Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Five childhood friends reunite, 20 years later, in their Chesapeake fishing town and are forced to confront their own dark past as well as the curse placed upon them in this paranormal horror masterpiece from the bestselling author of Come with Me. Maybe this is a ghost story… Andrew Larimer has left his past behind. Rising up the ranks in a New York law firm, and with a heavily pregnant wife, he is settling into a new life far from Kingsport, the town in which he grew up. But when he receives a late-night phone call from an old friend, he has no choice but to return home. Coming home means returning to his late father's house, which has seen better days. It means lying to his wife. But it also means reuniting with his friends: Eric, now the town's deputy sheriff; Dale, a real-estate mogul living in the shadow of a failed career; his childhood sweetheart Tig who never could escape town; and poor Meach, whose ravings about a curse upon the group have driven him to drugs and alcohol. Together, the five friends will have to confront the memories—and the horror—of a night, years ago, that changed everything for them. Because Andrew and his friends have a secret. A thing they have kept to themselves for twenty years. Something no one else should know. But the past is not dead, and Kingsport is a town with secrets of its own. One dark secret... One small-town horror...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

One

Two

Three

i

Four

Five

ii

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Part Two

Twelve

iii

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

iv

Part Three

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

v

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Part Four

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Acknowledgments

About the Author

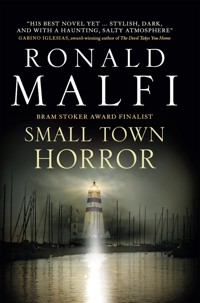

PRAISE FOR SMALL TOWN HORROR

“Malfi is horror’s Faulkner, and Small Town Horror might be his best novel yet. Stylish, dark, and with a haunting, salty atmosphere, this is a superb novel about how the ghosts of the past always dance with those of the present.”

Gabino Iglesias, Bram Stoker® and Shirley Jackson award-winning author of The Devil Takes You Home

“Small Town Horror blends the sunburnt southern noir of S.A. Cosby with the homespun haunts of Raymond Bradbury, creating a brackish blend of sin-ridden horror unlike anything else scuttling across bookshelves today. Ronald Malfi is the Bard of Chesapeake Bay gothic and the outright brine of this beautifully terrifying book will be steeped into your subconscious forever.”

Clay McLeod Chapman, author of What Kind of Mother and Ghost Eaters

“An eerie and deeply unsettling horror epic with faint shadows of Peter Straub and Robert R. McCammon flickering at the periphery . . . Small Town Horror is the kind of masterful and deftly written horror fiction that makes me fall in love with the genre all over again.”

Eric LaRocca, Bram Stoker Award® finalist, and author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

“This isn’t only Malfi’s masterpiece, it’s a heroic swing at the Great American Novel, and will be nakedly terrifying to anyone who’s been a kid—and to anyone who’s grown up with regret. This is heavyweight horror, a total knockout.”

Daniel Kraus, New York Times bestseller and author of Whalefall

“With strokes of King and shades of Jackson, Malfi burns bright in Small Town Horror.”

Lindy Ryan, Bram Stoker Award®-nominee and author of Cold Snap and Bless Your Heart

“Ronald Malfi is a gifted writer. You fear for his characters because they feel like people you know, ordinary people with dire secrets. Small Town Horror gives us broken people wrapped up in a past that won’t set them free, the kind of story Malfi has truly mastered. Nobody else can weave the kind of chilling, small-town horror story I grew up reading the way Malfi does. His writing is so strong and so of-the-moment that these horrors and fears tap into horror nostalgia while also feeling brand new. It’s some kind of magic trick, which makes Malfi one hell of a magician.”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling author of The House of Last Resort and Road of Bones

“Damaged characters, dark secrets, and traumatic histories swirl in this haunting and beautifully written tale of a grim past that refuses to stay buried. Ronald Malfi is fast becoming one of my favourite writers, and Small Town Horror cements his reputation as one of the best horror writers working today.”

Tim Lebbon, author of Among The Living

ALSO BY RONALD MALFI AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Come with Me

Black Mouth

Ghostwritten

They Lurk

The Narrows

ALSO BY RONALD MALFI

Bone White

The Night Parade

Little Girls

December Park

Floating Staircase

Cradle Lake

The Ascent

Snow

Shamrock Alley

Passenger

Via Dolorosa

The Nature of Monsters

The Fall of Never

The Space Between

NOVELLAS

Borealis

The Stranger

The Separation

Skullbelly

After the Fade

The Mourning House

A Shrill Keening

Mr. Cables

COLLECTIONS

We Should Have Left Well Enough Alone: Short Stories

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Small Town Horror

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781803365657

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803367583

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Ronald Malfi 2024

Ronald Malfi asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Thinking of Peter Straub …

… and of Rebecca: burn bright

“And his dark secret loveDoes thy life destroy.”

—WILLIAM BLAKE

“The past is never dead.It’s not even past.”

—WILLIAM FAULKNER

“Every love story is a ghost story.”

—DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

PROLOGUE

Maybe this is a ghost story.

If it is, then I am both the haunter and the haunted. Do I still hear the echo of that night, repeated forever, until it bursts across the firmament of space? Do I still sense all of those dark mementos nestled tight and unmovable in the blackened corners of my memory, stirring from time to time just to let me know they are never going away?

It was a sudden jolt, a disruption in the fabric of the universe, an unexpected divergence in the timeline of things. An accident. That one fateful incident has resonated in me with all the clamor of a star imploding, and no matter what I do—no matter what I’ve done—it never stops resounding. That steady war drum boom . . . boom . . . boom. I can’t move out from under it; I can’t escape it, no matter what I do to balance the good with the bad. No matter how many wrongs I try to right.

Listen: I’ll never stop looking at the palms of my hands, never stop studying the pallor of my flesh in mirrors as I pass by. I’ll never quit listening for the sloshing, liquid rattle in my lungs, or sniffing the air for the acrid stink of burning black powder whenever my eyes begin to sting and the tears spill down my heat-reddened face.

Tell me one of your stories?

No.

Not this one.

Never this one.

We were doomed from the beginning.

