9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

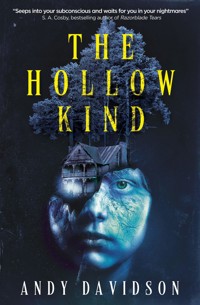

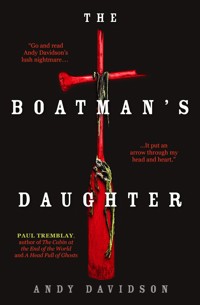

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Ever since her father was killed when she was just a child, Miranda Crabtree has kept her head down and her eyes up, ferrying contraband for a mad preacher and his declining band of followers to make ends meet and to protect an old witch and a secret child from harm. But dark forces are at work in the bayou, both human and supernatural, conspiring to disrupt the rhythms of Miranda's peculiar and precarious life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 443

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

I In a Certain Kingdom, in a Certain Land

II First Run

Upriver

Sabbath House

Signs and Wonders

Littlefish

The Language of Family

The Heart

Crabtree Landing

Rooding

Digging

In the Land of Spain

III Second Run

In His Tree, Littlefish Dreaming

The Trade Tonight

It’s in the Mouth

Choices

What the Girl Saw, On the Prosper

Faith

Arrangements

Billy Cotton

Not the Least Among Them

Licorice

I Used to Be Handsome

Bathhouse

Bannik

Sunlight

Hand in Hand

Secrets

Sharp

Aim

No Shelter Here

All There Is

Into the Woods

Interruption

IV Final Run

Cargo

At the Camp

Avery and Miranda

Cotton On the River

The Men Who Killed Cook

Safe

Trestle and Fire and Water

The Lord’s Business

The Girl, in A Tower

The Blood-Sprinkled Way

Miranda and the Giant

Iskra’s Path

A By-God Devil

A Cold Camp

Ice Cream

V Revelations

The Nature of Friendship

Wall

Miranda At the Cabin

Teia Goes to Church

Lost

The Father Hen’s House

Through the White

The Greenhouse

The Edge of the Abyss

Tremors and Eclipse

Rock and Tree and Monster

Fault

Miranda in the Tree

Arrow and Cross

The Land Will Tell You A Story

Riddle At the Window

Cotton Takes A Bath

The Plan

The Constable Investigates

Alive

A Problem in the Trunk

Ready

Reach

Avery

Ritual

Teia in Trouble

In the Master Bath

Look and See

The Constable, Screaming

What Miranda Saw

Go

Last Breath

The Boy, Not Alone

To the River, to the End

Lena

Her Brother’s Trail

Shadow and Root and Stone

Fire and Flood

VI After the Flood

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Boatman’s Daughter

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095999

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096002

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: October 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Andy Davidson 2020. All Rights Reserved.

Andy Davidson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Mom and Dad

... what’s past is prologue ...

—The Tempest

Now, Myshka, I will tell you the truth. Let my voice bury my words deep inside you. Before the sun sets, I will tell you secrets you have longed to know. For I was a girl once, too, and like you, I have known sorrows so great there are no words to account for them.

I

In a Certain Kingdom, in a Certain Land

IT WAS AFTER MIDNIGHT WHEN THE BOATMAN AND his daughter brought the witch out of Sabbath House and back onto the river. Old Iskra sat astride the johnboat’s center plank, wearing a head scarf and a man’s baggy britches damp with blood, their iron reek lost to the night-fragrant honeysuckle that bowered the banks of the Prosper. In her lap: a bread bowl, wide and deep and packed with dried eucalyptus sprigs and clods of red earth broken around a small, still form covered by a white pillowcase. The pillowcase, like the old woman’s clothes, stained red.

They angled off-river at the mouth of a bayou and were soon enclosed by the teeming wall of night. Cries of owls, a roar of bullfrogs, the wet slopping of beaver among the stobs. Miranda Crabtree faced into the wind, lighting Hiram’s way with the Eveready spot mounted on the bow. The spotlight shined on branches closing in, cypress skirts scraping like dry, bony fingers along the johnboat’s hull. Spiders in the trees, their webs gleaming silver. A cottonmouth moccasin churning in the shallows. Miranda held up arms to guard her ears and cheeks from the branches, thinking of Alice down the rabbit hole, one small door opening upon another, and another, each door smaller than the last.

“Push through!” the old witch cried.

Branches screeching over metal, they did, the boatman breaking off fistfuls of dead cypress limbs until the boat slipped free onto the wide stage of a lake. Here, Hiram cut the motor and they drifted in a stump field, a preternatural silence descending over frog and cricket and owl, as if the little boat had somehow passed into the inner, sacred temple of the night itself.

To the west, purple lightning rolled thunderless in the cage of the sky.

In the water were the twisted, eerie shapes of deadfalls. They broke the surface like coffins bobbing in flooded graves.

“What is this place?” Miranda asked, angling her light all around.

But no one answered.

Ahead, a wide muddy bank stretched before a stand of trees, tall and close, and when the boat had nosed to a stop in the silt, the old witch got up with a pop of bones, stepped over the side, and staggered off along the path of the light, bowl in her arms. Her shadow long and reaching.

Hiram brought up a shotgun and a smaller flashlight from behind the stern seat. Miranda knew the double-barrel to be her grandfather’s, the only gun Hiram had ever owned. She had never seen him fire it. They were bowhunters, the Crabtrees. Always had been.

“She needs me to go with her,” he said. “You stay put.”

