9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

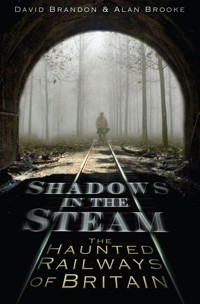

Ghosts traditionally make their presence felt in many ways, from unexplained footfalls and chills to odours and apparitions. This fascinating volume takes a look at some of the strange and unexplained hauntings across Britain's railway network: signals and messages sent from empty boxes; trains that went into tunnels and never left; ghostly passengers and spectral crew; the wires whizzing to signal the arrival of trains on lines that have been closed for years.... Based on hundreds of first-person and historical accounts, Shadows in the Steam is a unique collection of mysterious happenings, inexplicable events and spine-chilling tales, all related to the railways. Compiled by David Brandon and Alan Brooke, acknowledged experts on railways and the supernatural, and including sections on the London Underground and railway ghosts in literature and film, this book will delight lovers of railways and spooky stories alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Introduction: Ghosts and Spooky Spectres

List of Locations

1. The Stories

2. Ghosts of the London Underground

3. The Development of the London Underground

4. Haunted Underground Stations

5. Closed Railway Stations

6. Defunct Underground Stations

7. ‘Ghost’ Steam Trains

8. Road Signs to Ghost Stations

9. The Haunted Underground in Film and Television

10. Troglodytes!

11. The Haunted Underground and Literature

12. The Haunted Railway in Film and Literature

Glossary

Advertisement

Copyright

Introduction: Ghosts And Spooky Spectres

‘Millions of Spiritual Creatures walk the Earth Unseen, both when we wake and when we sleep.’

John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book IV

The ultimate mystery of life is what happens to us when we die. Is the vital spark, the soul that makes each of us unique individuals, simply snuffed out to be followed rapidly by the decay of our physical parts? Most of us are uncomfortable with the idea that the world with which we are so familiar continues after we die and, in particular, that it will cope perfectly well without us. How much better to hope or believe that there is indeed an afterlife? Such a possibility is, however, viewed by most of us with a mixture of awe, trepidation and downright fear.

Many of the world’s religions are preoccupied with the question of the continued existence of our souls after physical death. Indeed some religions teach that the earthly life is merely a preparation for the next, and that, when we die, we will have to account to the Deity for what we have done with our lives. Such religions have created elaborate codes of rights and wrongs which we ignore literally at our peril.

Most religions have created destinations for the souls of the departed. In the case of Christianity this is Heaven, the place where the righteous and good go and enjoy an idyllic existence for ever-after, and Hell, a state of perpetual nastiness for those who have devoted themselves to a life of sin. Some Christians believe in a third destination known as Purgatory. This is where souls undertake a process of being tried and tested until a decision is reached as to whether they should be elevated to Heaven or consigned to Hell.

If it is believed that human souls live on after the death of their material parts, it is only a small step to visualise the dead returning to the world of the living under certain circumstances. In many cultures it is thought that the dead yearn to return to the scene of their earthly lives and that they bitterly resent and envy those who they left behind who are still alive. The soul therefore returns, often angry and seeking revenge on someone who it perhaps believed wronged it while it was still alive. If, for example, its life was ended by murder, perhaps it wants to settle the hash of the murderer. There may be all sorts of other reasons why it wants to make its feelings known to the still-living.

On occasions the soul is apparently a trifle confused, but it appears to want to sort out some things that were left unresolved or otherwise unsatisfactory when its owner died. Perhaps it objects to the manner and place of its burial. Equally the soul may return if its physical remains are disturbed or treated with a lack of respect. It may return to provide someone living with a warning concerning their behaviour or perhaps to tell them of an impending disaster. A prime time for a ghostly reappearance in the land of the living is on the anniversary of a person’s death. Again, if any of this is to be believed, the ghost sometimes returns out of curiosity, simply to check on how affairs are being conducted in its absence. Some ghosts seem intent on returning to resume the habitual activities they undertook while still alive. Yet others act as if they want to seek atonement for the sins they committed while they were living. When it manifests itself on its return, the soul is said to be a ghost. Manifestations attributed to ghosts have both fascinated and frightened humans since the dawn of mankind.

