Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

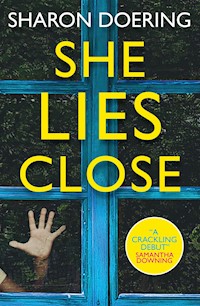

Five-year-old Ava Boone has been missing for six months. There have been no leads, no arrests. The only suspect was Leland Ernest. And mother-of-two Grace Wright has just bought the house next door. With whispered neighbourhood gossip and increasingly sleepless nights, Grace develops a fierce obsession with Leland. Could she really be living next door to a child-kidnapper? Or worse a murderer?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1. Teenage Boys Descend Upon Me

2. That Sac Was the Worst of Surprises

3. Shrink This Woman

4. The Skin Peeled Back

5. A Game of Hedge-Clipper Tag

6. Peace Be With Your Vagina

7. Ferret Out the Asshole

8. I Know More Than I Should

9. House Burned to the Ground

10. Twist the Handle on My Front Door

11. We Don’t Bite

12. Pussy Puss

13. A Fucking Marble in the Mouth

14. Oh, That Kind of Monster

15. The Psychic Party

16. Emptying a Bottle of Bleach on Them

17. Exploding Head Syndrome

18. Eat Someone’s Whole Head

19. A Shitty Alternate Version of the Velveteen Rabbit

20. Holed up in a Log Cabin off Grid

21. Cross-Species Love

22. And What Did You Do?

23. A Starchy, Scratchy Grave

24. Occasionally I Have a Hula Hoop Around My Neck

25. This Won’t Hurt a Bit

26. My Vagina Was Made in China

27. A Crowbar, a Credit Card, and a Hammer

28. Lead Glass, Chipped Bone, and a Splash of Antifreeze

29. Fuck Lynyryd Skynyrd and Their “Free Bird” Nonsense

30. His Fingernails Dug in

31. The Shitfaced Toddler Has Fallen Asleep on a Pile of Stuffed Animals

32. Brand New Tattoo Engraved in My Skin, Just Beginning to Bleed

33. Ripped Open This Dimension to Ooze Blood Into My Car

34. A Woman’s Voice Says to My Ass

35. A Middle-Aged Monster

36. Demons Sent From Underground Hell-Caves

37. The Boy-Doped Silliness I Smoked

38. You Broke My Nose

39. Lose a Few Toes

40. Play, Pause, Rewind, Play

41. Copper and Iron and Animal

42. Are My Socks Wet?

43. Some Sort of Explosive Device

44. The Porn Cop

45. Filthy, Lazy Crybabies

46. They Fed on Him

47. I’ve Been Hiding My Penis

48. Ripped From My Mother’s Womb

49. Trap the Warm, Struggling Body Inside a Plastic Storage Bin and Fasten the Lid

50. A Shadow Database

51. When the Stovetop Is Flaming

52. They Know Who Did It

53. Fishbowl Glass Gems Go Flying

54. Wiggling His Fingers Into Latex Gloves

55. Hijacking Our Behavior

56. Put on a Diaper and Head to the O.R.

57. A Hysterical Bitch Who Had No Faith

58. Judge, Jury, and Executioner

59. Do. Not. Fall. Asleep.

60. Her Vertebrae Were Yanked by a Hook

61. A Twisted Scavenger Hunt

62. Bring on the Drugs and Drag Racing

63. Under My Skin

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“Every curve, every twist takes you further down the rabbit hole. Sharon Doering has written a crackling debut that should be on your 2020 list!”

SAMANTHA DOWNING

“If you love Gillian Flynn, you will love this book”

Manhattan Book Review

“An explosive, darkly comedic thriller that belongs on every to-read list. Scrupulously plotted… She Lies Close is a live wire of a debut”

MARY KUBICA

“Grabbed me from the first page and wouldn’t let go. A fast-paced, taut, psychological mind-bender that hits all the right notes”

D.J. PALMER

“Dark, searing, and raw… A no-holds-barred debut that builds tension and suspicion, culminating in an ending that will shake you to your core”

SAMANTHA M. BAILEY

“A chilling twister of a thriller...Smart, compelling, and darkly funny”

LISA UNGER

“Packed with chills, and an unexpected ending that readers won’t see coming… A writer to watch”

JOANNA SCHAFFHAUSEN

“The perfect blend of dark writing, gripping characters and gasping twists that will keep you reading late into the night”

SHERRI SMITH

“A terrifying yet deeply affecting exploration of how far a mother will go to protect her children. Fascinating and unforgettable”

SOPHIE LITTLEFIELD

“A beautifully written debut thriller – vivid storytelling at a breath-taking pace”

ALICE BLANCHARD

“A gritty and engrossing thriller…You’ll be trying to both savor every word and turn the page as fast as possible!”

JENEVA ROSE

“A psychological thriller unlike any you’ve read before. A perfect mixture of chilling suspense and twisting family secrets”

JAMIE FREVELETTI

SHE

LIES

CLOSE

SHE

LIES

CLOSE

SHARON DOERING

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

She Lies Close

Print edition ISBN: 9781789094190

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789094206

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2020 Sharon Doering

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us [email protected] or write to us atReader Feedback at the above address.

TITAN BOOKS.COM

For Marc,my muse

For Jon, Sam, and Ed,my heroes

PROLOGUE

He’d brought a spade instead of a shovel. It had been a stupid, panicked mistake. There’d been a gang of dirt-breaking tools, all wood-handled and rusted, leaning against the wall in the garage, and he’d grabbed one without thinking.

Mud made for stubborn digging, and the spade would only stretch the work. As he thrust the square blade into sludge, his back muscles twitched and his pulse thumped in his neck. Rain dripped into his eyes, stinging.

He’d been crazed and incoherent an hour ago, his throat still felt clawed from screaming, but now his mind felt strangely calm. Hollow.

He wanted to pull the blanket away.

