Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

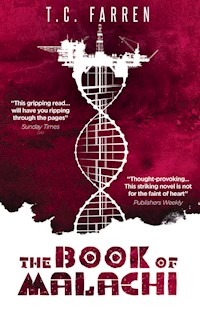

In this frightening, high-concept science fiction thriller, a mute man must confront the horrors of organ farming on a deep-sea oilrig.Longlisted for the Sunday Times Fiction Prize SANominated for the 2020 Nommo Awards for Speculative Fiction by Africans"Will have you ripping through the pages. Part thriller, part horror, part speculative fiction: this gripping read goes to the heart of ethical quandaries, forcing the reader to ask: "What if it were me?"- Sunday Times (SA)Malachi, a mute thirty-year-old man, has just received an extraordinary job offer. In exchange for six months as a warden on a top-secret organ-farming project, Raizier Pharmaceuticals will graft Malachi a new tongue.So Malachi finds himself on an oilrig among warlords and mass murderers. But are the prisoner-donors as evil as Raizier says? Do they deserve their fate?As doubt starts to grow, the stories of the desperate will not be silenced – not even his own. Covertly Malachi comes to know them, even the ones he fears, and he must make a choice – if he wants to save one, he must save them all. And risk everything, including himself."Sharp and compact but devastatingly poetic. This book packs real power into every page."- Charlie Human"Farren has created an extraordinary narrator in Malachi... [An] intense and memorable [read]."- SFX

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Acknowledgements

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Book of Malachi

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095197

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095203

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: October 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 T.C. Farren. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For David

MONDAY

My job is to check the plastic, see that it seals off the body parts, splays the flesh flat like faces against a windscreen. The vulnerability of a chicken is in the angle of their wings. If you pull them, the skin stretches, eases back. A newborn’s legs have the same elastic, I have seen this at the refugee centre in Zeerust. Their skinny legs stay up against their stomachs, the skin on their thighs rumpled and loose. Now it is my job to see that the skin on the chicken’s limbs is stretched and tucked to hide the hack marks. The machine must seal their pimpled skin, hide the tatters.

I know what they say about me at New Nation. One of my assistants, Beauty, is eighteen. She chews gum while she tears the plastic off the corrections, a perfect black grape, her chewing gum the pip.

‘My granny’s getting old, she asks me the same questions, she forgets. “How was your day, Nono?” Later, “How was your day?” I told her about you, Malachi. I said not a sound comes from your mouth.’ Beauty smiles, her chewing gum stopped between her teeth. ‘Do you know how we say we will keep a secret? We say, “Don’t worry. I will make like Malachi.”’

The phrase echoes in my head.

I am a successful mute. Malachi, well done.

* * *

My boss and I meet on the packing-office steps. We almost kiss, we both fall back.

‘A woman was on the phone checking your psychometrics. A labour agent from Raizier Pharmaceuticals.’ Lizet’s face stays in the shadow, the sun colours her long neck yellow. ‘I said you’re always on time. You’re . . . appropriate. I said you understand instructions. Nothing wrong with his brain, I said. But, you know, he doesn’t communicate.’ Her mouth wilts. ‘The woman seemed pleased!’ Lizet steps outside. ‘Did you apply for something?’

I shake my head.

She checks my eyes for truth. Sighs, satisfied with the confusion she finds.

‘About two hundred corrections. It’s going to be a helluva day.’

* * *

All day I stroke the plastic back onto its track. I anticipate trouble, see it coming. My job is menial, but it doesn’t show. The plastic leaves no calluses. It erases my fingerprints, smoothes my hand into a black silk glove.

I rinse off the static in my basin. Above it, the mirror has the skin disease mirrors get in gloomy rooms, dark spots that spread. In it, my hair is soft and knotted. My eyes are shallow sand at the edge of the Tantwa River. I have a cat’s head, wide across the eyes, tapering to the chin. The mirror is so high, I can only see the slight lift of my top lip. I cannot see my teeth, miraculously unblasted, unchipped by molten blade or machine-gun butt. I cannot see my fine scar, smoothed by a volunteer plastic surgeon.

* * *

I rest on the bed I bought from a man who went to jail for stealing chickens. The mattress has two dents, hollowed for a man and a wife, a virgin ridge in the middle.

I can say that word now. Before, it would have meant a bolt through my body that ripped off my fingertips.

Virgin. Virgin. I would say, over and over in my mind as I pressed the wires to my testicles.

Virgin ridge.

* * *

Every twenty-four hours, I slip into the dent on the right. I take only the space I need, the air that I must breathe. At night, when the air is abundant, I run on the spot. I travel ten kilometres in the same place. In the morning, I go to the toilet in my shorts, drip two drops on the seat. Clean it. For breakfast I cook Jungle Oats in a small pan with no handle. I eat it with Huletts sugar and real butter. I am rich enough to buy butter.

I inhabit number twenty-nine in the long line of the men’s hostel. They are stables, really, with a flush toilet in the corner. We peer over the top of the doors like dark horses at the scrappy grass. Beyond is a road pitted from rumbling trucks, bullies arriving with military frequency, carrying not men with weapons but live chickens with broken legs from being shoved into crates piled six storeys high. Now and then, a truck filled only with heads. I turn away.

I have seen decapitation. The head disengages as if the spine is nothing. A mere rumour.

TUESDAY

The Raizier agent lets my hand go, shocked by its silkiness.

‘Susan Bellavista.’

Her cheeks are florid, her accent American. Her eyes are cornflower blue, pale petals crushed by hooves or running feet. The only signs of danger are her thick, languid fingers and her shoes, pressed together under the desk. They are polished and stiff, the grey of gunmetal. The leather climbs all the way up to the ankle bone.

‘Malachi Dakwaa. I have a job for you.’ The agent reaches for her tall, curved bag, red leather with a black handle. She splits it open like a carcass. Pulls out Africa, unfolds the map. Sixteen plastic squares knock staccato on the wood. She points at my country, coloured in pink.

