1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

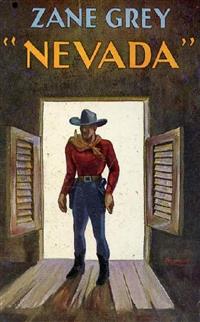

Returning after five years, Tom McComber found that the peaceful little Nevada town hadn't changed much. The Circle-M, the hugh ranch that his father had held through years of bitter conflict, was still intact. One thing, however, was changed. Tom's former wife was going to marry his father! Nevada, the suspenseful sequel to Forlorn River, continues to be one of Zane Grey’s most beloved novels.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Nevada

by Zane Grey

First published in 1926

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Nevada

by

Zane Grey

Chapter One

As his goaded horse plunged into the road, Nevada looked back over his shoulder. The lane he had plowed through the crowd let him see back into the circle where the three men lay prostrate. The blue smoke from his gun was rising slowly, floating away. Ben Ide's face shone white and convulsed in the sunlight.

"So long, Pard!" yelled Nevada, hoarsely, and stood in his stirrups to wave his sombrero high. That, he thought, was farewell forever to this friend who had saved and succored and uplifted him, whom he loved better than a brother.

Then Nevada faced the yellow road down which his horse was racing, and the grim and terrible mood returned to smother the heart–swelling emotion which had momentarily broken it.

There was something familiar and mocking about this precipitate flight on a swift horse, headed for the sage and the dark mountains. How often had he felt the wind sting his face on a run for his life! But it was not fear now, nor love of life, that made him a fugitive.

The last gate of the ranch was open, and Nevada flashed through it to turn off the road into the sage and go flying down the trail along the shore of the lake. The green water blurred on one side of him and the gray sage on the other. Even the winding trail was indistinct to eyes that still saw red. There was no need now for this breakneck ride. To be sure, the officers of the law would eventually get on his track, as they had been for years; but thought of them scarcely lingered a moment in his consciousness.

The action of a swift and powerful horse seemed to be necessary to the whirling of his mind. Thoughts, feelings, sensations regurgitated around that familiar cold and horrible sickness of soul which had always followed the spilling of human blood and which this time came back worse than ever.

The fierce running of the horse along the levels, around the bends of the trail, leaping washes, plunging up and down the gullies, brought into tense play all Nevada's muscular force. It seemed like a mad race away from himself. Burning and wet all over, he gradually surrendered to physical exertion.

Five miles brought horse and rider far around to the other side of the lake. Here the trail wound down upon the soft sand, where the horse slowed from run to trot, and along the edge of the lake, where the midday sun had thawed the ice. Nevada had a break in his strained mood. He saw the deep hoof tracks of horses along the shore, and the long cuts and scars on the ice, where he and Ben and the freed outlaws had run that grand wild stallion, California Red, to his last plunge and fall. Nevada could not help but think, as he passed that place, and thrill as he remembered the strange lucky catch of the wild horse Ben Ide loved so well. What a trick for fortune to play! How mad Ben had been—to bargain with the rustlers they had captured—to trade their freedom for the aid they gave in running down the red stallion! Yet mad as that act had been, Nevada could only love Ben the more. Ben was the true wild–horse hunter.

Nevada reached the bluff where Forlorn River lost itself in the lake, and climbed the sloping trail to the clump of trees and the cabin where he and Ben had lived in lonely happiness. Ben, the outcast son of a rich rancher of Tule Lake—and he, the wandering, fugitive, crippled gunman, whom Ben had taken in with only one question.

"Where you from?" Ben had asked.

"Nevada," had been the reply. And that had been the only name by which Ben had ever known him.

It was all over now. Nevada dismounted from his wet and heaving horse. "Wal, Baldy," he said, throwing the bridle, "heah we are. Reckon the runnin's aboot over." And he sank heavily upon the porch step, pushed his sombrero back to run a hand through his wet hair, smoothing it away from his heated brow. He gazed across the lake toward the dots on the far gray slope—the dots that were the cabins and barns of the Blaine ranch. With the wrench which shook him then, the last of that icy nausea—that cold grip from bowels to heart—released its cramping hold and yielded to the softening human element in Nevada. It would have been better for him if that sinister fixity of mind had not passed away, because with its passing came a slow–growing agony.

"Reckon I cain't set heah mopin' like an owl," soliloquized Nevada, getting up. "Shore, the thing's done. An' I wouldn't have it otherwise…. Dear old Ben!"

But he could not just yet enter the cabin where he had learned the glory of friendship.

"He was the only pard I ever had, except a hoss or two…. Wal, Ben's name is cleared now—thank God. Old Amos Ide knows the truth now an' he'll have to beg forgiveness of Ben. Gosh! how good that'll be! But Ben, he'll never rub it in on the old gent. He'll be soft an' easy…. Hart Blaine will know, too, an' he'll have to come round to the boy. They'll all have to crawl for callin' Ben a rustler…. Ben will marry Ina now—an' he'll be rich. He's got California Red, too, an' he'll be happy."

From the lake Nevada gazed away across Forlorn River, over the gray sage hills, so expressive of solitude, over the black ranges toward the back country, the wilderness whence he had come and to which he must return. To the hard life, the scant fare, the sordid intimacy of crooked men and women, to the border of Nevada, where he had a bad name, where he could never sleep in safety, or wear a glove on his gun–hand! But at that moment Nevada had not one regret. He was sustained and exalted by the splendid consciousness that he had paid his debt to his friend. He had saved Ben from prison, cleared his name of infamy, given him back to Ina Blaine, and killed his enemies. Whatever had been the evil of Nevada's life before he met Ben, whatever might be the loneliness and bitterness of the future, neither could change or mitigate the sweetness and glory of the service he had rendered.

