Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Narrative of the Life of Frederick DouglassPREFACELETTER FROM WENDELL PHILLIPSFREDERICK DOUGLASS.CHAPTER ICHAPTER IICHAPTER IIICHAPTER IVCHAPTER VCHAPTER VICHAPTER VIICHAPTER VIIICHAPTER IXCHAPTER XCHAPTER XIAPPENDIXCopyright

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

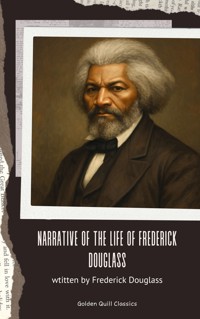

Frederick Douglass

PREFACE

In the month of August, 1841, I attended an anti-slavery

convention in Nantucket, at which it was my happiness to become

acquainted withFrederick Douglass, the

writer of the following Narrative. He was a stranger to nearly

every member of that body; but, having recently made his escape

from the southern prison-house of bondage, and feeling his

curiosity excited to ascertain the principles and measures of the

abolitionists,—of whom he had heard a somewhat vague description

while he was a slave,—he was induced to give his attendance, on the

occasion alluded to, though at that time a resident in New

Bedford.Fortunate, most fortunate occurrence!—fortunate for the

millions of his manacled brethren, yet panting for deliverance from

their awful thraldom!—fortunate for the cause of negro

emancipation, and of universal liberty!—fortunate for the land of

his birth, which he has already done so much to save and

bless!—fortunate for a large circle of friends and acquaintances,

whose sympathy and affection he has strongly secured by the many

sufferings he has endured, by his virtuous traits of character, by

his ever-abiding remembrance of those who are in bonds, as being

bound with them!—fortunate for the multitudes, in various parts of

our republic, whose minds he has enlightened on the subject of

slavery, and who have been melted to tears by his pathos, or roused

to virtuous indignation by his stirring eloquence against the

enslavers of men!—fortunate for himself, as it at once brought him

into the field of public usefulness, "gave the world assurance of a

MAN," quickened the slumbering energies of his soul, and

consecrated him to the great work of breaking the rod of the

oppressor, and letting the oppressed go free!I shall never forget his first speech at the convention—the

extraordinary emotion it excited in my own mind—the powerful

impression it created upon a crowded auditory, completely taken by

surprise—the applause which followed from the beginning to the end

of his felicitous remarks. I think I never hated slavery so

intensely as at that moment; certainly, my perception of the

enormous outrage which is inflicted by it, on the godlike nature of

its victims, was rendered far more clear than ever. There stood

one, in physical proportion and stature commanding and exact—in

intellect richly endowed—in natural eloquence a prodigy—in soul

manifestly "created but a little lower than the angels"—yet a

slave, ay, a fugitive slave,—trembling for his safety, hardly

daring to believe that on the American soil, a single white person

could be found who would befriend him at all hazards, for the love

of God and humanity! Capable of high attainments as an intellectual

and moral being—needing nothing but a comparatively small amount of

cultivation to make him an ornament to society and a blessing to

his race—by the law of the land, by the voice of the people, by the

terms of the slave code, he was only a piece of property, a beast

of burden, a chattel personal, nevertheless!A beloved friend from New Bedford prevailed

onMr. Douglassto address the convention:

He came forward to the platform with a hesitancy and embarrassment,

necessarily the attendants of a sensitive mind in such a novel

position. After apologizing for his ignorance, and reminding the

audience that slavery was a poor school for the human intellect and

heart, he proceeded to narrate some of the facts in his own history

as a slave, and in the course of his speech gave utterance to many

noble thoughts and thrilling reflections. As soon as he had taken

his seat, filled with hope and admiration, I rose, and declared

thatPatrick Henry, of revolutionary fame,

never made a speech more eloquent in the cause of liberty, than the

one we had just listened to from the lips of that hunted fugitive.

So I believed at that time—such is my belief now. I reminded the

audience of the peril which surrounded this self-emancipated young

man at the North,—even in Massachusetts, on the soil of the Pilgrim

Fathers, among the descendants of revolutionary sires; and I

appealed to them, whether they would ever allow him to be carried

back into slavery,—law or no law, constitution or no constitution.