“But—”

He stepped out of the boat into the mud and came around to the bow, where Miranda could see his face in the light. Long and narrow, sadness in his very bones, it seemed, the first touches of gray at his temples. Drops of moisture swirled thick in the light between them.

“Stay,” he said. “The light will guide us back.”

He took her chin in hand and brushed her cheek with his knuckles and told her he loved her. This frightened Miranda, for these were not words Hiram Crabtree often said. They struck her now like a kind of incantation against something, some evil he had yet to fathom. He kissed the back of her hand, beard rough against her skin. He said he would be back. He promised. “Leave that light shining,” he said, and then he left her, following the witch’s humped form into the trees. Their deep tracks welling up with water, as if the land itself were erasing them.

* * *

The spring night grew hushed save for the far-off mutter of the coming storm, which had been threatening since twilight, black clouds like a fleet of warships making ready to cannonade the land with fire, water, wind, and ice.

Hours before, when Hiram woke her, Miranda had been dreaming of stumbling through woods and brambles onto a path that brought her out of the trees and into a clearing, where the land sloped up to a hilltop draped in flowering kudzu, little white blossoms aglow in the moonlight. Cradled in her arms, a black bullhead catfish she had only just pulled slick and dead from the bayou. Atop the hill: the witch’s cabin on stilts, one yellow flame burning in a window. Miranda went up the crooked, red-mud path, up the wide board steps of the porch, and into the cabin, where the old witch stood waiting. She dropped the fish in the old woman’s bread bowl and the witch took her filleting knife from her apron and slit the fish’s belly. Miranda put her thumbs in the fish’s gills to lift it and the innards slopped out in a purple heap. The old witch slung the guts into her boxwood stove, where they hissed and popped in the fire, and the dead fish heaved in Miranda’s hands, came alive, began to scream. It screamed with the voice of a child.

Then Hiram’s hand on her shoulder, shaking her.

Now, in the johnboat, she was waiting. Chin in hand, elbow on her knee, just as she had sat waiting earlier that night on the porch steps of Sabbath House. They had fetched the witch from her cabin on the bayou, and from there upriver to that ugly, paintlorn manse.

The front door of the plantation house stood open to let in the cool, blustery air. Last fall’s leaves skittered over the boards like giant palmetto bugs as, inside, the witch went about her ancient trade behind a shut bedroom door. Across the gravel lane, Hiram stood in the bald, root-gnarled yard of a low shotgun house, talking softly to a man who was not quite five feet tall. The little man listened intently, head down, hands in his pockets. Windows of the other five shacks that stood beneath the trees were lit, a few men smoking anxiously between the clapboard dwellings, just beyond the reach of their own bare-bulb porch lights. Vague, grown-up shapes to Miranda.

Within the manse, a woman screamed, freezing every soul who heard.

Another scream: the wail of something deep and true torn loose, lost to the dark.

Hiram and the dwarf went charging past Miranda into the foyer, only to halt in shock at the foot of the stairs. Miranda pushed between them and saw an old man, all legs and elbows in black suit pants and a bloody white shirt, stagger out of the bedroom to sit like a broken toy at the top of the stairs. He clutched in his hands an object, something Miranda could not see, forearms red with blood up to his cuffs, which were rolled at the elbows. Miranda felt her father’s hand on her shoulder, and when she looked up she saw Hiram’s face gone pale as chalk. The little man to her right was stout and strong, but she glimpsed it on his face, too: horror.

The witch came solemnly out of the bedroom. Carrying the bread bowl. She passed the old man on the stairs, whose eyes never strayed from whatever faraway place they had fixed.

Blood dripping on the boards between his scuffed wing tip shoes.

Hiram pushed Miranda toward the front door, and she glimpsed, off the foyer in the downstairs parlor, a man sitting on an antique sofa. He was young, slim, handsome, a lit cigarette between full lips and a glass of amber liquid in hand. He wore a gun, a badge.

He winked a cornflower-blue eye as Miranda scooted past.

* * *

Now, in the johnboat. Waiting still, picking at a scab on her bare knee.

Thunder boomed, closer.

Straight ahead, a white whooping crane stepped out of the trees into the Eveready’s beam. It stood in the mud and seemed to glow, stark and bright and otherworldly against the black of the swamp. Miranda watched it, and it watched her. The spotlight’s beam like a tether between two worlds, Miranda’s and the bird’s. Something preternatural crept up her spine, raised gooseflesh on her arms.

A slow, rolling rumble that wasn’t thunder came out of the trees, and the crane launched itself into the dark.

The water in Hiram’s bootprints rippled, and Miranda felt the aluminum boat shudder.

The distant trees swayed in their tops, though the air was heavy and still.

Miranda’s heart pounding in her chest.

Then, deep within the woods: a gunshot.

It cracked the night in two.

A second shot followed, reverberating huge and canyonlike.

Miranda drew a single breath, then leaped from the boat. The mud yanked her down, but she struggled up and ran for the trees, forgetting that the Eveready at the bow shone only so far. In the woods, darkness reared up and closed her between its palms. She skidded to a halt.

Called for Hiram. Listened.

Called again.

Heart racing, blood pounding, shore and spotlight at her back, she ran.

Lightning flashed at close intervals, lit the trees bright as day.

She ran on, calling out until Hiram’s name was no longer a word, just a raw, ragged sound. She struck a tree, bounced, came up hard against another, and there she hung against the rough bark, gasping.

