18,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Marion Boyars

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Digby was a natural writer, as entertaining as instructive. Many of the recipes are for drinks, particularly of meads or metheglins, but the culinary material provides a remarkable conspectus of accepted practice among court circles in Restoration England, with extra details supplied from Digby's European travels. The editors also include the inventory of Digby's own kitchen in his London house, discovered amongst papers now deposited in the British Library; and they have provided a few modern interpretations of Digby's recipes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Frontispiece: Sir Kenelm Digby, by Anthony van Dyck (Iconography, 1645). Photograph by courtesy of the British Museum.

This edition published in 2010, by Prospect Books, Allaleigh House, Blackawton, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7DL.

The hardback edition was previously published by Prospect Books in 1997.

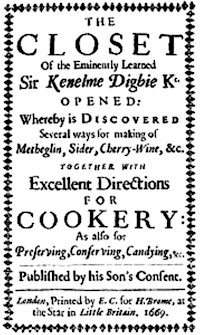

The text is that of the first edition, published by H. Brome, at the Star in Little Britain, London, 1669.

© 1997, editorial and introductory matter, Jane Stevenson and Peter Davidson.

The editors assert their right to be identified as editors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue entry of this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-903018-70-5 ePub ISBN: 978-1-909248-21-2. PRC ISBN: 978-1-909248-22-9.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the Short Run Press, Exeter.

CONTENTS

Table of Receipts

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The text

To the Reader

The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Opened

The Table

The appendices and supporting material

Appendix I: Notes of textual variations and supplements from George Hartman, The True Preserver and Restorer of Health…

Appendix II: Biographies of the donors of receipts and other persons noticed in the text

Appendix III: Extracts from British Library Add ms 38,175, ff.48r–50v, an inventory of Digby’s London house

Appendix IV: Some receipts, modernized

Glossary

Index

TABLE OF RECEIPTS

A RECEIPT TO MAKE METHEGLIN AS IT IS MADE AT LIEGE, COMMUNICATED BY MR. MASILLON

WHITE METHEGLIN OF MY LADY HUNGERFORD: WHICH IS EXCEEDINGLY PRAISED

SOME NOTES ABOUT HONEY

MR. CORSELLISES ANTWERP MEATH

TO MAKE EXCELLENT MEATHE

A WEAKER, BUT VERY PLEASANT, MEATHE

AN EXCELLENT WHITE MEATHE

A RECEIPT TO MAKE A TUN OF METHEGLIN

THE COUNTESS OF BULLINGBROOK’S WHITE METHEGLIN

MR. WEBBES MEATH

MY OWN CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAKING OF MEATHE

SACK WITH CLOVE-GILLY FLOWERS

METHEGLIN COMPOSED BY MY SELF OUT OF SUNDRY RECEIPTS

MY LADY GOWERS WHITE MEATHE USED AT SALISBURY

SIR THOMAS GOWER’S METHEGLIN FOR HEALTH

METHEGLIN FOR TASTE AND COLOUR

AN EXCELLENT WAY OF MAKING WHITE METHEGLIN

ANOTHER WAY OF MAKING WHITE METHEGLIN

ANOTHER WAY

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

STRONG MEAD

A RECEIPT FOR MAKING OF MEATH

MY LORD HOLLIS HYDROMEL

A RECEIPT FOR WHITE METHEGLIN

HYDROMEL AS I MADE IT WEAK FOR THE QUEEN MOTHER

SEVERAL WAYS OF MAKING METHEGLIN

MY LADY MORICES MEATH

MY LADY MORICE HER SISTER MAKES HER’S THUS:

TO MAKE WHITE MEATH

SIR WILLIAM PASTON’S MEATHE

ANOTHER PLEASANT MEATHE OF SIR WILLIAM PASTON’S

ANOTHER WAY OF MAKING MEATH

SIR BAYNAM THROCKMORTON’S MEATHE.

