4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Edizioni Aurora Boreale

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

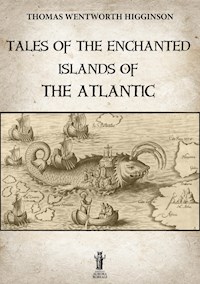

The ancient contacts between Europe and North America and the pre-columbian knowledge of the “Fourth Continent” by the ancient peoples of the Old World (Minoans, Phoenicians, Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, Celts, Vikings) are not mere hypotheses, but certainties, facts actually proved by numerous testimonies and archaeological discoveries. And these contacts and knowledges are also present in the traditions and mythology of many peoples and many contries.

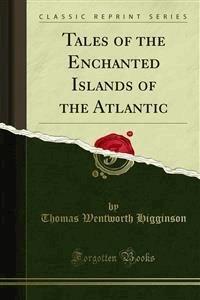

This book by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, published first time in New York in 1898, covers many of the best-known (and some lesser-known) legends and traditions about these contacts, from Atlantis to the Irish voyages of Bran, Maelduin and St. Brendan, the elusive Antillia and the Fountain of Youth which the Spanish sought, and the mysterious city of Norumbega.

The wondrous tales that gathered for more than a thousand years about the islands of the Atlantic deep are a part of the mythical period of American history. The sea has always been, by the mystery of its horizon, the fury of its storms, and the variableness of the atmosphere above it, the foreordained land of romance. In all ages and with all sea-going races there has always been something especially fascinating about an island amid the ocean. Its very existence has for all explorers an air of magic.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Symbols & Myths

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON

TALES OF THE ENCHANTED ISLANDS OF THE ATLANTIC

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Title: Tales of the Enchanted Islands of the Atlantic

Author: Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Series: Symbols & Myths

Preface by Nicola Bizzi

ISBN e-book version: 978-88-98635-71-9

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

© 2019 Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Via del Fiordaliso 14 - 59100 Prato - Italia

http://www.auroraboreale-edizioni.com

To General Sir George Wentworth Higginson, K.C.B.

Gyldernscroft, Marlow, England

THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED, IN TOKEN OF KINDRED AND OF OLD FAMILY FRIENDSHIPS, CORDIALLY PRESERVED INTO THE PRESENT GENERATION

THESE LEGENDS UNITE THE TWO SIDES OF THE

ATLANTIC AND FORM A PART OF THE COMMON

HERITAGE OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING RACE

INTRODUCTION OF THE PUBLISHER

The ancient contacts between Europe and North America and the pre-columbian knowledge of the “Fourth Continent” by the ancient peoples of the Old World (Minoans, Phoenicians, Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, Celts, Vikings) are not mere hypotheses, but certainties, facts actually proved by numerous testimonies and archaeological discoveries. And these contacts and knowledges are also present in the traditions and mythology of many peoples and many contries.

This book by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, published first time in New York in 1898, covers many of the best-known (and some lesser-known) legends and traditions about these contacts, from Atlantis to the Irish voyages of Bran, Maelduin and St. Brendan, the elusive Antillia and the Fountain of Youth which the Spanish sought, and the mysterious city of Norumbega.

The wondrous tales that gathered for more than a thousand years about the islands of the Atlantic deep are a part of the mythical period of American history. The sea has always been, by the mystery of its horizon, the fury of its storms, and the variableness of the atmosphere above it, the foreordained land of romance. In all ages and with all sea-going races there has always been something especially fascinating about an island amid the ocean. Its very existence has for all explorers an air of magic.

The order of the tales in the present work follows roughly the order of development, giving first the legends which kept near the European shore, and then those which, like St. Brandan’s or Antillia, were assigned to the open sea or, like Norumbega or the Isle of Demons, to the very coast of America. Every tale in this book bears reference to some actual legend, followed more or less closely, and the authorities for each will be found carefully given in the appendix for such readers as may care to follow the subject farther.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, and soldier. He was active in the American Abolitionism movement during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with disunion and militant abolitionism. He was a member of the Secret Six who supported John Brown. During the Civil War, he served as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first federally authorized black regiment, from 1862 to 1864. Following the war, Higginson devoted much of the rest of his life to fighting for the rights of freed slaves, women and other disfranchised peoples.

