0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

A hunted man's sister and his beloved join together in a desperate fight to try to prove his innocence... but time is running out!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

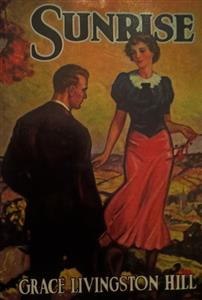

Sunrise

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1937

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

At half past ten on Wednesday morning young Jason Whitney came out of the bank and walked down Main Street in the opposite direction from his home with a hard set look upon his face.

By eleven fifteen through some mysterious grapevine every boy on Main Street knew that Jason Whitney had lost his job in the bank and had disappeared down the highway toward the east.

When the noon whistle blew at the sawmill Charles Parsons drove up to the bank, got out of his old-fashioned car, and went into the bank to cash a check; when he drove home his brows were puckered thoughtfully. He parked his car in the garage and went into the kitchen. His wife Hannah was preparing a nice lunch, ham and fried potatoes and a big thin slice of a mild raw onion on a lettuce leaf with slivers of green peppers and a pleasant tangy dressing.

He washed his hands at the sink in the kitchen, though they had a bathroom on the first floor as well as the second. He had always done that, and somehow the bathrooms had not been able to change his habits. Hannah never bothered him about it. She liked to see him contented, and she enjoyed her two bathrooms in a sweet content herself and kept them fit for kings and queens.

“Where is Rowan?” asked the young man’s father as he sat down at the table.

“He went over to Bainbridge to see about exchanging his car for one he’s heard of over there. He thinks this one is going to be an expense to him pretty soon,” explained Rowan’s mother.

“Anybody go with him?” asked the father sharply.

Hannah shook her head.

“No, he said he wanted to go alone. I suggested that Mrs. Morton might like to go to see her daughter, but he said no, he didn’t want to be bothered. He wanted to be alone when he decided about the car.”

Charles looked at his wife thoughtfully.

“You’re sure he didn’t pick up Jason Whitney somewhere?”

“Why, of course not, Charles. Jason Whitney works in the bank and would be at work in the morning.”

“Jason Whitney doesn’t work in the bank anymore!”

“Charles! You don’t mean he’s quit?”

“No, he was fired!”

“What for?” said Hannah, aghast.

“I don’t know. I didn’t ask, but nobody seems to know or I’m sure I would have been told. Everybody downtown is agog to tell everything they can, and make up the rest, but they didn’t have any reason to offer. Of course there’ll be plenty of hearsay by night. But anyway, even if Jason Whitney hadn’t been fired, I wouldn’t put it past him to take a day off if he wanted to. What time did Rowan leave?”

“Half past eight. But it isn’t like you, Charles, to be so hard on Jason. He’s only a boy you know, younger by two years than Rowan.”

“He’s old enough to know better than most of the things he does,” said Charles shutting his lips together with a snap. “And I don’t like to see our Rowan traveling with him continually.”

“Now, Charles, you don’t think a mere boy like that can hurt our Rowan!”

“Nobody’s beyond hurting. Those things are subtle! Unconscious influence is sometimes the worst influence of all. It undermines faith! And, Hannah, I don’t see Rowan going to church quite as regularly as he used to. Last Sunday morning, do you know where he was?”

“No,” said Hannah with an undisturbed look in her eyes.

“Well, I do,” said Charles sharply. “He was walking east on the highway with Jason Whitney, down toward that disreputable Rowley joint, and if our son has taken to playing pool and drinking on Sunday morning with that worthless Jason Whitney instead of going to church I’ll find a way to stop it or I’ll disown him!”

“Charles! You know you wouldn’t do that! Even God doesn’t do that! Not to His real own children!”

Charles’ face softened almost imperceptibly.

“Well, I don’t expect it’ll come to that, of course,” he said firmly. “I expect to be able to stop this nonsense without any such strenuous methods. But I’ve got my eyes open and I’m not letting anything like that go by again!”

“Charles, remember he’s over twenty-one! You wouldn’t have stood any such high-handedness when you were his age. He’s a lot like you, you know.”

“I’ll remember, Hannah, but I intend to stop his tagging around with Jason Whitney!”

Hannah was still for a minute, watching the firm set of her husband’s lips, then she spoke again, this time very gently.

“I guess you know why he does it, don’t you?”

Charles looked up sharply.

“Does what?”

“Goes around with Jason Whitney. You know why he does it, don’t you?”

