Contents

A Preface of Sorts

How Do You Get to Be the Video Director for Queen and Freddie Mercury?

A Dream Come True:Directing the Video “One Vision”

Freddie, The Philosopher (“One Vision” Re-Shoot)

Freddie’s Birthday Party in Munich –Filming “The Black And White Party” –“Living On My Own”

The World’s Dumbest Club Owner

Freddie’s Teeth

How the Idea for “Magic Years” Was Born

“What Are You Doing Next Week?” –

“Friends Will Be Friends”

The “Inner Circle”

Crazy Hat Party –

Freddie Makes the Bed for Me and Suzie

“Teeth, Hair & Nose” – Freddie’s Super Group with Rod Stewart and Elton John

“The Invisible Man” – On All Fours with Freddie – Cocaine Under the Table

Four Against Willi – Barbara’s Vagina

Queen Throws a Party for Gerry Stickells –Cost Estimate from the Brothell

Video Shoot “Time” – Eleven Gay

Men and I in the “Time Suite”

Freddie on Sex and Love or “May I

Introduce You to My Husband” (Jim Hutton)

Video shoot “Breakthru”– The Tunnel of Doom

Encounters with Mary Austin

“The Miracle” – Four Little Boys Play Queen

Peter Freestone – Girl Friday

“Ping Pong” Between Freddie and Rudi

“Innuendo” – No More Videos With

Freddie … and Yet!

Does Freddie Have AIDS? –

An Evening with Barbara Valentin

Was Elton John the Gorilla?

Finally! – The Gorilla Secret is Revealed

Freddie Mercury’s Kiss

Freddie’s Last Take - The Last Scene of a Superstar in front of the Camera and Why I only Understood after His Death Why He Wanted to Shoot the “Last Take” at all Costs One More Time

The Perfect Illusion: Freddie Mercury and David Bowie Live on Stage Performing “Under Pressure”

Untold Stories about “The Untold Story”

Absolutely Backstage

During the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert

Rudi’s 40th Birthday –

When Queen Played a Concert for Him

When the Dying Began

Thank You, Freddie!

EPILOGUE – Freddie’s Last words

Footnotes

Postscript and Acknowledgements APPENDIX

Films and Videos by Rudi Dolezal for Freddie Mercury & Queen (Selection)

Credits – Photos and Visuals

A Preface of Sorts …

I was never really a fan of Queen, and before I got to know him, certainly not of Freddie Mercury. Back in 1971, It never would have occurred to me that I would one day be allowed to work with one of the greatest bands and one of the most charismatic superstars in rock history. My band has always been the Rolling Stones: filth, dirty, and insolent with that Keith Richards guitar sound that punches below the belt and hotwires your ears to your genitals.

Nevertheless I accepted when, at the beginning of the ‘80s, the record company offered the chance to interview the Queen singer Freddie Mercury in Munich. After all, Queen were then - as they are today - one of the most successful bands in the world. Freddie Mercury’s reputation for hating TV interviews preceded him so I set off for Munich with my TV crew, my palms sweating. Freddie was rumored to be a very difficult interviewee.

How very differently it would turn out.

The interview with him - I still remember it as if it were yesterday - took place in the bar of a farmhouse parlor at the Hilton Tucherpark Hotel in Munich. From the very first moment, the two of us clicked. We were instantly simpatico.

The ice was quickly broken.

This was followed by the - now legendary – “Prostitute Interview” and the trigger for years of collaboration.

I also illustrate it in this book, which really “only” describes my story with Freddie.

In My Friend Freddie, you will not find a complete biography, not Freddie’s exhaustively researched facts and complete history, but my story - the story of a long-haired hippie who set out from the 9th district of Vienna to conquer the world as a video director and music filmmaker. With enough cheek, naivety and chutzpah to tell even a Freddie Mercury after that first interview: “I‘ll send you a copy of my TV segment, and if you ever need a really good video director …” - Freddie nodded politely - “call me!” I handed him my business card. I the long haired hippie added -

OH RUDI …

A few months later, I, a young Austrian filmmaker, was in the studio with Freddie for Queen Productions, directing an official Queen video that was to cause a worldwide sensation.

Wow.

The chutzpah had paid off.

And the naivety had kept me from thinking about the fact that Freddie and Queen had worked exclusively with top English and American directors like David Mallet for their videos until then, and from doubting that this world-famous band was waiting for a hippie from Vienna’s Alsergrund, of all places. But Freddie’s look at the end of the first interview in that farmhouse parlor at Tucherpark in Munich somehow signaled to me, “Go for the impossible, Rudi!”

