2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Interactive Media

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

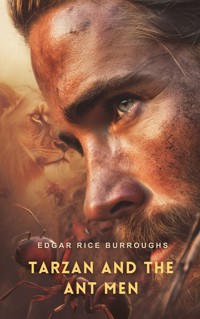

Tarzan and the Ant Men is a novel written by Edgar Rice Burroughs. In the book, Tarzan travels to Africa where he meets a race of ant-like creatures called the Ant Men. The Ant Men are a peaceful people who live in a society that is based on equality and cooperation. Tarzan eventually becomes their leader and helps them protect their society from danger.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Tarzan and the Ant Men

New Edition

New Edition

Published by Fantastica

This Edition

First published in 2022

Copyright © 2022 Fantastica

All Rights Reserved.

ISBN: 9781787363830

Contents

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER I

In the filth of a dark hut, in the village of Obebe the cannibal, upon the banks of the Ugogo, Esteban Miranda squatted upon his haunches and gnawed upon the remnants of a half-cooked fish. About his neck was an iron slave collar from which a few feet of rusty chain ran to a stout post set deep in the ground near the low entranceway that let upon the village street not far from the hut of Obebe himself.

For a year Esteban Miranda had been chained thus, like a dog, and like a dog he sometimes crawled through the low doorway of his kennel and basked in the sun outside. Two diversions had he; and only two. One was the persistent idea that he was Tarzan of the Apes, whom he had impersonated for so long and with such growing success that, like the good actor he was, he had come not only to act the part, but to live it—to be it. He was, as far as he was concerned, Tarzan of the Apes—there was no other—and he was Tarzan of the Apes to Obebe, too; but the village witch doctor still insisted that he was the river devil and as such, one to propitiate rather than to anger.

It had been this difference of opinion between the chief and the witch doctor that had kept Esteban Miranda from the flesh pots of the village, for Obebe had wanted to eat him, thinking him his old enemy the ape-man; but the witch doctor had aroused the superstitious fears of the villagers by half convincing them that their prisoner was the river devil masquerading as Tarzan, and, as such, dire disaster would descend upon the village were he harmed. The result of this difference between Obebe and the witch doctor had been to preserve the life of the Spaniard until the truth of one claim or the other was proved—if Esteban died a natural death he was Tarzan, the mortal, and Obebe the chief was vindicated; if he lived on forever, or mysteriously disappeared, the claim of the witch doctor would be accepted as gospel.

After he had learned their language and thus come to a realization of the accident of fate that had guided his destiny by so narrow a margin from the cooking pots of the cannibals he was less eager to proclaim himself Tarzan of the Apes. Instead he let drop mysterious suggestions that he was, indeed, none other than the river devil. The witch doctor was delighted, and everyone was fooled except Obebe, who was old and wise and did not believe in river devils, and the witch doctor who was old and wise and did not believe in them either, but realized that they were excellent things for his parishioners to believe in.

Esteban Miranda’s other diversion, aside from secretly believing himself Tarzan, consisted in gloating over the bag of diamonds that Kraski the Russian had stolen from the ape-man, and that had fallen into the Spaniard’s hands after he had murdered Kraski—the same bag of diamonds that the old man had handed to Tarzan in the vaults beneath The Tower of Diamonds, in the Valley of The Palace of Diamonds, when he had rescued the Gomangani of the valley from the tyrannical oppression of the Bolgani.

For hours at a time Esteban Miranda sat in the dim light of his dirty kennel counting and fondling the brilliant stones. A thousand times had he weighed each one in an appraising palm, computing its value and translating it into such pleasures of the flesh as great wealth might buy for him in the capitals of the world. Mired in his own filth, feeding upon rotted scraps tossed to him by unclean hands, he yet possessed the wealth of a Croesus, and it was as Croesus he lived in his imaginings, his dismal hut changed into the pomp and circumstance of a palace by the scintillant gleams of the precious stones. At the sound of each approaching footstep he would hastily hide his fabulous fortune in the wretched loin cloth that was his only garment, and once again become a prisoner in a cannibal hut.

