0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

The first time beautiful, wealthy Lisle sees John, she knows she loves him. But can this handsome John Sargent overcome grave danger and deceit to save his country - and the woman he loves?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

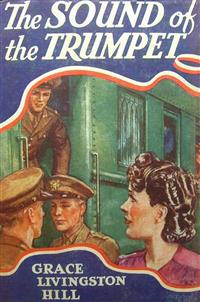

Sound of the Trumpet

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1943

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Sound of the Trumpet

by

Grace Livingston Hill

Chapter 1

Eastern United States 1940s

Two men sat in an office of a large warehouse, at this hour almost deserted by the main force of workers who usually swarmed everywhere. Though they felt they were alone and safe from all listeners, they spoke in low tones, guardedly.

Weaver, the older man, was large and heavyset, with sharp eyes and firm lips. When he spoke he seemed to dominate the room, as if somehow he had acquired authority over the whole universe.

The other man was smaller, keen-eyed, with caution in his glance. His name was Lacey, and although he was subordinate, he was the more knowledgeable of the two. He was studying the other man as he talked, weighing his words, sifting his expressions.

“We have definite information that the model has been completed and is now in the hands of the manufacturer.” Weaver spoke with heavy emphasis.

“Has it been tested?” asked Lacey sharply. “Are they sure it will work?”

“Oh, yes,” said the boss impatiently, “it’s all been worked out. That’s why it’s important to get this thing going at once. If these things can be manufactured fast enough, it will simply revolutionize this war. Anyone with this equipment will be the winner. It depends on who gets there and gets it to working first. And that’s why we have to find out just what their secret is. We think we know, but we’re still a little vague over a few points. And that’s where you come in. It’s up to you to get drawings, measurements, dates when they plan to ship, all the items you think we will need.”

“You mean to plant me somewhere to find out those things? But man, that’s entirely out of my line.”

“Of course not, Lacey! I mean you’re to contact the man we suggest, or if that doesn’t work out, then find the right man. One with common sense to keep his mouth shut and work in the most casual way so there will be no hint of suspicion stirred up while he gets all the information we need. It’s nothing new to you, Lacey. It’s much along the line of your last job, only a thousand times more important. And we think we have the right man, but it will be for you to contact him through your usual workers.”

“I see,” said Lacey. “Who’s the manufacturer? Or isn’t that definite yet?”

“Oh yes, that’s definite all right. It’s not just one manufacturer, it’s two. The way they’ve got it worked out, Vandingham and Company have the main part of the work, and Windlass, Cooper, and Crane have the ‘accessories.’ That’s the way they are talking about it among themselves—‘Just a few small gadgets,’ they say. But it happens that we know these gadgets are the most important parts when they are in the main machine. And then there is a third plant involved, a smaller, insignificant plant that Vandingham and Company are secretly taking over. It’s a little dump, not well known, and there they mean to assemble the whole, and feel quite sure the world at large will never dream that anything important like that is going on there. The buildings have been somewhat altered so that they are quite inaccessible to the public, or even to other workers in the same operation, and it will not be known that it has anything at all to do with Vandingham’s. It’s been very cleverly thought out, and it was only by chance that we happened to hear about it through a man who delivers material to them, and he didn’t know he was telling us anything. One of our men worked it out of him bit by bit as they were loading up their trucks. He was canny enough to ask the right questions about where the material was being taken, and didn’t Vandingham buy that other plant? So we put two and two together. We’ve got ’em all watched.”

“And you mean I’ve got to get a worker in each one of those plants?”

“No, no, not that, Lacey. We’ve got it all worked out, I tell you. You see, it is rumored that young Vandingham is taking over the main office in his father’s place this fall. It might be part of a plan to keep him out of the draft, perhaps. But anyhow, he’s to be there this winter, and the idea is—”

“To try and get his father’s secrets out of him?” interrupted Lacey. “You could never do that! I know those Vandinghams. They’re proud as peacocks of their name and position. They would never give each other away, not even if they were having a real civil war in private among themselves.”