“Well, why?” His tone bore a hint of impatience.

“For Jason’s sister’s sake.”

“Well, that’s no reason at all! If Rowan isn’t man enough to win a girl without tagging around with her spoiled baby-brother he’d better lose her. Joyce Whitney is all right. She’s a sweet girl, and I’d like to see our boy marry her, if she’ll have him, when he gets a little more stable, but I don’t see his companioning with Jason. Joyce can’t help what her brother is, I suppose, but a man doesn’t have to marry all a girl’s relations.”

“You married mine!” said Hannah quietly. “Look at Cousin Ephraim, how you’ve been patient with him, and helped him out of the very gutter, time and again.”

“Oh, well—!” said Charles impatiently, “that was different!”

“How was it different? And Charles, you must remember Joyce loves her brother. Her mother left him in her care when she died.”

“Well, why didn’t she bring him up right then?” snorted Charles.

“Now, Charles, you know she was barely a child herself, and after the second Mrs. Whitney came she hadn’t a chance. She packed them both off to school. And you know what Jason’s father is, Charles. Hard! That’s what he is. Jason hasn’t ever had any love nor trust such as we’ve given Rowan. Jason hasn’t had half a chance!”

“Well, that may all be true,” said Charles looking a bit ashamed, “but that’s no reason why our boy should go wrong in consequence.”

“I don’t believe he did!” said Hannah determinedly. “I don’t believe he was playing pool nor drinking on Sunday morning! I don’t believe he even went into that Rowley place unless it was to drag Jason out!”

“Well, mebbe I don’t either,” owned Charles, “but I mean to do more than just believe. I mean to know! It’s my business as a father to know.”

“Well—I know!” said Hannah firmly.

Charles looked at her with understanding in his eyes. Then he came over and stooped his tall height to kiss her forehead.

“Good little mother!” he murmured, like a benediction.

The news reached the Whitney home, a big old-fashioned white farmhouse on the outskirts of town, about half past twelve, when the grocery boy delivered some orders that had been telephoned.

“Seen Jason anywhere? It’s high time he was here ta lunch!” asked Aunt Libby, an elderly white woman whom the second Mrs. Whitney had rescued from the poorhouse and put to work in her kitchen. Some of the neighbors wondered if it might not have been easier for Aunt Libby if she had stayed in the poorhouse.

“Yeah. I seen him ’bout two hours ago walkin’ down the pike toward Rowley’s”

“Aw, he wouldn’t a ben walkin’ down thetaway in the middle of the mornin’,” said Aunt Libby proudly. “Jason works in the bank now.”

“No, he don’t! Not no more!” imparted the grocery boy. “He got fired this mornin’. Didn’t ya know?”

“Aw, get away with yer kiddin’!” snapped Aunt Libby loftily, and vanished down to the cellar with her arms full of fruit jars.

Nevertheless her eyes were anxious as she came in to place the hot dishes on the table and ring the lunch bell.

“Where’s Jason?” asked his stepmother grimly turning her small sharp eyes to the window and looking down the road. “Are they keeping him again at the bank? I’ll have to phone them. I can’t have my meal hours upset this way. It gives me indigestion.” She walked heavily over to the telephone.

Aunt Libby gave a frightened glance toward Joyce who was just coming in the room and tried to speak so that she would not hear, but Joyce’s ears were sharp, and she heard every word.

“Sammy Rounds from the grocery says he got fired this morning!”

Jason’s stepmother set the phone down hard on the table where it lived and whirled around as if the matter were some fault of Aunt Libby’s.

“Exactly what I thought would happen!” she charged, fixing the cringing woman with a cold steel eye. “But you should never allow the help from the grocery to gossip to you about the family for which you work.”

“I didn’t—I just ast him ef he’d seen Jason—!” quavered Aunt Libby.

“Exactly what I say. Gossiping with the help from the grocery!” thundered Mrs. Whitney. “Don’t do it again! That’ll do! We’ll server ourselves today. You may go to the kitchen.”

Aunt Libby went meekly out with anxious tears slipping weakly down her withered cheeks. She was fond of Jason. She slipped him cookies on the sly when he was late to meals and would have lost out on food according to his stepmother. Sometimes she even dared to make chocolate cake when it wasn’t ordered, always revealing her wickedness when the senior Mr. Whitney was present because she knew he liked chocolate cake, and Mrs. Whitney wouldn’t dare reprove her for it in front of him.

