2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

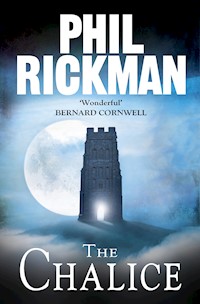

A standalone supernatural thriller from the author of the chilling Merrily Watkins Mysteries Glastonbury, legendary resting place of the Holy Grail, is a mysterious and haunting town. But when plump, dizzy Diane Ffitch returns home, it's with a sense of deep unease - and not only about her aristocratic family's reaction to her broken engagement and her New Age companions. Plans for a new motorway have intensified the old bitterness between the local people and the 'pilgrims', so already the sacred air is soured. And, as the town becomes increasingly split by violence and death, Diane, local bookseller Juanita Carey and the writer Joe Powys must now face up to the worst of all possibilities: the existence of an anti-Grail - the dark chalice. A PHIL RICKMAN STANDALONE NOVEL

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

The Chalice

PHIL RICKMAN was born in Lancashire and lives on the Welsh border. He is the author of the Merrily Watkins series, and The Bones of Avalon. He has won awards for his TV and radio journalism and writes and presents the book programme Phil the Shelf for BBC Radio Wales.

ALSO BY

PHIL RICKMAN

THE MERRILY WATKINS SERIES

The Wine of Angels Midwinter of the Spirit A Crown of Lights The Cure of Souls The Lamp of the Wicked The Prayer of the Night Shepherd The Smile of a Ghost The Remains of an Altar The Fabric of Sin To Dream of the Dead The Secrets of Pain

THE JOHN DEE PAPERS

The Bones of Avalon

OTHER TITLES

Candlenight Curfew The Man in the Moss DecemberThe Chalice

PHIL RICKMAN

The Chalice

First published in Great Britain in 1991 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Phil Rickman, 1991

The moral right of Phil Rickman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85789-691-9 Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Part One

One For Mysticism … Psychic Studies … Earth Mysteries … Esoterica

Two A Sound Thinker

Three Queen of the Hippies

Four A Fine Shiver

Five A Simple Person

Six The Weirdest Person Here

Seven Sliver of Light

Eight Only in Glastonbury

Nine No Booze, No Dope

Ten With You This Night

Eleven The Wrong God

Twelve A Little Canary

Thirteen None of It Happened

Fourteen For Mysticism … Psychic Studies … Earth Mysteries … Esoterica

Part Two

One Harmless

Two Strange Place, but Good Fun

Part Three

One Mystery

Two Like a Puma

Three Pixhill

Four The Huntress

Five Goddess

Six Flickering

Seven Synchronicity

Eight Crone

Nine Like, say, ‘ghost’

Ten His Stain

Eleven The Bell

Twelve Rescue Remedy

Thirteen A Spiritual Hothouse

Fourteen Something Hanging from It

Fifteen A Beautiful Dusk

Sixteen The Sunset Window

Seventeen Of the Heart

Part Four

One After the Fire

Two Jacket Potatoes

Three Doesn’t Matter

Four Horrid Brown Fountain

Five All for Real

Six Small Things

Seven Lady Loony, Councillor Crackpot

Eight Scorched Earth

Nine Meaningless Kind of Violence

Ten Black as Sin

Eleven Home Temple

Twelve From a High Shelf

Part Five

One Crows’ Feet Deepening

Two Our First Christmas Tree

Three The Solstice Tree

Four Pixhill’s Grave

Five Pre-ordained

Six Extreme and Everlasting

Seven Lourdes

Eight Depth of Evil

Nine Contaminant

Ten Save Them from Themselves

Eleven Blood of the Goddess

Twelve My Goddess

Thirteen Eve of Midwinter

Fourteen Pale Lightball

Fifteen Lights Go Out

Sixteen Yes, Nanny

Seventeen Ours

Eighteen Df

Epilogue

Closing Credits

The Chalice

Prologue

I had received serious injury from someone who, at considerable cost to myself, I had disinterestedly helped, and I was sorely tempted to retaliate …

Dion FortunePsychic Self-Defence, 1930

September, 1919

There she was, lying across the bed, stretched out corner to corner, as though this could relieve the cramp inside caused by the way she’d been used … trifled with and slighted, yes, and humiliated … as if, as a young woman, she was natural prey, just another little hopping bird in the hawk’s garden.

Oh! She might have felt better beating her fists into the pillow, but she’d never have excused herself for that. Not the behaviour of a trained psychoanalyst.

All the same, she would remember telling herself that if she didn’t do something about it she’d quite simply implode. So perhaps that was what started the process.

It must have been going on, somewhere, while she was persuading her body into the relaxation procedure – not easy when her stupid mind insisted on re-enacting the appalling business, over and over.

Beginning with his proposal of a small adventure for her. That boyish grin through the bristly little moustache, the kind which all the men she knew seemed to have brought back from the Great War. The bantering baritone, smooth and slick as freshly buffed mahogany.

*

‘Didn’t you know, Violet? My goodness, didn’t you know that we still had it here?’

The question causes, as he knew it would, a veritable flutter in her breast.

But Violet, still suspecting some prank, says lightly that she trusts he’s speaking metaphorically, as anybody with even a perfunctory knowledge of such matters is aware that the Holy Grail does not exist and never did.

At which he puts down his wine, spilling some. ‘The hell it doesn’t, you arrogant minx!’

‘Except, of course, as a symbol. Doubtless a sexual one.’

It’s a numbingly dull and sultry afternoon, summer seeping sluggishly into autumn, and she’s tired of his games.

‘And what would you know about symbols?’ His lips twisting in amusement. ‘Or sex, for that matter.’

The room is gloomy: tiny windows and those monstrous black beams. They have not discussed sex. Only violence and pain.

‘As much,’ she informs him casually (although she’s stung by his manner and infuriated by his blatant smirk), ‘as any advanced student of the methods of Dr Freud.’

‘Freud? That ghastly charlatan?’ He laughs, oh so confident, now that his own demons are quiet. She decides not to react.

‘A passing fad, Violet, you’ll see,’ leaning back behind his desk, handsome as the devil. ‘But please – I’m intrigued – define for me this symbolism.’

What’s his game now? Oh, she must not give in to the welling hostility. Or, worse, to that other undignified stirring which has made the leather seat feel suddenly hot where she sits. Most humiliating and hardly the response of a trained psychoanalyst.

