Subsidiary Notes as to the Introduction of Female Nursing into Military Hospitals in Peace and War E-Book

Florence Nightingale

0,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

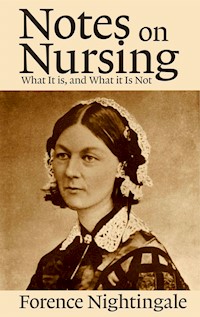

In "Subsidiary Notes as to the Introduction of Female Nursing into Military Hospitals in Peace and War," Florence Nightingale presents a detailed exploration of the role of female nurses within military healthcare systems, both during peacetime and wartime. Written in a clear, persuasive style, the text serves as both a practical guide and a passionate advocacy for the inclusion of women in military nursing. Nightingale meticulously documents her observations and experiences, reflecting a critical moment in the evolution of nursing as a profession and the broader societal shifts regarding gender roles in the 19th century, thereby positioning her work within the reform movements of her time. Florence Nightingale, a pioneering figure in nursing reform, was profoundly influenced by her own experiences during the Crimean War, where she witnessed the dire conditions of military hospitals. Her commitment to sanitation, patient care, and nursing education not only transformed military healthcare but also laid the groundwork for modern nursing practices. Nightingale's impressive background as a statistician and keeper of meticulous records informs the rigor and depth of her analysis presented in this book, showcasing her as one of the first to quantify health outcomes in a military context. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of healthcare, the evolution of nursing, or gender studies. Nightingale's pioneering spirit and bold advocacy for women in medicine resonate profoundly today, making her insights invaluable for contemporary discussions on gender equality and professionalization within healthcare fields.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Subsidiary Notes as to the Introduction of Female Nursing into Military Hospitals in Peace and War

Table of Contents

ILLUSTRATION.

DIGEST.

PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL.

Thoughts submitted by order concerning

I.

Hospital-Nurses.

II.

Nurses in Civil Hospitals.

III.

Nurses in Her Majesty’s Hospitals.

I. Hospital-Nurses.

1. It would appear desirable to consider that definite objects are to be attained; and that the road leading to them is to a large extent to be found out—therefore to consider all plans and rules, for some time to come, as in a great measure tentative and experimental.

2. The main object I conceive to be, to improve hospitals, by improving hospital-nursing; and to do this by improving, or contributing towards the improvement, of the class of hospital-nurses, whether nurses or head-nurses.

3. This I propose doing, not by founding a Religious Order; but by training, systematizing, and morally improving as far as may be permitted, that section of the large class of women supporting themselves by labour, who take to hospital-nursing for a livelihood,—by inducing, in the long run, some such women to contemplate usefulness, and the service of God in the relief of man, as well as maintenance, and by incorporating with both these classes a certain proportion of gentlewomen who may think fit to adopt this occupation without pay, but under the same rules, and on the same strict footing of duty performed under definite superiors. These two latter elements, if efficient (if not, they would be mischievous rather than useless), I consider would elevate and leaven the mass.

4. It may or may not be desirable to incorporate into the work, either temporarily or permanently, members of Religious Orders, whether English or Roman Catholic, or both, who may, with the consent of their Superiors, enter hospitals nursed under the above system, upon the definite understanding of entire obedience to secular authorities in secular matters, and of abstinence from proselytism.

5. Great and undoubted advantages as to character, decorum, order, absence of scandal, protection against calumny, together with, generally speaking, security for some amount of religious fear, love, and self-sacrifice, are found in the system of female Religious Orders.

6. On the other hand, the majority of women in all European countries are, by God’s providence, compelled to work for their bread, and are without vocation for Orders.

In England the channels of female labour are few, narrow, and over-crowded. In London and in all large towns, there are accordingly a large number of women who avowedly live by their shame; a larger number who occupy a hideous border-land, working by day and sinning by night; and a large number, whether larger or smaller than the latter class is a doubtful problem, who preserve their chastity, and struggle through their lives as they can, on precarious work and insufficient wages. Vicious propensities are in many cases the cause, remediless by the efforts of others, of the two first classes: want of work, insufficient wages, the absence of protection and restraint, are the cause in many more.

