Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A woman searching for her birth-parents unlocks the secrets of her horrific past, as she tries to stop the goblin within in this kaleidoscopic dark psychological horror, with a dread-inducing climax you will never forget. Perfect for fans of Eric LaRocca and Catriona Ward. Myrrh has a goblin inside her, a voice in her head that tells her all the things she's done wrong, that berates her and drags her down. Desperately searching for her birth-parents across dilapidated seaside towns in the South coast of England, she finds herself silenced and cut off at every step. Cayenne is trapped in a loveless marriage, the distance between her and her husband growing further and further each day. Longing for a child, she has visions promising her a baby. As Myrrh's frustrations grow, the goblin in her grows louder and louder, threatening to tear apart the few relationships she holds dear and destroy everything around her. When Cayenne finds her husband growing closer to his daughter, Cayenne's stepdaughter, pushing her further out of his life, she makes a decision that sends her into a terrible spiral. The stories of these women will unlock a past filled with dark secrets, strange connections; all leading to an unforgettable, horrific climax.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 299

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Cayenne

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Myrrh

Marian

Myrrh

Sandra

Cayenne

Sandra

Myrrh

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Marian

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Sandra

Cayenne

Sandra

Cayenne

Sandra

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Marian

Myrrh

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Goblin

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Marian

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Cayenne

Myrrh

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

PRAISE FOR MYRRH

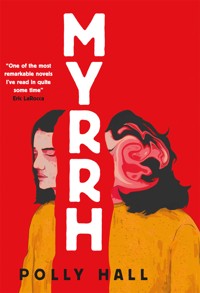

“Clever, insightful, and insidiously vicious, Polly Hall’s Myrrh is a terrifying and profoundly visceral exploration of social appearances, identity, and family. One of the most remarkable novels I’ve read in quite some time.”

Eric LaRocca, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

§

“Myrrh swirls with sharp prose and personality. A dynamite stick of a book, pregnant with pathos and nitroglycerin.”

Hailey Piper, Bram Stoker® Finalist, and author of A Light Most Hateful

§

“Nothing can quite prepare you for the gift that is Myrrh, which mischievously reads like an unhinged Rumplestiltskin, a Daphne du Maurier suckerpunch, a Catriona Ward whirlpool of vertiginous proportions. Remember the name Polly Hall. Her novel breathes life in the gathering gloom.”

Clay McLeod Chapman, author of What Kind of Mother and Ghost Eaters

§

“A festering account of the horrors women hold within their wombs, and the ones their daughters inherit.”

Lindy Ryan, author of Bless Your Heart and Cold Snap

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Myrrh

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789095357

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364971

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organisations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Polly Hall 2024

Polly Hall asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For my family

Myrrh

from Arabic ‘bitter’

Myrrh is harvested by repeatedly wounding the treeto make it bleed tears of aromatic gum.

Maybe I was just born bad. But I was only taking what was rightfully mine. It might be easier for you if I told you I had a brutal, abusive childhood, or if I was moulded this way by neglectful parents or a husband who beat me senseless. You might find it easier to comprehend if I had been driven mad with grief by the loss of a child or endured endless cycles of poverty and torment. You might feel less uncomfortable if you could understand or pin a reason on why I did it. But I haven’t experienced any more hardship than most. My mundane existence was rather comfortable, nothing out of the ordinary. I was never marked out as the ‘problem child’ or tearaway; I rarely broke the rules. I didn’t torture animals or self-harm when I was a kid. My habits were no unhealthier than yours. You’ll scout over all the details of how, when, who and still be left wondering why.

I did something you could never imagine doing and that is what puts me on the other side of the wall from you. Not just a hard stone wall but a fragile wall of glass, cold to the touch and, for now, uncracked.