‘So …’ He trails a finger through the spilled wine. ‘Let’s look at this. Joseph of Arimathea … uncle of Christ, provider of his tomb … begs from Pontius Pilate the cup used at the Last Supper and perhaps to collect the blood from the Cross …’

‘Yes, a pretty legend, I accept that.’

‘And then carries it with him on his missionary voyage to a place in the west of Britain, where a strange, pointed hill can be seen from the sea.’

‘Yes.’ She’s seen it herself – in dreams – as if from the sea: the mystical, conical Tor on the holy Isle of Avalon.

And although she would never admit this to him, she’s still secretly thrilled by the legend and has been many times to the place where Joseph was said to have buried the Grail, causing a spring to bubble up, the Chalice Well, which to this day runs red. Chalybeate, of course. Iron in the water.

‘Obviously,’ she says, ‘I would not dispute that Joseph and his followers came to Avalon as missionaries. Or, indeed, that he was responsible for building the first Christian church in England. This is historically feasible.’

‘How very accommodating of you, Violet.’

‘Although I rather suspect the story that Joseph had once brought the child Jesus here is no more than a romantic West Country myth illuminated by the poet Blake.’

He says nothing.

‘And surely, what Joseph introduced to these islands was a faith, not a … a trinket.’

That came out badly, sounding, even to her own ears, more than a little churlish. He smiles at her again, looking replete with superior wisdom.

She rallies. ‘The symbolism is clear. The idea of a chalice is well known in Celtic mythology – the Cauldron of Ceridwen, a crucible of wisdom, a symbol of transformation. Upon which, the legend of the Holy Grail, seen from a twentieth-century perspective, is obviously no more than a transparent Christian veneer.’

‘In which case,’ he says, musingly, after a pause, ‘the Grail would be even more significant, carrying the combined power of two great traditions, Christian and Pagan. Would it not?’

‘If there was such a thing, no doubt it would.’

‘If there was such a thing …’ He considers this for a while, hands splayed on the desk, eyes upraised to the blackened beams. ‘If there was such a thing, and it had been secretly held by the monks of Glastonbury until the Reformation …’ He stops.

His eyes are suddenly alight with zealot’s fire.

‘Oh, really.’ Violet almost sniffs. ‘Monks were always forging relics to improve the status of their abbeys. Anyway …’ Pushing back her chair and standing up. ‘I’m a psychologist. Not an historian.’

He also stands, but remains behind the desk. He seems to be considering something. ‘Very well. What if I were to show it you? What if I were to show you the Grail itself?’

He’s still wearing his uniform. Some of the men wear theirs because they have nothing else. But his wardrobe could hardly be bare or gone to moth. No, he continues to sport his captain’s uniform because he knows its power. Over women, of course.

‘Ha,’ Violet says. Uncertainly.

In spite of herself, in spite of the teachings of Dr Freud and what he has to say about the all-consuming power of sex, she is beginning, as she follows this man out of the study and down a dark, low passage, to feel quite ridiculously excited.

In those days, Violet hadn’t been terrifically good at containing emotion. Well, she was still a young woman, somewhat less experienced than her confidence might suggest.

She knew she was not what most people would call beautiful and that some men were intimidated by her direct manner. But, others – and quite often the better-looking ones, the ones whose arms might have been around slimmer waists – would seek her out. Faintly puzzled about why they found her attractive.

There had always been two sides to her, which she equated with the Celtic and the Saxon: the airy feyness and the no-nonsense earthiness. Although she’d been born in north Wales, she considered herself (because of her Yorkshire steel-working family) to be chiefly Saxon, as suggested by her flaxen hair and her solid, big-boned body. But she’d always needed the phantasmal fire of the Celts, their inbred cosmic perspective.

These two aspects had fallen unexpectedly into harmony over the past few years, during the Great War; all Europe might have been in roiling, smoking turmoil, but Violet had been curiously at peace.

Not that she was any great pacifist. She’d have quite liked to have been at the Front. To be tested. But the only women’s work there was nursing, and she was the first to admit she didn’t have the patience for it. Not then.

But staying at home had been a revelation. Elements of what she was had come together in an unexpected way. Serving in the women’s land army, raising the crops, feeding the troops: fulfilment in a healthy, practical way, but also wonderfully symbolic. With all the young, strong men away in the forces, England – the essential England, of holy hills and fertile meadows – was at last in the care of women. The girls of the land army had taken on the traditional role of Mother Goddess.

It had changed her. She still found Freud stimulating and exciting and the logic of his methodology unassailable, as far as it went. But there were areas of experience which psychoanalysis could not unveil. And she had lifted up the hem of the curtain and seen wonders.

However, to become truly initiated into the Mysteries, one needed the guidance of human beings who had been there before. And some of them could be … well, pretty unsavoury types in other respects. The sacred quest for enlightenment, it appeared, would often bring out the very worst in people.

One had to go jolly carefully, keeping one’s eyes open and, quite frankly, one’s legs together.

‘Go on then … hold it.’

Vapour is rising from a small candle on the block of stone between them.

‘No … please … this is not right!’

‘You’re wrong. It’s absolutely right. Now. For me. For us. Violet…’

It lies in a black cloth between his hands.

‘Grasp it.’

‘No!’

‘Clasp it to your breast.’ He extends his arms, the cloth and what lies in it.

‘Please … It’s black, it’s evil … I don’t …’ She’s starting to sob.

‘But it’s what you want, my dear. It’s what you’ve always wanted. This is 1919 and you’re a free and enlightened woman … a trained psychoanalyst. Primitive superstition can’t touch you now.’ Standing between her and the way out, he adds lazily, ‘And take off your clothes, why don’t you?’

And so Violet was in a fairly hellish state when she flung her soiled body on the bed, making its springs howl. In retrospect she might have been better off rampaging through the grounds, taking it out on the last of the weeds.

The bed had a light green eiderdown, and the wallpaper was salmon pink. Colours of summer. A pleasant room on a sullen autumn afternoon. But it didn’t calm her down today. The effects of such abuse did not just quietly fade.

There was an essential conflict here. One could adopt the Christian attitude, turn the other cheek and walk away: very well, I tried to help you … I counselled you, taught you how to control your nightmares from the War … and you took advantage of me. Nevertheless, not my place to be judgemental. As a psychologist.

Ha. Hardly good enough was it? Violet sighed, lay back and let her eyelids fall. The pillows were soft and cool. The back of her head felt heavy, like a bag of potatoes. She let her arms flop by her sides. The anger, still burning somewhere below her abdomen, was at odds, though not uncomfortably so, with the supine state of her body. She was, surprisingly, reaching a state of relaxation. But then, she was getting rather good at that.

