Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

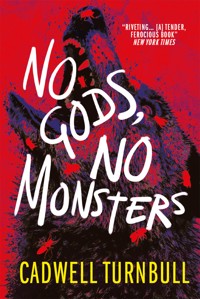

"Riveting... tender, ferocious" ―New York Times Magic and monsters collide in this beautifully crafted, powerful, intense tale told through the voices of a diverse and rich cast of characters. An unforgettable novel from a rising star in fantasy fiction. One October morning, Laina gets the news that her brother has been shot and killed by Boston cops. But what looks like a case of police brutality soon reveals something much stranger. Monsters are real. And they want everyone to know it. As creatures from myth and legend come out of the shadows, seeking safety through visibility, their emergence sets off a chain of seemingly unrelated events. Members of a local werewolf pack are threatened into silence. A professor follows a missing friend's trail of breadcrumbs to a mysterious secret society. And a young boy with unique abilities seeks refuge in a pro-monster organization with secrets of its own. Meanwhile, more people start disappearing, suicides and hate crimes increase, and protests erupt globally, both for and against the monsters. At the center is a mystery no one thinks to ask: Why now? What has frightened the monsters out of the dark? The world will soon find out.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

A Forest of Worlds

1

2

3

The Black Hand

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Emergent Systems of Bees

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

The Fractal Sea

19

20

Home

21

22

23

After The Change

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Bird of Happiness

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

Devotion and Madness

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

Death and Memory

47

48

49

Other Worlds and This One

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

Night Music

58

59

60

61

No Gods, No Monsters

62

63

64

65

The Waking World

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

About the Author

Acknowledgments

PRAISE FOR NO GODS, NO MONSTERS

“Riveting…[A] tender, ferocious book.”NEW YORK TIMES

“This harrowing and lyrical novel combines elements of urban fantasy with biting social commentary.”BUZZFEED

“Big and bold and ambitious, packed with everything we need right now: more heart, more monsters, more cooperative solidarity economies.”SAM J. MILLER, NEBULA AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR OF BLACKFISH CITY AND THE BLADE BETWEEN

“Profound and unsettling in the best way… Sharp, insightful social commentary wrapped up in a tale of the uncanny.”REBECCA ROANHORSE, NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AND HUGO AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR

“Through a series of diverse, rich, and beautifully written voices, Turnbull deftly weaves together a story of supernatural beings, otherworldly entities, magic, and quantum physics… Throughout, we are forced to dwell not only our own humanity, but question who exactly are the monsters we fear? Once I started this novel I could not put it down. You won’t be able to either.”P. DJÈLÍ CLARK, NEBULA AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR OF RING SHOUT

“Magic and monsters roam every corner of this page-turner, but the real star is Cadwell Turnbull’s breath-taking prose. A perfect hymn to otherness and the beauty of the strange… so good it reads like music. Simply masterful.”SYLVAIN NEUVEL, AUTHOR OF THE THEMIS FILES SERIES, THE TEST, AND A HISTORY OF WHAT COMES NEXT

“Structurally ambitious, intricately imagined.”ELIZABETH BEAR, HUGO AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR

“No Gods, No Monsters is both elegant and violent: a cutting, clarifying illumination of humanity in all of its magic and monstrosity.”ISABEL YAP, AUTHOR OF NEVER HAVE I EVER: STORIES

“Beautifully fantastical.”NPR

“Turnbull is a rising star in the science fiction and fantasy world.”THE VERGE

“No Gods, No Monsters is a staggering achievement of literary craftsmanship, a complex juggling act of plot, tension, character interiority, worldbuilding, thought experiment… Cadwell Turnbull’s new novel is absolutely worth your time. Go and grab a copy now, and then join me in the waiting line for whatever he’s got coming next, because I know that will be worth it, too.”TOR.COM

“What makes this book special, what makes it work so damn well, is the way the story is anchored in human complexities… Page by page, scene by scene, Turnbull presents an author’s observations of the real world within the framework of fantasy/horror, executed with subtle, brilliant artistry…”LIGHTSPEED

“You’ll stay up all night bingeing this cosmic political thriller about monster factions battling over the past and future of the multiverse.”ANNALEE NEWITZ, AUTHOR OF THE FUTURE OF ANOTHER TIMELINE AND AUTONOMOUS

“A stunning, enthralling novel.”NEW YORK JOURNAL OF BOOKS

“An epic, meta, Caribbean-inspired fantasy that dives into the dark and shadowy… Multiple viewpoints and protagonists are easy enough to juggle while being compelling, and the inclusion of asexual, trans, and other nonconforming identities and relationships adds a rich layer of truth and reality to the text.”BOOKLIST (STARRED REVIEW)

“This is still a deeply human story, beautifully and compellingly told.”KIRKUS REVIEWS (STARRED REVIEW)

“The expert combination of immersive prose, strong characters, sharp social commentary, and well-woven speculative elements makes for an unforgettable experience. Fantasy fans won’t want to miss this.”PUBLISHERS WEEKLY (STARRED REVIEW)

“Turnbull’s sophomore work puts him at the top of the field of fantasy literary fiction.”LIBRARY JOURNAL (STARRED REVIEW)

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

No Gods, No Monsters

Print edition ISBN: 9781803361512

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803361529

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: October 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Cadwell Turnbull 2022.

