Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: Emma Press Children's Fiction Books

- Sprache: Englisch

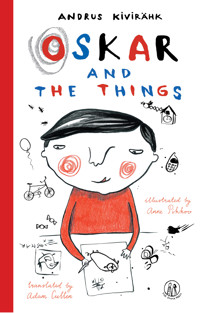

One summer, when both his parents are away for work, Oskar is sent to the countryside to live with his grandma. A dreary prospect turns into disaster when Oskar realises he left his mobile phone back at home. What will he do all summer now? Lonely and bored, Oskar crafts a phone out of a block of wood he finds in the shed and uses it to pretend to call things. To his surprise, the things reply! He speaks to a tough-talking iron, a poetising bin, a bloodthirsty wardrobe, a red balloon that gets tangled in the crown of a birch tree, and many more. Oskar finds himself in high demand, helping the things solve their problems and achieve their dreams. Oskar and the Things is a charming book about the power of the imagination and friendship, by Estonia's leading children's writer, Andrus Kivirähk. With a lively translation by Adam Cullen, and the original illustrations by Anne Pikkov, it is the perfect gift for an introverted child with a rich inner life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 316

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MORE CHILDREN’S BOOKS IN TRANSLATION FROM THE EMMA PRESS

CHAPTERBOOKS

The Adventures of Na Willa, by Reda Gaudiamo, illustrated by Cecillia Hidayat. Translated from Indonesian by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Kate Wakeling.

The Girl Who Learned All the Languages Of The World, by Ieva Flamingo, illustrated by Chein Shyan Lee. Translated from Latvian by Žanete Vēvere Pasqualini.

POETRYBOOKS

Poems the Wind Blew In, by Karmelo C. Iribarren, illustrated by Riya Chowdhury. Translated from Spanish by Lawrence Schimel.

Super Guppy, by Edward van de Vendel, illustrated by Fleur van de Weel. Translated from Dutch by David Colmer.

Everyone’s the Smartest, by Contra, illustrated by Ulla Saar. Translated from Estonian by Charlotte Geater, Kätlin Kaldmaa, Richard O’Brien.

The Book of Clouds, by Juris Kronbergs, illustrated by Anete Melece. Translated from Latvian by Māra Rozīte and Richard O’Brien.

PICTUREBOOKS

The Bicki-Books 1-12, translated from Latvian by Kate Wakeling, Žanete Vēvere Pasqualini, Uldis Balodis and Kaija Straumanis.

When It Rains, by Rassi Narika. Translated from Indonesian by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Emma Dai’an Wright.

The Dog Who Found Sorrow, by Rūta Briede, illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa. Translated from Latvian by Elīna Brasliņa.

Queen of Seagulls, by Rūta Briede. Translated from Latvian by Elīna Brasliņa.

The translation and publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the Traducta programme of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia.

THEEMMAPRESS

First published in Estonia as Oskar ja asjad by Film Distribution in 2015.

First published in the UK in 2022 by The Emma Press Ltd.

Original text © Andrus Kivirähk 2015.

Cover and interior artwork © Anne Pikkov 2015.

English-language translation © Adam Cullen 2022.

English-language text edited by Kate Wakeling.

All rights reserved.

The right of Andrus Kivirähk, Anne Pikkov and Adam Cullen to be identified as the creators of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-912915-78-1

EPUBISBN 978-1-915628-07-7

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

The Emma Press

theemmapress.com

Birmingham, UK

1.

Grandma sat at one end of the table and Dad at the other. Oskar was sitting between them. They were all having meatball soup.

Oskar always enjoyed meatball soup, and not just because he liked the taste. It could be fun! Pea soup is nothing but green mush, so you have to try hard to make it interesting. Whenever Oskar ate pea soup, he imagined a bottomless swamp bubbling in the bowl before him. With his spoon as a shovel, he had to empty the swamp to find the treasure hidden deep beneath it. Slurping up the swamp would also reveal sunken skeletons and swamp monsters, startled by the cosy green muck suddenly disappearing around them.

There weren’t really any monsters or skeletons or hidden treasure lying beneath the pea soup, of course. Oskar knew that, but eating is much more fun when you imagine things!