Of course …

Violet smiled.

… one could simply allow oneself to go absolutely and utterly berserk.

She began a simple visualisation, letting loose her thoughts, to roam the wildest of terrain, those places of high cliffs and crashing waves, black and writhing trees against a thundery sky. As her body lay on its bed, on a sallow, sunless afternoon in the mellow, autumnal Vale of Avalon, her thoughts stalked the wintry wasteland of cruel Northern myths. In search of a suitably savage instrument of revenge. Oh yes.

She was starting to enjoy her anger and felt no guilt about this. Daylight dripped on to her eyelids like syrup. And in the cushiony hinterland of sleep, in those moments when the senses mingle and then dissolve, when fragments of whispered words are sometimes heard and strange responses sought, Violet’s rage fermented pleasurably into the darkest of wines.

‘Good dog.’

Its fur was harsh as a new hairbrush. It brushed her left arm, raising goosebumps.

It lay there quite still, as relaxed as Violet had been, but with a kind of coiled and eager tension about it. She could feel its back alongside her, its spine against her cotton shift. It was lean, but it was heavy. And it was beginning to breathe.

She didn’t really question its presence at first. It was simply there. She raised her left hand to pat it. Then the hand suddenly seized up.

So cold.

And Violet was aware that the room had gone dark.

Not dark as if she’d simply fallen asleep and the afternoon had slid away into evening. Dark as in a draining of the light, of the life-force vibrating behind colours. The most horribly negative kind of darkness.

She opened her eyes fully. It made no difference. The wallpaper was a deepening grey and the fogged light inside the window frame thick and stodgy, like a rubber mat. The eiderdown beneath her was as hard and ungiving as a cobbled street.

The fear had come upon her slowly and was all the worse for that. It chilled her insides like a cold-water enema. A rank odour soured the room. The air seemed noxious with evil, almost-visible specks of it above her like a cloud of black midges.

Drawing a breath made her body lurch against the creature lying motionless beside her in the gloom.

And motionless it stayed, for a moment.

Violet knew what she had to do. She lay as still as she could, gathering breath and her nerve.

Then she put out her left hand. Out and down. Until her fingers found the eiderdown, hard as worn stone. There was an almost liquid frigidity around her hand, over the wrist, almost to the elbow, like frogspawn in a half-frozen pond.

It was very hard to turn her head, as though her neck was in a vice, everything she held holy crying out to her not to look.

But look she did. She managed to turn her head just an inch, enough to focus on her left shoulder and follow her arm down and down to where the wrist … vanished.

Somewhere through the greyness she could detect a dim image of her fingers on the eiderdown, while the beast’s gaseous body swirled around the flesh of her arm.

As Violet began to pant with fear, it turned its grey head, and the only white light in the room was in its long, predator’s teeth and the only colour in the room was the still, cold yellow of its eyes.

I am yours.

Part One

There is such magic in the first glimpse of that strange hill that none who have the eye of vision can look upon it unmoved.

Dion FortuneAvalon of the Heart, 1934

ONE

FOR MYSTICISM … PSYCHIC STUDIES … EARTH MYSTERIES … ESOTERICA

CAREY AND FRAYNE

Booksellers High Street Glastonbury

Prop. Juanita Carey

14 November

Danny, love,

Enclosed, as promised, one copy of Colonel Pixhill’s Glastonbury Diary. More about that later. After this month’s marathon moan.

Sorry. I’m getting hopelessly garrulous, running off at the mouth, running off at the Amstrad. Put it down to Time of Life. Put this straight in the bin, if you like, I’m just getting it all off my increasingly vertical chest.

What’s put me all on edge is that Diane’s back. Diane Ffitch.

Funny how so many of my problems over the years have involved that kid. Hell, grown woman now – by the time I was her age, I’d been married, divorced, had three good years with you (and one bad), moved to Glastonbury, started a business…

I know. A lot more than I’ve done since. There. Depressed myself now. It doesn’t take much these days. Colonel Pixhill was right: Glastonbury buggers you up. But then, you knew that, didn’t you?

I’ve been trying to think if you ever met Diane. I suspect not. She was in her teens by the time our paths finally crossed (although I’d heard the stories, of course) and you were long gone by then. Although you might remember the royal visit, was it 1972, late spring? Princess Margaret, anyway – always kind of liked her, nearest thing to a rebel that family could produce. As I remember you wouldn’t go to watch. Uncool, you said. But the next day the papers had this story about the small daughter of local nob Lord Pennard, who was to have presented the princess with a bouquet.

Diane would have been about four then and already distinctly chubby. Waddles up to Margaret – I think it was at the town hall – with this sheaf of monster flowers which is more than half her size. Maggie stoops graciously to scoop up the blooms, the photographers and TV cameramen all lined up. Whereupon, Diane unceremoniously dumps the bouquet, hurls herself, in floods of tears, at the royal bosom and sobs – this was widely used in headlines next day – ‘Are you my mummy?’

Poignant stuff, you see, because her mother died when she was born. But obviously, a moment of ultimate embarrassment for the House of Pennard, the first public indication that the child was – how can I put this? – prone to imaginative excursions. Anyway, that was Diane’s fifteen minutes of national fame. The later stuff – the disappearances, the police searches, they managed to keep out of the papers. Pity, some even better pictures there, like Diane curled up with her teddy bear under a seat in Chalice Well gardens at four in the morning.

Years later she turns up at the shop looking for a holiday job. Why my shop? Because she wanted access to the sort of books her father wouldn’t have in the house – although, obviously I didn’t know that when I took her on.

But she was a good kid, no side to her.

She’s twenty-seven now. Until very recently, Lord Pennard thought he’d finally unloaded her, having sent her to develop her writing skills by training as a journalist in Yorkshire. What does that bastard care about her writing skills? It was Yorkshire that counted, being way up in the top right hand corner of the country. An old family friend of the Ffitches owns a local newspaper chain up there, and of course, the eldest son, heir to the publishing empire, was not exactly discouraged from associating with the Hon. Diane. Yes, an old-fashioned, upper-crust arranged marriage: titled daughter-in-law for solid, Northern press baron and the penurious House of Pennard safely plugged into a source of unlimited wealth.

But it’s all off. Apparently. I don’t know exactly why, and I’m afraid to ask. And Diane’s back.

