Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

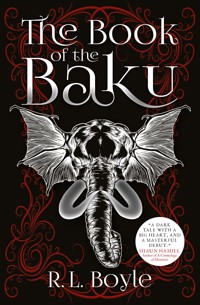

A Monster Calls meets The Shining in this haunting YA dark fantasy about a monster that breaks free from a story into the real world. Sean hasn't spoken a word since he was put into care. When he is sent to live with his grandad, a retired author and total stranger, Sean suddenly finds himself living an affluent life, nothing like the estate he grew up in, where gangs run the streets and violence is around every corner. Sean embraces a new world of drawing, sculpting and reading his grandad's stories. But his grandad has secrets in his past. As his grandad retreats to the shed, buried at the end of his treasured garden, The Baku emerges. The Baku is ancient, a creature that feeds on our fears, and it corrupts everything it touches. Plagued by nightmares, with darkness spreading through the house, Sean must confront his fears to free himself and his grandad from the grip of the Baku.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Now

Before

Day 1

Day 2

Before

Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

Before

Day 6

Day 7

Day 8

Day 9

Before

Day 10

Day 11

Day 12

Day 13

Before

Day 14

Before

Day 15

Day 16

Day 17

Day 18

Before

Day 19

Day 20

Day 21

Day 22

Day 23

After

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Also Available from Titan Books

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Book of the Baku

Paperback edition ISBN: 9781789096606

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096613

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: June 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

© R.L. Boyle 2021. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Owen

N O W

Some stories are true that never happened.

ELIE WIESEL

Sean runs through the garden, his only thought to put as much distance as he can between himself and his pursuer. Rain pours down the back of his neck, and his torch slices the blackness as he pumps his arms, a rapid seesawing blade of light. He fights a path through the bracken, heedless of the way it scratches and tears at his skin, gritting his teeth against the pain in his swollen knee.

He slams into the door of the shed as he hears an abrasive grating. Without looking, he knows the stone cherubs have turned to watch him. He tries to slide the key into the lock, but his hand is shaking too much.

Snatching a glance over his shoulder, he sees the figure coast towards him, not twenty paces away now. It glides as smoothly as if it were moving on runners. Though the rain-thrashed garden is otherwise clear of mist, the figure rides upon a thick bank of fog that obscures it from the waist down.

With a sob Sean turns back to the door and uses both hands to guide the key home. The lock clicks open and he is inside. He slams the door behind him, locks it, then grabs the chair and wedges it beneath the door handle, before backing away.

He strains to hear over the muffled thump of his own heartbeat, his ragged breath, the rain drumming on the corrugated roof of the shed, the wind whisking the trees. He is trapped. Trapped by the thing waiting for him on the other side of the door.

Knock.

Knock.

Knock.

Sean’s horror swells. He jumps back and bangs his hip against the edge of the desk, knocking the pages of Grandad’s manuscript to the floor. His legs crumble like dry sand. Huddled on the ground in a puddle of scattered papers, he points the muzzle of his gun at the door.

He is soaked in sweat.

Shuddering.

He shakes his head slowly from side to side. This can’t be happening. This can’t be real.

A sudden burst of static erupts from the old radio on the desk. It fades, as though tuned by an invisible hand, to the voice of a male broadcaster.

‘Has died in her 102nd year. Buckingham Palace said the end was peaceful, and the Queen was at her side. Members of the royal family—’

Sean’s eyes trace the length of the cord, which lies on the floor like a dead snake. Plug pins pointing upwards towards the ceiling. Drawing electricity only from the air’s malignant energy.

Knock.

Knock.

Knock.

Chills ripple over his skin. Breathing hard, he tightens his finger on the trigger, ignoring the sly whisper in his thoughts that says there is nothing he can do to protect himself.

‘“She was,” he said, “admired by all people, of all ages and backgrounds, revered within our borders and beyond.” Parliament is to be recalled for MPs to pay their tributes next week. The Queen Mother’s body will be—’

The broadcaster’s voice sounds old-fashioned, laced with the elegance of a bygone era.

Knock.

Knock.

Knock.

‘…who, at times, had seemed so indestructible, but whose life finally ebbed away at a quarter past three this afternoon. She died at her home close to the castle, where she’d been since the funeral of her younger daughter, Princess Margaret—’

The key pops out of the lock, lands with a dull thunk on the floor. Blowflies stream through the gap in the keyhole, the low drone of their beating wings accompanying the basal chord of Sean’s own horror. They darken every surface, an undulating mass that makes the room pulse like a living thing.

The door handle begins to turn.