PART ONE

KINGSPORT . . .… AND THE WRAITH

ONE

Three months into Rebecca’s pregnancy, I began to worry that something terrible was going to happen to the baby. It didn’t hit me all at once, but rather it gradually insinuated itself inside of me: a seed taking hold in loose soil, casting its pale, sinuous roots to great distances. It started as a solitary notion, lighting upon me soft as a feather: what if something happens? It was a thought I was able to brush aside at first, but in the days and weeks that followed, it became a steady, worrisome drumbeat in my head: what if something terrible happens to the baby? Things like that happened all the time, didn’t they? Accidents, miscarriages, complications: a host of shadowed malignancies that caused in me inexorable concern.

As Rebecca’s pregnancy progressed, I found myself waking in the middle of the night from some disremembered nightmare, certain that there was no baby, that the pregnancy was actually the dream. I’d place a hand to my wife’s abdomen while she slept, the warmth of her body radiating through the thin fabric of her nightshirt, desperate to seek out confirmation that everything was as it should be. At work, I would sometimes be overcome with the certainty that Rebecca, wherever she was, had miscarried, and I would fumble my phone to my ear just to hear her voice. I told myself these were normal fears, that I was nervous about becoming a father, but that didn’t help quell my anxiety. My mind filled with innumerable baseless terrors—of stillbirths and nuchal cords and all manner of physiological defects. A dispossessed thing, large-eyed and staring, milky-blind, congealing in a forever soup inside my wife’s body. I envisioned a womb full of life one moment, vacant the next . . . as if a fetus was something as tenuous as a wish or a dream, and just as liable to disappear in the same fashion.

It was an irrational fear—there was nothing in Rebecca’s or my genetic makeup to suggest there’d be a problem, and by all accounts, the fetus was strong and healthy—yet by the end of that first trimester, I couldn’t shake the certainty that some dark wraith had arrived unbidden into our lives. That this thing had moved into our home, had latched onto us—or, more specifically, onto the baby—and would not go away.

I handled this the way I’d learned to handle most things in my life—I put on a false face and practiced the art of human mimicry. To keep my mind off my mounting unease about the baby, I plunged headfirst into work. This was nothing new to me—since my graduation from law school, I had always put my nose down and gotten it done—but I let work consume me, let it take all the time it wanted, and relished the evenings when I had to work late at the firm or bring reams of legal documents home to pore over deep into the night. The result of this extra time and energy got me high praise at Morrison and Hughes, the Manhattan law firm where I’d been working for the past five years. Desperate for distraction, I had sweated my way for months through a particularly daunting legal entanglement dealing with one of Bryce Morrison’s wealthiest (and shadiest) clients, Remmy Stein. The issue ultimately went before a judge, where my dedication to this client’s cause paid off; he and I left the courtroom that afternoon, sweat pooling in my armpits, an ear-to-ear grin on Stein’s ruby-red face. For my efforts, I received an engraved crystal award, thick as a phonebook, and a shiny new office on the fifth floor, where a wall of windows gazed dizzyingly through a maze of skyscrapers and office buildings downtown. Before I was fully moved in, I rested my sweaty forehead against the cool glass of one window and peered down. Below was a trash-strewn alleyway, cluttered with dumpsters and a blazing bit of brick-wall graffito that, quite ominously, proclaimed:

THE PAST IS NEVER DEAD

This, admittedly, did not help ease my state of mind.

* * *

Rebecca didn’t notice this change in me at first. She was still working, editing manuscripts from a pool of clients she had cultivated after leaving the publishing house where she’d worked previously, and was in overall high spirits. She looked perpetually radiant, with her curled copper hair swept behind her ears, and her green cat’s eyes alight. The freckles across the delicate saddle of her nose had become as pronounced as flecks of mica. It was like the baby was emitting some spectral light from inside her.

One morning I came out of the bedroom to find her sitting at the kitchen table eating raspberries from a small bowl, one of her client’s manuscripts on the table in front of her. She was in her robe, one bare leg tucked under her thigh, her hair shining in a slant of midday sun. I had spent too many hours at the office the night before, had gotten only a few scant moments of restless sleep, and so I staggered over to the coffee pot, took a mug down from the cupboard, and poured a full cup.

I sensed something in my wife. Her thoughts, moving about in that brilliant head of hers. I turned and looked at her—stared at her for several moments, in fact, unobserved. Losing myself for a time in that pale white tract of scalp where her coppery hair lay parted. The constellation of earrings along the perimeter of one ear caught the sunlight and momentarily blinded me.

“How’s the novel?”

“Oh,” she said, curling one corner of the manuscript page between her thumb and forefinger. “The author is obsessed with head hopping.”

“What’s that?”

“He’s telling the bulk of the novel in first person, then he jumps at random into some other character’s head in third person. It’s jarring.”

“Maybe there’s a reason for it in the end,” I said. I kept looking at my wife, sensing some disquiet moving around inside her, just beneath the surface.

“Hey,” she said, looking up at me. “Can we talk for a second?”

“Of course.”

I sat at the table. The manuscript in front of her looked as thick as a cake box. There were red pen marks on the top page where she’d been editing.

“Will you level with me?” she said.

“About what?”

“About what it is that’s been haunting you for most of this pregnancy.”

I set the coffee mug on the table. My wedding ring accidentally knocked against the handle, eliciting an eerie, discordant chime that seemed to hang in the air for much longer than it should have.

“It’s nothing, Bec. It’s just stress, worry, about to be a new father. All of that.”

She shook her head, so slowly that it was hardly perceptible. Her eyes, those perfect green jewels, glittered. “No.” Her voice was small but firm. “No, that’s not it. It’s something you’re keeping from me. I can tell. You’re not sleeping. You’re more restless than the baby. You kick. Also, you’ve been so . . . preoccupied.”

“Honey,” I said, and reached out to her.

She drew away, just as slowly as she’d been shaking her head a moment ago, yet still managing to evade my hand. “It’s something more than just stress and worry, Andrew.” She took a breath, and in that instant I could tell she had been concerned about this for much longer than I realized. “Do you not want to have this baby with me?”