When I say ‘back’, I don’t mean here at the shop. Or at Bowermead Hall. Nothing as simple as a stand-up row with Daddy, and brother Archer smarming about in the background. Oh no. Diane being Diane, she’s come down from the North in a convoy of New Age travellers.

Well, I’ve nothing against them in principle. How could I, with my background? Except that when we were hippies we didn’t make a political gesture out of clogging up the roads, or steal our food from shops, despoil the countryside, light fires made from people’s fences or claim social security for undertaking the above. Hey, am I becoming a latent Conservative or what?

Anyway, she rang. She’s with these travellers – oh sorry, ‘pagan pilgrims’ – and do I know anywhere near their holy of holies (the Tor, of course) where they could all camp legally for a few days? Otherwise they could be arrested as an unlawful assembly under the terms of the Criminal Justice Act.

Well, I don’t basically give a shit about the rest of them being nicked. But I’m thinking, Christ, Diane winds up behind bars, along comes Archer to discreetly (and smugly) bail her out with daddy’s money … I couldn’t bear that.

So I thought of Don Moulder, who farms reasonably close to the Tor. He’s got this field he’s been trying to flog as building land in some corrupt deal with Griff Daniel. Only, Mendip Council – now that Griff isn’t on it, thank God – insists, quite rightly, that it’s a green-belt site and won’t allow it. So now the aggrieved Moulder will rent out that field to anybody likely to piss the council off.

I call him up. We haggle for a while and then agree on three hundred quid. Which Diane is quite happy to pay. She says they’re ‘really nice people’ and it’s been a breath of fresh air for her, travelling the country, sleeping in the back of the van, real freedom, no pressure, no cruel father, no smug brother. And at the end of the road … Glastonbury. The Holyest Erthe in All England, where, according to the late Dion Fortune, the saints continue to live their quaintly beautiful lives amid the meadows of Avalon and – Oh God – the poetry of the soul writes itself.

(The reason I mention DF is that, for a long time, Diane was convinced that the famed High Priestess was her previous incarnation – gets complicated, doesn’t it?)

God knows what the great lady would have written had she been around today. Bloody hell, this is the New Age Blackpool! Shops that even in your time here used to sell groceries and hardware are now full of plastic goddesses and aromatherapy starter-kits. Everybody who ever turned over a tarot card or flipped the I-Ching sooner or later gets beached on the Isle of Avalon.

And the endless tourists. Not just Brits, but dozens of Americans, Japanese and Germans, all trooping around the Abbey ruins with their camcorders, in search of Enlightenment followed by a good dinner and a four-poster bed at The George and Pilgrims.

OK, I should moan. The shop’s never been more profitable. I’ve had to take on assistance at weekends (Jim Battle, nice man). But I’m not enjoying it any more, there’s the rub. I’m feeling tense all the time (mention menopause and you’re dead!!!). I see the latest freaks on the streets and I can see why the local people hated us twenty years ago. I too hate the New Age travellers blocking up Wellhouse Lane with their buses, marching up the Tor to tune into the Mystical Forces, camping up there and shitting on the grass and leaving it unburied.

And I can see why the natives still don’t trust us, because they think we’re trying to take over the town. And maybe we are, some of us. We say we’re all for unity and the kindly pagans are getting into bed with the Christians and everything, but basically we have very different values and when some local issue arises it all erupts. Like the proposed new road linking central Somerset into the Euro motorway network. Most of the natives are in favour because it will relieve traffic congestion in the small towns and villages, but the incomers see it as an invasion of their rural haven, the destruction of miles of wonderful countryside. So whichever way it goes, half of us are going to be furious.

It’s not as if even the Alternative Community is united. We pretend to be, of course – old hippies, part of that great universal movement. But we’re divided, factionalised: gay pagan groups, radical feminist pagans like The Cauldron. Everything in Glastonbury inevitably becomes EXTREME.

I lie awake, mulling over the old hippy thing – why CAN’T we all live in peace together on what’s supposed to be the Holyest Erthe in all Britain?

And then I go back and read Pixhill’s Diaries, making myself doubly miserable because we’re the sole outlet for a book nobody wants to buy on account of his Nostradamus-like warnings of impending doom, souls raging in torment, the rising of the Dark Chalice, etc., etc. Well, you just don’t say things like that about Glastonbury. Because this is a HOLY town and must therefore be immune from evil. The people who settle here want to bathe in the sacredness like some sort of spiritual Radox. They want to be soothed. They don’t want anything to dent the idyll.

Anyway, you should see a copy, as Carey and Frayne are the publishers. Let me know what you think. I’ll go now. I think I can see Jim Battle, my best male friend these days, wobbling down High Street on what appears to be a new secondhand bike and looking, as usual, in need of a drink.

Look after yourself, wish me luck with Diane and be glad your posh London outfit doesn’t have to publish anything like the enclosed!

Love,

J

TWO

A Sound Thinker

Not knowing Archer Ffitch all that well, Griff Daniel decided on restraint.

‘Dirty, drug-sodden, heathen bastards.’ Griff scratched an itchy palm on his spiky grey beard. ‘Filthy, dole-scrounging scum.’

Attached to the wooden bars of the gate at the foot of Glastonbury Tor was a framed colour photograph of a lamb with its throat torn out. Over the photo was typed,

KILLED BY A DOG NOT ON A LEAD. DOGS WHICH CHASE SHEEP CAN BE SHOT BY LAW.

‘What they wanner do, look,’ said Griff Daniel, ‘is extend that bloody ole law. ’Tisn’t as if any of the bastards’d be missed by anybody. Double barrel up the arse from fifty yards. Bam.’

‘Appealing notion.’ Archer Ffitch was in a dark suit and tie and a pair of green wellies, even though it was pretty dry underfoot for November. Not natural, this weather, was Griff’s view. Too much that was not natural hereabouts.

‘Destroying this town, Mr Archer. Every time they come there’s always a few stays behind. Squatting in abandoned flats, shagging each other behind the church, nicking everything that’s not nailed down, and you say a word to ’em, you gets all this freedom-of-the-individual baloney. Scum.’

‘Quite, quite.’ Archer with that bored, heard-it-all-before tone. But Griff knew he’d have all Archer’s attention in a minute, by God he would.

‘And the permanent ones. Alternative society? Green-culture? What’s alternative ’bout pretending the twentieth century never bloody happened? Mustn’t have a new road ’cause it means chopping a few crummy trees down. Can’t have decent new housing ’cause it leaves us with one less bloody useless field.’