And now, after a year of solitary confinement, came a third diversion, in the form of Uhha, the daughter of Khamis the witch doctor. Uhha was fourteen, comely and curious. For a year now she had watched the mysterious prisoner from a distance until, at last, familiarity had overcome her fears and one day she approached him as he lay in the sun outside his hut. Esteban, who had been watching her half-timorous advance, smiled encouragingly. He had not a friend among the villagers. If he could make but one his lot would be much the easier and freedom a step nearer. At last Uhha came to a halt a few steps from him. She was a child, ignorant and a savage; but she was a woman-child and Esteban Miranda knew women.

“I have been in the village of the chief Obebe for a year,” he said haltingly, in the laboriously acquired language of his captors, “but never before did I guess that its walls held one so beautiful as you. What is your name?”

Uhha was pleased. She smiled broadly. “I am Uhha,” she told him. “My father is Khamis the witch doctor.”

It was Esteban who was pleased now. Fate, after rebuffing him for long, was at last kind. She had sent to him one who, with cultivation, might prove a flower of hope indeed.

“Why have you never come to see me before?” asked Esteban.

“I was afraid,” replied Uhha simply.

“Why?”

“I was afraid—” she hesitated.

“Afraid that I was the river devil and would harm you?” demanded the Spaniard, smiling.

“Yes,” she said.

“Listen!” whispered Esteban; “but tell no one. I am the river devil, but I shall not harm you.”

“If you are the river devil why then do you remain chained to a stake?” inquired Uhha. “Why do you not change yourself to something else and return to the river?”

“You wonder about that, do you?” asked Miranda, sparring for time that he might concoct a plausible answer.

“It is not only Uhha who wonders,” said the girl. “Many others have asked the same question of late. Obebe asked it first and there was none to explain. Obebe says that you are Tarzan, the enemy of Obebe and his people; but my father Khamis says that you are the river devil, and that if you wanted to get away you would change yourself into a snake and crawl through the iron collar that is about your neck. And the people wonder why you do not, and many of them are commencing to believe that you are not the river devil at all.”

“Come closer, beautiful Uhha,” whispered Miranda, “that no other ears than yours may hear what I am about to tell you.”

The girl came a little closer and leaned toward him where he squatted upon the ground.

“I am indeed the river devil,” said Esteban, “and I come and go as I wish. At night, when the village sleeps, I am wandering through the waters of the Ugogo, but always I come back again. I am waiting, Uhha, to try the people of the village of Obebe that I may know which are my friends and which my enemies. Already have I learned that Obebe is no friend of mine, and I am not sure of Khamis. Had Khamis been a good friend he would have brought me fine food and beer to drink. I could go when I pleased, but I wait to see if there be one in the village of Obebe who will set me free. Thus may I learn which is my best friend. Should there be such a one, Uhha, fortune would smile upon him always, his every wish would be granted and he would live to a great age, for he would have nothing to fear from the river devil, who would help him in all his undertakings. But listen, Uhha, tell no one what I have told you! I shall wait a little longer, and then if there be no such friend in the village of Obebe I shall return to my father and mother, the Ugogo, and destroy the people of Obebe. Not one shall remain alive.”

The girl drew away, terrified. It was evident that she was much impressed.

“Do not be afraid,” he reassured her. “I shall not harm you.”

“But if you destroy all the people?” she demanded.

“Then, of course,” he said, “I cannot help you; but let us hope that someone comes and sets me free so that I shall know that I have at least one good friend here. Now run along, Uhha, and remember that you must tell no one what I have told you.”

She moved off a short distance and then returned.

“When will you destroy the village?” she asked.

“In a few days,” he said.

Uhha, trembling with terror, ran quickly away in the direction of the hut of her father, Khamis, the witch doctor. Esteban Miranda smiled a satisfied smile and crawled back into his hole to play with his diamonds.

Khamis the witch doctor was not in his hut when Uhha his daughter, faint from fright, crawled into the dim interior. Nor were his wives. With their children, the latter were in the fields beyond the palisade, where Uhha should have been. And so it was that the girl had time for thought before she saw any of them again, with the result that she recalled distinctly, what she had almost forgotten in the first frenzy of fear, that the river devil had impressed upon her that she must reveal to no one the thing that he had told her.

