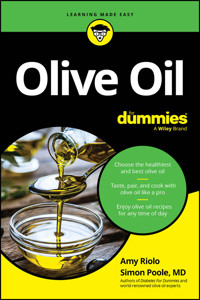

12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Become an olive oil expert with this fun guide

Everyone loves a good bottle of EVOO. That's Extra Virgin Olive Oil, in case you didn't know. Olive Oil For Dummies is full of things you might not know about how to taste, buy, store, and use this incredible—and increasingly popular—oil. Complete with recently discovered health benefits, fascinating history and lore, and mouthwatering recipes, this is the essential guide to understanding everything you need to know about “liquid gold”. You'll learn to tell real olive oil from counterfeit, and how to determine its quality and value as well as recognize the healthiest EVOOs with this trustworthy Dummies guide. Look no further for clear, concise, and accurate information on all things olive oil.

- Discover the history and extraordinary health benefits of olive oil

- Explore the power of anti-inflammatory and antioxidants we call polyphenols

- Learn to avoid fraudulent olive oil and, get the most for your money

- Test your oil to ensure quality and pair flavors with food

- Store olive oil properly and enhance its flavor and nutrients as you cook

- Try authentic, mouthwatering recipes rich in—you guessed it—delicious olive oil

Olive Oil For Dummies is an excellent choice for foodies, olive oil lovers, travelers, home cooks, chefs, medical professionals, and anyone looking to learn the health benefits of olive oil.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Olive Oil For Dummies®

To view this book's Cheat Sheet, simply go to www.dummies.com and search for “Olive Oil For Dummies Cheat Sheet” in the Search box.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

About This Book

Foolish Assumptions

Icons Used in This Book

Beyond the Book

Where to Go from Here

Part 1: Introduction to Olive Oil

Chapter 1: Exploring the Story of Olive Oil

Defining the Olive Tree throughout its History

Recognizing the New World of Olive Oil

Chapter 2: Understanding Olive Oil Classifications

Recognizing the classifications of olive oil

Defining Other Olive Oil Standards

Chapter 3: Appreciating the Production Process

Producing the Best Product

Processing at the Mill

Maintaining “Green” Groves

Chapter 4: Explaining Quality and Comparisons with Other Oils

Recognizing Quality Olive Oil

Testing Criteria for EVOO

Comparing EVOO to Other Oils

Part 2: How Olive Oil Improves Health

Chapter 5: Choosing Healthy Fats

Identifying Different Types of Fat

Determining the Benefits of Eating Healthy Fats

Chapter 6: Incorporating Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Polyphenols

Understanding Polyphenols

Knowing the Extraordinary Polyphenols in EVOO

Chapter 7: Recognizing Olive Oil’s Role in the Mediterranean Diet

Focusing on Olive Oil as the Primary Ingredient

Considering Olive Oil as Medicine

Chapter 8: Maximizing the Health Benefits of Olive Oil

Examining the Benefits of EVOO

Knowing Your Daily Intake

Increasing the Efficacy

Part 3: Incorporating Olive Oil into Your Daily Life

Chapter 9: Tasting Olive Oil Properly

Considering the Flavor Profiles

Working with the Best EVOO

Chapter 10: Deciphering the Taste of Different Varieties

Checking Out Varieties of Olive Oil

Beginning to Combine EVOOs with Foods

Chapter 11: Pairing Extra-Virgin Olive Oil with Food and Wine

Understanding How to Complement Flavors

Pairing EVOO with Food

Matching EVOOs with Wine

Part 4: Choosing Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Chapter 12: Buying Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Deciphering the Labels

Getting to Know Your EVOO

Chapter 13: Recognizing Proper Packaging and Storage

Recognizing a Good EVOO Label

Maintaining EVOO’s Quality

Chapter 14: Purchasing, Price, and Affordability

Prioritizing the Purchase of EVOO

Getting the Most Out of Your EVOO

Part 5: Creating Dishes with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Chapter 15: Cooking, Frying, and Preserving with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Cooking with EVOO for Flavor and Nutrition

Frying in EVOO

Preserving Food in EVOO

Chapter 16: Baking and Pastry-Making with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Swapping Out Butter for EVOO

Choosing EVOO for Breads and Sweet Treats

Part 6: Cooking with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Chapter 17: Base Recipes

