Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

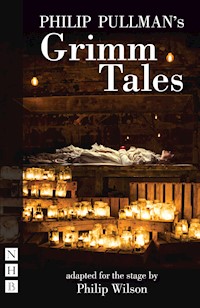

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

What is that, trailing your footsteps, breathing softly down your neck? Rediscover the magic and wonder of the original Grimm Tales, retold by master-storyteller Philip Pullman. In this stage version by Philip Wilson, you'll meet the familiar characters – Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel – and some unexpected ones too, such as Hans-My-Hedgehog, the Goose Girl at the Spring and the remarkable Thousandfurs. Full of deliciously dark twists and turns, the tales come to life in all their glittering, macabre brilliance – a delight for children and adults alike. These Grimm Tales, adapted for the stage by Philip Wilson from Philip Pullman's version of the original tales, were first performed as immersive storytelling experiences underneath Shoreditch Town Hall, London, in 2014, and Bargehouse on the South Bank in 2015. They also offer plentiful opportunities for youth theatres, schools and amateur companies looking for a vivid new version of the classic fairytales.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 215

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Philip Pullman’s

GRIMM TALESfor Young and Old

adapted for the stage by

Philip Wilson

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Thanks

Foreword by Philip Pullman

Telling Tales by Philip Wilson

Original Production Credits

The First Set of Tales

Little Red Riding Hood

Rapunzel

The Three Snake Leaves

Hans-my-Hedgehog

The Juniper Tree

The Second Set of Tales

The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich

The Three Little Men in the Woods

Thousandfurs

The Goose Girl at the Spring

Hansel and Gretel

Faithful Johannes

The Donkey Cabbage

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

This volume contains dramatisations of twelve different Tales arranged in two complementary groups – enough material for two complete productions. Alternatively, companies can make their own selection as required, with the fees reflecting the number of Tales to be told.

With thanks to everyone who was involved with the two productions, at Shoreditch Town Hall and at Bargehouse.

This script is a testament to their imagination, invention, creativity – and hard work.

Foreword

Philip Pullman

When Penguin Classics asked me if I was interested in writing a fresh version of some of the tales of the Brothers Grimm, I had to suppress a whoop of delight. Actually, I’m not sure that I did suppress it. I’ve always relished folk tales, and the famous Grimm collection is one of the richest of all. It was a dream of a job.

Reading them through carefully and making notes, I was struck again by the freshness, the swiftness, the sheer strangeness of the best of them. I was being asked to choose fifty or so out of the more than two hundred, and there were certainly at least that many that deserved a new outing. The most interesting thing, perhaps, from a dramatic point of view, is that they consist entirely of events: there’s no character development, because the characters are not fully developed three-dimensional human beings so much as fixed, flat types like those of the commedia dell’arte, or like the little cardboard actors (a penny plain, tuppence-coloured) we find in the toy theatre. If we’re looking for psychological depth, we won’t find it in the fairy tale.

Nor is there anything in the way of poetic description or rich and musical language. Princesses are beautiful, forests are dark, witches are wicked, things are as red as blood or as white as snow: it’s all very perfunctory.

What we find instead of these literary qualities is a wonderful freedom and zest, entirely unencumbered by likelihood. The most marvellous or preposterous or hilarious or terrifying events happen with all the swiftness of dreams. They work splendidly for oral telling, and the very best of them have a quality that C.S. Lewis ascribed to myths: we remember them instantly after only one hearing, and we never forget them. The job of anyone telling them again is to do so as clearly as possible, and not let their own personality get in the way.

They can be told, of course, and they can be dramatised, in any of a thousand different ways. They have been many times, and they will be many more. This particular version was very enjoyable for me to read and to watch because Philip Wilson is so faithful to the clarity and the force of the events, just as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were faithful to the talents of the various storytellers whose words they listened to and transcribed two hundred years ago. And they still work.