And she had been upon the point of telling her father all! What dire calamity then would have befallen her? She trembled at the very suggestion of a fate so awful that she could not even imagine it. How close a call she had had! But what was she to do?

She lay huddled upon a mat of woven grasses, racking her poor, savage little brain for a solution of the immense problem that confronted her—the first problem that had ever entered her young life other than the constantly recurring one of how most easily to evade her share of the drudgery of the fields. Presently she sat suddenly erect, galvanized into statuesque rigidity by a thought engendered by the recollection of one of the river devil’s remarks. Why had it not occurred to her before? Very plainly he had said, and he had repeated it, that if he were released he would know that he had at least one friend in the village of Obebe, and that whoever released him would live to a great age and have every thing he wished for; but after a few minutes of thought Uhha drooped again. How was she, a little girl, to compass the liberation of the river devil alone?

“How, baba,” she asked her father, when he had returned to the hut, later in the day, “does the river devil destroy those who harm him?”

“As the fish in the river, so are the ways of the river devil—without number,” replied Khamis. “He might send the fish from the river and the game from the jungle and cause our crops to die. Then we should starve. He might bring the fire out of the sky at night and strike dead all the people of Obebe.”

“And you think he may do these things to us, baba?”

“He will not harm Khamis, who saved him from the death that Obebe would have inflicted,” replied the witch doctor.

Uhha recalled that the river devil had complained that Khamis had not brought him good food nor beer, but she said nothing about that, although she realized that her father was far from being so high in the good graces of the river devil as he seemed to think he was. Instead, she took another tack.

“How can he escape,” she asked, “while the collar is about his neck—who will remove it for him?”

“No one can remove it but Obebe, who carries in his pouch the bit of brass that makes the collar open,” replied Khamis; “but the river devil needs no help, for when the time comes that he wishes to be free he has but to become a snake and crawl forth from the iron band about his neck. Where are you going, Uhha?”

“I am going to visit the daughter of Obebe,” she called back over her shoulder.

The chief’s daughter was grinding maize, as Uhha should have been doing. She looked up and smiled as the daughter of the witch doctor approached.

“Make no noise, Uhha,” she cautioned, “for Obebe, my father, sleeps within.” She nodded toward the hut. The visitor sat down and the two girls chatted in low tones. They spoke of their ornaments, their coiffures, of the young men of the village, and often, when they spoke of these, they giggled. Their conversation was not unlike that which might pass between two young girls of any race or clime. As they talked, Uhha’s eyes often wandered toward the entrance to Obebe’s hut and many times her brows were contracted in much deeper thought than their idle passages warranted.

“Where,” she demanded suddenly, “is the armlet of copper wire that your father’s brother gave you at the beginning of the last moon?”

Obebe’s daughter shrugged. “He took it back from me,” she replied, “and gave it to the sister of his youngest wife.”

Uhha appeared crest-fallen. Could it be that she had coveted the copper bracelet? Her eyes closely scrutinized the person of her friend. Her brows almost met, so deeply was she thinking. Suddenly her face brightened.

“The necklace of many beads that your father took from the body of the warrior captured for the last feast!” she exclaimed. “You have not lost it?”

“No,” replied her friend. “It is in the house of my father. When I grind maize it gets in my way and so I laid it aside.”

“May I see it?” asked Uhha. “I will fetch it.”

“No, you will awaken Obebe and he will be very angry,” said the chief’s daughter.

“I will not awaken him,” replied Uhha, and started to crawl toward the hut’s entrance.

Her friend tried to dissuade her. “I will fetch it as soon as baba has awakened,” she told Uhha, but Uhha paid no attention to her and presently was crawling cautiously into the interior of the hut. Once within she waited silently until her eyes became accustomed to the dim light. Against the opposite wall of the hut Obebe lay sprawled upon a sleeping mat. He snored lustily. Uhha crept toward him. Her stealth was the stealth of Sheeta the leopard. Her heart was beating like the tom-tom when the dance is at its height. She feared that its noise and her rapid breathing would awaken the old chief, of whom she was as terrified as of the river devil; but Obebe snored on.