Chapter 18: Breakfast and Brunch

Starting Your Day with a Shot of EVOO

Working EVOO into Your Morning Routine

Chapter 19: Appetizers

Chapter 20: First Courses

Chapter 21: Second Courses

Chapter 22: Desserts

Part 7: Diving Deeper and the Future for Olive Oil

Chapter 23: Enrolling in Tasting/Sommelier Classes and Oleo Tourism

Tasting at a Whole New Level

Discovering Oleo Tourism

Chapter 24: The Future of Olive Oil

Cultivating Better Production and Quality

Spreading the Great News of EVOO

Part 8: The Part of Tens

Chapter 25: Ten Other Uses for Olive Oil

Bathing in olive oil

Removing Makeup

Glossing and Nourishing Your Hair

Shaving Oil

Making Facial Masks

Treating Your Hair

Exfoliating Your Skin

Conditioning Your Hands

Moisturizing Your Skin

Cleansing Makeup Brushes

Chapter 26: Ten Easy Ways to Consume More Extra-Virgin Olive Oil

Cooking with EVOO

Drizzling for Added Flavor

Prioritizing Your Health

Eating More Vegetables and Salads

Consuming EVOO throughout the Day

Substituting with EVOO

Introducing Children to EVOO

Exploring New Tastes and Varieties

Redefining the Value of EVOO

Continuing Your Journey through Travel

Appendix A: Metric Conversion Guide

Index

About the Authors

Supplemental Images

Connect with Dummies

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Chapter 7

TABLE 7-1 Mediterranean Diet Adherence Scoring System

Chapter 9

TABLE 9-1 Flavors of a Group of Polyphenols: Secoiridoides

Chapter 10

TABLE 10-1 How to Use Different Intensity Oils

Chapter 11

TABLE 11-1 Flavor Categories of EVOOs

TABLE 11-2 Food Combinations with EVOOs

Chapter 15

TABLE 15-1 Oil Temperatures and Cook Times for Deep-Frying

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

FIGURE 1-1: An ancient press in Volubilis, Morocco.

FIGURE 1-2: An Ancient Greek amphora depicting olive harvesting.

FIGURE 1-3: Amy with “the sacred trees of Athena,” Acropolis, Athens.

FIGURE 1-4: Olive groves painting by Vincent van Gogh.

FIGURE 1-5: Map of latitudes where olive trees thrive.

FIGURE 1-6: An olive grove in the Cape area of South Africa.

Chapter 2

FIGURE 2-1: The NAOOA quality seal.

FIGURE 2-2: Example of DOP logo used by member growers in the region of Granada...

Chapter 3

FIGURE 3-1: The production process.

FIGURE 3-2: Harvesting by modern machine.

FIGURE 3-3: Harvesting by hand in a UNESCO heritage site.

FIGURE 3-4: A model of traditional milling methods.

FIGURE 3-5: Modern milling and production.

FIGURE 3-6: Extra-virgin olive oil preserved in storage tanks.

Chapter 6

FIGURE 6-1: Oxidative stress in a cell.

Chapter 7

FIGURE 7-1: Tenute Cristiano farm in Calabria, Italy.

Chapter 8

FIGURE 8-1: Polyphenols in extra-virgin olive oil.

Chapter 9

FIGURE 9-1: Olive oil assessment form.

FIGURE 9-2: How a professional olive oil sommelier tastes EVOO.

FIGURE 9-3: A spider chart illustrating different flavors of EVOO.

Chapter 12

FIGURE 12-1: A bottle collar for an extra-virgin olive oil.

Chapter 13

FIGURE 13-1: Olive oil bottles on store shelves.

Chapter 23

FIGURE 23-1: Tasting Room at the Olive Oil House, Corfu Town

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Begin Reading

Appendix A: Metric Conversion Guide

Index

About the Authors

Pages

i

ii

1

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

Olive Oil For Dummies®

Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Media and software compilation copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FURTHER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFORMATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE. FURTHER, READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT INTERNET WEBSITES LISTED IN THIS WORK MAY HAVE CHANGED OR DISAPPEARED BETWEEN WHEN THIS WORK WAS WRITTEN AND WHEN IT IS READ.

For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 877-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002. For technical support, please visit https://hub.wiley.com/community/support/dummies.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024946944

ISBN 978-1-394-28286-9 (pbk); ISBN 978-1-394-28288-3 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-394-28287-6 (ebk)

Introduction

La produzione dell’olio non è solo un mestiere, è una tradizione. L’oliva non è solo un frutto: è una reliquia. (The production of olive oil isn’t only a profession, it’s a tradition, the olive isn’t only a fruit: its an heirloom.)

—PREDRAG MATVEJEVIC, BREVIARIO MEDITERRANEO (GARZANTI LIBRI)

Olives are the ingredient most commonly associated with the Mediterranean diet — and that’s for a good reason! There are more than 950 million olive trees are in the region, comprising the majority of the world’s total. It is said that 25 to 40 percent of the daily caloric intake of people in the Mediterranean region has traditionally come from olive oil.

To us, olive oil is much more than a favorite culinary ingredient to savor and promote, it’s truly liquid gold — brimming with tradition, history, lore, and nutrition. Olive oil is a common bond that unites the people of the entire Mediterranean region not only to each other, but also to the world at large. In addition to being the fat of choice that we use to cook with, good-quality extra-virgin olive oil is essential in our personal care and health rituals as well. Our shared passion for the olive fruit has given olive oil a starring role in both of our careers and led us to begin working together years ago. We’ve both written on the topic extensively in our previous works as well as our trilogy of diabetes books for the For Dummies series and are known as worldwide experts on the topic. (Additionally, Simon is an international authority, teacher, and medical consultant on olive oil; and Amy has her own brand of private label olive oil and co-leads cuisine and culture tours to olive-producing countries.)

Olive trees are an especially important form of cultural heritage which ties us to the land, our ancestors, and future generations while providing shade, beauty, industry, and good health. While giving a joint presentation on the role of extra-virgin olive oil and the Mediterranean Diet in preventing and treating diabetes, we laid the foundation for a professional partnership that would allow us to discuss not only a favorite topic, but also the keys to cooking and living with both pleasure and health in mind.