“No, they would never give away their own secrets. But someone else could do it. Someone who knew them well, who was in their confidence and hadn’t any idea how important it was. And I think I’ve found the very one for you. A young fellow who was in college with young Vandingham and is rather up against it financially himself. It’s up to you to offer him a good sum to get some of those figures and plans and formulas we need. First, that we may be able to produce the same thing, perhaps even better than they are planning, and second, that we shall know exactly where and how and when to strike in order that we may destroy their work before it ever gets to the Allies.”

“I see,” said Lacey. “A fine scheme, if it all fits. But I’d be leery about getting the right man into that outfit. I’ve always heard that gang are pretty doggoned smart, and they don’t take every Tom, Dick, and Harry in with them, even if they do happen to have gone to college with Papa’s little boy. However, I’ll do my best, of course. But who’s the lad? Do I know him? Is he known in the city?”

The big man looked at him keenly.

“No, he’s not very well known. You wouldn’t know him. He’s only a bright kid, just came to the city this summer to look after a sick grandmother. His folks are dead and he worked his way through college, but when his grandmother took sick he left a pretty good job he had in the West and came here to look after her. He’s been working around at anything he could get since he came, but he’d be open for a good job, because he wants to take care of the old lady. She hasn’t anybody else. She’s been a librarian for years, living alone, but she had a stroke or two, and I guess she’s pretty bad off. Anyhow, we found out he’s looking for something really good so he can take care of her properly. It seems she did a lot for him when his folks first died, but about two years ago she lost all her savings in some fool investment, and now he feels it’s up to him. So, you see it would be easy to get a hold over him. He’ll probably snap at the chance. I want you to have him approached by a man who’s always been pretty successful getting such jobs across—perhaps Kurt Entry—and I haven’t a doubt but he’ll be putty in our hands. So now it’s up to you to place him and then keep in touch with him.”

“Where does he live?” asked Lacey.

“Just now he’s in the quarters where his grandmother has lived for some time—143 Burton Street. But I wouldn’t advise youto be seen going there. We’ve got to work this thing most cautiously, you know.”

“Oh, of course. But I’d want to look the lad over before I undertook this. Personally, I think a girl would fit into that outfit better than a young man. She’d be more likely to pick older men in a place like that, not a kid, especially for a job as particular as you say this is.”

“Wait till you see the fella. He’s very dependable—had to knock around a lot. And keen. Besides, I doubt if they’d let a girl get into the place, not on a job as secret as this one!”

“There are always ways for a girl to get places, especially if someone is sweet on her. I understand that young Vandingham likes pretty girls. I know a girl I believe could get almost any young fella to show her around the plant where he worked.”

“Not a plant like that!” said the older man. “Not a government secret! You try this fella first. Then if we can’t get him, or somebody better, we’ll see about the girl.”

“Okay,” said Lacey. “I’ll look him over. What’s his name? Where do I meet him? Has he a telephone? How do I contact him?”

“Name is Sargent. John Sargent. Here are the facts,” said the big man grimly, handing him a folded paper. “Better let your man contact him and feel around how he stands before you make an open proposition. If it’s necessary to offer a larger salary than I’ve suggested, go ahead, of course. The main thing is to get the right man and get him quick. We don’t want that invention to slip out of our hands. And Lacey, be sure you get him one of those new concealed cameras. They’re as inconspicuous as a coat button. Better instruct him to get pictures of everything, and absolutely on the QT. Of course, they wouldn’t let a camera pass the door if they knew it was there. It’s got to be mighty slick work, you know.”

“Of course,” said Lacey. “What do you think I am, Weaver? A child that needs a nurse?”

“Well, I’m just telling you,” warned the boss. “You know who we’re answering to, and you don’t want to get into trouble yourself, do you? Now go. I’ve got another appointment in five minutes, so I guess you’d better fade away before my next man appears. And Lacey, just remember, don’t come here unless I send for you. It won’t be good if we’re seen together too much.”

“But suppose I need to report to you. Do I phone?”

“Only at the prescribed times and places. You’ll find a note in your papers. That’s all, Lacey. Meantime, keep that girl you spoke of up your sleeve for an emergency. Good-bye!”