There are many ways in which ghosts make themselves known. They may be seen or heard, although more often people claim that they have ‘sensed’ their activity or presence rather than anything more tangible. Perhaps they have smelt the stench of bodily corruption or experienced a sudden and literally chilling fall in the temperature around them. Unexplained footfalls; items removed or rearranged without apparent human agency; disembodied sighs, cries and groans; things that go bump in the night. Some people claim to have caught images of paranormal entities or activity on film, but the authenticity of such images is often disputed.

All these and a host of other unexplained phenomena feature in the continuous flow of reports made by people who claim to have had encounters with ghosts or other supernatural phenomena. Many of these people are not naturally suggestible, are not attention-seekers and may even be positively stolid and unimaginative. Some were frankly sceptical about anything to do with the paranormal before they had such an experience. In most circles a person talking about seeing ghosts is likely to invite ridicule. Being the butt of mockery makes most people feel uncomfortable. For this reason it is likely that many unexplained phenomena go unreported and therefore unpublicised.

Some of the following stories are of what might be called ‘serial hauntings’, where apparently the same ghostly activity is repeated in or around the same place. Other activities seem to be more of a one-off. Perhaps the ghost has completed the purpose for which it came back and, having no further business in the everyday world, returned whence it came. No one has ever been able to give a fully satisfactory explanation of why ghosts can apparently make their presence known to some people but not to others in the same place and at the same time. The ghosts may not even be the returning spirits of humans. Ghostly phenomena associated with cats, dogs and horses, for example, have also been reported.

Children’s fictional stories may have ghosts covered in white sheets, rattling chains and emitting screeching noises. In adult fiction the ghosts are generally more subdued or understated. In the works of that doyen of ghost story writers, M.R. James, the ghosts are little more than hints or suggestions. In spite of being so understated, they are capable of being extraordinarily menacing and malevolent. Truly the icy finger tracing out the spine.

Ghostly phenomena continue to exert a perennial interest even in a modern world dominated by the apparent rationalities of science and technology and a largely secular world deeply imbued with scepticism and cynicism. Each year priests carry out innumerable exorcisms in all seriousness intended to bring peace to the living and repose to the spirits of the dead.

Something atavistic, a vestigial sixth sense, can cause the hair to rise on the back of the neck at certain times and in certain places. Frissons of unease developing into fear may cause a rash of goose pimples for reasons we simply cannot explain. While we do not really like being spooked in real life, we love scary stories and most of us enjoy being comfortably scared. Ghosts are big business. Fictional ghost stories, ghost walks, films and documentaries about the paranormal have never been more popular. Spiritualism and psychic research are going strong and still trying to obtain the incontrovertible evidence that will sink the sceptics once and for all. Ghosts remain as much a part of popular culture as they were in the Middle Ages.

Do ghosts exist? If so, what are they? Do they have any objective existence or are they simply the product of superstitious minds, personal suggestibility or overheated imaginations? If we accept the claims of serious people that they have had experiences of a paranormal kind, what was it that they actually saw, heard or otherwise sensed? Isn’t there a commonsense or perfectly mundane explanation for most or all of these phenomena? Even if we do not wish to probe too deeply into these questions, most of us can still appreciate a spooky story or movie or can keenly anticipate jumping out of our skins at the appropriate moment on a ghost walk. They are part of the rich and fascinating tapestry of fact, folklore, myth and legend. There are even serious academic studies written on the subject, such as the very readable The Haunted: A SocialHistory of Ghosts, by Owen Davies, published in 2007.