MYRRH

Myrrh thought about how branches of trees in the wind were like hair, but when it was calm those same branches looked like pencil sketches of capillaries in a dissected heart or lungs. We are trained to look at the surface and make assumptions on how things appear, she thought. We notice the cute button noses and skin tone; we congratulate friends on shedding pounds of flesh or having their hair cut and styled by a stranger; our eyes flick towards big tits or fat buttocks or bushy eyebrows or scars without even knowing we are doing it. All these noticeable things, these superficial things.

On the journey back to the coast she stopped at a petrol station because, although her fuel light had not reminded her that fuel was low, she liked to plan ahead and be prepared so she would not be put in a situation where, heaven forbid, she was stranded on an unfamiliar road with no means to go forward or back or anywhere at all. Who were these unprepared people who never checked that they had all they needed before a journey, the renegades who spontaneously crashed through life leaping like a monkey swinging from the treetops, barely grasping one vine before reaching towards the next? She needed a level of certainty but secretly admired the messy, chaotic, mindless rushed lives of others.

She picked up her phone to see no new messages, so flicked through the photos from the past few days: the trees, the sunset, a lone figure on a bench looking out to a park, a blurry shot of a house, a street-name sign, the sky above the town and the rooftops dotted with resting pigeons. It all seemed so anonymous, so unfamiliar, so unlike her life by the coast. Did she expect a message from them, from him? An apology. Anything?

worthless

useless

She tried to remember the first time she had ever seen the sea and recalled it as a sound like trees in a storm, mingled with a scent like all things dead and alive at the same time, a preserved living-dead thing, and she felt drawn to it, but also wary of it; and there were spaces between the sounds, little pauses, like the white spaces between text on the pages of a book. And she wondered why people spoke of the sea like it was calming and restorative when it mostly destroyed things in it, on it or beside it, how it was filled with creatures munching their way through each other, currents grinding and crushing and mashing in an endless briny cycle.

When she returned home, she didn’t know whether she would tell anyone about what happened. Switching to practical matters, quantifying the trouble and upheaval of changing who she was, who she had grown attached to, but realising it meant nothing to anyone else. Didn’t everyone have a terribly complex backstory of their own? A life filled with stuff you just didn’t talk about?

As the fuel filled up in her tank she watched as an estate car, full of family, pull up to the pump beside her: two adults, two children, a bootful of holiday belongings crammed against the rear windscreen. One of the kids, a young girl of about ten, stared at her from the backseat. Myrrh looked away, then back again, ready to offer a smile, but the girl poked out her tongue and wrinkled up her nose. The girl had red hair and freckles that would’ve been brought out by the sun as she clambered over rockpools or darted in and out of the surf, ignoring her mother’s pleas of ‘Not too far,’ or ‘Don’t go in too deep’.

‘That’s not what I meant…’ The mother’s voice sliced the air like sharpened fingernails as she stepped from the driver’s seat and slammed her car door. The young girl in the backseat continued staring out her window at Myrrh.

The man in the front passenger seat sat motionless yet full of suppressed explosives. Myrrh imagined that inside him was a battalion of armour-plated locusts ready to spew out of his mouth, but he kept it shut because if he dared open it to speak the locusts would burst free and strip all the flesh off his wife, leaving her as just a pile of bones on the forecourt in front of her screaming children. That is why he remains silent, Myrrh thought, and why he keeps very still, because if he moves there is a possibility everyone will die and it would be on his conscience that he had let the killer locusts out to do what killer locusts do best.

Myrrh looked up at the flickering display of numbers on the petrol pump, aware of the oily scent filling her nostrils. On the surface, she probably appeared well-adjusted, rational, diplomatic even, but the goblin knew otherwise. She realised then that if she were that other woman – the mother of that family – driving home from a short holiday, she might consider driving herself and her offspring and husband, with his latent flesh-eating locust tendencies, off a cliff and down to the unforgiving rocks below.

Goblin smirked

Myrrh thought of all the people she’d like to put in the car with her if she were to drive off that cliff onto the rocks below and decided she’d need a bigger vehicle and wouldn’t it just be an act of kindness rather than murder, and through death she’d be associated with them forever, when in life she hadn’t been and the cruel irony of it all.