About This Book

People all over the world are beginning to value olive oil’s unique and extraordinary place in the Mediterranean diet and embrace its exquisite flavors and powerful health benefits. According to data from the European Commission, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the International Olive Council, olive oil is one of the fastest growing global industries, and the United States is the second largest consumer in the world.

The key to getting the most from the juice of the fruit of this ancient tree is through understanding its past and learning about the extraordinary gifts of the most precious extra-virgin olive oils. Unfortunately, there are still a lot of myths and a shroud of mystery surrounding the consumption of olive oil and the industry at large. In Olive Oil For Dummies, we demystify recent clinical research about the nutritional properties of olive oil and clearly explain its ingredient-specific terminology as well as how to incorporate more of it into our daily meals and get the most nutritional value from it as possible.

Researchers are concluding that the most important and exciting health-giving constituents, found only in extra-virgin olive oil, are the unique and abundant antioxidant polyphenols of the olive fruit. These fascinating compounds, produced by the tree as defense in its challenging environment, also have profound protective effects on our health. In Chapter 6, we explore the story of polyphenols in depth, helping you to understand how to recognize and taste the power of polyphenols.

A few of the potential health benefits of consuming extra-virgin olive oil, as we explain in Part 2, include its association with:

Reducing the risk of heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis; breast, colon, and bowel cancer; and the incidence of melanoma, memory loss, and dementia in old age

Boosting the immune system against the negative effects of toxins, microorganisms, parasites, and other foreign substances

Increasing healthful gut bacteria and nutrient absorption in food

Nowadays, most people have a difficult time choosing which olive oil they should use. Complicated labelling terms, high prices, country of origin information, and lack of knowledge make it really difficult for consumers to make educated decisions. In Part 4, we discuss everything that you need to know to understand the labels, ensure proper packaging and storage, and make the best purchasing decisions for your health and wallet.

In Olive Oil For Dummies, you’ll discover how to recreate crave-worthy olive oil–based dishes from morning to noon to night. Whether you’re in the mood for breakfast, lunch, an appetizer, or a dessert, you’ll enjoy delicious, time-honored tastes that are perfectly suited to the modern palate. Each of Amy’s recipes offer pairings of delicious dishes with specific types of olive oil and wine. You’ll also find wholesome and tasty base recipes that are rich in olive oil to elevate your daily cooking. With increasing amounts of great olive oils available around the world, it’s the perfect time to share the tips that will enhance flavor, nutrition, and variety in our diets. We’ll also show you how to properly taste and test olive oil to ensure quality, freshness, and flavor.

Ever wondered how quality olive oil is produced? We take you behind the scenes of the world’s artisan producers so that you can learn classifications and definitions while appreciating the production process. Olive Oil For Dummies also demystifies how to decipher the appearance and taste of the most widely available types while explaining the importance of their terroir (the soil, environment, and climate where the olives are grown). Finally, you’ll witness the life-affirming role that olive oil plays in the livelihood of its producers and native regions while being inspired to take full advantage of its bounty yourself.

Foolish Assumptions

This book assumes that you know nothing about olive oil, nutrition, and cooking with it, so you won’t have to face a term that you’ve never heard of before and that isn’t explained. For those who already know a lot about olive oil, you can find more in-depth explanations in this book as well. You can pick and choose how much you want to know about a subject, but the key points are clearly marked. You may also assume that it will never be an easy task to select the best olive oil, get the most value for your money, and cook all sorts of new recipes with it. Each chapter will help you to find everything that you need to know in order to enjoy olive oil, prepare better tasting food, and discover optimal health.

Icons Used in This Book

The icons alert you to information you must know, information you should know, and information you may find interesting but can live without.

When you see this icon, it means the information is essential and you should be aware of it.

This icon marks important information that can save you time and energy.

We use this icon whenever we tell a story based on our personal experience.

This icon is used to help you with medical advice about the choices you have to optimize your treatment.

This icon gives you technical information or terminology that may be helpful, but not necessary, to your understanding of the topic.

This icon warns against potential problems (for example, things to avoid when buying, purchasing, storing, or cooking with extra-virgin olive oil).

Finally, a little tomato icon () is used to highlight vegetarian recipes in the Recipes in This Chapter lists, as well as in the Recipes at a Glance at the front of this book.

Beyond the Book

In addition to the content of this book, you can access some related material online. We’ve posted the Cheat Sheet at www.dummies.com. It contains important information that you may want to refer to on a regular basis. To find the Cheat Sheet, simply visit www.dummies.com and search for Olive Oil For Dummies cheat sheet.

Where to Go from Here

Where you go from here depends on your level of interest and passion. Personally speaking, we never tire of learning more about olive oil. If you already have basic knowledge of olive oil and want to know more about labeling regulations, go to Chapter 13. If you’re a novice, start at Chapter 1. If you want to know more about how to cook with extra-virgin olive oil, go to Chapters 17 through 22. Chapter 14 helps you determine how to get the most value for your money. You may have specific interests at different times, so check the Table of Contents to find what you need rapidly.

The wonderful world of olive oil is steeped in history, tradition, and lore as well as science, modern industry, and technology trends. Go at your own pace and enjoy the process. Remember that like extra-virgin olive oil, learning new information also helps to keep us healthy.