The relationship between Freddie and me was to become a very special one over the years. Not only did he make me his “personal filmmaker,” so to speak for years, but we also became friends. As a friend, writing a book about my friend is not easy.

It has taken me more than 25 years.

I tell stories in this book that I’ve never told before. What went on behind the scenes of video shoots, how I traveled halfway around the world with and for Freddie, from London to New York, from India to Rio de Janeiro, from Zanzibar to Montreux … Freddie on Tour, Freddie in private, Freddie the prankster, Freddie the patron … Freddie at the very last interview he ever gave in front of a camera - in front of my camera.

And just as I remember the first interview with him, I also remember the dreadful phone call from his manager, Jim Beach, when he told me that Freddie had passed.

Although - for me, Freddie is still there. Omnipresent. Present. Not only in his songs and in my countless videos (many of them with my longtime partner Rossacher), picture documents, documentaries, interviews … No. Freddie was, next to Frank Zappa and Keith Richards, my best advisor, mentor, encourager.

I feel him to this day in important projects when he says: “Never try to be second best.” I have him in my ear as an admonisher before I would make a mistake when he says, “This is too clever, Rudi!” …

And at the same time, I miss him. I miss him so much. Every day. His wit, his intelligence, his radicalism, his understanding of art, his excess.

Forgive me, dear reader, if this book has also become a bit of a coping mechanism to manage the loss of a friend.

And as Freddie would say: “Now, get on with it, Rudi, I’m getting bored!”

I hope you enjoy reading my stories about one of the most extraordinary people I have ever had the privilege to meet.

This is for you, Fred.

CHAPTER 1

How Do You Get to Be the Video Director for Queen and Freddie Mercury?

People often ask me how it came about that Dolezal would come to work for Queen. Whatever they hoped to hear, I would always disappoint them. Because it was neither a big plan (and if it was, then not by me) nor a successful coup. It wasn’t a clever, strategic stealth mapping out of things, it wasn’t tireless networking, it wasn’t endless ambushes, it wasn’t meddlesome nagging. The key was an inconspicuous little phrase that has had an enormous impact on my entire life: “Stick with it”; just stick with it. To the things you want to achieve, and in general: to life itself.

Back then, in the early ’80s, I worked for Austrian television: For those who can still remember, the program was called “Ohne Maulkorb” (“Unmuzzled”)*1). Those who don’t, may imagine it exactly as it sounds: We were a young editorial team who couldn’t keep our mouths shut. And, of course, it was a lot about music too.

At some point, we had a story coming up in Munich. Christine Feldhütter (back then her name was Christl Hruska), the promotion lady for the record label EMI, said the band Queen was in town and available for an interview. It was a relatively insignificant TV report about the very significant band Queen. So it definitely sounded interesting. Since “Ohne Maulkorb” was the only program in Austria at the time that dealt with pop music on TV, I did two to four interviews with pop stars a month. Either I or my later partner Hannes Rossacher did the music segment. I got Queen.

Not too much was promised by the management in advance. There was a photo session to film (yawn), two interviews - one with Queen guitarist Brian May (interesting), one with Freddie Mercury (very interesting) - and a press conference (yawn). I agreed. The two “yawn” items on the agenda made me a bit nervous. First of all, bland photo sessions and dull press talks are truly no cinematic test of maturity, and secondly, such boring events rarely turn into gripping scenes. So I had to make up for that with the interviews. With correspondingly mixed feelings and a modest film crew consisting of one cameraman and a sound technician, I boarded our tiny bus to Munich.

It was as I had feared. The photo session was filmed near the in-location P1 at Prinzregentenstraße 1 and lasted less than five minutes. The press conference took place inside P1 and was similarly disappointing. The only surprise was Barbara Valentin, unknown to me at the time, who posed on the sidelines of the press conference. For the interviews with Freddie and Brian, we moved to the Hilton at Tucherpark, a hotel that was to become my new home in the years to come. But, of course, I didn’t have a clue about that at that time.

Brian May was very polite, precise and frankly not very exciting. Later, when we knew each other much better, I once told him that I appreciated it when people answered my questions as honestly and in detail as he did, purely as a human being.

But as an interviewer and director, I’d rather he made up a story here and there that was more exciting.