Uhha came close to him. Her eyes were accustomed now to the half-light of the hut’s interior. At Obebe’s side and half beneath his body she saw the chief’s pouch. Cautiously she reached forth a trembling hand and laid hold upon it. She tried to draw it from beneath Obebe’s weight. The sleeper stirred uneasily and Uhha drew back, terrified. Obebe changed his position and Uhha thought that he had awakened. Had she not been frozen with horror she would have rushed into headlong flight, but fortunately for her she could not move, and presently she heard Obebe resume his interrupted snoring; but her nerve was gone and she thought now only of escaping from the hut without being detected. She cast a last frightened glance at the chief to reassure herself that he still slept. Her eyes fell upon the pouch. Obebe had turned away from it and it now lay within her reach, free from the weight of his body.

She reached for it only to withdraw her hand suddenly. She turned away. Her heart was in her mouth. She swayed dizzily and then she thought of the river devil and of the possibilities for horrid death that lay within his power. Once more she reached for the pouch and this time she picked it up. Hurriedly opening it she examined the contents. The brass key was there. She recognized it because it was the only thing the purpose of which she was not familiar with. The collar, chain and key had been taken from an Arab slave raider that Obebe had killed and eaten and as some of the old men of Obebe’s village had worn similar bonds in the past, there was no difficulty in adapting it to its intended purpose when occasion demanded.

Uhha hastily closed the pouch and replaced it at Obebe’s side. Then, clutching the key in a clammy palm, she crawled hurriedly toward the doorway.

That night, after the cooking fires had died to embers and been covered with earth and the people of Obebe had withdrawn into their huts, Esteban Miranda heard a stealthy movement at the entrance to his kennel. He listened intently. Someone was creeping into the interior—someone or something.

“Who is it?” demanded the Spaniard in a voice that he tried hard to keep from trembling.

“Hush!” responded the intruder in soft tones. “It is I, Uhha, the daughter of Khamis the witch doctor. I have come to set you free that you may know that you have a good friend in the village of Obebe and will, therefore, not destroy us.”

Miranda smiled. His suggestion had borne fruit more quickly than he had dared to hope, and evidently the girl had obeyed his injunction to keep silent. In that matter he had reasoned wrongly, but of what moment that, since his sole aim in life—freedom—was to be accomplished. He had cautioned the girl to silence believing this the surest way to disseminate the word he had wished spread through the village, where, he was positive, it would have come to the ears of some one of the superstitious savages with the means to free him now that the incentive was furnished.

“And how are you going to free me?” demanded Miranda.

“See!” exclaimed Uhha. “I have brought the key to the collar about your neck.”

“Good,” cried the Spaniard. “Where is it?”

Uhha crawled closer to the man and handed him the key. Then she would have fled.

“Wait!” demanded the prisoner. “When I am free you must lead me forth into the jungle. Whoever sets me free must do this if he would win the favor of the river god.”

Uhha was afraid, but she did not dare refuse. Miranda fumbled with the ancient lock for several minutes before it at last gave to the worn key the girl had brought. Then he snapped the padlock again and carrying the key with him crawled toward the entrance.

“Get me weapons,” he whispered to the girl and Uhha departed through the shadows of the village street. Miranda knew that she was terrified but was confident that this very terror would prove the means of bringing her back to him with the weapons. Nor was he wrong, for scarce five minutes had elapsed before Uhha had returned with a quiver of arrows, a bow and a stout knife.

“Now lead me to the gate,” commanded Esteban.

Keeping out of the main street and as much in rear of the huts as possible Uhha led the fugitive toward the village gates. It surprised her a little that he, a river devil, should not know how to unlock and open them, for she had thought that river devils were all-wise; but she did as he bid and showed him how the great bar could be withdrawn, and helped him push the gates open enough to permit him to pass through. Beyond was the clearing that led to the river, on either hand rose the giants of the jungle. It was very dark out there and Esteban Miranda suddenly discovered that his new-found liberty had its drawbacks. To go forth alone at night into the dark, mysterious jungle filled him with a nameless dread.