Goblin cackled

And Myrrh thought that one spontaneous act of passionate murder would not be enough to portray how much those people, who she had chosen to die with rather than have the choice to live with, had fucked up her life, and perhaps a more direct act, like stabbing or strangling or bashing their skulls in with a tin of baked beans, would be a more satisfying course of action.

The petrol pump noisily clicked and kicked back against her hand. She drew a breath to remove herself from her train of thought and finished paying at the pump. The woman from the estate car emerged from the kiosk, jogged quickly to the car, and launched plastic bottles of cola and bags of snacks onto her husband’s lap as she got back in the driver’s seat and started the engine.

pour it in their car

douse them with it

burn them all

Myrrh watched that family drive away toward their own cliff and their own rocks. She thought about their shared DNA and the inexplicable link between the girl’s red hair and the mother’s red hair and the constellation of freckles on their cheeks and their eyes, noses, mouths and those shapes that connected them. And she thought of the ways her own family tried to make those physical connections that were not there, grasping at the ungraspable, pressing heavily on jigsaw pieces with the wrong edges to try and make them fit, knowing that there was no way they would fit, because they were from different jigsaws with different-shaped pieces. But they carried on believing there was a connection because, if they didn’t, what or who would stop the goblins breaking free and wreaking havoc with cars and knives and tins of baked beans.

‘Please,’ she said to Goblin. ‘Please stop.’

burn them all

burn it all down

CAYENNE

It all starts with a look. His eyes are not as dark as mine. We are different creatures. However, I know we will end up together. Fate. He is the one who lifts me up from the gutter and I cling on to that hope. Those long lingering gazes as if we can read each other’s minds. Caught in a whirlwind, feet-sweeping exhilaration. His attention excites me, the way he sticks his nails under mine when we hold hands, the lingering squeeze of his hand on my thigh, always at each other’s side. I want to breathe him in, to consume him. I want to feel the cut and burn of his promises on my body.

He keeps me poised on a precipice. You’ll never want for anything. You are the love of my life. We will live happily ever after. He has all the silky, smooth words to wrap us up in.

Princess. He rarely uses my actual name. I am his princess. Does that make him my prince? Or my knight in shining armour, saving this damsel in distress from her predicament? It’s all twinkly lights and forest glades. It’s soft moonlight and skin.

MYRRH

When Myrrh was a teenager, she thought of all the things she would like to shout at her birth mother when they eventually met. Her moods ricocheted between longing and rage, fictitious meetings like those sickly reunion programmes she found difficult to watch on television. She became the adopted daughter she was expected to be, and each time she moved further away from her beginning she felt that ugly churning prompted by the goblin. On top of all the troubles heaped on her teenage self, confusion spilled down her cheeks in hot tears of unspoken angst towards her biological mother:

Why did you not plan your future? My future? Why did you not keep me? Why did you not have an abortion? Do you love me? I don’t love you. I don’t care if you’re dead. I won’t know when you die. You are not my relation. Who are you anyway? I am your child. I am not your child. I’m not sorry for the choices you have made that omit me. You are everything I expected and more. You are a disappointment. Why did you sleep with him? Why is it not black and white? Am I black or white? Why can’t you fit the picture I have of you in my mind? Do you think of me? Where have you been? Have you tried to find me? Where is my father? Who is he? Why didn’t you stay together? Who is he with now who fulfils him in ways that you never did? Where do I come from? Who the fuck am I?

CAYENNE

‘Yes,’ I gasp. He is holding my face in his hands and I am crying happy tears. The question is barely out of his mouth before he receives my answer. ‘Yes,’ I say again and kiss him.

I am surprised but try not to let the gratitude dip into desperation. He wipes the tears from my cheeks with his thumbs. I feel his rough skin graze against mine.

‘You are happy I asked, aren’t you?’ he asks.

I kiss him over and over on his lips, his face, the palms of his hands.