Freddie Mercury was a very different story. I entered the brown, wood-paneled room with a rustic design. I think it was a bar. Packed with an entourage of assistants, press managers, a makeup artist and someone I didn‘t know at the time who introduced himself as a producer named Mack. Freddie stood somewhere in the middle. He was consuming a transparent drink, which I mistook for water. Later I realized it must have been vodka. Freddie loved vodka. It was five in the afternoon, and I was the last interview of what had been a very long and tiring media day for Freddie. He was wearing a white undershirt and jeans, and we hit it off right from the start. It was just the interview that made up for the boring parts for my film!

Freddie took a sip from his glass and turned to me. “I’ve had to do crap interviews all day today,” he said. “You’re the last person I’m talking to, and because I’m glad it’s almost over, you get the best interview, darling!” And he was true to his word, delivering meaty soundbites like: “I’m just a musical prostitute, my dear” or, “If people ever stop buying our records, I’ll become a strip artist or something.”

I dug deeper, “What music would you strip to?” Freddie cast me a prankster’s grin and replied, “To mine.” He tilted his head. “To all the songs I’ve written – that’s why I wrote them!” He burst out laughing - a laugh with which I would become so familiar. Once he had calmed down, he added, as if we’d known each other forever, “You believe that, you’ll believe anything!”

The ice was broken.

The story was in the can so we packed up the cameras.

The young hippie Dolezal from the 9th district of Vienna, around the time he shot the “Prostitute Interview” with Freddie

We said goodbye, and I promised to send a copy of it to London as soon as it was finished. You must remember that it was the time of VHS cassettes, something you can hardly imagine today. Anyway, all the artists heard such phrases from all the television editors, but no one stuck to them. Ninety-nine out of a hundred TV journalists never bothered to actually pull a copy, put it in an envelope, write an address on it, and carry it to the post office … I was the hundredth. I wanted more. Freddie and I had really hit it off, and I imagined I felt a chemistry between us. During that little TV segment for “Ohne Maulkorb,” I realized that Freddie and I were on the same wavelength. Stick with it, Dolezal!

I beg of you!

The likelihood of being hired by Queen for a directing job back then as an Austrian was about as great as it was for North Korea to become soccer world champions in 1985. I gave it a try anyway. I had a VHS tape made of my segment, sat down and meticulously labeled the label myself and dashed it off on a travel typewriter, laboriously using my two-finger system. When I had finally typed in the name, address and, very importantly, the telephone number (it was still the time of landlines), I sent the package to London, to Queen’s management.

So far, so good.

A little while later, Jim Beach, Queen’s manager, called me.

“Am I speaking to Rudi Dolezal?”

“Yes, speaking.”

Jim cleared his throat.

“You sent us this little package with a cassette of the Queen piece you shot in Munich, including the interviews with Freddie and Brian. We liked it quite a lot.”

“I’m glad.”

“Do you work exclusively for Austrian television or also as a freelancer?”

Jim Beach became a fatherly friend in the course of our collaboration and has remained so to this day, but back then it took me a while to really register who was on the line. And I didn’t understand what he meant at all at first. Before I could answer, Jim continued. He wanted to know if I wanted to come to Munich as I was on the shortlist of directors to shoot the new Queen video.

The phone almost fell out of my hand. I had taken the call in passing … in a split second I had forgotten where I was actually going. I let myself sink into an armchair. The world-famous, big band Queen called little Rudi Dolezal about a video. Queen, who could hire the best and most famous directors in the world, mostly from England or the U.S., with a snap of their fingers, contacted me in my bachelor apartment in Vienna’s sixteenth district because they might want to work with me!

“Yes,” I said. “Gladly. I am on my way.”

Then I booked the next flight to Munich. I would have crawled there on all fours if I had to.

What just happened?

Later I talked about that call many times with Jim Beach, Freddie and the band. According to what I know today, several things had come together:

Item one and, first and foremost, the VHS tape with the copy of my segment for “Ohne Maulkorb.” “We liked what we saw,” Freddie said later. “You made a lot out of very little. The feature was cleverly put together and, most importantly, very rhythmically edited, and the interviews stood out because your questions weren’t the routine ones. We thought to ourselves, this kid is good.”

But so were many other directors.