Her words struck me like a mallet.

“Hey,” I said. “Listen to me. I want nothing more in the world than to have this baby with you. Am I scared? Yeah, okay, I’m scared. But I will get through it.”

“We,” she said. “We will get through it.”

“Yes,” I said. “We.”

“And that’s it? That’s all this is?” She was watching me with some lingering measure of skepticism, her jade eyes having narrowed the slightest bit.

“That’s all this is, I promise.”

And then we stayed there like that for several heartbeats. Those luminous green eyes, sucking me in like twin tractor beams . . .

“Okay,” she said eventually, turning back to her manuscript, and just like that the spell was broken.

* * *

Five months into the pregnancy, I was on the subway heading home from work when I glanced up and saw an advertisement that depicted a fireworks display over New York Harbor. I stared at it, became transfixed by it, just as the lights in the subway car began to flicker. I grew unsettled and twisted around in my seat. My shirt collar suddenly felt too tight, and I could feel a bead of sweat roll down the left side of my ribs. In the grimy window glass beneath the advertisement, my reflection stared back at me. I took in the drawn lines of my face, the haunted, weary expression that made me appear much older than my thirty-five years. When the lights went dark again, my face became a smudged black nothingness right there on the glass. The roar and hiss of the train sounded like those fireworks come to life. I shifted around uncomfortably in my seat again, and that black reflection in the window moved in a way I felt did not match my own movements. It was like looking at someone staring up at me beneath the surface of dark water—not a reflection at all, but an entirely separate entity. I watched as a spark of light flickered in the right eye socket of that black smudge of a face, or maybe it was something beyond the window in the subway tunnel that had flickered—either way, I felt my mouth go dry and my palms grow clammy. I was unreasonably grateful when the lights came back on, the doors shuddered open, and I could get off at the next stop.

* * *

Seven months into the pregnancy, lying beside me in bed, Rebecca said, “Do you still not want to know?”

“Know what?”

“The sex.”

Something tightened in my belly. I had been lying there with my eyes closed, attempting to force sleep upon me, but I was wide awake now, staring at the lights of the city through the slatted blinds of the windows across our bedroom.

“No,” I said, after a time. “I still don’t want to know. I can wait a couple more months.” I rolled my head toward her. She was already facing me, a pair of luminous eyes in the dark. “Unless you want to find out?”

“I don’t need to find out.” Her voice was a soft whisper, her breath warm and gentle on my face. “I already know.”

“This is mother’s intuition? Something you feel?”

“It’s something that beats in me like a pulse,” she said. “A little patter of Morse code, beep boop beep, right there in my temples, whispering to me in dots and dashes.”

“So what is it?” I asked her.

“You said you didn’t want to know.”

“Well, I want to know if you know.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“It’s a boy, Andrew.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. So I leaned in and kissed her. She kissed me back. A moment later, we were making slow, lazy love while someone’s car alarm fractured the night. When it was all over, she got up and went to the bathroom. I heard the shower clunk on, the old pipes shudder. That sliver of horizontal light beneath the bathroom door changed something in the bedroom—shadows seemed to rearrange themselves, items throughout the room furtively changing form.

Across the room, a figure stood just beyond the open closet door.

I sat up in bed, my flesh hotly prickling. I could see the outline of this person with perfect clarity, a black shape superimposed against the blacker background of my open closet. Most clearly, I could make out the tips of this person’s shoes, illuminated by the light spilling from beneath the bathroom door.

As I stared at the figure, I sensed its slow retreat as it receded, measure by measure, into the closet, its distinct, black silhouette growing more amorphous. As though it knew it had been spotted and was trying to quietly back away.

I climbed out of bed, went to the closet, and turned on the light.

There was no one there, of course. Just a file of dark suits, some boxes on a shelf, and a platoon of neckties hanging from a single wire hanger. I looked down and saw that those shoes I’d glimpsed were actually my own.

“Packing for a trip?” Rebecca said, coming out of the bathroom with a towel wrapped around her head, another around her torso.

“I thought I heard a noise,” I said, kicking my shoes deeper into the closet and closing the door.

“It’s probably the Constantines upstairs. They’re renovating.”

“At midnight?”

“Well, I sure as hell don’t want to think it’s rats.” She tossed both towels over a chair and climbed into bed. “Come,” she told me.

I crawled in beside her, the clean, warm smell of her body and the dampness of her hair splayed partially across my own pillow feeling like some perfect little snapshot of domesticity. I nestled my head in the crook of her neck. Her damp hair was cool against my burning face.

After a time, Rebecca’s gentle snoring pulled me down with her.

* * *

Eight months into the pregnancy, and my single-minded focus on work afforded me another win for the firm. To celebrate my success, Morrison threw a small bash at The Winchester, a private supper club in the Village, resplendent with plush club chairs, crystalline chandeliers, and a piano bar. I did my best to avoid conversation that evening, negotiating between the bar for beers and the back alley of the club to smoke cigarettes. On one pass, as I sidled up to the bar and ordered another Heineken, I sensed a shadow looming behind me. I worried it might be Morrison, but it was Laurie O’Dell.

“Counselor. How does it feel to be the man of the hour?”

“Oh, I don’t know about that,” I said.

“Don’t play coy.” Her smirk was darkly suspect. Laurie O’Dell was attractive, slightly older than me, and direct as an arrow. “Morrison can’t stop talking about you. It’s like you’re his long-lost son come back from the war. What’s gotten into you these past few months? You’re on fire.”

I looked across the club and saw Bryce Morrison surrounded by a cadre of dark-suited sycophants. They could have been vampires paying homage to their leader. As if sensing my gaze on him, Morrison glanced over at me, caught my eye, and raised his martini glass in my honor.

“It’s really kind of sick, don’t you think?” Laurie said, cradling a short glass of amber liquor in both hands as she leaned against the bar. “I mean, he knows you didn’t actually go to a real law school, right?”

“Harvard isn’t the only law school in the country, Laur.”

“Rumor has it Stein sent you a gold Rolex with ‘scot-free’ engraved on the back.”