Cadwell Turnbull asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To all the ones we’ve lost.

Tanya meets me at our usual spot in Cameron Village, and we sit outside under a patio umbrella, the North Carolina heat cooling to a low simmer in the setting sun. I haven’t told her why it’s so important we meet. We order drinks—me, a Corona because I’m basic as fuck; Tanya, a house cider—and we start talking about work and the adjunct professor struggle. We both know I’m dancing around something. Every few minutes, she looks at me as if to say, “You gonna spill it, or what?” But I just keep on asking questions about her students as if I hadn’t heard about them a thousand times already.

We’re splitting a plate of fries when I tell her.

A french fry rests on her lip at the exact moment I say it. She holds it there with her fingers as if she were about to light up a cigarette. “For the summer?”

I shake my head. “I gave my notice. I won’t be back in the fall.”

Tanya puts the fry all the way into her mouth and chews. Her eyes stay on me the whole time, weighing the information. “So this is permanent, then?”

“Maybe. Don’t know yet.”

“Got a place set up?”

“I’m going to stay with a friend for a while.”

Her eyebrows rise.

“No, nothing like that. Brian. You met him when he came to visit.”

“I remember.”

She is considering something, and I think I know what it is. Only the lime is left in my Corona bottle, but I have the urge to put the smooth glass to my lips out of nervous habit. I have to will myself not to pick the bottle up. “It wasn’t an elaborate plan or anything,” I say. “I decided last week.”

“That’s still a long time to keep it to yourself.” She looks away. “Well, I’m assuming Brian knew, so not just to yourself. Does your mom know?”

“I told her this morning.”

“How’d she take it?”

“Badly. She hasn’t been home since what happened to Cory.”

Tanya knows the whole story, so she lets it lie between us, unmentioned. She places a hand over her lips and stares off for a long time. The action somehow isn’t strange. It’s as if she’s keeping something trapped inside, and we’re both the better for it. Then she gets up, puts a hand on my shoulder, and says she’s going to be right back. She heads for the ladies’ room inside the bar.

She isn’t gone long. While she’s away, the server gives me another Corona. I’ve taken only a couple of sips by the time she comes back and sits down, looking normal—relaxed, even.

“I’m going to miss you,” she says, picking up the conversation as if no time had passed. “Your mom will get over it. Can’t run from the past forever. Who knows? This might be good for the both of you.”

I smile. This might have been what she was going to say, but it feels sifted through, the impurities removed.

We finish our drinks and the plate of fries, talking about Tanya’s chances of becoming an assistant professor. She is feeling good about it. Hopeful. We leave, and I walk with her down the street to her apartment on Ossipee. We hug at the entrance, a little longer and a little tighter than usual.

“We’ll be hanging out again before I leave. You not rid of me yet.”

She lets go. “Was it ever going to happen between us?”

And there it is, low enough that I can pretend I haven’t heard, but my face has already given me away.

“I want you to come up,” she says.

“I don’t think that’s smart.”

“You don’t want to?”

“I do, but—”

“I’m a grown woman,” she chides.

I let her pull me up the stairs. We have another drink and then make love on the couch. It is urgent and without grace. Afterward, we lie together, our limbs tangled, my head resting between her breasts. As we lie there, I listen to her breathing, her heartbeat, the soft human noises of her stomach. I run my fingers down her arm as she strokes the top of my head, her fingertips gently moving with the grain of my fade.

“You should’ve told me sooner,” she says.

“I know. I’m sorry,” I say.

“No, you’re not.”

I don’t try to defend myself.

At some point, I fall asleep on top of her. When I wake up, I am still on the couch, my body stretched under a soft quilt. The smell of fried eggs and bacon wafts from the kitchen. Tanya turns when she hears me stir. “You know you sleep like the dead? I couldn’t even wake you up to get off me.”

I smile and sit up. I can feel the sweat between my thighs, under my pits, and it is uncomfortable. My clothes are on the coffee table, folded neatly.

“I’m making breakfast because I’m hungry,” Tanya adds. “But don’t think I’m going to be serving your ass. You better get up and get some.”

I try putting on my underwear under the quilt but then give up, standing to get it done. Tanya watches, a lustful half smile on her face. “Seriously,” she says, “I could have dressed you myself without you waking up.”

When I’m finished, I come over to the kitchen. I give Tanya a hug but don’t lean in for a kiss. I don’t know what this is going to be, and I want to leave the decision up to her. She slaps me on the butt and points to the cabinet with the plates. I do as I’m told and get one for each of us, then pull some bread from the fridge to make toast. Neither of us broaches the subject of the night before. We eat quietly, and I leave.

I wait a day before texting her, and she takes several hours before hitting me back.

I think I need some time to getover whatever this is. Don’t worry,we cool.

Okay. I really did have a great time.

She doesn’t respond. A month later, when I’m getting on my plane, she sends me a goodbye text.

Be safe. And let me know whenyou land.

I replay that morning with Tanya in my mind as I go through TSA, thinking, if things had gone differently, if we’d been straight with each other sooner, would it have been different between us? I was going home no matter what, so it is a useless exercise. I am tired of visiting St. Thomas only in my dreams.