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

A RECEIPT FOR MAKING OF MEATH

MY LADY BELLASSISES MEATH

ANOTHER METHEGLIN

MR. PIERCE’S EXCELLENT WHITE METHEGLIN

AN EXCELLENT WAY TO MAKE METHEGLIN, CALLED THE LIQUOR OF LIFE, WITH THESE FOLLOWING INGREDIENTS

TO MAKE GOOD METHEGLIN

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN OF SIR JOHN FORTESCUE

A RECEIPT FOR MEATHE

MY LORD GORGE HIS MEATHE

THE LADY VERNON’S WHITE METHEGLIN

SEVERAL SORTS OF MEATH, SMALL AND STRONG

TO MAKE MEATH

SIR JOHN ARUNDEL’S WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE A MEATH GOOD FOR THE LIVER AND LUNGS

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

A VERY GOOD MEATH

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

A MOST EXCELLENT METHEGLIN

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN OF THE COUNTESS OF DORSET

ANOTHER WAY TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

A RECEIPT TO MAKE GOOD MEATH

ANOTHER TO MAKE MEATH

ANOTHER RECIPE

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

ANOTHER SORT OF METHEGLIN

MY LORD HERBERT’S MEATH

ANOTHER WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE SMALL METHEGLIN

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

AN EXCELLENT METHEGLIN

TO MAKE WHITE MEATHE

ANOTHER TO MAKE MEATHE

ANOTHER VERY GOOD WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

ANOTHER SORT OF MEATH

TO MAKE VERY GOOD METHEGLIN

TO MAKE MEATH

TO MAKE WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE SMALL WHITE MEATH

