Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

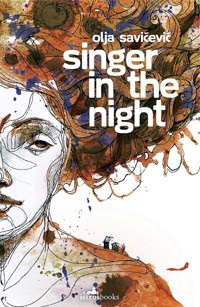

Famous soap opera scriptwriter, Naranča, is slowly losing her memory and decides to embark on a road trip down memory lane (in a golden convertible) in search of her greatest love and ex-husband, an artist whose uncompromising artistic integrity is opposed to Naranča's fickle life in the world of TV drama. It is the memory of a series of letters written over several weeks and hand-delivered to the inhabitants of the street where they lived, that cracks open the novel. The letters, triggered by a mysterious couple who make love loudly for hours in the middle of the night, keeping the neighbourhood awake, touch upon the nature of love, war, lust, nationalism, capitalism, and childhood, highlighting the paradox of the human condition through playful humour. Singer in the Night is a rich, sensual novel which comments on communal perception, on how life is really lived. In its final message, the novel gives a playful warning about the consequences of choosing banality over true human connection.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 223

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SINGER IN THE NIGHT

Olja Savičević

Translated from the Croatian by Celia Hawkesworth

First published in 2019 by

Istros Books

London, United Kingdom www.istrosbooks.com

Copyright © Olja Savičević, 2019

First published as Pjevač u noći in 2016

The right of Olja Savičević, to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Translation © Celia Hawkesworth, 2019

Typesetting: Davor Pukljak, www.frontispis.hr

ISBN

Print: 978-1-912545-97-1

MOBI: 978-1-912545-15-5

ePub: 978-1-912545-20-9

This publication is made possible by the Croatian Ministry of Culture.

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s “PEN Translates” programme, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

Part One

LETTERS TO LOUD LOVERS

‘Here at last is a true lover,’ said the Nightingale. ‘Night after night have I sung of him, though I knew him not: night after night have I told his story …’

Welcoming letter

Dear citizens, householders, close friends, fellow townsfolk, mild and attentive civil servants and waiters, courageous and patient nurses, magicians’ secretaries, dressers of abundant hair, eternal children in short trousers, seasonal ice-cream sellers, dealers in intoxicating substances, drivers who brake on bends, gondoliers of urban orbits, captains on foreign ships, foreign girls on captains, neighbours – agreeable disco gladiators, neighbouring proto-astronauts and everyone else in Dinko Šimunović Street, not to list you all,

I am writing because before I leave I want to tell all of you that we live in the loveliest street, in a wonderful city, in a country without match or peer!

The sun rises at five, warms us, and sets at eight, sometimes at nine, and at night, without our knowing it, cascades of meteors pour over our heads, while down below, in front of our doorways gleam the little golden stars of apartment bells, caper flowers close their calyxes filled with heady aroma, and the quiet air refreshed by nocturnal moisture is riven only by lovers’ cries. Summer in the city is rainy and hot and plants from ground-floor gardens beside the root and trunk of skyscrapers grow as far as the birds, up to the tenth or fourteenth floor. Some may find that monstrous, but it’s beautiful. Towards evening, cats awaken, and go scampering along the branches of the climbing plants, they fly over the narrow sky-filled gaps between apartments, with the occasional curse flying after them, which makes the image real and protects us, up to a point, from madness.

It may be like this also in other towns on the meridian and further afield, but do they have such tall and proud men, modest champions with powerful thighs and such well-built women with ponytails and long nails, somewhat impudent, in the way that a thorn on a rose or bramble by the road is impudent, do they have such aromatic pines constantly under their city windows, such melodious voices, such healing sea and such a street, a cheerful torrent, a musical ladder, a flight of steps travelling into future memories, into incorruptible childhood? And are they aware of it?

Because, if you do not know how lucky you are, then you really are out of luck. Enjoy it all, even unthinkingly!

With love from your neighbour,

Nightingale,

35 Dinko Šimunović Street.

Two weeks had passed since that event, and I had set out in search of the man who wrote the letter. After a brief visit to Split, I decided to turn off the motorway onto a side road and to speed off into that steppe-like landscape where even a goat would go hungry, towards his native village.

Even then I was aware that I was finding it increasingly hard to concentrate and that my thoughts were slipping away. I could not recall the meaning of a road sign: a consequence of my state of mind, or perhaps ordinary emotional excitement. (Maybe both). That’s why I’m going to record them – those thoughts and letters – so that my notes about everything that was happening or was going to happen in connection with all this would remain preserved for me (primarily for me, yes) and maybe for someone else, my dear.