Telling Tales

Philip Wilson

The Brothers Grimm’s stories have been retold countless times over the past two centuries. Katharine Mary Briggs, Italo Calvino and Marina Warner included versions in their classic collections of fairy tales, and writers such as Angela Carter, Terry Pratchett and Carol Ann Duffy have revelled in inventive variations. In recent years, two films of Snow White appeared, Maleficent re-imagined the story of Sleeping Beauty, Sondheim’s Into the Woods was filmed, and Terry Gilliam gave the lives of the brothers themselves a high-spirited storybook twist in The Brothers Grimm. Moreover, the latest anthropological research indicates that the origins of folk tales such as Little Red Riding Hood and Beauty and the Beast can be traced back millennia.

In 2012, Philip Pullman selected fifty of his favourite Grimm Tales to retell. His intention in doing this, he declared, was ‘to produce a version that was as clear as water’. In the same way, my dramatisations seek to retain the limpid and beautifully crafted character of the original stories. The telling of the Tales is shared between an ensemble of performers, who play husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, princes and princesses, wise kings and wicked witches, snakes and birds. The original productions, drawing on puppetry, movement and music, were a theatrical celebration of live storytelling. At Shoreditch Town Hall, we brought to life the adventures of Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel, The Three Snake Leaves, Hans-my-Hedgehog and The Juniper Tree. At Bargehouse, meanwhile, we retold the Tales of The Frog King, or Iron Heinrich, The Three Little Men in the Woods, Thousandfurs, The Goose Girl at the Spring, Hansel and Gretel and Faithful Johannes. Also included here is my adaptation of The Donkey Cabbage, a story we didn’t find a home for, but is too good to forgo.

This was a deliberately eclectic selection, which embraced a variety of classic story plots – quests and voyages, rags to riches and overcoming monsters – within the core genres of comedy, tragedy, romance… and, sometimes, surrealist farce! Their appeal lay also in how they have echoes of Shakespeare and Ancient Greek tragedy, incorporating as they do rites of passage, ghosts of fathers, animal transformations. And how they embody the themes of human life: births, marriages and deaths; sibling support (or rivalry); parental cruelty; the hardships of poverty; jealousy and desire.

While it is eminently possible to stage these stories in traditional theatre environments, ours was an immersive approach: the audience were divided into groups, and took different journeys through the various parts of the venue. After each Tale, this group was guided by the performers to another space. On their way, they glimpsed images evoking hints of other Tales untold, as they passed through rooms from which other characters seemed to have only just departed – leaving Cinderella’s pile of lentils by an iron stove; Snow White’s glass coffin, along with seven identical small beds; Rumpelstiltskin’s spinning wheel in a shaft of light, in a room with straw on one side and a cloud of gold objects on the other. And so on…

The world of the play was ‘scruffy salvage’: an elemental world of rough-hewn wood, tarnished metal, unrefined cloth. The costumes were tattered, puppets were constructed from found objects, and everyday items were often used in place of the thing described. All were transfomed by the Storytellers’ investment in them. Wooden scrubbing brushes were sewn onto a duffle coat for Hans-my-Hedgehog’s prickly skin; thick rope stood in for Rapunzel’s hair; an enamel coffee pot became a white duck. This approach both ensured that these dark Tales were not prettified, and gave a sense that the performers had drawn on what might lie around them, to supplement and enhance the storytelling. We invited the audience to complete the picture with their imagination.

There was no attempt either to set the stories in the age in which they were written down or to transpose them to a contemporary setting. Rather, they existed in a glorious miscellany of different styles, periods and cultures – anchored by the ‘scruffy salvage’ aesthetic – to echo the magpie-like origins of the Tales. Nor were we constrained to Europe. In The Three Snake Leaves, the number four is very important. In China, this is a symbol of unluckiness – which chimes with this Tale’s more Eastern feel: it doesn’t read like it’s from a Northern European tradition. Similarly, the Princess of the Golden Roof seemed to have travelled as far as she does with Faithful Johannes. These stories know no borders.

Interwoven with the action at Shoreditch was music, sung live, and drawn from Der Zupfgeigenhansl – a collection of German folk songs compiled by the Wandervögel or ‘wandering bird’ movement, which celebrated journeys of discovery. At Bargehouse, there was also a quartet of actor-musicians in glorious felt headdresses of a donkey, a dog, a cat and a cockerel, echoing another group of Grimm characters, the Musicians of Bremen.