Uhha drew back from the gates. She had done her part and saved the village from destruction. Now she wished to close the gates again and hasten back to the hut of her father, there to lie trembling in nervous excitement and terror against the morning that would reveal to the village the escape of the river devil.

Esteban reached forth and took her by the arm. “Come,” he said, “and receive your reward.”

Uhha shrank away from him. “Let me go!” she cried. “I am afraid.”

But Esteban was afraid, too, and he had decided that the company of this little negro girl would be better than no company at all in the depths of the lonely jungle. Possibly when daylight came he would let her go back to her people, but tonight he shuddered at the thought of entering the jungle without human companionship.

Uhha tried to tear herself free from his grasp. She struggled like a little lion-cub, and at last would have raised her voice in a wild scream for help had not Miranda suddenly clapped his palm across her mouth, lifted her bodily from the ground and running swiftly across the clearing disappeared into the jungle.

Behind them the warriors of Obebe the cannibal slept in peaceful ignorance of the sudden tragedy that had entered the life of little Uhha and before them, far out in the jungle, a lion roared thunderously.

CHAPTER II

Three persons stepped from the veranda of Lord Greystoke’s African bungalow and walked slowly toward the gate along a rose embowered path that swung in a graceful curve through the well-ordered, though unpretentious, grounds surrounding the ape-man’s rambling, one-story home. There were two men and a woman, all in khaki, the older man carrying a flier’s helmet and a pair of goggles in one hand. He was smiling quietly as he listened to the younger man.

“You wouldn’t be doing this now if mother were here,” said the latter, “she would never permit it.”

“I’m afraid you are right, my son,” replied Tarzan; “but only this one flight alone and then I’ll promise not to go up again until she returns. You have said yourself that I am an apt pupil and if you are any sort of an instructor you should have perfect confidence in me after having said that I was perfectly competent to pilot a ship alone. Eh, Meriem, isn’t that true?” he demanded of the young woman.

She shook her head. “Like My Dear, I am always afraid for you, mon père,” she replied. “You take such risks that one would think you considered yourself immortal. You should be more careful.”

The younger man threw his arm about his wife’s shoulders. “Meriem is right,” he said; “you should be more careful, Father.”

Tarzan shrugged. “If you and mother had your way my nerves and muscles would have atrophied long since. They were given me to use and I intend using them—with discretion. Doubtless I shall be old and useless soon enough, and long enough, as it is.”

A child burst suddenly from the bungalow, pursued by a perspiring governess, and raced to Meriem’s side.

“Muvver,” he cried, “Dackie doe? Dackie doe?”

“Let him come along,” urged Tarzan.

“Dare!” exclaimed the boy, turning triumphantly upon the governess; “Dackie do doe yalk!”

Out on the level plain, that stretched away from the bungalow to the distant jungle the verdant masses and deep shadows of which were vaguely discernible to the northwest, lay a biplane, in the shade of which lolled two Waziri warriors who had been trained by Korak, the son of Tarzan, in the duties of mechanicians, and, later, to pilot the ship themselves; a fact that had not been without weight in determining Tarzan of the Apes to perfect himself in the art of flying, since, as chief of the Waziri, it was not mete that the lesser warriors of his tribe should excel him in any particular. Adjusting his helmet and goggles Tarzan climbed into the cockpit.

“Better take me along,” advised Korak.

Tarzan shook his head, smiling good-naturedly.

“Then one of the boys, here,” urged his son. “You might develop some trouble that would force you to make a landing and if you have no mechanician along to make repairs what are you going to do?”

“Walk,” replied the ape-man. “Turn her over, Andua!” he directed one of the blacks.

A moment later the ship was bumping over the veldt, from which, directly, it rose in smooth and graceful flight; circled, climbing to a greater altitude, and then sped away in an air line, while on the ground below the six strained their eyes until the wavering speck that it had dwindled to disappeared entirely from their view.

“Where do you suppose he is going?” asked Meriem.