Perhaps the work most needed now is rather to aim at alleviating the misery, and lessening the opportunities and the temptations to gross sin, of the many; than at promoting the spiritual elevation of the few, always supposing that this latter object is best effected in an Order.

At any rate, to promote the honest employment, the decent maintenance and provision, to protect and to restrain, to elevate in purifying, so far as may be permitted, a number, more or less, of poor and virtuous women, is a definite and large object of useful aim, whether success be granted to it or not.

The Orders remain for the reception of those women who either are or believe themselves drawn to enter them, or who experience their need of them.

7. The care of the sick is the main object of hospitals. The care of their souls is the great province of the clergy of hospitals. The care of their bodies is the duty of the nurses. Possibly this duty might be better fulfilled by religious nurses than by Sisters of any Order; because the careful, skilful, and frequent performance of certain coarse, servile, personal offices is of momentous consequence in many forms of severe illness and severe injury, and prudery, a thing which appears incidental, though not necessarily so, to Female Orders, is adverse to or incompatible with this.

8. Grave and peculiar difficulties attend the incorporation of members of Orders, especially of Roman Catholic Orders, into the work. And, both with reference to the Queen’s hospitals, and still more to the civil hospitals, I humbly submit that much thought, and some consultation with a few impartial and judicious men, should precede the experiment of their introduction. This appears to me one of the most important questions for decision. Should it be decided in favor of their introduction, I trust it may be resolved to do so only tentatively and experimentally.

I confess that, subject to correction or modification from further experience or information, my belief, the result of much anxious thought and actual experience, is, that their introduction is certain to effect far more harm in some ways than it can effect good in others; that a great part of the advantages of the system of Orders is lost when their members are partially incorporated in a secular, and therefore, as they consider, an inferior system; and that their incorporation, especially as regards the Roman Catholic Sisters, will be a constant source of confusion, of weakness, of disunion, and of mischief.

Saint Vincent de Paule well knew mankind, when he imposed, amongst other things, the rule on the Sisters of his Order never to join in any work of charity with the Sisters of any other Order. This rule was mentioned to me on an occasion which gave it weight, by the Superior of the Sisters of Charity of one of the two Sardinian Hospitals on the Heights of Balaklava, in the spring of 1856, and by the Mère Générale at Paris, October 1854, when she was solicited by me, with the assent and sanction, both of the English and of the French Governments, to grant some of her Sisters to us at Scutari.

9. As regards ladies, not members of Orders, peculiar difficulties attend their admission: yet their eventual admixture to a certain extent in the work is an important feature of it. Obedience, discipline, self-control, work understood as work, hospital service as implying masters, civil and medical, and a mistress, what service means, and abnegation of self, are things not always easy to be learnt, understood, and faithfully acted upon, by ladies. Yet they cannot fail in efficiency of service or propriety of conduct—propriety is a large word—without damaging the work, and degrading their element. Their dismissal (like that of Sisters) must always be more troublesome, if not more difficult than that of the other nurses.

It might be better not to invite this element; to let it come if it will learn, understand, and do what has to be learnt, understood, and done: if not, it is better away.

It appears to me, but I may be quite mistaken, that, in the beginning, many such persons will offer themselves, but few persevere; that in time a sufficient number will form an important element of the work; more is not desirable.

It seems to me important that ladies, as such, should have no separate status; but should be merged among the head-nurses, by whatever name these are called. Thus efficiency would be promoted, sundry things would be checked, and the leaven would circulate.

There are many women, daughters and widows of the middle classes, who would become valuable acquisitions to the work, but whose circumstances would compel them to find their maintenance in it. These persons would be far more useful, less troublesome, would blend better and more truly with women of the higher orders, who were in the work, and would influence better and more easily the other nurses, as head-nurses, than as ladies. Whether or not the better judgment of others agrees with mine, my meaning will be understood.

In truth the only lady in a hospital should be the chief of the women, whether called Matron or Superintendent. The efficiency of her office requires that she should rank as a lady and an officer of the hospital. At the same time, I think it important that every Matron and Superintendent, (unless during war-service, when the rough-and-ready life and work required will probably be best undergone by women of a higher class) should be a person of the middle classes, and if she requires and receives a salary, so much the better. She will thus disarm one source of opposition and jealousy, and enough will remain, inseparable from her office.