‘I’m more than happy,’ I tell him. ‘It’s a dream come true.’ Am I acting too needy?

Is it a dream? This man is asking me to be part of his family. All of us together. Me, him, his daughter, a family. It’s all I’ve ever wanted. I look around the room and have already decided what colour to repaint the walls. I have already catalogued in my mind the things that must go.

CAYENNE

‘Have you been in my room?’ she asks.

‘No,’ I reply and turn to face her. She has a peachy doll face that helps her get away with far too much. But there is a hard edge there. She gets that from her father.

‘Oh right, funny…’ She sniffs and wipes the back of her hand across her button nose. ‘My hairbrush has moved.’

Is she accusing me of something?

‘Are you accusing me of moving your stuff?’ I ask. It comes out too harsh so I laugh to soften the words, make light of it. But inside my tummy turns on itself.

‘Just wondered,’ she says. She is sidling around the kitchen, moving ornaments from the dresser and tracing her fingers along the shelves before inspecting them. She inhales long and loud. ‘Those flowers look rank.’ She gestures to the row of pelargoniums I have added to the windowsills.

‘I think they brighten up the place.’ I won’t let her dampen my mood.

‘It’s like an old people’s home.’ She doesn’t laugh and slumps down at the kitchen table.

I carry on stirring the sauce in the pan. She is happy enough to eat what I cook every night and leave her soiled empty plate on the table for me to clear up after her.

‘When’s Dad home?’ she asks.

‘I’m not sure,’ I say. But when I turn she is gone and the sauce has split. I’ll have to start over.

CAYENNE

I wake from a fitful sleep feeling despondent, my insides thick with uncertainty and gloom. It is my birthday. You’d think by now he wouldn’t need reminding. He needs at least three months’ notice. I tear open the envelope and fake a smile. A large, embossed, puke-inducing card: To The One I Love, I Love You With All My Heart, blah blah blah. Maybe he does actually love me, but he hasn’t had the forethought or stamina to give me what I really want.

He hands me a weak cup of tea then limply wraps his arms around my waist. I endure this for several seconds then twist out of his embrace, faking a coughing fit.

He must know something is wrong, but it is futile to put into words how I feel. I get the same old nagging feeling that my life might be heading for a cliff edge, especially now I have broached the difficult question of us having a child together. Time is not on my side. I want to be in love; I want the fairytale; I need the happily ever after. A flare of anger lights up my cheeks as I think how much we have to depend on men to give this to us. One small thrusting act of pleasure and their part in the story can end if they so wish.

It is my birthday. There will be booze and with any luck I can drink until I pass out and we will fumble in the dark until we are both sticky and spent from our exertions and maybe, just maybe, I will conceive.

MYRRH

Mrs Mackman saw in the child a part of her that wanted to run like a wild horse, nostrils flaring, hot steam escaping from her lungs. Her will was like steel, like petrol to a flame.

‘That baby is like a symphony,’ she would remark. ‘I’ve seen enough of them come and go.’

She’d scoop her up in her arms but found it difficult to contain the wriggling, all arms and legs pumping as if she were a piston engine, as if she were trying to escape. It was as if the child needed to move or would seize up, turn to stone.

There were times when she truly thought these children that came and went were part of her clan. Places were always laid at the table just as she laid George’s place when he was at sea. A superstitious fisherman’s wife was how she thought others regarded her. She couldn’t have been further from the truth. She was admired for all she did with those waifs and strays. She was the temporary lifebuoy for those stormy lives.

‘What’s expected will come to those who wait.’ Her determined but kind voice seemed to soothe those wayward souls much as she’d done for her own flesh and blood.

Mrs Mackman would sing in a voice – sweet and light – that didn’t quite fit with her solid, rotund body. She produced an upbeat melodic sound that warmed the small cottage where hundreds of children had passed through, anticipating love, unaware of their fate, waiting for parents or guardians to take them to a forever home.