‘I hear what you’re saying.’ Archer nodding gravely, like he was being interviewed on the box. ‘I’m appalled we lost a man like you from the council, and I agree. A few changes in this town are long overdue.’

Griff sniffed. ‘What they all say, with respect. Your gaffer, he’s been spouting ’bout that for years.’

‘My father?’

‘No, lad, the MP. Sir Larry.’

Archer went silent. He’d changed a lot. Gone into his thirties still lanky, overgrown schoolboyish; suddenly he’d thickened up like His Lordship, jaw darker, eyes steadier: watch out, here comes another Pennard power-pack. Griff wished his own son was like this; it pained him to think of the difference.

‘What have you heard?’ Archer’s heavy eyebrows all but meeting in the middle, like a mantelshelf, with the eyes smouldering away underneath.

Griff smiled slyly. ‘Not a well man, our Sir Larry. Might be stepping down sooner than we thinks? Make way for someone more … vigorous? That be a suitable word?’

‘Radical might be a better one,’ Archer said cautiously. ‘In the Thatcher sense, of course.’

‘Ah.’ Griff gave his beard a thoughtful massage. ‘Could be what the place needs. Depending, mind, on what this … radical newcomer is offering to us in the, er, business community.’

‘I understand.’ Archer was gazing past Griff, up the Tor to where the tower was. Erected by the old monks back in the Middle Ages, that tower, to claim the hill for Christ. Dedicated to St Michael, the dragon-slayer, to keep the bloody heathens out. Pity it hadn’t worked.

‘Can’t see a soul up there,’ Archer said. ‘You are sure about this, Griff?’

‘Ah.’ Griff decided it was time to dump his manure and watch the steam. ‘Got it a bit wrong when I phoned you, look. They’re not here. Yet. All camped down in Moulder’s bottom field. Clapped-out ole buses and vans, no tax, no insurance. Usual unwashed rabble, green hair, rings through every orifice.’

‘Sounds enough like mass-trespass for me.’ Archer pulled his mobile phone out of his inside pocket, flipping it open. ‘OK, right. Why don’t I get this dealt with immediately, yah? Invoke the Act, have the whole damn lot charged.’

‘Aye.’ Griff nodded slowly. ‘But charged what with?’

The phone had played what sounded like the opening beeps of Three Blind Mice before Archer’s finger froze, quivering with irritation.

Griff leaned back against the gate and took his time re-reading the National Trust sign: Please avoid leaving litter, lighting fires, damaging trees.

‘Bastards are legal, Mr Archer. In Moulder’s field with Moulder’s permission. In short, Moulder’s been paid.’

‘These vagrants have money?’

‘One of ’em does. Young woman it was stumped up the readies, so I hear. One as even Moulder figured he could trust.’

Griff leaned back against the gate, gave his beard a good rub.

‘Quite a distinctive-looking young lady, they d’say.’

‘Spit it out, man.’ Archer was going to have to deal with this tendency to impatience with the lower orders. MPs should be good listeners.

‘Of … should we say generous proportions? And she don’t talk like your usual hippy rabble.’

Archer was hard against the light, solid and cold as the St Michael tower.

‘What are you saying, Mr Daniel?’

Looking a bit dangerous. Like he could handle himself, same as his old man. Don’t push it, Griff decided.

‘Well, all right. It’s Miss Diane. Come rolling into town with the hippies. In a white van. Big pink spots on it.’

Archer said nothing, just loomed over him, best part of a foot taller. Moisture on his thick lips now.

‘Your little sister, Mr Archer.’ Little. Jesus, she must be pushing thirteen stone. ‘She come in with ’em and she rented ’em a campsite so they wouldn’t get arrested. Don’t ask me why.’

‘If this is a joke, Mr Daniel … Because my sister’s …’

‘Up North. Aye. About to get herself hitched. Except she’s in Moulder’s bottom field. In a van with big pink spots. No joke. No mistake, Mr Archer.’

Archer was as still as the old tower. ‘How many other people know about this?’

‘Only Moulder, far’s I know. Who, if any, like, action happens to be taken, requests that he be kept out of it, if you understand me.’

No change of expression, no inflexion in his voice, Archer said, ‘I’m grateful for this. I won’t forget.’

‘Well,’ Griff said. ‘Long as we understands each other. I think we want the same things for this town. Like getting it cleaned up. Proper shops ’stead of this New Age rubbish. Cranks and long-hairs out. Folk in decent clothes. Decent houses on decent estates. Built by, like, decent firms. And, of course, the new road to get us on to the Euro superhighway, bring in some proper industry. Big firms. Executive housing.’

Archer nodding. ‘You’re a sound thinker, Griff. We all need a stake in the twenty-first century.’

‘Oh, and one other thing I want…’

Archer folded his arms and smiled.

‘I want my council seat back off that stringy little hippy git Woolaston,’ said Griff.

Archer patted the leather patch at the shoulder of Griff’s heavy, tweed jacket. ‘Let’s discuss this further. Meanwhile, I have a meeting tonight. With a certain selection committee. After which I may be in a better position to, ah, effect certain changes.’

‘Ah. Best o’ luck then, Mr Archer.’

‘Thank you. Er …’ Archer looked away again. ‘Diane’s … illness … has caused us considerable distress. It’s good to know she has chaps like you on her side.’

‘And on yours, Archer,’ Griff Daniel said. ‘Naturally.’

As Archer drove off in his grey BMW, Griff looked to the top of the unnaturally steep hill, glad to see there was still nobody up there, no sightseers, no joggers, no kids. And no alternative bastards with dowsing rods and similar crank tackle.

He hated the bloody Tor.

Not much over five hundred feet high when you worked it out. Only resembled some bloody green Matterhorn, look, on account of most of the surrounding countryside was so flat, having been under the sea, way back.

So nothing to it, not really.

But look at the trouble it caused. Bloody great millstone round this town’s neck. Thousands of tourists fascinated by all that cobblers about pagan gods and intersecting lines of power.

If it wasn’t for all that old balls, there’d be no New Age travellers, no hippy refugees running tatty shops, no mid-summer festivals and women dancing around naked, no religious nuts, no UFO-spotters. Glastonbury Tor, in fact, was a symbol of what was wrong with Britain.

Also the National Trust bastards hadn’t even given him the contract for installing the new pathway and steps.

Griff Daniel went back to his truck. G Daniel & Co. Builders. It would maybe have said … & Son. If the so-called son hadn’t disgraced the family name.