Nevada went into the cabin. He had expected to find it as always, clean and neat and comfortable. The room, however, was in rude disorder. It had been ransacked by violent hands. The pseudo–sheriffs, who had come at the beck of Less Setter to arrest Ben, had not hesitated to stoop to thievery. They had evidently searched the cabin for money, or anything of value.

Nevada gazed ponderingly around on this disorder.

"Wal," he muttered, grimly, "I reckon Less Setter won't be rammin' around heah any more—or any other place short of hell!"

With that remark Nevada strode out and down the path to the corrals. There were horses in at the watering trough. He caught one, and securing packsaddle and packs, he returned to the cabin. Here he hurriedly gathered his belongings and food, blankets, ammunition. Then mounting his horse he drove the pack animal ahead of him, and rode down to the shallow ford across Forlorn River.

"Shore, Ben will always keep this ranch as we had it," he mused. "An' he'll come heah often."

Hot tears fell from Nevada's eyes, the first he had shed since his orphaned boyhood, so dim and far away. It was no use to turn his eyes again to the little gray cabin half hidden among the trees, for he could not see. But as he rode up the river his tears dried, and he saw the pasture where the horses he had owned with Ben raised their heads to look and to neigh. From a ridge top a mile or more up the lonely river, Nevada gazed back at the cabin for the last time. Something surer than his intelligence told him that he would never see it again. The moment was poignant. It opened a door into his mind, which let in the fact he had so stubbornly resisted—that when he bade good–by to the little cabin it was not only good–by to it and to his friend, but to the most precious of all that had ever entered his life—Hettie Ide.

Nevada made that farewell, and then rode on, locked in thought which took no notice of the miles and the hours. Sunset brought him to an awareness of the proximity of night and the need of suitable camp for himself and his animals. While crossing the river, now a shallow rod–wide stream, he let the horses drink. On the other side he dismounted to fill his waterbag and canteen. Then he rode away from the river and trail in search of a secluded spot. He knew the country, and before long reached a valley up which he traveled some distance. There was no water and therefore an absence of trails. Riding through a thicket of slender oaks, which crossed the narrowing valley, he halted in a grassy dell to make his camp.

His well–trained horses would not stray beyond the grass plot, and there was little chance of the eyes of riders seeing his camp fire. How strange to be alone again! Yet such loneliness had been a greater part of his life before he chanced upon Ben Ide. From time to time Nevada's hands fell idle and he stood or knelt motionless while thought of the past held him. In spite of this restlessness of spirit he was hungry and ate heartily. By the time his few camp chores were done, night had fallen, pitch black, without any stars.

Then came the hour he dreaded—that hour at the camp fire when the silence and solitude fell oppressively upon him. Always in his lonely travels this had been so, but now they were vastly greater and stranger. Something incomprehensible had changed him, sharpened his intelligence, augmented his emotions. Something tremendous had entered his life. He felt it now.

The night was cold and still. A few lonesome insects that had so far escaped the frost hummed sadly. He heard the melancholy wail of coyotes. There were no other sounds. The wind had not risen.

Nevada sat cross–legged, like an Indian, before his camp fire. It was small, but warm. The short pieces of dead hard oak burned red, like coal. Nevada spread his palms to the heat, an old habit of comfort and pleasure. He dreaded to go to the bed he had made, for he would fall asleep at once, then awake during the night, to lie in the loneliness and stillness. The longer he stayed awake the shorter that vigil in the after hours of the night. Besides, the camp fire was a companion. It glowed and sparkled. It was something alive that wanted to cheer him.

The moment came when Hettie Ide's face appeared clearly in the gold and red embers. It shone there, her youthful face crowned by fair hair, with its earnest gray eyes and firm sweet lips. It looked more mature than the face of a sixteen–year–old girl—brave and strong and enduring.

Strange and terrible to recall—Nevada had kissed those sweet lips and had been kissed by them! That face had lain upon his breast and the fair hair had caressed his cheek. They would haunt him now, always, down the trails of the future, shining from every camp fire.

"Hettie—Hettie," he whispered, brokenly, "you're only a kid an' shore you'll forget. I'm glad Ben never knew aboot us. It'll all come out now after my gunplay of to–day. An' you an' Ben will know I am Jim Lacy!… Oh, if only I could have kept it secret, so you'd never have known I was bad! An', oh—there'll never be any one to tell you I cain't be bad no more!"

Thus Nevada mourned to himself while the shadow face in the fire softened and glowed with sweetness and understanding. It was an hour when Nevada's love mounted to the greatness of sacrifice, when he cast forever from him any hope of possession, when he realized all that remained were the glory and the dream, and the changed soul which must be true to the girl who had loved him and believed in him.

Beside that first camp fire Nevada's courage failed. He had never, until now, realized the significance of that moment when Hettie and he, without knowing how it had come to pass, found themselves in each other's arms. What might have been! But that, too, had only been a dream. Still, Nevada knew he had dreamed it, believed in it, surrendered to it. And some day he might have buried the past, even his name, and grasped the happiness Hettie's arms had promised. Ben would have joyfully accepted him as a brother. But in hiding his real name, in living this character Nevada, could he have been true to the soul Ben and Hettie had uplifted in him? Nevada realized that he could no longer have lived a lie. And though he would not have cared so much about Ben, he had not wanted Hettie to learn that he had been Jim Lacy, notorious from Lineville across the desert wastes of Nevada clear to Tombstone.

"Reckon it's better so," muttered Nevada to the listening camp fire. "If only Hettie never learns aboot the real me!"

The loss of Hettie was insupportable. He had been happy without realizing it. On the steps of friendship and love and faith he had climbed out of hell. He had been transformed. Never could he go back, never minimize the bloody act through which he had saved his friend from the treachery of a ruthless and evil man. That act, as well, had saved the Blaines and the Ides from ruin, and no doubt Ina and Hettie from worse. For that crafty devil, Setter, had laid his plans well.