Don’t.

The night was cold enough for his breath to cloud the air, and his clothes clung heavy with rain, yet his skin itched with heat. Inside his gardening gloves, his hands sweat.

Don’t look.

Here among the trees, the rotting stench of detritus was thick in the back of his tender throat. And he was hearing too much: the sizzling, frying-oil sputter of rain; chirping crickets; and his own breathing, heavy and animal.

Don’t look under the blanket.

Tilting the spade and pitching mud into a pile, he felt something come loose from the back pocket of his jeans. He reached back, trying to catch it, a muscle memory reaction from always carrying his phone in his pocket, but missed. It hit the forest floor with a subtle thump.

What had he dropped?

Blue moonlight filtered through the leaves of scrappy young trees. He wiped sweat and rain from his eyes with his shirt sleeve and squinted.

A small slip-on shoe, red and sparkly.

1

TEENAGE BOYS DESCEND UPON ME

My mind is a snow globe in the hands of a toddler who’s shitfaced on apple juice. I keep waiting for the white flakes to settle, but they remain a perpetual, furious blizzard.

* * *

Exhausted and wired, I sprint through muggy darkness. Baby monitor in one hand, cell phone in the other. My cheap foam sneakers pound cement sidewalk, and my unsupported arches stretch and twinge. I suck the humid stink of late-summer compost deep into my aging lungs. Why does life smell so bad?

I corner the block, and the white-noise static of the baby monitor zaps to silence.

Out of range.

I run faster. If I push it, I can run an eleven-minute mile. That’s one lap around my block. My heart bangs against its cage, and salty tears slip onto my tongue. Crying is part of my routine too.

My neighborhood, Saint’s Crossing, was built quick and dirty thirty years ago. At least that is what a plumber told me when I hired him to fix the second-floor-bathtub-leaking-onto-my-kitchen-table problem.

Houses on my block are modest and cozy. Or small and ugly. Depends on your perspective and mood. In daylight, their colors are typical midwestern drab: tan, sage green, and pale yellow. Trees dotting small lawns and parkways are too large and too many. Tricycles and coffee tables are occasionally left on curbs, offered for second-hand use. Saint’s Crossing is a neighborhood of families, young and old, but most of all it seems down-to-earth and safe.

Or so I thought when I moved in several months ago.

I reach the furthest point away from my house. This is when fear and guilt sink their nails into the back of my neck because I’ve left my sleeping children home alone.

Well, Hulk is with them. She’s a Boston Terrier. Think tiny dog with pointed, upright ears and bug eyes. Of course she has no thumbs to dial 911, but she would get in a few good barks if an intruder broke a window. Before he offered her food.

This is when I worry my three-year-old has woken up and is wandering the house, rubbing her chubby little thumb along her square-foot blanket, tears streaking her irresistible cheeks.

This is when I agonize most over Leland Ernest, my next-door neighbor.

A mosquito buzzes my ear, and I smack it.

A towering lamppost casts shadows of trees onto the sidewalk. A slight breeze gives the leaves breath and shapes the branches into yawning monsters. My shadow, a twelve-foot giant, tramples these sidewalk beasts.

Leaving the lamp’s glow in my wake, I run toward a long stretch of houses whose owners zealously oppose porch lights.

A low branch whips my chest and spikes my pulse. I didn’t see it coming. These late-night sprints around the block are a rush. I never know what’s going to smack me in the face or if an uneven sidewalk crack will snag my shoe and take me down.

Homestretch—exactly fourteen houses away—I pump my legs harder.

Strides ahead, an obese pine tree overruns the sidewalk.

As I sidestep the pine, a black shadow erupts from high in the tree and, swooping down, claws at my neck.

The impact throws me off balance. I fall onto dewy grass, and I piss my shorts. Sounds of static and clicking scatter into divergent points of noise overhead.

What the hell hit me?

Felt substantial, like a squirrel.

But that makes no sense.

Bees. Had to be bees.

Bees make sense because pin-prick points along my neck and shoulder sting and burn. My fingers search my neck for stingers, but only slide along wetness. Sweat. Maybe blood?

I picture a swarm of bees crashing into me, fleeing their hive because some old guy pesticide-bombed the co-op they’d built near his front door.

But… do bees screech?

As I sit in my piss-shorts in the grass and breathe in an effort to prevent hyperventilation, two teenage boys descend upon me, touching my damp back and shoulders with their nicotine-rubbed fingers.

“Dude, are you alright?” His voice is part hilarity, part grave concern. Oh please, call me anything but “dude”. Have I lost all markers of femininity? My eyes work to make out his face and shape. He is teenage-skinny, has a boy’s crew cut, and strikes me as military-confident. “That was sick. Way sick,” he says.

His friend, wearing a baseball hat over shoulder-length hair which feathers beautifully, shakes his head silently, mind blown.

I run my fingers through cool, wet grass, searching for my belongings. Beyond their cigarette-smoked clothes, fabric softener laces the air. Someone is running their dryer.

“I’m OK. I’m not sure what happened,” I say, embarrassed at the extent of my disorientation and glad for darkness. Even if they catch a faint whiff of urine, they can’t see my wet shorts. “I think I got stung by bees.”

“Dude, those were bats. Like, twenty little fuckers. They came out of nowhere. Swoosh. Went that way.” He points across the street as if it matters, as if we could see anything in this darkness. As if the bats were waiting on cue for an encore.

Bats? Is he kidding?

If there is one thing I can’t stomach at this moment in my life, it is to be fucked with.

I consider the situation. Whatever hit me had bulk. I consider the quality and tone of the screeching. Maybe I heard flapping. I can’t remember, it happened too fast.

I gaze up at him, checking if his lips curl up at their corners.

No curl. His lips are parted. He’s out of breath too.

Not fucking with you. It was a pack of bats. Pack? Roost? Colony?