This was only partially true: the Rolex sent by Remmy Stein had my name engraved on the back. It was currently tucked away in a desk drawer in my office, still snug in its velvet box.

“Don’t believe everything you hear, Laurie. Besides, everyone eventually pays in the end. You know that.”

“Now you sound like a choir boy.”

I laughed. “Far from it.”

She finished her drink and set her empty rocks glass on the bar. “Where’s your bride tonight? Doesn’t she want to bask in your glory?”

“She’s tired. Baby’s been restless.”

“Should be soon now?”

“One more month.” I nodded toward Laurie’s empty glass. “Refill?”

“If you’re buying.”

I ordered another Heineken for myself and a Macallan for Laurie, which made her chuckle.

“What?” I said.

“Be careful, counselor,” she said, and actually reached out and straightened my necktie. “Your blue collar is showing.”

It was then that I felt a gentle buzzing from the inside pocket of my suit jacket. I pulled out my cell phone, glanced at the unfamiliar number on the screen, and was about to decline the call when something gave me pause. Maybe it was the 410 area code that stopped me, or maybe it was that Morrison was headed in our direction, a toothy grin stretching the boundaries of his face; whatever the reason, I excused myself and hustled across the club toward the exit that led to the back alley, where I’d spent half the night smoking.

“Hello?” I said, answering the phone.

“Andrew? Is this Andrew Larimer?”

The voice was male, and it held the grogginess of someone freshly roused from a deep sleep.

“Who’s this?” I said.

“Andrew, this is Dale. Dale Walls. You know …” He cleared his throat, then added, “From back home.”

I pulled the phone away from my face, saw the Maryland area code for the second time, and became instantly aware of a cold, clammy sweat peeling down the center of my back. “Dale,” I said, the name coming out in a breathy whisper. “It’s been a long time.”

“Been a lifetime,” Dale said. “Look, man, I’m sorry to call so late. I’ve been drinking. And then I . . . I saw . . . something, I think …” He trailed off for a moment, with only his labored breathing on the line. Then: “It’s not a good idea. But listen, Andrew, I need your help.”

I closed my eyes. Said, “What’s wrong, Dale?”

“No. Not on the phone. I need you here.”

“Here?”

“Home,” Dale said. I heard a glass or a bottle clink in the background. “Kingsport.”

“What kind of trouble are you in, Dale?”

There was a beat of silence on the other end of the phone. I opened my eyes and saw my shadow stretched along the wet pavement of the alley in front of me, the lights of the city at my back—a distorted, alien shadow, long-limbed and monstrous.

“We got a lot of history between us, Andy.” He was breathing too heavily into the phone again, his words punctuated by expulsions of static. “I need you to come here, back to Kingsport, no questions asked. Just come home, and I’ll tell you everything. I’ll text you my address. Come tomorrow, Andy. As soon as you can.”

“Dale—”

“You don’t have a choice,” he said, and disconnected the call.

TWO

Around the same time I received the phone call from Dale Walls, a man named Matthew Meacham opened his eyes to a tomblike darkness. His body quaked, his mind raced, and his skin burned. He raked overlong fingernails down the tender flesh of his arms, praying for his eyes to adjust to the lightlessness. They never adjusted. After a time, he sat up in that dark space, feeling the elements of the world pressing against every inch of his body to inform him of where he was and what was about to happen.

What was about to happen?

“No,” he muttered, his lips unsticking with an audible smack. His tongue felt like a wool sock in his mouth. “Please, no …”

Nothing at first—except the distant plink plunk of a steady drop of water coming from somewhere. He picked himself up off the hardwood floor and stood upon a pair of creaky legs. What felt like large flies thumped against his face in the still and humid air. This man was thirty-five years old, but the things he had done to his body since his teenage years had come home to roost. His heart raced as he peered through that chamber of darkness for a sign of . . .

What?

“Robert?” he said, his voice a brittle snap in that bleak, sarcophagal place. “Is that you? Let me see you. Let me see you. Let me see—”

The smell of sulfur crept into his nose, causing him to recoil.

Meach summoned what fading flicker of courage he had left in him and staggered through a dark gallery of hallways and corridors, Theseus without his ball of thread, lost but blindly pursuing some internal patter, some broach of contact from another place, beckoning, tantalizing . . . a figure he believed existed even if it did not. In a spark of clarity, he recalled where he was—his old friend Andrew Larimer’s childhood home; my childhood home—yet that realization did not help anchor him back down to reality.

He kept thinking, Robert? Robert?

That sulfuric smell only grew stronger. Another smell behind that one—more earthy, brackish. Something of the land, and of the water that covers it.

And then he heard a voice, whispering in an almost singsong fashion: “One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

“Yes,” he said, the word, hardly a sound, an expulsion of air that wheezed from him as he staggered out into the warm, thick summer night in pursuit of that voice, his pores expelling gooey bulbs of perspiration. He dug his fingernails into his arms again, scritch-scritch-scritch, then focused his bleary eyes across a moon-wan night toward a stand of trees. Something shimmered in the dark. The boughs of the trees were wet and droopy from a recent summer rain, and if he listened carefully enough, he could hear the raindrops plinking from leaf to leaf, plunking in puddles cupped by black soil. Was that the sound he’d heard upon waking? Plink-plunk, plink-plunk.

A shape moved beyond the trees, causing him to freeze, his heart galloping in his chest. There was a crackle like static electricity in the air, and he became distantly aware of some transference taking place. Or taking hold.

(please no please please no)

The voice again, maybe in his head, or maybe calling out to him from just within the confines of those nearby trees: “One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

“What do you want from me?” he shouted hoarsely into the woods. “Why won’t you leave me alone?”

The voice repeated: “One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

“What—”

“Dig,” said the voice. And when he didn’t immediately oblige, the voice said again, more sternly, “Dig, Matthew.”

Meach felt his entire body shudder. He was hearing the plink-plunk again, and knew now without question that it was the sound of water dripping off a living corpse.