‘Which province are you from?’

I touch the province next to mine.

‘Which village?’ she asks.

A door shuts in my throat.

‘Malachi, who did this to you?’

I see flying splinters, shattered school desks.

She tries a gentler way. ‘Malachi, let me just say, what they did to you and your people . . .’

I push back the people clamouring, steal air through their limbs.

‘You can correct it. Those monsters who kill with machine guns . . .’ She checks to see if she has hit broken skin. Her words drift out of focus, refuse to hold on to the tail of the one in front. The agent’s cinnamon breath disguises her predation.

‘What we do on our medical programme is get these murderers to save lives.’

I blink, try to make her out against the sky.

‘They can’t harm you.’ She watches me for signs of fear. ‘No danger.’ When she smiles, I see her eyeteeth are slightly grey. ‘Malachi. Today is the luckiest day of your whole life.’ Her fingers creep across the desk, her soft arms stick to the top. She wants to touch me.

‘Do you want a tongue?’

My head snaps back, startled.

She nods. ‘Raizier needs a new Maintenance Officer. As payment, they will graft a tongue for you.’ She sews hasty stitches before her lips. ‘I’m talking about the best surgeons alive.’ She doesn’t trust my English. ‘The best medicine.’

A force surges up my throat, completes my stump. A phantom tongue. She sees it boasting there like an erection. She sees the cataclysm in my eyes.

I did not know I wanted it.

My foolish eyes bathe themselves in salt. I cry before this large peach skirt and her two stiff shoes.

God has decided I have been punished enough.

‘Go home and think about it,’ says Susan Bellavista.

* * *

I am a hungry animal, leading with my head as I gallop to the sound of my bullish breath. I will have a living, breathing tongue that can curl and lash and spit. A tongue that can tap the palate behind my teeth, suck air off my molars, make my Kapwa clicks. I am a broad-faced bull with a wet chest. I am Taurus in the Times.

* * *

My boss gives me the Times every week.

‘Take it for your fires,’ Lizet says.

Each of us has a drum outside our room, but I don’t light fires, in case people come. I bring my lunch in the Times, vetkoek and jam, no evidence of it being read.

If people knew I could read, they would ask me about my father, my mother, my lover. They would say to me, ‘Malachi, write a reply.’

* * *

Lizet is hunched forward like a chicken now, her shoulders flared to flap over her desk. ‘Why-y-y?’

I turn up my hands, but there is nothing to read.

She throws her digital pen on the release form on her desk. It bounces and hits the blades of her solar fan. She doesn’t laugh. ‘No explanation.’

The stump of my tongue sinks into the floor of my mouth. I’m going to be reconstructed, I want to say. Remade.

Lizet waves a trembling hand with faint purple patches. ‘You’ll lose a month’s pay. Why don’t you wait?’

I let my head swing from side to side.

‘Malachi. You’re strange.’

A conviction, for slipping from her life like a loose page.

But she won’t feel any difference in the weight. She will train someone new in two afternoons, someone who can smile and sing, perhaps talk of their love life.

I want to pick Lizet up, feel her pointed purple knees poking my thighs. I want to squeeze her hard, implanted breasts against me and say, Lizet, I will come back one day. Then I will laugh and say, Sorry for leaving you so suddenly.

For seven years I have been her best quality controller, excellent with the automated plastic packing machine.

* * *

Only once did I have to electrocute myself for my boss. That day, she wore maroon high heels of soft leather with thin, crossed straps. It was not the shadow of her buttocks beneath her dress. I did not lust for the diamond that forms below a woman’s bum. The problem was, my boss had perfect ankles.

* * *

Lizet will miss talking without causing offence.

‘It’s because you don’t speak, Malachi. That’s why you have such good eyes.’

She will miss my patronising shrug. Whatever, Lizet.

She took my silence as affection, which is strange when you think that I never, not once, made a single sound. Not even when the locals slapped me at the Nelspruit taxi rank.

‘What’s this? Makwerekwere.’ An open-handed punch. ‘What country are you from? Darkie!’

I showed my empty eyes, my open palms. For this I got a dislocated jaw, like a badly hung door.

WEDNESDAY

Today the agent’s hair lifts up like a wig. She wears a loose woman’s suit of baby blue. I check her feet under the desk. Her shoes are navy blue. On each ankle is a dark mark from pressing them together. Her hair follicles are black from constant chopping.

‘You will be working offshore. On the sea?’

I nod.

‘On a rig. It’s like a boat, but it has . . . legs.’

I smile inwardly.

‘Malachi.’ A thread of cold threat coils in Susan Bellavista’s voice. ‘Confidentiality is the most important thing about this job. The consequences are very, very steep.’ She taps the document with a clean nail. I give the plastic sheet a blank stare, but I read discreetly.

The organ is awarded on a leasehold basis. If the signee speaks of what he/she has witnessed, Raizier has the right to retrieve the organ without legal recourse.

‘What this means, Malachi, is that if you ever talk about what you have seen, we will claim back your payment.’ She waits. ‘Do you understand me?’

I swallow some stinging spit.

‘This is top-secret science,’ Susan growls. She whips a digital pen from somewhere. ‘Can you write your name?’

I hesitate.

‘Just a mark?’

I grip the pen like it’s a captured snake. I force its tip down near her fingernail, fight the reptile into a grim, deep M.

Susan lets go of her breath. There is a bitter triumph in the way she says, ‘Good.’

* * *

I stop at the factory shop, buy a new radio for the deep sea. It will be my secret hardware. If they search me, they will see a radio for entertainment, not a strike that rips me inside out, a Molotov cocktail for my genitals.

* * *

I usually roll my clothes up tight like intestines but today I lay them flat in my suitcase, each pair of trousers, each shirt unfurled. I run my extra belt along the edge. My duvet, I roll up and tie tight. I bought it from Kashmir’s with my first New Nation salary. It has feathers inside, the dead chickens’ gift to me, perhaps for letting them spread their limbs on a polystyrene tray; not live crushed towards their own fat hearts, their cage cranking smaller every six hours. This is how fast they grow, their own fat cells shoving into each other, bruising their inflating heart that can do no other than punch back, pump.