Higginson was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts on December 22, 1823. He was a descendant of Francis Higginson, a Puritan minister and emigrant to the colony of Massachusetts Bay. His father, Stephen Higginson (born Salem, Massachusetts, November 20, 1770; died Cambridge, Massachusetts, February 20, 1834), was a merchant and philanthropist in Boston and steward of Harvard University from 1818 until 1834. His grandfather, also named Stephen Higginson, was a member of the Continental Congress. He was a distant cousin of Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a great grandson of his grandfather. A third great grand father was New Hampshire Lieutenant-Governor John Wentworth.

Higginson attended Harvard College at age thirteen and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa at sixteen. He graduated in 1841, and was a schoolmaster for two years and, in 1842, became engaged to Mary Elizabeth Channing. He then studied Theology at the Harvard Divinity School. At the end of his first year of divinity training, he withdrew from the school to turn his attention to the abolitionist cause. He spent the subsequent year studying and, following the lead of Transcendentalist Unitarian minister Theodore Parker, fighting against the expected war with Mexico. Believing that war was only an excuse to expand slavery and the slave power, Higginson wrote anti-war poems and went door-to-door to get signatures for anti-war petitions. With the split of the anti-slavery movement in the 1840s, Higginson subscribed to the Disunion Abolitionists, who believed that as long as slave states remained a part of the union, Constitutional support for slavery could never be amended.

Higginson married Mary Channing in 1847 after graduating from divinity school. Mary was the daughter of Dr. Walter Channing, a pioneer in the field of Obstetrics and Gynecology who taught at Harvard University, the niece of Unitarian minister, William Ellery Channing, and the sister of Henry David Thoreau’s friend, Ellery Channing. Higginson and Mary Channing had no children but raised Margaret Fuller Channing, the eldest daughter of Ellen Fuller and Ellery Channing. Ellen was the sister of the Transcendentalist and feminist author, Margaret Fuller. Two years after his wife Mary’s death in 1877, Higginson married Mary Potter Thacher, with whom he had two daughters, one of whom survived into adulthood.

A year after leaving school, a growing passion for abolitionism led Higginson to recommence his divinity studies and he graduated in 1847. Higginson was called as pastor at the First Religious Society of Newburyport, Massachusetts, a Unitarian church known for its liberal Christianity. He supported the Essex County Antislavery Society and criticized the poor treatment of workers at Newburyport cotton factories. Additionally, the young minister invited Theodore Parker and fugitive slave William Wells Brown to speak at the church, and in sermons he condemned northern apathy towards slavery. In his role as board member of the New-buryport Lyceum and against the wishes of the majority of the board, Higginson brought Ralph Waldo Emerson to speak. Higginson proved too radical for the congregation and was forced to resign in 1848.

The Compromise of 1850 brought new challenges and new ambitions for the unemployed minister. He ran as the Free Soil party candidate in the Massachusetts Third Congressional District in 1850, but lost. Higginson called upon citizens to up-hold God’s law and disobey the Fugitive Slave Act. He joined the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization whose purpose was to protect fugitive slaves from pursuit and capture.His joining of the group was inspired by the arrest and trial of the free black Frederick Jenkins, known as Shadrach. Abolitionists helped him escape to Canada. He participated with Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker in the attempt at freeing Thomas Sims, a Georgia slave who had escaped to Boston.

In 1854, when the escaped Anthony Burns was threatened with ex-tradition under the Fugitive Slave Act, Higginson led a small gro-up who stormed the federal courthouse in Boston with battering rams, axes, cleavers, and revolvers. They could not prevent Burns from being taken back to the South. Higginson received a saber slash on his chin; he wore the scar proudly for the rest of his life.

In 1852, Higginson became pastor of the Free Church in Worcester. During his tenure, Higginson not only supported abolition, but also temperance, labor rights, and rights of women.

Returning from a voyage to Europe for the health of his wife, who had an unknown illness, Higginson organized a group of men on behalf of the New England Emigration Aid Company to use peaceful means as tensions rose after the passage of the Kan-sas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The act divided the region into the Kansas and Nebraska territories, whose residents would separately vote on whether to allow slavery within each jurisdiction’s borders. Both abolitionist and pro-slavery supporters began to migrate to the territories. After his return, Higginson worked to keep activism aroused in New England by speechmaking, fundraising, and helping to organize the Massachusetts Kansas Aid Committee. He returned to the Kansas territory as an agent of the National Kansas Aid Committee, working to rebuild morale and distribute supplies to settlers. Higginson became convinced that abolition could not be attained by peaceful methods.