Meatball soup was one of Oskar’s favourite meals because the stars of the show stood out so well among the vegetables. He would pretend they were chubby sea lions paddling between orange and white icebergs, which is to say between the carrots and potatoes. Orange icebergs don’t really exist, but that didn’t matter – they could always swim in Oskar’s pretend sea! Oskar himself was like an arctic pilot wheeling around in the sky above. The sea lions did try to hide between the icebergs, of course, but they couldn’t evade Oskar’s sharp eyes. He scooped the icebergs up one after another until, in the end, the sea lions found themselves alone in the water with nowhere to hide. Then Oskar would pluck them up and take them to the zoo. Well, okay – he actually just devoured them too!

Today, however, Oskar didn’t have an appetite for meatball soup. The sea lions could carry on feeling relatively safe and secure among their icebergs. He had stuck his spoon into the soup but wasn’t eating – more trying to push all the meatballs to one end of the bowl.

‘Please eat, Oskar. Don’t poke at your food,’ Dad said.

‘Yeah, yeah,’ Oskar sighed, starting to arrange them into rows.

‘How can that mother of yours just up and go to America for two whole months?’ Grandma tutted. ‘Dearie me – that’s nearly the whole summer!’

‘She’s taking classes there,’ Dad said evenly, ‘and that’s just how long they take. What else could we do? America is so far away – you can’t just fly home for the weekend, you know.’

‘But did she have to go all the way out there?’ Grandma grumbled.

‘Yes, she did,’ Dad said, with a little note of irritation creeping into his voice. ‘She’s studying.’

‘All people ever do these days is study, study, study,’ Grandma said. ‘Back in my day, kids would study while adults went to work.’

‘Well, as you can see, I do go to work,’ Dad retorted. ‘And that’s why I’ve brought Oskar here to stay with you.’

‘And I’m very glad you did!’ Grandma exclaimed. ‘I’m happy to have him here with me. It’s just a shame that you can’t stay too. It’s a wonderful chance to have a holiday with your son.’

‘I can’t right now – I don’t have any days off till August,’ Dad sighed. ‘You know that. We’ve been through this several times already. Oskar’s mum will be back by then too, and then we’ll all take a trip together. That’s right, isn’t it, Oskar? And you’ll have a great time out here in the country in the meantime!’

Oskar didn’t say anything; he just kept stirring his soup. He was far from convinced that being out in the country was such a great thing, especially without his mum and dad around. He’d stayed at his grandma’s house before, of course, but not very often, because she lived at the other end of the country and it was a very long drive. They travelled there once every summer and always stayed the night – but those times, his mum and dad didn’t leave without him. This time, he had to stay with Grandma all by himself, and it felt a little scary. What was he going to do all summer?

‘We left my phone behind,’ Oskar said softly.

‘Yes, you told me already,’ Dad said. ‘Why didn’t you remember to bring it, then? I asked if you’d packed everything you needed.’

‘I forgot,’ Oskar mumbled.

‘Not to worry – I’ve got a telephone here too!’ said Grandma reassuringly. ‘You can use it to call your dad if you start to miss him.’

Again, Oskar didn’t reply. Grandma wouldn’t understand that his phone wasn’t meant for calling people so much as it was for playing. He had masses of good games on his phone and was already missing them. Soon Dad would be driving home, leaving him all alone with his grandma – and for two whole months! If he at least had his phone, then he could curl up in a corner somewhere and tap away at the screen to pass the time. At least he’d have some form of entertainment. But now... Oskar felt the tip of his nose getting heavy and the muscles between his eyes starting to tighten, the way they did before tears started to come.

Dad shot him a sympathetic look.

‘Come on, now,’ he said, ruffling Oskar’s hair. ‘It won’t be so bad. I lived in this house for my whole childhood, and I didn’t have a mobile back then, either – nobody did. And I didn’t have any brothers or sisters to play with. But I still had lots of friends, anyway! There are other houses around here and there should be some kids around too. I bet you’ll make friends in no time and you’ll be so busy running around with them that when Mum and I come to pick you up in August you won’t want to hear a word about driving back to the city. When I was little, I couldn’t even find the time to come inside and eat. We went exploring in the woods and the fields, built forts, kicked a ball around, went fishing, and came up with all sorts of other fun things to do. You’re going to have a wonderful time, trust me!’

‘The countryside is the perfect place for children in summer,’ Grandma chimed in.

Oskar just glared at his soup. Dad hadn’t cheered him up – quite the opposite. Grandma had her quirks, but at least he knew her quite well, and he’d been to her little cottage several times before so it felt at least a bit cosy and familiar. But complete strangers from random houses nearby, and the unfamiliar fields and forests – those were downright terrifying!