On the airplane, I sleep like the dead.

I was in my twenties when I read The Unbearable Lightness of Being for the first time. I found it among Cory’s things, worn and yellowed. On its cover, a bowler hat hovers in midair, nothing under it but a dull brick road. For a long time, I felt a personal connection to that image—a hat without a body, an absence. It remains on my bookshelf even after so many years.

Don’t get me wrong. My love for the book isn’t without criticism. This statement in its opening chapter, for example:

Putting it negatively, the myth of eternal return states that a life which disappears once and for all, which does not return, is like a shadow, without weight, dead in advance, and whether it was horrible, beautiful, or sublime, its horror, sublimity, and beauty mean nothing. We need take no more note of it than of a war between two African kingdoms in the fourteenth century, a war that altered nothing in the destiny of the world, even if a hundred thousand blacks perished in excruciating torment.

The we here is meant for all of us. We all agree, right? Wars in African nations and hundreds of thousands of dead Blacks have altered nothing in the world. No great minds perish in Africa. No Caesars or Alexanders. No great mass movements start there to inspire the world. No empires, no utopias. History is never altered by Africa, in this timeline or any other.

The narrator goes on to say that, in contrast, the French Revolution is of note, and the certainty of this statement drips off the page. It’s just facts, people.

The first time I read this shit, I just glided right over the bit about African kingdoms. That first reading, the idea of eternal return stirred something in my mind. It is only briefly referenced in the quote, but the hovering nameless narrator of the novel goes on at length about it. Eternal return is a central theme of the book. The concept is this: The universe and the history of everything are on repeat—a vinyl record spinning forever. Every action happens an infinite number of times, from the big bang to the heat death and back again.

That first time, I misread eternal return as historic recurrence, thinking the narrator meant that world events repeat themselves with minute variation. Both concepts were new to me. I’m not as bright as Cory—I’ve never read Nietzsche—so I don’t catch my mistake until years later. But I read that book at least five times that first year, seeing my brother in it, seeing myself. I return to it now, knowing the difference between the two concepts and believing in both.

Every moment is eternal. Every story carries a bit of the past with it, like a long poem, with stanzas and breaks and refrains. The same is true across timelines, too. If the world is born a billion times in parallel, all those iterations will spring up like a forest of the same wood, repeating themselves up into their leaves and across the whole forest of worlds.

For someone standing in that forest, there would be no way out—in all directions, a mirror.

I’m going to tell you a story. And, like so many stories, this one begins with a body.

LAINA CALVARY

SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS

TWO WEEKS BEFORE THE FRACTURE

It is October 2022, and Lincoln is dead.

Laina stands over her brother’s body, looking at the thin white sheet that covers his lower half. The sheet looks more real than the man, though she can’t say why. Perhaps it’s because she is used to seeing life in her brother, and now there is only this dead outer covering. Lincoln’s skin looks like dried wood now, his nose and lips taking on the quality of wax. All signs of something lost that cannot be touched, noticed only in its absence.

Her brother is filled with holes. The ear canals and nostrils and pores are all useless now, but familiar. The punctures along his arms are also familiar, markers of a time when Laina was close enough to see the damage he was doing to himself. But now there are two new holes, large and unfamiliar. One is just below his heart, the other above his right brow. Either would have killed him easily, but there they are, a constellation of two to show that the job was properly done.

How long has she been in here alone, looking at these holes? Laina asked to be alone with the body, and the coroner obliged. She wants to go to the door and call the coroner back in, but she can’t pull herself away. She looks the body over again, from feet to head. She focuses on his overgrown beard once more. This was the other thing that had stopped her from identifying him quickly. The beard and the lifelessness. Before this, she’d seen him at their mom’s funeral seven years ago, standing under a naked tree, its fingers branching to the pale sky. He wore large sunglasses over his face and a torn winter jacket. He was far away, but it was him all right. Facial hair, sure, but not this ugly thing. And then she saw him again on the Red Line, on her way home to Somerville, maybe three years past? Something like that. On that occasion, she got a good look at him, exchanged words. His beard was long then too, but still manageable.

He was naked when he died, the coroner explained—running through the street as bare as on the day he was born. It must have been an episode, she thinks. High out of his mind, but not dangerous. Right? He clearly couldn’t have been armed. He had nowhere to hide a weapon. Laina feels a surge of anger at this thought. Don’t do it, she tells herself. Don’t go there, not now. She sets the thought on fire and lets the smoke curl away to nothing before it can do any harm. Anger she will have to save for later, when it can be used.

It is the whole moment, really. Her brother’s body on the slab, the subject of her thoughts. It feels so familiar, as if Cory were lying there too, dead and full of holes.

When they were children, Lincoln and Laina’s cousin would come over to cut Lincoln’s hair. Simone was nine years older than Laina, already out of high school and doing nothing with her life except for her hair-cutting side hustle. She cut Lincoln’s hair for free, but she charged all the neighborhood boys so she had spending money she didn’t have to beg from Auntie Jane.