As sectional conflict escalated, he continued to support disunion abolitionism, organizing the Worcester Disunion Convention in 1857. The convention asserted abolition as its primary goal, even if it would lead the country to war. Higginson was a fervent supporter of John Brown and is remembered as one of the “Secret Six” abolitionists who helped Brown raise money and procure supplies for his intended slave insurrection at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. When Brown was captured, Higginson tried to raise money for a trial defense and made plans to help the leader escape from prison, though he was ultimately unsuccessful. Other members of the Secret Six fled to Canada or elsewhere after Brown’s capture, but Higginson never fled, despite his involvement being common knowledge. Higginson was never arrested or called to testify.

Higginson was one of leading male advocates of woman’s rights during the decade before the Civil War. In 1853, he addressed the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in support of a petition asking that women be allowed to vote on ratification of the new constitution. Published as Woman and Her Wishes, the address was used many years as a woman’s rights tract, as was an 1859 article he wrote for the Atlantic Monthly, Ought Women to Learn the Alphabet?. A close friend and supporter of woman’s rights leader Lucy Stone, he performed the marriage ceremony of Stone and Henry B. Blackwell in 1855 and, by sending their protest of unjust marriage laws to the press, was responsible for their “Marriage Protest” becoming a famous document. Together with Stone, he compiled and published The Woman’s Rights Almanac for 1858, which provided data such as income disparity between the sexes as well as a summary of gains made by the national movement during its first seven years. He also compiled and published, in 1858, Consistent Democracy: The Elective Franchise for Women. Twenty-five Testimonies of Prominent Men, brief excerpts favoring woman suffrage from the speeches or writing of such men as Wendell Phillips, Henry Ward Beecher, Rev. Wm. H. Channing, Horace Greeley, Gerrit Smith, and various governors, legislators, and legislative reports. A member of the National Woman’s Rights Central Committee since 1853 or 1854, he was one of nine activists retained in that post when that large body of state representatives was reduced in 1858.

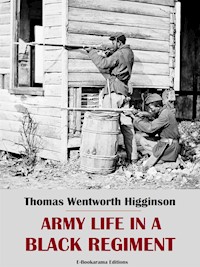

During the early part of the Civil War, Higginson was a captain in the 51st Massachusetts Infantry from November 1862 to October 1864, when he was retired because of a wound received in the preceding August. He was colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first authorized regiment recruited from freedmen for Union military service. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton required that black regiments be commanded by white officers. Higginson described his Civil War experiences in Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870), which has been published online by Project Gutenberg (gutenberg.org). He contributed to the preservation of Negro spirituals by copying dialect verses and music he heard sung around the regiment’s campfires. In his book, Drawn by the Sword, historian James M. McPherson argued that Higginson’s service as a Union soldier showed in part that he did not share the “powerful racial prejudices” of others during the time period.

After the Civil War, Higginson was an organizer of the New England Woman Suffrage Association in 1868, and of the American Woman Suffrage Association the following year. He was one of the original editors of the suffrage newspaper The Woman’s Journal, founded in 1870, and contributed a front-page column to it for fourteen years. As a two-year member of the Massachusetts legislature, 1880–82, he was a valuable link bet-ween suffragists and the legislature.

Higginson became active in the Free Religious Association (FRA) and delivered the speech The Sympathy of Religions in 1870, which was later published and circulated. The address argued that all religions shared essential truths and a common exhortation toward benevolence, and that, indeed, division among them was ultimately artificial: «Every step in the progress of each brings it nearer to all the rest. For us, the door out of superstition and sin may be called Christianity; that is an historical name only, the accident of a birthplace. But other nations find other outlets; they must pass through their own doors». He pushed the FRA to tolerate even those who did not accept the liberal principles the Association espoused, asking «Are we as large as our theory? ...Are we as ready to tolerate the Evangelical man as the Mohammedan?». Although his own relationship to evangelical Protestants remained strained, he saw the exclusion of any religious mindset as fundamentally dangerous to the organization.