A RECEIPT TO MAKE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

MEATH FROM THE MUSCOVIAN AMBASSADOUR’S STEWARD

TO MAKE MEATH

A RECEIPT TO MAKE WHITE MEATH

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE HONEY DRINK

THE EARL OF DENBIGH’S METHEGLIN

TO MAKE MEATH

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

ANOTHER MEATH

ANOTHER

ANOTHER

ANOTHER RECEIPT

TO MAKE METHEGLIN THAT LOOKS LIKE WHITE-WINE

TO MAKE WHITE METHEGLIN

TO MAKE A SMALL METHEGLIN

TO MAKE MEATH

METHEGLIN OR SWEET DRINK OF MY LADY STUART

A METHEGLIN FOR THE COLICK AND STONE OF THE SAME LADY

A RECEIPT FOR METHEGLIN OF MY LADY WINDEBANKE

ANOTHER OF THE SAME LADY

TO MAKE METHEGLIN

MEATH WITH RAISINS

MORELLO WINE

CURRANTS-WINE

SCOTCH ALE FROM MY LADY HOLMBEY

TO MAKE ALE DRINK QUICK

TO MAKE CIDER

A VERY PLEASANT DRINK OF APPLES

SIR PAUL NEALE’S WAY OF MAKING CIDER

DOCTOR HARVEY’S PLEASANT WATER CIDER, WHEREOF HE USED TO DRINK MUCH, MAKING IT HIS ORDINARY DRINK

ALE WITH HONEY

SMALL ALE FOR THE STONE

APPLE DRINK WITH SUGAR, HONEY, &c

TO MAKE STEPPONI

WEAK HONEY-DRINK

MR. WEBB’S ALE AND BRAGOT

THE COUNTESS OF NEWPORT’S CHERRY WINE

STRAWBERRY WINE

TO MAKE WINE OF CHERRIES ALONE

TO MAKE A SACK POSSET

ANOTHER

A PLAIN ORDINARY POSSET

A SACK POSSET

A BARLEY SACK POSSET

MY LORD OF CARLILE’S SACK-POSSET

A SYLLABUB

A GOOD DISH OF CREAM

AN EXCELLENT SPANISH CREAM

ANOTHER CLOUTED CREAM

MY LORD OF S. ALBAN’S CRESME FOUETTEE

TO MAKE THE CREAM CURDS

TO MAKE CLOUTED CREAM

TO MAKE A WHIP SYLLABUB

TO MAKE A PLAIN SYLLABUB

CONCERNING POTAGES

PLAIN SAVOURY ENGLISH POTAGE

POTAGE DE BLANC DE CHAPON

TO MAKE SPINAGE-BROTH

ORDINARY POTAGE

BARLEY POTAGE

STEWED BROTH

AN ENGLISH POTAGE

ANOTHER POTAGE

PORTUGAL BROTH, AS IT WAS MADE FOR THE QUEEN

NOURISSANT POTAGE DE SANTÉ

POTAGE DE SANTÉ

POTAGE DE SANTÉ

POTAGE DE SANTÉ

TEA WITH EGGS

NOURISHING BROTH

GOOD NOURISHING POTAGE

WHEATEN FLOMMERY

PAP OF OAT-MEAL

PANADO

BARLEY PAP

OAT-MEAL PAP. SIR JOHN COLLADON

RICE AND ORGE MONDÉ

SMALLAGE GRUEL

ABOUT WATER GRUEL

AN EXCELLENT AND WHOLESOME WATER-GRUEL WITH WOOD-SORREL AND CURRANTS

THE QUEENS BARLEY-CREAM

PRESSIS NOURISSANT

BROTH AND POTAGE

PAN COTTO

MY LORD LUMLEY’S PEASE-PORAGE

BROTH FOR SICK AND CONVALESCENT PERSONS

AN EXCELLENT POSSET

PEASE OF THE SEEDY BUDS OF TULIPS

BOILED RICE DRY

MARROW SOPS WITH WINE

CAPON IN WHITE-BROTH

TO BUTTER EGGS WITH CREAM

TO MAKE COCK-ALE

TO MAKE PLAGUE-WATER

ANOTHER PLAGUE-WATER

TO MAKE RASBERY-WINE

TO KEEP QUINCE ALL THE YEAR GOOD

TO MAKE A WHITE-POT

TO MAKE AN HOTCHPOT

ANOTHER HOTCHPOT

TO STEW BEEF

ANOTHER TO STEW BEEF

TO STEW A BREAST OF VEAL

SAUCE OF HORSE RADISH

THE QUEENS HOTCHPOT FROM HER ESCUYER DE CUISINE, MR. LA MONTAGUE

A SAVOURY AND NOURISHING BOILED CAPON DEL CONTE DI TRINO, À MILANO

AN EXCELLENT BAKED PUDDING

MY LADY OF PORTLAND’S MINCED PYES

ANOTHER WAY OF MAKING EXCELLENT MINCED PYES OF MY LADY PORTLANDS

MINCED PYES

TO ROST FINE MEAT

SAVOURY COLLOPS OF VEAL

A FRICACEE OF LAMB-STONES, OR SWEET-BREADS, OR CHICKEN, OR VEAL, OR MUTTON

A NOURISHING HACHY

EXCELLENT MARROW-SPINAGE-PASTIES

TO PICKLE CAPONS MY LADY PORTLAND’S WAY

VERY GOOD SAUCE FOR PARTRIDGES OR CHICKEN

TO MAKE MINCED PYES