It was just like any time he had to go to the doctor to get a jab – there’d be this awful feeling in the pit of his stomach that morning at home. Even more terrible was knowing that there was nothing he could do about it – there was no way out and he simply had to accept his fate, get dressed, and climb into the car to go to the clinic, even though it was the very last thing he wanted to do.

Oskar was wrestling with a similar uneasy feeling right now – that his dad’s car would have barely made it off the drive before those kids from the village would come crawling out of the woodwork to carry him off to their fort, no matter how hard he struggled. After that, they’d drag him into the woods, and then somewhere else to go fishing, and then to who-knows-what other horrible places. And Grandma wouldn’t protect him at all – she’d just stand on the porch, holding a bucket and nodding in satisfaction: Ah yes, the countryside is the perfect place for children in summer!

Oskar shot his dad a miserable look. Dad tugged on Oskar’s ear.

‘Don’t look so unhappy!’ he said. ‘I’ll call you. And Mum will definitely be calling from America, too. It’s not like she’s underground or up in space, you know – you’ll have plenty of chances to chat to her as well.’

‘Though it is expensive to make calls from America,’ Grandma said. ‘But don’t you worry – Oskar and I will have a fantastic time together!’

Oskar was sure it would be the exact opposite, but he held his tongue. The meatball soup had grown cold and cloudy from him poking at it with his spoon. Oskar stared at the bowl. He didn’t like the soup at all anymore. He didn’t like the kitchen table, or the kitchen itself. Everything felt so grim and gloomy. A fat housefly buzzed around the light-fitting and he saw a dark stain on the wall next to the stove, which he’d never noticed before but now struck him as extraordinarily ugly. And they’re leaving me here for two whole months! he moaned in his head. Oskar felt a giant wave of sadness crash over him, nearly squishing him flat.

‘Would you like some sweets for pudding?’ Grandma asked. She placed a couple of pieces of hard caramel on the table – the exact kind of treat that Oskar refused to ever stick in his mouth.

‘I’m not hungry,’ he muttered. What else could he have expected! His whole summer was going to drag on forever, surrounded by those flavourless caramels.

2.

Dad left. Oskar and his grandmother stood on the doorstep and waved to him as he drove away. Grandma was holding a tea-towel that she swung over her head so Dad could spot them from the far end of the road. Oskar barely wiggled his fingers. What good was waving? It wasn’t going to bring him back!

‘Well, well, Oskar, dear,’ Grandma said when Dad’s car had disappeared from view. ‘Now it’s just the two of us. You go off and play. I’ve got some jobs to do in the garden and vegetable patch, but you can do whatever you please. Don’t worry – I’m not going to make you work, too! When can kids be free if not in summertime? Once autumn arrives you’ll be off to school, and that’s when the real work begins. Make the most of this last free summer.’

With that, Grandma gave Oskar an encouraging nod and strolled off to the vegetable patch, swaying slightly as she went.

Oskar was left alone. Go and play? Easy for her to say! What was he supposed to play with when he’d left all his toys behind in the city? Even his phone! How could he have forgotten it? What an idiot he was! He’d put it on the windowsill to charge the night before, but because he was still feeling so sleepy the next morning he’d forgotten to grab it and drop it into his rucksack. By the time he realized it wasn’t there, they were already halfway to Grandma’s place in the countryside and it was already too late to turn around and drive home. Now that poor little phone of his was just charging away on the windowsill, all on its lonesome.

All on its lonesome, just like him.

Feeling a little unsure of himself, Oskar started exploring the garden. It was early June and the flowers were in full bloom. The whole place was perfectly nice, and Oskar actually enjoyed wandering around – that is, when he and his parents went to visit Grandma together. Sooner or later, the adults would move on to boring topics at the dinner table, eating and eating and having at least five cups of tea to wash it all down. At some point, Oskar just couldn’t take it anymore and would run outside. There, from a respectful distance, he’d inspect the bees buzzing in the blossoms, search for snails in the grass, and flip over the brick that always had worms hiding underneath. If he was lucky, he might spot a lizard on the logpile, and once a big magpie had landed on a branch just a couple of yards away. At these times, Grandma’s garden seemed like an extraordinary place, but it was just like any other kind of entertainment – once the fun was over, it was nice to go back home again. Nobody would want to stay at the cinema for two whole months, would they?

Oskar found his way to the brick and flipped it over. The earthworm was there as usual, as was a black beetle that scuttled off into the grass. He put the brick back the way it was.