When it came down to it, the only way you were going to get rid of the riff-raff was by getting rid of the damn Tor. He imagined a whole convoy of JCBs gobbling into the Tor like it was a Walnut Whip, the hill giving way, the tower collapsing into dusty, medieval rubble.

All the way back to his yard on the edge of the industrial estate, Griff Daniel kept thinking about this. It wasn’t possible, of course, not under any conceivable circumstances. You couldn’t, say, put the new road through it, not with a scheduled ancient monument on top, and also it was far too big a national tourist attraction.

But it did make you think.

THREE

Queen of the Hippies

It was rather an antiquated bicycle, a lady’s model with no crossbar, a leatherette saddle bag and a metal cover over the chain. Terribly sedate, an elderly spinster’s sort of machine, fifteen quid from On Your Bike, over at Street. But Jim could get his feet to the pedals without adjusting the seat, and, more to the point, it was the kind of bicycle no youngster would want to be seen dead on.

So at least he could park it in town with an odds-on chance of it not being nicked.

Jim unloaded himself from the bike outside Burns the Bread, in the part of Glastonbury High Street where the Alternative Sector was rapidly chasing the few remaining locally owned shops up the hill.

He was puffing a bit and there was sweat on his forehead. It was rather close and humid. And November, amazingly. He pushed the bike across the pavement and into a narrow alleyway next to the bookshop called Carey and Frayne. Got out his handkerchief to wipe his face, the alleyway framing a neat little streetscene from a viewpoint he’d never noticed before – quite a nice one, because …

… by God …

… above the weathered red-tiled roofs and brick chimney stacks of the shops across the street reared the spiked and buttressed Norman tower of the town centre church, St John’s, and it had suddenly struck Jim that the tower’s top tier, jagged in the florid, late-afternoon sun, resembled a crown of thorns.

While, in the churchyard below, out of sight from here, there was one of the holy thorns, grafted from the original on Wearyall Hill. It was as if the Thorn had worked its way into the very fabric of the church, finally thrusting itself in savage symbolism from the battlements.

Yes, yes, yes. Jim started to paint rapidly in his head, reforming sculpted stone into pronged and twisted wildwood. But keeping the same colours, the pink and the ochre and the grey, amid the elegiac embers of the dying sun.

By God, this buggering town … just when you thought you had it worked out, it would throw a new image at you like a well-aimed brick. Jim was so knocked-sideways he almost forgot to chain his bike to the drainpipe. Almost.

Twenty feet away, a youth sat in a dusty doorway fumbling a guitar. Jim gave him a hard look, but he seemed harmless enough. The ones with guitars usually were, couldn’t get up to much trouble with an instrument that size to lug around. Penny-whistlers, now, they were the ones you had to watch; they could shove the things down their belts in a second, leaving two hands free for thieving.

Over the past eighteen months, Jim had had three bikes stolen, two gone from the town centre, one with the padlocked chain snipped and left in the gutter. Metal cutters, by God! Thieves with metal cutters on the streets of Glastonbury.

‘Jim, you’re painting!’

‘No, I’m not.’ Reacting instinctively. For half his adult life, painting had been something to deny – bloody Pat shrieking, How many bills is that going to pay?

‘New bike, I see.’ The most beautiful woman in Glastonbury bent over the bike, stroking the handlebars. ‘Really rather suits you.’

‘You calling me an old woman?’ Jim pulled off his hat. ‘I’ll have you know, my girl, I’ve just ridden the buggering thing all the way back from Street in the slipstream of a string of transcontinental juggernauts half the size of the QE2. Bloody Europe comes to Somerset.’

‘Just be thankful that bikes are still allowed on that road. Come the new motorway you’ll be banned for ever.’

‘Won’t happen. Too much opposition.’

‘Oh sure. Like the Government cares about the Greens and the old ladies in straw hats.’ She straightened up, hands on her hips, and a bloody fine pair of hips they were. ‘Tea?’

‘Well … or something.’ Jim followed her into the sorcerer’s library she called a bookshop. He helped out here two or three days a week, trying not to look too closely at what he was selling.

He glared suspiciously at one of those cardboard dumpbin things displaying a new paperback edition of the silly novels of Glastonbury’s own Dion Fortune. Awful, crass covers – sinister hooded figures standing over stone altars and crucibles.

‘Over the top. The artwork. Tawdry. Way over the top.’

‘Isn’t everything in Glastonbury these days?’

Well, you aren’t, for a start, Jim thought. He wondered whether something specific had happened to make Juanita distance herself from the sometimes-overpowering spirituality of the town and from the books she sold. You didn’t open a shop like this unless you were of a strongly mystical persuasion, but these days she answered customers’ questions lightly and without commitment, as if she knew it was all nonsense really.

Jim let her steer him into the little parlour behind the shop, past the antiquarian section, where the books were kept behind glass, most of them heavy magical manuals from the nineteenth century. Jim had flicked one open the other week and found disturbingly detailed instructions ‘for the creation of elemental spirits’. He suspected it didn’t mean distilling your own whisky.

Which reminded him. ‘Erm … that Laphroaig you had. Don’t suppose there’s a minuscule drop left?’

‘That rather depends how many minuscule drops you’ve had already,’ Juanita said cautiously. Damn woman knew him rather too well.

‘One. Swear to God. Called at a pub called the Oak Tree or something. Nerves shot to hell after a run-in with a container lorry from Bordeaux. One small Bells, I swear it.’

She looked dubious, puckering her lovely nose. In the lingering warmth of this year’s strange, post-Indian summer, she was wearing a lemon yellow off-the-shoulder thing, showing all her freckles. Well, as many of them as he’d ever seen.

‘Just that you’re looking … not exactly un-flushed, Jim.’

‘Hmmph,’ said Jim. He let Juanita sit him down in an armchair, planting a chunky tumbler in his drinking and painting hand. She had quite a deep tan from sunning herself reading books on the balcony at the back. While most women her age were going frantic about melanoma, Juanita snatched all the sun she could get. Must be the Latin ancestry.

Watching her uncork the Laphroaig bottle with a rather suggestive thopp, Jim thought, Ten years … ten years younger would do it. Ten years, maybe fifteen, and she’d be at least within reach.

He coughed, hoping nothing showed. ‘Erm … Happened to cycle past Don Moulder’s bottom field on the way back. Guess bloody what.’

‘New Age travellers?’

‘Nothing gets past you, does it?’ Jim held out his glass. ‘Arrogant devils. Bloody thieving layabouts.’

‘Not quite all of them.’