Higginson spoke at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1893 and praised the great strides that had been made in the mutual understanding of the world’s great religions, describing the Parliament as the culmination of the FRA’s greatest ambitions.

After the Civil War, he devoted most of his time to literature. His writings show a deep love of nature, art and humanity. In his Common Sense About Women (1881) and his Women and Men (1888), he advocated equality of opportunity and equality of rights for the two sexes.

In 1874 was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society and in 1891 became one of the founders of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom (SAFRF). He edited its public appeal “To the Friends of Russian Freedom”. In 1905, he joined with Jack London and Upton Sinclair to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. He also was an Advisory Editor for the second attempt at The Massachusetts Magazine. Later, in 1907 Higginson was the vice-president of the SAFRF.

Higginson died May 9, 1911. Although his death record states that he was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he is actually buried in Cambridge Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the intersection of Riverview, Lawn, and Prospect paths.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Surviving fragment of the Piri Reis Worls Map, compiled in 1513 by the Turkish admiral and cartographer Ahmed Muhiddin Piri, better known as Piri Reis, showing the Central and South American coast and part of the Antarctica (Istanbul, Library of the Topkapi Palace).

PREFACE

Hawthorne in his Wonder Book has described the beautiful Greek myths and traditions, but no one has yet made similar use of the wondrous tales that gathered for more than a thousand years about the islands of the Atlantic deep. Although they are a part of the mythical period of American history, these hazy legends were altogether disdained by the earlier historians; indeed, George Bancroft made it a matter of actual pride that the beginning of the American annals was bare and literal. But in truth no national history has been less prosaic as to its earlier traditions, because every visitor had to cross the sea to reach it, and the sea has always been, by the mystery of its horizon, the fury of its storms, and the variableness of the atmosphere above it, the foreordained land of romance.

In all ages and with all sea-going races there has always been something especially fascinating about an island amid the ocean. Its very existence has for all explorers an air of magic. An island offers to us heights rising from depths; it exhibits that which is most fixed beside that which is most changeable, the fertile beside the barren, and safety after danger. The ocean forever tends to encroach on the island, the island upon the ocean. They exist side by side, friends yet enemies. The island signifies safety in calm, and yet danger in storm; in a tempest the sailor rejoices that he is not near it; even if previously bound for it, he puts about and steers for the open sea. Often if he seeks it he cannot reach it. The present writer spent a winter on the island of Fayal, and saw in a storm a full-rigged ship drift through the harbor disabled, having lost her anchors; and it was a week before she again made the port.

There are groups of islands scattered over the tropical ocean, especially, to which might well be given Herman Melville’s name, “Las Encantadas”, the Enchanted Islands. These islands, usually volcanic, have no vegetation but cactuses or wiry bushes with strange names; no inhabitants but insects and reptiles – lizards, spiders, snakes – with vast tortoises which seem of immemorial age, and are coated with seaweed and the slime of the ocean. If there are any birds, it is the strange and heavy penguin, the passing albatross, or the Mother Cary’s chicken, which has been called the humming bird of ocean, and here finds a place for its young. By night these birds come for their repose; at earliest dawn they take wing and hover over the sea, leaving the isle deserted. The only busy or beautiful life which always surrounds it is that of a myriad species of fish, of all forms and shapes, and often more gorgeous than any butterflies in gold and scarlet and yellow.

Once set foot on such an island and you begin at once to understand the legends of enchantment which ages have collected around such spots. Climb to its heights, you seem at the mas-thead of some lonely vessel, kept forever at sea. You feel as if no one but yourself had ever landed there; and yet, perhaps, even there, looking straight downward, you see below you in some crevice of the rock a mast or spar of some wrecked vessel, encrusted with all manner of shells and uncouth vegetable growth. No matter how distant the island or how peacefully it seems to lie upon the water, there may be perplexing currents that ever foam and swirl about it – currents which are, at all tides and in the calmest weather, as dangerous as any tempest, and which make compass untrustworthy and helm powerless. It is to be remembered also that an island not only appears and disappears upon the horizon in brighter or darker skies, but it varies its height and shape, doubles itself in mirage, or looks as if broken asunder, divided into two or three. Indeed the buccaneer, Cowley, writing of one such island which he had visited, says: «My fancy led me to call it Cowley’s Enchanted Isle, for we having had a sight of it upon several points of the compass, it appeared always in so many different forms; sometimes like a ruined fortification; upon another point like a great city».