Something at his feet: he bent instinctively and drove his fingers into the moist soil, wiggling them around, feeling what was beneath the surface. Searching, searching. Nothing there. Nothing there. Searching some more. Thinking, This is it. This is the end. I’ve gone over the edge, like I always knew I would. Thinking of a boy who had once gone over—

(the edge)

But Meach did not go over the edge. This was not the end; more specifically, one might argue that this was the beginning of something, albeit something that owed its beginning to another time, another place. Whatever the case, tears dribbled down the waxen, pockmarked sides of Matthew Meacham’s face as he knelt there digging in the muddy soil.

“One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

A deep, shuddery breath, like the distant flutter of birds’ wings. Fingers working greedily in the dirt.

“One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

His fingers came into contact with a warm, moist cable buried beneath the earth. The feel of it caused him to pull away . . . but then something drew him back to it, and he gripped it tightly in both hands. It seemed to pulse against his palms as if with its own heartbeat. He tugged it out of the soil, uprooting it, and it came in segments, thuk-thuk-thuk, its wet, fibrous shaft thick as a powerline in his hands. It was an umbilical cord, or so his mind told him it was. He tugged at it with more authority, teeth gritted, but it would not uproot itself further. He took several steps forward and repositioned his hands along that slimy bit of rope, prying it out of the earth, thuk-thuk-thuk¸ the sharp little fibers bristling from the cord slicing through the soft meat of his palms, and Matthew Meacham, thirty-five years old, half a lifetime in and out of rehab and bars alike, his blood boiling with hepatitis, kept pulling, kept following the cord, kept pursuing his destiny.

It led him through a dense wood, where summertime trees, weighty with rainwater, bowed in supplication. He crossed beneath their boughs, forehead slapped by wet leaves, lacerated by pitchfork branches, blessed by the world around him, until he staggered out onto a muddy dirt road that overlooked the wide, black expanse of the Chesapeake Bay. He was suddenly standing on a platform at the edge of the world.

He paused for a moment, that taut umbilicus gripped tightly in both his bleeding hands, blood trickling blackly down his wrists. His lungs ached and his skin itched. His right eye was burning again, just as he claimed it had in the weeks after the incident back when the five of us had been teenagers. Beyond the road was a bluff that overlooked the tremendous expanse of the bay, ink-black and moonlight-shiny. It was a clear summer night, and even with Meach’s bleary, burning vision, he could easily discern the pulsating glow of the lighthouse out there, surrounded by all that darkness. The umbilicus was strung like a booby-trap beneath the road, leading toward the edge of the cliff; Matthew Meacham tugged at it again, and it broke incrementally free of the earth in little staccato reports, pop pop pop, right through the muddy surface. It tunneled straight through to the opposite side of the road, toward the edge of the cliff that looked out across the inky black waters of the bay. Still stubborn in its buriedness.

Matthew Meacham staggered toward the edge of the cliff. A dizzying euphoria overtook him, and he momentarily closed his eyes and swayed on his unsteady feet. His lungs, burning a moment ago, now felt heavy and full of some thick, viscous liquid.

Robert, is that you?

What do you want?

What is there to find?

And the voice responded: “One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . . five …”

The umbilicus grew taut once more, and he looked down to find it snagged between two large rocks at the edge of the cliff. He yanked on the cord, but it wouldn’t budge; his hands were slippery with blood now, and with whatever noxious fluid was seeping out of the cord itself.

No, not a cord.

A lifeline, he thought, for no discernible reason. A life—

The cord pulled back, and the next thing Matthew Meacham knew, he was tumbling over the side of the cliff, his heels carving trenches through the earth, then flipping forward, and he was airborne, head over ass, plummeting down, down, down . . .

In a flash, just before he struck the earth below, he thought he saw the figure of a teenage boy standing in the shallow water, watching him fall.

THREE

I’ve got a book, The 365 Greatest Things Anybody Ever Said, which my father gave to me upon my admittance to law school. The concept is like one of those word-of-the-day calendars, only it’s a book, and they’re famous quotes instead of words. In it is a quote from William Faulkner, from his novel Requiem for a Nun, I believe. I’m pretty sure you’ve heard it: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

That was what it was like returning home.

Kingsport, an animal, carries upon its hide the fleas of humanity: chafe-knuckled watermen, sun-browned faces, the squinting, rheumy eyes of career alcoholics. Live to eighty, and you’ve gone blind from a lifetime staring at the reflection of the sun off the bay. Garrulous, whiskied female laughter cackles through the open doors of the dock bars in mid-afternoon. Seagull shit plasters the hot tracts of asphalt that cut beelines through cornfields and sand dunes alike, as it does the gas station parking lots, the cars and trucks, the palmists’ hand-painted wooden signs, the neon lights of the Stop and Go out along U.S. Route 50. There’s always some guy with his shirt off on a bike, calf muscles like machine parts, baseball hat backwards, Ray-Bans on, pedaling with a basket on the front (sometimes there’s a transistor radio jouncing around in that basket, sometimes a large, bored-looking cat). The boats down at Kingsport Marina are sad refugees, barnacle-clad and hopeless, with hulls like rusted torpedo shells. They’ve got faded names stenciled across their sterns—Rudder Disregard and Cirrhosis of the River and In Decent Seas—and there are fishing nets draped over the sides of these vessels, and crab pots stacked like Egyptian monoliths on their moss-slickened decks. You can see the line of houses along the coast, with their storm windows at the ready, satellite dishes on their sun-bleached roofs. You can see, too, the tracks cut into the marshland by the rugged, unforgiving tires of all-terrain vehicles, and the litter of empty beer cans their riders leave behind in their wake. The bars stay open all hours of the night out here, filling cups for as long as there are patrons planted in seats to knock them back, county regulations be damned. They smoke, they fight, they sleep with each other’s spouses. They spew racial epithets like it’s some call to arms. Men here still call women “sweetheart” and “doll” and “babe,” and the women take this without an ounce of resentment, or even the most remote inkling that something is out of balance; it’s as if, at some pivotal juncture in their collective upbringing, their mothers had taken them out to the barn and explained, quite simply, that this is just the way it is, and now they carry that knowledge as some unknowable burden across their bowed and strained shoulders like sacks of wheat. The smell of the bay is year-round out here—a briny and vaguely fetid stench that becomes completely overpowering during the hottest, driest times of the summer. The beaches are littered with eviscerated clam shells, and mayflies congregate in knots in the air. Oyster beds are in such abundance, they crest above the surface of the water in bulging, irregular black pylons and gleaming, otherworldly outcroppings, so many it’s like a breaching of a pod of humpback whales. Sometimes, you’ll find a dead seagull snared in the reeds, its body garroted by fishing line, its red bill hinged at a ninety-degree scream, one blind, milky eye bulging from its black-hooded face.