Sean’s heart slams into his sternum. He wants to press his eyes closed and pretend he is somewhere else, somewhere bright and loud and warm, or just somewhere – anywhere – far away from here.

But he can’t look away.

Can’t move.

A tear tracks a path down his cheek, like the tip of an ice-cold finger. He stares at the door handle as it twists, knowing what stands on the other side, knowing what has come for him.

The Baku.

B E F O R E

For as long as he can remember, Sean has been curious about his grandad, but he never expected to actually meet him.

Mr Collins, one of Creswick Hall’s in-house psychotherapists, introduces them in a private room, then quickly makes himself scarce. Sean sits across from Grandad and studies his face over the two cups of tea that cool between them, seeking the family resemblance.

The old man doesn’t really look like Mum, but Sean catches glimmers of her in his expression, jigsaw pieces that match two faces. The shape of his eyes, the rounded nose, the dimple in his left cheek. Sean sees Mum’s face flickering beneath the surface of his skin, haunting him.

The old man’s face is weather-beaten, wrinkles crease the skin around his blue eyes. White hair explodes from his head, Albert Einstein on a bad hair day.. And he is tall – BFG tall – but with a curve to his shoulders that softens the severity of his otherwise imposing appearance. His grizzled eyebrows twitch and jerk with his every changing thought, like two fat caterpillars on steroids.

Sean likes his voice right away. Deep and low, it’s the sort of voice you just can’t imagine raised in anger, because it would pulverise your teeth and blow your socks clean off. The old man has charisma, even if he is about one hundred and seventy years old. A Gandalf-like twinkle animates his eyes, and he seems to fill the room with his presence.

Sean listens as Grandad tells him he has a house with a conservatory that will be perfect for his sketching, that he’s bought him a wooden carving set so he can learn to sculpt. He hopes he has the right materials, but if there’s anything he needs, all he has to do is let him know. He wasn’t sure what to get because he’d never been much of an artist. An author, yes, but that was many years ago now. He knows Sean doesn’t want to return to his old school so he has enrolled him at Allerton Mills, a local school with a great Ofsted report. He has even met with the headteacher, a lovely lady who knows all about his… circumstances. He has a library, too, did he mention that before?

He really does think Sean will get along just fine.

Everything is going to be alright.

Sean lets Grandad’s velvet voice wrap around him, tucking him up against all the world.

But he does not say a word.

D A Y 1

Grandad seems jittery when he comes to collect Sean from Creswick Hall, even though he has visited many times since their first meeting two months ago. He misplaces his car keys, only to discover after a great deal of searching that he’s left them in the car’s ignition all along, and he twice tells the story of how, that very morning, he found a pregnant hedgehog trapped in his garden fence. Sean feels a bolt of pity for the old man. It must be a shock at his age, taking on the care of a mute, partially-crippled thirteen-year-old boy. It would be strange if he wasn’t feeling nervous.

He slings his suitcase in the car boot. He hasn’t brought much with him: clothes, painkillers, his knee brace, acrylic paints and well-worn paintbrushes. The clay robin he sculpted for Mum. And the gun. He wants to get rid of it, but throwing it in the garbage doesn’t seem like the right thing to do and he definitely can’t leave it lying around. Its presence makes him feel nervous and grubby, but he tells himself if he keeps hold of it, at least it won’t fall into the wrong hands.

He gets into the car beside Grandad. His feet dangle over the edge of the seat like a little kid’s. He’s going to be fourteen in just a few weeks, but he wouldn’t look amiss in a class of ten-year-olds. It’s embarrassing. His left foot hangs a full three inches further from the floor than the right. He abhors his deformity. It is always the first thing people notice about him, their eyes dragging down his body, lingering on the twists of his legs, as though they are all there is of him.

When Mum had asked the doctors why Sean had been born with arthrogryposis, the condition that twists his legs into the shape of hockey stick ends, they were unable to answer. Random mutations are rare, but not impossible. Even with no genetic link, such things could occur.

In other words, it was just bad luck.

Sean has lost count of the number of surgeries he has undergone to straighten and lengthen his left leg. Now, his knee looks as though it has been through a mangler, and his legs are so severely scarred the thought of wearing shorts makes him break out in a nervous sweat. He called an end to the operations last year, resigning himself to an eternal limp and a measure of daily pain to save himself from the agony of further procedures. Mum had tried to persuade him to carry on, but not for long and not with any real fervour. She, better than anyone, knew he’d had enough.

