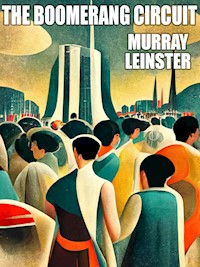

0,85 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Nobody paid any attention to matter-transmitters ordinarily. They had been in use for ten thousand years. All the commerce of the First Galaxy now moved through them. But what happens a planet's matter transmitter to goes awry—in an age when spaceships are obsolete?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 93

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION, by John Betancourt

THE BOOMERANG CIRCUIT, by Murray Leinster

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2022 by Wildside Press LLC.

Originally published in Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1947.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

INTRODUCTION, by John Betancourt

William F. Jenkins (1896–1975)—who wrote science fiction under several names, but primarily “Murray Leinster”—was one of the few early writers of speculative fiction to publish strong, relevant fiction over the course of 7 decades (Jack Williamson was another). Jenkins began publishing science fiction for pulp magazines before the term “science fiction” was even coined.

His success may have been due to his work in multiple genres. I have assembled his novels and stories into a series of collections for Wildside Press’s MEGAPACK® anthology line, and in researching his work, I discovered that he wrote pretty much everything imaginable, from romance to mystery to westerns, as well as science fiction and fantasy. Indeed, his published works number well into in the thousands—Wikipedia has an estimate of at least 1500—and I can easily believe it.

His first science fiction story, “The Runaway Skyscraper,” appeared in the February 22, 1919 issue of one of the leading general-fiction magazines, Argosy, and was reprinted in the June 1926 issue of Hugo Gernsback’s first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. In the 1930s, he published science fiction stories and serials in Amazing and Astounding Stories (the first issue of Astounding included his story “Tanks”). He continued to appear frequently in other genre pulps such as Detective Fiction Weekly and Smashing Western, as well as Collier’s Weekly beginning in 1936 and Esquire starting in 1939.

Jenkins was a pioneer in many now-archetypical science fiction themes. He explored parallel universe stories four years before Jack Williamson’s classic The Legion of Time came out, with “Sidewise in Time” (after which the Sidewise Award is named) in the June 1934 issue of Astounding. He also invented the “universal translator” popularized by Star Trek. And his 1946 short story “A Logic Named Joe” contains one of the first descriptions of a computer (called a “logic”) in fiction. He envisioned logics in every home, linked through a distributed system of servers (called “tanks”), to provide communications, entertainment, data access, and commerce; one character says that “logics are civilization.” Not so far off from our Internet today!

Truly, he was one of the great visionary writers the field has ever produced.

THE BOOMERANG CIRCUIT,by Murray Leinster

CHAPTER 1

Damaged Transmitter

Kim Rendell had almost forgotten that he was ever a matter-transmitter technician. But then the matter-transmitter on Terranova ceased to operate and they called on him.

It happened just like that. One instant the wavering, silvery film seemed to stretch across the arch in the public square of the principal but still small settlement on the first planet to be colonized in the Second Galaxy. The film bulged, and momentarily seemed to form the outline of a human figure as a totally-reflecting, pulsating cocoon about a moving object. Then it broke like a bubble-film and a walking figure stepped unconcernedly out. Instantly the silvery film was formed again behind it and another shape developed on the film’s surface.

Only seconds before, these people and these objects had been on another planet in another island universe, across unthinkable parsecs of space. Now they were here. Bales and bundles and parcels of merchandise. Huge containers of foodstuffs—the colony on Terranova was still not completely self-sustaining—and drums of fuel for the space-ships busy mapping the new galaxy for the use of men, and more people, and a huge tank of viscous, opalescent plastic.

Then came a pretty girl, smiling brightly on her first appearance on a new planet in a new universe, and crates of castings for more spaceships, and a family group with a pet zorag on a leash behind them, and a batch of cryptic pieces of machinery, and a man.

Then nothing. Without fuss, the silvery film ceased to be. One could look completely through the archway which was the matter-transmitter. One could see what was on the other side instead of a wavering, pulsating reflection of objects nearby. The last man to come through spoke unconcernedly over his shoulder, to someone he evidently believed just behind, but who was actually now separated from him by the abyss between island universes and some thousands of parsecs beyond.

Nobody paid any attention to matter-transmitters ordinarily. They had been in use for ten thousand years. All the commerce of the First Galaxy now moved through them. Spaceships had become obsolete, and the little Starshine—which was the first handiwork of man to cross the gulf to the Second Galaxy—had been a museum exhibit for nearly two hundred years before Kim Rendell smashed out of the museum in it, with Dona, and the two of them went roaming hopelessly among the ancient, decaying civilizations of man’s first home in quest of a world in which they could live in freedom.

* * * *

It seemed a hopeless quest, at first. Every government was absolute, and hence every ruler had become tyrannical. And the very limitations of spaceships, which had caused their supplantation by matter-transmitters, had seemed to doom their quest to futility.