Nevada bowed his bare head over his camp fire, and a hard sob racked him.

"Shore—it's losin' her—that kills me!" he ground out between his teeth. "I cain't—bear it."

* * * * *

When he crawled into his blankets at midnight it was only because the conflict within him had exhausted his strength. Sleep mercifully brought him oblivion. But with the cold dawn his ordeal returned, and the knowledge that it would always abide with him. The agony was that he could not be happy without Hettie Ide's love—without sight of her, without her smile, her touch. He wanted to seek some hidden covert, like a crippled animal, and die. He wanted to plunge into the old raw life of the border, dealing death and meeting death among those lawless men who had ruined him.

But he could not make an end to it all, in any way. The infernal paradox was that in thought of Ben's happiness, which he had made, there was an ecstasy as great as the agony of his own loss. Furthermore, Hettie's love, her embraces, her faith had lifted him to some incredible height and fettered him there, forever to fight for the something she had created in himself. He owed himself a debt greater than that which he had owed Ben. Not a debt to love, but to faith! Hettie had made him believe in himself—in that newborn self which seemed now so all–compelling and so inscrutable.

"Baldy, I've shore got a fight on my hands," he said to his horse, as he threw on the saddle. "We've got to hit the back trails. We've got to eat an' sleep an' find some place where it's safe to hide. Maybe, after a long while, we can cross over the desert to Arizona an' find honest work. But, by Heaven! if I have to hide all my life, an' be Jim Lacy to the bloody end, I'll be true to this thing in my heart—to the name Ben Ide gave me—Nevada—the name an' the man Hettie Ide believed in!"

* * * * *

Nevada traveled far that day, winding along the cattle trails up the valleys and over the passes. He began to get into high country, into the cedars and piñons. Far above him the black timber belted the mountains, and above that gleamed the snow line. He avoided the few cattle ranches which nestled in the larger grass valleys. Well–trodden trails did not know the imprint of his tracks that day; and dusk found him camped in a lonely gulch, with high walls and grassy floor, where a murmuring stream made music.

Endless had been the hours and miles of the long day's ride. Camp was welcome to weary man and horses. The mourn of a wolf, terrible in its haunting prolonged sadness and wildness, greeted Nevada by his camp fire. A lone gray wolf hungering for a mate! The cry found an echo in the cry of Nevada's heart. He too was a lone wolf, one to whom nature had been even more cruel.

And once again a sweet face with gray questioning eyes gleamed and glowed and changed in the white–red heart of the camp fire.

On the following day Nevada climbed the divide that separated the sage and forest country from the desert beyond. It was a low wide pass through the range, easily surmountable on horseback, though the trail was winding and rough. The absence of cattle tracks brought a grim smile to Nevada's face. He knew why there were none here, and where, to the south through the rocky fastnesses of another and very rough pass, there were many. But few ranchers who bought or traded cattle ever crossed that divide.

From a grassy saddle, where autumn wild flowers still bloomed brightly, he gazed down the long uneven slope of the range, to the canyoned and cedared strip of California, and on to the border of Nevada, bleak, wild, and magnificent. The gray–and–yellow desert stretched away illimitably, with vast expanse of hazy levels and endless barren ranges. The prospect in some sense resembled Nevada's future, as he imagined it.

As he gazed mournfully out over this tremendous and monotonous wasteland a powerful antagonism to its nature and meaning swept over him. How he had learned to love the fragrant sage country behind him! But this desert was hard, bitter, cruel, like the men it developed. He hated to go back to it. Could he not find a refuge somewhere else—surely in far–off sunny Arizona? Yet strange to feel, this wild Nevada called to something deep in him, something raw and deadly and defiant.

"Reckon I'll hide out awhile in some canyon," he reflected.

Then he began the descent from the divide, and soon the great hollow and the upheaval of land beyond were lost to his sight. The trail zigzagged down and up, under the brushy banks, through defiles of weathered rock, over cedar ridges, on and on down out of the heights.

Before Nevada reached the end of that long mountain slope he heard the dreamy hum of a tumbling stream, and turning off the trail he picked his way over the roughest of ground to the rim of a shallow canyon, whence had come the sound of falling water. He walked, leading his horses for a mile or more before he found a break in the canyon wall where he could get down.

Here indeed was a lonely retreat. Grass and wood were abundant, and tracks of deer and other game assured him he could kill meat. A narrow sheltered reach of the canyon, where the cottonwood trees still were green and gold and the grass grew rich along the stream, appeared a most desirable place to camp.

So he unpacked his horses, leisurely and ponderingly, as if time were naught, and set about making a habitation in the wilds. From earliest boyhood this kind of work had possessed infinite charm. No time in his life had he needed solitude as now.

Nevada did not count the days or nights. These passed as in a dream. He roamed up and down the canyon with his rifle, though he used it only when he needed meat. He spent hours sitting in sunny spots, absorbed in memory. His horses grew fat and lazy. Days passed into weeks. The cottonwoods shed their leaves to spread a golden carpet underneath. The nights grew cold and the wind moaned in the trees.

The time came when solitude seemed no longer endurable. Nevada knew that if he lingered there he would go mad. For there encroached upon his dream of Hettie Ide and Ben, and that one short beautiful and ennobling period of his life, a strange dark mood in which the men he had killed came back to him. Nevada had experienced this before. The only cure was drink, work, action, a mingling with humankind, the sound of voices. Even a community of the most evil of men and women could save him from that haunting shadow in his mind.

Somberly he thought it all out. Though he had deemed he was self–sufficient, he found his limitations. He could no longer dwell alone in this utter solitude, starving his body, falling day by day deeper into melancholy and mental aberration. There seemed to be relief even in the thought of old associations. Yet Nevada shuddered in his soul at the inevitable which would force him back into the old life.