His quiet friend with feathered hair is still shaking his head, no sign of stopping.

“I didn’t know bats sounded like radio static,” Crew Cut says. “Can we call someone for you?”

“I’m OK. Really. I live a few houses away.”

Getting knocked over by small flying things while pursuing physical fitness is embarrassing. I feel geriatric and uncoordinated and smelly, and desperately want to slither into darkness. I stand and take a few rubbery steps, then shift into a jog.

His voice already a house behind me, he calls, “If you get a craving for blood, you know why.”

I swallow, but my throat is dry, and it doesn’t take. Hot wind blows at the scratches along my neck, drawing a sting.

Shit. Bats carry rabies.

2

THAT SAC WAS THE WORST OF SURPRISES

Hulk is thrilled by my pee-shorts. As if someone finally understands her disgusting compulsions.

I shower and pull on yoga pants and a T-shirt. Wet hair dripping down the back of my shirt, I grab my laptop and google, “attacked by bats”.

Five minutes online and I’m bleary-eyed, brainstorming my eulogy. Without immediate treatment, rabies is fatal nearly one hundred percent of the time, and, for some cracked reason, the upscale neighborhood north of mine currently has a bat problem. The flying, pug-nosed vermin have been found inside homes, and sixteen bats have tested positive for rabies this summer.

I’m about to call my mom, but stop. It’s hours past her bedtime. I mentally scroll through a short list of friends. Liz lives thirty minutes away. Too much to ask. As for the others, I haven’t seen or talked to them in how long? Weeks? Months? I tell myself not to worry, not to question friendships. All these women are busy juggling work, children, cooking, and cleaning and have neglected their friendships, their sex lives, and, occasionally, their basic hygiene.

Valerie is only fifteen minutes away and never misses a text.

-Valerie! I know it’s super late, but I need you to watch my kids for 30 min.

-Booty call?

-Funny, no. Bats. I need a rabies shot.

-You’re joking.

-No. Need go to ER asap.

-Seriously?

In lieu of response, I send her a photo of my neck.

-Be there in 20. Need to find glasses.

Valerie arrives at my door wearing her glasses slightly crooked upon her nose, flannel PJ bottoms, and flip-flops. Her threadbare Eminem T-shirt stretched tight over her belly and breasts reveals she hasn’t bothered with a bra. One nipple lands a solid inch lower than the other. I am all too familiar with this boob asymmetry, and it makes me love her more.

“I’m sorry to pull you away from Dan on a Saturday night,” I say.

Bugging out her eyes, she makes a raspberry noise with her lips, and a sphere of spit lands on my arm. “Oh please,” she says. “He’s eating hummus from a spoon in his boxers, watching Curb Your Enthusiasm reruns. I’m not into any of those things.”

“Thank you.”

See, your friendship hasn’t missed a beat.

She makes another raspberry noise. “Seriously, it’s nothing. Let me see your bite.”

“They’re scratches, I think.” I bend my neck so she can see. “I need to get the vaccine just in case.”

“Wait! Are they in your house? The bats?”

“No, no. I was outside. I was jogging.”

She raises her eyebrows. “You left the kids home alone?”

“I only did one lap around the block,” I say but I am caught. My brief, late-night parental negligence has been secret. Now my impropriety will be known, will be questioned.

“I should go,” I say, hiking my purse over my shoulder. “Chloe and Wyatt are sleeping in their beds.” I go for the door, then turn around. “Listen. When I leave, keep the doors closed and locked.” I dig my keys out of my purse and rattle them, stalling, considering what I want to share with Valerie. “My neighbor is a suspect in a criminal case.”

Kidnapping.

Although, at this point, five months in, it has probably turned into a murder case. But I don’t want to say murder. I’m not ready to say murder.

My disclosure feels stagy and unnecessary, but my neighbor’s criminality has been a cloud of noxious fumes—something godawful like burning PVC—trapped inside my mind for days, and I have been desperate to vent. And Valerie should keep the doors locked. What if she was planning to lie on my couch with the front door open, warm summer breeze breathing through the screen?

“What criminal case?”

“Ava Boone.”

“Oh my God, Grace. Ava Boone? Oh God. That poor angel.” Valerie claps her hands to her cheeks and drags the skin down, nudging her glasses straight in the process. “That poor baby should be starting kindergarten like my Max. This is crazy. Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I only found out a few days ago.”

“Why is your neighbor a suspect?”

“I don’t know all the details,” I say, which isn’t exactly a lie. “He’s probably innocent. They haven’t arrested him, right? He’s probably a good guy.” I’m trying for optimistic, I’m championing devil’s advocate, but my voice wavers because he’s not a good guy. “I’m just being on the safe side.”

“Safe side? Ditching your kids to go for a jog? What were you thinking?” She’s not patronizing me or being a dick. It’s a fair question.

I have several answers, each of them honest.

1. Thinking? I was barely thinking. These past four days my mind has been sticky with cortisol spooge and desperate for an eleven-minute brain-bath of dopamine clarity.

2. I have not slept in four days. I was hoping physical exertion would lead to sleep.

3. I haven’t had sex in six months and needed some form of physical release.

4. Chloe took a photo of me last week. Actually, she took twenty-five. A series of snapshots beginning with sneaking my phone off the counter as I washed dishes and ending with her getting a purely joyful tickling on the couch. I thought I was pulling off forty. These photos were a slap in the face, twenty-five of them. The first few photos showed my ass sagging in gray yoga pants and the outline of my underwear inches below where said ass is supposed to end. The next dozen photos highlighted underarms so pale, doughy, and mottled, they made me want to give myself plastic surgery with a butter knife. The final shots showcased my oily, creased forehead and greasy hair and this lumpy scrotal-like sac under my jaw I had no idea existed. That sac was the worst of surprises. That I appear happy in the photos, deliriously happy, as I tickle my pint-sized trouble-maker, counts for nothing. The ugliness her photojournalism displayed whites out everything. I remind myself, Mom ranks as “most searched” on porn sites. Doesn’t work. Nothing will boost my ego. Bottom line: exercise was needed.