Simone liked to do her haircuts in the bathroom, sitting Lincoln on top of a wooden stool so that she could see the boy in the mirror as she did her work. This meant that Laina had to make sure to use the bathroom before she came over. She was shy, and something about Simone made her uncomfortable, so she tried to avoid her and the bathroom if she could.

But sometimes, even with all her planning, she still had to open the closed door, interrupt the haircutting—which Simone was never happy about—and grab her scrunchies or comb or brush or Blue Magic before slipping back out again. On those occasions, she planned meticulously, remembering in her mind’s eye what she needed and where to find it. Then she took a breath, turned the knob, and opened the door, ready for a quick extraction.

The morning it happened, Laina had forgotten her vented hairbrush and was already late for school. She took her breath. She turned the knob. She flung the door open, revealing the crowded bathroom, her brother, and her cousin.

Simone pulled her hand away from Lincoln’s lap. “What do you want?” she yelled, flicking off the hair clippers in her other hand.

Laina tried to make eye contact with Lincoln, but his head was lowered. He had a look about him, as if he were trying not to take up space, shrinking into himself. She couldn’t decide whether it was him shaking, or her.

“This fucking girl . . .” Simone stepped toward Laina, mumbling something under her breath. Laina cringed in preparation, but Simone only reached out her hand and pulled the door shut, right in Laina’s face.

Laina stood there. Around her, the cramped apartment held its breath. Then the hair clippers buzzed to life again from behind the closed door. Laina reached again for the knob but held back. Her cheeks were on fire. She wanted to tell someone something, to say something, but couldn’t put the words together.

Her mother had already left for work. Laina needed to get down to the bus. Simone had agreed to get Lincoln to school herself. All these thoughts, she knew, were connected somehow, but they floated rootless above her. Laina didn’t remember a lot after that—only that her hair was messy that day and a boy at school had called her nappy-head. She cried and couldn’t stop. She couldn’t remember anything after that day, either. A haze swallowed the weeks and months of memories that followed. Simone continued coming over to cut Lincoln’s hair, she knew, until one day she stopped. And eventually, that sick feeling went away, though she couldn’t pinpoint when.

But here it is, back again, knocking on the old closed door in the back of her mind, returned to fill the silence left behind by those two bullets.

Laina keeps staring at the body, unable and unwilling to look away.

“You blame yourself,” I say.

It isn’t really a question, but Laina answers the way I always have: “How could I not?”

Our conversation ends there. The coroner comes back in and says, “Time to go.” The words fail to catch Laina’s attention the first time, and after a while standing next to her, the coroner says it again and guides her out.

The room lies quiet after they leave. Only machine hums and the mute dead.

The thing is, Laina had decided to use one of her sick days. The bookstore calls these “wellness days” to encourage their use more broadly. Laina wasn’t sick, but she wanted to stay home and binge-watch The Americans. It was pure happenstance she wasn’t at work when she got the call that the fingerprints of an unidentified person matched her brother’s. Since her husband, Ridley, was already at work in the bookstore, he wasn’t with her when she got the news. Laina made no conscious decision to keep it from him, but now, after seeing the body, calling him doesn’t seem right.

Still in shock, she parks her car on Summer Street near their apartment and starts down the steep hill to Union Square. The square was once a recruitment and mustering site for the Union Army in the Civil War, hence the name. It’s located at the intersection of Somerville Avenue, Prospect Hill, and Washington Street, just a fifteen-minute walk from Laina and Ridley’s apartment—a huge convenience. Their store, Anarres Books, lies right at the junction of the three streets. They started renting the space after a Korean grocery moved to Medford. Laina didn’t know Ridley when the bookstore opened. It took her a year to discover the store, and several months before they had an opening she could apply for. Ridley and three others co-owned the bookstore at the time, and within another couple of years, it had five worker-owners, Laina among them. She had never worked at a cooperative, but she knew she wanted to. She also loved books, which helped. Falling in love with Ridley happened later. It was slow and easy, like wearing in a good shoe. Ridley never liked that analogy, but that was what it felt like for Laina.

When she walks into the bookstore, she’s fine. She even greets a few coworkers without getting any strange looks or questions. But when she sees Ridley, they lock eyes, and she can’t even get to him before the tears start streaming out. He comes right to her and pulls her into a hug.

“What is it, babe?”

She tells him.

“Oh God,” he says. He holds her as they make their way back through the bookstore, having to field questions from Madeline at the information desk.

At home, they sit in the living room, his arm around her. She can’t speak, and he doesn’t push her to. She falls into her own thoughts, and when she comes out, a half hour has passed as if by magic.

“Tea,” Ridley offers. He just seemed to be waiting there, waiting for her to come out again, so he could make the offer. She nods, and he dutifully disappears to the kitchen.

In the living room, a bird of happiness hangs over the TV, its thin wooden wings in perpetual flight. It is spinning, propelled by a stream of air coming in the cracked window. The apartment is filled with similar objects, all Ridley’s creations: a wooden bowl on a thin shelf, with pens in it; a varnished spoon that differs only slightly from the ones they use in the kitchen; a crude dragon wrapped around a wood stump. There is another bird of happiness in their bedroom, and several bowls, spoons, and spatulas in the kitchen; a small box in their second bedroom/office, heaping with rocks they’ve collected, some ordinary, some with embedded crystalline structures. And Ridley’s most treasured possession: a wooden shelf, also in that second bedroom. An ugly thing, cracked and uneven, so that books fall over if they’re not wedged in tight. But it was Ridley’s first large project, so it remains. And Laina would never admit that she hates to look at it.