In the car, Grandad fills the silence with nervous chatter, but Sean barely hears him. Words are white noise to him, broadcast on a frequency he has learned to filter out. His thumb circles the scar on the back of his hand as Grandad drives.

They pass the outskirts of Dulwood, the estate Sean grew up on, and the sight of it makes his chest ache. When they stop at the traffic lights, he sees Arlo’s little sister, Holly, skipping across the road in that funny way she has, every fourth step a shoe-scuffing shuffle. She’s carrying a paper bag from The Codfather and Sean realises it’s Fish-and-Chips Friday. Mel, Arlo’s mum, never needed to ask Sean what he wanted – a battered sausage with chips. For Arlo, it was XL haddock with mushy peas and an oven bottom cake. Holly, on the other hand, insisted upon studying the menu in the shop, taking her time to decide, as though she were sampling food from a Michelin-star restaurant. When Arlo and Sean teased her, she would shower them with insults, her brilliant mind spinning out quick-witted vitriol that would have made even the hardest lads on the estate cringe and hide their faces in their hoodies.

The traffic lights change.

Grandad drives on.

Sean twists in his seat to watch Holly, but she has turned down her street and he can’t see her anymore.

Less than fifteen minutes later, Grandad drives through the small village of Bockleside where he lives. It’s a much nicer neighbourhood than Dulwood. The houses don’t have bars across the windows for one thing, and instead of high-rise blocks of flats the properties are all detached, separated by fences and walls. Intercoms built into stone posts frame high iron gates. The roundabouts are planted with neat rows of flowers and there are splashes of colour everywhere. Sean thinks of Dulwood, where everything is grey and sad-looking and the only flowers people tended are the ones they’ve left by the lamppost outside Chubb’s Keys, where Spaceboy was run over and killed by joyriders.

The teenagers walking home from school in this neighbourhood wear blazers and polished smiles. Sean can’t see what they carry in their pockets, but he doubts they contain switch-blades or small bags of powder. He wonders if any of them are on first name terms with the local coppers, like he and his mates on Dulwood are.

They pass a large Tesco, and a park with huge wrought-iron gates. Sean’s thoughts turn – as they have turned many times over the past few months – to how close Grandad’s house is to his old estate. He wonders what happened between Mum and Grandad to make her cut him off the way she had. What could have been so terrible that she never visited him, never called?

If only Mum had stayed in touch with Grandad, things could’ve been so different. I could have been one of those lads, neat clothes, easy grin. What would Mum say if she could see me now? What did Grandad do to make her hate him so much?

Sean shakes the thought away.

Mum isn’t here.

Stupid to even think of her now.

Grandad takes a left turn onto a private driveway. Gravel crunches beneath the car wheels. The grass fringing the drive is overgrown, the flowers are wild. The road ends in front of an imposing house, a towering edifice of age-blackened stone. Automatic sprinklers water the grass, ivy snakes the walls.

Sean follows Grandad down a narrow path that cuts through a manicured lawn to the front door. His eyes move everywhere, taking everything in. The natural scruffiness of the driveway with its overgrown weeds and wild flowers contrasts with the neat grass and tidy flower beds around Grandad’s house. Sean wonders what this means, if it means anything at all. Perhaps the old man simply can’t be bothered to tend the entire driveway, or perhaps he is a loner, deliberately cutting himself off from the rest of the world, unconcerned with the things that lie too far beyond his own front door.

Grandad slides a key into the lock of the front door. Built from solid oak, punched with black studs and enforced with cast-iron hinges, it looks more like the entrance to a castle than an ordinary house. A wooden sign reading The Paddock is mounted above it.

* * *

Sean tries not to gawp, but he feels like he has stepped into a time machine and been spat out in the seventies. He is stood in a hallway that is easily as big as the front room in his old flat. The carpet is patterned in green Aztec, a blur of shades that feel as though they are shifting beneath his feet, and the wallpaper is an ugly mush of geometric browns and oranges. A wide staircase sweeps up to the second floor.

Grandad hangs his keys on a rack above a side table. There are other keys on the hooks, but only one of them catches Sean’s eye: a long, narrow key. The crenelated ridges of the age-blackened brass are like grimy teeth in a shattered grin. Looking at it makes Sean’s stomach clench.

Grandad is talking to him, but the old man’s words blur and dim under the thump of Sean’s pulse. The key grows sharper, almost psychedelic in its clarity, while everything else in the hallway fades. He has to force himself to wrench his eyes from it.

‘—haven’t decorated a room for you yet, thought you might prefer to choose one yourself,’ Grandad is saying. ‘That way you can do it up however you want to. Oh, and before I forget, Miraede will be popping over tomorrow. I think she just wants to see that you’ve settled in alright. Anyway, why don’t you look around and I’ll go make us a cuppa.’