After the performance, further spaces were revealed for the audience to explore, filled with hanging ballgowns; rooms filled with curious items; walls of bizarre and macabre images…

But that is just one approach. There are as many ways to tell a story as there are stories themselves. You only have to look at how the Tales have been illustrated: a brief internet search will reveal endless depictions in different styles, to offer inspiration. A very brief list might include: Elenore Abbott, Angela Barrett, Edward Burne-Jones, Katharine Cameron, Walter Crane, George Cruikshank, Gustave Doré, Edmund Dulac, David Hockney, Franz Jüttner, Margaret Pocock, Evans Price, Arthur Rackham… In recent years, fairy tales have also been drawn upon by a range of artists, from Paula Rego to the fashion photographer Tim Walker.

If you wish to delve more into the psychology of this world, the Queen, as it were, of fairy tales is Marina Warner: and you will find her work – including Once Upon a Time and From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers – overflowing with ideas. Other books we referred to included Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Katharine Mary Briggs’ three-volume Folk-Tales of Britain and Sheldon Cashdan’s The Witch Must Die: The Hidden Meaning of Fairy Tales.

Although the stories are uncluttered in language and spare in detail, nonetheless they resonate with all manner of human experience. Philip Pullman is right that on the page, the characters appear flat: these are archetypes, defined by their class, profession or role in society. In fairy tales, people are what they do. This does not mean, though, that there is no room for dramatic characterisation. The stories certainly include tension and conflict. And they deal with universal situations, in which the drama often springs from family ties: the characters could be us. So we can add our detail or psychology, through expression, gesture, nuance… all of which springs from the engine of fairy tales, which is desire.

In the modern world, the depiction of women in fairy tales is controversial. Admittedly, there are archetypal ‘evil’ female characters, many of whom, as Marina Warner comments, ‘occupy the heart of the home’ – the wicked mother, the queen, and the fabled stepmother. These are often the agents of potent and lethal spells. Plus, there are also women as images of perfection, such as the Princess of the Golden Roof in Faithful Johannes – a goddess on earth. And there is a fair bit of crying…

However, the female characters are also supremely resourceful. In The Juniper Tree, Marleenken buries her brother’s bones – and thereby starts the process of retribution on their evil stepmother. It’s Gretel that kills the witch, releases Hansel and suggests they cross the lake on the duck’s back one by one. Thousandfurs is also extremely resilient – both in creating obstacles against her incestuously lustful father, and then in ensuring that she stays safe. And although The Man’s Daughter in The Three Little Men in the Woods is resolutely kind and unshakeably generous, she also won’t stay dead! And returns (spoiler alert) to ensure that her stepmother and stepsister get their comeuppance.

In German, fairy tales are known as wonder tales. This term encourages us to celebrate these fantastic characters and episodes in all their eccentric glory, from the picturesque to the grotesque, and from the magical to the mundane – free, above all, from the sanitisation and lavish naturalism of later versions, not least Disney films.

Fairy tales exist in a world of enchanted forests and stone castles, soaring towers and bottomless seas. Plus, the action moves lightly and speedily from location to location. So it is key not to get bogged down in place. While there is a need to create a setting, an environment, an arena for storytelling, remember the appeal made by the Chorus in Shakespeare’s Henry V, ‘Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them.’

That word, talk, reminds us that although the Tales were written down, shaped and curated by the Brothers Grimm, these stories emerged from oral traditions: they have always been intended to be spoken aloud. There is an innate human desire to gather together and listen to a storyteller, or to witness a group reenacting a tale. My approach has been to divide up the voices among a group of Storytellers. Each Tale starts with some variation on ‘Once…’ (the universally agreed way of starting a story), followed by a brief introduction to the key figures and situation – along with their voices. Thereafter, the words are shared in three modes of speech: dialogue, narration and ‘thinking aloud’. Viewpoint and attitude is crucial throughout. Also, you’ll note how characters move from retelling to reliving events: the intention is always to ensure that the story is immediate, is happening right now – not comfortably in the past.