Ridley returns with a cup of steaming milk tea and sets it on the table. “Do you need me to call people?”

Laina thinks about that. Should she wait until she can make those calls herself, or let Ridley help with this too? The decision is easy.

“Call my aunt. She’ll tell everyone.”

There aren’t that many people to tell, really. Lincoln cut ties with most everyone, and Laina, for her part, maintains only a few familial relationships.

Ridley makes a motion to stand, but Laina stops him. “In a minute,” she says. “Sit with me.” Her husband settles back down with her and puts a hand on the small of her back.

The tears begin again.

Over the next couple of weeks, Laina buries herself in funeral arrangements. Time blurs, and she makes no effort to keep track. She makes phone calls, pools the money from willing family members, pays for the casket, the viewing, the burial. Her husband’s hands are on her back, stroking her arms, her shoulders. He is kissing her forehead. It is night and day and twilight as she stands at her bedroom window, staring out at clouds and sun and stars. Then she is walking down the center of some high-ceilinged church and there are whispers and someone hugs her and someone else tells her that he is so sorry for her loss. There is singing and the lowering of the casket. There’s a man in robes saying words from the good book. Someone is putting her in the back of a car, and she is arriving at a reception hall with food and drinks and somber-looking people trying not to look at her. More people say more words and the audience makes soft murmurs of agreement, and then they ask her if she will speak. To this she shakes her head, and not a word is required of her. She is standing by the ice bucket and water pitchers when Ridley lets go of her hand and tells her he’s going to the bathroom and will be back soon. And somehow, Simone is there as soon as her husband leaves.

“Fucking tragedy,” Simone says. Her cousin is older now, graying. “I talked to one of the witnesses. They didn’t even help the boy. Just let him bleed out on the street.”

Laina tilts her body to face Simone. The fog retreats.

“There’s a tape,” her cousin is saying. When Laina doesn’t respond, she adds, “I know some people. The cops are keeping it real tight.”

A smile almost touches Simone’s lips when she says she knows some people. But she keeps it down, fights it back, as a decent person would, even though she isn’t a decent person. The fog is completely gone now, Laina’s fire lighting again.

“He was a good kid. He was struggling, but everyone has their share, you know? We all struggle. He was a good kid, though. It was that cop.”

Laina’s husband is walking toward them. He slows and then stops, worry on his face.

Simone shakes her head. “Loved that boy.”

And it is as if Laina were watching it happen from somewhere else. She sees Ridley start toward her but also sees Simone fleeing. She watches herself grab the back of Simone’s neck. She feels her nails dig in. She hears herself: “Motherfucker.” It isn’t a yell. It is calm, cold, lower than her own voice. It makes the hairs on her neck stand up.

“What are you doing?” Simone is asking as she turns, her hands raised. Laina clenches her other hand into a fist and punches Simone hard in the ear. She feels the skin on her knuckle split as she makes contact with the cubic zirconia stud in Simone’s earlobe.

Ridley is there, holding her. “Stop,” he says. “Baby, please stop.”

Simone wrests Laina’s hand from her neck. “What is wrong with you!”

Her ear is bleeding, and so is Laina’s hand. Simone dances back away from Laina, but Laina lunges again, dragging Ridley with her. Simone is too far away, though, and others have come between them.

Simone makes her way across the room, looking back and swearing. Laina screams as if some animal trapped in her had finally been released. She claws at the air. Auntie Jane puts her arms around Laina. “Calm down, love,” she says. “I know. I know.”

“You don’t,” Laina says.

Auntie Jane looks at her with sad eyes. “Get her some fresh air,” she tells Ridley.

“Let’s go, baby,” he says.

Simone, like the scared rat she is, has bolted out the front entrance, so Laina calms and lets Ridley lead her out the side exit.

Outside the open door, Auntie Jane tells one of her daughters to get a wet cloth napkin. When her youngest returns, Auntie Jane takes the cloth and wraps it around Laina’s hand. A few people crowd by the door, staring out at her. Only then does Laina begin to feel the slightest bit of embarrassment.

The alleyway stinks of piss and garbage. She looks up at the sky, trying to control her breath through her mouth, and before long the nausea recedes. An expensive car buzzes by, and Laina realizes where she is.

Jamaica Plain has been sufficiently gentrified, but some of its prior harshness still remains: this alleyway, a reminder of its previous life and the desperation that underlies every large city. Nothing is completely washed away. Not ever. She left the old neighborhood, going off to college and trying to stay away, but here she is again. Things change, but they always wrap back around on themselves, circles within circles. Her brother is dead, but his death is just a change of state really. How many times did she bury him already? How many more times will she have to bury him?

* * *

Time blurs again, and she is staring out her bedroom window, the night dark and starless, silent as if the mouth of a giant had swallowed the world.