One theory of haunting is that ghostly phenomena are a kind of spiritual film, a force generated in places where deeds of violence or great emotional upheavals have taken place. An energy is released which replicates at least some of the sights and sounds of these powerful events. This energy then allows the re-enactment of these events to be experienced from time to time by the still-living, or at least by those apparently receptive to paranormal or psychic phenomena. If there is any substance to this theory, it does account for the disappearance of some habitual or long-established haunting phenomena. The highly charged emotional ether simply dissipates over time.

If you ask people what kinds of places they expect to be haunted, they would probably include ‘Gothic’ semi-derelict mansions; the crypts used as charnel houses or bone-holes in some ancient churches; churchyards; hoary ivy-clad old ruins; dark and dingy castle dungeons; crossroads where gibbets used to display the mortal remains of executed highwaymen; and also the local ‘lover’s leap’, the scene of years of tragic suicides provoked by the miseries of unrequited love. To some extent such scenes are clichés. The spiritual film idea, if it has any plausibility, helps to explain why the locations where ghostly activity is reported are often much more mundane. While railway locations such as tunnels, the overgrown formation of long-abandoned lines and closed stations in particular do seem to provide ideal scenarios for paranormal comings and goings, reports often come from everyday places such as level crossings, signal boxes, station footbridges and even the interior of well-occupied railway carriages.

We believe that some honestly presented reports of strange phenomena have unknown but entirely simple and everyday explanations. People subjected to experiences involving extreme emotions such as terror may not be reliable witnesses. Some reports are made by people seeking attention and publicity – a few days of capricious celebrity. Other reports are the work of deliberate hoaxes or sometimes of people who have allowed their imaginations to run away with them. With the stories mentioned in this book, we believe that the people involved genuinely experienced or sensed something odd. What that might be is not easily explained, and, of course, may not have been anything to do with the paranormal. We want to let the stories do the talking and we try to provide some historical background and railway detail as appropriate.

The railways of Britain cannot be seen in isolation. They were both a product of and a major contributor to the complex set of interacting economic and social developments which historians conveniently call the Industrial Revolution. This was the starting point of the modern world. The railways, in conjunction with the electric telegraph which was developed as an aid to safety, initiated the revolution in high-speed communication and transmission of information which continues to this very day. Of the early railways, the most significant was almost certainly the Liverpool & Manchester, opened in 1830. This joined two of the north’s most important cities, was designed to use steam locomotives from the start and was soon bringing real economic benefits to the industrialists of south Lancashire and Merseyside. It also had one almost totally unexpected effect – it showed that there was a market for people to travel just for the sheer pleasure of travelling.

A tunnel ghost? Or a little photographic sleight of hand?

Right from their inception, the railways elicited mixed responses from the public. Some regarded the steam locomotive as a frightening fiery devil, it and the iron road it ran on being unwelcome intruders into the placid English countryside, while others were fearful of its speed, of its lofty viaducts and especially its baleful tunnels. There were those, however, who found railways exciting for bringing places which had been distant closer together and for opening up opportunities for travel and adventure.

Any train, especially a steam train, takes on a more mysterious and romantic aura after dark, and many of the stories which follow are about experiences that occurred at night. Surprisingly, perhaps, there are relatively few good ‘factual’ railway ghost stories, given the social, cultural and wider impact of the railways. We have produced a selection of these, but omitted many where the phenomena described have been the same or very similar to the ones we have chosen, and we make no claim to providing a comprehensive guide to such tales or for an even geographical spread. Tunnels and signal boxes feature extensively, as do many level-crossings. Did the crossing-keeper go by the name of Charon?

We will leave this introduction with the words embossed on a cast-iron notice of the Great Northern Railway near Stafford, on its branch line from Derby and Uttoxeter. It was to be observed by engine drivers, and it read: ‘Whistle at Cemetery Crossing’.