TO MAKE A FRENCH BARLEY POSSET

TO MAKE PUFF-PAST

TO MAKE A PUDDING WITH PUFF-PAST

TO MAKE PEAR-PUDDINGS

MARROW-PUDDINGS

TO MAKE RED DEAR

TO MAKE A SHOULDER OF MUTTON LIKE VENISON

TO STEW A RUMP OF BEEF

TO BOIL SMOAKED FLESH

A PLAIN BUT GOOD SPANISH OGLIA

VUOVA LATTATE

VUOVA SPERSA

TO MAKE EXCELLENT BLACK-PUDDINGS

A RECEIPT TO MAKE WHITE PUDDINGS

TO MAKE AN EXCELLENT PUDDING

SCOTCH COLLOPS

TO ROST WILD-BOAR

PYES

BAKED VENISON

AN EXCELLENT WAY OF MAKING MUTTON STEAKS

EXCELLENT GOOD COLLOPS

BLACK PUDDINGS

TO MAKE PITH PUDDINGS

RED-HERRINGS BROYLED

AN OAT-MEAL-PUDDING

TO MAKE PEAR-PUDDINGS

TO MAKE CALL-PUDDINGS

A BARLEY PUDDING

A PIPPIN-PUDDING

TO MAKE A BAKED OATMEAL-PUDDING

A PLAIN QUAKING-PUDDING

A GOOD QUAKING BAG-PUDDING

ANOTHER BAKED PUDDING

TO MAKE BLACK PUDDINGS

TO PRESERVE PIPPINS IN JELLY, EITHER IN QUARTERS, OR IN SLICES

MY LADY DIANA PORTER’S SCOTCH COLLOPS

A FRICACEE OF VEAL

A TANSY

TO STEW OYSTERS

TO DRESS LAMPREY’S

TO DRESS STOCK FISH, SOMEWHAT DIFFERINGLY FROM THE WAY OF HOLLAND

BUTTERED WHITINGS WITH EGGS

TO DRESS POOR-JOHN AND BUCKORN

THE WAY OF DRESSING STOCK-FISH IN HOLLAND

ANOTHER WAY TO DRESS STOCK-FISH

TO DRESS PARSNEPS

CREAM WITH RICE

GREWEL OF OAT-MEAL AND RICE

SAUCE FOR A CARP OR PIKE. TO BUTTER PEASE

A HERRING-PYE

A SYLLABUB

BUTTER AND OIL TO FRY FISH

TO PREPARE SHRIMPS FOR DRESSING

TOSTS OF VEAL

TO MAKE MUSTARD

TO MAKE A WHITE-POT

FOR ROSTING OF MEAT

TO STEW A RUMP OF BEEF

TO STEW A RUMP OF BEEF

PICKLED CHAMPIGNONS

TO STEW WARDENS OR PEARS

TO STEW APPLES

PORTUGUEZ EGGS

TO BOIL EGGS

TO MAKE CLEAR GELLY OF BRAN

TO BAKE VENISON

TO BAKE VENISON TO KEEP

ABOUT MAKING OF BRAWN

SALLET OF COLD CAPON ROSTED

MUTTON BAKED LIKE VENISON, SOAKING EITHER IN THEIR BLOOD

TO MAKE AN EXCELLENT HARE-PYE

TO BAKE BEEF

TO BAKE PIDGEONS, (WHICH ARE THUS EXCELLENT, AND WILL KEEP A QUARTER OF A YEAR) OR TEALS, OR WILD-DUCKS

GREEN-GEESE-PYE

TO BOIL BEEF OR VENISON TENDER AND SAVOURY

TO BAKE WILDE-DUCKS OR TEALS

TO SEASON HUMBLE-PYES: AND TO ROST WILDE-DUCKS

TO SOUCE TURKEYS

AN EXCELLENT MEAT OF GOOSE OR TURKEY

TO PICKLE AN OLD FAT GOOSE

ABOUT ORDERING BACON FOR GAMBONS, AND TO KEEP

TO MAKE A TANSEY

ANOTHER WAY

TO MAKE CHEESE-CAKES

SHORT AND CRISP CRUST FOR TARTS AND PYES

TO MAKE A CAKE

ANOTHER CAKE

TO MAKE A PLUMB-CAKE

TO MAKE AN EXCELLENT CAKE

TO MAKE BISKET

TO MAKE A CARAWAY-CAKE

ANOTHER VERY GOOD CAKE

EXCELLENT SMALL CAKES

MY LORD OF DENBIGH’S ALMOND MARCH-PANE

TO MAKE SLIPP COAT CHEESE

TO MAKE SLIPP-COAT-CHEESE

SLIPP-COAT CHEESE

TO MAKE A SCALDED CHEESE

THE CREAM-COURDS

SAVOURY TOSTED OR MELTED CHEESE

TO FEED CHICKEN

TO FEED POULTRY

ANOTHER WAY OF FEEDING CHICKEN

TO FATTEN YOUNG CHICKENS IN A WONDERFULL DEGREE

TO FEED CHICKEN

ANOTHER EXCELLENT WAY TO FATTEN CHICKEN

AN EXCELLENT WAY TO CRAM CHICKEN

TO FEED PARTRIDGES THAT YOU HAVE TAKEN WILDE

TO MAKE PUFFS

APPLES IN GELLY

SYRUP OF PIPPINS

GELLY OF PIPPINS OR JOHN-APPLES

PRESERVED WARDENS

SWEET MEAT OF APPLES

A FLOMERY-CAUDLE

PLEASANT CORDIAL TABLETS, WHICH ARE VERY COMFORTING, AND STRENGTHEN NATURE MUCH

TO MAKE HARTS-HORN GELLY

HARTS-HORN GELLY

TO MAKE HARTS-HORN GELLY

ANOTHER WAY TO MAKE HARTS-HORN-GELLY