Korak shook his head. “He isn’t supposed to be going anywhere in particular,” he replied; “just making his first practice flight alone; but, knowing him as I do, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that he had taken it into his head to fly to London and see mother.”

“But he could never do it!” cried Meriem.

“No ordinary man could, with no more experience than he has had; but then, you will have to admit, father is no ordinary man.”

For an hour and a half Tarzan flew without altering his course and without realizing the flight of time or the great distance he had covered, so delighted was he with the ease with which he controlled the ship, and so thrilled by this new power that gave him the freedom and mobility of the birds, the only denizens of his beloved jungle that he ever had had cause to envy.

Presently, ahead, he discerned a great basin, or what might better be described as a series of basins, surrounded by wooded hills, and immediately he recognized to the left of it the winding Ugogo; but the country of the basins was new to him and he was puzzled. He recognized, simultaneously, another fact; that he was over a hundred miles from home, and he determined to put back at once; but the mystery of the basins lured him on—he could not bring himself to return home without a closer view of them. Why was it that he had never come upon this country in his many wanderings? Why had he never even heard of it from the natives living within easy access to it. He dropped to a lower level the better to inspect the basins, which now appeared to him as a series of shallow craters of long extinct volcanoes. He saw forests, lakes and rivers, the very existence of which he had never dreamed, and then quite suddenly he discovered a solution of the seeming mystery that there should exist in a country with which he was familiar so large an area of which he had been in total ignorance, in common with the natives of the country surrounding it. He recognized it now—-the so-called Great Thorn Forest. For years he had been familiar with that impenetrable thicket that was supposed to cover a vast area of territory into which only the smallest of animals might venture, and now he saw it was but a relatively narrow fringe encircling a pleasant, habitable country, but a fringe so cruelly barbed as to have forever protected the secret that it held from the eyes of man.

Tarzan determined to circle this long hidden land of mystery before setting the nose of his ship toward home, and, to obtain a closer view, he accordingly dropped nearer the earth. Beneath him was a great forest and beyond that an open veldt that ended at the foot of precipitous, rocky hills. He saw that absorbed as he had been in the strange, new country he had permitted the plane to drop too low. Coincident with the realization and before he could move the control within his hand, the ship touched the leafy crown of some old monarch of the jungle, veered, swung completely around and crashed downward through the foliage amidst the snapping and rending of broken branches and the splintering of its own wood-work. Just for a second this and then silence.

Along a forest trail slouched a mighty creature, manlike in its physical attributes, yet vaguely inhuman; a great brute that walked erect upon two feet and carried a club in one horny, calloused hand. Its long hair fell, unkempt, about its shoulders, and there was hair upon its chest and a little upon its arms and legs, though no more than is found upon many males of civilized races. A strip of hide about its waist supported the ends of a narrow G-string as well as numerous rawhide strands to the lower ends of which were fastened round stones from one to two inches in diameter. Close to each stone were attached several small feathers, for the most part of brilliant hues. The strands supporting the stones being fastened to the belt at intervals of one to two inches and the strands themselves being about eighteen inches long the whole formed a skeleton skirt, fringed with round stones and feathers, that fell almost to the creature’s knees. Its large feet were bare and its white skin tanned to a light brown by exposure to the elements. The illusion of great size was suggested more by the massiveness of the shoulders and the development of the muscles of the back and arms than by height, though the creature measured close to six feet. Its face was massive, with a broad nose and a wide, full-lipped mouth, the eyes, of normal size, being set beneath heavy, beetling brows, topped by a wide, low forehead. As it walked it flapped its large, flat ears and occasionally moved rapidly portions of its skin on various parts of its head and body to dislodge flies, as you have seen a horse do with the muscles along its sides and flanks.

It moved silently, its dark eyes constantly on the alert, while the flapping ears were often momentarily stilled as the woman listened for sounds of quarry or foe.

She stopped now, her ears bent forward, her nostrils, expanded, sniffing the air. Some scent or sound that our dead sensitory organs could not have perceived had attracted her attention. Warily she crept forward along the trail until, at a turning, she saw before her a figure lying face downward in the path. It was Tarzan of the Apes. Unconscious he lay while above him the splintered wreckage of his plane was wedged among the branches of the great tree that had caused its downfall.