When Lincoln was seventeen, he disappeared for a couple of days, and Laina had to go looking for him. She found her brother over at his friend Tomas’s house in Roxbury. Their mom had called everywhere, but not there. Her mother did not know Tomas, and Lincoln never mentioned him. Laina had met him at Lincoln’s last birthday party. He was twenty, though he looked at least a decade older, standing in the corner. It was more of a hang-out than a party—some music, some dancing, but mostly just teenagers sitting around drinking and talking. Tomas looked as if he didn’t belong, so Laina chatted him up. By the end of that first conversation, she knew the sort of person Tomas was. After the party, she had asked around about him, found out where he lived, just in case.

Lincoln didn’t like people getting involved in his business. Laina learned how to get involved at a distance, which mostly worked out to learning things without Lincoln knowing she knew. And so, in this case, she knew where her brother might be, once the obvious places were ruled out.

Laina had to knock several times before Tomas answered the door. When he did, she forced her way in to find Lincoln on the couch, sprawled out, his eyes half rolled back. The smell of burnt chemicals clung to the air around him. He didn’t acknowledge her at all. He lay there as if stunned.

“Lincoln,” she called, but then could find no words.

Laina turned to glare at Tomas. “Do you have anything to do with this?”

“This?” he repeated, and looked at Lincoln as if just discovering he was there. His eyes were wet. He was swaying. “He wanted to. It has nothing to do with me.”

“You should hang out with people your own age,” Laina said.

“Like you?” Tomas smiled, showing stained teeth.

“Wipe that smile off your face before I—”

“Leave him alone,” Lincoln said. It was soft enough that, for a moment, Laina thought she imagined it. But when she looked at him, he was looking back at her, his eyes more focused than before, though he had trouble keeping his head from rolling back.

“You knew, didn’t you?” he said.

The question came so out of nowhere that Laina looked at Tomas to see if she’d missed something. Tomas shrugged.

“Knew what?” she asked.

Lincoln laughed. It was weak and ragged, but there was no mistaking it. It ran along, dipping and rising again, his body hopping along the track with it, until the laugh descended into a trembling terrible enough to make Laina’s heart sink with worry. And then it wasn’t laughter. Lincoln shut his eyes tight as if he’d been hit, and his body rolled forward in violent sobs. He put his hands to his face. His body was crouched over like a serpent eating its own tail. And then he toppled over to one side on the couch, still curled into himself, and continued crying quietly.

Laina felt that old feeling. She wanted to reach out and give him comfort, but the child in her was glued in place. The rock in her throat shifted. Her eyes burned.

How much time passed? Minutes? An hour? Tomas was on the floor now, in the same spot he had been standing, looking away with something like embarrassment. Eventually, the crying stopped. Lincoln uncoiled himself slowly. Then he reached for a Ziploc bag resting on the table, pulled out two pills, and crushed them with an ashtray. Just like that, his eyes on Laina the whole time.

“You doing that in front of me?” Laina asked, hoping he would stop even if just to consider the question.

Without a pause, Lincoln took a rolled-up dollar bill and sucked in hard. He wiped his nose. “You’re no one,” he said.

The statement had enough venom in it to reach across time and space and strike me in the chest.

Laina pursed her lips. “Kill yourself if you want. But I’m not going to be here when you do.” She shot Tomas one last evil eye and walked past him, making sure to nudge him aside with her leg. “I’ll tell Mom where to find you,” she said before stepping out the door.

She didn’t see him again for another three years.

Three days after the funeral, Laina comes back from work to find Ridley sitting in front of his laptop at the dining room table wearing his big over-the-ear headphones. When she enters, he looks up, tucks the right ear pad behind his ear, and mouths a noiseless good night, my love.

Laina can hear the voices coming from his headphones: another SEN Collective meeting. She smiles, mouths shower, and goes down the hall to the bathroom. She undresses and hops in the bath and takes a quick one, then spends several minutes standing in the tub, letting the water drip from her fingertips. The door is slightly ajar to let the steam out, so she hears when Ridley gets up from the table and stomps down the hall. The door creaks open. She rolls the shower curtain back just enough to see him poke his head in.

“You’re home early,” he says. “Bad day?”

“No, just not a good one.”

He slips into the bathroom and stands by the light switch, giving her the silent nod to go on.

She sighs but relents. “Our coworkers stayed pretty much out of my way. They asked how the funeral went but didn’t pry about Lincoln. I did my shift at information—a few out-of-store book requests and the usual stuff. I tried to be friendly, smile at the regulars, but I was off and no one bought it, and so they let me leave early, told me if I wanted I could try again tomorrow. So not too bad, not too good.”

He leans his head back against the wall. “And will you be coming in tomorrow? I’m supposed to be on the afternoon shift.”

Laina shrugs. “Maybe.” She motions for him to give her the towel, and he pulls it down from the hook and hands it to her. As she dries off, she changes the subject. “How was the meeting?”

“Same old. They want the fall retreat to be three days, but I’m trying to get it down to two.” He looks meaningfully at her.

Laina wraps the towel around her and steps out of the shower. “Take the three days,” she says. “I’ll be okay.”

“You’re sure?” When she nods, his shoulders ease just a bit, and he takes a breath. “So, is there any news on the investigation?”

Laina grunts and leans on the sink.

“I shouldn’t have asked.”