Part 1

Introduction to Olive Oil

IN THIS PART …

Discover the history of olive oil.

Examine olive oil classifications and standards.

See how the production process works.

Find out what makes a quality extra-virgin olive oil in order to avoid fraudulent or defective products.

Chapter 1

Exploring the Story of Olive Oil

IN THIS CHAPTER

Examining the ancient origins of olive oil

Discovering how olive oil has been used in food, medicine, spirituality, and culture

Understanding the evolution of olive oil in modern times

To understand what the olive tree and olive oil means to people who have grown up in its shade, it’s important to know how the tree and its fruit have shaped the lives and cultural heritage of their ancestors. The olive tree is deeply rooted in the landscape and the traditions of the Mediterranean regions where it has flourished for millennia, and its history is deeply intertwined with the development of human civilization.

Throughout history, olive oil as a culinary ingredient was of great importance in cooking, and its health benefits were very much valued. In addition to olive oil, other olive products are also found in the entire region. Olives, olive wood, and olive pomace are used to make everything from food and furniture to fuel and soap.

This chapter journeys across time and continents to explore the history and significance of olive oil. It explains how olive oil has been used in food, medicine, and culture historically and in modern times.

Defining the Olive Tree throughout its History

The history of the relationship between humankind and the olive tree stretches back many millennia. There is archaeological evidence suggesting that people in the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean consumed olives in neolithic times, as well as using the wood for fire. It’s likely that curing or fermenting techniques to reduce the natural bitterness of olives would have been known to communities during this time. Though these processes would be refined and improved particularly in the Roman period, the use of wood ash with brine to cure the fruit to make them more palatable was widespread. By the fourth millennium BCE, there is evidence to show the systematic harvesting and crushing of olives for oil. And by the Bronze Age, this was a well-established technique to produce oil for food, cosmetics, and lamp fuel.

From wilderness to farm

When humans started to farm rather than moving to hunt and gather food about 10,000 years ago, the wild olive tree, probably originating from Persia and Mesopotamia, was among the earliest plant species to be domesticated and planted in the so-called fertile crescent. The fertile crescent included lands that now span from Iran and Iraq to Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine. Archeologists have found olive pits suggesting that that the olive trees in those areas were first domesticated 8,000 years ago. Selective breeding ensured that the hardiest and most productive trees — Olea europaea — survived. Known as the common olive, it’s a variety of an evergreen tree native to the Mediterranean region that is still growing today with its various subspecies and regional varieties.

Farming also allowed people to experiment with new agricultural techniques and improve milling to get the most oil from the olives. Olive presses were larger and became valued and protected resources near to the communities they served. Stone wheels often moved in circles by harnessed donkeys or mules became the most efficient way of crushing the olives ahead of “pressing” them and separating juice (or oil) from the flesh, pit, and skin. Evidence of this method being used dates from 6,000 years ago and widely practiced until the early part of the last century. (An ancient press is shown in Figure 1-1.) Traditionally, each community had its own mill. Locals brought their recently harvested olives to their local mills for pressing. For this reason, there is a deep desire among people in the Mediterranean region to use “their own oil,” even today. People who live in olive-producing areas have long-lasting ties with a local, “trustworthy” mill. They bring their olives to that mill — often watching the oil being extracted — and later with their families enjoy the oil throughout the year. This way they ensure the best quality, flavors of choice, and freshest oil possible.

FIGURE 1-1: An ancient press in Volubilis, Morocco.

There are some olive oils that are still produced using ancient milling techniques. This can produce some good quality oils, but greater care needs to be taken to ensure that it is not spoiled. When visiting olive oil — producing countries, it can be a fun and informative experience to visit both modern and ancient mills. Modern methods of milling are generally much more efficient, protecting and preserving the flavor and health benefits of extra-virgin olive oil. This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3.

Olive trees can live for hundreds, and sometimes thousands of years. In each Mediterranean culture, the ancient trees are viewed with more prestige and importance. There are names in each language specifically dedicated to the trees that are hundreds of years and thousands of years old. Oil that comes from those trees is extremely valuable culturally and commands higher prices when sold. In Italy, for example, secolari is the term used to describe trees that are hundreds of years old and millenari is the word used to describe trees that are thousands of years old. Olive trees are extraordinarily resilient, having adapted to thrive in harsh environments and can produce new shoots even after devastating droughts or fires. It’s extraordinary to think that some trees are so ancient that they date back perhaps three thousand years. Their gnarled massive, beautiful forms are imposing and often are a symbol to local people of their own history and survival.

From ship to shore

In the late Bronze Age, from around 1200 BCE, Phoenician sailors and traders from what is now Lebanon established colonies and trading posts throughout the Mediterranean to North Africa, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula. Historians believe they played an important role in expanding olive cultivation and milling across the Mediterranean. Archeologists often find evidence of olive oil production and typical storage jars called amphorae at sites and in cities that were founded by these masterful merchants and explorers. One of the recipes found in the jars was the now trendy aioli sauce, which Chef Amy teaches you how to make in Chapter 17.

Although they aren’t talked about very often on a daily basis, the Phoenicians’ legacy in spreading the olive tree and its cultivation practices is a testament to their role as key players in the agricultural and economic history of the Mediterranean. Many of the similarities in Mediterranean cuisine are a result of their commercial efforts.