More lightning, and in that staccato flash, the land sloped down to a maze of saw palms wrapped in shreds of mist. Beyond the maze, the undergrowth rose up in a tangled, briar-thick wall, impenetrable. Great thorny vines, woven tight as a bird’s nest.

Shining deep within that nest, like a string she had followed from boat to forest, was the faint orange beam of a flashlight. Fixed and slanting across the ground. All but swallowed by the darkness.

Miranda staggered into the saw palm maze, blades nicking her bare arms and legs. She felt the wisp of orb weavers against her cheeks, webs enshrouding her as they broke against her, as if nature were clothing her in itself, preparing her for some arcane ritual. When the fronds grew too close, she went down on hands and knees and crawled in the moist earth, and the light ahead grew stronger, closer. When she finally reached the undergrowth, she saw a kind of tunnel through it, just large enough for a fox or a boar—or a girl. She pressed her belly to the ground and worked elbows and hips and legs to worm through the thick tangle, aware a sound was coming out of her, some primal grunt that made her think she might vomit up the whole of her insides and there, in the sticky pink folds of stomach, would be a pile of stones, the source of this grunting, clacking noise. Finally, she came out where Hiram’s flashlight lay bereft in a clump of moss and pale, fleshy toadstools.

“Daddy,” she was gasping, “Daddy.”

The glass of the lens and the blue plastic housing crawled with bugs.

Covered in mud and spider silk and tiny rivulets of blood, the squished remnants of a green-backed orb weaver stuck like a barrette in her dark hair, Miranda took up the light and got to her feet. She called again for Hiram, sweeping the beam over bare, bone-white trees, like great spears hurled down into the earth. Clumps of marshy reeds rising out of black pools that sheened in the light like oil. Narrow, mossy strips of earth among the pools.

And something else, too, glimpsed in the lightning, just beyond the trees.

Miranda went carefully alongside one of the pools that branched into a stream, black and thick. Moss along the bank festooned with brown toadstools and odd, star-shaped plants she had never seen the like of in all her trips hunting, fishing, trapping with Hiram. Sticks and clumps of bark were lodged in the stream and blackened, and at what appeared to be the widest, deepest point, her light caught the shape of something large and half submerged on its side. Brown feathers speckled black. An owl.

The stream opened out into a kind of moat that circled a great wide clearing, and at the center of the clearing was the thing she had glimpsed in the lightning. A shape, huge and dark and shrouded in mist. Peering up at it, Miranda saw what looked like a head, two great horns, and two long ragged limbs ending in crooked fingers. She almost cried out, even took a step back. Then realized, in the rapid shutter of the lightning, that it was only a shelf of rock, atop it a tree, thick and twisted and dead, its trunk canting out at an angle that should have sent it tumbling from the ledge into the muck below.

A bark-skinned log bridged the black moat that encircled the rock. Miranda crossed it, balancing as she went. Sweat soaked through her shirt, her underwear. The earth beyond the moat was spongy, soft, rich. She felt it sinking underfoot with every step. She went through clumps of reeds and grass and played her light up at the rock as she came into its shadow and saw a long branch reaching like an arm from the tree, and from this arm a thick vine dropped straight down like a plumb line into a mound of freshly turned black earth, at its center a hole, deep and dark. The opening big and wide as a tractor wheel.

Among a stand of thin brown reeds at the base of the mound: the old witch’s bread bowl, drawn in blood, overturned. A pillowcase in the dirt.

Miranda heard a snap in the dark, a squelch from near the rock.

Eyes were on her, she could feel them.

Bugs crawled over Hiram’s light.

Her voice small and swallowed by the night: “Daddy?”

She played the light over the distant rock, its cold surface shining back, a tangle of fat roots and vines like a fall of wet hair. Her beam caught something in the mud, a glint of brass. She went to it, bent, and plucked up the red wax casing of a shotgun shell. She touched it to her nose, smelled the acrid scent of gunpowder still fresh on it. She knocked bugs from the light and cast about for Hiram’s blood, a second shell, some track or sign.

Nothing.

She pushed the shell into the pocket of her shorts.

A rustling, in the clump of grass near her feet.

Miranda swung the light.

Something round and red and raw lay in the moss, not far from the upended bowl. At first Miranda didn’t recognize it. Slicked with gore, more like a skinned rabbit than a baby. Its flesh a lifeless gray. She played the beam over arms and legs. They were mottled, rough and scaled, a long white worm of umbilicus twisted beneath it. Leaves clinging to a head of dark hair.

Its belly heaved. Its mouth opened.

For an instant, she did not move. Then she ran to it, dropped on her knees beside it.

Below its chin, a wide slit bubbled fresh bright blood like a second mouth as the baby gulped and sucked air.

She saw the pillowcase among the reeds and stooped for it, not looking where she was stepping. She splashed into a shallow pool of black liquid, thick and warm. It flooded her shoe, soaked her sock. Miranda gasped as her foot began to tingle, then to burn. Working quickly, ignoring her foot, she turned the pillowcase inside out and used a clean edge to press the wound at the baby’s throat. But now it seemed it was not a wound at all, for the blood wiped free and the flesh there, beneath the jaw, was whole.

Had she imagined it? Some trick of shadow and gore?

She wiped her hand on her shorts, snakes of adrenaline still in her fingers as she worked her thumb into the baby’s old-man palm and the digits parted. Between each digit was a thin membrane of skin, purple veins alight in the glow of Hiram’s flashlight.