Words of gratitude waltz through Sean’s thoughts in a perfectly ordered procession, but when he opens his mouth to frame them, they turn to wet cement in his throat. It is as though each unspoken sentence dries to create a thicker barrier for those behind it, and now his voice is blocked behind an impenetrable concrete wall.

The doctors and specialists explained his conversion disorder as ‘a way of displaying psychological distress in a physical manner to deal with a trauma’. The condition, they said, could manifest in different ways. Some sufferers lose their vision, some lose their hearing or their sense of smell, while others suffer paralysis.

Sean lost the ability to speak.

Grandad walks down the hall, leaving Sean alone in the hallway. The wall’s ugly colours swirl around him, making him feel as though he is stood in a funhouse corridor. He opens the nearest door and walks into a vast dining room. Dust sheets are thrown over some of the furniture and Sean imagines the shapes beneath coming alive at night, dancing through the house beneath their blankets. He quickly closes the door and moves down the hall to the next room, which is just as empty and unlived in as the last.

What am I doing here? If I’d passed the old man on the street a few months ago, I wouldn’t have looked at him twice. Maybe I did pass him on the street! It’s not as though he lives that far from Dulwood.

The tightness in his chest slackens a notch when he steps into a library. Smaller than the other rooms, it is made cosy by a log fire and two green and orange checked sofas. The walls are lined with books and an oriental rug covers the wooden floorboards. Traces of life provide a comfort Sean had not realised he had been seeking until he found it: half a cup of cold tea on the table; a rumpled blanket tossed over the sofa; logs in a wicker basket beside the fireplace; a messy pile of paperwork beside a computer. Sean catches a glimpse of a patio through slits in the blinds.

He moves to the bookcases. There are crime novels, gardening books, classics, memoirs. He starts pulling random titles down, examining their covers, sometimes reading the blurbs. Those that intrigue him, he keeps stacked in one hand. Sean notices a few of the books have Grandad’s name embossed on the front. Elbert Blake. He had forgotten Grandad used to be an author.

He trails a fingertip across the spines, tracing a line in the soft patina of dust. A sudden static shock makes him jump. He frowns, his eyes hesitating on the bookshelf. His fingertip tingles; the bones of his hand hum, like the tines of a struck tuning fork.

He pulls a book from the shelf.

It is a hardback entitled The Baku: A Selection of Short Stories. The front cover depicts a statue of a beast mounted on a plinth. The head of an elephant, merging at the neck with the body of a man. Its chin is dipped in a predatory pose and its wrinkled trunk, gnarled and scabrous, hangs between its nipples. Its elephant ears are latticed with capillaries, their thinning edges ripped and frayed. Curved yellow tusks protrude from its jaws, twin scythes stropped to a fine point. Its wide neck and shoulders are corded with thick veins that are engorged with dark blue blood. There is something insane inside the beast’s eyes, something terrible and timeless.

On the inside cover, there is a list of the short stories in the collection. Sean flips the book over and reads the back of the jacket.

When fears escape the burning pit,

And evils you did not commit,

Torment your dreams and steal your peace,

Your innocence screams for release.

The horrors grow, as horrors do,

Each night they boil and swell in you.

You dared not close your eyes to rest,

Or give yourself to sleep’s cruel test.

But sleepless nights will take their toll,

They whip your body, break your soul.

And in the end, despite your fight,

You tumble into endless night,

Where blood and tears clog your screams,

There’s no escape from your dark dreams.

Slaked in sweat you thrash and shake,

Give anything to finally wake.

No more of this! You’ve reached your end,

The time has come to tell a friend.

Confide in me, Child, and you’ll part

With that terror in your heart.

For there’s a darkness deep in me,

That feeds on pain and misery.

Give it to me, relinquish dread,

And fall asleep in peace instead.

Sean feels a delicious thrill of anticipation. He has always found a strange comfort in horror stories, though Mum never approved of his proclivity towards darkness.

There’s enough evil in the world, Sean. Why go looking for more of it in books?

Pushing thoughts of Mum from his mind, Sean walks out of the library, The Baku tucked into the inside pocket of his jacket, the rest of the books forgotten.

* * *

He stops on the staircase to study the photographs that line the wall. Even though Mum never used to talk about Grandad, she occasionally spoke about her own mother, Ocean Storm, who died of cancer when Mum was fourteen years old. Sean can tell from the slivers of Mum he sees in her face that the flame-haired woman in the pictures is her.