Am I really going to come and see this worm every day now? he wondered in despair. I’ll wake up in the morning, walk outside, flip over the brick, and stare at the worm. But then what? What am I going to do with the rest of the day?

Oskar got up, walked to the middle of the garden and stood there. All around, he could hear the chirping of birds and the soft hum of insects. He could see his grandma bent over at the far edge of the vegetable patch. White clouds were frozen motionless in the sky. A lump formed in his throat. He felt terribly alone. The whole world around him felt strange and he didn’t know what to do about it.

I might as well go inside, he decided. I’ll curl up in a corner or crawl under the bed and just hide there.

Oskar recalled their visit to Grandma’s house last Christmas. Mum and Dad were sitting and talking with Grandma next to the Christmas tree, as always, while Oskar crept away to get a satsuma. Suddenly he spotted a mouse. Oskar froze, not daring even to breathe. The mouse didn’t notice him, though – it pattered round the floor a little then stopped where it was. It was so tiny and the kitchen seemed gigantic around it. The mouse twitched its whiskers, its black button-eyes glittering in the light.

Then it turned tail and scampered beneath a cupboard.

Oskar felt like doing the same thing right now – hiding or crawling off into a den. Just like the mouse in the kitchen, the garden was too big and too unfamiliar for him to handle all on his own right now.

So he went inside. All three of them had been sitting together in the kitchen just a few minutes ago. Oskar could still catch the trace of his father’s scent, and the seat cushion where he’d been sitting was a little wrinkled, reminding him that someone had just stood up from there. There was a bowl on the table filled with the sort of sweets that Oskar absolutely detested – ones they never bought in the city – ones which made his grandma’s whole house seem far less inviting. These sweets seemed to signal the fact that he’d been dropped off somewhere far from home, in a strange land where people practised strange customs and ate strange foods. Even the plates, cups, and sugar bowl felt unfamiliar. It was odd – this hadn’t bothered him when he’d visited with his parents. On the contrary, it had made him curious to inspect all Grandma’s things and compare them with what they had at home. On those occasions, it’d been exciting to drink from a completely different cup from the one he normally used. But now, it was suddenly unpleasant. All these unfamiliar things seemed almost to be glaring at him, demanding: ‘Who do you think you are? And what are you doing here?’

Oskar went into the living room. Altogether, not counting the kitchen, there were three rooms in his grandma’s house: the living room, Grandma’s bedroom, and Dad’s old room where Oskar now slept. Whenever they’d spent the night, he usually stayed on a campbed next to his parents. There was no need for the campbed now, of course – the entire bed and the room were all his. So that’s just where Oskar went now – the most familiar room in the house to him. But today it still felt somehow different and strange. The only truly familiar thing there was Oskar’s rucksack, which Mum had packed with his clothes before she left for America, and into which Oskar had forgotten to pack his phone.

A mouse could wriggle into its nest and immediately feel at home there, because it was stocked with all sorts of cosy stuff. Oskar, on the other hand, was having a very hard time feeling at home in Dad’s old bedroom. It was filled with all the wrong things, the wrong smells, the wrong colours. Sunlight was streaming in through the window, but the whole space somehow felt cold. The big white crocheted blanket laid over the bed glinted coldly and the pillows looked too puffy.

Oskar walked over to the bookshelf. He knew how to read but there were only grown-up books on the shelves. Dad had taken all his own old children’s books back to the city for Oskar to read a long time ago. Oskar’s mood grew even gloomier. There wasn’t even anything to read! What on earth was he going do for two whole months? Sit and stare out the window for hours on end, just like the Ghost Lady?

The Ghost Lady lived in the house over the road from them in the city. Oskar didn’t actually know her real name – Ghost Lady was just what he called her. Day after day, this woman would sit in her apartment and stare out of the window. It usually only took Oskar a single glance outside to spot Ghost Lady up on the third storey of her building. She was ancient, with snow-white skin and long grey hair. Oskar used to be afraid of her when he was little, which was how he came up with her nickname. He’d got used to her presence over time, but the name had stuck.