Webbed—

A sudden rustle from the reeds where she’d found the pillowcase.

A whiplike blur, pink tissue and fang.

She felt the sound: a tenpenny nail punching flesh.

Shocked, she fell back on her haunches. Barely caught a glimpse of it, fat and long, the color of mud. A cottonmouth, corkscrewing away.

. . . snake-bit, oh, oh, Daddy, no. . .

. . . she grabbed the flashlight, shined it on her left forearm, saw the wound welling blood, the flesh already puffing . . .

. . . stay calm, keep your heart rate down, the boat, the baby. . .

One last clamor of thunder and the rain began to fall. Big fat drops, cold and stunning.

Oh, oh no, Daddy, I’m sorry. . .

Miranda staggered to her feet, picking up the baby in her right arm, holding the flashlight with her left, right foot gone numb from the sludge that slicked it, and set off back in the direction she had come.

At the tunnel she fell to her knees, heart racing, sluicing venom, head fuzzy.

The flashlight went tumbling. Lost.

Crawling now, pushing through, slow, so slow, the numbness in her left arm reaching her shoulder, the tingling in her foot inching higher, into calf and thigh, her whole body assaulted, long thorns snagging her shirt and hair, and all the while the baby’s heart hammering against her own, a fish odor wafting up.

Upright again, lurching—

Left arm tight against her side, stumbling, sharp fronds slicing, right leg numb from the hip down now, oily black sludge burning skin—

She fell.

She lay on her back and the rain pelted her face, ran beneath her in tiny rivers.

The fingers of her left hand swollen thick as corks.

The baby lay at her small, girl’s breast. Alive but weak.

You are going to die tonight, Miranda Crabtree thought, staring up at the dark boughs of the trees, where the lightning made jagged shapes and turned the trees into devils come to minister. This is your death.

She had a sudden urge to taste the black licorice they kept in jars to sell. Catfish bait, the old-timers who came to the mercantile called it.

Oh, Daddy, where are you, I am sorry, Daddy, so sorry I was not clever. . .

The rain was hard and cold and numbing.

Then, from the dark recesses of the trees behind her, a terrible rumble, the boughs overhead thrashing. From the forest all around a cracking, a rending, as trees tore free from the earth and hurled themselves to the ground, and a wind blasted the cold rain sideways so that it seemed the breath of a huge thing was blowing over Miranda, and with the wind came a bright piney scent of fresh resin that stung her nostrils, and yes, something massive, something dark and horned and snarling and impossible, emerging now from the trees—

Not real, it’s not real

—to lift her up in its terrible, rough-bark hand, entwining vines around arm and waist and leg, setting her afoot and nudging her over wet ground, stomach turning, hair wet against her scalp, and a fever burning in her arm and head.

Feeling had returned to her leg, she realized, the burning from the black sludge subsided, so she staggered off, soaked through, the baby against her breast chilled and silent.

Eventually there was a light, a pinhole in the darkness, and at first she thought it was the light to bring her over to another land, to the place her mother, Cora Crabtree, had gone long ago, when Miranda was only four. But it was not. She looked around and saw she stood mired in the muddy shore, where her footprints, like Hiram’s, like the old witch’s, were filled with water and led back to the place where the johnboat was lodged in the mud, Eveready spot still shining from the bow.

To guide us back.

But she saw no boatman in the lightning, no witch in its glare, and her left arm was hot and hard like a length of stovewood despite the cold, cold rain. She spoke her father’s name. A whimper. Tears. Retching. Vomit. She collapsed in the mud, lay over on her back and let the baby rest atop her, right hand cupped around its weakly pulsing fontanel.

Out of the dark, into the weak beam of the boat light, a stooped shape came, small and hunched and peering down. Smooth chin and black eyes glittering within a head scarf. In one hand, Hiram Crabtree’s shotgun, in the other an empty, bloody bread bowl.

Thunder, the whole world booming.

I’m only eleven, Miranda thought, fading. I don’t want to die—

She felt the baby’s weight against her, its faint warmth a promise.

She closed her eyes. Darkness took her.

* * *

The storm poured down ruin upon the land. Indeed, it was a storm the people of Nash County, Arkansas, would remember for years to come. It raged like a thing alive. On the outskirts of the defunct sawmill town of Mylan, the painted women of the Pink Motel stood watching the rain like forgotten sentries from their open doorways, the night’s business washed away. They smoked cigarettes and hugged themselves as hailstones broke like bullets against the weed-split parking lot. The older women turned away, shut their doors, drew curtains. The young remained watchful, restless, eyes fixed, perhaps, on the position of some faraway star they had long looked to, now obscured by the storm. Miles south, where the land became a warren of gravel roads twisting back upon themselves, where the sandy banks of the Prosper gave way to stumps and sloughs, bottom dwellers came out onto the porches of shanties, long-limbed men in overalls and rail-thin women in cotton shifts. Children not clothed at all. They watched the rain pour from the eaves of their tin roofs to wear away the mud below and saw in this the promise of their own slow annihilation, their fates tied inextricably to the land they or some long-lost forebear had claimed.

And finally, along the river’s edge, the congregants of Sabbath House, numbering no more than a dozen souls, this clutch of ragged youth sheltering not from the raging heavens but from the terror that was their mad, lost preacher Billy Cotton, who even now sat soaked in the blood of his dead wife and child in the old manse across the lane. Their numbers ever dwindling since the madness had first bloomed in the old man years past, they huddled in the little row of shotgun houses as the wind howled and pine branches cracked and fell to lodge like unexploded bombs in the earth. They prayed, some of them. Others wept. Come the morning, surely they would all be gone.