The response was unanimous and in thunder-tones—"NO!" "Will you

succor and protect him as a brother-man—a resident of the old Bay

State?" "YES!" shouted the whole mass, with an energy so startling,

that the ruthless tyrants south of Mason and Dixon's line might

almost have heard the mighty burst of feeling, and recognized it as

the pledge of an invincible determination, on the part of those who

gave it, never to betray him that wanders, but to hide the outcast,

and firmly to abide the consequences.It was at once deeply impressed upon my mind, that,

ifMr. Douglasscould be persuaded to

consecrate his time and talents to the promotion of the

anti-slavery enterprise, a powerful impetus would be given to it,

and a stunning blow at the same time inflicted on northern

prejudice against a colored complexion. I therefore endeavored to

instil hope and courage into his mind, in order that he might dare

to engage in a vocation so anomalous and responsible for a person

in his situation; and I was seconded in this effort by warm-hearted

friends, especially by the late General Agent of the Massachusetts

Anti-Slavery Society,Mr. John A. Collins,

whose judgment in this instance entirely coincided with my own. At

first, he could give no encouragement; with unfeigned diffidence,

he expressed his conviction that he was not adequate to the

performance of so great a task; the path marked out was wholly an

untrodden one; he was sincerely apprehensive that he should do more

harm than good. After much deliberation, however, he consented to

make a trial; and ever since that period, he has acted as a

lecturing agent, under the auspices either of the American or the

Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. In labors he has been most

abundant; and his success in combating prejudice, in gaining

proselytes, in agitating the public mind, has far surpassed the

most sanguine expectations that were raised at the commencement of

his brilliant career. He has borne himself with gentleness and

meekness, yet with true manliness of character. As a public

speaker, he excels in pathos, wit, comparison, imitation, strength

of reasoning, and fluency of language. There is in him that union

of head and heart, which is indispensable to an enlightenment of

the heads and a winning of the hearts of others. May his strength

continue to be equal to his day! May he continue to "grow in grace,

and in the knowledge of God," that he may be increasingly

serviceable in the cause of bleeding humanity, whether at home or

abroad!It is certainly a very remarkable fact, that one of the most

efficient advocates of the slave population, now before the public,

is a fugitive slave, in the person ofFrederick

Douglass; and that the free colored population of the

United States are as ably represented by one of their own number,

in the person ofCharles Lenox Remond,

whose eloquent appeals have extorted the highest applause of

multitudes on both sides of the Atlantic. Let the calumniators of

the colored race despise themselves for their baseness and

illiberality of spirit, and henceforth cease to talk of the natural

inferiority of those who require nothing but time and opportunity

to attain to the highest point of human excellence.It may, perhaps, be fairly questioned, whether any other

portion of the population of the earth could have endured the

privations, sufferings and horrors of slavery, without having

become more degraded in the scale of humanity than the slaves of

African descent. Nothing has been left undone to cripple their

intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature,

obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; and yet how

wonderfully they have sustained the mighty load of a most frightful

bondage, under which they have been groaning for centuries! To

illustrate the effect of slavery on the white man,—to show that he

has no powers of endurance, in such a condition, superior to those

of his black brother,—Daniel O'connell,

the distinguished advocate of universal emancipation, and the

mightiest champion of prostrate but not conquered Ireland, relates

the following anecdote in a speech delivered by him in the

Conciliation Hall, Dublin, before the Loyal National Repeal

Association, March 31, 1845. "No matter," saidMr.

O'connell, "under what specious term it may disguise

itself, slavery is still hideous.It has a natural, an

inevitable tendency to brutalize every noble faculty of man.An American sailor, who was cast away on the shore of Africa,

where he was kept in slavery for three years, was, at the

expiration of that period, found to be imbruted and stultified—he

had lost all reasoning power; and having forgotten his native

language, could only utter some savage gibberish between Arabic and

English, which nobody could understand, and which even he himself

found difficulty in pronouncing. So much for the humanizing

influence ofThe Domestic Institution!"

