1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

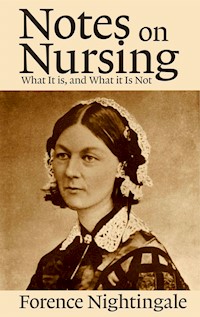

In "Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not," Florence Nightingale presents a pioneering discourse on healthcare that melds observational study with practical advice. Written in clear, direct prose, Nightingale demystifies the art and science of nursing, emphasizing the importance of environmental factors on patient recovery. This seminal text, informed by her experiences during the Crimean War, encourages a systematic approach to nursing, advocating for sanitation, proper nutrition, and patient observation, all framed within the Victorian ethos of moral responsibility and social reform. Florence Nightingale, often heralded as the founder of modern nursing, transformed the field through both advocacy and education. Her extensive work in hospitals and her rigorous statistical analyses bestowed her with insights that were revolutionary for her time. Nightingale'Äôs commitment to improving healthcare conditions stemmed not only from her personal convictions but also from a desire to elevate nursing to a respected profession, thus paving the way for nurses as indispensable healthcare professionals. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the foundations of nursing and healthcare reforms. Nightingale's work transcends its historical context, offering timeless insights relevant to contemporary discussions on patient care and healthcare practices. Engaging with this text illuminates the essential principles that continue to shape the nursing profession today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not

Table of Contents

PREFACE.

The following notes are by no means intended as a rule of thought by which nurses can teach themselves to nurse, still less as a manual to teach nurses to nurse. They are meant simply to give hints for thought to women who have personal charge of the health of others. Every woman, or at least almost every woman, in England has, at one time or another of her life, charge of the personal health of somebody, whether child or invalid,—in other words, every woman is a nurse. Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognized as the knowledge which every one ought to have—distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have.

If, then, every woman must at some time or other of her life, become a nurse, i.e., have charge of somebody's health, how immense and how valuable would be the produce of her united experience if every woman would think how to nurse.

I do not pretend to teach her how, I ask her to teach herself, and for this purpose I venture to give her some hints.

VENTILATION AND WARMING HEALTH OF HOUSES PETTY MANAGEMENT NOISE VARIETY TAKING FOOD WHAT FOOD? BED AND BEDDING LIGHT CLEANLINESS OF ROOMS AND WALLS PERSONAL CLEANLINESS CHATTERING HOPES AND ADVICES OBSERVATION OF THE SICK CONCLUSION APPENDIX

WHAT IT IS, AND WHAT IT IS NOT.

* * * * *

[Sidenote: Disease a reparative process.]

Shall we begin by taking it as a general principle—that all disease, at some period or other of its course, is more or less a reparative process, not necessarily accompanied with suffering: an effort of nature to remedy a process of poisoning or of decay, which has taken place weeks, months, sometimes years beforehand, unnoticed, the termination of the disease being then, while the antecedent process was going on, determined?

If we accept this as a general principle, we shall be immediately met with anecdotes and instances to prove the contrary. Just so if we were to take, as a principle—all the climates of the earth are meant to be made habitable for man, by the efforts of man—the objection would be immediately raised,—Will the top of Mount Blanc ever be made habitable? Our answer would be, it will be many thousands of years before we have reached the bottom of Mount Blanc in making the earth healthy. Wait till we have reached the bottom before we discuss the top.

[Sidenote: Of the sufferings of disease, disease not always the cause.]

In watching diseases, both in private houses and in public hospitals, the thing which strikes the experienced observer most forcibly is this, that the symptoms or the sufferings generally considered to be inevitable and incident to the disease are very often not symptoms of the disease at all, but of something quite different—of the want of fresh air, or of light, or of warmth, or of quiet, or of cleanliness, or of punctuality and care in the administration of diet, of each or of all of these. And this quite as much in private as in hospital nursing.

The reparative process which Nature has instituted and which we call disease, has been hindered by some want of knowledge or attention, in one or in all of these things, and pain, suffering, or interruption of the whole process sets in.

If a patient is cold, if a patient is feverish, if a patient is faint, if he is sick after taking food, if he has a bed-sore, it is generally the fault not of the disease, but of the nursing.

[Sidenote: What nursing ought to do.]

I use the word nursing for want of a better. It has been limited to signify little more than the administration of medicines and the application of poultices. It ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet—all at the least expense of vital power to the patient.