List of Locations

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

High Wycombe

CAMBRIDGESHIRE

Conington

Peterborough

Soham

Yarwell Tunnel

CORNWALL

Bodmin Road

St Keyne

COUNTY DURHAM

Darlington, North Road Station

CUMBRIA

Lindal Moor

Maryport

Tebay

DERBYSHIRE

Chesterfield

Tunstead Farm

DORSET

Bincombe Tunnel

GLOUCESTERSHIRE

Charfield

GREATER LONDON

Addiscombe

GREATER MANCHESTER

Ashton Moss

Bradley Fold

Manchester Mayfield

HAMPSHIRE

Hayling Island

Swanwick

HERTFORDSHIRE

Hatfield

ISLE OF WIGHT

Newport

KENT

Pluckley

LANCASHIRE

Bispham

Entwistle

Helmshore to Ramsbottom

LEICESTERSHIRE

Rothley

LINCOLNSHIRE

Barkston

Bourne

Claxby & Usselby

Elsham

French Drove

Grantham

Grimsby

Hallington

Hibaldstow Crossing

Tallington

MERSEYSIDE

James Street

Walton Junction

NORFOLK

Abbey & West Dereham

NORTH YORKSHIRE

Middlesborough

Sandsend

NOTTINGHAMSHIRE

Burton Joyce

Mapperley Tunnel

Rolleston

OXFORDSHIRE

Shipton–on–Cherwell

SHROPSHIRE

Shrewsbury

SOMERSET

Dunster

Stogumber

Watchet

SOUTH YORKSHIRE

Beighton

Hexthorpe near Doncaster

SUFFOLK

Bury St Edmunds

Felixstowe

Sudbury

SUSSEX

Balcombe Tunnel

Clayton Tunnel

West Hoathly

WEST MIDLANDS

Coventry

WEST YORKSHIRE

Clayton

Haworth

Huddersfield

Otley

Wakefield Kirkgate

Yeadon

WILTSHIRE

Box Tunnel

Monkton Farleigh Mine

WALES

Saltney Ferry

Talybont–on–Usk

SCOTLAND

Auldearn

Dunphail to Dava

Kyle of Lochalsh

The Glasgow Subway

Pinwherry

The Tay Bridge

The Waverley Route

GHOSTS OF THE LONDON UNDERGROUND

Aldgate

Aldwych

Bakerloo Line

Bank

Bethnal Green Station

British Museum

Covent Garden

Farringdon

Jubilee Line

Kennington

Liverpool Street

London Road Depot

Marble Arch

Moorgate

Vauxhall

Closed Railway Stations

Crystal Palace

Defunct Underground Stations

‘Ghost’ Steam Trains

1

The Stories

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

High Wycombe

The first railway at High Wycombe was the Wycombe Railway, opened in 1854 from Maidenhead via Bourne End. It was leased to the Great Western Railway (GWR) and extended in 1862 through Princes Risborough to Thame, and later to Oxford. Subsequent lines gave High Wycombe direct services to Banbury, Leamington and Birmingham on the GWR, to Rugby and points north via Ashendon Junction and Brackley, by courtesy of the Great Central Railway, and to Paddington via Beaconsfield over the line of the Great Western & Great Central Joint. The line through High Wycombe is still operational.

One night a railwayman had been having a drink or two with friends in a pub close to High Wycombe Station. Tearing himself away from the convivial company, he made for the station to catch a late train home to Beaconsfield. There were few people about at this time of the night, the station was quiet and the platform for his train was completely deserted when he got there. He had a few minutes to spare before the train was due. He then heard footsteps crunching along the ballast at track level. They approached and passed close by with no one visible to make the crunching! He heard the distinctive sound retreating into the distance, only to stop abruptly when some other passengers arrived on the platform. His train ran in and soon deposited him at Beaconsfield. He was not drunk nor was he given to flights of imagination but it was a puzzled and confused man who made his way home that night.