As she leaned over to pour his drink, Jim breathed in a delightful blend of Ambre Solaire and frank feminine sweat, the mixture sensuously overlaid with the smoky peatmusk of the whisky. Aaaaah … the dubious pleasure of being sixty-two years old, unattached again, and with all one’s senses functioning, more or less.

‘I’m sorry …’ Shaking himself out of it and feeling the old jowls wobble. ‘What did you just say?’

‘I said at least one of them isn’t a thief. Besides, oddballs have always drifted towards Glastonbury. Look at me. Look at you.’

‘Yes, but, Juanita, the essential difference here is that we saved up our hard-earned pennies until we could do it in a respectable way. We didn’t just get an old bus from a scrapyard and enough fuel to trundle it halfway across the country before it breaks down and falls to pieces in some previously unsullied beauty spot. You see, what gets me is how these characters have the bare-faced cheek …’

‘Because Diane’s with them.’

‘… to call themselves friends of the buggering planet, when they … What did you say …?’ Jim had to steady the Laphroaig with his other hand.

Juanita poured herself a glass of probably overpriced white wine from Lord Pennard’s vineyard and lowered herself into a chintzy old rocking chair by the Victorian fireplace. There was a small woodstove tucked into the fireplace now, unlit as yet, but with a few autumn logs piled up ready for the first cold day.

Jim said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t quite understand. You say Diane’s back? Diane’s with them? But I thought …’

‘We all did. Which is …’ Juanita sighed. ‘… I suppose, why I got them the field.’

Jim was bewildered. ‘You got them the buggering field?’

He’d thought she was over all that. Might have been Queen of the Hippies 1972, but she was fully recovered now, surely to God.

Juanita said, ‘Comes down to the old question: if I don’t try and help her, who else is going to?’

‘But I thought she was working in Yorkshire.’ The idea of Diane training to be a journalist had struck Jim as pretty unlikely at the time, considering the girl’s renowned inability to separate fact from fantasy. ‘I thought she was getting married. Peter somebody.’

‘Patrick. It’s off. Abandoned her job, everything.’

‘To become a New Age buggering traveller?’

‘Not exactly. As she put it, she kind of hitched a lift. They were making their way here, and she …’

Juanita reached for her cigarettes.

‘… Oh dear. She said it was calling her back.’

Jim groaned. ‘Not again. Dare I ask what, specifically, was calling her back?’

‘The Tor.’ Juanita lit a cigarette. ‘What else?’

Jim was remembering that time the girl had gone missing and they’d found her just before dawn under the Thorn on Wearyall Hill, in her nightie and bare feet. What was she then, fifteen? He sank the last of the Laphroaig. He was too old for this sort of caper.

‘Lady Loony,’ he said. ‘Do people still call her that?’

FOUR

A Fine Shiver

The ancient odour had drifted in as soon as Diane wound down the van window, and it was just so … Well, she could have wept. How could she have forgotten the scent?

The van had jolted between the rotting gateposts into Don Moulder’s bottom field. It had bounced over grass still ever so parched from a long, dry summer and spiky from the harvest. Diane had turned off the engine, sat back in the lumpy seat, closed her eyes and let it reach her through the open window: the faraway fragrance of Holy Avalon.

Actually, she hadn’t wound down the window, as such. Just pulled out the folded Rizlas packet which held the glass in place and let it judder to its favourite halfway position. It was rather an old van, a Ford something or other – used to be white all over but she’d painted big, silly pink spots on it so it wouldn’t stand out from the rest of the convoy.

The smell made her happy and sad. It was heavy with memories and was actually a blend of several scents, the first of them autumn, a brisk, mustardy tang. And then wood-smoke – there always seemed to be woodsmoke in rural Somerset, much of it applewood which was rich and mellow and sweetened the air until you could almost taste it.

And over that came the most elusive ingredient: the musk of mystery, a scent which summoned visions. Of the Abbey in the evening, when the saddened stones grew in grace and sang to the sunset. Of wind-whipped Wearyall Hill with the night gathering in the startled tangle of the Holy Thorn. Of the balmy serenity of the Chalice Well garden. And of the great enigma of the West: Glastonbury Tor.

Diane opened her eyes and looked up at the huge green breast with its stone nipple.

She wasn’t the only one. All around, people had been dropping out of vans and buses, an ambulance, a stock wagon. Gazing up at the holy hill, no more than half a mile away. Journey’s end for the pagan pilgrims. And for Diane Ffitch, who called herself Molly Fortune because she was embarrassed by her background, confused about her reason for returning and rather afraid, actually.

Dusk was nibbling the fringes of Don Moulder’s bottom field when the last few vehicles crawled in. They travelled in smaller groups nowadays, because of the law. An old Post Office van with a white pentacle on the bonnet was followed by Mort’s famous souped-up hearse, where he liked to make love, on the long coffin-shelf. Love is the law, Mort said. Love over death.

Headlice and Rozzie arrived next in the former Bolton Corporation single-decker bus repainted in black and yellow stripes, like a giant bee.

‘Listen, I’ve definitely been here before!’ Headlice jumped down, grinning eerily through teeth like a broken picket fence. He was about nineteen or twenty; they were so awfully young, most of these people. At that age, Diane thought, you could go around saying you were a confirmed pagan, never giving a thought to what it really meant.

‘I mean, you know, not in this life, obviously,’ Headlice said. ‘In a past life, yeah?’ Looking up expectantly, as though he thought mystic rays might sweep him away and carry him blissfully to the top of the holy hill. ‘Hey, you reckon I was a monk?’

He felt at the back of his head. Where a monk’s tonsure would be, Headlice had a swastika tattoo, re-exposed because of the affliction which had led to his extremely severe haircut and his unfortunate nickname.

Rozzie made a scoffing noise. ‘More like one of the friggin’ peasants what carted the stones up the hill.’

She’d told Diane that the swastika was a relic of Headlice’s days as some sort of a teenage neo-fascist, neo-skinhead. Headlice, however, pointed out that the original swastika was an ancient pagan solar symbol. Which was why he’d had one tattooed on the part of him nearest the sun, see?

He turned away and kicked at the grass. His face had darkened; he looked as if he’d rather be kicking Rozzie. She was a Londoner; he was from the North. She was about twenty-six. Although they shared a bus and a bed, she seemed to despise him awfully.

‘I could’ve been a fuckin’ monk,’ Headlice said petulantly. Despite the democratic, tribal code of the pilgrims, he was obviously very conscious of his background, which made Diane feel jolly uncomfortable about hers. She’d been trying to come over sort of West Country milkmaidish, but she wasn’t very good at it, probably just sounded frightfully patronising.