[Sidenote: Nursing the sick little understood.]

It has been said and written scores of times, that every woman makes a good nurse. I believe, on the contrary, that the very elements of nursing are all but unknown.

By this I do not mean that the nurse is always to blame. Bad sanitary, bad architectural, and bad administrative arrangements often make it impossible to nurse.

But the art of nursing ought to include such arrangements as alone make what I understand by nursing, possible.

The art of nursing, as now practised, seems to be expressly constituted to unmake what God had made disease to be, viz., a reparative process.

[Sidenote: Nursing ought to assist the reparative process.]

To recur to the first objection. If we are asked, Is such or such a disease a reparative process? Can such an illness be unaccompanied with suffering? Will any care prevent such a patient from suffering this or that?—I humbly say, I do not know. But when you have done away with all that pain and suffering, which in patients are the symptoms not of their disease, but of the absence of one or all of the above-mentioned essentials to the success of Nature's reparative processes, we shall then know what are the symptoms of and the sufferings inseparable from the disease.

Another and the commonest exclamation which will be instantly made is— Would you do nothing, then, in cholera, fever, &c.?—so deep-rooted and universal is the conviction that to give medicine is to be doing something, or rather everything; to give air, warmth, cleanliness, &c., is to do nothing. The reply is, that in these and many other similar diseases the exact value of particular remedies and modes of treatment is by no means ascertained, while there is universal experience as to the extreme importance of careful nursing in determining the issue of the disease.

[Sidenote: Nursing the well.]

II. The very elements of what constitutes good nursing are as little understood for the well as for the sick. The same laws of health or of nursing, for they are in reality the same, obtain among the well as among the sick. The breaking of them produces only a less violent consequence among the former than among the latter,—and this sometimes, not always.

It is constantly objected,—"But how can I obtain this medical knowledge? I am not a doctor. I must leave this to doctors."

[Sidenote: Little understood.]

Oh, mothers of families! You who say this, do you know that one in every seven infants in this civilized land of England perishes before it is one year old? That, in London, two in every five die before they are five years old? And, in the other great cities of England, nearly one out of two?[1] "The life duration of tender babies" (as some Saturn, turned analytical chemist, says) "is the most delicate test" of sanitary conditions. Is all this premature suffering and death necessary? Or did Nature intend mothers to be always accompanied by doctors? Or is it better to learn the piano-forte than to learn the laws which subserve the preservation of offspring?

Macaulay somewhere says, that it is extraordinary that, whereas the laws of the motions of the heavenly bodies, far removed as they are from us, are perfectly well understood, the laws of the human mind, which are under our observation all day and every day, are no better understood than they were two thousand years ago.

But how much more extraordinary is it that, whereas what we might call the coxcombries of education—e.g., the elements of astronomy—are now taught to every school-girl, neither mothers of families of any class, nor school-mistresses of any class, nor nurses of children, nor nurses of hospitals, are taught anything about those laws which God has assigned to the relations of our bodies with the world in which He has put them. In other words, the laws which make these bodies, into which He has put our minds, healthy or unhealthy organs of those minds, are all but unlearnt. Not but that these laws—the laws of life—are in a certain measure understood, but not even mothers think it worth their while to study them—to study how to give their children healthy existences. They call it medical or physiological knowledge, fit only for doctors.

Another objection.

We are constantly told,—"But the circumstances which govern our children's healths are beyond our control. What can we do with winds? There is the east wind. Most people can tell before they get up in the morning whether the wind is in the east."

To this one can answer with more certainty than to the former objections. Who is it who knows when the wind is in the east? Not the Highland drover, certainly, exposed to the east wind, but the young lady who is worn out with the want of exposure to fresh air, to sunlight, &c. Put the latter under as good sanitary circumstances as the former, and she too will not know when the wind is in the east.

Footnote

[1] [Sidenote: Curious deductions from an excessive death rate.]