I go with the easiest answer. “I haven’t slept in four days, Val. I was trying to knock myself out.”

“They got drugs for that. Or why not polish off a bottle of wine? That’s what I do.” She shakes her head, dumbfounded, same as the long-haired teenage boy. “Didn’t you check the neighborhood before you bought?” There is support and concern in her voice, but also judgement. What kind of idiot mother are you?

“I checked the predator site, but what else can you do? Go door to door, asking if anyone’s a suspect in a kidnapping? He’s not convicted of anything. She’s still missing.”

“Missing?” she says. “You know seventy-six percent of kidnapped girls are murdered in the first three hours.”

Seventy-four percent, according to my Google search. “I know. I should go, Val.” She’s put me on the defense, which I hate. And my neck stings. Images of the water-fearing, rabies-infected Indonesian teenage boy I saw on YouTube resurface.

“You’re right, you should go,” she says. Then, “Do the kids know?”

“Not yet, no.”

“OK, you go.” Avoiding the mangled side of my neck, she hugs me quickly, but generously. A good hug. One that makes me realize I am in serious need of adult contact.

Wyatt’s eight-year-old hugs are few and far between, and when he gives them, he turns his face away from my eyes and my clothes as if the smell and the sight of me is unbearable. Before the hug even begins, he is pulling away.

Chloe’s three-year-old hugs are communion, all fluttering butterfly hands and moist skin, but they are also greedy. Chloe is known for holding my face between her grubby palms and squeezing hard. If she can’t reach my face, she is on my leg, her small hands grabbing the cellulite on my thighs.

Kids are takers. They poke their little straws into your Capri Sun soul and they suck.

I drive myself to St Joe’s hospital with my window down. Warm breeze blows at my face, cooling my cheeks, but my scalp is sweaty and tingly.

Hospitals make me nervous. It’s a phobia, really. Driving to one is akin to nearing the front of the line for a haunted house. Not a cutesy haunted house targeting a wide-eyed middle-school audience, but one that indiscriminately employs thirty-year-olds with criminal records and runs extension cords to power real chainsaws.

The last time I went to a haunted house, I elbowed a zombie in the jaw and knocked him over a coffin. I hope I can keep my hands to myself at St Joe’s.

3

SHRINK THIS WOMAN

The soapy, metallic scent of Betadine is up my nose.

I am on my back, shirt off, bra on, shivering. The hospital air is chilled. Plus, I’m anxious.

The ubiquitous white tissue paper crinkles beneath me as I wiggle slightly on the narrow bed. My ER room is partitioned by a modern sliding glass door behind a curtain.

“These don’t look like bat bites. More like scratches,” the woman doctor says. She told me her name a minute ago, but I’ve forgotten. Blue gloves on, she wipes my broken skin with Betadine, which is shockingly cold, and sets the yellowed cotton ball refuse on a tray.

My doctor is slender and has straight blond hair with seemingly natural highlights. Like a child. Her gorgeous hair is swept back into a ponytail so smooth and flawless, I am mystified. She is not conventionally beautiful and has no curves to her body, but her complexion is clear, her teeth are white, and her nose is petite. These features—natural highlights, dainty nose, small pores—are the bland features women like me covet as we get older and have to exert effort to keep masculinity from creeping into our faces.

“Yes, scratches,” I say. “That’s what I was thinking.”

“You could get rabies if one of the bats had saliva on its claws and that bat also had rabies,” she says. “Those are very low odds. Only six percent of bats have rabies.”

She finishes cleaning and bandaging my neck, then palms the garbage and throws it away. “Sit up, please,” she says, lifting the top of my gown off my lap and holding the armholes open. I do as I’m told. I sit, then slip my arms through.

She pulls a penlight from her lab coat pocket, clicks it on, and aims it at my eyes. “Follow my light. You say they attacked you?”

“I know. I know,” I say, tracking her light, “it sounds nuts. I must have been in their way as they flew by.”

“Hm.” She clicks her light off and slips it into her pocket.

“Two teenagers saw it happen.” Why do I feel like a child trying to prop a lie?

She shrugs like maybe she doesn’t believe me, but also doesn’t care. She finishes the standard six-point inspection checklist (respiration, pulse, eyes, ears, nose, throat) while she continues, “A dozen bats in the area have tested positive for rabies so we need to be on the safe side. We’ll give you the first vaccine tonight along with an antibody shot to prime your immune system. This is all standard post-rabies exposure protocol. You will make appointments before you leave for follow-up shots. You need to get them all within one month.” She makes eye contact and widens her eyes. Sclerae as white and healthy as her teeth. “I don’t want to scare you, but untreated rabies is fatal. If you finish the series of four shots, you will be fine. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Have you ever had an allergic reaction to a vaccine?”

“Not that I know of.”

The nurse who typed my information—name, birthdate, reason for visit—into her laptop minutes ago starts typing again, presumably recording my answer. The nurse is my age, maybe older. Her hair is curlier and messier than the doctor’s, the skin around her jaw and neck is sagging, but she has the same clear, efficient, kick-ass look in her eyes as her colleague.

“Have you ever been diagnosed with cancer?”

“No.”

“Heart disease?”

“No.”

“Have you ever had surgery?”

“No.”

“What medications are you currently taking?”

“Adderall.”

“For attention deficit?”

I nod.

Shame slides in like a sliver under a nail. It’s small, but poignant.

If I were on a cholesterol-lowering drug, would I feel ashamed by the profuse globular fat molecules bobbing slothfully through my blood? If I were taking asthma medication, would I feel ashamed by my melodramatic bronchioles?