Mitrovići, Nightingale’s village, in the hills where the frontiers of Croatia meet Bosnia and Montenegro, has a small U for the Croatian Ustasha and a sticker of the Hajduk football club logo stuck beside the name of the village, above the name is a stop sign – you have to stop (although there’s never anyone there) before continuing on your way.

His mother met me in front of the bell-tower plonked in the middle of the village. The clock on the tower, black hands on stone, was fifteen minutes late and pointed to midday. She was alone, she and several flies, and she had not sat down but, large and round as she was, she was rocking from one foot to the other. She had wrapped a black scarf with bright pink roses on it round her head: her face blossomed into a smile when she caught sight of me. The beginning of September is hot, but not in that lethal July way. September is summer after ecstasy, lazy, stupefying and discreetly illuminated in the moment before everything that has just ripened begins to rot. Everything has been brought to its height, in tastes and colours, and then subdued into an over-rich tenderness, melancholy.

She said ‘Bloody ‘ell you looks great, better than on telly!’

She said that and kissed me on both cheeks, then took my arm and led me into the house on the square.

I looked dreadful, after two days’ driving with a broken air-conditioner (the fact that the car is a convertible didn’t help) and after I’d been peed on by a dog, but I didn’t say so, after all that I was glad of that moment, that compliment.

‘Nothing from Gale,’ I say, taking out his last letter. ‘I was given this by the lad who’s looking after his flat, living there. (I didn’t mention the other letters.)

She took a carob pod out of her apron pocket and chewed it. Then offered me another. ‘More scribbling, damn ‘is eyes. I can’t read it any more. So tell me – no one knows where he is. What do we do now? How’re you going to find him? And what if he’s not in Bosnia? You’d do better not to look for him.’

She’s called Josipa, Nightingale’s Mum.

She flapped her hands over her thighs a few times – I shrugged my shoulders. ‘Don’t worry, my dear,’ I say. ‘I’ll find him. The world is limited, but time is infinite.’

She looked at me quizzically as though I had spoken in Chinese and swatted something with her hand.

‘It’s a quote from a graffito, my dear. Gale wrote it,’ I say. I didn’t want her to think I was making fun of her. I felt stupid and in my awkwardness I downed in one gulp the brandy she had poured for me.

She put her hand out towards the letter. ‘So, let’s have a look!’

She read slowly, her lower lip forming the letters.

‘He had put it in all his neighbours’ letterboxes before he went away, instead of saying goodbye I suppose.’

‘It always surprises me, what he writes. But I can’t make anything of this. Is he sick, what do you think?’

I shook my head.

‘I’m glad he’s okay. Since when does he love Split?’

‘Sorry?’

‘In the letter he loves Split. He didn’t like it much before, he didn’t even go out, except at night like a fool.’

She squinted at me and the roses on her head shook.

‘He was never completely normal, ever since my late husband gave him the name Nightingale, I would have called him Daniel or Petar. We were old when he came along, maybe that’s why he’s like he is. It’s shameful in the village, me having a child at forty-two and my man a whole sixty years old. Our neighbours were getting grandchildren, and we had a baby. But to hell with the village, bugger the village and the whole district. But I won’t say a word, I’ll shut up,’ – here she started to laugh – ‘because the way his daddy used to chirp at him like a bird, he could have been a peacock or a swan.’

She wiped her nose on a kitchen cloth and poured us both another glass.

‘My parents had my brother when they were in their forties too, so what?’ I say ‘He’s more normal than many others, my dear, Gale is. Nightingale is a real artist, that thing with the letters to his neighbours, that’s in fact a great performance.’ I wanted to say something consoling. ‘Besides, Gale and I are similar, nonsensical, a bad lot here. Each to his own.’

‘You’re an artist, for sure, how come he is? He scribbles on walls, upsets people. The police are after him.’ She chomped on her carob, which must have been too hard, because she spat it out into the sink. ‘If he’s so clever, why’s he skint?’

She was angry, her cheeks flushed.

‘Is there a performance where he doesn’t get in touch with his mother for a year and more? Or makes a child he doesn’t even know exists for two years,’ she adds.

‘That’s bit radical.’ (Does Gale have a child?)

‘Radical, radical.’ She agreed.

Then she changed the subject; she ran through the TV programmes and politics and made us supper after which I kicked off my high heels, washed in completely cold water, because there was no hot water in the boiler, and quickly fell asleep in Gale’s childhood bed in the white room.

Beside the pillow, on a little table, lay a mouth organ, polished, cheerful, and beside the bed was a pair of school slippers, size 10. I had never seen such enormous school slippers, a child’s object. Josipa had left them out for me, but they were several sizes too big. There were a few school readers on the shelves, in the drawers neatly folded clothes belonging to some former child who would never return. The boat’s log-book, which I am looking for, is almost certainly not there, the old lady would have found it already. They never got on, the controversial Nightingale and his old mother.