In one of the photographs a man stands behind Nanna Storm, his arms circling her waist. It takes a moment for Sean to realise the man is Grandad. His hair is dark, his face unlined, but it isn’t his youth that makes Sean feel as though he is looking at a stranger; it is the way he is watching Nanna Storm, smiling in a way Sean has not yet seen. Like there is happiness trapped inside his bones. Nanna Storm is looking into the camera, laughing as a breeze whips threads of fiery hair across her eyes.

In the next photograph, Nanna Storm is holding a chunky toddler. Even though the child bears little resemblance to the woman she will become, Sean knows it is Mum. There are other photographs, too, cataloguing Mum’s childhood: lying on a candy pink blanket as a baby, toothless and giggling at the camera; wearing a tulle tutu and a tiara, opening a present beneath a Christmas tree; in her school uniform, gap-toothed and grinning; posing for a professional photograph, Grandad looking slightly stiff, but Nanna Storm beaming unreservedly at the daughter wriggling in her arms. A perfect nuclear family, blissfully happy, unaware of what the future holds for them.

Sean swallows the knot in his throat and moves up the stairs.

The bedrooms are large and gloomy, possessed of the same neglected feeling as the empty rooms downstairs. Heavy brocade curtains are drawn across all the windows, thickening the darkness. Sean chooses a room at the back of the house with an en suite bathroom and a beautiful roll-top desk. There is a wardrobe in one corner, a set of drawers in the other. The bare, dusty light bulb throws out a bruised, sickly light, and even when Sean switches on the tassel lamp by the side of the bed, shadows dominate the room.

He tosses his suitcase onto the bed, opens it and takes out the box that contains his clay robin. He has covered it in bubble-wrap for safekeeping but now he carefully unwraps it and sets it on the window ledge. He takes the gun from his bag, puts it in the bottom drawer, then grabs handfuls of pants and socks from his suitcase and shoves them on top. The bullets, which he keeps in a plastic box, he tucks into the back of the wardrobe.

He leans over the desk and throws the curtains open. Dust swirls from the thick fabric, and when he squints into the sunlight he gasps in surprise.

Grandad’s back garden looks like a photograph taken straight out of Gardener’s World, but not one of those perfectly manicured ones where flowers grow in colour-coordinated squares. Grandad’s garden is wild and anarchic and alive.

Half the size of a football pitch, the vast lawn is edged by sloped borders of flower beds that rise and fall like the waves of a windswept ocean. Climbing roses the size of cabbages drape the boundary wall. Blocks of hardy winter vegetables grow in neat rows. A kidney-bean-shaped pond in the middle of the lawn is surrounded by stone slabs, and the huge tree beside it bursts with red berries. A nest swing hangs from one of its thick branches, and beneath its sun-dappled shade there are a table and four chairs. A white-framed greenhouse is nestled in the bushes, near a seating area decorated with potted flowers. Bird baths are dotted around, and as Sean watches, two robins swoop down to jab their beaks at the offerings there.

His gaze wanders to a dilapidated shed in the opposite corner of the garden, half buried beneath overgrown brambles and tree branches.

His breath catches in his throat.

Perhaps it is simply because the building is such an eyesore, but he feels the sudden urge to close his eyes or turn away. He resists, tethered by curiosity. Branches and vines have withered across the shed’s walls in a spindly embrace, lichen grows across the blackened windows, like rot over empty eye sockets. Five stone cherubs stand guard at the door, their lower bodies submerged in the tall grass. Their gentle faces smile beneficence, but Sean swears there is something shifty in their mildewing eyes. Something… not quite right.

The silence of the bedroom seems to thicken until it possesses a physical weight. Sean feels exposed. Watched. He spins round, sure there will be someone standing behind him. But, of course, there is no one there.

He takes a deep breath, expels it shakily. Telling himself he is being silly, he heads back downstairs.

* * *

‘Ah, there you are, lad,’ Grandad says, looking up when Sean enters the kitchen, which, with its Formica worktops and brown and cream floor lino, is as much of a homage to the seventies as the rest of the house. ‘Come with me, there’s something I want to show you.’

Grandad passes him a steaming cup of tea and leads him through the house, stopping in front of a locked door.

‘I know from your old art teacher how much you love to sketch and paint,’ he says, sliding a key into the lock. ‘So I’ve set up a sort of workshop for you. This is your room now.’