Lacey stole out a side entrance and disappeared into another part of the building, and a group of three were announced and took his place.

Lacey went by a back way to a rooming house and locked himself into his gloomy little room, where he sat down to study the paper Weaver had given him.

The paper was typewritten, largely in code.

For some time Lacey sat studying it, frowning, tapping his finger nervously on the arm of his chair, staring at the words on the paper until they were fairly imprinted on his vision. Then suddenly he was startled by the ringing of his telephone, and he hurried over to his desk to answer it.

“Are you number twenty-three of the troop of investigators?” a strange voice asked.

“Yes,” said Lacey sharply.

“Then the orders are for you to proceed to Main Street between Twelfth and Fourteenth at once, and observe the workers among the water company emergency men. You can see the person under discussion among them, bareheaded, wearing a blue shirt, with light curly hair and blue eyes. Walk slowly, pausing now and then casually to watch the workers, then proceed down the street to Filmore’s Garage, returning five minutes later, walking more briskly and not seeming to notice one laboring man more than another. You will receive another phone call at one thirty. That’s all.”

Lacey took his hat and hastened away.

Lisle Kingsley, walking with her father and mother from Filmore’s Garage, where they had left their car, to her father’s office, half a block farther on, was halted by an obstruction on the sidewalk. There had evidently been a burst water main that had flooded the street, and the men from the water company were working valiantly to open the road and find the broken pipe that had caused the trouble. Some of them were apparently new at the job and not as careful as they should have been to keep the mud and rubble from the sidewalk, flinging dirt and paving blocks and muddy water out of their way and not stopping to see where they landed until large piles had mounted up across the pavement.

Mr. Kingsley stepped out into the road to investigate and ask a few questions, as the obstruction was almost in front of his office. A number of people were hesitating in dismay, gazing anxiously down at their shoes and wondering which was the best way to get across. Traffic had been stopped by the spouting water and its consequent flooding of the street, and the road was pretty well congested with trucks, delivery wagons, and cars. It was also very muddy, as in places the pools were still quite deep, though the water had been turned off for several minutes now.

Just ahead of Mrs. Kingsley and Lisle were a group of irate ladies, one of whom was storming at the men who were working so frantically to put things right.

It was at this moment that Lacey arrived among the crowd.

“I think this is perfectly inexcusable!” said Mrs. Gately, a recently rich woman who had married wealth and intended everyone should understand her importance. “Why can’t you men keep this rubbish off the sidewalk? It could just as well be left in the road. Just look at my dress! All spattered with mud and filth! And it’s an imported dress! Probably the last one I shall ever be able to get from Paris unless this horrid old war stops pretty soon. And they say Paris will be practically destroyed before it does. That is, the old Paris, where all the fashions come from! There! Now you’ve done it again! Flung a lot of slushy mud over my shoes! I think you men ought to be arrested! I shall ask my husband to have your names taken and see that something is done about this. I shall certainly report you to the officials of the water company, and you men will all lose your jobs! Then perhaps you will learn that you can’t obstruct the sidewalk from the garage to the shopping district. I mean what I say! You’ll find out! What’s your name, young man?”

She pointed her beautifully manicured, crimson-tipped forefinger straight at a young man in a light blue shirt, who was shoveling vigorously in the forefront of the workers. He looked up with a quick amused glance.

“Yes, you! You’re the one I mean! You flung that water right on my foot! I saw you! How long have you been working for this water company?”

He gave another quick grin and answered in a clear young voice, “About twenty minutes, madam. They were short of help and this thing was getting ahead of them. They asked me to lend a hand. But madam, if you would just step back a little, or go around the other way, you wouldn’t be in danger of getting your shoes any wetter.”

“You’re impertinent!” said the lady, stepping a little nearer instead of backing away. “Don’t you dare throw any more water on me, or I’ll have you in jail before you know what it’s all about.”

The young man did not answer. He kept right on working and then suddenly lifted his eyes and swept the crowd with a quick questioning look, and his eyes met Lisle Kingsley’s. Their glances held for an instant in mutual amusement and contempt for the woman who persisted in trying to hold the center of the stage.