When the kitchen door was shut Mrs. Whitney turned toward Jason’s sister:

“Well,” she said ominously, “the fully expected has come to pass! Your darling brother has been dismissed from the bank! I was sure it would happen!”

“Don’t you think we had better wait until we hear Jason’s version? The grocery boy may not know anything about it. It may not be true!” said Joyce trying to appear unconcerned, although her face was white with anxiety.

“Jason’s version!” laughed the stepmother contemptuously, “that’s it! That’s always it! Listen to Jason’s version! And of course Jason’s version is perfectly smooth. Well, you know what your father will say to Jason when he comes home.”

“Perhaps,” said Joyce, a wild fear in her eyes, and a quaver in her voice, “perhaps he won’t come home!”

“Ha!” sneered Mrs. Whitney contemptuously. “Not he! He’ll come home all right. He loves his ease too much to leave home. Where would he get his bread and butter? I declare if I had my way your father would send him packing. It’s high time he did something to prove he is a man. You’ve spoiled him outrageously, Joyce. Always helping him to hide things from his father, always using your own pocket money to pay his debts. If you keep that up I’m going to advise your father not to let you have spending money. You’ll have to learn that your brother isn’t a little darling child any longer for you to moon over. He’s a wild irresponsible young man, trailing off with all sorts, gambling away what little money his father dares give him, and drinking with a lot of lowdown gangsters. I declare I’m ashamed to go among my friends any more, the things they find to tell me about my stepson.”

“Do you discuss Jason with your friends?” asked Joyce in a stricken voice.

“How can I help it?” declared the woman in a raucous voice. “They force it upon me, pitying me, and laughing about his sins, trying to make light of them!”

Joyce was very white, and was gripping her hands together to keep them from shaking.

“But—I thought—!” large tears came into her eyes and she struggled to keep them back. She turned away quickly to hide them before they should fall.

“Well, you thought what?”

“You—were just reproving Aunt Libby for even hearing something she couldn’t help hearing.”

“She’s a servant! That’s not at all the same thing. Besides, are you presuming to dictate to me? To criticize me? Sit down and eat your lunch. There’s no need in stretching out the meal to last the day. I want Aunt Libby to clean the silver this afternoon. And if Jason doesn’t come till after we’re done he goes lunchless till supper! Do you understand? No slipping him choice morsels on the side. I’m not going to have Jason upset everything for me any longer. I’ve stood enough from him, and if he’s determined to be a disgrace to the family, very well, let him stand a few things himself! Sit down!”

Joyce struggled with her anger and her tears and sat down. It seemed a physical impossibility to eat, but there was no advantage in openly flouting her stepmother. She had tried it before and only made matters worse.

Mrs. Whitney, unhindered by responses from Joyce, went back to her favorite theme, which today she was pleased to call “Jason’s Version,” and harped on it. She rehashed everything that Jason had done, good or bad, and scourged them equally, until at last poor Joyce rose from the table in desperation:

“If you had only tried to make Jason a little happy sometimes,” she protested with a sob, “perhaps he might not have been so unsatisfactory.”

“Happy!” snorted Mrs. Whitney. “Happy! Make that young scapegrace happy? I wonder how you would have me go about it. Set up a pool table in my parlor, and invite a lot of gangsters here? Let them slop beer all over my furniture and call in a mob of girls from the street to dance with him? That’s his idea of happiness, and I’m sure I—”

But Joyce had hurried up to her own room, shut the door, and flung herself upon her knees beside her bed, sobbing as if her heart would break.

About that time Rose Allison, shy pretty daughter of the minister, received a telephone call from Jason Whitney.

They had been classmates together in high school, though never very close. Just the day before, however, they had met on the street, Rose in a new pink dress that gave her a willowy grace, and threw a soft glow upon her rounded cheeks. Jason had paused to lift his hat on his way to the bank. He had always liked Rose. She looked up shyly, and then because there seemed nothing more to say beyond good morning, Jason made as if to move on. Suddenly Rose lifted her earnest blue eyes and spoke hurriedly:

“Oh, Jason, I wish you’d do something for me!” There was something so wistful about her eyes, and she seemed so young and sweet, Jason was touched.

“Sure, I will, kid, what is it?” he answered without hesitation, thrilled in spite of himself that she should ask him.