Before, Oskar couldn’t wrap his mind around how someone could bear to stare out of a window for days and days, as if she were a potted plant on the windowsill. He was always busy as a bee running around town, and rarely stared out the window, if ever – only sometimes before going outside to check if it was raining or not. Or when he heard a siren wailing and wanted to see a fire engine or police car speeding by. Ghost Lady, on the other hand, would already be sitting at her window when Oskar woke up in the morning and would still be passing the time there when he went to bed at night. It had seemed bizarre to him before, but now he reckoned maybe Ghost Lady just felt lonely, too. Maybe she had been taken away from home, dropped off in the city with her kids, and now she didn’t know what to do with herself in such a strange place, either. Just the way Oskar was feeling now.

He went to the window and stared outside. A few yards away was Grandma’s shed. Next to the shed stood a lone birch tree so tall that Oskar had to crane his neck back to glimpse its crown. There was nothing else interesting in sight, so Oskar sat there gazing at the shed and the birch tree for a long time as if they were great wonders of the world. There was nothing else better to do, anyway.

The cuckoo clock in the living room chimed and the cuckoo popped out three times. An hour had passed since Dad left! Just one hour! Oskar thought about trying to figure how many hours there are in two months, but the maths was too hard for him to work out. He could already tell that the number would be frightfully large, anyway. It was better not to know.

‘Still, I won’t turn into a Ghost Lady,’ he decided. ‘I might as well go outside and walk ten circles around the house. Or twenty, even. Then maybe it’ll be night-time and I can go to bed. And then day one will be over.’

3.

Alas, it was not as easy as that. Oskar walked his twenty circles, but it was still a long time until evening – the sun was high in the sky. Grandma emerged from the vegetable garden, flashed Oskar a look of approval, and said:

‘Keep up the pace, lad! It’s nice to take a walk in the countryside. It’s nice being in the countryside in general – you can be out in the fresh air whenever you like. You can run and jump to your heart’s content and nobody’s going to stop you.’

She disappeared inside for a moment, came out carrying a gigantic pair of hedge clippers, and then went off somewhere else again.

Oskar considered running and jumping around like his grandma had suggested, but that seemed silly. Instead, he discovered a spider that had spun a web between a flowerpot and the corner of the house. He kept an eye on it for a long time, hoping a fly might get caught in the spiderweb so he could watch the way it ate – something he bet would be both horrifying and exciting at the same time. However, not one fly buzzed past. The spider sat there, motionless, and Oskar soon grew tired of watching.

He walked down to the gate and stuck his nose between the slats. Behind the gate wound a gravel road, and on the other side of that was a thicket. Oskar knew the road led to the village shop, where he’d once gone with his grandma. He wondered if going to the shop might offer any sort of entertainment. Maybe they sold decent sweets there? What if he asked Grandma to go with him?

But before Oskar could make his decision, he spotted the village kids.

There were three of them, all boys about Oskar’s age. They were oddly similar: each had hair that was white as cotton, and broad button-noses. The boys were apparently brothers, the younger two probably twins. As soon as they noticed Oskar, they came to a halt. Both sides stared at each another – Oskar from the garden, the boys from behind the fence.

Oskar felt an ice-cold ball form in the pit of his stomach, just like he always did whenever he ran into anything menacing. Any second now they might invite him to come play, and then he’d have to go – there’d be no way out of it. There was no point in running back to his grandma, and his parents were far away – no one was there to help him. Why on earth had he shuffled over to the fence, where he was such easy prey for anyone walking past? He should have just stayed inside, staring out the window like the Ghost Lady!

‘Who’re you?’ the oldest boy asked.

Oskar didn’t answer; he just stared at his shoes. He didn’t want to be rude, but how could he answer a question like that? If the boy had asked him his name, then he could’ve said ‘Oskar’. But what when someone asks ‘Who are you?’ do you say you’re a person? Or a boy? They could tell that already.

‘Is Burnmire your grandma?’ the taller cotton-haired boy asked again.

Oskar knew perfectly well that his grandma’s surname was Burnmire, just like his own last name, but it seemed so weird to hear a stranger refer to her that way. It was as if he wasn’t a kid, but a tiny grown-up! Still, the second question was easier to understand, so he nodded.

‘You want to play football?’ the boy asked.

The cold feeling in Oskar’s belly shot straight up to his throat and made it ache. It was happening! They were going to drag him off somewhere past the woods and he’d never find his way back to his grandma’s house again! He’d be forced to spend the whole afternoon with these total strangers, even though he didn’t want to at all. Who knows – maybe they wouldn’t even let him go home at night, but would make him a tantalizing offer to sleep in their fort. What boy could turn down a cracking idea like that?! And since Oskar wouldn’t be able to find his own way home and the unfamiliar boys wouldn’t bother to show him either, he’d have no choice but to go along with them and sleep in that fort. And the next morning, they’d take him fishing and then come up with a plan to go hiking and sailing and who-knows-where-else and he’d never make it back to his grandma’s or ever see his parents again!