Shaping ancient empires

In cultures such as Ancient Persia, Egypt, Greece, and Magna Grecia in the fourth millennium BCE, olive oil played a vital role as a food and important source of nutrition. It was fundamental to the economy of the expanding empire and was not only a cornerstone of everyday life but also had profound religious and symbolic meaning.

Ancient Egypt

By the fourth millennium BCE, the ancient Egyptians were using olive oil not only for culinary purposes, but also for cosmetics and perfumes. Since perfume making was so important to Mediterranean trade at that time, the role of olive oil in its production made olives an even more significant crop, surpassing even the grape in importance. According to the Egyptians it was the goddess Isis, sister and wife of Osiris, who taught humans how to grow olive trees and extract their oil. The ancient Egyptians cultivated many olive orchards. An inscription on a temple dedicated to the god Ra dating from the twelfth century BCE during the rule of Ramses II describes the olive orchards around the city of Heliopolis producing pure oil, the best quality in all of Egypt, for lighting the lamps in sacred places.

Ancient Greece

During this time, the olive became a more important crop than the grape. Mycenaean tablets mentioning olive trees dating 3,500 years ago were found on the Greek island of Crete along with amphoras at the Palace of Knossos. An example of a Greek amphora is shown in Figure 1-2.

© CPA Media Pte Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

FIGURE 1-2: An Ancient Greek amphora depicting olive harvesting.

In the traditional diet of Crete, where scientists first described the Mediterranean diet, it is said that 70 percent of total fat consumption comes from olive oil. Mediterranean cuisine “swims” in olive oil. The culinary term lathera, translated as “the ones with oil,” is a traditional Greek cooking method and category of dishes. The dishes are integral to the Mediterranean diet and particularly the Cretan diet, being rich in olive oil, often with tomatoes, onions, beans, other vegetables, various herbs and spices, and bread for soaking up the oil. The olive oil not only serves as the cooking medium but also adds significant flavor and nutritional value to the dishes.

Athens was the birthplace for Greek olive oil. Olive tree depictions also decorated the walls of ancient Egyptian and Greek palaces. Olive oil during this time was used as fuel for lamps, to clean and moisturize the body, as well as for a balsam for wounds and in perfumes. Aristotle himself promoted the divine powers of olive oil, using it to anoint himself before he met with his disciples, believing that it would give him increased knowledge and confidence during debates. In Athens, the revered goddess Athena gave the founders of the city the fruit and oil of the olive tree to nourish and sustain them (see Figure 1-3), leading to the creation of an empire as well as the naming of the city.

Ever since, the olive tree was central to the genesis mythology of Athens and also featured large in other legends and tales. In 480 BCE following the battle of Salamis, the general Themistocles recaptured the Acropolis, which had been burned to the ground by the invading Persian army. A sacred tree atop the hill was said to have immediately grown healthy, fresh buds from its charred remains that represented fresh hope and the promise of a bright future to those who rebuilt the city. To the Greek poet Homer, olive oil was nothing less than “liquid gold.”

After thousands of years of promotion by philosophers, gods, goddesses, and demigods alike, olive oil continued to be highly valued and prized throughout the Mediterranean and Asia Minor. In its purest form, it was used as a medicine and food. It also provided health and cleansing of the skin, including bathing rituals of athletes, and could be used as oil for handheld clay lamps, a lubricant and even a base for paints. It was offered to the gods and was central to many religious ceremonies. Victorious Olympic athletes would be adorned with olive leaf wreaths and perhaps even more welcome was the prize of quantities of olive oil worth a small fortune. Olive groves were a common sight in the Greek countryside, and laws were even enacted to protect these valuable trees. The olive branch remains a symbol of peace and prosperity, a legacy that can be traced back to its revered status in ancient Greece. It is extraordinary to think that the oldest living olive tree in Crete is estimated to predate the first ancient games.

FIGURE 1-3: Amy with “the sacred trees of Athena,” Acropolis, Athens.

Physicians and philosophers, including the “father of medicine” Hippocrates, knew of the contribution of olive oil to good nutrition and health, referring to it as “the great healer,” and it was regularly included in recipes and medicines used to cure ailments. Olive oil was also considered to sooth the spirit and calm the mind as well as treat earaches, hemorrhoids, and sunburn; reverse baldness; alleviate the bites of mythical or real sea creatures; and ward off evil spirits.

Aristotle contemporary and philosopher Theophrastus, born in Lesbos, was the first Greek author to write a treatise on the “Maintenance of One’s Body” and in particular on the use of ointments and perfumes. He was the first to coin the term “botany” and understood it as a science that studies plants and their healing power. According to Theophrastus, the unguentum, an ancient Latin word for perfumed ointment, must be composed as follows: a fatty base of animal origin and one of vegetal origin (olive oil); the resin as a fixative; salts; and essences extracted from flower petals with the so-called “Enfleurage.”

Modern medicinal uses of olive oil are considered in Chapter 7.

The Roman Empire

The Ancient Greeks were efficient at producing and using olive oil, but the Romans took it to the next level by increasing production and expanding its use to a much wider area. Feeding the vast empire relied on sophisticated logistics of production and transportation of important staples like grain, wine, and olive oil. In fact, those three items became the pantry staples of what would later become known as the Mediterranean diet. By combining freshly harvested local produce and dairy with grains, wine, and olive oil, the ancients laid the foundation for the world’s healthiest eating plan.