I’m not sure, but I don’t think so. Lungs and blood are just lube and gaskets. The brain is a window into a person’s soul, their true state of being, internal strength, trustworthiness, and integrity. My brain, stripped down, without meds, is inadequate.

“How often do you drink alcohol?”

Would this question ordinarily come later in the questionnaire, but she moved it up in the queue in light of my attention deficit admission?

“Once a week, tops.”

“When you do drink, how many do you consume?”

“One or two glasses of wine, I guess.”

“Any other medical issues you worry about?”

This question bloats inside my head.

This would be a good time to tell her I haven’t slept more than a few hours in four days. This would be a good time to tell her that when I gazed out the window over the kitchen sink yesterday morning, the tip of a blue spruce tilted thirty degrees toward the ground before it righted itself. That hours ago when I was sitting on the toilet lid while the kids took a bath—with their ear-piercing laughing and shrieking amplifying off bathroom walls and water tsunami-sloshing out of the tub and onto a mess of towels and balled clothes on the floor—something inside me, some working part that’s supposed to remain fixed, free-fell for a moment. That I sense the vibrating strings interlacing the universe on the verge of ripping apart.

If I said these things, the doctor might document some tidbit that could force me to undergo some sort of mental therapy for which I don’t have the money or time.

You just need sleep.

“I haven’t been sleeping well lately so I don’t feel myself.” She waits, in case I want to reveal more. When I stare dumbly at her, my shoulders slouched, she says, “You can talk to your primary about a sleep aid like Ambien, but there are side effects. If you think your sleep difficulties are temporary, I would stick with Benadryl for a short-term solution. Always knocks me out.”

“Me too, but if I take Benadryl, I’m hungover in the morning and can barely make a sandwich for my son’s lunch.”

She smiles politely, but this is the ER. It’s all about turnover and, like a waitress already thinking about her next table’s tip, she wants me out. She rolls off her blue gloves and tosses them in the trash to indicate we are almost done here. “I’m going to grab the syringes, and then you’ll be all set. Do you have any questions?”

“I teach preschool. Can I go to work Monday?”

“Yes. You’ll be scabbed over by then. To be cautious, keep your scratches covered with bandages.” She smiles. “Were you hoping I’d ban you from work for the week?”

“No.” Her joke draws a nervous sweat from my skin, cutting to my insecurities regarding how I am perceived. Do I give off that white trash vibe? “Are the shots painful? In the stomach?” I’ve heard urban legends about rabies shots.

“No. Rabies shots haven’t been given in the stomach since the eighties. Just a shot in the arm. And I’ll inject antibodies near the wound. You’ll do fine.” She taps my knee once. “I’ll be back in a few minutes.” She pulls open the curtain, then the sliding glass door. She exits quickly, graceful as a dancer.

My kids’ vaccines are always injected by a nurse. That the doctor is preparing my vaccine makes the situation seem dire. Iodine soap stink hangs heavy in the air. My stomach is tight, my skin is cold and clammy. The ER is freezing.

“I am not making this up,” I say to the nurse.

She smiles and gently backhands the flab on my upper arm like we’ve been sitting at a bar together for hours. “You wouldn’t believe how many times we hear that in the ER. Guy came in last week with a peanut butter jar up his ass. Said he fell on it. Swore up and down he wasn’t making it up.”

My eyes go wide.

“It was a sixteen-ounce jar, but still. Men. They’re sick, I tell you.”

“The bats weren’t attacking me, per se. I think I was in their way.”

“I believe you,” she says. “I heard they found bats inside several homes in Arbor Ridge Ponds. I bet some deranged, bat-loving lunatic is behind the population climb, roosting them in his house, carving bat houses and setting them about his yard, fantasizing he’s going to become a vampire. Bats are supposed to be dying off, I thought. White-nose syndrome, my ass.”

I smile, and tension eases in my shoulders. Even though hospitals and their staff make my skin crawl, women like this make all of life’s problems manageable. I need to shrink this woman and put her in my purse so she can blurt amusing aphorisms throughout my day and depreciate my worries. Politicians and diapers should be changed often and for the same reasons!In forty years, thousands of old ladies will be running around with tattoos!

She continues, “People are crazy, I tell you. My neighbors, I’ve known these people ten years; I’ve shared an ungodly number of wine bottles with these people, as you do with neighbors. Last month my neighbor lets it slip they’re into suspension.” She smacks my arm flab again. “Like, suspending from their body piercings.” She’s shaking her head. “This couple, they’re in their fifties. You think you know your neighbors, but you don’t.”

My stomach clenches. Inside thirty seconds, I come up with four unlikely but possible scenarios resulting in one of my sleeping children dying, and I have a fifth idea in the works.

I want out of here. I hoist my purse into my lap and reach inside for my cell phone, overwhelmed by an urge to check on Valerie and the kids.

4

THE SKIN PEELED BACK

The kids are sleeping, same as when I left.

Of course they are. Why would you expect otherwise?

After Valerie leaves, I stand over Chloe’s bed and listen to her breathe. She’s on her front with her knees tucked under her chest, balled up like a baby, and I match my breathing to the rise and fall of her small, curved back. I hover too long, waiting for her rhythmic breathing to falter, waiting to catch her case of sudden unexplained death in childhood, SIDS’s ugly cousin. I reluctantly retreat and peek in Wyatt’s room. The pale bottom of his big foot, soft and flawless, sticks off the end of his loft bed. I want to kiss it.

Healthy and safe, I tell myself in the voice of a seasoned cop who is trying to calm a frantic parent. I head into my room, grab my laptop, and climb into bed.

It’s going to be another restless night. My pulse is acute, and my worries are rolling downhill like a cartoon snowball, gaining bulk and urgency.

I open my laptop and search Leland Ernest. Nothing comes up. Well, three obituaries pop up, but those are unrelated to my neighbor, obviously. My neighbor has no online presence. No Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn. No school history, work history, or reported arrest. I’ve searched online the past few nights, hoping the Kilkenny police will report on suspects, hoping someone will mention my neighbor.