"Reckon now it's aboot time for me to declare myself," he muttered. "I cain't lie to myself, any more than I could to Hettie. I've changed. I change every day. Shore I don't know myself. An' this damned life I face staggers me. What am I goin' to do? I say find honest work somewhere far off. Arizona, perhaps, where I'd be least known. That's what Hettie would expect of me. She'd have faith I'd do it…. An', by Gawd! I will do it!…But for her sake an' Ben's, never mindin' my own, I've got to hole up till that last gun–throwin' of mine is forgotten. If I were found an' recognized as Jim Lacy it'd be bad. An' if anyone did, it'd throw the light on some things I'd rather die than have Hettie Ide know."

Chapter Two

It was a cold, bleak November day when Nevada rode into Lineville. Dust and leaves whipped up with the wind. Columns of blue wood smoke curled from the shacks and huts and houses of the straggling hamlet. Part of these habitations, those on one side of the road, lay in California, and those on the other belonged to Nevada. Many a bullet had been fired from one state to kill a man in the other.

Lineville had been a mining town of some pretensions during the early days of the gold rush. Deserted and weathered shacks were mute reminders of more populous times. High on the bleak drab foothill stood the ruins of an ore mill, with long chute and rusted pipes running down to the stream. Black holes in the cliffs opposite attested to bygone activity of prospectors. Gold was still to be mined in the rugged hills, though only in scant quantity. Prospectors arrived in Lineville, wandered around for a season, then left on their endless search, while other prospectors came. When Nevada had last been there it was possible to find a few honest men and women, but the percentage in the three hundred population was small.

Nevada halted before a gray cabin set well back in a large plot of ground just inside the limits of the town. The place had not changed. A brown swayback horse, with the wind ruffling his deep fuzzy coat, huddled in the lee of an old squat barn. Nevada knew the horse. Corrals and sheds stood farther back at the foot of the rocky slope. Briers and brush surrounded a garden where some late greens showed bright against the red dug–up soil. Nevada remembered the rudely painted sign that had been nailed slantwise on the gate–post. Lodgings.

Dismounting, Nevada left his horses and entered, to go round to the back of the cabin. A wide low porch had been stacked to the roof with cut stove wood, handy to the door. Nevada hesitated a moment, then knocked. He heard a bustling inside, brisk footsteps, after which the door was opened by a buxom matron, with ruddy face, big frank eyes, and hair beginning to turn gray.

"Howdy, Mrs. Wood!" he greeted her.

The woman stared, then burst out: "Well, for goodness' sake, if it ain't Jim Lacy!"

"I reckon. Are you goin' to ask me in? I'm aboot froze."

"Jim, you know you never had to ask to come in my house," she replied, and drew him into a cozy little kitchen where a hot stove and the pleasant odor of baking bread appealed powerfully to Nevada.

"Thanks. I'm glad to hear that. Shore seems like home to me. I've been layin' out in the cold an' starvin' for a long time."

"Son, you look it," she returned, nodding her head disapprovingly at him. "Never saw you like this. Jim, you used to be a handsome lad. How lanky you are! An' you're as bushy haired as a miner…. What're you been up to?"

"Wal, Mrs. Wood," he drawled, coolly, "shore you've heard aboot me lately?" And his gaze studied her face. Much might depend upon her reply, but she gave no sign.

"Nary a word, Jim. Not lately or ever since you left."

"No? Wal, I am surprised, an' glad, too," replied Nevada, smiling his relief. "Reckon you couldn't give me a job? Helpin' around, like I used to, for my board."

"Jim, I jest could, an' I will," she declared. "You won't have to sleep in the barn, either."

"Now, I'm doggone lucky, Mrs. Wood," replied Nevada, gratefully.

"Humph! I don't know about that, Jim. Comin' back to Lineville can't be lucky…. Ah, boy, I'd hoped if you was alive you'd turned over a new leaf."

"It was good of you to think of me kind like that," he said, moving away from the warm stove. "I'll go out an' look after my pack an' horses."

"Fetch your pack right in. An' I'll not forget you're starved."

Nevada went out thoughtfully, and slowly led his horses out to the barn. There, while he unpacked, his mind dwelt on the singular effect that Mrs. Wood's words had upon him. Perhaps speech from anyone in Lineville would have affected him similarly. He had been brought back by word of mouth to actualities. This kindly woman had hoped he would never return. He took so long about caring for his horses and unpacking part of his outfit that presently Mrs. Wood called him. Then shouldering his bed–roll and carrying a small pack, he returned to the kitchen. She had a hot meal prepared. Nevada indeed showed his need of good and wholesome food.

"You poor boy!" she said once, sadly and curiously. But she did not ask any questions.

Nevada ate until he was ashamed of himself. "Shore I know what to call myself. But it tasted so good."

"Ahuh. Well, Jim, you take some hot water an' shave your woolly face," she returned. "You can have the end room, right off the hall. There's a stove an' a box of wood."

Nevada carried his pack into the room designated, then returned for the hot water, soap, and towel. Perhaps it was the dim and scarred mirror that gave his face such an unsightly appearance. He was to find out presently that shaving and clean clothes and a vastly improved appearance meant nothing to him, because Hettie had gone out of his life forever. What did he care how he looked? Yet he remembered with a twinge that she would care. When an hour later he strode into the kitchen to confront Mrs. Wood, she studied him with eyes as speculative as kind.

"Jim, I notice your gun has the same old swing, low down. Now that's queer, ain't it?" she said, ironically.

"Wal, it shore feels queer," he responded. "For, honest, Mrs. Wood, I haven't packed it at all for a long time."

"An' you haven't been lookin' at red liquor, either?" she went on.