‘You want to play football?’ the village boy repeated.

Suddenly Oskar remembered there was a fence and a gate dividing them! What would happen if he shook his head? If he declared, ‘No!’ in a loud, clear voice? But for some reason, everyone – even his mum and dad – thought it had to be the greatest thing in the world when one boy asked another to play, and no one could refuse such an invitation. It would’ve been impossible to refuse the offer if any adults were around. They’d have interfered right away, saying: ‘What do you mean, you don’t want to? Go ahead! These kids are inviting you! It’s fun to kick a ball around! Go, go on, Oskar!’ But right now he was alone and no one could force him to do anything. Oskar shook his head and said:

‘No, I can’t... Not today.’

The cotton-haired boys eyed him curiously for a moment.

‘Oo-kay,’ the oldest one drawled, and they continued on their way without looking back. Oskar had gotten away with it!

Only this once, though. Oskar couldn’t curse himself enough for his mistake, Why had he added ‘not today’ when he turned them down?! He was just being polite, of course, and just wanted to soften his tone. There was no need for that; none at all! Now the boys might think he’d be up for joining them tomorrow or some other day. It was possible they’d be back at the gate first thing next morning to make their offer again. Maybe they’d even come right up to the door and ask his grandma: ‘Mrs Burnmire, can your grandson come and play football with us?’ And Grandma would naturally reply: ‘Of course he can! What’s a kid to do in the countryside if not run around kicking a ball all day long?!’ Then there’d be no way out of it.

Oskar felt downright angry at these cotton-haired yokels. What did they want from him? He would never dream of inviting an unfamiliar kid to play! Grown-ups don’t just become friends at first sight now, do they! It’d be weird if some stranger walked up to Dad and told him, ‘Let’s go,’ and Dad simply trotted off after him. But with kids, those things are taken as a given – as if simply being more or less the same age as someone is reason enough for friendship.

‘I could tell them I’m sick,’ Oskar thought, remembering how his throat had just started aching from anxiety. It was still a little sore now, so the excuse wouldn’t be a complete lie.

He walked back to the house, sat down on the doorstep, and rested his chin on his knees. Grandma walked up and smiled:

‘Tired already? I suppose fresh air does wear you out if you’re not used to it. Come on in, we’ll have dinner. Afterwards we can play a board game. Life – have you heard of it? It’s your father’s; he played it all the time when he was little. Come in, come in.’

Oskar obediently followed her inside. They drank tea and ate sandwiches. The tea had a strange, unfamiliar taste. Grandma explained it was wild thyme tea, which people always drank in the countryside. The sandwiches were unbelievably thick because Grandma sliced the bread herself. Back in the city, bread was always nicely pre-cut at just the right thickness and packed in a bag. Grandma added sliced sausage to the sandwiches, but since the bread was so thick already Oskar could barely taste the meat. It was as if his whole mouth was packed with plain bread, which was so doughy and chewy that it just rolled around this way and that, proving almost impossible to swallow.

Afterward, they played Life, which was appallingly boring. There were some exciting possible turns to the game, but neither Oskar nor Grandma were so lucky. All they could do was plod on dully to the finish. On top of that, Oskar caught his Grandma cheating: whenever she rolled a six, she would cover it with her hand and say she’d rolled a three or a four, all so that Oskar would definitely win. Oskar didn’t confess that he saw straight through her trick, and just went along with her unselfish plan. Still, that made the game even less interesting.

‘Would you look at that? You won!’ Grandma cheered. ‘Good boy! Wasn’t that a fun game? Your father used to play it all the time.’

Oskar couldn’t believe his dad could have done anything this dull as a child, but he didn’t say anything. They turned on a kid’s TV programme, but Grandma soon dozed off and even started snoring after a while. Oskar couldn’t hear what the characters were saying anymore, but the programme wasn’t very interesting anyway. He slid off his chair and walked to the window. Outside, a thick grey fog was creeping through the garden, covering all the flowers and bushes. It was pretty in a way, but at the same time it made him a little sad, too. Oskar felt like he was cut off from the whole world like a lone shipwrecked sailor on an uninhabited island. All that existed were his grandma’s house and the ground close by; everything else was blanketed in an impenetrable veil. Beyond it – somewhere far, far away – was Oskar’s home and his dad, and even farther away was mysterious, enticing America and his mum. Beyond that veil were all the other fantastic places he knew. Alas, he couldn’t see any of them – they’d all been swallowed up by the fog.