She only sang when no one else was in the room with her. Her voice carried like a siren’s call. As if she sang secrets of the deep. She knew the sea and how it could take her husband from her in an instant with no warning. Her superstitions grew larger at night-time when George was out on a late tide. That was why she busied herself with the children. They were her mainstay, with their funny little patterns, the ebb and flow of their instincts.

‘I worry about them all,’ she explained to her friend and neighbour, Mrs Willows. ‘But she’s different. I don’t know how to explain it.’

‘A bit odd?’ Mrs Willows offered unhelpfully while looking over at the row of nap cloths drying by the fire then back at the baby, who nuzzled a bottle and wrinkled up its tiny features. It could be a changeling, she thought. A fairy child. A creature from another world. She could tell its skin was darker than the others but made no comment.

‘No, not odd. Just different, more aware.’

There had been a hold up with paperwork so they’d called her up for an emergency placement, short-term foster care. Plenty of new parents waiting, though, they told her as they bundled the tiny infant into her arms with only her hospital clothes and nothing more. She didn’t doubt it. But there were plenty of parentless children too.

Mrs Mackman shared tea and scones with a few of her friends as part of a ritual to dilute the daily chores with what she liked to call a ‘sit-down’. She had been taking in children for years, some damaged beyond repair even when she mined the well of her compassion, to soak them with love until they were packed off to some other foster home or, on occasions, placed with a suitable family. It was best not to keep mementoes or dwell on the tears and tantrums.

‘I don’t normally let them get to me,’ she told Mrs Willows one afternoon. ‘Would you call me sentimental?’

Mrs Willows shook her head. ‘Not you,’ she said. ‘No, not sentimental at all.’

George was not due home until the early morning, and she knew she would not sleep. His absence coincided with a new boy joining the household. He had ‘significant problems with truancy’, the social worker had reminded her. Mrs Mackman had nodded and smiled. Running away was not an issue, she thought. It was what you were running towards that seemed to cause most hassle.

Most of them were masters at manipulation, vying for attention in the hope that it would reap a reward or two. It never worked. She treated each one of them fairly, and they soon got to learn that she would not budge in her opinion or routine. It was her house and her rules. That said, Mrs Mackman would accept their little gifts honestly and sincerely: a posy of wilting weeds, a bow tie fashioned from a used crisp wrapper or, at Easter time, painted crosses or decorated eggs they’d bring home from school classes. But after they had left her home, she’d carefully untack the paper art from the walls and doors or lift the dusty craftwork from her shelves and incinerate them in the garden, watching black flecks of ash disintegrate before her eyes. It was best that way: to move on and make way for the new.

She cleared the mugs and went out to the garden to retrieve the washing from the line. Two children – only six and seven, a brother and sister – were due home from school. It was a fair day, but she would still listen to the shipping forecast later, religiously, as a habit. She didn’t really understand the rise and fall but liked to hear the names meditatively pronounced: Fitzroy, Rockall, German Bight. She pretended they were mythical creatures being conjured up from deep beneath the ocean.

The baby girl was sleeping in her crib now. She slept all day mostly. At night she lay awake staring at the ceiling watching out for some unseen thing, eyes wide and glistening as she bawled in that spectral way babies do. No amount of soothing or milk seemed to placate her during the wee small hours. She had a look like she’d been here before, that she knew some unspeakable thing but could not yet verbalise it. Her tiny fists were bunched up in cotton mittens that seemed a little pointless, her cheeks already covered in scratches. While trimming her nails to the quick Mrs Mackman could’ve sworn the baby uttered profanities, sounds emerging like wicked swear words that would even make her fisherman husband blush. But the child was far too young to speak. She was only a babe not long out of the womb, bless her poor soul.

Mrs Mackman turned on the wireless and caught the end of the news, shock in a small town, a young pregnant woman was missing, and the newsreaders spoke about neighbours fearing for her safety and the safety of her unborn child.

CAYENNE

I tread on eggshells. I change my plans. I shapeshift into their life.