‘Or a bird,’ she said. ‘Perhaps you were a little bird nesting in the tower.’ She felt sorry for Headlice.

‘Cute. All I’m sayin’ is, I feel … I can feel it here.’ Punching his chest through the rip in his dirty denim jacket. ‘This is not bullshit, Mol.’

Diane smiled. On her own first actual visit to the Tor – or it might have been a dream, she couldn’t have been more than about three or four – there’d been sort of candyfloss sunbeams rolling soft and golden down the steep slopes, warm on her sandals. She wished she could still hold that soft, undemanding image for more than a second or two, but she supposed it was only for children. Too grownup to feel it now.

Also she felt too … well, mature, at twenty-seven, to be entirely comfortable among the pilgrims although a few were ten or even twenty years older than she was and showed every line of it. But even the older women tended to be fey and child-like and stick-thin, even the ones carelessly suckling babies.

Stick-thin. How wonderful to be stick-thin.

‘What it is …’ Headlice said. ‘I feel like I’m home.’

‘What?’ Diane looked across to the Tor, with the church tower without a church on its summit. Oh no. It’s not your home at all, you’re just passing through. I’m the one who’s …

Home? The implications made her feel faint. She wobbled about, wanting to climb back into the van, submerge like a fat hippo in a swamp. Several times on the journey, she’d thought very seriously about dropping out of the convoy, turning the van around and dashing back to Patrick, telling him it had all been a terrible, terrible mistake.

And then she’d seen the vinegar shaker on the high chipshop counter at lunchtime and a spear of light had struck it and turned it into a glistening Glastonbury Tor. Yes! she’d almost shrieked. Yes, I’m coming back!

With company. There must be over thirty pilgrims here now, in a collection of vehicles as cheerful as an old-fashioned circus. At least it had been cheerful when she’d joined the convoy on the North Yorkshire moors – that old army truck sprayed purple with big orange flowers, the former ambulance with an enormous eye painted on each side panel, shut on one side, wide open on the other. But several of the jollier vehicles seemed to have dropped out. Broken down, probably. Well, they were all frightfully old. And fairly drab now, except for Diane’s van and Headlice’s bee-striped bus.

Mort’s hearse had slunk in next to the bus. There was a mattress in the back. Mort had offered to demonstrate Love over Death to Diane once; she’d gone all flustered but didn’t want to seem uncool and said it was her period.

Mort climbed out. He wore a black leather jacket. He punched the air.

‘Yo, Headlice!’

‘OK, man?’

‘Tonight, yeah?’

‘Yeah,’ said Headlice. ‘Right.’

Mort wandered off down the field and began to urinate casually into a gorse bush to show off the size of his willy.

Diane turned away. Despite the unseasonal warmth, it had been a blustery day and the darkening sky bore obvious marks of violence, the red sun like a blood-bubble in an open wound and the clouds either runny like pus or fluffy in a nasty way, like the white stuff that grew on mould.

Diane said, ‘Tonight?’

‘Up there.’ Headlice nodded reverently at the Tor where a low, knife-edge cloud had taken the top off St Michael’s tower, making it look, Diane thought – trying to be prosaic, trying not to succumb – like nothing so much as a well-used lipstick sampler in Boots.

But this was the terminus. They’d travelled down from Yorkshire, collecting pilgrims en route, until they hit the St Michael Line, which focused and concentrated energy across the widest part of England. They might have carried on to St Michael’s Mount at the tip of Cornwall; but, for pagans, the Tor was the holy of holies.

‘What are you – we – going to do?’ Diane pulled awkwardly at her flouncy skirt from the Oxfam shop, washed-out midnight blue with silver half-moons on it.

‘Shit, Mol, we’re pagans, right? We do what pagans do.’

‘Which means he don’t know.’ Rozzie cackled. Her face was round but prematurely lined, like a monkey’s. Ropes of black beads hung down to her waist.

‘And you do, yeah?’ Headlice said.

Rozzie shrugged. Diane waited; she didn’t really know what pagans did either, apart from revering the Old Gods and supporting the Green Party. They would claim that Christianity was an imported religion which was irrelevant to Britain.

But what would they actually do?

‘I wouldn’t wanna frighten you.’ Rozzie smirked and swung herself on to the bus.

From across the field came the hollow sound of Bran, the drummer, doing what he did at every new campsite, what he’d done at every St Michael Church and prehistoric shrine along the Line: awakening the earth.

Diane looked away from the Tor, feeling a trickle of trepidation. She supposed there’d be lights up there tonight. Whether it was just the bijou flickerings of torches and lanterns, the oily glow of bonfires and campfires …

… or the other kind. The kind some people called UFOs and some said were earth-lights, caused by geological conditions.

But Diane thought these particular lights were too sort of personal to be either alien spacecraft or natural phenomena allied to seismic disturbance. It was all a matter of afterglow. Not in the sky; in your head. In the very top of your head at first, and then it would break up into airy fragments and some would lodge for a breathtaking moment in your throat before sprinkling through your body like a fine shiver.

Bowermead Hall, you see, was only three and a half miles from the town and, when she was little, the pointed hill crowned by the St Michael tower – the whole thing like a wine-funnel or a witch’s hat – seemed to be part of every horizon, always there beyond the vineyards. Diane’s very earliest sequential memory was looking out of her bedroom window from the arms of Nanny One and seeing a small, globular light popping out of the distant tower, like a coloured ball from a Roman candle. Ever so pretty, but Nanny One, of course, had pretended she couldn’t see a thing. She’d felt Diane’s forehead and grumbled about a temperature. What had happened next wasn’t too clear now, but it probably involved a spoonful of something tasting absolutely frightful. You’re a very silly little girl. Too much imagination is not good for you.

For a long time, Diane had thought imagination must be a sort of ice-cream; the lights too – some as white as the creamy blobs they put in cornets.

Years later, when she was in her teens, one of the psychologists had said to her, You were having rather a rough time at home, weren’t you, Diane? I mean, with your father and your brother. You were feeling very lonely and … perhaps … unwanted, unloved? Do you think that perhaps you were turning to the Tor as a form of …

‘No!’ Diane had stamped her foot. ‘I saw those lights. I did.’

And now the Tor had signalled to her across Britain. Called her back. But it wasn’t – Diane thought of her father and her brother and that house, stiff and unforgiving as the worst of her schools – about pretty lights and candyfloss sunbeams. Not any more.