The quasi-spiritual dignity of Sisters of Mercy is a thing sui generis. But the real and faithful discharge of the duties of the wards of a General Hospital, whether with reference to superiors, companions, or patients, is incompatible with the status, as such, of ladies. The real dignity of a gentlewoman is a very high and unassailable thing, which silently encompasses her from her birth to her grave. Therefore, I can conceive no woman who knows, either from information or from experience, what hospital duties are, not feeling as strongly as I do, that either the assertion or the reception of the status as such of a lady, is against every rule and feeling of common sense, of the propriety of things, and of her own dignity.

10. The question of the mode of Religion is an all-important one, and the choice of a mode bears far more directly upon this work than may, at first sight, appear. To give up the common ground of membership of the National Church is to give up a great source of strength.

St. John’s House, if it steers clear of the rock of prudery, undoubtedly possesses great advantages over a system of hospital nursing by promiscuous instruments. Not because it includes a Sisterhood, a system, in which I, for one, humbly but entirely disbelieve; but because the laborious, servile, anxious, trying drudgery of real hospital work (and to be anything but a nuisance it must ever remain a very humble and very laborious drudgery), requires, like every duty, if it is to be done aright, the fear and love of God. And in practice, apart from theory, no real union can ever be formed between sects. The work now proposed, however, must essentially forbear to avail itself of the bond of union of the National Church.

11. None but women of unblemished character should be suffered to enter the work, and any departure from chastity should be visited with instant final dismission. All applications on behalf of late inmates of penitentiaries, reformatories, of all kinds and descriptions, should be refused. The first offence of dishonesty, and, at the very furthest, the third offence of drunkenness, should ensure irreversible dismissal. No nurse dismissed, from whatever cause, should be suffered to return.

12. It is very important, if possible, to make provision for the disabled age of deserving nurses. It does not seem to me, I speak very diffidently, desirable to concentrate them in one or more large buildings. I believe half the inmates of half the alms-houses, &c., are not on speaking terms with each other. John Bull is of a peculiar idiosyncrasy: nowhere are there such homes as in England, but life in community does not seem congenial here. A pension and the option of ending their days in solitary quiet, or with some friend or relation, would probably be the most comfortable arrangement for nurses.

13. Many women are valuable as nurses, who are yet unfit for promotion to head-nurses. It appears to me that it would be very desirable to have an intermediate recompense: say, after ten years’ good service, to raise nurses’ wages; after a second ten years, to raise them further.

14. There should be an age for the reception and for the retirement both of nurses and head-nurses. I think no head-nurse should be under thirty.

15. Simplicity of rules, placing the nurses, in some respects, absolutely under the Medical man, and, in others, absolutely under the Female Superintendent, is very important; also, at the outset, to have a clear and recorded definition of these respective limits.

16. Economy is very important, with regard to the eventual extension of the work.

17. In the event of the nurses not being trained in Her Majesty’s service, advantage, it seems to me, would attend their beginning in a great established hospital; unless indeed it should be judged best to select and train a staff of nurses first in a smaller and quieter one. Yet much that would be unpleasant in the larger place would probably be beneficial. The restraint, control, contact with the masters, work, and order of things of a great and settled place, would materially help with reference to the nurses.

18. Common sense will assuredly make the fixed resolve; both to fulfil one’s duty, and to keep within it. It is as essential to do the latter as the former, and often more difficult, especially for women; most especially for hospital-nurses.

19. It appears to me most important to be free, once and for ever, from the injurious, untrue, and derogatory appendage of public patronage: what is called support in these days always ends in patronage. This work, truly understood, never has been, never will be, never can be, a popular work; for many reasons, one of which is that the public, of all orders, never can know anything of the real nature of hospital-work. With the best intentions, it will therefore make perpetual and impeding mistakes in “supporting” or patronizing it. Its support and patronage are equally injurious in different ways as regards our masters the medical men, ourselves the nurses, and people who are neither medical men nor nurses.