He opens the door and Sean follows him into a spacious conservatory. Sunlight cascades through the sloped glass ceiling, exposed red-brick walls are laced with veins of creeping plants, and a stone lion trickles water into a basin below. A patio door set in a wall of glass leads into the garden. Flowers decorate every shelf and ledge, they hang in baskets from the walls. It’s like Grandad scooped up a pocket full of summer before autumn could erode its colour.

Sean’s gaze rests on the workbench. A large oak table is laden with art supplies and equipment. There are paints of every variety: oils, acrylics, watercolours, pastels. An exquisite wooden watercolour box, a set of sketching pens, canvasses, brushes and bottles of brush cleaner. Sponges and rollers. A stack of art books. A wooden carving set. Sketchpads. Modelling tools. An easel. Sculpting clay and a roll of armature wire.

‘Your art teacher, Mr Donal—’

Mr Dolan.

‘—told me that you’d only just started working at sculpture but that you showed great promise. I thought you might want to experiment with it, so that’s why I got the clays and the armature wire.’

Sean knows from scrimping and saving for his own supplies that none of it has come cheap. The old man must have spent a fortune on him.

Sean moves to the table, picks up a book. Michelangelo: The Works of Il Divino. There are other books, too, about modern artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Francis Bacon, Salvador Dalí and Frida Kahlo.

‘To be honest, I didn’t really know what to get,’ Grandad says, his eyes moving over the equipment uncertainly. ‘Never been much of an artist myself, but the lady in the shop was very helpful. She said if there was anything you wanted to exchange then it wouldn’t be a problem. I’ve kept all the receipts, so…’

Sean feels Grandad watching him, hears the hesitancy behind his words, the deliberate delicacy of his tone. His kindness loosens something inside Sean. Words of thanks catch in his throat. Grandad nods once, as though he understands. He drops his hand on his grandson’s shoulder. The smallest gesture, packed with a world of unspoken words.

D A Y 2

When Sean comes downstairs in the morning, Grandad takes him outside to show him the hedgehog he rescued.

As they walk down the path, Sean can’t help but marvel at the garden’s beauty. Bursts of colour explode against the greenery, wind chimes harmonise with the chirruping birds, foliage rustles beneath a lick of wind. The space works a sort of magic on Sean, makes it easier, somehow, to breathe around the ache in his chest.

They pass the huge, red-berried tree, and Sean notices a gold placard nailed to the trunk: Ocean Storm 1955–2002.

As they approach the crate by the wall in which the hedgehog is housed, Grandad presses his finger to his lips – an irony that is not lost on Sean – then crouches down in the tall fronds of grass. Sean kneels beside him and peers into the crate.

The hedgehog is curled in the corner, half buried beneath a heap of leaves and straw. Grandad has attached a water bottle to the side of the crate and left a small pile of what looks like scrambled eggs on a little plate.

‘I think she’s pregnant.’ Grandad’s whisper smokes on the cold air. ‘Most hedgehogs have their hoglets in the summer months so they have time to bulk up for the winter. I’m afraid this litter will struggle to gain enough weight to survive hibernation. Still, there’s a chance one or two of them might survive.’

Sean can tell from Grandad’s tone that he does not believe they will. Perhaps he should feel bad for the unborn litter, sorry that the odds of surviving are stacked against them, but he doesn’t.

Being vulnerable doesn’t make them special; surviving is a struggle for everyone.

* * *

Sean is reading The Baku while eating his cereal when Grandad comes into the kitchen. The old man’s eyebrows jerk up at the sight of the book and the colour drains from his face. Sean looks at him in alarm, but Grandad just presses his lips together and turns away. He sets his cup in the sink then sits at the table with Sean to work through the crossword in the newspaper.

Sean returns to his book. The first short story in the collection is called ‘Luca’. Luca is a thirteen-year-old boy who struggles with insomnia and night terrors. For as long as he can remember, he has dreamt of the Mirror-Eyed Man, a tall, stooped and silent figure. Though Luca only ever sees the Mirror-Eyed Man’s silhouette in profile, somehow he knows that he must never look into his eyes, that to do so would be to erase sanity and give himself over to horror and madness.

As soon as Luca falls asleep, the Mirror-Eyed Man is there, sliding into his dreams as though he is always waiting on the edge of sleep, anticipating the direction the boy’s subconscious will take him. Sometimes, Luca dreams the Mirror-Eyed Man is sat on the edge of his bed or on the wing-backed chair in the hallway, sometimes he is stood in the corner of the kitchen or at the back of his classroom at school. But it is only when the old man lifts his head to look at Luca that the boy wakes up, sweat-soaked and screaming, moments from seeing what is reflected in that black-mirrored gaze.