"Reckon not."

"An' you haven't been lookin' at women, either?"

"Gosh! no. I always was scared of them," he laughed, easily. But he could not deceive her.

"Boy, somethin' has happened to you," she declared, seriously. "You're older. Your eyes aren't like daggers any more. They've got shadows…. Jim, I once saw Billy the Kid in New Mexico. You used to look like him, not in face or body or walk, but jest in some way, some look I can't describe. But now it's gone."

"Ahuh. Wal, I don't know whether or not you're complimentin' me," drawled Nevada. "Billy the Kid was a pretty wild hombre, wasn't he?"

"Humph! You'd have thought so if you'd gone through that Lincoln County cattle war with me an' my husband. They killed three hundred men, and my Jack was one of them."

"Lincoln County war?" mused Nevada. "Shore I've heard of that, too. An' how many of the three hundred did Billy the Kid kill?"

"Lord only knows," she returned, fervently. "Billy had twenty–one men to his gun before the war, an' that wasn't countin' Greasers or Injuns. They said he was death on them…. Yes, Jim, you had the look of Billy, an' if you'd kept on you'd been another like him. But somethin' has happened to you. I ain't inquisitive, but have you lost your nerve? Gunmen do that sometimes, you know."

"Shore, that's it, Mrs. Wood. I've no more nerve than a chicken," drawled Nevada, with all his old easy coolness. It was good for him to hear her voice and to exercise his own.

"Shoo! An' I'll bet that's all you tell me about yourself," she said. "Jim Lacy, you left here a boy an' you've come back a man. Wonder what Lize Teller will think of you now. She was moony about you, the hussy!"

"Lize Teller," echoed Nevada, ponderingly. "Shore I remember now. Is she heah?"

"She about bosses Lineville, Jim. She doesn't live with my humble self any more, but hangs out at the Gold Mine."

Nevada found a seat on a low bench between the stove and the corner, a place that had been a favorite with him and into which he dropped instinctively, and settled himself for a talk. This woman held a unique position in the little border hamlet, in that she possessed the confidence of gamblers, miners, rustlers, everybody. She was a good soul, always ready to help anyone in sickness or trouble. Whatever her life had been in the past—and Nevada guessed it had been one with her outlaw husband—she was an honest and hard–working woman now. In the wild days of his former association with Lineville he had not appreciated her. She probably had some other idler or fugitive like himself doing the very odd jobs about the place that he had applied for. Nevada remembered that her kindliness for him had been sort of motherly, no doubt owing to the fact that he had been the youngest of the notorious characters of Lineville.

"Lize married yet?" began Nevada, casually.

"No indeed, an' she never will be now," replied Mrs. Wood, forcibly. "She had her chance, a decent cattleman named Holder, from Eureka. Reckon he knew he was buyin' stolen cattle. But for all that he was a mighty fine sort for Lineville. Much too good for that black–eyed wench. She was taken with him, too. Her one chance to get away from Lineville! Then Cash Burridge rode in one day—after a long absence. 'Most as long as yours. Cash had been in somethin' big, south somewhere. An' he come back to lie low an' gamble. He had plenty of money, as usual. Lost it, as usual. Lize was clerk at the Gold Mine. She got thick with Cash. He an' Holder had a mix–up over the girl, an' that settled her. Maybe I didn't give her a piece of my mind. But I might as well have shouted to the hills. She went from bad to worse. You'll see."

"Cash Burridge back," rejoined Nevada, somberly, and he dropped his head. That name had power to make him want to hide the sudden fire in his eyes. "Reckon I'd plumb forgot Cash."

"Ha! Ha! Yes, you did, Jim Lacy," replied the woman, knowingly. "No one would ever forget Cash, much less you…. Dear me, I hope you an' he don't meet again."

"Wal, of course we'll meet," said Nevada. "I cain't hang round your kitchen all the while, much as I like it."

"Jim, I didn't mean meet him on the street, or in the store, or anywhere. You know what I meant."

"Don't worry, Mother Wood. Reckon Cash an' I won't clash. Because I'm not lookin' for trouble."

"You never did, my boy, I'll swear to that. But you never run from it. An' you know Cash Burridge. He's bad medicine sober, an' hell when he's drunk."

"Ahuh, I reckon, now you remind me. Has Cash been up to his old tricks lately?"

"I haven't heard much, Jim," she returned, thoughtfully. "Mostly just Lineville gossip. No truth in it, likely."

Nevada knew it would do no good to press her further in this direction, which reticence was proof that Cash Burridge had been adding to his reputation one way or another. Nevada had curious reaction—a scorn for his own strange, vague eagerness to know. Old submerged or forgotten feelings were regurgitating in him. A slow heat ran along his veins.

"Lineville shore looks daid," he said, tentatively.

"It is dead, Jim. But you know it's comin' on winter. An' this Lineville outfit is like a lot of groundhogs. They hole–up when the snow flies. There's more travel along the road than ever before. Three stages a week now, an' lots of people stop here for a night. I get a good many; been busy all summer an' fall."

"Travel on the road? Wal, that's a new one for Lineville. Prospectors always came along. But travel. What you mean, Mother Wood?"

"Jim, where have you been for so long?" she asked, curiously. "Sure you must have been buried somewhere. There's a new minin' town—Salisbar. An' travel from north has been comin' through here, in spite of the awful road."

"Salisbar? Never heard aboot it. An' stagecoaches—goin' through Lineville! By golly!"

"Jim, there's been only couple of hold–ups. None of this outfit, though. We hear the stage line will stop runnin' soon, till spring."

"You mentioned aboot a cattleman named Holder buyin' heah since I've been away. Shore he's not the only one?"

"No. But cattle deals have been low this summer. Last bunch of cattle come over in June."

"Wal, you don't say! Lineville is daid, shore enough."