Admitting this to have been an extraordinary case of mental

deterioration, it proves at least that the white slave can sink as

low in the scale of humanity as the black one.Mr. Douglasshas very properly chosen to write

his own Narrative, in his own style, and according to the best of

his ability, rather than to employ some one else. It is, therefore,

entirely his own production; and, considering how long and dark was

the career he had to run as a slave,—how few have been his

opportunities to improve his mind since he broke his iron

fetters,—it is, in my judgment, highly creditable to his head and

heart. He who can peruse it without a tearful eye, a heaving

breast, an afflicted spirit,—without being filled with an

unutterable abhorrence of slavery and all its abettors, and

animated with a determination to seek the immediate overthrow of

that execrable system,—without trembling for the fate of this

country in the hands of a righteous God, who is ever on the side of

the oppressed, and whose arm is not shortened that it cannot

save,—must have a flinty heart, and be qualified to act the part of

a trafficker "in slaves and the souls of men." I am confident that

it is essentially true in all its statements; that nothing has been

set down in malice, nothing exaggerated, nothing drawn from the

imagination; that it comes short of the reality, rather than

overstates a single fact in regard toslavery as it

is. The experience ofFrederick

Douglass, as a slave, was not a peculiar one; his lot

was not especially a hard one; his case may be regarded as a very

fair specimen of the treatment of slaves in Maryland, in which

State it is conceded that they are better fed and less cruelly

treated than in Georgia, Alabama, or Louisiana. Many have suffered

incomparably more, while very few on the plantations have suffered

less, than himself. Yet how deplorable was his situation! what

terrible chastisements were inflicted upon his person! what still

more shocking outrages were perpetrated upon his mind! with all his

noble powers and sublime aspirations, how like a brute was he

treated, even by those professing to have the same mind in them

that was in Christ Jesus! to what dreadful liabilities was he

continually subjected! how destitute of friendly counsel and aid,

even in his greatest extremities! how heavy was the midnight of woe

which shrouded in blackness the last ray of hope, and filled the

future with terror and gloom! what longings after freedom took

possession of his breast, and how his misery augmented, in

proportion as he grew reflective and intelligent,—thus

demonstrating that a happy slave is an extinct man! how he thought,

reasoned, felt, under the lash of the driver, with the chains upon

his limbs! what perils he encountered in his endeavors to escape

from his horrible doom! and how signal have been his deliverance

and preservation in the midst of a nation of pitiless

enemies!This Narrative contains many affecting incidents, many

passages of great eloquence and power; but I think the most

thrilling one of them all is the

descriptionDouglassgives of his

feelings, as he stood soliloquizing respecting his fate, and the

chances of his one day being a freeman, on the banks of the

Chesapeake Bay—viewing the receding vessels as they flew with their

white wings before the breeze, and apostrophizing them as animated

by the living spirit of freedom. Who can read that passage, and be

insensible to its pathos and sublimity? Compressed into it is a

whole Alexandrian library of thought, feeling, and sentiment—all

that can, all that need be urged, in the form of expostulation,

entreaty, rebuke, against that crime of crimes,—making man the

property of his fellow-man! O, how accursed is that system, which

entombs the godlike mind of man, defaces the divine image, reduces

those who by creation were crowned with glory and honor to a level

with four-footed beasts, and exalts the dealer in human flesh above

all that is called God! Why should its existence be prolonged one

hour? Is it not evil, only evil, and that continually? What does

its presence imply but the absence of all fear of God, all regard

for man, on the part of the people of the United States? Heaven

speed its eternal overthrow!So profoundly ignorant of the nature of slavery are many

persons, that they are stubbornly incredulous whenever they read or

listen to any recital of the cruelties which are daily inflicted on

its victims. They do not deny that the slaves are held as property;