It was just for a moment, and then the boy dropped his gaze and went on with his work. He had nice eyes, Lisle decided. It seemed that suddenly they were acquaintances in understanding, one in contemptuous amusement.

Then the boy lifted his eyes for another fleeting look, saw a tiny hint of a smile on the girl’s lovely lips, and there was an answering grin on his own face. Lisle had time to notice that his blue shirt was just the color of his eyes, and his close-cropped curls caught the bright sunlight like a spot of beaten gold. He certainly was a personable-looking young fellow, even if he was doing the work of a day laborer, and she noticed that he was not slinging mud toward the arrogant, expensive shoes of the brawling woman, who continued to address him as though he were the chief offender in her world. Though the same could not be said of two or three other men who were working shoulder to shoulder with him, for they seemed to make a special point of slinging all the slime of the street toward the offending women. And one aimed a neat shovelful of dirty water and stones full on the tiny foot of the lady, soaking her delicate hosiery with a great black stain.

“There!” she shrieked, turning a baleful glance at the blue-eyed boy again. “Look at what you have done! Now I’ll have it back on you. These were absolutely new stockings and shoes, and you’ve simply ruined them! And you did it just for spite. You shan’t hear the last of this in quite a while! And I was going to luncheon this noon! How unbearable! Well, you’ll have plenty of chance to think this over in jail and be ready to apologize, and then work after you get out to pay for them, too! It’ll cost you plenty!”

Suddenly the big lowering man turned on her.

“You’re all wrong, ma’am! You’re completely off base! You’re barking up the wrong tree! That kid didn’t sling that mud on you. I done it myself, and I’m glad I did, do ye hear? If you don’t know enough to get out of the way when you’re hindering our work, it’s too bad for you! And if you stick around here any longer, I’ll do it again! Now, get out of the way, unless you want some more of the same kind, and I don’t mean mebbe! You can go talk to the water company if you want, but you can’t get nothing on us. We’re not the water company! We’re just volunteers, passersby, helping out in an emergency! The head man of the water company is standing over there in the road in the middle of all that water. If you want to talk to anyone, paddle over there and talk to him. Now,scram!”

Mrs. Gately blinked and spluttered at the man, her face livid with anger.

“Why—you—you—outrageous creature!” she shrieked. “Who are you, anyway? To speak that way to a lady!”

“Oh, is that what you are? Okay, boys, sling your mud. The ‘lady’asks for it!”

He stooped to drop his shovel into deepest mud and turned with the evident purpose of planting an ample quantity straight on the tidy little Gately feet. Suddenly Mrs. Gately started screaming and trying to back out of the crowd, but by this time the crowd had closed up behind her and there seemed no way through. Then the lowering man and a couple like-minded evil conspirators, seeing their chance, slung a goodly portion of wet dirt over the imported feet. The furious woman, raising a frantic howl, took a slide on the muddy pavement and sat down with her imported frock in a very wet puddle, till a gentleman, not really knowing what it was all about, reached a helping hand and drew her, spluttering and resisting, back against the wall.

Somebody took pity on the poor lady and hustled her off to a car and to her home, and the crowd soon dispersed. But Lisle Kingsley, following her mother across the street, gave one more glance back at the blue-eyed boy as she turned away, her own smile still on her lips. She felt somehow that they were friends, she and that young man, and the thought of him lingered with her as she went on her way.

John Sargent, as he turned and looked after her furtively, wondered if he would ever see that girl again. He felt a warm, friendly comfort from her smile on a day that had started in anything but a pleasant way.

Then suddenly he heard the words of the two men working next to him. They had paused in their work and were gazing after the girl.

“That’s old Kingsley’s kid,” one of them said, the lowering one who had been so disagreeable to Mrs. Gately.

“Say, is that right?” asked the other one of those who had assisted in the mud slinging. “She’s some looker all right! You didn’t hear hermaking a fuss about the mud, either, and I bet she has as many ‘imported’ shoes and ‘fwocks’ as the old dame.”