If much of this is true even now, it was far truer before the days of Columbus, when men were constantly looking westward across the Atlantic, and wondering what was beyond. In those days, when no one knew with certainty whether the ocean they observed was a sea or a vast lake, it was often called “The Sea of Darkness”. A friend of the Latin poet, Ovid, describing the first approach to this sea, says that as you sail out upon it the day itself vanishes, and the world soon ends in perpetual darkness:

«Quo ferimur? Ruit ipsa Dies, orbemque relictumUltima perpetuis claudit natura tenebris».

Nevertheless, it was the vague belief of many nations that the abodes of the blest lay somewhere beyond it in the “other world”, a region half earthly, half heavenly, whence the spirits of the departed could not cross the water to return; and so they were constantly imagining excursions made by favored mortals to enchanted islands. To add to the confusion, actual islands in the Atlantic were sometimes discovered and actually lost again, as, for instance, the Canaries, which were reached and called the Fortunate Isles a little before the Christian era, and were then lost to sight for thirteen centuries ere being visited again.

The glamour of enchantment was naturally first attached by Europeans to islands within sight of their own shores – Irish, Welsh, Breton, or Spanish – and then, as these islands became better known, men’s imaginations carried the mystery further out over the unknown western sea. The line of legend gradually extended itself till it formed an imaginary chart for Columbus; the aged astronomer, Toscanelli, for instance, suggesting to him the advantage of making the supposed island of Antillia a half-way station; just as it was proposed, long centuries after, to find a station for the ocean telegraph in the equally imaginary island of Jacquet, which has only lately disappeared from the charts. With every step in knowledge the line of fancied stopping-places rearranged itself, the fictitious names flitting from place to place on the maps, and sometimes duplicating themselves. Where the tradition itself has vanished we find that the names with which it associated itself are still assigned, as in case of Brazil and the Antilles, to wholly different localities.

The order of the tales in the present work follows roughly the order of development, giving first the legends which kept near the European shore, and then those which, like St. Brandan’s or Antillia, were assigned to the open sea or, like Norumbega or the Isle of Demons, to the very coast of America. Every tale in this book bears reference to some actual legend, followed more or less closely, and the authorities for each will be found carefully given in the appendix for such readers as may care to follow the subject farther. It must be remembered that some of these imaginary islands actually remained on the charts of the British admiralty until within a century. If even the exact science of geographers retained them thus long, surely romance should embalm them forever.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Cambridge, Massachussets, 1898.

Bust of Plato, Roman imperial age

(Rome, Vatican Museum)

CHAPTER I

THE STORY OF ATLANTIS

The Greek sage Socrates, when he was but a boy minding his father’s goats, used to lie on the grass under the myrtle trees; and, while the goats grazed around him, he loved to read over and over the story which Solon, the law-giver and poet, wrote down for the great-grandfather of Socrates, and which Solon had always meant to make into a poem, though he died without doing it. But this was briefly what he wrote in prose:

«I, Solon, was never in my life so surprised as when I went to Egypt for instruction in my youth, and there, in the temple of Sais, saw an aged priest who told me of the island of Atlantis, which was sunk in the sea thousands of years ago. He said that in the division of the earth the gods agreed that the god Poseidon, or Neptune, should have, as his share, this great island which then lay in the ocean west of the Mediterranean Sea, and was larger than all Asia. There was a mortal maiden there whom Poseidon wished to marry, and to secure her he surrounded the valley where she dwelt with three rings of sea and two of land so that no one could enter; and he made underground springs, with water hot or cold, and supplied all things needful to the life of man. Here he lived with her for many years, and they had ten sons; and these sons divided the island among them and had many children, who dwelt there for more than a thousand years. They had mines of gold and silver, and pastures for elephants, and many fragrant plants. They erected palaces and dug canals; and they built their temples of white, red, and black stone, and covered them with gold and silver. In these were statues of gold, especially one of the god Poseidon driving six winged horses. He was so large as to touch the roof with his head, and had a hundred water-nymphs around him, riding on dolphins. The islanders had also baths and gardens and sea-walls, and they had twelve hundred ships and ten thousand chariots. All this was in the royal city alone, and the people were friendly and good and well-affectioned towards all. But as time went on they grew less so, and they did not obey the laws, so that they offended heaven. In a single day and night the island disappeared and sank beneath the sea; and this is why the sea in that region grew so impassable and impenetrable, because there is a quantity of shallow mud in the way, and this was caused by the sinking of a single vast island».