He often used High Wycombe Station and he knew several of the staff there. He hadn’t been at all frightened by the strange invisible footsteps, but he couldn’t get the experience out of his mind. He had little time for notions about ghosts and spooks and prided himself on being rational and level-headed. The next time he was there he mentioned what he had heard to one of the ticket collectors. This man didn’t bat an eyelid. He and several other members of staff had heard the same disembodied footsteps. From time to time when the station was quiet, footsteps marched up to a particular door, and when the railway worker inside opened it, there was no one there. The men who had these experiences all thought a ghost was responsible but, oddly, none of them had ever felt frightened. After this, our man from Beaconsfield was never quite so adamant that ghosts were all products of the fevered imagination.

CAMBRIDGESHIRE

Conington

Conington is a small village, little more than a hamlet, and is close to the Great North Road about seven miles south of Peterborough. The very fine parish church of All Saints is some distance from the village and it possesses an especially magnificent west tower from about 1500 which can be seen, embowered in trees to the west, by travellers on the East Coast Main Line. Conington Crossing is something over a mile east of the church. It has the reputation of being haunted.

In March 1948 a light engine on the main line hit a lorry carrying German prisoners-of-war on this crossing. They were being taken to work on local fenland farms, and the accident which led to six of them dying happened at seven in the morning, on one of those days of dense fog that used to be so characteristic of this area. Later in 1948 an eminent citizen of Peterborough had been shooting in the fens with a companion, and he was killed instantly when his large and distinctive black Chrysler car was hit by an express train as it made its way over the crossing. On this occasion the visibility was excellent.

These two accidents followed any number of hair-raising narrow escapes over the previous decades, and a few fatalities. The road over the crossing was a very minor one which led to little more than a handful of farms, and traffic was very light. However, there was at that time no signal box to control the crossing and users had to open and close the gates as well as to get themselves across, exercising extreme vigilance because of the frequency and the speed of trains at this point. Unfortunately, users of the crossing were not always as careful as they needed to be and they sometimes took undue risks or forgot to close the gates after them. Footplate men on the locomotives that worked this stretch of line hated the place which had gained the reputation of being a serious danger spot. Pressure developed and eventually British Railways built a signal box to control the crossing.

Conington Crossing is remote, quiet and lonely. A shift at the new box, especially the shift between ten at night and six the next morning, was no sinecure. Trains were frequent, although people or vehicles wishing to cross the line were few. What made working the box such a challenge were the strange occurrences recorded by the signalmen. It didn’t help that bitter winds howled across the fens, ‘straight from Siberia’, as they say in those parts, and they made the gates and other items of equipment rattle in a disturbing way. Several signalmen reported the appearance of a large black limousine, clearly waiting to cross the line. When they went to open the gates, however, the car vanished. This weird and irritating event happened several times. The car did not restrict its appearance just to the hours of darkness; when it turned up during the day it still waited for the gates to be opened, but disappeared as soon as the signalmen went to do so. All were agreed that this was the black Chrysler which, with its occupant, had returned to the scene of the fatality. This spectral car was unnerving enough in its own right, but the local word was that the crossing was also haunted by the ghosts of the German prisoners-of-war. Some signalmen refused to work the box, especially on the night shift.

Conington Crossing is still there with or without its ghouls and spectres but the signal box was closed and demolished in conjunction with the establishment of a high-tech signalling centre at Peterborough in the 1970s. To this day, few people who know the area will volunteer to hang around at Conington Crossing, especially after dark.

Peterborough

In 1945 a married couple who lived in North London decided to visit relatives who lived in Newcastle-on-Tyne. The war was over and people just wanted things to get back to normal as quickly as possible. Many of the restrictions on travelling had been lifted, but the railway system was sorely run-down. Maintenance work had taken a back seat in the attempt simply to keep the vastly increased number of trains moving that were needed to support the war effort. Part of getting back to normal was to visit faraway relations, something that had been more-or-less impossible for the duration of the war.