He twisted his face and his voice into a clever imitation of Mrs. Gately’s expressions and tones, and the rest of the gang laughed roughly and cast appraising glances after the pretty girl who was skirting the wet places and crossing the road.

So, that was who she was, thought John Sargent. Daughter of a very rich man! He had heard of him. He turned a furtive look over his shoulder and took in with a swift glance the sign that glittered goldenly in the morning sunshine over the office door just beyond where he was working. He caught a glimpse of the tall gentleman entering the doorway. That would be the girl’s father. He looked it every inch. Dignity, culture, keenness, distinction. All the attributes that go to make up success in the world today. Then, without seeming to do so, his eyes swept across the street to where he could watch the girl as she walked. She was graceful, slender, with an air of ease and assurance without arrogance. The kind of daughter a father like that man would be expected to have. And she had smiled at him and understood how he was feeling about that silly woman! He would cherish that smile. He probably would never see her again, but she would be pleasant to think about now and then, a sort of ideal.

Lisle crossed the street back to her father’s office just above where the water break had been. A slight rise in the ground at that point had left the crossing dry. She came down the street and went in the front office door. That seemed to settle it in John Sargent’s mind that she was the daughter of the head of that well-known and distinguished firm.

And while John Sargent was musing on this matter, the man Lacey stood not far away on the sidewalk, studying him.

As it happened there was still quite a crowd standing around and Lacey was in no danger of being observed, for many people lingered there, watching the work that was going on, and he was not noticeable. As he stood on the sidewalk and looked around quite casually, he noticed his handyman Kurt Entry standing across from him watching the workers interestedly. The other man did not look at him, and no recognition passed between them. But that, of course, was as it should be. And this was not the first time that such a thing had happened, when other operations of the same sort were being planned. Kurt Entry was well trained, a good actor. He knew how to erase himself from any given picture. That was why he was hired.

But the man Lacey carried away with him was the picture of the young man with the gold hair and the blue eyes above the shirt. Yes, that was a young man who would have good sense, but wasn’t there something lacking in that face for the job they wanted to wish on him? Did he lack the daredevil glint in his eye, or didn’t he? There was something firm and determined about the set of his lips, and once won over to accept the role that he was offered, he would stick. He would be a faithful emissary. But would he accept? There was a keen look in his eye. He wouldn’t be one to be fooled, to accept a job without understanding what it involved. Still, with a sick grandmother—a funeral perhaps in the offing—money might be an inducement. It would take plenty, of course, if there proved to be a hereditary fanaticism to be overcome, but money would likely do it. An overzealous twist in the brain would be the only thing that might prevent it. Still, he looked a merry sort of lad with a good sense of humor, and not every fanatic had a sense of humor. Perhaps it would be as well to send Kurt after him tomorrow and let him sound him out about a better-paying job.

Lacey was back in his room a good half hour before the expected phone call came.

“Well, Lacey, size yer man up?” came the boss’s sneering voice.

“Yeah. I looked him over. He may be all right, but he looks mighty soft to me.”

“You’re mistaken. Nothing soft about him. I’ve been watching him for several months. Got a lot of character, that kid.”

“Well, mebbe so, but the girl I’m thinking of is a regular. If you had time I could tell you a lot of jobs that dame’s pulled off, and she’s pretty as all git out. If I know anything at all about that young guy you say is to have charge of his dad’s plant, she could work him for almost anything you want. Like to have you see her. She’s worth looking at. If you could drop in anywhere you want to suggest, I could have her there and introduce you. You wouldn’t need to commit yourself in her presence. She knows the score.”

“You haven’t told her anything about this affair, have you?”

“What do you take me for? I should say not. But I’ve tried her out already on so many other jobs, I know just how she’ll react, and this would be right up her alley. She’d eat it up. She’s plenty proud of her past record.”

“I see,” said the grim, heavy voice of the boss. “But I tell you, this is no lady’s job. It wouldn’t be permitted.”

“Okay! But I’d like you to meet the lady now she’s in the vicinity. You’ll need her sometime, even if you don’t need her now.”