This immediacy is particularly important in the second mode of speech, narration. Often, characters comment on the action; even before they have been fully introduced into the story. For instance, in The Frog King, The King observes and comments on The Princess, while Faithful Heinrich – the character least familiar to us in this Tale – does the same for his master, until at last he is able to tell his story. Sometimes, the characters cannot be aware of what is going on at a particular moment, but as Storytellers, they know all, and help to advance the Tale. This occurs especially at moments of secrecy, magic or ritual: such as when the Servants describe Thousandfurs’ transformation for the balls, or when The King and The Queen observe The Goose Girl’s washing ritual. While they do not have a role as such at this point, their connection to the story is no less opinionated, active, defined. And since they won’t be able to change costume, the distinction must be made through vocal tone, within the guise of their main character.

Throughout the Tales, whether on the edge of the action or in the middle of it, no Storyteller is apart from it. And each one must be mindful always of their audience. Hamlet says, ‘We’ll hear a play tomorrow’ – and however vivid and sensuous a production you create, at its heart should always be the words, and a delight in language.

The punctuation of Philip Pullman’s text has been retained, so that it is clear where a phrase relates to the one before, and also which parts are dialogue, which narration, and which thinking aloud: in order to suggest the rhythm and patterns of sharing these speeches. He compares storytelling to jazz, observing that, ‘the substance of the tale is there already, just as the sequence of chords in a song is there ready for a jazz musician, and our task is to step from chord to chord, from event to event, with all the lightness and swing we can.’ That sense of working in tandem with other players, while retaining an improvisatory quality, is key to staging these Tales. It’s all about the ensemble.

When creating a company, consider carefully the doubling between the Tales. Giving each perfomer a variety of roles – a witch in one, a kind woman in another; a wise man at first, a foolish one later – not only gives actors a fruitful challenge: it also heightens the sense that it is not always clear how people really are when you first meet them. Even within stories, there is much scope for doubling and transformation (what was done in the original productions is indicated at the start of each set of Tales). And bear in mind the power of the numbers three and seven: trios, in particular, are the staple of fairy tales.

Although any number of these Tales can be told, and in any order, in the original productions more familiar stories were performed first, before the audience was led into darker, less-well-known territories: deeper into the forest.

Much of the action is indicated within the storytelling: rather than demonstrate this, the staging should elucidate what is described. The language is spare: there is, deliberately, little there – which allows for nimble movement, a deft negotiation of the sudden shifts in situation. Stage directions have been kept to a minimum: generally, the text is its own prompt book. Most importantly, these Tales live most when they are imbued with the imaginations of those who are telling them: so it is not only right but crucial that you find your own path through the text.

Whichever route you take, what’s important is what happens next. Philip Pullman has observed that, ‘Swiftness is a great virtue in the fairy tale. A good tale moves with a dreamlike speed from event to event, pausing only to say as much as is needed and no more.’

My intention has been to tell these Tales with a similar economy, clarity and passion.

The first performance of the First Set of Tales took place at Shoreditch Town Hall, London, on 14 March 2014.

THE STORYTELLERS

Ashley Alymann

Sabina Arthur

Rebecca Bainbridge

Annabel Betts

James Byng

Paul Clerkin

Lindsay Dukes

Simon Wegrzyn

THE STORYMAKERS

Director

Philip Wilson

Set and Costume Designer

Tom Rogers

Lighting Designer

Howard Hudson

Composer and Sound Designer

Richard Hammarton

Assistant Director

Sarah Butcher

Casting Director

Kay Magson CDG

Costume Supervisor

Alexandra Kharibian

Puppet Maker

Sinéad Sexton

Design Assistants

Anna Jones

Nancy Nicholson

Nefelie Sidiropoulou

Producer

Valerie Coward

Executive Producer

Cat Botibol

Production Managers

Timothy Peacock

and Stage Managers

Cecily Rabey

Stage Manager

Chris Tuffin

Assistant Stage Manager

Sinéad Sexton

Wardrobe Mistress

Nicole Graham

Electrician

Adam Mottley

Sound Technician

Mark Cunningham

Production Photographer

Tom Medwell

Rehearsal Photographer

Matt Hass

Special thanks to Nick Giles and all the team at Shoreditch Town Hall.

