13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

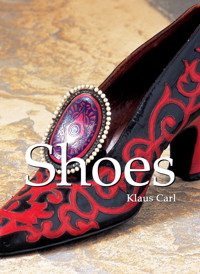

Mega Square Shoes focuses on the history of the shoe and elevates the shoe to the rank of a work of art. The author is a leading expert on the subject and curator of France‘s Shoe Museum, which holds the greatest shoe collection in the world, with 12,000 specimens.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 58

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Klaus Carl

© 2023, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2023, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© 2023, Joël Garnier

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-948-4

Contents

Shoe designers:

André Perugia

Salvatore Ferragamo

Andrea Pfister

Pietro Yantorny

Roger Vivier

Julienne

Sarkis Der Balian

Raymond Massaro

François Villon

Robert Clergerie

Alessandro Berluti

John Lobb

Patrick Cox

Glossary

List of Illustrations

Foreword

“You never truly know someone until you have walked a mile in his shoes.”

Aside from noticing a shoe for its comfort or elegance, contemporaries rarely take interest in this necessary object of daily life. However, the shoe is considerable in the history of civilisation and art.

In losing contact with nature, we have lost sight of the shoe’s profound significance. In recapturing this contact, in particular through sports, we begin its rediscovery.

Shoes for skiing, hiking, hunting, football, tennis or horse-riding are carefully chosen, indispensable tools as well as revealing signs of occupation or taste.

In previous centuries, when people depended more on the climate, vegetation, and condition of the soil, while most jobs involved physical labour, the shoe held an importance for everyone which today it holds for very few.

We do not wear the same shoes in snow as in the tropics, in the forest as in the steppe, in the swamps as in the mountains, or when working, hunting, or fishing. For this reason, shoes give precious indications of habitats and modes of life. In strongly hierarchical societies, organised by castes or orders, clothing was determinant.

Princesses, bourgeoisie, soldiers, clergy, and servants were differentiated by what they wore. The shoe revealed, less spectacularly than the hat, but in a more demanding way, the respective brilliance of civilisations, unveiling the social classes and the subtlety of the race; a sign of recognition, just as the ring slips only on to the most slender finger, the “glass slipper” will not fit but the most delicate of beauties.

The shoe transmits its message to us by the customs which impose and condition it. It teaches us of the deformations that were forced on the feet of Chinese women and shows us how in India, by conserving the unusual boots, the nomadic horsemen of the North attained their sovereignty over the Indian continent; we learn that ice-skates evoke the Hammans while babouches suggest the Islamic interdiction to enter holy places with covered feet.

Sometimes the shoe is symbolic, evoked in ritual or tied to a crucial moment of existence. One tells of the purpose high-heels served: to make the woman taller on her wedding night in order to remind her that it is the only moment when she will dominate her husband.

Wooden sandal inlaid with gold. Treasure of Tutankhamun 18th Dynasty

Thebes The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo

Egyptian sandals. Made from plant fibers

Bally Museum, Schönenwerd, Switzerland

Sandals. Found in the fortress of Masada

Israel

Iron shoe. Syria, 800 BCE

Bally Schuhmuseum, Schönenwerd, Switzerland

Silver sandal. Byzantine period

Bally Schuhmuseum, Schönenwerd, Switzerland

Men’s slipper. Vamp decorated with motifs gilded with gold leaf, Egypt

Coptic era Musée International de la Chaussure, Romans

The boots of the Shaman were decorated with animal skins and bones in order to emulate the stag; as the stag, he could run in the world of spirits.

We are what we wear, so if to ascend to a higher life it is necessary to ornate the head, if it becomes an issue of ease of movement, it is the feet that are suited for adornment. Athena had shoes of gold, for Hermes, it was heels. Perseus, in search of flight, went to the nymphs to find winged sandals.

Tales respond to mythology. The seven-league boots, which enlarged or shrank to fit the ogre or Tom Thumb, allowed them both to run across the universe. “You have only to make me a pair of boots,” said Puss in Boots to his master, “and you will see that you are not so badly dealt as you believe.”

Does the shoe therefore serve to transcend the foot, often considered as the most modest and least favoured part of the human body? Occasionally, without a doubt, but not always. The barefoot is not always deprived of the sacred and, thus, can communicate this to the shoe. Those who supplicate or venerate the shoe are constantly throwing themselves at the feet of men; it is the feet of men who leave a trace on humid or dusty ground, often the only witness to their passage.

A specific accessory, the shoe can sometimes serve to represent he who has worn it, who has disappeared, of whom we do not dare to retrace the traits; the most characteristic example is offered by primitive Buddhism evoking the image of its founder by a seat or by a footprint.

Made of the most diverse materials, from leather to wood, from fabric to straw, or whether naked or ornamented, the shoe, by its form and decoration, becomes an object of art. If the form is sometimes more functional than aesthetic, the design of the cloth, the embroidery, the incrustations, the choice of colours, always closely reveal the artistic characteristics of their native country.

The essential interest comes from that which it is not; weapons or musical instruments are reserved for a caste or a determined social group, carpets are the products of only one or two civilisations, it does not stand up as a “sumptuous” object of the rich classes or a folkloric object of the poor.

The shoe has been used from the bottom to the top of the social ladder, by all the individuals of any given group, from group to group, by the entire world.

It seems that man has always instinctively covered his feet to get about, although there remains no concrete evidence of the shoes themselves.

Prehistoric shoes would have been rough in design and certainly utilitarian in function. The materials were chosen primarily for their ability to shield the feet from severe conditions. It was only in Antiquity that the shoe would acquire an aesthetic and decorative dimension, becoming a true indicator of social status.

Liturgical shoe. Plain embroidered samite, silk and gold thread. Spain, 12th century

Musée des Tissus et des Arts, Lyon

Poulaine-style shoe

Bally Schuhmuseum. Schönenwerd, Switzerland

Poulaine

Bally Schuhmuseum. Schönenwerd, Switzerland

Men’s shoe. Black distressed leather, upturned pointed toe, studded sole, claw heel, Persia, 15th-16th century

Musée International de la Chaussure, Romans

Chopine. Venice, 16th century

Musée International de la Chaussure, Romans

Ladies shoe. France, Henri III period, 16th century

Musée International de la Chaussure, Romans

From the first great civilisations flourishing in Mesopotamia and Egypt in the 4th