Luca’s mother has consulted doctors, sleep specialists, therapists and hypnotists, but still his nightmares persist. Nothing seems to help, until the day he visits the carnival with his mum and baby sister and sees the Baku, an ivory-carved statue of an elephant-man, which claims to eat the nightmares of children.

Lost in the story, Sean is barely aware of Grandad’s presence, just as he is barely aware that his tea has grown cold and his cereal turned to gloopy mush. His spoon travels to the bowl less and less until even his breakfast is forgotten.

Luca stared at the Baku, clutching the sheet of paper upon which he had written his nightmare. Something about the statue made him hesitate to press the note into its mouth. He was reminded of the time he visited Madame Tussaud’s. He had been staggered by how real the wax models had looked, stunned by the precision of detail that had gone into the crafting of each one. And yet, as perfectly asthey had mirrored their living counterparts, he had not for a moment questioned whether they were alive. Their perfectly rendered eyes were empty, hollow in a way that betrayed the absence of soul.

The Baku is different. When Luca looks at it, he senses a dark sentience crackling within it. As he considers the statue, he cannot quite shake the conviction that it is considering him in return.

Yellowed by the passage of time, its ivory flesh is like ancient papyrus, wrinkled and coarse. Its thick trunk is accordioned, its small, black eyes sunk in shadow-swagged sockets. The cords in its muscles are like steel cables, scored by deep blue veins. Like a bust from classical antiquity, its arms are severed at the shoulder, but Luca can see enough of its muscled neck and broad chest to know if it did have a body, it would be that of a man.

A little girl shoves past him, startling him from his thoughts. She pushes her note into the statue’s mouth. Something flickers inside the Baku’s eyes and a chill rushes over Luca’s skin.

‘Luca, come on!’ his mum snaps, Betsy squirming in her arms. ‘We need to go, your sister’s getting cranky.’

Luca nods and forces himself to take a step towards the Baku. He knows he is being ridiculous, but the thought of touching the statue is repellent. He is suddenly convinced that as soon as he puts his scrap of paper in the Baku’s mouth, serrated fangs will clamp down on his flesh, severing his hand at the wrist.

But his mum is watching him, waiting. The dark pouches beneath her eyes remind him of last night, when she had rushed into his room and shaken him from sleep as he screamed and thrashedbeneath his covers. Luca knows that he – not his baby sister – is the reason she looks so exhausted. Betsy is a brilliant sleeper. A dote. At four weeks old she was already sleeping through. Luca, on the other hand, cannot recall the last time he had a decent night’s sleep. He is sick of hearing people tell him he will outgrow the nightmares with time. He wants to outgrow them now.

He lifts the scrap of paper to the Baku’s mouth. Apprehension surges through him, but he feels for a hole beneath the Baku’s lowered trunk in which to drop the note.

The walls of its mouth feel damp and soft. Warmth creeps over Luca’s skin and the sweet smell of rot engulfs him. He shudders, tries to drop the note, but the paper just sits there on the Baku’s tongue. Gritting his teeth together, he shoves the note further down the statue’s throat, trying to ignore the resistance he meets, telling himself he is imagining the pained look in the Baku’s eyes, imagining the choking sound emanating from the back of its throat, imagining the warm, cloying—

The sound of a ringing doorbell rips Sean from the story. Miraede. He had been so engrossed in his book he had forgotten she was visiting today.

Grandad goes to let her in, and Sean hears the murmur of conversation in the hallway, voices pitched low so he can’t hear what they are saying. A few minutes later Grandad comes back into the kitchen.

‘Miraede’s waiting for you in the library,’ he says. ‘You go on through, lad, and I’ll bring some drinks in soon.’

Miraede is sat by the window when Sean enters, and she smiles as he settles into the chair across from her.

‘Hi, Sean.’ He ignores her and looks out at the rain-streaked garden. ‘Your grandad’s house is lovely! I hope you’re settling in well.’

One thing Sean has noticed since losing his voice is how discomforting people find long silences to be. As though the quiet is a ditch, hiding a monster they are terrified to see, and their words are the rubble they have to keep shovelling to keep it buried.

Miraede is not one of those people.

When Sean does not say anything, she just smiles.

Like she knows what face the monster wears and is not afraid to see it.

‘Arlo has written you another letter.’

Miraede pulls an envelope from her bag and holds it out to Sean. When he doesn’t take it, she sets it on the table between them. Sean recognises the handwriting on the front, almost as familiar as his own.

‘He asked me to give it to you. Jake and Gracie have been asking after you, too.’