“It’s okay.” Laina shakes her head. “Nothing. No mention of a video, either.” She doesn’t want to admit it, but she feels tired. She wants it to be over. All that anger she wants to feel has been sucked out of her by the whole ordeal. “Can we just go to bed?” she asks. “I want to be held. I don’t want to talk.”

Ridley gives her a sad smile. “Okay, my love.”

She gets dressed in her shorts and sleeping shirt and gets into bed. Ridley is there waiting for her. She snuggles up against his shoulder and whispers, “You ever feel like there’s a world beneath this one?”

“What do you mean?” Ridley’s breath rises and falls, his heart beating steady as a drum.

Laina struggles for the words. “Like we are a speck on some larger thing that we only catch glimpses of.”

He hesitates, then asks, “Is this about the investigation?”

“I guess. But more than that.” She sighs. “I don’t know. Never mind.”

Ridley makes a sound as if he’s going to talk again, but doesn’t. Laina snuggles deeper into him, and he kisses her on the temple. He keeps his face to hers, so she feels his breath on her. This is reassuring. She is feeling shaky and needs his steadiness.

She tries to settle the matter in herself, but her mind frets on. She can’t tell what she knows from what she doesn’t, what she wants from what she only thinks she should want. Lincoln’s toxicology report returned inconclusive, but that still doesn’t explain why he was running through the street naked. Does she want people digging into his past, unearthing all the ugly, unsavory moments of his life to discredit him, diminish his humanity? She says she will fight for him, but if she decides not to fight, will it be to spare him that disgrace, or to spare herself? Will it be a gift, or just another betrayal? And if it is a bit of both, how much of each is permissible? Where is the line that would damn or redeem her? And shouldn’t she know? Shouldn’t she have the ability to unearth the truth of her own heart?

This is only part of what she wants to say to Ridley. The other part feels too strange, too terrible, too nihilistic to say out loud. She is feeling, deep inside herself, that none of it matters anyway. None of it matters, because none of it is real. An image comes to mind. She is a ship, and so is everyone else: a cluster of ships on a dark sea. They are all packed tightly together for protection, but it is futile because at any moment, some black hand will pull one or two or all of them under, and everyone will see it, but no one will know what they’re seeing or what to do about it. Not just dying, but something deeper than dying. The place that dying comes from—the vast and heavy nothing at the bottom of all things, returning to claim all things. Everything—her life, Lincoln’s life, the movements of every life—is the mere useless stirrings on the surface of that nothing. The nothing is real. They are not.

The thoughts persist. Ridley is asleep now, and the quiet drumbeat of his heart keeps time as Laina’s consciousness bobs along with no destination. Her restlessness dulls to the obsessive thoughts of someone on the verge of sleep, fighting against it with a relentless anxiety. But eventually, the thoughts turn to static, her anxiety softens, and without even realizing it, Laina inevitably slips beneath the tide.

* * *

Laina is on the subway platform for the Red Line to Alewife. The train is just arriving. She is standing just beyond the yellow line, where you’re not supposed to stand. The hot wind hits her face, pushed ahead of the train as it comes through the tunnel and into the more open space of the station. It screeches to a stop. The double doors open with a clamor. Laina steps through.

It is late; hardly anyone is in the subway car. She takes her seat across from a man asleep under a dirty child-size blanket. She doesn’t recognize him right away, but once she does, she spends the next few minutes staring at his sleeping face. A stop goes by, then another, before her brother opens his eyes. The action is slow, as if he were in his own bed, stirred awake by a lover. His eyes focus on hers but with no recognition. She may as well be a stranger.

Everything is hyperreal, vibrant: the textured face, the yellowed and bloodshot eyes. His skin gleams with days of grime. His forehead has a smudge of dirt; his cheeks are cratered with pockmarks. At the next stop, someone sits near Laina, but they are out of focus, the hyperreality of Lincoln sucking the reality from everything else.

“What, you going to take me home?” As always, he says this as if they’d been talking all along.

“If you’d let me,” she says. To her own ears, her voice sounds as if the volume had been turned all the way down.

“I got a place.”

Laina looks at the weather-worn duffel bag at his feet, the child’s blanket, caked with dirt, that he’s using for warmth. “Please come home with me.”

“Admit it,” he says.

This time, Laina doesn’t lie to herself. She knows what he is talking about—has always known. She thinks of saying, How could I know? Or, I’m sorry. Or, I didn’t see anything; you should have told me something was wrong. A dozen more answers present themselves, all of them terrible.

Finally, she chooses the truth. “I knew something, but it scared me.”

He laughs, that same laugh that has no joy in it. It turns to coughing. Then she notices that a darker patch on his covers is spreading. Was that there before? And with the logic of dreams, she remembers that he’s been shot. That he is dying.

The world around them suddenly dissolves, until it is just them, and then even Lincoln is fading. Almost simultaneously, another thing happens. Her brother is peeling. Slowly at first, quicker now, his whole body turning inside out from that dark wound. Inner flesh and fat expose themselves, the sound of it tearing at her eardrums, and then the space between them starts seeping into the black hole. She feels herself pulling apart too, strand by strand, the scream in her throat sucked out of her and into him. She is reaching her hands up to her neck and mouth, where she finds . . . nothing. A gaping hole where all her bits are spilling out into the open air.