“Well,” said Weaver after an instant’s pause, “I’ll be at the restaurant at the corner of Tenth and Harper at twelve sharp tomorrow. If she’s there, all right, and if not, that’s the end. This, you understand, is a man’s job. Get to work on your man as soon as possible. I’ll have the job rounded up for him by morning. That’s all!” And the boss hung up.

But about that time Kurt Entry lurched across the pile of rubble at the curb and fell into step behind the young man John Sargent, whom he had been watching carefully for the last hour.

And a little later a girl in a grubby room of a cheap hotel received a phone call.

“That you, Erda?”

“The same.”

“We’ll make it twelve sharp tomorrow. Tenth and Harper.”

“Very well. Any special line?”

“Nothing new yet.”

“Okay!”

Chapter 2

Lisle went through the outer room where stenographers and clerks were already hard at work. She smiled at one and another of them, and they all smiled back as if they liked her. She had a habit of making even a smile seem an honor.

Lisle had not long to wait. Her mother soon came out of her father’s inner office, and they started out together on their shopping expedition.

“I think we had better go to the tailor’s first, dear, and get that fitting out of the way, don’t you?” said her mother. “There may be some changes to make, and I don’t want him to be held up getting your suit done. You might need it in a hurry. There is liable to be a change in the weather any time now. Also, you will have to decide on the fur for your collar, you know. Really, I think, dear, that it is smarter to have fur on your collar this year, don’t you? It’s a bit more feminine, and I don’t want you to look as if you were in uniform, not all the time, anyway. You’re too young to affect that style.”

“Yes, I like the fur, Mother. It’s certainly more comfortable in the fall before it’s time to put on a whole fur coat. But there isn’t any special hurry about it, is there? I thought you wanted to see those gloves that were advertised in the paper this morning, and they might be all gone if we don’t go to Hayden’s first.”

“That’s true, too, but after all, there are always gloves of one kind or another. I think we ought to get this fitting out of the way at once. You see, Victor telephoned after you went down to the car to say he would meet us at Hayden’s for lunch at noon. We must get there soon after twelve so we could go to lunch together.”

“Oh!” said Lisle, a kind of blank dismay in her voice. “I thought this was going to be a shopping excursion. Why did he have to barge in? I do hate to have to select things with somebody standing around watching, criticizing, trying to advise. It always upsets my judgment and I take anything, whether I like it or not. Victor always thinks he knows it all and insists that I do as he suggests.”

Her mother looked at her in surprise.

“Why, my dear! I didn’t know you felt that way. He asked if he might come, and I supposed, of course, that it would be the thing you would want, especially since he may receive his commission as an officer any day now and will probably soon be called away. I couldn’t say no, he seemed so eager about it. I didn’t think you would want to be rude to him.”

“Of course not, Mother. I just thought it would be so nice to have the whole day to ourselves and not have to hurry. But it’s quite all right. Of course you were right to tell him to come.”

Her mother gave her a quick look, noted her troubled face—the slight frown on the girl’s soft brows, the disappointed set of the sweet lips—and then her tone changed.

“Lisle, have you and Victor been having a—difference of opinion? Not a quarrel, of course. I am sure you would not descend to anything as unladylike as that, but has something come between you? I noticed you have not been going out with him every time he’s asked you.” She watched her daughter’s face while she waited for an answer.

“Why, no, Mother, not exactly a difference of opinion,” said Lisle, “but he has been sort of disappointing lately. I suppose maybe he’s just growing up, but he was a lot nicer the way he used to be.”

“Why, my dear!” said her mother. “I had no idea you felt that way. What has he done? What happened?”

“Oh, nothing, Mother! Nothing really happened. He just seems so determined that he is going to order my life for me.”

“But—my child! In what way?”

“Well, for one thing, he doesn’t like my college. He says I need to get away from home, that I’m living in a very narrow environment, and I didn’t like that! I don’t think he has any right to criticize the way you and Father are bringing me up. He keeps saying I have no mind of my own. And I do! I like my college, and I don’t want to go to any other. I refuse to go to any highbrow college, just to be able to say I’ve been there. I prefer the way you chose for me to be educated.”