Upon this fact the most wonderful deductions have been strung. For a long time an announcement something like the following has been going the round of the papers:—"More than 25,000 children die every year in London under 10 years of age; therefore we want a Children's Hospital." This spring there was a prospectus issued, and divers other means taken to this effect:—"There is a great want of sanitary knowledge in women; therefore we want a Women's Hospital." Now, both the above facts are too sadly true. But what is the deduction? The causes of the enormous child mortality are perfectly well known; they are chiefly want of cleanliness, want of ventilation, want of whitewashing; in one word, defective household hygiene. The remedies are just as well known; and among them is certainly not the establishment of a Child's Hospital. This may be a want; just as there may be a want of hospital room for adults. But the Registrar-General would certainly never think of giving us as a cause for the high rate of child mortality in (say) Liverpool that there was not sufficient hospital room for children; nor would he urge upon us, as a remedy, to found an hospital for them.

Again, women, and the best women, are wofully deficient in sanitary knowledge; although it is to women that we must look, first and last, for its application, as far as household hygiene is concerned. But who would ever think of citing the institution of a Women's Hospital as the way to cure this want? We have it, indeed, upon very high authority that there is some fear lest hospitals, as they have been hitherto, may not have generally increased, rather than diminished, the rate of mortality—especially of child mortality.

I. VENTILATION AND WARMING.

[Sidenote: First rule of nursing, to keep the air within as pure as the air without.]

The very first canon of nursing, the first and the last thing upon which a nurse's attention must be fixed, the first essential to a patient, without which all the rest you can do for him is as nothing, with which I had almost said you may leave all the rest alone, is this: TO KEEP THE AIR HE BREATHES AS PURE AS THE EXTERNAL AIR, WITHOUT CHILLING HIM. Yet what is so little attended, to? Even where it is thought of at all, the most extraordinary misconceptions reign about it. Even in admitting air into the patient's room or ward, few people ever think, where that air comes from. It may come from a corridor into which other wards are ventilated, from a hall, always unaired, always full of the fumes of gas, dinner, of various kinds of mustiness; from an underground kitchen, sink, washhouse, water-closet, or even, as I myself have had sorrowful experience, from open sewers loaded with filth; and with this the patient's room or ward is aired, as it is called—poisoned, it should rather be said. Always, air from the air without, and that, too, through those windows, through which the air comes freshest. From a closed court, especially if the wind do not blow that way, air may come as stagnant as any from a hall or corridor.

Again, a thing I have often seen both in private houses and institutions. A room remains uninhabited; the fireplace is carefully fastened up with a board; the windows are never opened; probably the shutters are kept always shut; perhaps some kind of stores are kept in the room; no breath of fresh air can by possibility enter into that room, nor any ray of sun. The air is as stagnant, musty, and corrupt as it can by possibility be made. It is quite ripe to breed small-pox, scarlet-fever, diphtheria, or anything else you please.[1]

Yet the nursery, ward, or sick room adjoining will positively be aired (?) by having the door opened into that room. Or children will be put into that room, without previous preparation, to sleep.

A short time ago a man walked into a back-kitchen in Queen square, and cut the throat of a poor consumptive creature, sitting by the fire. The murderer did not deny the act, but simply said, "It's all right." Of course he was mad.

But in our case, the extraordinary thing is that the victim says, "It's all right," and that we are not mad. Yet, although we "nose" the murderers, in the musty unaired unsunned room, the scarlet fever which is behind the door, or the fever and hospital gangrene which are stalking among the crowded beds of a hospital ward, we say, "It's all right."

[Sidenote: Without chill.]

With a proper supply of windows, and a proper supply of fuel in open fire places, fresh air is comparatively easy to secure when your patient or patients are in bed. Never be afraid of open windows then. People don't catch cold in bed. This is a popular fallacy. With proper bed-clothes and hot bottles, if necessary, you can always keep a patient warm in bed, and well ventilate him at the same time.

But a careless nurse, be her rank and education what it may, will stop up every cranny and keep a hot-house heat when her patient is in bed,— and, if he is able to get up, leave him comparatively unprotected. The time when people take cold (and there are many ways of taking cold, besides a cold in the nose,) is when they first get up after the two-fold exhaustion of dressing and of having had the skin relaxed by many hours, perhaps days, in bed, and thereby rendered more incapable of re-action. Then the same temperature which refreshes the patient in bed may destroy the patient just risen. And common sense will point out, that, while purity of air is essential, a temperature must be secured which shall not chill the patient. Otherwise the best that can be expected will be a feverish re-action.

To have the air within as pure as the air without, it is not necessary, as often appears to be thought, to make it as cold.