Laina gasps awake. Her nightshirt is drenched in sweat. Around her, the room lies dark and silent. She puts a hand to her chest and takes enough slow breaths to settle her heart.

It is only after she relaxes that she has the feeling someone else is in the room. She doesn’t have a reason to think this; there is no evidence other than the feeling. But then a voice comes, hovering just above her head, a whisper: “Do you want me to get the video for you?”

It is a woman’s voice. Sweet. Not at all threatening. Laina is too stunned to speak.

I am just as shocked as she is. No one is there. No one has been there.

“I can get you the video,” the woman continues. “Show you what happened that night. Do you want to know what happened that night?”

The voice sounds Caribbean. Laina has family from St. Lucia, and the woman’s voice sounds something like that, but also different. I recognize the accent because I’ve heard it all my life. It isn’t St. Lucian; it’s St. Thomian. This woman, whoever or whatever she is, has a background similar to my own.

“I can find almost anything,” the voice says. “The world is filled with secrets I’ve found. This is just a small thing.”

“I want it,” Laina hears herself say. Her right hand is inching toward the lamp next to her bed.

“What will you do with it once you have it?” the voice asks. It is closer now, right in her ear.

Laina trembles. “I don’t know,” she says. “I’ll know once I have it.” The thought occurs to her that she has just given her soul to the devil. “What do you want in return?”

“Nothing at all,” the voice says. “Give me a day. I’ll—”

Laina flicks on the lamp. And somehow, this is worse: to see an empty room in the light. Finally, she screams.

“Maybe I should call off today.”

Laina tries on her best smile, kisses Ridley on the forehead, and lingers close to his face. “It was a bad dream,” she says. “Really. I’m fine.”

Ridley looks deep into her eyes but doesn’t say a word, which tells her that her act hasn’t worked, but she may still get away with it. “Okay,” he says. “Call me if there’s any trouble.”

When he leaves, Laina finds herself alone in the apartment. It wasn’t a bad dream. She’s sure she was awake, sure she had escaped that terrible dream into a reality just as terrible, because suddenly Ridley was there with her, his arms around her in the very same moment she flicked on the light and screamed.

Quietly she entertains another possibility. The black hand. Perhaps, it has a voice as well.

Perhaps, I think as well, entertaining the possibility that there are stranger things in the universe than I.

As I follow, Laina checks every room several times before she settles in the kitchen. She kicks herself up onto the countertop. She has no idea why this feels like the safest place to be, but she stays there until a knock at the door stirs her. She hops down and approaches the front door as if nearing a cliff edge. She thinks, no one shows up at their apartment without invitation. All the people Laina knows intimately enough to call friends are at work. Maybe a neighbor? But why?

She doesn’t want to think it could be a dangerous stranger or, maybe worse, the voice taken physical form.

She pushes through her fear and unbolts the door. When she opens it, a young woman is standing there.

“Good morning,” she says. “My name is Rebecca. I was a friend of Lincoln’s?”

Laina nods in answer to the unasked questions. Yes, she knows who Lincoln is. Yes, she is his sister. “Laina. Nice to meet you.”

Rebecca has strong eyes. She is very attractive and well put together. Laina hates herself for observing that, for thinking that this could not truly be Lincoln’s friend. And then she realizes she’s spent an uncomfortable amount of time just staring at the woman. “I’m sorry. Please come in.”

Laina leads Rebecca to the living room and then gets them each a glass of water. She places the glasses on the table between them, taking the love seat and giving Rebecca the couch to herself.

Rebecca gives her a disarming smile. “I called some family members and got your address. I hope that was okay.”

It isn’t, but Laina smiles back. “No problem.”

“I don’t know how else to say it, so I’ll just say it.”

Having said this, the woman, Rebecca, hesitates anyway. Laina is both amused and wearied. She waits as patiently as she can, watching several expressions pass over Rebecca’s face, none of them immediately telling since she doesn’t know the woman.

Finally, Rebecca says, “Lincoln was coming to see you before he died.” She reaches for her glass and takes a long gulp of water.

“That day?” Laina asks.

“No. Well, I don’t know. Sometimes, a . . .” Rebecca stops herself. She seems to reconsider her wording and tries again. “No, but he was planning to come see you. He was killed before he could.”

Was killed. A deliberate choice of words. Laina can detect some anger in them, too. Rebecca must have been really close to Lincoln to know so much, to feel so passionately about how he died. Laina decides just to be blunt about it. “Were you a lover?”

Rebecca laughs. Again, it is disarming, smooth like melted butter. “Oh, no. No, I’m not Lincoln’s type. And he definitely isn’t mine. Wasn’t mine.”

Laina frowns but presses on. “Best friend, then?”

“Maybe,” Rebecca says. “He wasn’t always in the mood for that.”

Laina understands this. Her brother could be prickly, occasionally unkind. “So why was he looking for me?” she asks. Laina looks down at her lap. She is wearing blue sweatpants covered in fuzz balls. She pulls a few off, realizes what she is doing, and stops. “I suppose it wasn’t good.”

“I think it would have depended on the outcome.”

“The outcome?”