I throw in the cheap yellow Nokia Lizet gave me for after-hours callouts. I dare not take any books. In a sudden spasm of longing, I tuck an ancient roller-gel pen into the suitcase lid, and a thin white pad made from real paper. I’ll die without words, surely.

For fifteen years I have lied about my literacy, when the truth is I read any words that dare to float close. I read the plastic magazines dumped in the shallow bush – Shutter Speed Photography, Cat Lover’s Journal, S.A. Motorboat. I read advertising flyers that truly fly in the wind. I read warning signs on everything, disclaimers. Ask me the ingredients on the Colgate shampoo bottle. In the bus I read long-distance over shoulders, so people think my fixed stare is vacant, perhaps autistic.

Every three months I take my suitcase on wheels to the Hospice shop in Nelspruit. I pack in thirty-six books from the waste crates in the corner, three books to read per week. I rattle the case over my threshold, shut the door with a double bang. In my locked room, my boxer shorts on to cover my shame, I read with my electric wires standing by.

Where will I hide those bodies now?

* * *

I have no choice but to light my first fire. A man is snoring two doors down. There is a whispering beyond, the whimper of a child. Someone else is smuggling what they love. No visitors are allowed overnight. Here at New Nation, the men sometimes sleep in the bush on cardboard sheets in order to cradle their children or make love to their wives. Tonight, the child in number eleven has two scared parents and two milky breasts. I know this from the uncertainty of his cry. His parents are risking their monthly income to touch the baby’s face in the candlelight, play at being family in the hours between midnight and three a.m. when the chickens first feed.

I quietly pile some clods of chicken droppings into my fireplace. The chicken-shit flames crash silently towards the stars, envious of their silver. I drop the books in threes. They shrink and leave a fragile shell of black. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Margaret Atwood, E.M. Forster. Louise Erdrich, Charles Dickens, Kweku Adobol. Even A Short History of Everything. I let it burn alone. Whoof. It conspires towards silence, as if the pattern of civilisation and the jealous, obsessive energy of science were all only worth an exhalation. I am not joking. It was a definite sigh. The child cries in number eleven as if the flames are flicking his tiny feet. It is a swollen breast that muffles the child’s shout. I hear it in the fullness of the silence. Some things I know because I am not living. I am listening.

It is three a.m. A late, late cremation.

THURSDAY

I wheel my case into and out of the ulcers on the road. When I look back there are men’s eyes shining from every dark doorway. I breathe in, swing my case onto my head; keep a rough grip so I don’t look too womanly. It throws a shadow over my eyes, brings a Bhajoan sun to my thighs – a sun which was, a moment ago, South African. I forget my audience, drop my hands from my suitcase. I wipe the strange tears from my eyes.

What are these? Why now?

* * *

The agent is waiting against a bullet-shaped BMW that looks like a huge, shining suppository. Susan’s buttocks have warmed against the metal and spread.

‘Ahhh!’ her hips thrust off the car.

Relief ignites her eyes, illuminates the fluff on her orange trouser suit. Her suitcase is safely stored on the back seat, Scottish tartan. Next to it is a copper urn with a red ribbon tied around it. Susan clips open the boot. I don’t dust off my suitcase before I lift it: I have so much to apologise for, it’s better not to start. I’d have to apologise for the sweat I’m about to bring into her high-speed electric vehicle. And the fact that I won’t make a single sound for seven hours.

Susan shuts the boot. ‘Righty oh!’

I jerk my mouth into an awkward curve. That’s me, for seven hours. I get in with my sweat.

Susan’s brown suede boots take up the pedals like little leather men. We swing past the live man on stilts advertising Eddie’s Gas.

‘Here we go. Lesotho. The arse end of the world.’ Susan glances sideways at me.

I save my laugh. One day, when I have my tongue, I will laugh out loud about driving through the arse end in a bulletproof suppository.

Susan tears open a Bar One and takes two huge bites, like it’s a burger. She offers a chocolate to me, opens another one without apology.

‘My next assignment is in China.’ She taps the screen of her car media system. A man speaks gently, entreating us to speak Mandarin. Susan asks, ‘Did you learn Mandarin at school?’

I press the air with my fingers and thumb.

‘You’re lucky. In those days they didn’t bother with it in the US.’

I don’t know about lucky, I’d like to say. In elementary school, they taught us the words you might need at a conveyor belt. Lift. Twist. Alternative item. Red light. Green. Later, our Mandarin teacher, Mr Li, began to groom the chosen few. We learned to say, ‘Tell section seven to accelerate.’ Or, ‘You no longer have a job.’

* * *

After two hours in Susan’s car, I could smoothly recite corporate management Mandarin. How will we benefit from this arrangement? What guarantee can you give us? Do you have a digital privacy armour package? I have seen the sights, thank you.

Susan leaves a fingernail space between the front of her vehicle and the bumpers before us.

‘What’s this?’ she mutters. ‘A Sunday drive?’

A slight shift causes a hard drift of the car to the right, a hurtle towards an oncoming car. A mere twitch slaps us back in front of three flatbed trucks, just missing a string of car comets.

Once, Susan glances at my cheek and starts to ask, ‘That scar, was it from . . .?’

She ramps a blind rise, freefalls into a double-lane speed belt. Her question is a passing curiosity, dust from the recent past, part of the unremembered distance streaming behind us.