MARMULATE OF PIPPINS

GELLY OF QUINCES

PRESERVED QUINCE WITH GELLY

TO MAKE FINE WHITE GELLY OF QUINCES

WHITE MARMULATE, THE QUEENS WAY

MY LADY OF BATH’S WAY

PASTE OF QUINCES

PASTE OF QUINCES WITH VERY LITTLE SUGAR

ANOTHER PASTE OF QUINCES

A SMOOTHENING QUIDDANY OR GELLY OF THE CORES OF QUINCES

MARMULATE OF CHERRIES

MARMULATE OF CHERRIES WITH JUYCE OF RASPES AND CURRANTS

TO MAKE AN EXCELLENT SYRUP OF APPLES

SWEET-MEATS OF MY LADY WINDEBANKS

GELLY OF RED CURRANTS

GELLY OF CURRANTS, WITH THE FRUIT WHOLE IN IT

MARMULATE OF RED CURRANTS

SUCKET OF MALLOW STALKS

CONSERVE OF RED ROSES

ANOTHER CONSERVE OF ROSES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Sandra Raphael for her expert advice on plants and her affectionate knowledge of apples; Ian McLellan for his painstaking historical research and his stalwart assistance. We would also like to tender our warm thanks to Research and Innovations at the University of Warwick who have been as supportive of this as they have of all our other projects. Two friends offered us early support: Faith Matthews provided companionship in the interpretation of early modern recipes and Liz Cameron (who in the ideal world would have had time to collaborate with us) gave us valued encouragement. Tom Jaine, of Prospect Books, has helped and encouraged us in every way.

This book began, more than a decade ago, as a proposed collaboration with the late Elizabeth David and progressed some way at that time. Thanks are due to the late Alan Davidson for his kind attempts to assist with the recovery of the original version, and for his and Caroline Davidson’s subsequent guidance of this new edition towards its ideal publisher.

It seems inevitable and fitting that our minority share in this book as its editors should be dedicated to Mrs David’s memory.

Jane Stevenson Peter Davidson S. Joseph of Copertino, 1996

INTRODUCTION

THE LIVES OF SIR KENELM DIGBY AND VENETIA DIGBY, AS WRITTEN BY JOHN AUBREY†

Sir Kenelm Digby, knight: he was borne at (Gotehurst, Bucks) on the eleventh of June: see Ben: Johnson, 2nd volumne:—

‘Witnesse they actions done at Scanderoon

Upon thy birthday, the eleaventh of June.’

[Memorandum:—in the first impression in 8vo it is thus; but in the folio ’tis my, instead of thy.]

Mr. Elias Ashmole assures me, from two or three nativities by Dr. (Richard) Nepier, that Ben: Johnson was mistaken and did it for the ryme-sake.—In Dr. Napier’s papers of nativities, with Mr. Ashmole, I find:— ‘Sir Kenelme Digby natus July 11, 5h 40´ A.M., 26 Cancer ascending’; and there are two others of Cancer and Leo.

He was the eldest son of Sir Everard Digby, who was accounted the handsomest gentleman in England. Sir Everard sufferd as a traytor in the gunpowder-treason; but king James restored his estate to his son and heire. Mr. Francis Potter told me that Sir Everard wrote a booke De Arte Natandi. I have a Latin booke of his writing in 8vo:—Everardi Dygbei De duplici methodo libri duo, in dialogues ‘inter Aristotelicum et Ramistam,’ in 8vo: the title page is torne out.—His second son was Sir John Digby, as valiant a gentleman and as good a swordman as was in England, who dyed (or was killed) in the king’s cause at Bridgewater, about 1644.