The woman gripped her club more firmly and approached. Her expression reflected the puzzlement the discovery of this strange creature had engendered in her elementary mind, but she evinced no fear. She walked directly to the side of the prostrate man, her club raised to strike; but something stayed her hand. She knelt beside him and fell to examining his clothing. She turned him over on his back and placed one of her ears above his heart. Then she fumbled with the front of his shirt for a moment and suddenly taking it in her two mighty hands tore it apart. Again she listened, her ear this time against his naked flesh. She arose and looked about, sniffing and listening, then she stooped and lifting the body of the ape-man she swung it lightly across one of her broad shoulders and continued along the trail in the direction she had been going. The trail, winding through the forest, broke presently from the leafy shade into an open, parklike strip of rolling land that stretched at the foot of rocky hills, and, crossing this, disappeared within the entrance of a narrow gorge eroded by the elements, from the native sandstone, fancifully as the capricious architecture of a dream, among whose grotesque domes and miniature rocks the woman bore her burden.

A half mile from the entrance to the gorge the trail entered a roughly circular amphitheater, the precipitous walls of which were pierced by numerous cave-mouths before several of which squatted creatures similar to that which bore Tarzan into this strange, savage environment.

As she entered the amphitheater all eyes were upon her, for the large, sensitive ears had warned them of her approach long before she had arrived within scope of their vision. Immediately they beheld her and her burden several of them arose and came to meet her. All females, these, similar in physique and scant garb to the captor of the ape-man, though differing in proportions and physiognomy as do the individuals of all races differ from their fellows. They spoke no words nor uttered any sounds, nor did she whom they approached, as she moved straight along her way which was evidently directed toward one of the cave-mouths, but she gripped her bludgeon firmly and swung it to and fro, while her eyes, beneath their scowling brows, kept sullen surveillance upon the every move of her fellows.

She had approached close to the cave, which was quite evidently her destination, when one of those who followed her darted suddenly forward and clutched at Tarzan. With the quickness of a cat the woman dropped her burden, turned upon the temerarious one, and swinging her bludgeon with lightninglike celerity felled her with a heavy blow to the head, and then, standing astride the prostrate Tarzan, she glared about her like a lioness at bay, questioning dumbly who would be next to attempt to wrest her prize from her; but the others slunk back to their caves, leaving the vanquished one lying, unconscious, in the hot sand and the victor to shoulder her burden, undisputed, and continue her way to her cave, where she dumped the ape-man unceremoniously upon the ground just within the shadow of the entranceway, and, squatting beside him, facing outward that she might not be taken unaware by any of her fellows, she proceeded to examine her find minutely. Tarzan’s clothing either piqued her curiosity or aroused her disgust, for she began almost immediately to divest him of it, and having had no former experience of buttons and buckles, she tore it away by main force. The heavy, cordovan boots troubled her for a moment, but finally their seams gave way to her powerful muscles.

Only the diamond studded, golden locket that had been his mother’s she left untouched upon its golden chain about his neck.

For a moment she sat contemplating him and then she arose and tossing him once more to her shoulder she walked toward the center of the amphitheater, the greater portion of which was covered by low buildings constructed of enormous slabs of stone, some set on edge to form the walls while others, lying across these, constituted the roofs. Joined end to end, with occasional wings at irregular intervals running out into the amphitheater, they enclosed a rough oval of open ground that formed a large courtyard.

The several outer entrances to the buildings were closed with two slabs of stone, one of which, standing on edge, covered the aperture, while the other, leaning against the first upon the outside held it securely in place against any efforts that might be made to dislodge it from the interior of the building.