Above the bed hung a tapestry of the Mona Lisa, which had once been sewn long ago by the young Josipa. The village women thought it was the Holy Virgin, she told me, smiling, ‘let them think so, let them, bugger me if I care what they think!’

For years afterwards the embroidered Mona Lisa became an important figure in Gale’s stories, sonnets, sketches and strip-cartoons. In the room, it rests calmly in the whiteness of the empty walls behind glass in an ornate plaster frame, sometimes friendly and gentle, but sometimes capricious and caustic, the Gioconda pricked out 13,190 times with a needle.

‘I don’t get that, what’s the point of these tapestries, who dreamed them up, what a scandalous waste of time. Is it obtuse or Zen? That’s crap, it’s really like my work. Except – I do it for money.’

That thought used to warm me like hot sun, but with time, with time it has cooled down a lot. But, hey, let’s get back to the story.

Around seven in the morning, we opened, then closed, the house door. I set off towards the car, accompanied by Josipa. She had a new headscarf, yellow, with blue peonies, non-existent in nature, but nevertheless peonies, wonderful peonies.

‘You’re dead set on finding him … Watch out for the mujahideen!’

I started the car.

‘Why them?’

‘They were on the News yesterday.’

‘Don’t believe the News, my dear.’

Perhaps it isn’t fair to tell an old person not to believe the News, that might freak them out, I thought. But still, I probably don’t have much clue about old people, my parents aren’t alive (my Ma died three years ago, darling). I remembered them beautiful, in their prime – they didn’t have a chance to get on my nerves. A friend of mine said that old people have selective deafness and they only take in what they want or can bear to hear.

Josipa shouted: ‘I’m only joking, I’m joking!’

I felt better, although I would not have sworn blind that she really was joking. I didn’t want to think of Josipa as a bigoted old hag, it’s hard to love people, they often mess things up. It would be nicer if dear, kind people weren’t chauvinistic idiots, but they are. I got out of the car quickly and hugged her, tight. ‘We’ll be in touch!’

I see her in my head (I do see her, now, clearly). A tall old lady, the tallest among the babushkas. The mother of my former seasonal bridegroom – the unrecovered-from Nightingale – is waving to me with both hands. It’s an Indian summer and in that pose she could be a mascot for it. Above her flowery head goldfinches flitted into the empty, pale early-morning sky, and the clock on the old bell-tower, the one I already mentioned, was still showing three in the afternoon.

I set off towards the border, towards Bosnia. The road swallowed me sullenly.

All right, I’ll tell you. So, my name is Clementine. On the outside, I’m a blonde orange. I have silicon lips, I have a Brazilian hairstyle, I drive a two-seater Mazda MX-5 convertible, gold, but inside I’m a black orange. Full of black juice.

The day before my meeting with Nightingale’s mother, the meeting with which I began this story, I travelled from Ljubljana to Split. I decided to make the journey after I had spent the whole of the preceding week vainly calling Gale every day. When I tried to pay money for the boat’s berth I discovered that his account had been closed months before, at the marina they told me he had paid all his bills, but, they’d noticed that for some time no one had been coming to the boat. His mobile was dead and at first that annoyed me, then it worried me (we had not been in touch often, in fact very rarely in recent years, and then mainly in connection with our shared boat, but nevertheless).

Then I began calling his family, our common acquaintances, our former neighbours: a whole lost life so unconnected with my present life that it could have been anyone’s, and that whole mini-Atlantis rose to the surface, my dear. None of the people Gale and I had known could say exactly in which direction that sexy bird had flown off last summer. They weren’t troubled, not even his mother to whom he had simply mentioned that he had something to do in Bosnia, not even she was troubled, she just looked anxious for a moment, or so it seemed to me, because that crazy Gale came and went like that, no one ever knew when. What I found on the Internet turned out to be of most use: the blog he had written for a while had been dead for a long time, he had completely abandoned the virtual life which he had in any case found vulgar, but Google knew anyway – he had worked for a while in Libya, then in Chernobyl. Then a photograph appeared and was published on a foreign portal: a mural with Bosnia and his name written under it. And that was all.

Officially, he lived in our old street, Dinko Šimunović Street, on the tenth floor in the same building and flat in which I had spent some time with him, but, as I said, I knew nothing about the last years of his life, although in the depths of my heart he had remained my beloved. It’s not that other loves hadn’t come along, my dear, but in Gale’s case that had no bearing on my preference.