My neighbor.

When you buy a house, you have a pre-made list of questions—How long is the commute? How much you will have to spend on repairs? How old is the roof? Has there been mold? How much traffic is there on the street out front? How many showers? Does the house emanate a pleasant feng shui vibe?—but the huge question mark, the major unknown, the one thing you absolutely can’t control or fully investigate is your neighbors.

To each of your days, they can add sudden, unexpected joy or debilitating terror. They can provide an onion in a pinch or they can steal your sense of freedom. Since I moved into this house months ago, I’ve only talked to five or six people on my street. Creepy Leland and Scary Lou are two of them. While I managed to nab a house with two bathtubs, my neighbors suck.

It’s been five days since I met Lou.

I’d been fetching Wyatt’s bicycle from down the street.

Wyatt’s chain had twitched off, and he’d fallen. He’d abandoned the bike and limped home with scrapes on his palms and knees like mashed strawberries.

Damn second-hand, third-rate bike.

I was stretching the bike chain back onto the chainring, my fingers and palms sticky with gear grease, grass pressing into my knees, when a man said, “Hey,” his tone loud and crotchety like he was going to let me have it.

Feeling at once bold and exhausted, I turned toward him. “Yeah?”

He wore slides over black socks pulled up high and a white T-shirt tucked into khaki shorts. His old man outfit clashed with his turquoise sweatband, which cinched his flyaway, graying hair. He must be a sweater. The hair above his sweatband lifted a little in the evening breeze. I didn’t peg him for an expressive guy who wanted a splash of color to mix things up. Had to be a penny-pincher who’d found a use for his wife’s decades-old sweatband. His hand was bandaged. I aged him around sixty so I assumed he’d had a biopsy of a suspicious mole.

His dog barked behind the screen door, everything dingy and shadowed inside the house. It was a husky mix of the lean, wolfish variety and sounded like it wanted to pick a fight. Hands on hips, the man said, “Your next-door neighbor is a suspect.”

Talk about going in rough and dry. This guy had no foreplay talk, and it took a moment to get my bearings. “Suspect of what?”

“You know, that Boone girl.”

I had been all too familiar with that Boone girl. I’d watched her YouTube video so many times, it was already playing out in my mind. Ava’s mischievous smile showcasing her missing front tooth, the flesh soft and swollen as fruit pulp where a new tooth was breaking the skin, her smooth baby face hinting at angular beauty, and her voice, unsettling in both its husky tone and nuanced maturity.

“Which neighbor?” I said, getting to my feet. The afternoon sun was too harsh. I was squinting, wishing I’d brought my sunglasses. The air was burnt and ashy, like someone’s dinner gone awry. “What did they do?”

“The guy to your right.” The old man had cold eyes; two black marbles squeezed tight. “He was flirting with her right before she went missing.”

I cringed. Flirting with a five-year-old? How was this man comfortable saying something so obscene without at least dimming his voice?

I knew the neighbor he was talking about. I’d helped Leland move a dresser up his stairs five or six weeks ago. My creep radar had been gonging, but I’d convinced myself I was being a snob.

“I wanted to tell you the day you moved in, but didn’t… well, I…” he bit the inside of his cheek, “I didn’t want to ruin your day. I’m Lou, by the way.” He nodded, but kept his hands on his hips. His dog’s barking, hoarse and snarly, persisted.

Oh. That’s why he’d started the conversation bluntly. Since the day I’d moved in, Lou had probably been biting the inside of his cheek, sweating into his sweatband, wanting to tell me about Leland Ernest, but didn’t want to ruin our move. Lou had shaken the can so many times, he couldn’t pull the tab slowly to let it fizz; it was bound to explode.

My irritation eased. As rude and peculiar as Lou seemed, I appreciated his directness. No one else had bothered to warn me about Leland.

He said, “I got a wife and daughter. My daughter, Rachel, she’s seventeen.” He sighed, and I couldn’t tell if he sighed because he was almost in the clear, his daughter had almost aged out of kidnapping, or if he felt more weighed down that she’d entered prime rape age.

“Nobody told me,” I said. I sounded weak and grouchy, which matched how I felt. I considered all the people who could have told me: my realtor, the guy who sold me the house, my neighbor Brooke, whom I’d actually met before I bought. She could have warned me. The word community formed in my mind, hard and jagged as shattered glass. Well, maybe they didn’t know. I picked up Wyatt’s bike and walked it to the sidewalk. “How do you know?” I said.

“Secretary at my work, her brother is a cop. Your neighbor Leland was hired to paint the Boone house, but he was, well, too friendly with the girl.” When I said nothing, Lou said, “I’m a screw mechanic.”

His husky’s bark was still loud, but too repetitive; it had lost its angry edge.

“Wait,” I said. “Wait. He was just being friendly? That’s it?” Raising a boy brought out the defender in me. Wyatt was friendly. I didn’t like the idea that he might be suspected of wrongdoing for being simultaneously friendly and male.

Lou worked his jaw, then inhaled so big his chest puffed. His nipples hardened under his thin T-shirt. “He followed my girl while she walked home from the bus stop. Drove his car behind her, asked her if she wanted to go bowling at the mall.” The way he said it, “mall” sounded vulgar. “This was when she was thirteen.”

My stomach twisted. “What did you do?”

“I don’t have money to hire a lawyer, and I know how these things eat up tons of money and never go nowhere.” I believed him. The divorce was still a bitter pill in the back of my throat, tasting of dollar bills marinated in filthy fingers.

It looked like money was tight for Lou. His roof was rotting, his driveway was ridden with potholes, and he had no landscaping, not a single bush. “What we did was, we got a dog, and my wife drove Rachel home instead of her walking.” He bit the inside of his cheek, considered something, then said, “I rang Leland’s doorbell and told him, if he talked to my daughter again, I’d slit his throat.”