20. I end as I began. Let nothing be done rashly. Let us not be fettered with many rules at first. Let us take time to see how things work; what is found to answer best; how the work proceeds; how far it pleases God to accept and bless it. Let us be prepared, as I know well we must be, for disappointments of every sort and kind. What can any of us do in anything, what are any of us meant to do in anything, but our duty, leaving the event to God? His Will be done in earth, as it is in Heaven.

II. Nurses in Civil Hospitals.

1. The isolation of each head-nurse and her nurses appears to me very important. The head-nurse should be within reach and view of her ward both day and night. Associating the nurses in large dormitories tends to corrupt the good, and make the bad worse. Small airy rooms contiguous to the ward are best. The ward should have but one entrance, and the head-nurse’s room should be close to it, so that neither nurse nor patient can leave, nor any one enter the ward, without her knowledge.

2. All the nurses should rank and be paid alike, with progressive increase of wages after each ten years’ good service, or a slow annual rise, which is better.

3. The night-nurses should be on duty 12 hours, with instant dismissal if found asleep; 8 hours should be allowed for sleep, and 4 hours for daily exercise, private occupation, or recreation. If they have no time to themselves for their mending, making, &c., they do it at night, sometimes innocently, sometimes to the injury of the patients. I would not however prohibit occupation at night; as sometimes the ward-duty is slight; and doing something is far better and more awakening than doing nothing. This is one of the matters the head-nurse should constantly look to. I do not fancy, but at present am not positive about, cleaning or scrubbing at night. The night-nurse should have a reversible lamp, or something that without disturbing the patient, gives her light, brighter than the dim fire or gas-light properly maintained in the wards at night. She should have a room to herself.

4. The day-nurses should have eight hours’ sleep, and if it be possible, 4 hours daily for exercise, private occupation or recreation. They may have one room.

5. All provisions, &c., &c., should be as much as possible brought into the wards, or to the ward-doors, by lifts. Nothing should be fetched by the nurses. This would save much time; would enable the nurses to do more work, and yet have more leisure; and above all, would obviate the great demoralization consequent on the nurses, patients, and men-servants congregating in numbers several times daily.

6. The patients should be made as useful as possible, consistently with their capacities, inside the ward; but should be permitted to fetch nothing to it.

7. I strongly incline to have the scrubbing done in each ward, by a nurse assigned for that purpose, and for general attendance when the scrubbing is done. There should be hours for the scrubbing, before and after which it should not be done. This whole matter is one on which I am not positive at present.

8. At present, I incline to something of the following scale. Two wards, single are best, but it might be one double ward, with 40 beds, served by 1 head-nurse and 3 nurses. The head-nurse to superintend all things, and to do the dressings not done by the surgeons and dressers, assisted mainly by one nurse, whom she thus instructs in nursing. Another nurse to do the scrubbing, and mainly the cleaning, and when these are over to mind the ward during the remaining hours in turn or in conjunction with the first nurse. The third to be night-nurse. In the morning, before dressing begins, and before the night-nurse goes off duty, all three nurses to clean the ward, make the beds, wash the helpless patients, &c.

9. Hours of morning and evening poulticing and dressing to be fixed.

10. Hours of administration of medicine, always except at night given by head-nurse, to be fixed.

11. Hours of exercise of head-nurse and nurses to be fixed, and arranged with reference to the ward-duties. A fixed occasional holiday given in turn to the nurses is good. An annual longer holiday for them and for the head-nurses is good; a fortnight is, I think, a good limit. The holidays cause inconvenience, no doubt, but on the whole do, I think, far more good than harm. The holidays should be distributed in rotation during a fixed time of year, and comprehended in two or three months, or four at the very outside; and no woman declining her holiday at the proper time should be allowed it at any other.

12. No head-nurse or nurse should be out of the hospital before or after the limit of her daily exercise time, two hours, without written permission of the Matron. The Matron, I think, should put the cause and amount of the extension in writing, and report the same to the Treasurer or Chief Officer, at the next general meeting, whenever it is called, of the Officers of the Hospital. She will find this a great protection against petitions. There is not a doubt that the fewer extraordinary absences, the better.