* * *

Susan doesn’t look at the view, even when we get near Egoli with its repopulated mine dumps, their terraces glinting black, their fountains so high you can see the water evaporating. ‘Shit heaps’ they call them, the workers like me. The shit heaps glimmer with rim-flow pools. I learned the term in the surplus Good Living magazines that came to the refugee camp still in their wrapping. We flicked through pictures of solar-charged chandeliers, garden statues of Mr Mandela in his suit among the ‘poor man’s orchids’ of the rich. There were wall-length sofas with floor connections for massage and warmth, photographed with huge house-cats fed on chicken intestines. Positively Feline, said the heading. One sofa had a young, live lion arranged across the back rest. Its golden eyes looked drugged, its body well fleshed like the lions Templeton Industries bred for the trophy hunters to prey on. The rogue lions, on the other hand, were skinny and wild, refusing a clumsy death at the hands of the panting, flaccid men who came all the way from America on jet planes to kill cats bigger than the ones that kneaded their pillows and meowed for tinned chicken.

No.

I shut my eyes. Why Bhajo? Why now?

* * *

Three hours from the city, the BMW slides past slow white figures on a golf course. A small white ball climbs the sky. A pale airport runway unrolls past the pressed green fields. Susan stops before a tall, gaunt guard. He meets my eyes once, sneaks a hostile shot. I know what it means. It means, Refugee.

‘How are things, Matla?’ Susan asks him.

‘Problems with kids on motorbikes. Racing.’

‘Brats,’ Susan says.

The guard flicks the boom up like it’s a toothpick. In the distance, three white helicrafts dip their noses at a white building.

* * *

Susan fetches her copper urn from the back seat, clamps a hand into my shoulder muscle.

‘Don’t let me down.’

As if, now that I’ve endured her chocolate farts and listened to her labouring through corporate Mandarin, now that I’ve sweated before impact perhaps five hundred times, we are friends.

I get out, embarrassed for Susan.

A pale hand waves from the door of the nearest helicraft.

I follow Susan’s shoes, crushing loose pebbles like little sadomasochists; keep my eyes off the white beast looming before us. I was airlifted on a stretcher to a field hospital, they said, but I was deeply descending then, clawing towards death.

I am about to fly for the first conscious time in my life.

Susan climbs the five stairs. Dragonfly, 554 FP, it says on the underbelly.

‘Malachi. This is Mr Rawlins.’ Susan turns to the captain, ‘Malachi’s mute.’ She drops her voice, murmurs, ‘Not deaf and dumb.’

‘Ah, good,’ the pilot smiles like he is genuinely pleased for me.

He has sliding silver hair in a side parting, white chinos, a collared white shirt. His teeth glow white. He has a white film on his tongue too, perhaps from the coffee in his polystyrene cup. Susan gives Mr Rawlins the copper urn with the red ribbon, holds out her hand to me. ‘Godspeed.’

She pounds down the stairs, swings her broad rear towards her too-thin BMW.

I drop into a seat, buckle up before the pilot tells me to.

Mr Rawlins leans across, taps the window. ‘Watch out for golf balls.’

Is he joking? The pilot smells of tobacco smoke. The hairs in his nose are coated in nicotine. I need him to be perfect, but I am dismayed to see two small spots of sweat at his underarm seams. A second bad sign, apart from the fungus on his tongue. Mr Rawlins opens a tiny Perspex fridge filled with stumpy Coca Colas and nine pie packets with pictures of little pigs.

‘All yours,’ he says. ‘It’s a nine-hour flight. We cross a time zone, so we arrive the same day.’

One piggy pie for every hour of flying.

The pilot folds into his cockpit and lights up a cigarette. The alarm screams indignantly.

Is he crazy?

‘Don’t worry, the petrol tank is at the back.’

I cough loudly, twice. He touches a button. Some kind of vacuum sucks his smoke straight up. Mr Rawlins starts the engines and coasts gently out of the range of bad golfers and their hard, white balls abducted by the wind.

There is the sound of air escaping under terrible pressure. As we lift up, my body dives for the earth, yearning. The pilot takes off with a stream of smoke pulling from his head. Nine little pigs smile through the Perspex.

This must be what they call adventure.

As we rise I let my eyes drop through the glass, see the crowns of houses and upended skirts of trees. The Dragonfly erupts through the clouds with barely a sound, more like a hum, as if the thin vacuum that removes the man’s smoke is keeping this craft in the sky.

* * *

After two hours, I am part of the Dragonfly. The machine breathes its mechanical breath through the soles of my sneakers as it takes me up to rub shoulders with the sun, fly within earshot of heaven, get the first whisper in. My fear is gone. The Dragonfly is taking me gracefully to a miracle of science. I will soon become a Raizier quality product.

Joy is fecund, but it rots easily. A dusting of old yellow appears on the rims of the pilot’s white sleeves. Fluff forms, a gathering audience to our exhaustion. Several times I check my GPS on my timepiece but it says, Aircraft Tracker Block On. Mr Rawlins doesn’t bother to speak to me, as if his words would be wasted on a mute.

The earth turns to heaving, sucking blue, but I would not call it a colour. It is a state, a plane, almost astronomical. I have seen the sea three times at Ladebi beach but this sea is as wilful as a seizure, as crushing as the unconscious mind. I would not call it blue.

* * *

After five more hours, the Dragonfly starts to slide from the sky. From a distance, the oil rig is a greedy creature crouched over its prey, covering it for consumption or mating. Closer, it’s a piece of industry broken off, a floating block of factory, with cement beams and steel cylinders sinking into the water, rooting it, I can only hope, in the earth’s core. Towers of criss-cross struts climb towards the sky as if someone was trying to build scaffolding to heaven. On the highest deck, a tall, round tower glitters near a landing ring. At the edge of the deck, an orange torpedo tilts down at forty-five degrees. A hi-tech lifeboat, ready to freefall into the sea.

As we fly closer, the sea smashes at the rig’s metal legs, turns them into twigs to be snapped off with a careless slap before the water demolishes the rig, devours it without tasting. The Dragonfly descends.

I can swim. I can swim, I tell myself desperately.

The pilot does something astonishing. He works the controls with one hand and pulls his shirt over his head with the other. Mr Rawlins has unexpectedly big breasts. He covers them up with a perfectly pressed shirt, identical to the one in which he’s spent nine hours sloughing skin. He clips down his mirror, combs his silver hair so it shines like the rotor blades through the window. He starts to brush his teeth, switching hands on the levers. He spits foam into his cup, speaks into the stiff wire on his cheek.