Following Julius Caesar’s return to Rome after defeating his enemies in modern-day Tunisia, the Greek philosopher Plutarch observed that Caesar’s first reaction was to make a speech to the people in order to impress them with his victory. Caesar claimed that he had conquered a country large enough to supply the public every year with 200,000 Attic bushels (an old measurement) of grain and three million pounds of olive oil. Olive oil production on a large scale could generate great wealth and political leverage in Roman times. There were significant advances in the technology of oil production with the emergence of screw presses, the mechanism of which increased pressure and improved yield.

During the latter half of the first century CE, Pedanius Dioscorides, a military physician under the Roman Emperor Nero, known as the “father of pharmacognosy,” (the study of medicines from natural sources), advocated the use of the early harvest, bitterest, “greenest” olive oil for conditions that may have had an inflammatory basis. This ancient doctor did not apply modern medical methods to prove his beliefs, but it can be observed that his oil was likely to be richest in anti-inflammatory compounds, which is discussed in detail on Chapter 6.

The Romans were experts in agriculture and the writer Pliny the Elder in his book Natural History described the way in which olives should be grown and even categorized olive oil according to quality in a classification, which is quite similar to modern chemical and sensory grading. Coincidentally, the oldest preserved olive oil in the world, now in a museum on Naples, was discovered close to where the author met his death in the devastating eruption of Vesuvius at Pompeii in 79 CE.

At the time, the city of Naples was heavily influenced by Greek culture. Nero used to recite in Greek, not Latin, in Rome’s amphitheaters, and writers of the time dubbed it as a city in which “one could live and die in the manner of the Greeks.”

Religious and culinary influences

In the Mediterranean, the ancient traditions of using olive oil as a healthy food continued alongside the symbolic and cultural importance of the olive tree in religion and culture. Olive oil and the olive tree had an important place in ceremonies and mythology, including giving the strength to Hercules, not least in his fearsome club of olive wood. The olive leaf and branch continued to have symbolic meaning, including signifying peace and hope.

The topic of the historical religious appreciation of olive oil deserves a book of its own, as olive oil has a revered position in three monotheistic faiths — Christianity, Judaism, and Islam — as well as in ancient worshipping traditions. The Bible refers to the olive tree as “the key of trees” and the “tree of life.” It is mentioned on numerous occasions in the Qur’an and the Bible. From an olive branch brought by a dove as a sign of peace to Noah in the Old Testament, to events on the Mount of Olives in the New Testament, and the description of the olive representing the gifts of variety and abundance in the Qur’an, the olive tree has a special and sacred status to many people of faith.

The reason why olive branches were used as symbols of peace in the Mediterranean since antiquity is because it took 20 years for them to bear fruit. Olive trees weren’t planted in areas where people couldn’t establish long-term settlements (meaning areas of conflict). For this reason, olive trees became associated with peace from a practical sense as well as a spiritual one. Hanukah commemorates the miracle of one day’s worth of olive oil lasting eight nights as recorded in the Talmud. Christians use olive oil to consecrate crowned rulers and church dignitaries. According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet Muhammad is said to have proclaimed, “Take oil of olive and massage with it. It is a blessed tree.” In antiquity, olive oil was coveted as an ointment, fragrance, and an essential element of religious ceremonies in addition to its flavor and nutritional uses.

PROTECTING A CENTRAL MILL BEHIND STONEWALLS

The value of olive oil in antiquity can’t be overstated. A few years ago, a local farmer in a remote part of Jordan was expanding his olive grove on a high plateau when he came across stonework, which was obviously of great historical importance. Archeologists from the capital Amman, in partnership with the British Museum, soon established this site to be a significant, heavily defended and protected structure dating back to the Bronze Age — 4,500 years ago. This seemed odd because it was known that at that point in history, raids by the Egyptians had decimated large settlements in the area, the result of which was “urban collapse” and the retreat of populations to rural areas.

Living in smaller, scattered locations reduced the likelihood of attack, so there was less need to build thick walls for defense. The walls here seemed to be different, and as the soil was carefully removed, it became apparent that this was an ancient olive press for the area. No doubt, bringing large quantities of harvested olives over the space of a few weeks to a central mill for the production of valuable olive oil made it a very real target for attack. It’s easy to imagine people in those ancient times bringing their precious fruit to a place of safety for the production of olive oil, reassured as they made their way up the hill past heavily armed guards and the solid walls of the olive mill.

Northern and Central European writers and artists began documenting olive trees in their famous works during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Featured in the poetry of Wilde and Yeats and the paintings of leading artists, the allure of olive trees could not be ignored. Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch post-impressionist painter, held a deep fascination and reverence for olive trees, for whom they held a sense of history and awe (see Figure 1-4). He struggled to capture their intricateness and beauty, especially the shimmering silver of the underside of the leaf.

© dbrnjhrj/Adobe Stock

FIGURE 1-4: Olive groves painting by Vincent van Gogh.

Much of what we know about olive oil and the deepening of its usage is due to the many Muslim Caliphates and empires that ruled in the Mediterranean.