* * *

Inside the manse, the old preacher sat unmoving on the stairs, even as a great oak bent and crashed into the western wall, shattering glass and stoving in the copper-sheeted roof. Billy Cotton’s mouth was dry, his tongue like sandpaper. His heart ticked steady as a clock. The object in his bloody hands—what the boatman’s curious daughter had not seen—was a pearl-inlaid straight razor, closed. Outside, the wind roared like a great cyclone come to funnel the old preacher up and away, and now as the water began to strike him he looked up through the hole at the sky above and saw lightning crack like God’s own judgment of his sins. And so he stood and went down the steps with his razor in hand, down the gravel lane and out onto the rickety dock that jutted over the stagnant water that flowed off the Prosper, where the boatman had brought the witch to deliver his child, and the child had been a monster, an abomination Cotton had held aloft by the ankle to show it to the twisted, pain-ravaged face of its mother, who would have loved it had she lived, because how could she not, this woman he had once given his heart to, whose pity and voice had moved mountains, and so the razor flashed in the gleaming light from the bedside lamp, and the old witch watched him draw it sharply, quickly. And did nothing, because she knew, as he did, that it was monstrous, this thing, this child that was not a child. And now, here, at the end of the dock, he closed up the razor that had been his since the days of his youth in a Galveston orphanage and hurled it into the water and fell to his knees and began to weep, great racking sobs, and soon he lay prostrate, bereft, a wailing banshee slicked in blood and rain, and after a while he curled up on his side and slept there on the boards, and soon the storm abated, and the air grew fresh and cool, and the dark rose up in a chorus of frog song.

II

First Run

UPRIVER

COOK HUNKERED AT THE BOTTOM OF THE RAMP, LET his fingers play in the slow-moving Texas water. Downstream, just beyond where the river became Arkansas, a train traversed a trestle bridge, tearing through the last lingering rag of night. He could almost read the graffiti on the boxcars. The sound of it put him in mind of an old song, something about a baby in a suitcase, thrown from a train, the woman who raised it. In forty-nine years of life, Cook had never ridden a train, and the woman who had raised him was long dead. He scratched his beard. Put his fingers back in the moving water, liked the feel of it flowing on, the river indifferent to his presence. The world needed nothing of him to keep on spinning.

He checked his watch: 5:12 a.m.

The train had been gone only a few minutes when he heard, downriver, the Crabtree girl’s boat.

He trudged back up the short ramp, over corrugated and broken concrete, to where his Shovelhead was parked. The road leading into the clearing was old gravel, long disused and grown over with Bahia grass. On a patch of ground where the grass was worn were the long-ashed bones of a fire. The woods beyond the clearing dark yet, the only light a blue mercury-vapor lamp shining at the edge of the trees. Cook took two longnecks from his saddlebag and popped each with a bottle opener on his key chain. Down the ramp, he saw her, rounding the bend in her Alumacraft, the trestle long and dark above. Cook lifted a hand, and she raised her own. She pointed at the old flat barge tethered along the bank, just up from the ramp. He walked down to it, through shin-high weeds, toes of his boots getting damp with dew.

The barge had been there as long as Cook could remember, rotting but never sinking. Parts strewn across the deck as if the vessel were mid-repairs when abandoned: a rusted inboard engine, gaskets, water pump and solenoid, all beyond good use.

The girl tied the Alumacraft to a starboard cleat.

Cook waited, holding the beers in one hand behind his back, as if they were flowers.

She bent to pick up her blue Igloo cooler and was about to board the barge when she saw his hand, hidden. She tensed. He held out the beers, waggled the bottles. She gave him a look and set her Igloo onto the barge and came aboard.

They sat cross-legged against the wheelhouse with its busted windows and graffitied walls, drinking, listening to the slow current of the Prosper, the distant whir of Whitman Dam four miles upriver. Beyond the dam the lake, and beyond the lake a hundred more miles of greenish brown water running south from northeast Texas like a scar on the land, cut eons ago when fossils were fish and the whole of the country was a Jurassic sea where great behemoths swam. Now, birdsong in the maples and oaks and beeches, the day coming alive.

Cook stole glances at the girl in the graying light. Her profile was sharp and long, like the rest of her, scattershot freckles across nose and cheeks, a few acne scars like slash marks across her chin. Her jaw was hard and set. Dark hair pulled back, tidy but unwashed. Her eyes a murky gray-green. She had cut things out of herself to survive on the river, as a man cuts free a hook barbed deep in his flesh. There were words for what she did not lack: grit, mettle. What it took to carve up an animal, to cut through bone and strip skin and scoop viscera with bare hands, to wipe away sweat and leave behind a streak of blood. She did not lack these things.

She’d see it coming, surely.

The end.

Perhaps already had.

She caught him watching her. Fidgeted, then finished her beer in three long swallows and tossed the bottle over her shoulder, through the broken wheelhouse window. The bottle clipped a shard of glass and the sound of it breaking was loud and jarring. She got up, dusting the loose seat of her jeans, and made a business of ignoring Cook. Stepped back into her boat, checked her fuel. Picked up a metal can and tipped it into the motor’s tank.