Item two on the list of things that came together so well: Queen were the big stars of “Live Aid” that year. “Live Aid,” it should be noted, had been organized by Bob Geldof, who also later became a friend of mine. It was intended to be a worldwide outcry. An appeal for the first fundraising campaign on TV against famine in Ethiopia. For this he had enlisted the biggest pop stars in the world. At the same time, huge concerts were held at Wembley Stadium in London and John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, featuring a lineup of stars that had never before been seen on one stage together, let alone on television. Among them were David Bowie, Elton John, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Dire Straits, Sting, Santana, Madonna, Status Quo, Tina Turner, Eric Clapton, Phil Collins, U2, Black Sabbath, The Beach Boys, Simple Minds, Sade, Duran Duran, Judas Priest, Bryan Adams and many more. In the aftermath, there were various opinions about how musically valuable this evening might have been. Some critics said that Geldof’s idea of a “jukebox” on television had only worked to a certain extent. The concept, according to which one star band after the other played their hits, had only produced a few highlights, for example the duet by Mick Jagger and David Bowie or the performance by Bob Dylan with Keith Richards and Ron Wood of the Rolling Stones and, of course, Queen. However, there were no divided opinions about one thing: Queen was the best band of the “Live Aid” show. Freddie’s performance is still considered one of the great moments in pop history, yet Queen’s performance lasted less than thirty minutes. But the way he inspired the audience in the stadium and on the TV screens was simply unique. In any case, it was life-saving for many starving people in Africa. The appeal for donations reached one billion people worldwide, the estimated “Live Aid” audience. As I learned later, immediately after this triumph the internal discussion with manager Jim Beach took place to use this success also for Queen’s trajectory.

You don’t just let attention like this fizzle out in show business; you’ve got to place something on top. However, there was a stumbling block. Because in reality the four had agreed on a Queen-free time. If I remember correctly, John Deacon had planned a world trip, Brian May a vacation with the family, Roger Taylor a boat trip with friends and Freddie a solo album. In other words, no one really had time for Queen.

Point three, which led me to Jim’s call, was directly related to this and was a purely geographical one. Vienna was close to Munich. And there I had an advocate named Mack. Because time was short, there were only a few days in Munich when all the band members could get together. It was just enough to write a song together, record it and shoot a video at the same time. In the Musicland Studio in Munich. And there sat Mack, that producer from the farmhouse bar in the Hilton at Tucherpark, who by now had seen my Austrian TV reports about people like Frank Zappa, Tom Waits, David Bowie or the Stones and put in a good word for me with Queen. (Thanks, Mack!)

But, as the phone nearly cascaded from my hand in Vienna, I didn’t know any of that yet. All I knew was that Jim Beach had asked me if I could come to Munich.

So I went to Munich for the meeting with the Queen manager, again at the Hilton Munich Park Hotel.

“So,” Jim Beach said. “This is our plan: The entire video is to be shot in the recording studio during the recording session. Now please go down to the restaurant, get your thoughts together, and give me a detailed budget in two hours.”

“Yes,” I said, repeating myself as I did on the phone. “Gladly.”

I went down, sat down at a table in the hotel restaurant. I remember exactly what I was wearing that day. Raunchy jeans with an Indian shirt stuffed into my pants. A briefcase wouldn’t have suited my look or my long hair, not to mention that in my eyes, only business assholes had briefcases like that. An old army shoulder bag with a peace sign was my trademark. At the time, I had never constructed an international budget in English on my own, certainly not without a production manager. It was also the time when there were no computer programs, laptops or iPads, hard to believe. I had paper and pencil and no idea. Not to mention that a budget like this is something that even seasoned professionals can’t pull off in a few minutes at a restaurant. You need a lot of information, quotes, price comparisons, etc. to do this. Seriously, we are talking about two days’ work. I had two hours … And it took me a lot less time because I kept thinking: I hope I’m not too expensive. I hope no competitor is cheaper. I really want to do this Queen video. I would pay to be allowed to shoot a Queen video!

With a budget of about 25,000 DM*2) I dared to go back up to Jim’s room. With the same sweaty palms I had when I first met Freddie, I laid my calculation on the table by the sitting area. Jim took the sheet and studied it. For minutes. It seemed like hours to me.

Shit, I thought, I could have subtracted something else there … there I could have …. And anyway. In my mind, I kept turning over the numbers I had scrawled across the page. Then Jim Beach looked at me and said:

“Okay, you’ve got the job.”

Much later, Jim once confessed to me that he had never in his life received such a cheap budget for so much effort. My good price was the final deciding factor. But what I find charming to this day is that it wasn’t an agent or manager, a great showreel or an expensive brochure that got me my first director’s job with Queen. It was what I had felt from the beginning: a personal chemistry between Freddie and me. And the fact that I had kept my word and sent them the result of my work.