There are many surviving Medieval Arabic culinary texts that provide a wealth of knowledge into this much overlooked area of Mediterranean culinary history by the West. During the Medieval period it is the reign of the Abbasid Caliphate, which set trends from Baghdad to modern Spain. In fact, the palace meals were so lavish during the time that the Muslim prince Abd al-Rahman hired his chief cook and trendsetter, nicknamed Ziryab, to bring his knowledge and insights to the courts of Andalusia in the ninth century CE. Thanks to Ziryab, whose real name was Abu al-Hasan, Andalusia gained music (he was credited for inventing the lute), fashion styles, rich garden architecture, numerous elevated recipes, and “new” ingredients such as rice, saffron, spices, and hibiscus procured from Egypt.

When combined with the olives and olive oil tradition already deeply rooted in Spain thanks to the Romans, Medieval Spanish and practices introduced from Iraq, as well as the cuisine of the lands under their empire, gained many layers of flavor and intricacy. Marinated olives in herbs were served on the table of Ibrāhīm ibn al-Mahdī, an eighth century CE Abbasid prince, singer, composer and poet, just as they are served across the Mediterranean today. The Abassid caliphate based much of their cuisine on the Persian tradition. Vegetables sautéed in olive oil and then finished off with vinegar were very popular at the time. The Bedouin method of roasting lamb in olive oil also continued to flourish. Simple recipes for items such as bulgur with lentils, garlic sauce, chicken with olives, and meat and stuffed olive stew used at least ¼ cup of olive oil for a recipe that serves four. Original Moroccan recipes for tajines with vegetables such as cardoons (similar flavor to artichokes) were created to test the quality of the new olive harvest.

In the tenth century, for example when Fatimid rulers from modern-day Tunisia ruled from Sicily and Tunisia and as far East as Mecca, they used to promote cross-cultural religious festivities. They would encourage people of all faiths to come out and partake in the merrymaking of religious festivities of their neighbors. Because of the multi-religious populations of the Mediterranean region, which were ruled by different groups, cooking with olive oil continued to be a way in which to create cuisine that could be enjoyed by all. During Orthodox fasting periods, for example, animal fat is prohibited and meals that were once cooked with meat or animal fat were now replaced with olive oil. The Jewish community also embraced these dishes because they were meat-free options, ensuring that no non-kosher animal products were part of the dishes.

Court rulers who held dinners for large multi-national organizations needed to ensure that all of their guests could partake in the lavish foods that they were serving, despite their religious origins. By the end of the Ottoman Empire (fifteenth through nineteenth centuries CE) an entire category of olive oil–based dishes called Zeytinyağlı emerged and is still popular in modern Turkiye today. In fact, internationally acclaimed chef, humanitarian, and restaurateur José Andrés named one of his restaurant concepts Zaytinia in Washington, DC, after it.

The most popular of these olive oil–laden dishes that graced the tables of Ottoman palaces included artichokes and string beans braised in olive oil. While the ingredients are few, it is the manner of cooking the vegetables that makes them “sing.” And modern Turkish cooks follow strict guidelines in order to make the recipes live up to their legacy. Sometimes rice and tomatoes are added to the dishes, and they are usually served at room temperature. Garnished with dill or parsley, these recipes are still a testament to Medieval cooking and the capacity for food to be both delicious and nutritious. Vegetables, legumes, grains, cheese, and extra-virgin olive oil continued to nourish and entice palates and feed the masses in the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages as in ancient times.

Recognizing the New World of Olive Oil

With the “discovery” of the Americas by ships launched from Spain and Portugal came a new chapter in the expansion of the olive tree. Those who love the olive tree and olive oil and who inhabit parts of the world with a climate similar to the Mediterranean have for centuries experimented with growing and harvesting its fruit in new regions. In general, this hardy tree can survive and flourish where summers are hot and dry, with mild and often wet winters. Although there will always be localized variations in climate, these conditions are often found between 30- and 45-degree latitudes both north and south of the equator as shown in Figure 1-5.

Groves going west

In the sixteenth century the great powers of Spain and Portugal began to explore and colonize the Americas. Early settlers in Argentina, Chile and Peru found the climate in the Southern Hemisphere conducive to agriculture they were familiar with at home and brought with them vines for wine cultivation and olive trees for olives and olive oil. The first olive cuttings were brought to California in the late eighteenth century by Franciscan missionaries. More recently, olive oil production has expanded to other regions including Florida and Texas in the United States, and countries like Uruguay, Brazil, and Mexico in Central and South America.

FIGURE 1-5: Map of latitudes where olive trees thrive.

Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, encountered olive oil during his time as a diplomat in Southern France and considered the olive tree to be “surely the greatest gift of heaven.” He was also an advocate of excellence in nutrition. Unfortunately, the climate thwarted his attempts to establish a working olive grove at his Monticello estate in Virginia.

Nowadays the California olive oil industry has emerged as a major player in the global marketplace. Olive oil is one of the most important of the state’s 350 agricultural products. According to the California Olive Council, the modern industry includes 75 different varieties of olives. Known for having a great variety, creative blends, and tasty flavor profiles, the unique terroir (soil, environment, and climate) of Californian olive oils distinguishes them from oils made of the same varieties in other places. Despite the large amount of olive oil that California produces, American demand is still far greater than the supply, making it necessary to import olive oil from the Mediterranean region and from other areas of the world.