He drained his bottle, tossed it into the weeds along the shore, and tromped off the barge and up the ramp, back to the Shovelhead, where he fetched his bedroll with the money wrapped inside. By the time he returned, she was on the deck of the barge again, hands on the small of her back, stretching and staring at the distant silhouette of the railroad trestle. Cook took a knee by her cooler. He untied his roll and spread it on the deck. Tossed her the cash in a rolled lunch sack that lay at the bedroll’s center like the meat of a nut. Her lips moved silently as she counted it. Cook peeled the duct tape from around the Igloo’s lid and took out the dope and laid it all in a row on the roll: eight pint canning jars, stuffed full and sealed. These he rolled in a serape, then rolled the serape into the sleeping bag.

When he was done, the girl dropped the paper sack into the Igloo and closed it and made to pick up the cooler.

“Wait,” Cook said. He reached out, took her wrist gently.

She jerked back, studied him.

Searching, he knew, for some clue she had overlooked these last seven years, since the very first run. Any truth that could hurt or trap her. Cost her something she was not willing to pay. He held up his hands, palms out, an apology.

She just stood there, looking at him. Suspicious as a cat.

“I’ve got something else for you,” he said.

Wanting to add: It’s all been leading here, ever night since the first, when you were fourteen and came piloting that big boat alone.

He reached to the small of his back and brought out a pistol from his waistband.

She froze.

He flipped it, held it out flat on his palm like an offering between them.

“Smith and Wesson snub-nose,” he said. “Good close up, if it comes to it.”

She stared at him, unreadable as stone.

“Take it,” he said. “Learn to use it. Bring it next time. Keep it out of sight, but you bring it, hear?”

“Why?” she said, making no move to take the gun.

He set the revolver down on the barge between them and cinched each end of his bedroll with a rawhide cord. “Because,” he said quietly. “Maybe one day the man says do this one particular thing for the preacher and I say no, it ain’t the kind of thing I do. I truck in dope, that’s all. A man trucks in innocence—” He swallowed. Shook his head. “They put you under for things like that. If I’d known they’d ask me to, maybe I never would have . . .”

He lapsed, staring off into the river, which flowed quietly on, implacable.

“Gets you thinking,” he said, more to himself now than her. “What are you willing to do? Where’s the end of it?”

A muscle in her jaw ticked. She looked away.

Cook stood and shouldered his roll. He left the pistol on the rusted metal deck of the barge. “They’ll ask you to make another run,” he said. “Maybe one more, maybe two, I don’t know. It’s the last one you best worry about, savvy?”

The dawn had almost fully broken around them.

Her answer was barely audible, but Cook heard it. He always heard her, no matter how low she spoke, and she was in the habit of speaking very low.

“Crabtrees don’t use guns,” she said. She took the Igloo and hopped from the barge into her boat, leaving the pistol on the deck.

So he picked it up and did something that he had not done in all the time he had known her. He called her by name, and just speaking the word was enough to turn her head, if only for a moment, but it was a moment that would hang between them forever, so long as one of them lived. The morning mist curling up from the river like wood shavings. “Miranda,” he called, and when she turned, he tossed her the gun.

She caught it, a reflex. Held it in both hands.

He thought about what he might say next. He wanted to tell her what knowing her had meant, how every few months he grew restless not seeing her and did not know why. That she was a mystery and a magic in his life. But words like these had never come easy to Cook, so instead he just said, “Tell that dwarf to watch out for himself. We was friends. I reckon he’ll understand.”

A shadow of something—doubt, fear—crossed her face. But it was gone, just as quickly as it came, and after it had passed she tossed the gun carelessly in the bottom of her boat. She whipped the Alumacraft around and aimed it back downriver, sparing him no look, no farewell, not even a wave. As if putting distance between them as quickly as possible might erase this new, mysterious line just drawn. A border to be crossed, and she, retreating from it.

Least she took the gun, Cook thought. That’s something.

He walked back up the ramp and stood at the top, listening, until the sound of her motor had faded.

He had just kicked the Shovelhead to life—it snarled and spat—when a wave of loss so profound washed over him that he slumped on the seat. He looked one last time at the muddy river, where the only mystery left in his life had just disappeared, she, perhaps, fully ignorant of the empty wake her passing had left in his heart.

He rode his bike out of the woods and down the long, straight gravel road, which ran parallel to the train tracks for a time, a field of grain sorghum stretching away on the left in the amber light of morning.

Maybe I will buy myself a big silver Airstream and a truck to haul it, and I will head west. Way out west—

Ahead, where gravel met asphalt, a white Bronco was turned crosswise, and two men clad in T-shirts and denim stood outside it. One—short, pale-skinned, bald—looked down the road at Cook through a pair of binoculars. The other—huge and hulking—held a scoped rifle. Cook slowed, had just enough time to register what he was seeing, then caught the puff of smoke from the barrel. He never heard the shot, but he felt the impact in his chest, like a metal fist driving him backward, separating him from his bike, his daydreams, his tether to the world. He hit the gravel on his back and the bike skidded into the long grass.

Lying in the dirt, the taste of blood rising in his throat, he could not feel his body. He heard the pop of gravel under tire, heard doors slam.

A voice said, “Dope’s no good. Got glass all in it.”

He saw a giant dark shape blot out the golden sky. In its hand a blade, long and curved and wicked. A scythe.

“More where that came from,” the giant said, and raised his blade.

Cook shut his eyes.