“That’s very sweet of you, dear, and certainly we do not need any advice in arranging for your education. Your father and I have talked this matter over for several years, and we felt that on the whole we had chosen well and wisely. Also, we wanted to keep you near us as long as possible, and I still think that was right. But surely, Lisle, there is some mistake. It does not seem like the old Victor to criticize your family and your life plans. You must have misunderstood him. He must have been joking. Just doing what you call ‘kidding.’ He couldn’t have meant that. He was well brought up. His mother is very particular about behavior. He was taught to be polite almost from his babyhood!”

“Oh, he’s polite enough,” said Lisle thoughtfully. And then after an instant’s pause, “But very firm!”

Her mother studied her with a puzzled expression.

“What do you mean by that, dear?”

“He’s determined I shall think for myself, even if I do make mistakes, and not always have to consider what you would say or think about anything.”

“My dear, do you feel the need of more freedom in your actions?” asked the mother with a troubled look.

“No, Mother, I don’t,” said Lisle with a set of her firm little chin. “I’ve always sort of gloried in the fact that you and father never said ‘You shall’ or ‘You must,’ not since I was a very little child and very naughty. You’ve always taken me to a quiet place and explained why you felt it would not be a good thing to do, and then put it up to me to decide. And I couldn’t help but see that your advice was good. You gave me the feeling that you had had more experience than I, and you had found it wasn’t a good thing to do. You gave me confidence in your judgment. It was as if we were going down a strange road together, and you had traveled that way before and found where it led and where to turn off, and if I saw a side road where a lot of flowers grew and you said it led to a swamp where I might get drowned quickly and no one would know where I was, you taught me to think twice about it, and to remember what your experience had been when you took that same path years ago and almost lost your life.”

A look of great relief passed over the quiet dignity of the mother’s face. Then after a moment she asked, “And couldn’t you explain it that way to Victor?”

The girl’s face was swept by a stormy memory.

“I have, Mother. I told it to him just like that, and he simply got that maddening smile on his face, a sort of superior sneer he has, and said, ‘Times have changed, darling, and you are living in the antique past!’ ”

The mother looked startled.

“Well,” she said, “I’m afraid I shouldn’t at all approve of the college he attends. It seems to have done something undesirable to him. However, my dear, I suppose it is just a phase of his youth. He will probably get over it when he really grows up and gets beyond that superiority complex. That’s what your father feared when he heard Victor had chosen that college. They simply don’t believe anything. But I’m sure he’ll get over that.”

“I don’t think he will, Mother,” said Lisle sadly. “He really is grown up, you know. He’ll be of age in a few days now. You know that party his mother is giving is in honor of his twenty-first birthday. Mother, I wish I didn’t have to go to that! I don’t like his attitude toward me. It’s entirely too possessive.”

“Well, dear child, don’t worry about that. There may not be any party. Not if he goes to war and is called soon. But of course you would have to go if there is a party. You are one of his oldest friends, and you are already invited.”

“What do you mean, there may not be any party? Of course there’ll be a party.”

“Why, Victor told me he wasn’t sure, but he might have to go away sooner than he expected. He had a letter this morning hinting that he might be called very soon.” Mrs. Kingsley was watching her daughter closely. How would this news affect her child? But Lisle did not wince, did not turn pale, did not even look disturbed.

“Of course, Mother, that would be entirely possible, I had thought of that, and almost dared to hope that that might be a way of escape from that party, but it seems so selfish to want it just for my own comfort, when I know Victor is looking forward to it, and I know it means so much to his mother. But you know, Mother, there isn’t a chance that even that possibility would stop that party. Why, Victor’s mother has been looking forward to that party and counting on it for years, and she’ll find some way to pull it off in spite of the government. You’ll see. I’ve heard her talk so many times, and she’s simply fed it to Victor all through the years. You’d almost think it was some kind of coronation day. And he’s begun to act as if he felt that way about it himself. He has, Mother. It just made me ashamed for him when he began to talk the other day.”