The couple were not fond of train travel and so were looking forward somewhat glumly to the journey, expecting the train to be dirty, late and overcrowded. This had inevitably become almost the norm over the previous few years. They were therefore pleasantly surprised when they got to King’s Cross not only to find their train with ease but to get seats in an otherwise unoccupied compartment. The train itself seemed reasonably clean, even to their somewhat jaundiced eyes. Not for them the pleasures of watching the moving scene as the train, headed by a Gresley A3 4–6–2, steamed northwards. They had bought a pile of newspapers at W.H. Smith to relieve the tedium of the journey.

Serried ranks of tall brickyard chimneys and a sulphurous smell indicated that the train was approaching Peterborough, its first booked stop. The train drew to a halt, there was some activity on the platform and passengers were walking up and down the side corridor. The compartment door slid open and an elderly lady entered carrying a sizeable wicker basket. She smiled at the couple and then sat down without saying a word. Her appearance had quite an effect on both husband and wife, although it was the wife who took in the details of the newcomer’s appearance most keenly. The newcomer was dressed from head to toe in black. Her clothes were elegant and clearly of the highest quality. However, she was a walking anachronism! Every inch of her gave the impression of a prosperous Victorian lady of fashion. She looked very composed as she sat in the opposite corner, her face partly obscured by the brim of her sumptuous hat.

Grantham was the next stop and the train halted long enough for locomotives to be changed. The man decided he had time to get some tea from the refreshment room and he bought three cups – it was a kind thought that perhaps their new travelling companion might appreciate something to drink. He returned to the compartment and offered her one of the cups, which she took with a smile but, perhaps strangely, without saying anything.

Further calls were made at Doncaster, York and Darlington, but no one disturbed the silence in the compartment. Husband and wife continued to read the papers or to doze fitfully. The woman sat motionless, eyes closed. Every so often the man would peek at her. He didn’t know exactly what it was but there was definitely something odd about her – odd, that is, apart from the outdated fashion she sported. As the magnificent cathedral at Durham came into view, standing with the castle as its companion on the great rocky bluff above the River Wear, it was clear that this was where the woman was intending to leave the train. The man, ever gentlemanly, slid back the door for her and gestured that he would carry her basket. She smiled graciously, but without speaking, and stepped down onto the platform. The basket was strangely light, given its size. He handed it to her whereupon she spoke for the first time. ‘I wish you many happy years,’ she said. Having uttered these slightly enigmatic words, she vanished into thin air! Who was the lady in black who got on the train at Peterborough, sat in the compartment of the East Coast Main Line train and alighted at Durham that day in 1945?

Soham

On 2 June 1944, the 00.15 special freight train from Whitemoor to Earls Colne was travelling along the line from Ely to Fordham, approaching the small fenland town of Soham at around 03.00 a.m. Driver Gimbert, aboard a W.D. 2-8-0, looked back and noticed that the wagon behind the tender was on fire. The train’s payload consisted of bombs! Thinking quickly, but not panicking, Gimbert slowed the train and instructed fireman Nightfall to climb down and uncouple the wagon that was alight. This he did, and when he regained the footplate, locomotive and blazing wagon were moved forward. The Soham signalman was standing on the platform and Gimbert told him that he intended to haul the wagon into a cutting just ahead where the force of any detonation, if one happened, would be at least slightly reduced. No sooner had he informed the signalman to this effect than an enormous explosion occurred. The wagon was reduced to matchwood, the locomotive severely damaged as it was blown off the rails, Fireman Nightfall was killed instantly, the signalman received injuries from which he died shortly afterwards and the 18-stone Gimbert was propelled through the air for a distance of 200 yards, sustaining serious but not life-threatening injuries.

Soham Station. This neat little station disappeared in the explosion.

There is no question that had Gimbert and Nightfall not taken the action they did, the entire train might have blown up and Soham would have been obliterated. As it was, almost every window in the town was broken and nearly every house received some damage. For their heroism Gimbert and Nightfall received well-deserved George Crosses, that for Nightfall unfortunately being posthumous. Their valour was recognised decades later when each of the men had a Class 47 diesel locomotive named after him.