SABBATH HOUSE

THE DWARF JOHN AVERY LEANED AGAINST A PILING AT the end of Sabbath Dock, head downcast, boots angled sideways in the weary posture of a man turning life over between his soles. He wore a pair of unwashed jeans and a wrinkled plaid shirt, the tail of which was half untucked. A bird’s nest of hair held at bay with a crocheted sweatband of brown and green. Hollows beneath his eyes and the stink of old pot about him.

He stood waiting, watching the narrow waterway ahead, a row of toothpick trees where white cranes perched to catch the rising sun. Behind him, a ragged line of sweetgum and pine, and beyond these: the great wreck of Sabbath House, laid bare in the dawn. Squares of cardboard in the still-broken western windows; shutters missing slats; peeling white porch columns strangled by saw briars. The roof a hodgepodge of tin nailed down over copper where the storm, ten years past, had torn half of it free. All manner of leaks inside, Avery knew. Cracking plaster and water stains and furring strips like ribs exposed. The weight of that house fell like a yoke across the dwarf’s shoulders. Shoulders that had borne far more burdens than nature had given them width or strength to bear.

And yet. Here he was.

At a quarter past seven, a small engine droned up the inlet that flowed off the Prosper River. Miranda Crabtree’s boat emerged out of the mist between a marshy strip of land and a stand of cedars. Tall and sinewy at the tiller, she wore a threadbare gray sweatshirt and dirt-pocked jeans rolled at the calves. The sleeves of the sweatshirt were torn off and her arms were hard and lean. Avery felt a familiar stirring at the sight of her, some feeling deep in his breast he’d never named for fear of speaking it aloud, either to the Crabtree girl in a moment of weakness, or in dreams, where he lay in bed beside his wife, who loved him far more than he deserved.

The boat’s engine cut out. Miranda tossed a rope and caught the lowest rung of a crudely nailed ladder at the end of the dock. Avery tied the rope off to a piling. She handed up the paper sack from the Igloo and waited. He counted the cash, produced a much thinner fold of bills from his own shirt pocket. This she did not count but stuffed into her hip pocket. She passed the empty Igloo up the ladder. “You look like hell,” she said.

“Handsome Charlie wants to talk,” Avery said and hooked a thumb over his shoulder.

She looked up the gravel lane from the dock, to where a white Plymouth cruiser was parked in the shade of a blood-red crepe myrtle, blue bubble light on the roof. A fat man in a hat filled the passenger’s seat, blob-like, a thin line of cigarette smoke curling through the cracked window.

“Why?”

Avery shrugged. “He doesn’t tell me anything.”

“Cook’s gone squirrelly.”

“Squirrelly how?”

She shrugged. “Squirrelly. Says tell you watch out for yourself. Says you’ll know what it means.”

Avery’s mouth tightened. “Well,” he said, after a moment. He cut his eyes to the Plymouth. “He wants to talk.”

Miranda looked from the Plymouth to the inlet, the river beyond. Avery watched the muscle in her jaw work.

Behind the dark glass of the Plymouth’s passenger window, the cherry of the fat man’s cigarette flared.

“He knows where to find me,” she finally said.

“He won’t like that.”

But Avery’s voice was lost in the cough of the motor and she was gone, quick as she had come, wake rolling back beneath the dock.

When she was out of sight, he walked the sack of money up to the Plymouth, dragging the empty Igloo over the gravel. The passenger’s window cranked low, revealing the immense dark shape of Constable Charlie Riddle, two chins and a black satin eye patch beneath a badged fedora, the brim extra-wide, neck fat beneath his shorn hairline like two rolls of quarters. Riddle took the sack from Avery and thumbed the bills, lips moving around his cigarette as he counted softly to himself.

Riddle’s deputy, Robert Alvin, sat behind the wheel, rail-thin and fanning at flies.

“She said—”

Riddle held up a hand, still counting. Satisfied, he opened the Plymouth’s glove box and shoved the sack in among paper napkins, a spare set of handcuffs, a citation pad. A single pair of white cotton panties dropped out like a bird fleeing a cage.

“She said if you want to see her, you know where to find her.”

Riddle tucked the garment back in, had to slam the box twice before the latch caught.

“Teia and I are leaving tomorrow,” Avery said. “First light. We’re taking Grace, we’re walking out. We’re done, Charlie.”

“Walking out,” Riddle laughed. “Just stick out your thumbs when you hit the highway and fly, eh? Where y’all headed?”

“Anywhere but here.”

“Well.” Riddle flicked ash out the window. “Just remember, John-boy, you can light out with nothing in your pockets or you can light out with pockets full. Which you rather?”

Avery thought of Grace. “How long?” he said.

“Another day, two tops.”

“Cook may have split on us. You can’t ferry dope if there’s no one to take delivery.”

“Who says they ain’t? Maybe I made me some new friends.”

“You never had a friend in your life, Charlie.”

Riddle smiled, shrugged. “Figger of speech.”

“You owe me three grand for the last six months. I know you’ve got it. You’ve been helping yourself to my share ever run. Last two, I got nothing at all. I have to pay the Crabtree girl, I have to gas up the generators to keep the grow lights burning, I have to buy fucking epoxy to patch the pipes when the goddamn toilets won’t flush—”

“How much you say I owe?”

“Three thousand.”

“See, that’s funny, I thought it was two. Or was it one?”

Avery said nothing.