«This is the tale – said Solon – which the old Egyptian priest told to me». And Solon’s tale was read by Socrates, the boy, as he lay in the grass; and he told it to his friends after he grew up, as is written in his dialogues recorded by his disciple, Plato. And though this great island of Atlantis has never been seen again, yet a great many smaller islands have been found in the Atlantic Ocean, and they have sometimes been lost to sight and found again.

There is, also, in this ocean a vast tract of floating seaweed, called by sailors the Sargasso Sea, covering a region as large as France, and this has been thought by many to mark the place of a sunken island. There are also many islands, such as the Azores, which have been supposed at different times to be fragments of Atlantis; and besides all this, the remains of the vanished island have been looked for in all parts of the world. Some writers have thought it was in Sweden, others in Spitzbergen, others in Africa, in Palestine, in America. Since the depth of the Atlantic has been more thoroughly sounded, a few writers have maintained that the inequalities of its floor show some traces of the submerged Atlantis, but the general opinion of men of science is quite the other way. The visible Atlantic islands are all, or almost all, they say, of volcanic origin; and though there are ridges in the bottom of the ocean, they do not connect the continents.

At any rate, this was the original story of Atlantis, and the legends which follow in these pages have doubtless all grown, more or less, out of this first tale which Socrates told.

Map of Atlantis from Mundus Subterraneus by Athanasius Kircher,

Amsterdam 1665

Fantasy reconstruction of a hypothetical Atlantean landscape

CAPTER II

TALIESSIN OF THE RADIANT BROW

In times past there were enchanted islands in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Wales, and even now the fishermen sometimes think they see them. On one of these there lived a man named Tegid Voel and his wife called Cardiwen. They had a son, the ugliest boy in the world, and Cardiwen formed a plan to make him more attractive by teaching him all possible wisdom. She was a great magician and resolved to boil a large caldron full of knowledge for her son, so that he might know all things and be able to predict all that was to happen. Then she thought people would value him in spite of his ugliness. But she knew that the caldron must burn a year and a day without ceasing, until three blessed drops of the water of knowledge were obtained from it; and those three drops would give all the wisdom she wanted.

So she put a boy named Gwion to stir the caldron and a blind man named Morda to feed the fire; and made them promise ne-ver to let it cease boiling for a year and a day. She herself kept gathering magic herbs and putting them into it. One day when the year was nearly over, it chanced that three drops of the liquor flew out of the caldron and fell on the finger of Gwion. They were fiery hot, and he put his finger to his mouth, and the instant he tasted them he knew that they were the enchanted drops for which so much trouble had been taken. By their magic he at once foresaw all that was to come, and especially that Cardiwen the enchantress would never forgive him.

Then Gwion fled. The caldron burst in two, and all the liquor flowed forth, poisoning some horses which drank it. These horses belonged to a king named Gwyddno. Cardiwen came in and saw all the toil of the whole year lost. Seizing a stick of wood, she struck the blind man Morda fiercely on the head, but he said, «I am innocent. It was not I who did it». «True, – said Cardiwen – it was the boy Gwion who robbed me»; and she rushed to pursue him. He saw her and fled, changing into a hare; but she became a greyhound and followed him. Running to the water, he became a fish; but she became another and chased him below the waves. He turned himself into a bird, when she became a hawk and gave him no rest in the sky. Just as she swooped on him, he espied a pile of winnowed wheat on the floor of a barn, and dropping upon it, he became one of the wheat-grains. Changing herself into a high-crested black hen, Cardiwen scratched him up and swallowed him, when he changed at last into a boy again and was so beautiful that she could not kill him outright, but wrapped him in a leathern bag and cast him into the sea, committing him to the mercy of God. This was on the twenty-ninth of April.