“Why, you see we have a meeting at our church tomorrow night, and each of us pledged to get ten people to come. I’ve tried as hard as I can and I can only get nine. Would you be my tenth?”

“Great Caesar’s ghost, Rose! Church?Me? I never go to church! It isn’t my line.”

“I know,” she said a little sadly, “I wish you did. I often wonder why you don’t. We have pleasant times in church. But couldn’t you come this once? I don’t know another soul to ask.”

“What is it?” he asked, hedging, trying to think of some good excuse. “Just prayer meeting?”

“No,” said Rose eagerly, “it’s in the church, not the prayer meeting room, and they’ve got a wonderful speaker from the city. He sings, too. My cousin heard him and she says he’s wonderful. Says he’s a man’s man. I think you would like him.”

Jason stood there in the sunshine looking down at her beautiful face and something melted in his heart. He had an impulse to try and keep that smile on her face and that light in her eyes, and before he realized what he was going to do he had said:

“Sure, kid, I’ll do it! If you want it so much, I’ll be there! What time? Eight? I’ll be there!” and the great light that blazed in her face thrilled his heart again and made him wonder as he went his way. Rose Allison! Who knew she was like that? And a faint wistfulness passed over his own soul. Suppose he had been different. Suppose he had gone to Sunday school and church and grown up in the society of the young people of the church, and been a companion of a girl like that! Suppose he had a right to take her places, and send her flowers and candy! Would that in any way satisfy the great restlessness and craving that stirred his soul from day to day, prodding him to first one depredation or transgression and then another, without so far any adequate return?

Well, this once he would keep his word to her and go, even if it was dry as dust. Of course he wouldn’t find anything interesting in church. But he would go and watch her from afar and try to figure out why she had asked him. Was it just what she had said, that she wanted so many scalps to hang at her belt when the prayer meeting reckoning came, or had there been some faint personal interest in himself?

He thought about that as he walked on to the bank and the idea was not unpleasant. There had been something in her look, in her smile that had seemed warm and friendly, almost as if she liked him, when she had asked him. And that lovely flush that came in her cheeks as she raised her long lashes and looked up pleadingly at him! His heart thrilled again. At that moment he couldn’t remember that anybody, except his sister Joyce, had ever taken a personal interest in him. Not any girl had ever looked at him like that. Oh, there had been girls, girls looking archly, girls all painted up, and trying to be as blasé as the boys, girls with hidden meanings in their glances, girls that stirred the worst in him. But never a girl with a guileless look like this, a look of real friendly liking, too, that she was neither trying to conceal nor use to attract him. And he liked it. It sent a sweet keen pain through his heart, and made him wish he were worthy of a look like that. Of course he wasn’t, but it wouldn’t do any harm to please her this once anyway.

When he called up, Rose hadn’t any idea where he was calling from, and her heart gave a little flutter. He hadn’t forgotten all about her then. He was probably going to make some excuse, but anyway, he had remembered.

“Is that you, Rose?” His voice sounded manly and respectful. “Say, kid, I can’t keep my promise to you after all. I meant to. Honest I did! But a little something happened at the bank today and I’m leaving, see?”

“Oh! Jason! I’m sorry!” Her voice full of genuine dismay. “You—haven’t—done anything—to make them—?” Her voice trailed off fearsomely.

“No, not that, Rose! That’s the truth! I haven’t done a thing! But the poor fishes think I have, and that’s just as bad. And the worst of it is I can’t tell what I know, and so they’ve pinned it on me. Now you’ll probably hear to the contrary, but that’s the truth. You can believe it or not. I can’t blame you if you don’t”

“I believe you, Jason!” said the grave sweet voice of the girl. “I’ll always believe you!” She said it as if it were a vow.

“Thanks a lot!” said Jason struggling with a lump in his throat. “And I’ll always tell you the truth!” he answered back. “That is—” he added, “if I ever see you again! I’m beating it, kid! I’m not sure I’ll ever come back!”

“Ohh—Jason!” There were almost tears in the voice. “Please don’t do that! Please stay at home and clear things up!”

“I can’t, kid, they won’t clear up for me, ever, I guess. Not here anyway! I can’t get a square deal! And nobody cares, except my sister. Not anybody!”

“I care!” said Rose suddenly, almost unexpectedly to herself. There was a sweet dignity in her words. “I care, and I believe you!”