My encounter with Dinko Šimunović Street two weeks earlier had not been agreeable (had so many years really passed?). I stepped into the street cautiously and briskly, not looking around too much. It was a hot afternoon and the street was deserted, although little stars beside the intercom indicated that tourists had penetrated even into these concrete oases. Gale is right, it’s the loveliest street in Split, a serious street, not a little street, lovely little streets are something else, there are lots of them, but I like big streets. And I like tall buildings and skyscrapers. And I like the twentieth century more than the nineteenth or the seventh. I’m not sure about the twenty-first yet. I once lived here as a child, with my parents, but, after my father died, my mother and brother moved to a smaller town and sold our flat (every inaccessible dirty join, every hidden crack was mine), I moved just a few hundred metres east, to Gale’s place (Ma could never forgive me, poor Ma, I left her so easily).

I don’t know which was worse in my encounter with Šimunović Street: what had stayed the same or what had changed. I didn’t have the time or the will for such emotions, to stop and rethink. I hadn’t expected it to shake me up. It was like that situation when you rush out in your slippers to empty the rubbish and meet some shithead from your childhood who keeps you standing beside the dustbin for fifteen minutes and under his insistent gaze you grow visibly older and more decrepit, fatter. The street looked at me, it watched me patiently, from all directions. I had to look at it, in passing, to see where I was walking: skyscrapers, tall, slender buildings, the flight of steps, the sea. This was a return to the intimate, oh boy.

The things we have and know drain away and vanish, new ones cover them over like grass over a grave; the world of the inert is closest to death. If anyone thinks I’m mistaken, let them try to imagine a town without birds, insects or people, a town of inanimate things.

Or a hill without plants.

Or an old dance hall filled with the ghosts of dancers.

Or a house through which war has swirled, after which the blood has congealed and it has been aired of the stench of soldiers’ boots, the hot, sweaty grenades have cooled and lie in wait, put away in the bottom of a cupboard, tucked under bedding.

Or a snowy wasteland when the sun goes down behind a mountain.

Or a closed road.

A factory: machines and turbines without workers.

That is emptiness such as a real desert will never know, because for centuries nothing has inhabited it apart from eternity. It is not unusual for people to imagine the setting of paradise just like that. At that moment there is more death in a cup after the coffee has been drunk and the colour drained, than in the Sahara.

Gale (I’m always debating with him in my head) believed in technological progress in the spirit of socialism and used to say that at some stage soon, when people, all people, would be going on outings to the Moon, he would put on an exhibition there of all the things that are important, to everyone, or at least to him. There’s no atmosphere there, no oxidation, and so no death of the inert and objects we care about really will last forever or at least longer than us. He would reproduce the whole of our street. Of course, when you’re seventeen, it’s easy to fall in love with someone who wants to put on an exhibition on the Moon in order to save beautiful or important things from decay, although I was already aware then that if not everyone could go to Tito’s island of Brioni, they wouldn’t get to the Moon either.

And what’s left for death if you forget everything before it? Is there anything left to die? When things turn the wrong way round and oblivion precedes death instead of death oblivion? It’s presumably a defence mechanism if the body decays so rapidly after it’s emptied by oblivion.

Where were we? Oh yes, Šimunović Street. Proof that tall buildings and skyscrapers can be attractive, that third Split, Split 3, Trstenik, my borough. Proof that socialism can be beautiful, as Gale would say.

In the lift, opposite the door to the flat, I straightened my skirt and fixed my make-up. Without lipstick a woman is naked, my mother used to say and that habit of using make-up, which some people find stupid, but is definitely entertaining, has remained with me from my teens.

‘Stone ve crows. I mus’ be dreamin’,’ that’s what the man in his thirties who introduced himself as Joe Pironi said when he opened the door, with a smile. He was wearing Bermudas: between his thin hairy legs a Maltese (called Corto, wittily but really) peered and barked at me. The next thing I noticed about Pironi was his oversized shaved head and blue eyes with half-closed lids.

‘Is someone, like, makin’ a film?’ Here he paused and lit a cigarette. ‘I know, crap joke.’

I stood on the threshold genuinely afraid of the dog’s snarling little teeth and explained that I was looking for Gale. I said I hadn’t seen him in years, maybe ten, but I wanted to sell the boat, quickly, and I needed his agreement. The boat was in his name, my dear, but it was still my boat, my inheritance, although, it’s true, he had maintained it the whole time. I scowl when I lie, but no matter, Pironi wasn’t listening to me in any case.