But Kim had adapted the principle of the transmitter to the drive of his ship, and with the increased speed and range they’d found freedom on the prison world of Ades, where alone there was no tyranny. And later Kim had crossed to this new galaxy, and set up a transmitter here—the one which had just failed—and the exiled rebels and recalcitrants of Ades had begun to move through to a new universe where, they swore, men should be forever free.1

They planned to have Ades remain a receiving-depot for more criminals and rebels who would increase the population of the new galaxy. There should be a constant flow of them. Governments which could not be overthrown existed everywhere. They were maintained by the device of the disciplinary circuit which enabled a tyrant or a group of oligarchs to administer intolerable torture to any individual they chose, wherever he might hide upon a planet’s surface.

Revolt was utterly impossible. But there were some who revolted, nevertheless. And Ades had been a planet of hopeless exile to which such sturdy rebels could be sent as to a fate more mysterious and hence more terrible than death. On the whole, the new-comers were of the stuff of pioneers. The principal drawback was that so few women were rebels.

Events begun by the Empire of Sinab had solved even that problem of a superabundance of males, by reversing it. The Sinabian Empire had expanded by a policy of seemingly irresistible murder. By that policy, modified fighting-beams swept over a planet which was to be added to the empire, and in a single day slew every man and boy-child on it, leaving the women unharmed. And as time passed and years went by, when the women had grown numbed by their grief and then their despair that their race must die—why, then male colonists from Sinab appeared, and condescended to take the place of their victims.

They had planned to add Ades to their empire,2 but the end was the exile of the men of Sinab to a planet and a universe so remote that men had not even conceived of such a distance before. And the widows of murdered men—not sharing that exile—accepted the wiveless men of Ades as their deliverers.

From that time until now, it had seemed that only triumphs could lie before the exiles. Duplicates of the Starshine roamed among the new and unnamed stars of the Second Galaxy. Infinite opportunities lay ahead. Until now!

Now the matter-transmitter had ceased to operate. Five millions of human beings in the Second Galaxy were isolated from the First. Ades was the only planet in the home galaxy on which all men were criminals by definition, and hence were friendly to the people of the new settlements. Every single other planet—save the bewildered and almost manless planets which had been subject to Sinab—was a tyranny of one brutal variety or another.

Every other planet regarded the men of Ades as outlaws, rebels, and criminals. The people of Terranova, therefore, were not only cut off from the immigrants and supplies and the technical skills of Ades. They were necessarily isolated from the rest of the human race. And it could not be endured. And then, besides that, there were sixteen millions of people left on Ades, cut off from the hope that Terranova represented.

Kim Rendell was called on immediately. The Colony Organizer of Terranova, himself, went in person to confer and to bewail.

Kim Rendell was peacefully puttering with an unimportant small gadget when the Colony Organizer arrived. The house was something of a gem of polished plastic—Dona had designed it—and it stood on a hill with a view which faced the morning sun and the rising twin moons of Terranova.

The atmosphere-flier descended, and Dona led the Organizer to the workshop in which Kim puttered. The Organizer had had half an hour in which to think of catastrophe. He was in a deplorable state when Kim looked up from the thing with which he was tinkering.

“Enter and welcome,” he said cheerfully in the formal greeting. “I’m only amusing myself. But you look disturbed.”

The Colony Organizer bewailed the fact that there would be no more supplies from Ades. No more colonists. Technical information, urgently needed, could not be had. Supplies were called for for exploring parties, and new building-machines were desperately in demand, and the storage-reserves were depleted and could last only so long if no more came through.

“But,” said Kim blankly. “Why shouldn’t they come through?”

“The matter-transmitter’s stopped working!” The Colony Organizer wrung his hands. “If they’re still transmitting on Ades, think of the lives and the precious material that’s being lost!”

“They aren’t transmitting,” said Kim. “A transmitter and a receiver are a unit. Both have to work for either one to operate—except in the very special case of a transmitter-drive ship. But it’s queer. I’ll come take a look.”

He slipped into the conventional out-of-door garments. Dona had listened. Now she said a word or two to Kim, her expression concerned. Kim’s expression darkened.

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” he told her. “A transmitter is too simple to break down. They can get detuned, but we made the pair for Ades and Terranova especially. Their tuning elements are set in solid plastite. They couldn’t get out of tune!”

He picked up a small box. He tucked it under his arm.

“I’ll be back,” he told Dona heavily. “But I suspect you’d better pack.”

He went out to the grounded flier. The Colony Organizer took it up and across the green-clad hills of Terranova. The vegetation of Terranova is extraordinarily flexible, and the green stuff below the flier swayed elaborately in the wind. The top of the forests bowed and bent in the form of billows and waves. The effect was that of an ocean which complacently remained upraised in hillocks and had no normal surface. It was not easy to get used to such things.