In the afternoon again, without care, the patient whose vital powers have then risen often finds the room as close and oppressive as he found it cold in the morning. Yet the nurse will be terrified, if a window is opened.[2]

[Sidenote: Open windows.]

I know an intelligent humane house surgeon who makes a practice of keeping the ward windows open. The physicians and surgeons invariably close them while going their rounds; and the house surgeon very properly as invariably opens them whenever the doctors have turned their backs.

In a little book on nursing, published a short time ago, we are told, that, "with proper care it is very seldom that the windows cannot be opened for a few minutes twice in the day to admit fresh air from without." I should think not; nor twice in the hour either. It only shows how little the subject has been considered.

[Sidenote: What kind of warmth desirable.]

Of all methods of keeping patients warm the very worst certainly is to depend for heat on the breath and bodies of the sick. I have known a medical officer keep his ward windows hermetically closed. Thus exposing the sick to all the dangers of an infected atmosphere, because he was afraid that, by admitting fresh air, the temperature of the ward would be too much lowered. This is a destructive fallacy.

To attempt to keep a ward warm at the expense of making the sick repeatedly breathe their own hot, humid, putrescing atmosphere is a certain way to delay recovery or to destroy life.

[Sidenote: Bedrooms almost universally foul.]

Do you ever go into the bed-rooms of any persons of any class, whether they contain one, two, or twenty people, whether they hold sick or well, at night, or before the windows are opened in the morning, and ever find the air anything but unwholesomely close and foul? And why should it be so? And of how much importance it is that it should not be so? During sleep, the human body, even when in health, is far more injured by the influence of foul air than when awake. Why can't you keep the air all night, then, as pure as the air without in the rooms you sleep in? But for this, you must have sufficient outlet for the impure air you make yourselves to go out; sufficient inlet for the pure air from without to come in. You must have open chimneys, open windows, or ventilators; no close curtains round your beds; no shutters or curtains to your windows, none of the contrivances by which you undermine your own health or destroy the chances of recovery of your sick.[3]

[Sidenote: When warmth must be most carefully looked to.]

A careful nurse will keep a constant watch over her sick, especially weak, protracted, and collapsed cases, to guard against the effects of the loss of vital heat by the patient himself. In certain diseased states much less heat is produced than in health; and there is a constant tendency to the decline and ultimate extinction of the vital powers by the call made upon them to sustain the heat of the body. Cases where this occurs should be watched with the greatest care from hour to hour, I had almost said from minute to minute. The feet and legs should be examined by the hand from time to time, and whenever a tendency to chilling is discovered, hot bottles, hot bricks, or warm flannels, with some warm drink, should be made use of until the temperature is restored. The fire should be, if necessary, replenished. Patients are frequently lost in the latter stages of disease from want of attention to such simple precautions. The nurse may be trusting to the patient's diet, or to his medicine, or to the occasional dose of stimulant which she is directed to give him, while the patient is all the while sinking from want of a little external warmth. Such cases happen at all times, even during the height of summer. This fatal chill is most apt to occur towards early morning at the period of the lowest temperature of the twenty-four hours, and at the time when the effect of the preceding day's diets is exhausted.

Generally speaking, you may expect that weak patients will suffer cold much more in the morning than in the evening. The vital powers are much lower. If they are feverish at night, with burning hands and feet, they are almost sure to be chilly and shivering in the morning. But nurses are very fond of heating the foot-warmer at night, and of neglecting it in the morning, when they are busy. I should reverse the matter.

All these things require common sense and care. Yet perhaps in no one single thing is so little common sense shown, in all ranks, as in nursing.[4]

[Sidenote: Cold air not ventilation, nor fresh air a method of chill.]

The extraordinary confusion between cold and ventilation, even in the minds of well educated people, illustrates this. To make a room cold is by no means necessarily to ventilate it. Nor is it at all necessary, in order to ventilate a room, to chill it. Yet, if a nurse finds a room close, she will let out the fire, thereby making it closer, or she will open the door into a cold room, without a fire, or an open window in it, by way of improving the ventilation. The safest atmosphere of all for a patient is a good fire and an open window, excepting in extremes of temperature. (Yet no nurse can ever be made to understand this.) To ventilate a small room without draughts of course requires more care than to ventilate a large one.

[Sidenote: Night air.]