"Jim, that sort of thing has got to stop sometime, even if it is only a lot of two–bit rustlin'."

"Two–bit? Ha! Ha!"

"Jim, I've seen thousands of longhorns rustled in my day."

"Ahuh! Reckon you have, I'm sorry to say," responded Nevada, looking up at her ruddy face again. "Shore you never took me for a rustler, did you, Mother?"

"Goodness, no! You was only a gun–packin' kid, run off the ranges. But, Jim, you'll fall into it some day, sure as shootin'. You'll be in bad company at the wrong time. Now I'm from Texas an' I always loved a good clean hard–shootin' gunman, like Jack was. There wasn't nothin' crooked about Jack for years an' years. But he fell into it. An' so will you, Jim. I want you to go so far away from Lineville that you can't never come back."

"I'll go in the spring. Shore I'm not hankerin' for the grub–line ride these next few months."

"Fine. That's a promise, my boy. I'll not let you forget it. An' meanwhile it'll be jest as well for you to be snug an' hid right here. Till spring, huh?"

"Mother Wood, you said you wasn't inquisitive," laughed Nevada, parrying her question. Then he grew serious. "When was Hall heah last?"

"In June, with the last cattle that come over the divide. An', Jim, the right queer fact is he's never been back."

"Wal, I reckon that's not so queer to me. Maybe he has shook the dust of Lineville. He rode in heah sudden, so I was told. An' why not ride off that way? To new pastures, Mother Wood?"

"No reason a–tall," she said, reflectively. "Only I jest don't feel that way about Hall."

"An' that high–flyin' Less Setter from the Snake River country. Did he ever come again?"

"No. That time you clashed with Setter was the only time he ever hit Lineville. No wonder! They said you'd kill him if he did. I remember, Jim, how that night after the row you talked a lot. It was the drink. You'd had trouble with Setter before you come to these parts. I never told it, but I remember."

"Wal, Mother, I came from the Snake River country, too," replied Nevada, with slow dark smile.

"It was said here that Less Setter was too big a man to fiddle around Lineville," returned the woman, passing by Nevada's cryptic remark, though it was not lost upon her. "Hall said Setter had many brandin' irons in the fire. His game, though, was to wheedle rich cattlemen an' ranchers into speculations. He was a cunnin' swindler, low–down enough for any deal. An' he had a weakness for women. If nothin' else ever was his downfall, that sure would be. He tried to take Lize Teller away with him."

"Wal, you don't say!" ejaculated Nevada, trying to affect interest and surprise that were impossible for him to feel. Again he casually averted his face to hide his eyes. For that cold, sickening something had shuddered through his soul. Less Setter would never have a weakness for women again. He would never weave his evil machinations around Ben and Hettie Ide, or anyone else, for he and two of his arch conspirators had lain dead there in the courtyard before Hart Blaine's cabins on the shores of Wild Goose Lake Ranch. Dead by Nevada's hand! That was the deed that had saved Ben Ide, and Hettie, too. It seemed long past, yet how vivid the memory! The crowd that had melted before his charging horse! The terror of the stricken Setter! Revenge and retribution and death! Those villains lay prone under the drifting gunsmoke, before the onlookers. Nevada saw himself leap back to the saddle and spur his horse away. One look back! "So long, pard!" One look at Ben's white, convulsed face, which would abide with him forever.

"Lineville has had its day," the woman was saying, as if with satisfaction at the fact. "Setter saw that, if he ever had any idea of operatin' here. Hall saw it, too, for he's never come back. Cash Burridge knows it. He has been away to the south—Arizona somewhere—lookin' up a place where outside travel hasn't struck. He'll leave when the snow melts next spring, an' he'll not go alone. Then decent people won't be afraid to walk down to the store."

"Good luck for Lineville, but bad for Arizona somewhere," returned Nevada, dryly. "Shore, I feel sorry for the ranchers over there."

"Humph! I don't know. There are wilder outfits in Arizona than this country ever saw," rejoined the woman, contemptuously. "Take that Texas gang in Pleasant Valley, an' the Hash Knife outfit on the Tonto Rim, not to speak of the Mexican border. Cash Burridge isn't the caliber to last long in Arizona. Waters an' Blink Miller are tough nuts to crack, I'll admit. I suppose Hardy Rue will trail after Burridge, an' of course that loud–mouthed Link Cawthorne. But there's only one of the whole Lineville outfit that could ever last in Arizona. An' you know who he is, Jim Lacy."

"Wal, now, Mother, I shore haven't the least idee," drawled Nevada.

"Go 'long with you," she replied, almost with affection. "But, Jim, I'd rather think of you gettin' away from this life than lastin' out the whole crew. I've heard my husband say that gunmen get a mind disease. The gunman is obsessed to kill. An' if another great killer looms on the horizon the disease forces him to go out to meet this one. Jest to see if he can kill him! Isn't that terrible? But it was so in Texas in the old frontier days there."

"It shore is terrible," responded Nevada, gloomily. "I can understand a man learnin' to throw a gun quick for self–defense. Shore that was my own excuse. But for the sake of killin'! Reckon I don't know what to call that."

During the hour Mrs. Wood, who had a gift for learning and dispensing information of all sorts, acquainted Nevada with all that had happened in Lineville since his departure. She did not confine herself to the affairs of the outlaw element who made of Lineville a rendezvous. The few children Nevada had known and played with, the new babies that had arrived in the interim, the addition of several more families to the community, the talk of having a school, and the possibilities of a post office eventually—these things she discussed in detail, with a pleasure and satisfaction that had been absent in her gossip about Lineville's hard characters.