That measly VHS tape with the laboriously typed label had started it all.

CHAPTER 2

A Dream Come True: Directing the Video “One Vision”

Be careful what you wish for …as the saying goes. It might come true! Well, at this point I threw caution to the wind. I had finally landed it, the task of directing an official Queen video. That alone was friggin’ amazing, but I knew in my heart of hearts that it was about more than just a single video. It was a chance of a lifetime, a moment in which I could now present my work to the world. It was 1985. and Queen videos played around the world on every TV station imaginable. In the international music industry at the time, each new clip from the band was immediately eyed with suspicion. After all, Queen were the pioneers of music videos. They had invented the genre with “Bohemian Rhapsody”, so to speak. They had defined it and finally elevated it to new heights. My selfawareness and chutzpah, which I had been able to turn into positive energy to get the job, had given way to doubt and nervousness. Would I be up to the challenge? Had I given myself too much credit? Or worse: Would I even fail at the task? A horrible thought! What’s more, I couldn’t let anyone notice my insecurity. Especially not Jim Beach. Managers can smell doubt a mile away. And I was afraid that he would then quickly call off the deal with DoRo (the name of the film production company Hannes Rossacher and I shared) in order to put a Queen-experienced director like David Mallett on the job. I had to play it cool even though both confidence and doubt did battle in my mind. Sometimes one or the other would get the upper hand. It was a struggle for sure.

I had multiple reasons to be both nervous and under pressure: To film a video in what I saw to be a poorly lit recording studio was a nightmare for a visual person such as myself. Not to mention the fact that I only had a few days to get the job done, which didn’t make things any easier. Plus working with unpredictable world stars can push you to the limit. To make matters worse, I had no chance to really speak with the band ahead of time. We were supposed to first meet Queen on the first day of the shoot and then get started right away. Despite all these circumstances, it was my mission to convince everyone that this would not be the one and only Queen video I ever did. It felt, to say the least, like Mission Impossible.

To put it bluntly: Of course, the mere fact of being hired as the director to shoot a video with Freddie Mercury & Queen was already a sensation and an incredible honor, which at the time, in my youthful cockiness, I was not even remotely aware of to any real extent. Just to be able to write a footnote in the history of Queen, one of the most important bands in the world, was a dream come true. Hippies from the ninth district of Vienna such as myself usually did not even come close to such a chance. Confidence began to take the upper hand once again. After all, I tried to remind myself that I hadn’t just fallen off the turnip truck. Three years earlier I had shot my first video for the Stones, but even working with Mick Jagger, just as with Falco (“Rock Me Amadeus”) or Austrian superstar Ambros, I was used to having at least a preliminary discussion. To sound out what the artist thinks. What he expects. In particular, what he expects from me. In order to be able to produce as precisely as possible. In this case, I had none of that. The video “One Vision” had become a video blind date.

So I had to think my way into Queen in their entirety. That approach granted me a sense of calm and I have to admit I wasn’t too bad at doing that. Then before you knew it, doubt crept up behind me again. Because in this case, thinking wasn’t enough. I had to be a psychic. Acting without really knowing Queen. At this point I had only done one interview each with Freddie and Brian. I hadn’t really seen Roger Taylor and John Deacon at all, except briefly while filming the photo session, but that didn’t count for a production like this one. What made them tick? What might they think was good? What would they expect from me? And anyway, what does the world expect from a Queen video? I had had enough of the constant questions in my mind. I wanted answers instead.

I began to focus on what I knew, which wasn’t much. The location was set: a recording studio, specifically Musicland. That was a fact, period. Because of time constraints, nothing else was an option. A recording studio! Which, as the name suggests, was not built for filming. That limited our creative potential enormously. The only thing worse, I thought, would be to shoot in the dark. At that time, I had already filmed with Wolfgang Ambros, Falco and Georg Danzer in recording studios, but those were pure documentaries. That was something completely different. Besides, it was the time of elaborate, sometimes even surreal video clips as a new art form, the likes of which included Talking Heads with “Road To Nowhere,” Peter Gabriel with “Sledgehammer” or Laurie Anderson with “O Superman”. Having to shoot a demanding video clip in a recording studio, for the whole world at that, was like having to take part in the Tour de France on a tricycle and still wanting to win. It was … crazy!