Expansion into Asia and beyond

The expansion from traditional growing areas in the Mediterranean to South and East Asia is a more recent phenomenon, mainly occurring in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

India has seen experimental and commercial planting of olive trees, especially in the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat. The initiative, often supported by collaboration with experts from established areas of production, aims to tap into the growing domestic demand for olive oil in India and explore export possibilities. China has also embraced olive cultivation, with regions like Sichuan province becoming centers for olive production.

The Japanese consume more olive oil per person than other Asian countries. This is mainly imported. However, there is some local production which began in 1908 on the island of Shodoshima in the Seto Inland Sea, which enjoys a moderate climate that allows olive cultivation.

Regions with a climate similar to the Mediterranean are often suitable for wine production, and so it is no coincidence that the cultivation of vines and olive trees often goes hand in hand. Australia and New Zealand, with vast areas of land potentially available, are now not only famous for large scale production of wines, but also production of high-quality olive oil. Olive oil production on this scale has been introduced relatively recently in comparison to winemaking, but the 1990s saw significant planting and investment in large scale facilities for olive oil production.

Olive oil in Africa

Countries on the North Coast of Africa bordering the Mediterranean Sea, including Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Libya were central to the early story of olive oil cultivation and production and its story is included in our narrative above.

In the Southern Hemisphere, African olive oil production is a more recent development.

The first recorded attempt at olive oil production in South Africa dates back to the sixteenth century, when Jan van Riebeeck, commander and founder of Cape Town, in 1655 attempted to produce foods that would sustain Dutch trading ships sailing around the Cape of Good Hope to the Dutch East Indies. However, it wasn’t until much later, in the nineteenth century, that olive cultivation became more established in South Africa, with several farms in the Paarl and Stellenbosch regions planting olive trees, resulting in the wine and olive route journeys possible today (see Figure 1-6).

FIGURE 1-6: An olive grove in the Cape area of South Africa.

Chapter 2

Understanding Olive Oil Classifications

IN THIS CHAPTER

Examining the different types of olive oil

Knowing what is considered extra-virgin olive oil

Exploring marks of quality

Determining quality olive oil is one of the most difficult tasks for consumers. One of the first questions people usually ask about olive oil is the difference between olive oil and extra-virgin olive oil. This chapter will help you understand the distinctions between the categories of olive oil and to appreciate the difference this makes to the taste and health benefits. The criteria for each category are explored in this chapter, with more details on testing and regulation in Chapter 4.

It is not known when the term virgin was first used to describe olive oil, but it refers to an uncontaminated and unadulterated quality, with extra virgin suggesting even more purity. Other standards are applied in certain growing regions to denote the origin of an olive oil or its organic credentials, which may not directly affect the taste of an oil. However, the standards may reflect a commitment to authenticity and responsible farming practices.

Other than aged balsamic vinegar of Modena (the highest grade of balsamic vinegar), extra-virgin olive oil is perhaps one of the longest terms to describe a single food. For reason of convenience, it is often referred to as EVOO.

Recognizing the classifications of olive oil

In any supermarket or delicatessen, you are likely to see rows with several different bottles of olive oils. There may be lots of information on the label, the details of which are considered in more detail in Chapter 12. The largest letters will usually tell you that the product is “olive oil” or “extra-virgin olive oil.” Most producers aim for the higher standard of extra-virgin oil, which means “virgin olive oil” is less commonly produced. It turns out that there is a very big difference between these terms when it comes to what is in the bottle.

Olive oil categories

The classifications of olive oil are a formal series of definitions, which have been globally established by the International Olive Council (IOC) and by the Codex Alimentarius. The IOC is responsible for promoting olive oil industries worldwide, and its membership consists of major olive-producing countries.

It sets standards for quality, facilitates international trade, and ensures the authenticity of olive products. The Codex Alimentarius, or “Food Code,” is a collection of international food standards, guidelines, and codes of practice adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC). The CAC is the central part of the “Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme” — established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) — to protect consumer health and promote fair practices in food trade.

Each of the categories are different due to their production methods, which are explored in more detail in Chapter 3. But the most important criteria relate to chemistry and flavor, the latter of which is known as its sensory or organoleptic profile (appearance, flavor, mouthfeel, or aroma). The categories for olive oil are the following:

Extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO):

Extra-virgin olive oil is the oil obtained from the fruit of the olive tree solely by mechanical or other physical means under specific conditions — particularly temperature conditions — that do not lead to alterations in the oil. The olive oil doesn’t undergo any treatment other than washing, crushing,

malaxing

(kneading and mixing the olives), centrifugation, decantation, and/or filtration. Among other analytical requirements, extra-virgin olive oil must have an acidity level of no more than 0.8 percent and no

organoleptic

defects (detected through taste or smell). People in the Mediterranean region prefer high-quality olive oils, containing much lower levels of acidity at 0.3 percent or less, for themselves and their families to consume.

Virgin olive oil (VOO):

Similar to extra-virgin olive oil, virgin olive oil is produced by mechanical means without the use of heat or chemicals. However, it has a slightly higher tolerance for many analytical requirements including an acidity level, up to 2 percent, and may not meet the same sensory standards as extra-virgin olive oil.

Olive oil (OO):