“Don’t be sore, John. Just make sure the last of that dope’s in jars and ready to go by tonight. Then you head on back over to yon shack and crawl in bed with that long-legged wife, right next to that pretty baby, and just drift on off to dreamland for a spell. I wrap this whole thing up, you’ll get everything you’re owed, you and the missus. I promise. And that’ll be the end of Billy and Lena Cotton’s grand experiment here on the Prosper, once and for all. How’s that sound?”

Avery looked to the heavy iron gates of the compound at the end of the lane. They stood open. Across the gravel county road, surrounded by chain-link, was the low, windowless brick building that had once been Holy Day Church. In back of the church, a red steel broadcast tower, at the pinnacle of which was a wooden cross lashed to the metal with rope. Nailed to the cross, in a grim parody of the crucifixion: the long-rotted corpse of a white whooping crane, its six-foot wingspan all bone save for a few last shreds of flesh and feather. Gourdlike skull and scissor bill turned up toward heaven, eyes empty hollows. Avery didn’t know who had put it there, or why, but he felt no particular horror at the sight of it anymore, only the weariness of time and failure. “It sounds too good to be true,” he said.

The fat constable smiled, flicked his cigarette past the dwarf into the lane. “Get some shut-eye,” he said. He tipped his hat, cranked up his window.

Avery stepped back as the car rumbled away.

Sabbath House cast its horned shadow over an unkempt lawn thick with yellow-blooming dandelions as Avery made his way up the lane that bisected the property, dragging the Igloo behind him. Past the paint-flecked shotgun houses on his right, bare gray board showing through like exposed bone, the porches of three fallen away with rot. All dank and empty now, save the one nearest the gates, where Avery’s wife and infant daughter slept on through the morning heat. Here, the porch was swept clean and the two-seater swing that hung from eyebolts in the haint-blue ceiling was free of widow webs and wasp nests.

The greenhouse—his greenhouse, John Avery’s and no one else’s—stood on an open patch of ground across the lane, about fifty yards east of Sabbath House. It was iron-framed, Victorian, like so much else on the vast, wooded property: a resurrected ruin. Who had built it, some rich plantation wife? Possessed of an urge to grow something that was hers and hers alone? It had stirred him, this wreck, when he’d first laid eyes on it at nineteen, himself a new addition to the Cottons’ upstart ministry. The brick foundation crumbling, panes missing in the gables. These, Avery had covered with blue plastic. The glass he had blacked out with aerosol paint, every inch of it. Purpose conjured from neglect. A forgotten thing remade. The dwarf’s own story told in glass and paint and steel and the careful cultivation of new life.

He pulled a cinder block out of the weeds, stood on it, and unlocked the padlocked door with a single key that he wore around his neck on a length of knotted rawhide.

Inside, the plants grew three and four abreast in old tractor tires and wooden boxes and plastic five-gallon buckets. Those nearest the front were low and dense and pruned, while those at the back stretched six, seven feet high. Fluorescent lights hung on chains above them, backed by tin pie plates that made them look like flying saucers. He could hear the sound of the generator out back, chugging away, the lights above always burning. Avery shoved the empty Igloo against the wall and climbed onto a step stool and stood at a workbench scattered with cured buds and stray papers. He took up a bud and mashed it between his fingers and rolled it, tacking and licking the paper.

We were a whole community of fools, he thought. Me, not the least among them.

He sat on the gravel floor of the greenhouse, beneath the tallest trees, and smoked.

Later, weary, thickheaded and high, the sun climbing behind the trees, he crossed the lane to the last shotgun house. He tromped up the porch steps and went in through a ragged screen door, into the living room, where there was a couch with a busted spring and a ratty wingback chair, beside it an end table and an orange glass lamp with a dented shade. Through the kitchen, where the empty icebox stood open, a vaguely sour smell emanating from inside, palmetto bugs fleeing over peeling linoleum before him, and into the bedroom, which was small and cramped, a mattress sagging in an iron frame. Knotholes in the walls through which daylight peered. He climbed into bed beside Teia and lay atop the covers in his clothes. The baby lay beneath the single sheet, molded to the curve of her mother’s belly, mother and daughter both naked in the humid morn. In the window, a box fan blasted warm air. Teia lay between Avery and the baby, she a foot taller than his four-seven, her dark skin damp with sweat. “I love you,” she murmured, voice thick with waking.

“I love you,” he said.

Her eyes didn’t open. “What time is it?”

“Early. Go back to sleep.” He squeezed her hand.

Avery soon fell asleep and dreamed of a menacing figure in black, limping to and fro in a slanting room high above the ones he loved.

SIGNS AND WONDERS

FAR BEHIND SABBATH HOUSE, DEEPER IN THE BLUE pine woods than any congregant had ever been, on a slight rise at the center of a clearing, stood the burned-out shell of a forgotten stone chapel, its buttresses holding fast to the earth like the wings of a crippled dragon. Here, in a cold black crypt beneath the church, the old dying preacher Billy Cotton dreamed of a girl, darting among the woods, a child of twelve in a white dress soiled with river mud. A faerie creature. Cotton chased after her, and the trees grew thick and tangled and great rotten trunks surged up from the moist floor, roots and spiderwebs and shaggy leprous birches. A clearing at the base of a hill, where the child stopped, waiting. Holding out her hand. He took it. The moon shone on kudzu vine growing up the rise. A dark old shack at the summit. From beneath a stilted porch, carried by the wind, the oily reek of fish.

“Your hour’s near,” the girl said, her fingers twined in Cotton’s, so soft, so warm.

He came awake.