Jason’s voice husked with sudden tears:

“Thanks awfully, a lot, Rose!” His own voice was serious and earnest. “I’ll not forget you said that. I’ll never forget you cared and you believed me! Sometime maybe I’ll turn out to be something after all, just for that! And I’m mighty sorry I can’t keep my promise to you tonight! I meant to, I really did. You didn’t think I did, but I did! But I’ll be thinking of you tonight! I’ll be all alone and I’ll be thinking of you. And if the time ever comes when I’m fit to come back, I’ll let you know. Maybe sometime I’ll let you know anyway. I’ll think a lot about you, kid. Good-bye—Rose—!”

Rose turned away from the telephone with her eyes full of tears and went up to her room, and another girl went down on her knees beside her bed to pray for Jason.

At six o’clock the minister came home to supper. There were baked potatoes, creamed codfish, baked sweet apples, and gingerbread. As he passed the butter to Rose he looked at her speculatively.

“By the way, Rosie, didn’t you go to school with Jason Whitney?”

Rose’s face flamed suddenly and then grew white. She rose precipitately and took the bread plate to refill it, saying as she went into the kitchen, “Yes, Father.”

When Rose came back with the bread plate her hand was trembling but she managed to set the plate down without being noticed, and slipped into her seat again. Her mother was busy with the younger children and did not notice how white her face was.

“Well, he seems to be in trouble again,” said her father, as he scooped out his baked potato and put butter on it.

“Trouble?” asked Rose, trying not to seem too interested.

“Yes, they tell me he’s been dismissed from the bank. It does seem too bad for his sister’s sake at least. She is so fond of him, and so worried about him! But I’m afraid he is worthless. Or, perhaps I had better say, weak. He will go in bad company. And he’s innately an idler. How was he in school? Do you remember?”

Rose looked down at her plate thoughtfully, trying to think back, remembering painfully instances in which Jason had been disciplined.

“Why, I always thought he was a great deal misunderstood,” she said at last. “If anything wrong was done the teachers just naturally blamed it on him, and several times I happened to know Corey Watkins was really the one who did it.”

“Corey Watkins? Why, I thought he was the most exemplary boy! I always heard him spoken of in that way.”

“You would. He was slick! He’d put the other fellows up to things and then he’d look so smug! I used to wish sometimes the teacher had a chance to sit down where I did!”

“Well, that’s interesting! So you thought Jason Whitney was misunderstood. You thought he was a pretty good boy, did you?” The minister was studying his young daughter’s face interestedly.

Rose looked down at her plate thoughtfully, and then she lifted her eyes boldly.

“No, Father, he wasn’t always good. He did a lot of things, things that were against rules, you know, and all that. But he never did mean things like some of the other boys; like putting a hornet in the teacher’s desk so she would get stung on her nose; or like putting a little garter snake in her lunch basket. He did fix a hat in the window over her head once where it would fall on her head during class and make everybody laugh, and he drew a funny picture of her on the blackboard the time she fell down in a mud puddle. He got blamed for the snake, and the hornet, and for breaking up Tommy Beldon’s bicycle that Rich Howland threw over the bridge, and even for stealing the money for the teacher’s Christmas present, but they never did find out who threw the hat down on her head, nor even who drew the picture on the blackboard.”

The minister grinned appreciatively.

“Well, but didn’t they find out eventually that Jason hadn’t stolen the money, or broken the bicycle? Surely he defended himself.”

“No, he didn’t!” said Rose. “I asked him once why he didn’t tell the teacher he didn’t do it, and he just looked glum and said if they wanted to think such rotten things about him they could. He wasn’t going to tell them differently. So—I—well I went and told the teacher! But she wouldn’t believe me. She told me girls had no way of finding out those things. She said a nice girl didn’t know what boys like Jason would do, and that I mustn’t try to defend him when the whole school board had investigated and said he did it. She said people would think I had a crush on him.”

Rose’s cheeks were very red now, and her father looked at her in astonishment.

“You don’t say! I didn’t suppose you ever looked twice at the boy. You never told us anything about it.”

“I didn’t think it was anything you’d especially care about,” said Rose, suddenly realizing that she had been speaking out of the depths of her heart.

The minister studied her a moment in silence and then he said:

“Well, I’m sure I’m very glad to hear it; Jason had a very nice mother, and his sister is a rare girl. Perhaps he has been misunderstood in some directions. I know his father is a rather hard man. But it’s a pity Jason doesn’t go in better company.”