As far as Rebecca was aware, Baltimore was my destination, where I’d meet with one of Bryce Morrison’s legally challenged, unscrupulous clients. I told her nothing of the phone call from Dale the night before, nor of the text message I’d received from him this morning with his home address. I’d lied to her as I packed my bag in our bedroom, apologizing for having to leave her last minute on a Saturday and because I wasn’t sure how long I’d be gone. She cursed Morrison under her breath for working me too hard, then made me a sandwich to eat on the train. And while I did take the Amtrak to Charm City, with its confusion of fire-scarred warehouses, Everest-like salt mounds, and winding, concrete ramparts like something out of a post-apocalyptic nightmare, I didn’t stop there. Instead, I rented a car and took I-95 to U.S. 50, which shuttled me across the Bay Bridge. Far below, the Chesapeake lay sculpted in broken glass and streamers of molten metal, while a procession of cargo ships sat motionless on the horizon.

I’d spent the first eighteen years of my life in Kingsport—a small, insignificant creature bobbing along the whitecaps of this small, insignificant fishing and crabbing village, tucked behind fields of corn and wheat, bracketed by steel grain silos and CITGO gas stations, and flanked by the black-rock cliffs and brown, reedy beaches that comprised Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It was a waterman’s town, and nearly everyone who lived there made their living off the bay—crabbing, fishing, oystering, sailing. The crabbing and fishing boats would go out before dawn and return around suppertime, catch or no catch, and on quiet nights as a child, with my bedroom window open to let in whatever breeze there was to come on through, I could hear their mournful clanging down at the Kingsport Marina far across town. On clear nights, if you traveled the old Ribbon Road straight out to the cliffs of Gracie Point, you could see the lighthouse in the distance blazing like the finger of God in the middle of the bay; on foggy nights, it was still visible, only now as a smudgy cigarette burn poking dreamily through the misty veil.

When my father died six years ago, I became the sole owner of my childhood home. A rambling ranch-style farmhouse that had been in my family for generations, the only house on acres and acres of land, mostly hidden from the road by a confusion of overgrown, jungle-like trees, and a low chain-link fence woven with poison ivy. My father had been an attorney—a small-town lawyer who might have been destined for bigger things but was too preoccupied with raising a son on his own to pursue them—and he was a good man. He did his work from the house in an office in the back. He kept a wooden shingle dangling from the porch that said, simply, E. LARIMER, ATTORNEY-AT-LAW. While his profession obligated him to sit behind a desk, my father was also not afraid to get his hands dirty, so when he wasn’t poring over clients’ legal documents and offering advice on the occasional dissolution of a marriage, Ernest Larimer kept the old ranch house up as best he could. He’d do all the repair work himself—any necessary carpentry, but also plumbing and electrical work—and I have vivid memories from my youth of his broad shoulders sweating through the fabric of his threadbare work shirt, his eyes the color of steel pins narrowing in concentration, the beads of sweat trickling down his reddened, furrowed brow.

The last time I’d set eyes on the house—on this town—had been the week I’d come home to bury my father at St. Gregory’s. It was a distant memory six years gone, but the emotion, I found, was suddenly very close to the surface as I turned the steering wheel of my rental car and pulled up the old gravel driveway. It was the same house, of course, but there was something hazy and remote about it now, noncommittal almost, like an image from some vaguely remembered dream—or like the Gracie Point Lighthouse on those cold, foggy nights.

Uncertain what I wanted to do with the place after my father’s death, I opted to hold onto it for a while. Since I was already living in New York at the time, this required me to hire a caretaker to mow the lawn, trim the hedges, and just generally make sure the place didn’t crumble to a pile of ash in my absence while I was still considering what I should do with it. Having kicked that can six years down the road now, and I was still forking over quarterly paychecks to Gil Wallace, the local caretaker.

As I pulled up to the house, I saw a rust-red pickup truck parked at an angle at the top of the driveway. Gil Wallace himself was leaning against the driver’s door, smoking a brown cigarette and mopping the sweat from his creased and sunburned forehead with what looked like a dirty oil rag. I’d phoned him ahead of time to inquire about the condition of the place, since I’d planned to spend the night here, and he’d assured me all was tip-top, Mr. Larimer, sir. I hadn’t asked him to meet me here, yet here he was, sweat boiling off his flesh while he sucked the life out of that cigarette.

What the hell am I even doing here? That I’d come running back to this place in the wake of Dale’s cryptic phone call only confirmed how deep some roots grow.

Gil squinted at me, shielding his eyes from the setting sun, as I shut down the rental car’s engine and climbed out into a swampy summer heat. Despite having spent the majority of his fifty-odd years doing manual labor in this town, Gil Wallace was an errant hangnail of a man, his loose skin like football leather. His shoulders came to points and his legs were noticeably bowed. He wore a belt that could have wrapped around him twice.

“Nice trip down, Mr. Larimer?”

I crossed over to his truck and shook his hand. “You didn’t have to meet me here, Gil. I’ve got a key. How long have you been waiting?”

“Well, now, wasn’t much waiting as I was getting some things ready for you, Mr. Larimer. Last minute notice and all, but I wanted everything to be good to go, sir.”

“I thought you said the place was tip-top,” I reminded him. “And please, call me Andrew.”

“Oh, she is, she is . . . the place, I mean . . . only, well …” He twisted up his face into some semblance of a frown or a scowl—I couldn’t be sure which—and then I watched as his cigarette rolled from one corner of his mouth to the other, like some magic trick.

“Well what?” I said.

“Well, I hate to tell you, but I think you had a squatter.”

“A what?”