But it was that gossip which lingered in Nevada's mind. Later when he went into his little room he performed an act almost unconsciously. It was an act he had repeated a thousand times in such privacy as was his on the moment, but not of late. The act of drawing his gun! There it was, as if by magic, level, low down in his clutching hand. Sight of it so gave Nevada a grim surprise. How thoughtlessly and naturally the fact had come to pass! And Nevada pondered over the singular action. Why had he done that? What was it significant of? He sheathed the long blue gun.

"Reckon Mrs. Wood's talk aboot Cawthorne an' the rest of that outfit accounts for me throwin' my gun," he muttered to himself. "Funny…. No—not so damn funny, after all."

He had returned to an environment where proficiency with a gun was the law. Self–preservation was the only law among those lawless men with whom misfortune had thrown him. He could not avoid them without incurring their hatred and distrust. He must mingle with them as in the past, though it seemed his whole nature had changed. And mingling with these outlaws was never free from risk. The unexpected always happened. There were always newcomers, always drunken ruffians, always some would–be killer like Cawthorne, who yearned for fame among his evil kind. There must now always be the chance of some friend or ally of Setter, who would draw on him at sight. Lastly, owing to the reputation he had attained and hated, there was always the possibility of meeting such a gunman as Mrs. Wood had spoken of—that strange product of frontier life, the victim of his own blood lust, who would want to kill him solely because of his reputation.

Nevada was not in love with life, yet he felt a tremendous antagonism toward men who would wantonly destroy him.

"Reckon I'd better forget my dreamin' heah," he soliloquized. "An' when I'm out be like I used to be. Shore it goes against the grain. I'm two men in one—Nevada an' Jim Lacy…. Reckon Jim better take a hunch."

Whereupon he deliberately set about ascertaining just how much of his old incomparable swiftness on the draw remained with him after the long lack of exercise. During more than one period of his career he had practiced drawing his gun until he had worn the skin of his hand to the quick, and then to callousness. The thing had become a habit for his private hours, wherever he might be.

"Slower'n molasses, as Ben used to say aboot me," he muttered. "But I've the feel, an' I can get it all back."

The leather holster on his belt was hard and stiff. He oiled it and worked it soft with strong hands. The little room, which had only one window, began to grow dark as the short afternoon waned.

* * * * *

It was still daylight, however, when Nevada went out, to walk leisurely down the road into town. How well he remembered the wide bare street, with its lines of deserted and old buildings, many falling to ruin, and the high board fronts where the painted signs had been so obliterated by weathering that they were no longer decipherable! He came at length to the narrow block where there were a few horses and vehicles along the hitching–rails, and people passing to and fro. There were several stores and shops, a saloon, and a restaurant, that appeared precisely as they had always been. A Chinaman, standing in a doorway, stared keenly at Nevada. His little black eyes showed recognition. Then Nevada arrived at a corner store, where he entered.

The place had the smell of general merchandise, groceries, and tobacco combined. To Jones' credit, he had never sold liquor. There was a boy clerk waiting on a woman customer, and Jones, a long lanky Westerner, who had seen range days himself.

"Howdy, Mr. Jones!" said Nevada, stepping forward.

"Howdy yourself, stranger!" replied the storekeeper. "You got the best of me."

"Wal, it's a little dark in heah or your eyes are failin'," returned Nevada, with a grin.

Whereupon the other took a stride and bent over to peer into Nevada's face.

"I'm a son–of–a–gun," he declared. "Jim Lacy! Back in Lineville! I've seen fellers come back I liked less."

He shook hands heartily with Nevada. "Where you been, boy? You sure look well an' fine to me."

"Oh, I've been all over, knockin' aboot, lookin' for a job," drawled Nevada, easily.

"An' you come back to Lineville in winter, lookin' for a job?" laughed Jones.

"Shore," drawled Nevada.

"Jim, I'll bet if I offered you work you'd shy like a colt. Fact is, though, I could do it. I'm not doin' so bad here. There's a lumber company cuttin' up in the foothills. It's a long haul to Salisbar, but they pass through here. Heard about Salisbar?"

"Yes. Reckon I'll have to take a look at it. How far away?"

"Eighty miles or so," returned Jones. "Some miners struck it rich, an' that started Salisbar off as a minin' town. But it's growin' otherwise. Besides mineral, there are timber an' water, some good farm land, an' miles of grazin'. All this is wakin' Lineville up. There's business goin' on an' more comin'."

"Shore I'm glad, Mr. Jones," said Nevada. "Lineville has some good people I'd like to see prosper."

From the store Nevada dropped into a couple of places, where he renewed acquaintance with men who were glad to see him; and then he crossed to the other side of the wide street and went down to the Gold Mine. Dark had fallen and lamps were being lighted. The front of the wide two–story structure appeared quite plain and business–like, deceiving to the traveler. It looked like a respectable hotel. But the Gold Mine was a tavern for the outlaw elect, a gambling hell and a drinking dive that could not have been equaled short of the Mexican border.

Nevada turned the corner to take the side entrance, which led into the long dingily–lighted barroom. A half–dozen men stood drinking and talking at the bar. They noted Nevada's entrance, but did not recognize him, nor did he them. The bartender, too, was strange to Nevada. A wide portal, with curtain of strung beads, opened into a larger room, which was almost sumptuously furnished for such a remote settlement as Lineville. The red hangings were new to Nevada, and some of the furniture. He remembered the gaudy and obscene pictures on the wall, and the card and roulette tables, and particularly the large open fireplace, where some billets of wood burned ruddily. Six men sat around one table, and of those whose faces were visible to Nevada he recognized only one, that of a gambler called Ace Black. His cold eyes glinted on Nevada, then returned to his game.