but that terrible fact seems to convey to their minds no idea of

injustice, exposure to outrage, or savage barbarity. Tell them of

cruel scourgings, of mutilations and brandings, of scenes of

pollution and blood, of the banishment of all light and knowledge,

and they affect to be greatly indignant at such enormous

exaggerations, such wholesale misstatements, such abominable libels

on the character of the southern planters! As if all these direful

outrages were not the natural results of slavery! As if it were

less cruel to reduce a human being to the condition of a thing,

than to give him a severe flagellation, or to deprive him of

necessary food and clothing! As if whips, chains, thumb-screws,

paddles, blood-hounds, overseers, drivers, patrols, were not all

indispensable to keep the slaves down, and to give protection to

their ruthless oppressors! As if, when the marriage institution is

abolished, concubinage, adultery, and incest, must not necessarily

abound; when all the rights of humanity are annihilated, any

barrier remains to protect the victim from the fury of the spoiler;

when absolute power is assumed over life and liberty, it will not

be wielded with destructive sway! Skeptics of this character abound

in society. In some few instances, their incredulity arises from a

want of reflection; but, generally, it indicates a hatred of the

light, a desire to shield slavery from the assaults of its foes, a

contempt of the colored race, whether bond or free. Such will try

to discredit the shocking tales of slaveholding cruelty which are

recorded in this truthful Narrative; but they will labor in

vain.Mr. Douglasshas frankly disclosed

the place of his birth, the names of those who claimed ownership in

his body and soul, and the names also of those who committed the

crimes which he has alleged against them. His statements,

therefore, may easily be disproved, if they are

untrue.In the course of his Narrative, he relates two instances of

murderous cruelty,—in one of which a planter deliberately shot a

slave belonging to a neighboring plantation, who had

unintentionally gotten within his lordly domain in quest of fish;

and in the other, an overseer blew out the brains of a slave who

had fled to a stream of water to escape a bloody

scourging.Mr. Douglassstates that in

neither of these instances was any thing done by way of legal

arrest or judicial investigation. The Baltimore American, of March

17, 1845, relates a similar case of atrocity, perpetrated with

similar impunity—as follows:—"Shooting a

slave.—We learn, upon the authority of a letter from

Charles county, Maryland, received by a gentleman of this city,

that a young man, named Matthews, a nephew of General Matthews, and

whose father, it is believed, holds an office at Washington, killed

one of the slaves upon his father's farm by shooting him. The

letter states that young Matthews had been left in charge of the

farm; that he gave an order to the servant, which was disobeyed,

when he proceeded to the house,obtained a gun, and,

returning, shot the servant.He immediately, the letter

continues, fled to his father's residence, where he still remains

unmolested."—Let it never be forgotten, that no slaveholder or

overseer can be convicted of any outrage perpetrated on the person

of a slave, however diabolical it may be, on the testimony of

colored witnesses, whether bond or free. By the slave code, they

are adjudged to be as incompetent to testify against a white man,

as though they were indeed a part of the brute creation. Hence,

there is no legal protection in fact, whatever there may be in

form, for the slave population; and any amount of cruelty may be

inflicted on them with impunity. Is it possible for the human mind

to conceive of a more horrible state of society?The effect of a religious profession on the conduct of

southern masters is vividly described in the following Narrative,

and shown to be any thing but salutary. In the nature of the case,

it must be in the highest degree pernicious. The testimony

ofMr. Douglass, on this point, is

sustained by a cloud of witnesses, whose veracity is unimpeachable.

"A slaveholder's profession of Christianity is a palpable

imposture. He is a felon of the highest grade. He is a man-stealer.

It is of no importance what you put in the other

scale."Reader! are you with the man-stealers in sympathy and

purpose, or on the side of their down-trodden victims? If with the

former, then are you the foe of God and man. If with the latter,

what are you prepared to do and dare in their behalf? Be faithful,

be vigilant, be untiring in your efforts to break every yoke, and

let the oppressed go free. Come what may—cost what it may—inscribe

on the banner which you unfurl to the breeze, as your religious and

political motto—"NO COMPROMISE WITH SLAVERY! NO UNION WITH

SLAVEHOLDERS!"WM. LLOYD GARRISON BOSTON,

LETTER FROM WENDELL PHILLIPS

My Dear Friend:You remember the old fable of "The Man and the Lion," where

the lion complained that he should not be so misrepresented "when

the lions wrote history."I am glad the time has come when the "lions write history."