“But Lisle! Child! Don’t speak so bitterly! I can’t think how you can turn against your old friend this way. Victor is not to blame. That party is a sort of symbol of his young manhood. Perhaps his mother has been foolish about it. She’s rather fond of social customs and old family traditions. But you ought not to turn against your old friend for that.”

“Oh, I haven’t turned against him, Mother, only it makes me so tired to hear them talk. Why, they are making a lot more of that party than they are of Victor’s going off to war.”

“Well, dear, perhaps it’s something to help ease the pain of their parting. You know Mrs. Vandingham has always been so very close to her son.”

“Yes, I know,” said Lisle. “But that’s no excuse for her making a perfect sissy out of him.”

“Oh, my dear! What a state of mind you are in! You never thought that of Victor before, I’m sure.”

“No … perhaps not!” said the girl with a troubled sigh. “Though I’m not sure but it was in the back of my mind all the time, and sometimes it would come up and worry me.”

“Oh, my dear! Why didn’t you tell me? Perhaps we could have done something about it.”

“What could we have done? Besides, I wasn’t altogether sure about anything.”

“Well, at least we could have talked it over and sifted your feeling down to facts. And yes, perhaps we could have done something really practical about it. Victor always used to be amenable to reason. Perhaps he has had no one to talk things over with him. You know his mother is very conservative and dislikes to bring personal matters out into the open. When Victor was a little child I can remember her saying that it was better not to notice naughty things that he did. He would be more likely to drop them if they were not mentioned.”

“Yes, I know. He never talks things over with his mother. He thinks women have the wrong viewpoints on almost everything and they are not wise advisers of the male sex. That’s what he said, Mother! Just recently. He never used to talk that way, but now he says he thinks women were made principally to be petted and to make a pleasant home for men. And for his father, he’s too busy to talk anything over with him. Don’t you see, Mother? That’s what is the matter with Victor. He’s made his own philosophy of life and he means to live by it. He says they encourage the students at his college to do just that. He told me so the other day, and he said that if girls were brought up that way they wouldn’t be so feminine in their ways. But he said he liked them better feminine, that he couldn’t bear a woman who was always trying to make him over. And since he said that, Mother, I haven’t tried to talk anything over with him. It wasn’t any use.”

“Well,” sighed her mother, “I’m just sorry you didn’t mention this before. I would have had a good talk with him. He always used to listen most respectfully to anything I said. Maybe it’s not too late yet.”

“I think it is, Mother. Victor is very definite in his ‘philosophy of life’ as he calls it. Just wait till you hear him talk. He simply thinks he knows it all, and I’d hate to have him try to take you down, and show you where he thinks you belong, the way he did to me. I would just hate him if he tried it, Mother.”

“Well,” said the mother with a sigh, “I certainly hope that time will prove you are mistaken. I was always very fond of Victor, and I thought your friendship with him was such a happy, healthy companionship. I would be sorry indeed to have it turn out the way you seem to think it has. But don’t be too hasty in your judgment. Remember you have been separated for almost a year now, and it would be natural there would be some changes. But those things will probably all be adjusted as time goes on and life falls into its normal lines again. Try not to think too much about it. Just let things work out. Be your old self as far as possible. Avoid discussions, and above all wrangling, even about things that matter. You can state your own belief, of course, when necessary, but let it go at that. Don’t try to argue. Half his arguments will die out if he has no opposition, I imagine. Now dear, here we are! Forget all this and put your mind on your suit. I want you to be sure you get the right fur on that coat, because I do dislike to have you uncertain about things you have to wear through a season or two. This is the time to select wisely. Especially now as a war measure, you know. It isn’t patriotic to buy carelessly and fling a thing aside because you are tired of it, and get another. You know we are constantly warned about that. There! See the coat in the window! Do you like that shade of brown fur? I think that would be becoming to you, don’t you?”

So they entered the tailor’s shop and were at once immersed in thoughts of garments.

But now and again, back in the recesses of her mind, Lisle caught herself regretting that Victor was to be at lunch with them. Somehow she couldn’t seem to get away from annoying thoughts.