Nevada took the seat on the far side of the fire, where he could see both entrances to the large room. At the moment there was something akin to bitter revolt at the fact of his presence there. Certainly no one had driven him. No logical reason existed for his visiting the Gold Mine. He would never drink again; he had but little money to gamble with, even had he been so inclined; he rather felt repugnance at the thought of seeing Lize Teller, or any other girl likely to come in. But something restless and keen within him accounted for his desire to meet old acquaintances there. Trying to analyze and understand it, Nevada got to the point of dismay. Foremost of all was a significant motive—he did not care to have Cash Burridge or his followers, especially Link Cawthorne, or anyone ever associated with Setter, think he would avoid them. Yet that was exactly what Nevada wanted to do. The mocking thing about it was the certainty that some kind of conflict would surely result. He could not avoid this. Deep in him was a feeling that belied his reluctance. Could it be a rebirth of old recklessness? He would have to fight that as something untrue to Hettie Ide. And as a wave of sweet and bitter emotion went over him, a musical rattling of the beaded–curtain door attracted his attention.

A girl entered. She had a pale face, and very large black eyes that seemed to blaze at Nevada.

Chapter Three

She came slowly toward him, with the undulating movement of her lissome form that he remembered even better than her tragic face. Life had evidently been harsher than ever to Lize Teller.

Nevada rose and, doffing his sombrero, shook hands with her.

"Jim Lacy!" she ejaculated, with stress of feeling that seemed neither regret nor gladness.

"Howdy, Lize!" drawled Nevada. "Reckon you're sort of surprised to see me heah."

"Surprised? Yes. I thought you had more sense," she returned.

"Wal now, Lize, that's not kind of you," he said, somewhat taken back. "An' I reckon I just don't get your hunch."

"Sit down, Jim," she rejoined, and as he complied she seated herself on the arm of his chair and leaned close. "I've been looking for you all afternoon. Lorenzo saw you ride in and stop at Mrs. Wood's."

"Ahuh! Wal, no wonder you wasn't surprised."

"But I am, Jim. Surprised at your nerve and more surprised at the look of you. What's happened? You've improved so I don't know you."

She leaned against him with the old coquetry that was a part of her and which Nevada had once found pleasing, though he had never encouraged it.

"Thanks, Lize. Wal, there was shore room for improvement. Nothin' much happened, except I've been workin' an' I quit the bottle."

"That's a lot, Jim, and I'm downright glad. I'll fall in love with you all over again."

"Please don't, Lize," he laughed. "I've quit throwin' guns, too. An' I reckon it'd be unhealthy for me, if you did."

"Probably will be, boy. You sure have me guessing," she replied, and she smoothed his hair and his scarf, while she gazed at him with deep, burning, inquisitive eyes. "But don't try to lie to me about your gun tricks, sonny. You forget I'm the only one around Lineville who had you figured."

"Lize, I don't know as I remember that," he said, dubiously. He found she embarrassed him less than in former times. He had always feared Lize's overtures. But that dread was gone.

"Jim, you forget easily," she rejoined, with a touch of bitterness. "But God knows there was no reason for you to remember me. It was natural for me to miss you. For you were the only decent man I knew. But you treated me like you were a brother. And that made me hate you."

"Lize, you didn't hate me," he said. "That was temper. Maybe you got a little miffed because you couldn't make a fool of me like you did the others. Shore I cain't believe you'd be mean enough to hate me."

"Jim, you don't know women," she replied, bitterly. "I can do anything…. Where'd you say you'd been—workin'—all this long while?"

"Wal, now, Lize, I don't recollect sayin'," he drawled. "Shore never liked to talk aboot myself. What have you been doin'?"

"Me! Aw, hell! Can't you see? If I live another year I'll be in the street…. I hate this damned life, Jim. But what can I do?…Of course Mrs. Wood told you all she knew about me."

"Wal, she told me—some," replied Nevada, hesitatingly. "Wish I'd been heah when you made such a darn fool of yourself."

"I wish to God you had," she flashed, with terrible passion. "You'd have shot Cash Burridge. He double–crossed me, Jim. Oh, I know I'm no good, but I'm honest. Cash actually made me believe he would marry me. I told Holder I was not a good girl. He seemed willing to take me, anyhow. But Cash told him a lot of vile lies about me, and it fell through…. I'm working here at the Gold Mine now—everything from bookkeeper to bartender."

"Lize, I heah you're thick with Link Cawthorne," said Nevada.

"Bah! You can call it thick, if you like," she returned, scornfully. "But I call it thin. He's a jealous tight–fisted brag. He's as mean as a coyote. I was half drunk, I guess, when I took up with him. And now he thinks he owns me."

"Wal, Lize, wouldn't it be interestin' for me right now—if Link happened in?" drawled Nevada.

"Ha! Ha! More so for me, Jim," she trilled. "I'll give him something to be jealous about. But Link could never be interesting to you. He's a bluff."

"All the same, Lize, if you'll excuse me I'll stand up an' let you have the chair," replied Nevada, coolly, as he extricated himself and arose.

She swore her amaze. "What the devil's come over you, Jim Lacy?" she demanded. "Why, two years ago, if Link Cawthorne had come roaring in here with two guns you'd have laughed and turned your back."

"Two years ago! Lize, I've learned a lot in that long time."

With sudden change of manner and lowering of voice she queried, sharply, "Jim, did you kill Less Setter?"

Nevada had braced himself for anything from this girl, so at the point–blank question he did not betray himself.

"Setter!…Is he daid?"

"Yes, he's daid," she replied, flippantly mimicking his Southern accent. "And a damn good thing…. Jim Lacy, I lay that to you."

"Wal, Lize, I cain't stop the wanderin's of your mind, but you're shore takin' a lot upon yourself," he returned, coldly.

She caught his hand.

"Jim, I didn't mean to offend," she said, hastily. "I remember you were queer about—you know—when you'd had some gunplay."

"Ahuh? Wal, there's no offense. Reckon I'm sort of hurt that you accuse me."