‘Nadras tower, Dragonfly 554FP, seventy feet and descending. Landing estimated at thirty-five seconds.’

I grip my seat as the rig heaves to meet me. As the deep sea separates into green, grey, black, I see black fins like plastic, pricking curiously in the water beneath the rig.

Am I dreaming?

A pillow of wind tries to stop us from touching down. We find a second of surrender, dive the last ten metres.

We land more heavily than one would expect from a man with excellent hygiene and a silver side flick, a man who is too important to communicate with a mute.

* * *

A Chinese woman stands like a sculpture cut from pearly white rock. After hours of flying, all the pilot gets is a slight bow. Her eyes are so black the midday sun tints them magenta.

‘Malachi Dakwaa.’ She smiles out of custom rather than kindness. ‘I am Meirong. The logistics controller on this project.’ She is wearing a black dress, square at her neck. There are black radio devices clipped to her waist, which is impossibly slim. Nipped. Her shoes are low and black.

I brace against the faint rocking of the rig, keep my eyes off the pale, polished bump rising above her ankle strap. The hair on her head is simply black water. She nods. ‘Come with me.’

Her flesh is shinier, more solid than I have ever seen. She is made of the same stuff as the life-size Buddha I saw in a garden shop once, but this woman is not the offspring of a gurgling teacher of joy without cause. She is the marble tree under which the fat man sat.

A black man steps from a huge old lifeboat with a torn-off roof. I want to duck away from his AK97, but I’ve taught myself to plant my feet, breathe before security personnel. The man’s muscles are laid in thin, strong strips, I can tell by his easy flex on the slightly shifting surface. Metal jangles with each tread, as if his pockets are heavy with loose change. His eyes are as bleak as the surface of this rig.

Oh, God. His epaulettes.

My fists form into bone.

They bear the same sign as the ANIM. I suck air through my teeth, force my eyes to the devil-thorn insignia on his chest. Nadras Oil, it says. A barbed star with a right angle hooked to each tip. A drilling emblem with a clockwise momentum, not the insignia of the devil who took my tongue.

‘Malachi, this is Romano, our security officer.’

‘Hello.’ His voice is full-bodied, his only fat. ‘Please give me your timepiece.’

I snap it off my wrist. He slides off the back, presses out the microchip.

‘Turn around, please.’ He pats every centimetre of my clothing. He pulls on rubber gloves. ‘Open your legs.’

I refuse to move.

‘Mr Rawlins gets it, too,’ Meirong says.

The pilot sighs, presents himself for inspection. The machine-gun man slides his rubber hand into the pilot’s trousers.

Meirong tries a personal touch. ‘Romano’s here to earn a heart for his little girl.’ The man winces as if she has just sunk a thorn into his heart. I must remember – the logistics controller is manipulative.

I spread my legs. The tickle beneath my testicles sets off a knot of nerves, expecting electricity. I want to turn and hit him.

‘Come, Malachi,’ Meirong says. ‘We must work right away. The prisoners are waiting.’

The murderers.

My heart dips, but I follow obediently. The Buddha in the garden shop was too focused on the pliancy of his toes, the expansion of his self as he bound a million universes into one locust swarm of love. He didn’t feel the bony coldness of the tree.

Meirong marches past the tall, round tower towards a windowless steel edifice. She stops at a metal door halfway along the building. Lifts a key card from her breasts. Unlocks it.

* * *

It is not so comfortable, this factory ship. From the top I see narrow passages, sharp corners intended for servicemen, not polished pearls with supple skin. But Meirong pours herself down the steep stairs, suddenly a Chinese gymnast trained in sullen concentration, reserving her smiles for an outright win. I follow easily. I am a runner by night, luckily, my stomach is like steel. We are dropping down some kind of thoroughfare between the two wings of the rig, down narrow flights with skinny railings, our descent marked by bright, reliable rows of silver rivets punched against the sea. We move silently, two agile apes through the man-made trees.

Meirong pauses at a door to the right that says, Private. Keep out.

‘Strictly out of bounds for maintenance crew.’ Her eyes shoot black bolts. ‘That’s you.’ She launches down again, stops at a door in the left wing. She speaks without even catching her breath. ‘Here we are. Maintenance.’

The door emits a rusted screech. We walk along a corridor painted with thick yellow paint like congealed egg yolk. We pass some closed doors, then a room with benches and a table bolted to the metal floor. I glimpse two thin streams of sunlight filtering in near the roof, the only openings to the sky I have yet seen.

Further down the corridor, Meirong taps at a door. ‘Your living quarters.’

She walks straight past any chance of leisure, leads me deeper into the building until I hear a low hum that might be the pressure of the sea. The sound gets louder, begins to ring like a soft, suppressed joining of voices. Just before the door at the dead end of the long corridor, Meirong swings up a set of spiral stairs.

At the top, computer screens cover two walls. The third wall is a window into falling space, the glass as thick as the crocodile tanks at the Tantwa River. Far, far below the yellow ceiling is a craving and a pulse; I sense it with the hairs at the back of my neck. I look away, try to focus on the screens, but my eyes refuse to understand the images I see – fluorescent light flung onto metal mesh, a sheen of human skin. That is all. I am not ready yet.

A young black man sits at a desk bristling with keypads and switches. His dreadlocks swing as he spins in his chair, jumps up to meet us. He has thick, wild eyebrows and an untidy patch of hair on his chin. His one eye is light brown, the other holds a splinter of green. His genes must be uneven. He grins.

‘Ah, Malachi, how are you, man?’

I offer him a careful smile, lock my teeth behind my lips. ‘I’m Tamboaga.’ He glances at Meirong. ‘From Zim.’

‘Tamba’s here for a kidney.’

His face becomes sombre. ‘My brother’s very sick.’

I nod in sympathy. Only then does the movement in the computer frames draw me in.

I gasp inwardly, try to understand the high-res pixels.