But fear isn’t enough, I finally thought. Fear is always the worst advisor. Ideas had to come, and quickly. A concept had to be created, if necessary without the artists. I was still nervous as hell, no question about it. On the other hand, I felt in some way that I was up to the challenge. The meeting with Freddie at the first interview still had a lasting effect, as confirmation and encouragement. After I had made my decision, the concept was also quickly clear: I wanted to present Freddie and Queen as no one had ever seen them before - backstage, behind the scenes. The studio was to become a stage, so to speak.

Control Room Musicland Studios: Everything that went on was filmed, even gags that Freddie & Queen did (behind left: Cameraman W. Simon – at the mixing desk, sitting: Director R. Dolezal)

To do this, we (my partner Hannes Rossacher, the cameramen Wolfgang Simon and Peter Röhsler, and I) wanted to light the entire Musicland studio in such a way that we could film Queen in every situation without having to reset the lights each time. We wanted to be able to spontaneously capture authentic situations as they really happened: when the band members were writing lyrics, composing the melody, when they were fooling around or discussing, when they were taking a break, and of course during the recording as a sync performance, i.e. when they were recording the song.

The possibilities were limited, yes. But I had an irrepressible ambition and will to use them and make something extraordinary out of them. I wanted to amaze Queen, surprise Jim Beach, and prove Freddie right, who had implicitly said at the first meeting: You don’t have a chance, but take it! And here’s what I set out to do. Since we were so limited visually, I wanted to start from the music more than any other international video of the time, in terms of editing rhythm and imagery. To be better, more to the point. I saw myself as a musician, my instruments were the camera and my editing rhythm. And I thought about image divisions, so-called split screens for parallel actions. That was the theory.

The shooting itself was to present me with one or two challenges. Musicians, and especially world stars, don’t like to be filmed during the creative process. So I first had to work out a basis of trust with Freddie, Brian, Roger and John together with my team. Apart from my ten-minute TV report from “Ohne Maulkorb,” Queen knew practically nothing about my work as a video director. Yes, they had probably seen “Rock Me Amadeus” with Falco, and Jim had told them that the video was by DoRo. Maybe they also knew my video with the Stones on “Time Is On My Side.” But those clips had no precedent whatsoever for “One Vision.” “Rock Me Amadeus” was staged with actors. “Time Is On My Side” was based on archive footage and a live performance - completely different concepts. In other words, it was not going to be easy.

Of everyone, it was Freddie who made it easy for me. During the shoot, he was approachable, understanding and uncomplicated. I had the feeling he wanted me to succeed. Whenever the others would complain, he reminded the other Queen band members about what we were trying to achieve here, that they should present the unvarnished version of themselves. In other words, backstage. He helped me. He was my partner. He was my ally. At least in terms of the video work itself.

Freddie during the video shoot of “One Vision”: “Fried Chicken!”

Hannes Rossacher and I had an ideal division of labor. I was the communicator, the one who brought all ideas and plans to Freddie and the band and discussed them. Hannes stayed in the background and maintained the overview. The shooting days in Musicland went well at first and then got better and better. We shot a number of interesting scenes, all of which can be seen in the final video: Freddie tweaking lyrics with Roger and Brian in the control room. John practicing his bass theme in the lounge. Brian, playing the pinball machine. Roger dancing around the drums like a St. Vitus dance, or John - to the confusion of the audience - suddenly putting the bass aside and sitting down at the drums to play along perfectly.

Freddie also began to offer more and more hilarious scenes on his own. He acted as if he were exhausted and pretended to sink onto a bench with his bare upper body. In addition, there were unusual creative ideas from us beyond the typical recording studio scenes. For example, the beginning of the song had a strange sound collage that inspired me to do a surreal camera walk down to the studio. The Musicland studio was located in the basement of the Araballa Haus in Munich and could only be reached down a long flight of stairs. It seemed as if you were descending into the underworld. For this, I imagined slow-motion image cross-fades.

Another example was during a Freddie vocal solo in the middle section when we darkened the recording studio. Freddie stood completely still. Wolfgang Simon’s dynamic handheld camera was constantly going three hundred and sixty degrees around him, getting faster and faster as time wore on. It had been Freddie’s idea and would become a cool optical moment in the final video. Later, during a dinner at an Italian restaurant, Freddie had another great idea for this solo part: Queen owned the rights to their legendary live concert at “Rock in Rio” where they had performed in front of more than 300,000 spectators. “Why don’t you take the impressive crowd shots from Rio,” Freddie said after the second grappa, “and blend them over the black as if I’m singing this middle section alone on the one hand, and in front of hundreds of thousands on the other!” Great. The concept grew and grew and grew into a true collaboration Queen & DoRo.