She lays it on thick that she is his only daughter, his only family. Just because you are related to someone doesn’t mean you own them.

‘You may resent me because your father loves me. He says he loves me more than anything. More than you? Would you ever believe it? I naïvely thought we could get along at the start, but I have seen too many times how you try to exclude me. He says you’re too unimaginative to do this, but I don’t underestimate you the way he does.

‘This house is not a home for me while you are in it. The way you childishly sit on his lap even though you are a grown woman; the way you share your thoughts with him while ignoring my direct questions; the way you speak to him in that whiny baby voice. It’s all bullshit. Grow up! We have put our plans on hold because of you. I want children. You won’t always be his number one.’

Of course, I would never say any of this to her face. It is all holed up inside me like a nest of vipers. Maybe I will have hordes of children with him, all vying for his affections, and she will be snapped up by a man of her own or become the handless maiden. Chop, chop. She cannot remain pure forever. We must all make sacrifices for our family.

At first, he may just forget the little things, like the way she walks or blinks. Then her voice, and, as time passes and our new family begins to edge into his daily life, he will find there are hours, days, weeks when he doesn’t think of her at all.

She says she’s not fussed by what he does or what I do. In my experience when people say they don’t care, they do. A lot.

MYRRH

Myrrh was born on a Thursday (Thursday’s child has far to go). Perhaps the childhood saying had a maxim of truth behind its rhyme. She had moved far from her cultural and genetic roots and the hardest part was letting go of that fact. She tenaciously held onto the belief that the answer to her nature lay in the unknown past. Perhaps it meant the journey was to return to the start, like the pilgrim who travelled across many lands to seek his treasure when all along it was buried beneath his feet. If she held on to that belief, something like an invisible thread tightened around her will, as if she were being pulled back to the beginning. She felt like a child in a fairytale using breadcrumbs to find her way back home, only to realise she was not only lost but hungry too.

Summer suited her. She could blossom and express her fullness, her smile radiant and her body melting the constriction of the cold, dark winter months. Born in August, at the height of summer in a year that blistered and crackled from excessive heat, there seemed to be a rigidity set in her, like the apparent dryness of a desert. Like the desert, she housed beauty and terror in many guises.

When she turned nine, her parents organised a birthday party. Sandwiches made from gluey white bread. Sickly iced cupcakes piled onto plates. Jelly and ice cream slopped into bowls. And curly worm-like crisps stained lips and fingers with orange dust.

It was a small affair with mainly friends from her neighbourhood. If she knew at that age the path that lay ahead, would she have allowed herself to enjoy that moment? It was a party, not a wake, but she was constantly anticipating drama, a broken glass slicing through tender skin or someone feeling left out during the games and the incessant malevolent whisper of the goblin

this will never last, this will never last

bite your tongue and fill your mouth with blood

stuff it in

stuff it down

choke on it

The plates smeared with half-eaten sponge cake were stacked by the kitchen sink, jam tarts scattered like Alice in Wonderland extras across the lawn. Myrrh had said goodbye to her friends and sat alone on her bed feeling sick. She thought it was from too much cake, but as she drew her knees up to her chest there was something else bothering her insides. She rushed to the toilet and threw up.

you can’t squash me down

I’ll always be here

I am meant to be here

She retched but there was nothing more to come up. Flecks of her birthday party spattered the toilet bowl.

Did these creatures taunt everyone? And where had he come from? Was that the moment she realised she was cursed?

CAYENNE

I am feeling gracious. Overwhelming generosity flows out of me. I decide to talk with his daughter to find common ground. I feel we can work on our complicated relationship. It is all I’ve ever wanted. I know I am not perfect, but I want her to see I am human, that I have feelings too. I will never be her mother, she will never be my daughter, but perhaps there is a chance we can work something out.

Our conversation goes something like this:

Me: I’d like to talk to you. When are you free? Tonight?

Her: No. Maybe tomorrow.

Me: Okay. Let’s talk tomorrow, have a proper conversation.