Rose gave attention to her dinner and said no more, but her father watched her thoughtfully for some minutes and decided that he would try to get to know Jason Whitney and see if his child was right in her judgements.

“Doesn’t Corey Watkins work in the bank, too?” he suddenly asked. Rose looked up startled, remembering what Jason had said over the telephone. “Why, yes!” she said with troubled wonder. Then she started to say more but thought better of it. That talk on the telephone had been something confidential. She couldn’t bring herself to mention it even to her beloved father. Not now, anyway. But she sat by the window for a long time in the darkness that night, thinking about Jason and wondering if Corey Watkins had anything to do with his dismissal from the bank.

When Jason didn’t come home to supper that night Joyce excused herself from eating, saying she had a headache, and Mrs. Whitney gave her husband, newly returned from a business trip to New York, a lecture on training his son. Joyce could hear their loud voices arguing on what should have been done in the past and what ought to be done in the future, each blaming the other for the son’s failings, the father bitterly, the wife triumphantly. It wasn’t her fault. It was his and Joyce’s fault.

And she told him just what course he ought to pursue when Jason came home at midnight or later, probably drunk! Not that Jason had ever come home yet in that condition, though he had often brought a smell of liquor on his breath. But she was assuming that anything goes now that Jason had allowed himself to lose his job at the bank. Such a nice job! So respectable, and so in keeping with the family traditions! That was the final note of the tempest—a wail!

Then Joyce, even in her far bedroom, could hear her father at the telephone, storming at the president of the bank, denouncing him and all the Board of Trustees. Then bitterly denouncing his son, coming even to the threat of disowning him as a good-for-nothing. It was all very terrible to Joyce who had wept most of the afternoon, watching constantly out the window down the road for the brother who did not come. The little brother who had been put in her childish care! Her head was aching and she was both chilled and feverish. The rasping voice of her irritated father, the father whose nature and temper Jason had inherited, finally drove her from the house. She wandered down the old pasture out of sight of the house entirely, hovering near the edge of the wood in the shadow of the trees, sitting on a fallen log and watching the dying colors of the sunset in the west, and wishing sorrowfully that she and Jason might go home to God where Mother was and be out of it all.

She sat there until the crimson faded into purple, and the gold died out from the folds of purple and changed into thunder color, then soft pearly gray of luminous evening with a star set out to watch the shadows creep into night. And all around her the little creatures set up a symphony, crickets, and tree toads, and little stirring things, slipping away to their homes, and a far nightingale sang a sharp clear note above it all. Then an owl hooted tentatively over her head and took a preliminary curve or two above her, and it seemed that all things sad were in the sights and sounds. Night seemed to have claimed her life. Oh, God, will You not hear my prayer for Jason?

Over at the Parsons’ farm the house was dark later than usual. Joyce watched until she saw a light pierce through the darkness where their kitchen window must be, and then another in the dining room. It was not so far across the two pastures. But there was no light in the old barn that was now a garage. She had seen no car lights enter the Parsons’ driveway. Where was Rowan? Did he know what had come to Jason?

And over in the Parsons’ dining room Charles Parsons was sitting down to the table again and looking at the empty place where his son should be.

“Hasn’t Rowan got back from Bainbridge yet?” he asked with open worry in his voice.

“Not yet,” said Hannah, trying to keep her voice calm.

He was silent during the first part of the meal, trouble in his eyes.

“Jason hasn’t come home either,” he said significantly at last. “His stepmother telephoned down to the drugstore, just now while I was getting my evening paper, to know if he was there. She doesn’t hesitate to broadcast his absence.”

“No, she wouldn’t,” said Hannah quietly.

Nothing more was said until Charles finished his supper and shoved his chair back.

“I wish you’d tell Rowan I want him to wait up for me if I’m not here when he comes. This is Building Association night, you know, and I may be late.”

“You’ll be careful what you say to Rowan, Charles?”

“Yes, I’ll be careful!” And he stooped and kissed his gray-haired wife and patted her shoulder, a grave smile in his eyes as he went out.

Chapter 2

In the back room of Rowley’s place five men were eating an uninviting supper, waited upon by an ill-kempt woman with straggling gray hair and a sodden face. She was wearing men’s shoes and she shuffled noisily around the wooden floor as if driven by an unseen overseer.

Two of the men were young with hard daredevil faces. The others looked old in crime and had cruel mouths and eyes that flinched at nothing.