We have been left long enough to gather the character of slavery

from the involuntary evidence of the masters. One might, indeed,

rest sufficiently satisfied with what, it is evident, must be, in

general, the results of such a relation, without seeking farther to

find whether they have followed in every instance. Indeed, those

who stare at the half-peck of corn a week, and love to count the

lashes on the slave's back, are seldom the "stuff" out of which

reformers and abolitionists are to be made. I remember that, in

1838, many were waiting for the results of the West India

experiment, before they could come into our ranks. Those "results"

have come long ago; but, alas! few of that number have come with

them, as converts. A man must be disposed to judge of emancipation

by other tests than whether it has increased the produce of

sugar,—and to hate slavery for other reasons than because it

starves men and whips women,—before he is ready to lay the first

stone of his anti-slavery life.I was glad to learn, in your story, how early the most

neglected of God's children waken to a sense of their rights, and

of the injustice done them. Experience is a keen teacher; and long

before you had mastered your A B C, or knew where the "white sails"

of the Chesapeake were bound, you began, I see, to gauge the

wretchedness of the slave, not by his hunger and want, not by his

lashes and toil, but by the cruel and blighting death which gathers

over his soul.In connection with this, there is one circumstance which

makes your recollections peculiarly valuable, and renders your

early insight the more remarkable. You come from that part of the

country where we are told slavery appears with its fairest

features. Let us hear, then, what it is at its best estate—gaze on

its bright side, if it has one; and then imagination may task her

powers to add dark lines to the picture, as she travels southward

to that (for the colored man) Valley of the Shadow of Death, where

the Mississippi sweeps along.Again, we have known you long, and can put the most entire

confidence in your truth, candor, and sincerity. Every one who has

heard you speak has felt, and, I am confident, every one who reads

your book will feel, persuaded that you give them a fair specimen

of the whole truth. No one-sided portrait,—no wholesale

complaints,—but strict justice done, whenever individual kindliness

has neutralized, for a moment, the deadly system with which it was

strangely allied. You have been with us, too, some years, and can

fairly compare the twilight of rights, which your race enjoy at the

North, with that "noon of night" under which they labor south of

Mason and Dixon's line. Tell us whether, after all, the half-free

colored man of Massachusetts is worse off than the pampered slave

of the rice swamps!In reading your life, no one can say that we have unfairly

picked out some rare specimens of cruelty. We know that the bitter

drops, which even you have drained from the cup, are no incidental

aggravations, no individual ills, but such as must mingle always

and necessarily in the lot of every slave. They are the essential

ingredients, not the occasional results, of the

system.After all, I shall read your book with trembling for you.

Some years ago, when you were beginning to tell me your real name

and birthplace, you may remember I stopped you, and preferred to

remain ignorant of all. With the exception of a vague description,

so I continued, till the other day, when you read me your memoirs.

I hardly knew, at the time, whether to thank you or not for the

sight of them, when I reflected that it was still dangerous, in

Massachusetts, for honest men to tell their names! They say the

fathers, in 1776, signed the Declaration of Independence with the

halter about their necks. You, too, publish your declaration of

freedom with danger compassing you around. In all the broad lands

which the Constitution of the United States overshadows, there is

no single spot,—however narrow or desolate,—where a fugitive slave

can plant himself and say, "I am safe." The whole armory of

Northern Law has no shield for you. I am free to say that, in your

place, I should throw the MS. into the fire.You, perhaps, may tell your story in safety, endeared as you

are to so many warm hearts by rare gifts, and a still rarer

devotion of them to the service of others. But it will be owing

only to your labors, and the fearless efforts of those who,

trampling the laws and Constitution of the country under their

feet, are determined that they will "hide the outcast," and that

their hearths shall be, spite of the law, an asylum for the

oppressed, if, some time or other, the humblest may stand in our

streets, and bear witness in safety against the cruelties of which

he has been the victim.