I pictured flesh opening, blood oozing from its center. Goosebumps lit the back of my arms. Chilling. It was chilling that he said that. I wanted to get away from this shark-eyed man, yet it was like I was looking into a mirror. His protectiveness was fierce, borderline repulsive.

“Well, so, that’s what we did,” he said quietly, almost to himself. He brushed his sandal against something in the grass, schoolboy shy, regretting the throat-slitting admission.

“Do my other neighbors know?”

“I told the ones who have kids.”

Assholes.

I started home, trying to keep my greasy fingers splayed and away from Wyatt’s handlebars. The teeth edging Wyatt’s bike pedal tripped my shin, and the biting pain brought my attention forward. The pedal left me with four horizontal indentations, the skin peeled back, a dot of blood welling in each hole.

“Looks like you got yourself a piss-poor bike chain,” Lou said.

“Yes, that I have.” I tried to laugh, but my laugh dribbled. “I’m Grace, by the way,” I said, walking quickly away, panic suddenly on me, harassing me like yappy pooches nipping at my heels, pawing at my shins.

That panic, it’s still there. It hasn’t eased, hasn’t quieted, since I talked to Lou.

Now my fingers glide over the small scabs on my shin and I wonder about Lou. I imagine an old shark, skin cadaverous, wearing a turquoise headband. I picture his jaw working, the mystery bandage on his hand.

I have never seen Lou’s wife or daughter, never. Maybe Lou was diverting attention away from himself for a reason. And maybe the thing between Leland and Lou’s thirteen-year-old was a misunderstanding. Thirteen is an age where fantasy and confused reality collide, like the extraordinary border where saltwater and freshwater meet, yet stay separate.

Maybe, but I doubt it.

I spend another hour on my laptop before I open Ava’s YouTube video, what I consider to be the finale of my websurfing. Ava is the last thing I will see before I close my eyes. Ava is one last potato chip in my ritual of greasy worry-gorging until my stomach feels queasy and bloated.

Every time I pull up her video, I expect it to have been removed, taken down from YouTube for violating some law related to an ongoing crime investigation. A few days ago, I recorded the video on my phone in case this very thing happens.

But no, her video is still here. The family posted this one minute and nineteen second video of their daughter weeks before she went missing, and now the video has over four million views. If her parents posted with aspirations for Ava’s fame, I bet they regret it.

5

A GAME OF HEDGE-CLIPPER TAG

Wyatt, Chloe, and I are outside on the back deck by 9:00am. They are eating from their bowls; I am drinking tea. Morning sun is low and glorious, and a comfortable September breeze twirls the wind spinner we hung in a small crabapple tree. On mornings like these when the kids are outside, sitting still, listening to birds and observing neurotic squirrels jump from tree to tree, I try to toss my mental garbage out to the curb. All my worries, all my bad decisions.

Moments like these—when I get to watch Chloe’s gossamer eyelashes lower and lift as she gazes up into the tree, when I get to witness Wyatt smile at his little sister as if no one is watching him enjoy her—are bliss.

My neighbor will be deemed harmless, but will still move away.

I will not die of rabies.

The children won’t feel abandoned or unloved or guilty because I divorced their father.

I will win a small amount of money, which will allow me to dig myself out of debt.

I will get this yard under control.

I can fix broken things in a house.

I will catch that nasty chin hair the very morning it sprouts.

“Mom,” Wyatt says, gazing up, “you know how birds fly in a V?”

“Yeah.”

“How do you think they decide who’s the leader?”

“No idea, Wy. Let’s look it up during Chloe’s nap.”

“I’m all done with naps,” Chloe says, pissed off.

“That’s nice,” I say. “Who wants to swing?”

Everybody’s a sucker for the swing set. Ours is two swings and a slide framed by wood that is splintering and stained moss-green, but still sturdy. Chloe swings on my lap, then Wyatt’s lap, then she swings solo on her tummy, her downy, white-blond hair puffing and hanging mid-air before her body pulls it the opposite direction.

We pick wild raspberries off prickly brambles behind the shed and pop them into our mouths without worrying about dirt or microscopic worms.

Don’t look at his house. Not a single glance.

The kids migrate to the sun-faded, hole-ridden sandbox under the slide, and I discreetly slip away to unlock the shed. It is a circular combination lock, and the motion of my fingers rotating past the numbers brings back an angst associated with the memory of rushing my high-school locker open.

The heat and odors pouring out are both suffocating and nostalgic. Hot grass, thick oil, and decay. There is a faint buzzing in the dark, cluttered back corner. I imagine a small cluster of carpenter bees working on a home. They haven’t bothered me yet, and the kids don’t go in the shed because it’s always locked. Coaxing bees to relocate is a concern for another day.

I grab hedge clippers, gardening gloves, a big shovel for me or Wyatt, and a plastic hand trowel in case Chloe insists on helping.

I hack weeds that have grown too solid, too tree-like to pull. My shiny clippers gnaw at their thin trunks. Mosquitoes aren’t too bad, but the heat and humidity are relentless. Plus, I’m wearing a turtleneck; I didn’t want the kids to come in contact with my scratches.

I peek at the kids every few minutes. Still in the sandbox. Wyatt still patient even though his sister ruins every damn thing he builds. Nevertheless, his bucket of patience is small and will soon be empty.

My yard-work timer is short. I have fifteen minutes, tops.

I swear I weeded here a week ago. Look away, and things spiral out of control. Gnats buzz the corners of my eyes.

Inside the house, the landline rings.

I feel obliged to answer the landline because the answering machine is set too loud and I hate hearing my recorded voice at such an irritating volume. I have been meaning to change the volume on that thing since we moved in. I glance at the kids, drop the clippers in the grass, and peel off my gloves.