They are naked, all of them. An array of bent necks with long, dishevelled hair. They are all colours. A deep cocoa, here the ebony of the equatorial regions, here clay, here pink. Beards sprout on the men. A glimpse of black bush between their legs, tired and thick. A penis lolling, a breast swung to the side. Humans in cages.

Meirong says, ‘Forty of them, sourced from prisons all around Africa. After three cycles, they go back to their justice systems. We grow the organs inside them for six weeks, give them two weeks to heal. We’ve done one harvest with this lot. We start again on Thursday.’

I trace the patterns on their skin from pressing on bare metal, the deeper, longer gashes with puncture marks where a needle has passed through and pulled tight. Stitches.

With horror I count the wounds on a huge black man. Two cuts per cycle. One to go in. One to come out. Will there be blood?

‘Tamba runs the wiring and piping from up here.’ Meirong points through the thick glass. ‘Do you see how it works?’

Massive chains run inside steel tracks in the ceiling. Two rows of metal hooks dangle near the roof. Abbatoir hooks, but bigger.

I step towards the window, let my eyes plunge downwards.

Two rows of cages on curved cradles, bolted to the floor. Beneath each row, a twisted umbilicus of wires and pipes emerges from the floor, threads through the u-shaped cradles, drops away again.

I see no blood from this glass station. Beyond the thick mesh, all I see is the hair on their heads. I see shoulders, elbows. Here and there I see toes.

There are only a few women, but they are barely living. They will not waken my strange, sick libido.

‘This is a very sophisticated system.’ Meirong spins slowly, takes on a computer glow. She speaks with sincere pride. ‘A Chinese engineer set it all up for us.’

Tamba rolls his eyes at me.

And me, Malachi? Naturally I am speechless.

* * *

At the bottom of the spiral stairs, the murmuring returns. I recognise the sound now: it is the muted pulse of a foreign crowd. At the refugee centre in Zeerust, the people sheltered beneath the hum, sipped their sugary orange drinks, unwrapped their bread with their fingertips as if it might take fright and fly.

It is only now I realise that the people on the screens were completely silent. The subjects were suffering in mime.

Meirong stops before the door at the dead end. Through the steel, the wind of their breathing scrapes at the fine hairs in my ears.

‘The last maintenance man was a failure.’ Fury strikes her marble eyes. ‘The recruitment agent fucked up. Listen carefully, Malachi. The first rule for you is no communication. If you communicate, you’re out. And that agent,’ contempt curls her top lip, ‘will be fired.’

Now I see why Susan Bellavista was so excited by my inability to speak.

Meirong raises a key card, turns a tiny light green.

* * *

The inmates go quiet. I hear some whispers, a long, melancholic laugh. We are standing near the left-hand corner of the hall. The two rows of cages run towards Tamba’s glass kiosk, high above, on the left.

Beyond the mesh I see skin and hair, shifting. Animal madness, broken, still slightly stinking from the mêlée. The huge hall mimics the pull and heave of the sea. The room is breathing. I hear the swish of natural electricity.

No. They are not real people. The cages are too cramped for them to even stand up. They have no t-shirts, no sun-tan lines, nothing to show they were once a banker, a bin collector, a mother, a physician. They have no bags, no phones, no buttons to brand them. Only nipples, sunken parts, the pathos of ribs. I glimpse soft vaginal lips, the sudden drop of a skinny buttock. A sad reminder of fat pouched on a man with loose stomach skin. Meirong shuts the door behind us.

‘We keep them naked to avoid the logistics of clothes. And it’s easier for hygiene.’

She walks a few steps, stops at a metal trolley. She picks up a long tool with twin blades, and next to it some kind of leather sheath reinforced with metal strips. A giant dog’s muzzle or falconer’s glove, with steel locks attached to it. Meirong digs a fingernail into the fabric beneath her breast, presses a switch on a device on her hip.

‘Tamba, when did you last douse for lice?’

‘It’s been a while,’ Tamba replies through her speaker. He presses a key. ‘Yeah. Five days.’

Meirong nods grimly at him.

Tamba touches a switch. There is the hiss of nozzles unclogging. A soft mist drifts down from the roof. The sudden stink of pesticide as forty bodies cower and clench, try to escape it. There are some gasps, some words for God. Meirong leads me towards the cages, which, raised on their cradles, stand from my thighs to half a metre above my head. She waves her silver blades.

‘It is your job to clip and clean their hands and feet. Also report signs of parasites, bleeding, things the cameras could miss.’

She points to a transparent tube leading into a cage at mouth level. ‘Don’t worry about nutrition. We record their intake.’ She stops. ‘Are you understanding all this?’

I nod twice to convince her.

‘It’s a twenty-four hour cycle. Their supplements speed up nail growth abnormally. And you won’t believe what they get up to if you miss a clipping. They pick their wounds incessantly.’

She stops at the top of the two-metre wide aisle. Only now do I let my eyes sink behind the criss-cross wires. I was wrong about my libido.

The knees of these women will be my failing, with their smooth triangular caps, skin stretching over bone as they sit with bent legs. In row two, a huge, ruined beauty sits with her knee dropped to the side so her private parts open like a dutiful flower. I look away so as not to be mistaken for a man with normal, lurid tastes. I swing my eyes from a white woman’s finely hung collar bone, the way it dips, almost invisible, a mere shadow in the skin before it sinks into the roundness of her shoulder joint. I dream of my new radio beneath my tube of toothpaste, my aqueous cream, my Vaseline.

Meirong sighs. ‘Masturbation is okay.’

I almost choke.

‘We give them hormones to slow down their sex drive, but we can’t go too far. Too much suppression slows cell growth. No penetration though, it’s dangerous. Get Tamba to stop them.’

Does she mean a shock? My ears amplify the breathing, the shatter of a cough to my right.

Meirong turns to the sound, speaks into her device. ‘Tamba, number one, what temp?’

‘Umm . . . normal,’ Tamba replies.