He said: ‘Who’d ever fink, mate. You wouldn’ credit it! So it never crossed ‘is daft mind vat he knows you and you’d come for the keys of the boat. Yeah, the cunt knew you’d come. You and Gale, man and wife, good as. But ‘e’s not ‘ere, ol’ girl. He went off to look for someone he made a kid wiv two or free years ago. He may be in Bosnia – Livno or Tuzla – or Timbuctoo. If you ask me, it’s not worth lookin’. Better wait till ‘e gets in touch.’

The Malteser in Pironi’s arms was still barking. He put it down on a table and from a drawer took out cigarette papers, tobacco and grass. The little dog spun round in a circle and tried to get down. I didn’t have time to wait for him (Gale) to get in touch. There were no books on the shelves, not a single one, which meant he had no intention of coming back. But still, his strange writing outfit was dangling from a hanger on the door of the wardrobe as though he had left it there the previous day.

Pironi said: ‘Wan’ a puff? Since you’re ‘ere, we could spark up a bit? ‘S no fun solo. Homegrown, from Vis, not sprayed, sweet as honey.’

‘What the hell,’ I said, ‘it must be healthy, I’ll have a drag.’

We sprawled on the couch. Corto retreated under it and curled up between our shoes.

Pironi said: ‘Struth, ol’ girl, I wouldn’ con you for ve world, I’ve no clue where that waster’s buggered off to, maybe Travnik, maybe Bugojno. I’m just, like, looking after the flat. You know, a Croat, so’s it’s occupied, if you get my drift. Last summer, before he scarpered, he got up the nose of the whole neighbourhood, the police were after him, you wouldn’ believe it. Vat made him mad, he didn’t expect that kind of reaction to his letters. It’s unreal, you know, ‘e’s a dreamer. I told him – give it a rest, bro, forget those jerks, mind your own business.’

I said that, in actual fact, it was Gale’s business. ‘He’s an artist, my dear, he has to interact with his surroundings, he has to change them.’

‘You’re kidding me, yeah? I’m an artist too. You must’ve seen those graffiti: I’m hungry, give me what you can, in front of the door, above the intercom? Right, you saw it. I’m not pretentious like some vat puts on an act, I’m more interested in reality.’

I asked him whether he was a gay activist, because it looked to me like gay graffiti although it had a socio-economic base. He asked, of course, did I want to find out and laughed: ‘how did I know it didn’t mean give me salami in my sandwich, for instance?’

‘You’ve got a dirty little mind,’ he said, grinning.

He said, Pironi did, that Gale had nearly got him in the shit with those letters, and something else about some business with explosives placed in a Split bank, because on the wall people had found the same sentences as in one of Gale’s letters. ‘They had him in, for questioning, twice,’ said Pironi, ‘but they couldn’t pin anything on him, because the letters had been sent to the whole street, several hundred copies.’ (Magnificent, magnificent)

But nothing concrete about where I might find Gale.

Last summer, the June before last, somewhat more than a year ago, in Dinko Šimunović Street some unknown lovers had made love loudly until dawn, waking the sleeping populace, and it was a hot summer, with daytime temperatures of forty-two and airless nights and many wide open windows.

Judging by everything Joe Pironi told me, and he told me a lot, disjointedly, I gathered the following: the letters that Gale had zealously dropped into his neighbours’ mailboxes had upset the whole street. They upset the street more than the reason they were written, although that too had sent sparks flying. I was agreeably surprised by their lack of indifference, even if it was negative. I was used to people here reacting only to football, which made Gale think them limited and worthy of contempt, but I was more tolerant and practical, because these were the people we had grown up with, I would have felt oppressed to think negatively about them or to think about them at all. Compromise, always compromise, well, I had to live with people or die alone.

In June of last year in Dinko Šimunović Street, Gale worked by night, so Joe Pironi told me: a well-known foreign, American, magazine had commissioned a strip cartoon from him, which was important to him – I presume it still is important to him – and noise interfered with his concentration.

On the tenth evening he, Gale, not Pironi, felt a powerful moral obligation to ask the overly-loud lovers to be a bit quieter (I don’t really believe that). But since, according to Pironi, he didn’t know who the moaners were, he wrote to almost everyone, working his way systematically, scattering letters into their letterboxes, but the groaning continued for three whole weeks, maybe even longer, into the second week of July. The street has this unusual cascading architecture, narrow buildings with hundreds of windows, and if someone is making love by the south-facing windows, high under the clouds, it is no simple matter to determine the source. It lasted for three whole weeks, maybe even longer, into the second week of July. Then it stopped.

And before Nightingale completed his game with the letters, which he had evidently entered into with his whole comical, idiotic and wonderful soul, a meeting of the tenants’ councils of the buildings nearest to the sighing in Šimunović Street was called:

the letters were collected and handed over to the police:

the police didn’t really know what to do with the material,