The TV remote slipped from Grandma’s hand, banged against the floor and she woke up.

‘What do you know, I dozed off there for a minute,’ she sighed. ‘Come now, Oskar. Let’s brush your teeth. It’s time for bed.’

4.

By morning, the fog had disappeared and the sun was shining. Oskar was now used to the bed which had seemed so dubious just yesterday, and he no longer wanted to get up. It was nice and warm beneath the sheets. Overnight, it had become that mouse’s nest he’d been looking for – a place to crawl into and curl up.

Grandma was clattering about in the kitchen. She crossed the living room with heavy footsteps and peeked into Oskar’s bedroom.

‘Come and eat, Oskar!’ she called out. ‘It’s such a beautiful morning – it would be a shame to sleep through it.’

Oskar couldn’t care less about the beautiful morning, but he climbed out of bed anyway. ‘At least I’ve managed to tame one thing,’ he thought, eyeing his rumpled bedsheets in satisfaction. He imagined himself as a caveman living in a dangerous jungle filled with all kinds of wild animals. They growled and yelped between the trees with flashing eyes and bared teeth. But then the caveman managed to win over one beast, then another... And in the end each of them came up to lick their master’s hand. The frightful predators had all become pets. ‘Maybe I should do something like that with Grandma’s house,’ Oskar thought. ‘I’ve already tamed my bed, pillows and blankets – maybe I can get the better of the rest of the house, too!’

He went into the kitchen to eat breakfast and immediately realised that taming a jungle is no easy task. His spoon was slightly too big and the porridge slightly too thick. How would he ever get used to that? The jam was certainly tasty, though, and Oskar could’ve simply spooned it straight from jar to mouth, but he doubted that would be acceptable here. At home, he’d definitely have abandoned the thick porridge and just emptied the jar of jam instead, but he was a bit hesitant to act like that at Grandma’s house.

‘Dig in!’ Grandma encouraged him. ‘This was your grandpa’s favourite porridge.’

That news didn’t make the meal any tastier. Grandpa had passed away a long time ago – Oskar never even got to meet him. He was like a total stranger, and if he really had loved that thick porridge then it made the meal all the more bizarre. It wasn’t the first time Oskar had noticed that old people preferred weird foods, and if porridge like that had been the favourite breakfast of some long-ago grandfather then there was no way he, Oskar, could like it. Kids eat different things from old people – restaurants even have separate kids’ menus!

‘Grandpa would have his porridge with butter instead of jam, and he’d sprinkle a little salt on top too,’ continued Grandma, with her back to Oskar as she did the ironing. ‘And if there was some herring on the table, then he’d toss that into the bowl as well. That’s how he ate, your grandpa.’

Oskar completely lost his appetite. The porridge now seemed downright disgusting – it gleamed weirdly like it was doused in melted butter instead of jam. Oskar could even imagine the silvery head of a dead fish sticking out of the sludge, gaping at him. Ugh! He couldn’t stomach another mouthful.

‘Thanks, I’m full,’ he said softly. Grandma turned around and blinked in surprise at the nearly untouched bowl.

‘Didn’t you like it?’ she asked.

‘I did, but...’ Oskar trailed off. ‘I’d like to go outside now.’

Grandma approved at once of this idea.

‘Of course, go right ahead!’ she said. ‘Kids should be outside here, in the country. You’ll have more than enough time for sitting around indoors in the city next winter!’

Oskar ran out the door. It was a genuine relief to get away from that appalling breakfast! He stopped in front of the house, basking in the bright sunshine. Still, he hadn’t worked out what to do next.

It wasn’t bad just standing there at first – the sun was nice and warm. A woodpecker tapped on an apple tree; Oskar approached it curiously, but the bird fluttered away into the woods. He gripped his hands behind his back and began to head for the gate, but then turned on his heels and made his way back to the house. Those cotton-haired boys might be lurking just beyond the gate and lure him into joining them if they spotted him! Just in case, Oskar circled around to the back of the house.

The door to Grandma’s shed was ajar, so Oskar slipped inside. Its tiny windows didn’t let in much light, making the place rather dim, but he could still make out all the objects stored there.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)