The scar on Sean’s hand itches and he rubs his thumb over it in slow circles. His gaze sweeps over the garden and settles on the shed. He shivers, despite the thick jumper he is wearing.

Miraede follows his gaze to the shed. When she looks back at him, her face seems a little paler, her dark eyes troubled.

‘Your friends miss you, Sean.’ Her voice is soft, like the rose petals Grandad so lovingly tends, and just as pretty. ‘You should write back to them, maybe invite them over here to visit. I’m sure your grandad wouldn’t mind.’

Sean’s thoughts spin back to when he lived on Dulwood. When everything was sweet. No, scrap that. Everything was crackerjack. He had a home, a real home, and he had friends. Brilliant friends. Life was normal, and though he did not know it at the time, normal was good. Normal was great.

‘Sean?’ Miraede is sitting forwards, her worried eyes on his face.

Admittedly, his old flat was a bit of a dump. The damp was so bad, the skirting boards were almost completely rotted away and the ceiling over his bed sagged with corroding plaster. The thin walls did little to keep out the cold, or stifle the sounds of the neighbours, who huddled, crablike, above and on either side of them. Conversations and arguments filtered through to Sean with no less clarity than they would through a cardboard box, and he regularly struggled to sleep through the maddening thump of someone’s bass or the rhythmic pounding of the horny couple upstairs.

‘Have you thought any more about the regression therapy I mentioned last time I saw you? It can be a useful way to help conditions such as yours. There was a patient I treated for conversion disorder not so long ago, a different presentation to yours, of course, but—’

Mum was only sixteen when she had Sean, and he wonders whether that was why they were so close. With little money to spare for the sorts of activities most kids could indulge in, Sean’s mum had been forced to think of things they could do together on a budget. They would go for long bike rides, play board games while stuffing their faces with junk food, visit the museum in town. When he was little, she would come up with art projects for them to do, helping him weave paper into colourful patterns or using food colouring mixed with glue to paint. As he got older, Sean began to come up with more ambitious ideas, and then it was he helping Mum when she got stuck. Making ships in bottles, DIY lava lamps or patio chandeliers.

When she found out that he had been selected for the Future Creators course, she had increased her shifts at The Dog and Gun, despite the fact she already worked too much. She had always hated Dulwood and promised him over and over that he wouldn’t live there forever.

‘—can’t protect yourself from pain this way, Sean,’ Miraede is saying. ‘You can’t just unplug the socket and disconnect yourself from the world.’

Sean feels a scowl cramp his face. He stares at the shed, thinking that, in many ways, it is just the same as he is now: shadow-draped, remote, silent.

And full of secrets.

* * *

As soon as Miraede leaves, Sean throws Arlo’s letter away unopened, then goes into the conservatory to finish reading the first short story in The Baku.

After feeding his note into the Baku’s mouth, Luca enjoys a few nights of dreamless sleep, but all too briefly. Paranoia begins to nibble at his thoughts. He becomes increasingly agitated, convinced someone is watching him. He starts to catch glimpses of the Baku and the Mirror-Eyed Man, sensing them always hovering at the peripheries of his vision.

After a few weeks of this, the nightmares return, only they are far worse than any he endured before. So vivid, so real, that even upon waking, Luca cannot be sure he is not still dreaming. The two worlds of sleep and consciousness, always so clearly divided, have merged into one, so that there is no relief to be found in either. He begins to find crumpled notes beneath his pillow, each one detailing, in a child’s immature handwriting, the dream from which he had just awoken. Luca knows, somehow, his note, his nightmare has roused the Baku. It no longer wants to sleep. It does not want his dream. It wants to purge.

Luca leaps from his bed, as though it has come alive beneath him. He spins round, crashing into his swivel chair, which rolls on its castors across the floor with an eerie squeak. His room smells ripe and foul, and even though he is laced in sweat his breath puffs in white clouds from his lips. He feels the Baku’s presence, like a slick film against his skin.

He lifts his pillow, already knowing what he will find there. Even so, the sight of the rolled-up wad of paper elicits a choked sob from his lips. Stifling his revulsion, he reaches down and picks it up, smooths it out.

Name: Luca RussellAge: 13Nightmare: The Mirror-Eyed Man

Luca stares at the note that he fed into the Baku’s mouth less than a week ago. The ink has smudged, the beast’s saliva making it bleed across the paper, but the handwriting is unmistakably his own.

The Baku has given him his nightmare back.

A flicker of movement at the edge of Luca’s vision makes his blood run cold. He is not alone.

The Mirror-Eyed Man is perched on the edge of his bed.