To one of these entrances the woman carried her unconscious captive, laid him on the ground, removed the slabs that closed the aperture and dragged him into the dim and gloomy interior, where she deposited him upon the floor and clapped her palms together sharply three times with the result that there presently slouched into the room six or seven children of both sexes, who ranged in age from one year to sixteen or seventeen. The very youngest of them walked easily and seemed as fit to care for itself as the young of most lower orders at a similar age. The girls, even the youngest, were armed with clubs, but the boys carried no weapons either of offense or defense. At sight of them the woman pointed to Tarzan, struck her head with her clenched fist and then gestured toward herself, touching her breast several times with a calloused thumb. She made several other motions with her hands, so eloquent of meaning that one entirely unfamiliar with her sign language could almost guess their purport, then she turned and left the building, replaced the stones before the entrance, and slouched back to her cave, passing, apparently without notice, the woman she had recently struck down and who was now rapidly regaining consciousness.

As she took her seat before her cave mouth her victim suddenly sat erect, rubbed her head for a moment and then, after looking about dully, rose unsteadily to her feet. For just an instant she swayed and staggered, but presently she mastered herself, and with only a glance at the author of her hurt moved off in the direction of her own cave. Before she had reached it her attention, together with that of all the others of this strange community, or at least of all those who were in the open, was attracted by the sound of approaching footsteps. She halted in her tracks, her great ears up-pricked, listening, her eyes directed toward the trail leading up from the valley. The others were similarly watching and listening and a moment later their vigil was rewarded by sight of another of their kind as she appeared in the entrance to the amphitheater. A huge creature this, even larger than she who captured the ape-man—broader and heavier, though little, if any, taller—carrying upon one shoulder the carcass of an antelope and upon the other the body of a creature that might have been half human and half beast, yet, assuredly, not entirely either the one or the other.

The antelope was dead, but not so the other creature. It wriggled weakly—its futile movements could not have been termed struggles—as it hung, its middle across the bare brown shoulder of its captor, its arms and legs dangling limply before and behind, either in partial unconsciousness or in the paralysis of fear.

The woman who had brought Tarzan to the amphitheater rose and stood before the entrance to her cave. We shall have to call her The First Woman, for she had no name; in the muddy convolutions of her sluggish brain she never had sensed even the need for a distinctive specific appellation and among her fellows she was equally nameless, as were they, and so, that we may differentiate her from the others, we shall call her The First Woman, and, similarly, we shall know the creature that she felled with her bludgeon as The Second Woman, and she who now entered the amphitheater with a burden upon each shoulder, as The Third Woman. So The First Woman rose, her eyes fixed upon the newcomer, her ears up-pricked. And The Second Woman rose, and all the others that were in sight, and all stood glaring at The Third Woman who moved steadily along with her burden, her watchful eyes ever upon the menacing figures of her fellows. She was very large, this Third Woman, so for a while the others only stood and glared at her, but presently The First Woman took a step forward and turning, cast a long look at The Second Woman, and then she took another step forward and stopped and looked again at The Second Woman, and this time she pointed at herself, at The Second Woman and then at The Third Woman who now quickened her pace in the direction of her cave, for she understood the menace in the attitude of The First Woman. The Second Woman understood, too, and moved forward now with The First Woman. No word was spoken, no sound issued from those savage lips; lips that never had parted to a smile; lips that never had known laughter, nor ever would.

As the two approached her The Third Woman dropped her spoils in a heap at her feet, gripped her cudgel more firmly and prepared to defend her rights. The others, brandishing their own weapons, charged her. The remaining women were now but on-lookers, their hands stayed, perhaps, by some ancient tribal custom that gauged the number of attackers by the quantity of spoil, awarding the right of contest to whoever initiated it. When The First Woman had been attacked by The Second Woman the others had all held aloof, for it had been The Second Woman that had advanced first to try conclusions for the possession of Tarzan. And now The Third Woman had come with two prizes, and since The First Woman and The Second Woman had stepped out to meet her the others had held back.

As the three women came together it seemed inevitable that The Third Woman would go down beneath the bludgeons of the others, but she warded both blows with the skill and celerity of a trained fencer and stepping quickly into the opening she had made dealt The First Woman a terrific blow upon the head that stretched her motionless upon the ground, where a little pool of blood and brains attested the terrible strength of the wielder of the bludgeon the while it marked the savage, unmourned passing of The First Woman.