It has been claimed that part of this drama is re-enacted in ghost form annually on the anniversary of the Soham Explosion. A steam locomotive hauling a freight train arrives at Soham from the Ely direction and is then detached. The apparition ends by simply fading away. Fortunately the explosion is not re-enacted. The line through Soham is still operational, although the station closed many years ago.

Yarwell Tunnel

The attractive stone-built village of Yarwell is in Northamptonshire, but Yarwell Railway Tunnel is in Cambridgeshire. The tunnel was on a long branch line to Peterborough from Blisworth, on what became known as the West Coast Main Line. This cross-country route served Northampton, Wellingborough, Thrapston and Oundle. The line was built by the London & Birmingham Railway and opened to passenger traffic in June 1845 and goods traffic in December of that year. This was unusual. Usually lines opened for goods traffic before receiving official approval to run passenger trains.

The tunnel is over 600 yards long and provided a variety of problems during its construction. Conditions on the railway construction sites would have driven today’s health and safety officials apoplectic. Deaths occurred among the navvies and labourers employed on the works. Some may have resulted from drunken brawls out of working hours. It was by no means unknown, however, for the navvies to work while inebriated. They did the hardest and most skilled work, and it was part of their laddish culture to take risks and cut corners. Doing so when drunk, of course, only made the dangers worse.

Whether it was the ghosts of the navvies making their presence felt we will never know, but men involved in maintenance work in the tunnel over the years told stories of the strange noises they heard. These included what sounded like fights, cries of pain, groans and various unidentifiable sounds. They made the tunnel an unpleasant place in which to be alone, although fortunately they usually did their work in small gangs. Also inexplicable was the disappearance of tools and pieces of equipment that would have been of little use to anyone else. A new piece of track laid on one particular day was found the following day having apparently been tampered with overnight. Many of the wooden keys strengthening the joint between the rails and the iron chairs spiked to the sleepers had been removed. This would have made the track unstable and could have led to an accident.

When work was being carried out on the track in the tunnel, it was customary to post lookouts at both entrances to give warning of an approaching train. On one occasion a gang was busy in the tunnel when a freight train rushed in, despite the fact that no warning had been given. Fortunately there were no injuries, but the men were somewhat shaken by the experience and they rather indignantly wanted to know why the lookout apparently hadn’t been doing his job properly. They found him lying by the side of the track, uninjured but unconscious. When he came round he told the others that he had received a stunning blow on the head which knocked him out. This was puzzling because a doctor called to the scene could see no evidence of a blow. Equally puzzling was the fact that the lookout’s equipment was also missing.

Wansford Station is not far from the eastern end of the tunnel. A past stationmaster used to carry out his duties almost always accompanied by his cat, Snowy. One early evening Snowy very unusually couldn’t be found when it was time for his dinner. Having waited for an hour or so, the stationmaster decided to have a look at all the places where he knew that the cat liked to go. One of these was the tunnel, and the stationmaster entered, calling out Snowy’s name. The man was near retirement and had become somewhat deaf, and unfortunately he was struck down by a train and killed. Snowy never reappeared. Since the tragedy, a cat answering Snowy’s description has been seen on occasions mewing pathetically at the entrance to the tunnel of ill-repute. Or is it the ghost of Snowy?

Chester Station looking north. Nearby on the left stood a lead works. An employee there was killed on the railway and his ghost returned to stalk the works until they were demolished and houses built on the site.

Passenger services through the tunnel on the Northampton to Peterborough route ceased on 2 May 1964 and those from Rugby to Peterborough finished in June 1966. Ironstone trains to Nassington ceased from December 1970 and vestigial freight services as far as Oundle on the Northampton line ended in 1972. However, all was not lost; the eastern end of the line from Peterborough eventually became the Nene Valley Railway, a heritage line unusual in that its loading gauge allows it to operate continental rolling stock. Trains began to run through the tunnel on a regular basis again in 1984.