He pointed in the general vicinity of the house. “A squatter, Mr. Larimer. Someone broke in through the back door—I only just realized it today, when I was giving the place a final once-over for you—and they was living in there, I think, for a time. Found some fast-food wrappers, beer cans, stuff like that. Even some clothes and an old sleeping bag and backpack, which I took straightaway out to the trash.” He raked a set of fingers through his short, silvery hair, and I watched as dry flakes of scalp trampolined into the air. “Of course, it could just be neighborhood kids, breaking in here to have a good time. You know how kids are.”

“Great,” I said, looking up at the old place.

“Anyway, I replaced the lock on the back, where it had been jimmied, and like I said, I cleaned everything out. Water’s working, electric’s on.”

Sudden movement in the periphery of my vision caught my attention. I looked up in time to see a pair of massive black wings swoop down from the roof of the house and coast over to a low tree branch in the front yard. The thing settled there, the branch bowing under its weight. It was a turkey vulture, one of God’s ugliest creations. I glanced up at the roof and saw two more perched up there like sentinels.

“I hate those things,” I said, more to myself than to Gil Wallace.

“Well, they’re ugly as sin, but they won’t hassle you. They’re carrion birds.”

“Why are they hanging around here?”

“Maybe something has died,” Gil suggested. Then he shrugged his shoulders and added, “Or it could just be the smell.”

“What smell?”

He looked suddenly sheepish as he blotted the sweat from his brow again. “There’s a godawful smell in the house, Mr. Larimer, just to warn you. Did all I could about that, some air fresheners, sprays and whatnot, but I’m afraid it’s a stubborn stink. Smells like death, so maybe that’s what brought the birds. And of course, the stink brings the flies, too. Did what I could about that, as well, Mr. Larimer, but I’m afraid it ain’t been enough.”

“Flies?”

“Afraid so, Mr. Larimer. Big black ones. Droves of ’em.”

Gil followed me up the porch and was already digging a ball of keys out of his khakis when I said, “It’s okay, I’ve got it.” I took a key fob that said DAD’S HOUSE from my pocket. Before unlocking the door, I observed my father’s shingle, still hanging there by a pair of rusty chains—E. LARIMER, ATTORNEY-AT-LAW.

I stepped inside a tomb, where the air sat stagnant and foul-smelling and humid as a sweatbox. Flies swarmed the air all right, the tiniest of them clustering around my nose and eyes. Strips of flypaper hung from the ceiling, so many brown, curling bits of tacky paper that they looked almost festive. I fanned flies from the air as I came through the door, and saw them swarming along the walls of the hallway.

“You weren’t kidding,” I commented.

Despite the infestation, I could see the place was mostly clean—old Gil had been busy all afternoon, eager to impress—and when I went to the sink and turned on the faucet, the old caretaker made a sigh of relief as crystal-clear water chugged unimpeded out of the tap.

“See?” he said, blotting dead gnats from his sweaty forehead with his dirty rag. “Tip-top.”

“You’re right about that smell, though. What is that?”

“I think,” Gil said, “that if you keep the windows open for a bit, it might air the place out.”

I nodded, although I knew this wasn’t the smell of mustiness. The house smelled putrid, as if something dead was rotting away in here.

“You want me to bring your bags in from the car, Mr. Larimer?”

“That’s all right, Gil. I’ll take care of it.”

“How long you staying for, you don’t mind me asking?”

“I’m not really sure.” I pinched a curled section of wallpaper between my thumb and forefinger, and gave it a decisive tug. It was so brittle, it made a sound like tearing burlap as it came away from the wall, and expelled a clot of dust particles into the air. “If this smell doesn’t get any better, I might just get a room out by the highway. These flies aren’t helping matters, either.”

“Chicken necks,” Gil said.

I looked at him. “What’s that?”

“You ever hoist a crab trap from the water that’s got chicken necks in it? Been under for a few days? That’s what this smells like.”

“Chicken necks,” I muttered.

“Crazy thing is, I was out here just last month, Mr. Larimer, and everything was tip—”

“Was tip-top, right,” I finished for him.

“Room by the highway might not be such a terrible thing, is what I’m thinking, Mr. Larimer. Meanwhile, I could get an exterminator in here. Someone to come see about the smell.”

I told him that wouldn’t be necessary, thanked him for his help, then handed him some extra cash. He blotted his brow with that rag one last time, then tromped out of the house. I listened as his rattletrap pickup shuddered down the driveway toward the road.

What am I doing here?

I had never properly cleaned the house out after my father’s death, so most of his belongings were still here—the kitchen table, the sofa and loveseat in the den, the bedrooms perfectly made up. His personal effects still resided here in the house, and it would be easy to believe he was still alive and well, with his pipe on a stand in the living room, a rack of magazines in the vestibule, an old percolator on the stove, polished and shiny as an old Chevy fender. I meandered through the place, taking it all in, like a spectator despite the fact that I’d spent the first eighteen years of my life living inside these walls. The floral-patterned wallpaper, the arched doorways, the multitude of claustrophobic little rooms with their hodgepodge assortments of furniture—this place felt like a shoe I’d outgrown. My mother had lit out for the Great Beyond when I was just a toddler, so it had just been my father and me for all those years, without so much as a modicum of female jurisprudence to brighten our lives. We were just two men, bound by blood, negotiating the creaky corridors and passageways of this cramped and musty dwelling. This house never felt more like that to me than it did now—a thing whose sole purpose was to contain.

I peered into the parlor with its scuffed hardwood floors; a closet off the laundry room with a collapsible ironing board protruding from it like an obscene gesture; the kitchen with its antique appliances; my father’s office, with its shelves of ancient hornbooks, a desk with a dusty ink blotter, a silver letter opener, and a mug that said SHOW ME YOUR BRIEFS. There were photos of me as a child in this room, fishing rod in hand, or a baseball bat slung over one shoulder.