‘Tell Olivia to check vitamins.’

The man’s eyes tilt upwards, chestnut with golden flecks. His face is so gaunt his cheekbones are like steel pins placed under his skin. He has a long penis. It lies lethargic, untrimmed against the mesh. There is a single burn mark on the inside of the man’s ankle.

Meirong points to the floor of the cage next to his. ‘Those are the waste plates. They look like nothing, but they’re very sensitive tools for measuring blood pressure, temperature, heart rate.’

An old woman sits with a full bum on the metal square, her legs, I am sorry to say, splayed. Her hair twists over her shoulder and drapes her groin in a long grey rope.

‘The subjects slide them to the side and excrete into a tray.’ Meirong’s face assembles into sweet, pretty smugness. ‘The waste is diluted with sea water and flushed away.’

I am relieved to see tiny numbers at the base of each cage. Meirong unlocks a rectangular hatch near the floor of cage three.

‘Watch carefully, Malachi.’ She clips the leather brace to the edges of the opening. Two pretty hands slide through the gap into the falconer’s glove. Meirong pulls on the leather strap so it traps and separates the hands in one drag. The metal buckle bites the leather, squeezes the knuckles together. Meirong sinks her cutter beneath the nail of a little finger. ‘This one’s a husband killer.’

There is a snigger inside the cage. ‘Only one, Miss China. You make it sound like there were a whole lot.’ The woman has glossy black hair tangled in knots. Her skin is as white as the polystyrene trays we slapped the chickens onto. Her breasts are perfect, curiously tilting, their eyes innocent. She has a mouth like a fig, plush with a dip in the middle. Inside her mouth there is sweet wet flesh, seeds of salivary glands, soft pink papillae. I can’t see them, but I know. The fig never disappoints.

We had a fig tree outside our hut. We watched every fruit grow, picked it at the first sign of pigeons.

I force my attention back to Meirong, sending a curve of nail flying against the mesh. The woman’s arms and legs are notched with healed cuts, a peculiar scaling; a strange mutation of a mermaid. And she sits like a mermaid, her knees bent to the side, her feet tucked under her bum. The soles of her feet are pink from the pressure, her only colour besides her thick, fig lips and her nipples like a rabbit’s nose. If you touched them they would retract. The fig splits, shows a dream of pink.

‘In case you’re wondering how I did it, I used a knife.’

Meirong smacks the buckle on the leather strap, loosens it. ‘You’re wasting your time, Vicki. This one can’t speak.’

Vicki withdraws her hands. ‘Can’t or won’t?’

Meirong steps back, delivers her high, triumphant line. ‘Malachi has no tongue.’

Forty pairs of eyes slide down my jaw, find the place where my tongue should be rooted. I lift my chin, try to blur my eyes, but the black-haired woman starts a giggle that staggers and trots along the cage walls. Behind me, a mad guffaw blasts from a large man with curling black sideburns trying to creep into his mouth.

‘Ah, Malachi.’ The refrain starts with the rope-haired crone, who, up close, looks like Granny Elizabeth. She, too, looks like she could do with an alcoholic drink.

‘Malachi-i-i . . .’ More voices coalesce, broken by higher notes.

‘Walk.’ Meirong marches me between the cages like I am mounted on a trolley. She warns the prisoners, ‘If anyone spits, you’ll get ninety volts.’

A woman’s imploring nipples press against the mesh, her hands against the cage making plump squares of skin. ‘Malachi . . . Help me . . .’

They whisper, they wail with open palms. Men, most of them, their voices deep with a raw catch. Oh God, beseeching. Meirong turns at the end of the aisle, leads me back the way we came. She bangs on number forty, the last cage on our right.

‘Josiah has killed over three hundred people.’

It is the man with coarse hair curling towards his teeth. He smiles at me. ‘Malachi.’ He savours my name like it is tender meat.

I want to run away as fast as my legs will carry me but I turn my back on him, swallow my spit. I walk after Meirong, suddenly foolish in white, a ball boy at Wimbledon, my shirt too thin across my spine.

* * *

Meirong shuts the door, stares at me in the sudden, sucking quiet. ‘Will you remember?’

The flames across my face, the agony that sent me into weeks of bloodless sleep.

‘Will you remember, when they get like this?’

A cocktail of shame and rage in the guerrilla’s eyes. Blood flowing like a river in the Tantwa watercourse, bodies arrested in the air then landing, weeping on the yellow linoleum.

‘We deliberately left the sedative out of their morning feed.’ There is not a nuance of remorse in her voice. She bows without a hint of respect. ‘I think you’ve passed the test.’

She leads me up the spiral stairs to Tamba’s observation station.

* * *

I ignore the flickering portraits on the wall, force my mind to register the piping diagram on Tamba’s computer screen.

‘We unclip the feed pipe when we winch the cages up,’ Meirong says. ‘As you can see, the irrigation is all done from above.’

Tamba notices my desperate composure. ‘Hey brother, you need a rest.’ He presses the switch on a printer, catches the sudden tongue of printed plastic.

‘Keep it.’ He hands me the picture.

But Meirong is not finished. She fixes on my useless mouth. ‘The two of you must work out a system of signals. The agent said you had first aid?’

I nod. A requirement for supervisors, but I learned more from watching doctors fighting to save flesh, not rubber mannequins.

‘Good. It’s too bad you don’t sign, but you’ll have to try. For instance, Tamba, how would he say, “Administer shock”?’

‘Umm . . .’ Tamba thinks. He presses his wrists together, mimes handcuffs.

‘Right. That’s punishment. Got it?’

I nod. Meirong watches my hand hanging uncooperatively against my thigh.

‘How would you say, “Check temp”?’

‘It’s okay.’ Tamba tries to spare me. ‘We’ll work on it later.’

Meirong slings a red lanyard around my neck, anoints me. ‘Your key card to the cultivation hall. Look after it.’ She flicks her liquid hair. A black wave breaks. She melts down the spiral.