It happened in 1647 that a grave was opened next to Sir John Digby’s (who was buried in summer time, it seemes), and the flowers on his coffin were found fresh, as I heard Mr. Harcourt (that was executed) attest that very yeare. Sir John died a batchelour.

Sir Kenelme Digby was held to be the most accomplished cavalier of his time. He went to Glocester hall in Oxon, anno [1618] (vide A. Wood’s Antiq. Oxon.).The learned Mr. Thomas Allen (then of that house) was wont to say that he was the Mirandula of his age. He did not weare a gowne there, as I have heard my cosen Whitney say.

There was a great friendship between him and Mr. Thomas Allen; whether he was his scholar I know not. Mr. Allen was one of the learnedest men of this nation in his time, and a great collector of good bookes, which collection Sir Kenelme bought (Mr. Allen enjoyeing the use of them for his life) to give to the Bodlean Library, after Mr. Allen’s decease, where they now are.

He was a great traveller, and understood 10 or 12 languages. He was not only master of a good and gracefull judicious stile, but he also wrote a delicate hand, both fasthand and Roman. I have seen lettres of his writing to the father of this earle of Pembroke, who much respected him.

He was such a goodly handsome person, gigantique and great voice, and had so gracefull elocution and noble addresse, etc., that had he been drop’t out of the clowdes in any part of the world, he would have made himselfe respected. He was envoyé from Henrietta Maria (then Queen-mother) to Pope [Innocent X] where at first he was mightily admired; but after some time he grew high, and hectored with his holinesse, and gave him the lye. The pope sayd he was mad. But the Jesuites spake spitefully, and sayd ’twas true, but then he must not stay there above six weekes.

He was well versed in all kinds of learning. And he had also this vertue, that no man knew better how to abound, and to be abased, and either was indifferent to him. No man became grandeur better; sometimes again he would live only with a lackey, and horse with a foote-cloath.

He was very generous, and liberall to deserving persons. When Abraham Cowley was but 13 yeares old, he dedicated to him a comedy, called Love’s Riddle, and concludes in his epistle—’The Birch that whip’t him then would prove a Bay.’ Sir K. was very kind to him.

When he was at Rome one time, (I thinke he was envoyé from Mary the Queen-mother to Pope [InnocentX]) he contrasted with his holinesse.

Anno … (quaere the countesse of Thanet) much against his mother’s, etc., consent, he maried that celebrated beautie and courtezane, Mrs. Venetia Stanley, whom Richard earle of Dorset kept as his concubine, had children by her, and setled on her an annuity of 500li. per annum; which after Sir K. D. maried was unpayd by the earle; and for which annuity Sir Kenelme sued the earle, after mariage, and recovered it. He would say that a handsome lusty man that was discreet might make a vertuose wife out of a brothell-house. This lady carried herselfe blamelessly, yet (they say) he was jealous of her. She dyed suddenly, and hard-hearted woemen would censure him severely.

After her death, to avoyd envy and scandall, he retired in to Gresham Colledge at London, where he diverted himselfe with his chymistry, and the professors’ good conversation. He wore there a long mourning cloake, a high crowned hatt, his beard unshorne, look’t like a hermite, as signes of sorrowe for his beloved wife, to whose memory he erected a sumptuouse monument, now quite destroyed by the great conflagration. He stayed at the colledge two or 3 yeares.

The faire howses in Holbourne, between King’s street and Southampton street, (which brake-off the continuance of them) were, about 1633, built by Sir Kenelme; where he lived before the civil warres. Since the restauration of Charles II he lived in the last faire house westward in the north portico of Convent garden, where my lord Denzill Hollis lived since. He had a laboratory there. I thinke he dyed in this house—sed quaere.

He was prisoner, 164…, for the king (Charles I) at Winchester-house, where he practised chymistry, and wrote his booke of Bodies and Soule, which he dedicated to his eldest son, Kenelme, who was slaine (as I take it) in the earle of Holland’s riseing.

Anno 1630… Tempore Caroli Imi he received the sacrament in the chapell at Whitehall, and professed the Protestant religion, which gave great scandal to the Roman Catholiques; but afterwards he looked back.