I went down the hall to my childhood bedroom last. I’d packed most of my things once I left for college, and then packed up the rest when I’d returned six years ago to bury my father, so all that remained in this room now was a single twin bed, a too-small desk, a dusty wall mirror, and a braided throw rug in the middle of the floor. There was a nightstand, too, with an old lamp on it. I stared at it for several seconds—or, more precisely, stared at the nightstand’s single drawer. It can’t still be in there, I thought, then on the heels of that: Where else would it have gone?

I pulled open the drawer. Inside was a tattered paperback copy of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. The sight of it caused my throat to constrict. I took the book out, and thumbed open the cover. Printed on the title page in a faded, feminine script were two words:

burn bright

I slipped the book back in the drawer and closed it.

On my way out of the room to retrieve my luggage from the car, the toe of my right foot struck something, sending it rolling across the hardwood floor. I glimpsed it disappear beneath the bed.

Getting down on my hands and knees, I peered under the bed and at a vast sea of dust balls until I spied the thing—a narrow, cylindrical tube with some writing on it. I reached for it, drew it out, then knelt there staring at it as it lay like some talisman across the palm of my hand.

It was a Roman candle, hollowed and spent, with a fringe of burned paper on one end. The waxy black wrapper felt almost greasy in my hands, and despite the burned edges, I could still read the words in jarring red font—MAD DOG TNT.

Reality grew fuzzy around the border. Even as I stared at it, I wondered if it truly existed, or if it was some hallucination from my past, conjured up by my overtaxed and stricken mind.

I brought it to my nose, gave it a sniff. The stink of black powder was so caustic that it burned my sinuses and caused my eyes to water. The Fourth of July was soon approaching, so it was perfectly logical to think that some local kids had broken in here—squatted, as Gil Wallace had said—and had shot off some preliminary fireworks on the property. Wanton boys with cigarette lighters and too much time on their hands were a staple of Kingsport. Why the spent cartridge was in the house, however, I couldn’t fathom, but it was all perfectly logical. Or so I convinced myself.

I placed it on the nightstand beside the bed. Kept staring at it even though I had suitably rationalized its existence to myself a moment ago. The waning daylight coming through the single window above the bed cast a spotlight on it, or so it seemed.

I decided to go around and open all the windows in the place. I doubted it would do much good against the stench, but it was worth a shot. If I came back here tonight after meeting with Dale and it still smelled this awful, I’d pack up and find a motel out by the highway.

Outside, the light was growing dim, and I was exhausted from the trip down, so I knew I needed to head out to Dale’s before it got too late. I checked into some fresh clothes—an Oxford shirt, pleated slacks, considered a necktie then thought better of it—then brushed my teeth and combed my hair in the hallway bathroom. My father’s toothbrush still sat in a plastic cup atop the sink, the medicine cabinet still chocked with his various ointments and pills and plastic hair combs.

I closed the medicine cabinet, then stood there looking at my reflection. Stared at it. Felt something uncomfortable rolling around inside me. A dark wraith come home to roost.

The last thing I did before leaving the house was to pull my wedding band off my finger and leave it on the bathroom sink.

i

There is a gas station on the outskirts of my hometown of Kingsport, Maryland, that is just your average, run-of-the-mill gas station and convenience store, except for the fact that it has a large green frog floating in a jar of formaldehyde on a little pedestal next to the coffee station. The frog looks frozen in some perpetual surprise, its buggy eyes forever staring, its abbreviated forepaws thrust out in a simulacrum of shock. Even its webbed toes, splayed like a newborn’s, suggest that this creature was just as surprised by its arrival on this planet as those who found it.

There is a plaque on the jar, a little plastic sign fixed to it by Tacky Tape, that reads:

“RAIN OF FROGS”

SUMMER 2003

For those curiosity-seekers, there is a man who doesn’t necessarily work at that gas station, but rather lingers like an odor, shuffling up and down the aisles, the cuffs of his pants frayed, his brown feet in sandals, one eye milky from glaucoma. For a dollar, he’ll talk to anyone who comes in asking about that frog. He’ll talk about the strange happenings in the summer of 2003 in the Eastern Shore town of Kingsport, Maryland—the witchcraft that befell the populace, the strange storms, the horrific nerve-shattering majesty of it all—and his half-blind eyes will go wide with the retelling, as if he’s just hearing this business himself for the first time in his life, stupefied by the grandeur of it all.

When he’s done, he’ll make sure you peek in at that frog, just take a good long gander at the old gal, and as you’re doing that, this man will creep up beside you, those sandals shushing mutely on the linoleum tiles of the convenience store’s floor, and whisper into your ear: “It came right outta da sky, saw it wit m’ own eyes, I did. Wit m’ own eyes.”

And the smell of him will drive you right back out to your car.

FOUR

The address Dale had texted me took me straight through town and out to a new housing development on a cliff overlooking the Chesapeake, where all the homes looked brand new and vacant. A large white construction sign stood at the entrance of the development, the company name—Four Walls Construction—emblazoned in three-foot-tall letters. Dale’s house stood at the end of a freshly paved cul-de-sac, a handsome white Colonial with polished stone columns on the porch. A brand-new Lincoln Navigator, battleship-gray, sat in the stamped-concrete driveway beside a more economical Prius. Beyond the house was nothing but a swath of deepening sky hanging over the vast gray slate of the Chesapeake Bay.

I parked on the street and climbed out just as a procession of lampposts winked on up and down the block. It seemed almost orchestrated. The street itself was eerily silent, and I could see that Dale’s was the only house with vehicles in the driveway and lights on in the windows.

I went to the front door and was about to put the heavy brass knocker to work when the door swung open and a woman nearly slammed into me. I jumped back, and she made a squeaky little cry of surprise.

“My God, you scared the life out of me,” she said, and actually placed a hand to her chest. I saw a small boy, maybe eight or nine, standing beside her, gazing up at me from beneath a fringe of licorice-black curls.

“I’m sorry, I was about to knock. I didn’t mean to—”

“It’s Andrew, right? Andrew Larimer?”

“Yes, I—”

“Suzanne,” she said, and afforded me a curt smile. She was maybe forty, but the evident stress lines carved into her face seemed to age her to some indeterminable number. “Dale’s sister.”

“Of course,” I said. “I remember. I’m sorry, I’m a little fuzzy from the trip down.”