* * *

It is a short passage and three unexpected stairs to the canteen. I stumble down them, suddenly weak. A woman gets up from a table with long benches fixed to it, all of it bolted to the minutely swaying rig. Her two big teeth make me believe her wide smile.

‘Hey, Malachi.’ She is thin and planed like a corner of a wall, with a prominent nose and protruding throat. In the deep, unpractised silence, she shrugs. ‘I’m here for my child.’

I glance at her arms, limp and hanging.

Meirong says, ‘Olivia’s baby boy needs lungs.’

‘They’re coming with this second cycle.’ Olivia exhales, her breath catching on the deadline. Her eyes are filmed with salt. She locks her fingers, twists her empty arms inside out. ‘I can’t wait.’

Meirong waves at a trolley piled with white crockery. ‘Come, let’s eat. Janeé is going to be late.’

The food is alien-seeming on this planet of sea. The carrots are a deathly grey, but I am not surprised. The memory of roots and plants and transpiration already seems incredible this far out to sea. My lamb chop looks like it was carved and cooked a year ago. My potato took the heat then crumpled into its plastic skin.

‘The food’s good tonight,’ Tamba says softly next to me. He laughs at my surprised twitch. ‘Yeah, brother . . .’

Across from me, Olivia shines the arm of her fork for nearly a whole minute. She is jittery about the days to harvest, shallow-panting to the date. I puncture my potato tentatively. This is my warning. She is falling to pieces after only thirteen weeks. I chew doggedly, tell my queasy body that the subtle shifting of the rig is a mere fantasy. Next to me Tamba checks the growth on my chin, assessing, perhaps, how thick my beard could be. He stares at my cling-wrap hands, sniffs discreetly for an odour off me, but I am sanitised by salt air and Solo deodorant. I don’t know what his story is, but Tamba is afraid of my black skin.

A woman sticks inside the door frame, forces her huge hips through the space. Her head is a plump pumpkin, her bum a plush double sofa on which two people could sit comfortably. She eyes me like she’s trying to guess if my species bites. ‘Malachi.’

I raise a hand to her, spoon some carrots in. As she sits, the joints of the bench surrender, then weakly fix.

‘Janeé used to cook for hundreds in the Craymar fish factory,’ Olivia says ingratiatingly.

Janeé’s face comes gently alive. ‘It was easy. After a few years, feeding a hundred people is the same as feeding ten.’ Janeé mulches her food like a waste-disposal machine, drains a glass of juice the colour of blood. The bench almost levitates as she gets up.

‘Thanks, Janeé,’ Olivia and Tamba sing as she crashes our plates onto the trolley and rattles it over the threshold. Her bum bulges and slides. I almost hear the pop as she arrives on the other side.

* * *

Tamba clangs with me down the passage, shoves on the door to my living quarters. ‘Here we go.’

It is a four-by-four yellow cell, painted lava thick. There are two beds against the walls.

‘You’re sharing with me.’ Tamba grins. ‘Sorry.’

My suitcase is already on one little bed, unzipped. Inside, everything is rumpled and rearranged. Tamba apologises on behalf of the bosses.

‘They’re serious about staying secret, dude. They trash our microchips. And their satellite shield is fifteen miles wide.’

They must have checked the lining of my case, my toothpaste, for what? I see it has been squeezed. I lift the jumble of my clothes. My radio is still there. The wires and the plastic plug. I think of the pretty bridge on the husband killer’s foot. I check the wall socket. Two-pronged. Good. I sigh. My very first sound since I arrived. I push my suitcase off the bed and lie down.

‘God, it’s like a gift Janeé’s got,’ Tamba laughs. ‘One thing’s for sure, they didn’t choose her for her cooking.’ I feel him prying at my shut eyelids. ‘She’s here to earn arteries for her son. They say it’s diabetes, but the truth is he’s a smack addict.’

My eyes sneak open.

Tamba smiles, teasing me with the mystery. ‘He doesn’t qualify for a transplant but the thing with a cook is, you need extra insurance. Think about it, Malachi, if the cook gets pissed off . . .’ He sprinkles air. ‘She can poison you.’

I stare at him without intelligence.

‘Do you wanna come and watch a movie?’

I shake my head.

Tamba backs out, dismayed by my meagre potential as a friend.

But I don’t rest easily.

The old woman in the cage brings me the scent of yeast from Granny Elizabeth’s palm beer. It brings me the shine of the crèche children’s skin, the sweat on their palms as they clutched on to my mother – with me, her little prince, always closest to her heart.

I roll over, face the wall, try to stifle the memories.

* * *

I fastened my lips to her nipple until I felt brave enough to wrestle and yelp with the children my age, while she helped feed the newborns with rubber teats.

The memories push up from the bottom of my spine, pass through the barbed wire around my heart. I roll into a ball, try to refuse them room at the inn. But they will not dissipate.

* * *

Cecilia worked night shift so she could be with me. She arrived home from the corn sheds and put me to her breast just as the sun was starting to sting her eyelids. There’s no point in having a child if you didn’t have time to love it, she said, and even then I knew she meant she would never leave me in a box to cry until my tears slowly dried in a factory crèche where I might as well be drip-fed. Where I would be lucky to get a turn to suck on hastily thrust rubber, thirty seconds to suck while my mother takes her slim place in the factory line, her elbows ticking, take, twist drop, hardly time to shift her weight to the other foot.

Sometimes my mother and Granny Amma would find a sliver of sun shining between the two crude fingers of the fibre-optic factory and speak of the politics of raising children who feel strong inside, not grow up to live on Granny Elizabeth’s palm-beer oblivion. Sometimes my mother fell asleep against the wall of the crèche. We clapped her with our small hands.

She opened her eyes. ‘Thank you! Ooh, it was the sun.’ She shook her finger at the sun. ‘Stop shutting my eyes!’

* * *

I press my face into my pillow, let my open eyes scratch against the pillowcase. I don’t want to feel my mother’s arms. The white pillow burns my eyeballs like the white, white sun on the corn fields of Krokosoe.