He was a person of very extraordinary strength. I remember one at Shirburne (relating to the earl of Bristoll) protested to us, that as he, being a midling man, being sett in [a] chaire, Sir Kenelme tooke up him, chaire and all, with one arme.

He was of an undaunted courage, yet not apt in the least to give offence. His conversation was both ingeniose and innocent.

Mr. Thomas White, who wrote de Mundo, 1641, and Mr … Hall of Leige, e societate Jesu, were two of his great friends.

As for that great action of his at Scanderoon, see the Turkish Historie. Sir [Edward] Stradling, of Glamorganshire, was then his vice-admirall, at whose house is an excellent picture of his, as he was at that time: by him is drawen an armillary sphaere broken, and undernethe is writt IMP AVID UM FERIENT (Horace). See excellent verses of Ben: Johnson (to whome he was a great patrone) in his 2d volumne. There is in print in French, and also in English (translated by Mr. James Howell), a speech that he made at a philosophicall assembly at Montpelier, 165… Of the sympathetique powder—see it. He made a speech at the beginning of the meeting of the Royall Society Of the vegetation of plants.

He was borne to three thousand pounds per annum. His ancient seat (I thinke) is Gote-herst in Buckinghamshire. He had a fair estate also in Rutlandshire. What by reason of the civil warres, and his generous mind, he contracted great debts, and I know not how (there being a great falling out between him and his then only son, John) he settled his estate upon … Cornwalleys, a subtile sollicitor, and also a member of the House of Commons, who did putt Mr. John Digby to much charge in lawe… quaere what became of it?

Mr. J. D. had a good estate of his owne, and lived handsomely then at what time I went to him two or 3 times in order to get your Oxon. Antiqu.; and he then brought me a great book, as big as the biggest Church Bible that ever I sawe, and the richliest bound, bossed with silver, engraven with scutchions and crest (an ostrich); it was a curious velame. It was the history of the family of the Digbyes, which Sir Kenelme either did, or ordered to be donne. There was inserted all that was to be found any where relating to them, out of records of the Tower, rolles, &c. All ancient church monuments were most exquisitely limmed by some rare artist. He told me that the compileing of it did cost his father a thousand pound. Sir Jo. Fortescue sayd he did beleeve ’twas more. When Mr. John Digby did me the favour to shew me this rare MS., ‘This booke,’ sayd he, ‘is all that I have left me of all the estate that was my father’s!’ He was almost as tall and as big as his father: he had something of the sweetnesse of his mother’s face. He was bred by the Jesuites, and was a good scholar. He dyed at …

Sir John Hoskyns enformes me that Sir Kenelme Digby did translate Petronius Arbiter into English.

VENETI A DIGBY

Venetia Stanley was daughter of Sir … Stanley.

She was a most beautifull desireable creature; and being matura viro was left by her father to live with a tenant and servants at Enston-abbey (his land, or the earl of Derby’s) in Oxfordshire; but as private as that place was, it seemes her beautie could not lye hid. The young eagles had espied her, and she was sanguine and tractable, and of much suavity (which to abuse was greate pittie).

In those dayes Richard, earle of Dorset (eldest son and heire to the Lord Treasurer, vide pedigree), lived in the greatest splendor of any nobleman of England. Among other pleasures that he enjoyed, Venus was not the least. This pretty creature’s fame quickly came to his Lordship’s eares, who made no delay to catch at such an opportunity.

I have now forgott who first brought her to towne, but I have heard my uncle Danvers say (who was her contemporary) that she was so commonly courted, and that by grandees, that ’twas written over her lodging one night in literis uncialibus,

PRAY NOT COME NEER , FOR DAME VENETIA STANLEY LODGETH HERE.

The earle of Dorset, aforesayd, was her greatest gallant, who was extremely enamoured of her, and had one if not more children by her. He setled on her an annuity of 500li. per annum.