The first performance of the Second Set of Tales took place at Bargehouse, Oxo Tower Wharf, South Bank, London on 21 November 2014.

THE STORYTELLERS

Kate Adler

Sabina Arthur

James Byng

Paul Clerkin

Morag Cross

Amanda Gordon

Leda Hodgson

Richard Mark

Nessa Matthews

Anthony Ofoegbu

Maria Omakinwa

Joel Robinson

Megan Salter

John Seaward

Johnson Willis

Robert Willoughby

THE STORYMAKERS

Director

Philip Wilson

Set and Costume Designer

Tom Rogers

Lighting Designer

Howard Hudson

Composer and Sound Designer

Richard Hammarton

Assistant Director

Sarah Butcher

Magic Consultant

Darren Lang

Casting Director

Kay Magson CDG

Costume Supervisor

Jennie Falconer

Puppet Designer and Maker

Alison Duddle

Animal Headdress Maker

Barbara Keal

Design Assistants

Robson Barreto

Simon Bejer

Mika Handley

Nefelie Sidiropoulou

Instrument Design

Flora Pickering

Producer

Valerie Coward

Executive Producer

Cat Botibol

Production Manager

Andy Reader

Stage Manager and Assistant Production Manager

Timothy Peacock

Technical Stage Manager

William Cottrell

Deputy Stage Manager

Ellen Dawson

Assistant Stage Managers

Kirsty MacDiarmid

Sinéad Sexton

Alice Barber

Wardrobe Mistresses

Lydia Cawson

Nicole Graham

Master Carpenter

Dario Fusco

Carpenters

Stuart Farnell

Ben Lee

Rob Pearce

Ben Porter

Bob Weatherhead

Set Build Assistants

Henry Culpepper

Natalie Favaloro

Sasha Mani

Scenic Coordinator

Georgina Foster

Scenic Art

Ashleigh Blair

Bethe Crews

Charlotte Lane

Chief Electrician

Laurence Russell

Deputy Chief Electrician

Jordan Lightfoot

Lighting Technicians

Sarah Harrison

Scott Hislop

Ben Redding

Production Sound

Mike Walker

Chris Simpson

Ryan Griffin for Loh-Humm Audio

Front of House Manager

Chris Burkitt

Design Director

Gareth Paul Jones

Copywriter

Josephine Ring

Web Development

Merlin Mason

Assistant to Producers

Nadia Aminzadeh

Production Photographer

Matt Hass

Rehearsal Photographer

Tom Medwell

Special thanks to all the team at Bargehouse.

‘All we need is the word “Once…” and we’re off’

Philip Pullman

THE FIRST SET OF TALES

Little Red Riding Hood

Rapunzel

The Three Snake Leaves

Hans-my-Hedgehog

The Juniper Tree

The Storytellers

Little Red Riding Hood

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD

THE MOTHER

THE WOLF

THE GRANDMOTHER

THE HUNTSMAN

This Tale can be told by a cast of four:

Little Red Riding Hood

The Mother / The Grandmother

The Wolf

The Huntsman

Rapunzel

THE WIFE

THE HUSBAND

THE WITCH

RAPUNZEL

THE PRINCE

RAPUNZEL’S SON

RAPUNZEL’S DAUGHTER

This Tale can be told by a cast of four:

The Wife / Rapunzel

The Husband / Rapunzel’s Son (puppet)

The Witch / Rapunzel’s Daughter (puppet)

The Prince

The Three Snake Leaves

THE POOR MAN

THE SON, later THE SOLDIER

THE KING

THE SECOND SOLDIER

THE THIRD SOLDIER

THE PRINCESS

A SENTRY

THE SOLDIER’S SERVANT

THE CAPTAIN

This Tale can be told by a cast of four:

The Poor Man / The Third Soldier / A Sentry / The Soldier’s Servant

The Son, later The Soldier

The King / The Captain

The Princess / The Second Soldier

Hans-my-Hedgehog

HANS-MY-HEDGEHOG

THE FARMER

THE WIFE

THE MAIDSERVANT

THE FIRST FARMER

THE SECOND FARMER

THE PRIEST

THE FIRST KING

THE SERVANT

A COURTIER

THE FIRST PRINCESS

THE SECOND KING

THE MESSENGER

THE SECOND PRINCESS

A FARMER

ANOTHER FARMER

A THIRD FARMER

THE PHYSICIAN

This Tale can be told by a cast of four:

The Farmer / The Servant / The Second King / A Third Farmer

The Wife / A Courtier / The Messenger / The First Princess A Farmer / The Physician

The First Farmer / The Maidservant / The First King / The Second Princess / Another Farmer

The Second Farmer / The Priest / Hans-my-Hedgehog

The Juniper Tree

THE FIRST WIFE

THE SECOND WIFE

THE SON, later THE BEAUTIFUL BIRD

THE RICH MAN

THE DEVIL

MARLEENKEN

A GOLDSMITH

THE GOLDSMITH’S FIRST APPRENTICE

THE GOLDSMITH’S SECOND APPRENTICE

A SHOEMAKER

THE SHOEMAKER’S WIFE

THE MAID

THE MILLER’S FIRST APPRENTICE

THE MILLER’S SECOND APPRENTICE

THE MILLER’S THIRD APPRENTICE

This Tale can be told by a cast of four:

The First Wife / Marleenken (puppet) / The Goldsmith’s Second Apprentice / The Maid / The Miller’s First Apprentice

The Second Wife / The Shoemaker’s Wife / The Goldsmith’s First Apprentice / The Miller’s Second Apprentice

The Son, later The Beautiful Bird (puppet)

The Rich Man / The Devil / A Goldsmith / A Shoemaker / The Miller’s Third Apprentice

Little Red Riding Hood

For this Tale, it is important to distinguish between the two houses – one in which THE MOTHER and LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD live; the other where THE GRANDMOTHER resides – and the perilous path that lies between them, through the woods. It would be useful to have some way of THE GRANDMOTHER – and later LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD – being able to disappear into the bed, ready to emerge later.

THE MOTHER. Once upon a time

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. there was a little girl

THE HUNTSMAN. who was so sweet and kind

THE WOLF. that everyone loved her.

THE GRANDMOTHER. Her grandmother, who loved her more than anyone, gave her a little cap made of red velvet,

And she does.

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. which suited her so well that she wanted to wear it all the time.

So she slips this on.

THE WOLF. Because of that everyone took to calling her

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. Little Red Riding Hood.

THE HUNTSMAN. One day her mother said to her:

THE MOTHER. ‘Little Red Riding Hood, I’ve got a job for you. Your grandmother isn’t very well, and I want you to take her this cake and a bottle of wine. They’ll make her feel a lot better. You be polite when you go into her house, and give her a kiss from me. Be careful on the way there, and don’t step off the path or you might trip over and break the bottle and drop the cake, and then there’d be nothing for her. When you go into her parlour don’t forget to say, “Good morning, Granny,” and don’t go peering in all the corners.’

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. ‘I’ll do everything right, don’t worry,’

THE HUNTSMAN. said Little Red Riding Hood,

THE MOTHER. and kissed her mother goodbye.

Basket in hand, LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD sets off on her journey.

THE HUNTSMAN. Her grandmother lived in the woods, about half an hour’s walk away.

THE WOLF. When Little Red Riding Hood had only been walking a few minutes, a wolf came up to her.

THE MOTHER. She didn’t know what a wicked animal he was, so she wasn’t afraid of him.

THE WOLF. ‘Good morning, Little Red Riding Hood!’

THE HUNTSMAN. said the wolf.

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. ‘Thank you, wolf, and good morning to you.’

THE WOLF. ‘Where are you going so early this morning?’

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. ‘To Granny’s house.’

THE WOLF. ‘And what’s in that basket of yours?’

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD. ‘Granny’s not very well, so I’m taking her some cake and some wine. We baked the cake yesterday, and it’s full of good things like flour and eggs, and it’ll be good for her and make her feel better.’

THE WOLF. ‘Where does your granny live, Little Red Riding Hood?’