“Anything happened today, Nance?”

“Naw!”

“Nobody come in?”

“Cuppla parties fer gas. Nobody else, only ceptin’ Jase.”

“Jase ben here? Whad’d’ee want? He knowed we was away.”

“Didn’t want nuthin’. Jes’ come in ta make a phone call!”

Rowley dropped his knife harshly.

“Jase made a phone call here, an’ you didn’t tell me!”

“Well, I’m tellin’ ya now, ain’t I?”

Rowley frowned.

“Who’d’ee call?”

“Jes’ some gal. He was callin’ off a date.”

“Fer when?”

“Fer tanight!”

“Oh, well, then that’s okay! More cabbage, Nance, an’ be quick about it! We got a lot ta do yet. What time was Jase here?”

“I couldn’t say,” said the old woman, drawing a bored sigh. “I was takin’ a nap an’ I didn’t look at the clock.”

“Well, next time you looks at the clock, see, Nance!” threatened Rowley with a grim glance. “An’ Nance, ef anybody asks where we was tanight, y’ur ta say we come in early an’ et supper an’ went straight ta bed. An’ don’t ya say anuther thing, no matter how hard they press ya. See?”

“Jes’s’you say!” answered Nance sullenly and shuffled away to wash her dishes.

The night was dark, for the little thread of a moon that had appeared timidly not far from the single star had slipped away early, too young to stay up late, and the star too had pulled a cloud over its face.

But Joyce still sat there on her log watching up the road.

She did not see the side door of her home open, nor hear her stepmother calling:

“Joyce! Joyce! Come here! I want you!”

She was watching up the road.

Where was Jason?

At last she rose and slowly made her way across the pasture lot and through the Parsons’ meadow, not sure even yet that she was going to dare to go to the door and speak to Hannah Parsons. She longed so for some human beings to speak to who would understand her. And Hannah was gentle and kind. But then what would Hannah understand? She couldn’t tell her fears for her brother.

Nevertheless she made her way across the dewy grass, finally arriving at the pasture bars, and stood leaning against the post watching Hannah’s light in the kitchen window, when Rowan’s car drove in.

Joyce waited in the shadow until Rowan came out and started to close the garage doors. Then she called softly through the darkness:

“Rowan! Rowan!”

He dropped his hold on the door instantly and came over to her.

“Joyce? You here? What’s the matter?” he asked anxiously. He knew it would be no trifle that would bring shy Joyce Whitney in search of him.

“Rowan, have you seen Jason?” she asked in a whisper. “I was hoping he had been with you. He hasn’t been home all day.” Joyce’s heart was beating so fast it almost seemed to stifle her. All her pent-up anxiety of the whole day was in her voice, and her hand stole to rest at the base of her throbbing throat. She looked up eagerly into the young man’s eyes. Her own were luminous with unshed tears even in the darkness, and suddenly Rowan let down the bars and came and stood beside her, one hand resting comfortingly on her shoulder.

“No, I have not seen him,” said Rowan gravely, and his voice was gentle as one talks to a little child. Its sympathy broke down the girl’s self-control and her lips trembled.

“They say he has lost his position in the bank,” she hurried on with her explanation, “and you know what that would mean to him! He knows Father wouldn’t stand for his losing another job, and—he—maybe wouldn’t dare—come home!”

And now the tears rained down.

She put her hands up to brush them excitedly away. “I thought perhaps—you might know where I could look for him! Nobody at home will do anything. They are angry! Very angry! And Jason would do anything when he gets frantic! I’m so worried. If I could only get word to him I’d go away with him myself. I have a little money of my own that would keep us till we could find something to do. Oh, isn’t there any place you could suggest where I could look for him?”

A look almost of fear passed over Rowan’s face. “You say he’s lost his job at the bank. Are you sure?”

“I guess it’s true all right. My stepmother telephoned to Mr. Goodright. I don’t know why. She didn’t tell me what he said. She was very angry. But I know Jason. He wouldn’t stay to face a thing like that.”

“No,” said Rowan thoughtfully, “I don’t suppose he would. But I didn’t think Goodright would turn him away. I thought—”

“Oh, Jason was probably to blame,” said Jason’s sister, breaking down utterly and hiding her face in her hands for an instant. When she lifted her face, the one star had done away with the clouds and twinkled over Joyce’s tears as she looked at the young man bravely, trying to conquer the tremble in her voice. “But—he’s my brother! And I have to stand by him! Oh, don’t you know any place where I could look for him?”