Her: Whatever.

This is what annoys the hell out of me: her apparent indifference and the certainty that she will win whatever battle she thinks we are fighting. Does she know the leverage she has over her father is stronger than mine ever will be? I am powerless to exert any control over the situation unless I change my mindset.

I am not her parent, but I have been thrown into this role. My words bounce off her, we speak in foreign tongues, her words, my words, all layered together and incoherent. I try to say, ‘I’m here for you.’ She does not need me. She will never need me. One motherless child speaking to another motherless child about something neither of us understand.

Is it easier if the child is from your womb?

MYRRH

There must’ve been a first time her tongue recorded the moment when the sweetness tricked her into thinking it was good for her. Now nostalgia would seep down her throat whenever she twisted the wrapper. It was too tempting to just suck the sweet, to delay its dissolving pleasure, so she’d crunch it, letting fragments mould into her teeth like temporary fillings.

‘Caramel?’ Myrrh asked. Her therapist raised his eyebrows as she tried to explain. That was what the memory tasted like. He said that all the senses must be employed to fully experience the memory, so she latched upon caramel. It sounded as dreamy as its taste.

‘Am I cursed?’ she asked him.

‘Cursed? How?’

‘Because I didn’t have a choice. My fate was already decided.’

‘That’s the same for all of us when we’re born.’

‘But not everyone is given away, adopted. Not everyone has a mum, dad, brother or sister out there somewhere they know nothing about.’

‘Can I ask what is stopping you from finding them, if you wanted to?’

She thought about the tin in the wardrobe at the house she grew up in. That treasure trove of history and information. Right there for her. But then she heard the goblin, his voice growing stronger and stronger

you know nothing

you are nothing

little orphan girl

given up

thrown away

take his pen and stab him in the eye

watch him bleed

make him see

and stronger still the closer the truth got. No. She couldn’t go back there. Not yet.

Myrrh gazed around the room and her eyes settled on a painting on the wall. It was a surreal image: a wheel in the centre crossed like a compass with symbols she did not recognise. Stationed at the surrounding edges were mythical creatures – a griffin, and a winged cow and lion, and an angel – all holding books. A sphinx crouched at the top cradling a sword, and a snake was entwined down the left side of the wheel. Below, almost in the same shade of orange as the wheel and shaped around the edge of the painting, was a human figure with the head of a dog, like the depictions she had seen of ancient Egyptian gods.

‘What is it meant to be?’

Myrrh studied the image, imagining this woman painting each design, dreaming up something new from old wisdom.

‘This one is the Wheel of Fortune,’ he said. ‘Fate. You can find a lot of symbolism in the artwork.’

Fate as a wheel, thought Myrrh. Always ready to off-road towards you and smack you down flat. What if her fate was to never know where she had come from, who she was?

‘It’s from the major arcana. These are archetypes. We all have elements of the cards playing out in our lives: new beginnings, disaster, trauma, healing… I’d like to study them more in my work. The Fool’s Journey.’

disaster

trauma

‘The Fool’s Journey?’

‘It’s all the initiations and pathway we take in life, the ups and downs…’

‘Who painted it?’

‘Pamela Colman Smith. She was the original artist commissioned to paint the cards by a mystic and poet. She designed and painted seventy-eight cards of the deck.’

Myrrh looked again at the vibrant colours and imagined this woman painting, alone. Each dream-like image conjured from the imagination onto paper.

‘Where are the original paintings now?’ The passing of time, all that effort buried or broken, moved or displaced by other peoples’ actions.

‘No one knows; everything was sold when she died. She had a house in Cornwall.’ Cornwall. Her birth mother’s address. They both stood in front of the painting in silence observing the vibrancy as it danced and merged. Broken or displaced, she thought. Could people be broken like objects?

your mother didn’t want you

your mother didn’t want you

Goblin was awake. She was thinking about her birth mother again, about what she looked like, who she was.

who are you?

you are nobody