Inside, air-conditioned coolness blasts my skin and feels amazing, like a cold beer slipping down my throat felt a decade ago. “Hello?”

“Hi, Grace. This is Chuck. Sorry I didn’t get back to you yesterday. I’m catching up on phone calls this morning from home.”

At the sound of his voice, my skin prickles and my throat quivers.

Chuck is the representative for Whisper County State’s Attorney’s Office. We have become strangely familiar these past five days. During our previous two conversations, I drilled him with questions about Ava Boone’s case, driving my raw emotion across telephone wires.

He has not enjoyed talking to me. I am a mosquito buzzing his ear, but he empathizes and that’s why he hasn’t blown me off. I haven’t asked him, but I’m guessing he has kids. He is also Liz’s neighbor. He knows I work with Liz so it’s just as possible that he doesn’t have kids, but doesn’t want to be a dick to his neighbor’s pesky friend.

I stand at the screen, watching the kids. Still in the sandbox, still getting along. A small lottery.

“I’m sorry to keep bugging you,” I say, not sorry at all, “but I need more details about Ava’s case.” It’s difficult to even say her name. It feels indulgent or shameful or careless or maybe all of these.

Don’t consider what she’s like, that she’s a girl with an easy joy in her eyes, generous with her candy, mortified of bees, and will stand her ground when it comes to brussels sprouts and hairbrushes. That she has a bad habit of picking at the dry edges of scabs on her knees. That she dances and twirls even when there’s no music. That she loves cats and horses and anything you can sniff: markers, lip gloss, lotions. Don’t dare contemplatewhat she might have gone through. What she might still be going through.

“Well,” I say, “not about the case, but why Leland Ernest is a suspect.”

“Listen, Grace. Like I said before, my hands are tied in what I can tell you because the investigation is ongoing.”

We have gone through boring, rehearsed generalities before. I need more. I need gossipy details that will give me a feel for my neighbor’s state of mind and why the police consider him possibly dangerous.

Don’t let him off the phone until you get at least one detail.

“Chuck, I need to gauge how dangerous this guy is. I mean, my kids are outside. They’re in the sandbox right now. Should I let them outside?”

He ignores this question. Of course he does. He maneuvered around most of my questions during our previous conversations, maneuvered himself off the phone, which is why I left him another message, which is why we are talking again.

“If the detectives had evidence that Leland abducted a child, they would have charged him,” he says. “But there is no case against him. Ava Boone is, well, it’s not a court case; it is a police investigation. All I know has come from talk around the office. The police department is your best bet for information.”

“I have called the police department. Many times. They won’t tell me anything.” He knows this.

I check the sandbox. Two heads? Affirmative.

“Chuck, I have a little girl outside. I don’t have a fence. My door is, I don’t know, twenty, thirty feet from his, nothing between our doors but grass and trees.” I gaze at Leland’s backyard. There’s a cluster of saplings at the end of his lawn, his own little forest. “If Leland is, was, a suspect, doesn’t that mean there is some concerning evidence on him?”

This is another question that will get a vague answer, but I need to keep the conversation rolling. I need to wear him out, I need him to feel bad for shutting me down over and over. I need to nudge him into an emotionally charged state of mind where his sympathy outweighs routine and protocol.

“Someone can be considered a suspect without physical evidence. If they had a motive or opportunity.” His coolness raises my pulse. My forehead feels tight.

“So, they have nothing on him? Leland is this innocent guy, and his neighbor, me, is going out of her mind for no reason?”

“That could be the case.” He sighs. Condescending.

The next time you call, he’s not going to call you back.

The helplessness I feel ignites my nerve endings, and sparks sizzle and race across bundles of neurons heading for my brainstem.

“Huh. I just realized something,” I say, my voice clipped and cynical. “You don’t know anything about this case. Not a thing. Detectives haven’t shared information with you. The guy down my street knows more than you. He said Leland was flirting with her.” I shove the word flirting off my tongue like Lou did, head high, shoulders back, but inside I’m quivering. “Why didn’t you just tell me straight you knew nothing? Why waste your time, my time?”

I cringe at my poor manners and cruel accusations, and hold my breath. I am crossing my fingers that he’s embarrassed for me and he won’t mention to Liz that her friend is a douche.

He sighs again. Not condescending, but annoyed. “Off the record. This is off the record. Ava’s dad told detectives Leland took an interest in the girl. They hired him to paint interior walls, the kitchen and bathrooms, I think. He was there, painting, for a week and he talked to Ava a bunch of times. He was trying to teach her to whistle.”

My breath catches. His casual tone is like steel wool rubbing against my tender eardrum. He was trying to teach her to whistle. It sounds innocent, yet it sounds lewd. I gnaw at wet, rubbery skin along my thumb, biting tiny pieces off, willing myself to not interrupt.

“He asked her what she wanted for her birthday. Asked her what color her room was painted. One day he gave her a Happy Meal toy. A Shopkin character.”

Chuck definitely has a kid. No other reason to know about Shopkins: plastic, thumb-size figures which personify food items or accessories. A happy, wide-eyed root beer float. A winking, long-eyelashed ice cream sundae. A coquettish handbag. Chloe has about thirty of them.

“Ava’s dad let her keep the toy, but he didn’t like the gesture. She goes missing a week later,” Chuck says. “They interviewed Leland once and didn’t get anywhere. That is all I heard.”

Dang, Chuck. You didn’t even make me work that hard.

Maybe because it’s the weekend and he’s working from home. Maybe he’s barefoot, sitting on his deck, sipping coffee. Maybe he’s in his boxer shorts. Maybe he’s hungover. But I’m pretty sure it’s because I called him an out-of-the-loop loser, and it got to him.

I open my mouth, ready to probe into what else Ava’s dad might have told detectives, but I glance at the sandbox.

Empty.

Wyatt is on the swing, gazing into the tree canopy. The other swing is bare.