“Yes!” said Rowan crisply, his lips set, his whole body tense. “I think I know one place where he would go. He told me once—never mind! I’ll find him. I’ll bring him back to you! Oh, don’t cry, dear!”

And suddenly his arms went around her, he drew her close to himself, and laid his face tenderly down on hers, kissing her wet lashes. Then his warm eager lips were on her own sweet trembling mouth, and he whispered softly with his lips against her hair:

“You are precious!”

One long moment more he held her close as she yielded her weary weakness to his strong arms, and then he let her go.

“I must go!” he said. “There wouldn’t be a minute to spare if he is gone where I think. But I’ll bring him back! You can trust me! I’ve got to go in the house for something before I start. Where will you go? Will you come in with Mother?”

“Oh no,” said Joyce, drawing back, “I must get right home! I’ll have plenty to face as it is. Nobody must know I came here.”

“Of course not!” said Rowan. “I ought to have thought of that!”

A moment more and Joyce was fleeing back through the pasture, her eyes starry with hope and Rowan’s kiss stinging sweetly upon her lips. It was the first time Rowan had kissed her. He had kissed her and said she was precious! But she mustn’t think about that now. She must only think about her brother. The kiss had been a sort of seal from Rowan that he would help her. It was almost sacred. She must not think of it any other way—not now, anyway.

She could feel his strong arms around her still, as her feet flew on across the rough pasture, going with swiftness where they would have had difficulty in walking in the day, the thrill of her spirit carrying her on as if she had wings.

And Rowan, slipping off his shoes, was stealing up the back stairs, hoping to get away without his mother’s knowing. Strange he should expect to, seeing he had hardly ever succeeded in getting away with anything like that in his life! Mother Hannah was a canny woman and had sharp ears.

He had a little money up in his room. He would need it, if things turned out as he expected.

He got the few things he was after and stuffed them in his pockets. He was on his way down again, his shoes in his hand, when he saw his mother stranding at the foot of the back stairs in a shaft of light that came from the dining room door. She was smiling up at him.

“Your dinner is ready, laddie!” she said gently, not to startle him.

“Thanks, Mother!” He smiled at her embarrassedly just as when he was a little boy about to steal away on some forbidden project. “But I’ve got to go somewhere right away. I can’t stop for dinner. It’s something important, Mother! You’ll have to trust me!”

Various emotions played over Hannah Parsons’s face in the darkness of the kitchen, but what she said was:

“All right! Here’s a sandwich to take with you! Put your shoes on and I’ll have it in a paper bag!”

She stepped to the table in full view of him as he sat on the lower step of the stairs putting on his shoes. She swept four slices of bread with butter, laid two slices of hot beef within, reached to the cupboard drawer for a paper bag, and added a thick slice of maple cake. All in one motion it seemed, and Rowan, even in his absorption and haste, took a moment to be glad of the kind of mother he had. He knew her heart was bursting with anxiety, but she would not ask him where he was going. It was her way. He was not a child anymore. He knew, too, that she was like a brave soldier sending him off with food into the unknown.

“When will you be back, laddie?” she asked in a voice that tried to be cheery.

“I can’t tell, Mother.” Rowan finished tying his shoe and stood up to take the lunch she had prepared.

“I—asked because your father said he wanted to see you. He asked that you stay up for him. Something important, he said. You know it’s his Building Association night!”

Rowan was at the door with his hand on the knob, and she was not following him but her eyes were straining him to her very soul with yearning to protect him. He read the look:

“I can’t be sure,” he explained hurriedly. “I’ll come back as soon as I can, and you and Father can trust me, Mother!”

He turned his head to look back and add:

“Tell Father it’s something he would do if he were in my place. It’s something I must do, and I—can’t explain! If I don’t get back tonight, tell him I’ll see him in the morning!”

“All right, my son!” Hannah Parsons’s voice kept steady until the end, and she stepped to the window and looked out into the darkness as the rusty old car rattled away into the night again. He hadn’t exchanged his car! Probably he was disappointed! Oh, she prayed that this thing he had to do was not any childish vengeful thing about his car, not any fancied dishonesty that must be avenged, not any unreasoning idea of crude honor.

And, Lord, don’t let him be going to Rowley’s, or anything like that! she prayed. And yet it was straight toward Rowley’s that Rowan Parsons was driving.