Among other young sparkes of that time, Sir Kenelme Digby grew acquainted with her, and fell so much in love with her that he married her, much against the good will of his mother; but he would say that ‘a wise man, and lusty, could make an honest woman out of a brothellhouse.’ Sir Edmund Wyld had her picture (and you may imagine was very familiar with her), which picture is now (vide) at Droitwytch, in Worcestershire, at an inne, where now the towne keepe their meetings. Also at Mr. Rose’s, a jeweller in Henrietta-street in Convent garden, is an excellent piece of hers, drawne after she was newly dead.

She had a most lovely and sweet-turn’d face, delicate darke-browne haire. She had a perfect healthy constitution; strong; good skin; well proportioned; much enclining to a Bona Roba (near altogether). Her face, a short ovall; darke-browne eie-browe, about which much sweetness, as also in the opening of her eie-lids. The colour of her cheekes was just that of the damaske rose, which is neither too hott nor too pale. She was of a just stature, not very tall.

Sir Kenelme had severall pictures of her by Vandyke, &c. [Her picture by Vandyke is now at Abermarleys, in Carmarthenshire, at Mr. Cornwalleys’ sonne’s widowe’s (the lady Cornwalleys’s) howse, who was the daughter and heire of … Jones, of Abermarles.] He had her hands cast in playster, and her feet, and her face. See Ben: Johnson’s 2d volumne, where he hath made her live in poetrey, in his drawing of her both body and mind:—

‘Sitting, and ready to be drawne,

What makes these tiffany, silkes, and lawne,

Embroideries, feathers, fringes, lace,

When every limbe takes like a face!’—&c.

When these verses were made she had three children by Sir Kenelme, who are there mentioned, viz. Kenelme, George, and John.

She dyed in her bed suddenly. Some suspected that she was poysoned. When her head was opened there was found but little braine, which her husband imputed to her drinking of viper-wine; but spitefull woemen would say ’twas a viper-husband who was jealous of her that she would steale a leape. I have heard some say,—e.g. my cosen Elizabeth Falkner,—that after her mariage she redeemed her honour by her strick’t living. Once a yeare the earle of Dorset invited her and Sir Kenelme to dinner, where the earle would behold her with much passion, and only kisse her hand.

Sir Kenelme erected to her memorie a sumptuouse and stately monument at … Fryars (neer Newgate-street) in the east end of the south aisle, where her bodie lyes in a vault of brick-worke, over which are three steps of black marble, on which was a stately altar of black marble with 4 inscriptions in copper gilt affixed to it: upon this altar her bust of copper gilt, all which (unlesse the vault, which was onely opened a little by the fall) is utterly destroyed by the great conflagration. Among the monuments in the booke mentioned in Sir Kenelme Digby’s life, is to be seen a curious draught of this monument, with copies of the severall inscriptions.

About 1676 or 5, as I was walking through Newgatestreet, I sawe Dame Venetia’s bust standing at a stall at the Golden Crosse, a brasier’s shop. I perfectly remembred it, but the fire had gott-off the guilding: but taking notice of it to one that was with me, I could never see it afterwards exposed to the street. They melted it downe. How these curiosities would be quite forgott, did not such idle fellowes as I am putt them downe!

Memorandum:—at Goathurst, in Bucks, is a rare originall picture of Sir Kenelme Digby and his lady Venetia, in one piece, by the hand of Sir Anthony van Dyke. In Ben. Johnson’s 2d volumne is a poeme called ‘Eupheme, left to posteritie, of the noble lady, the ladie Venetia Digby, late wife of Sir Kenelme Digby, knight, a gentleman absolute in all numbers: consisting of these ten pieces, viz. Dedication of her Cradle; Song of her Descent; Picture of her Bodie; Picture of her Mind; Her being chose a Muse; Her faire Offices; Her happy Match; Her hopefull Issue; Her ’AΠOΘEΩΣIΣ or Relation to the Saints; Her Inscription, or Crowne.’

Her picture drawn by Sir Anthony Vandyke hangs in the queene’s drawing-roome, at Windsor- castle, over the chimney.

Venetia Stanley was (first) a miss to Sir Edmund Wyld; who had her picture, which after his death, serjeant Wyld (his executor) had; and since the serjeant’s death hangs now in an entertayning-roome at Droitwich in Worcestershire. The serjeant lived at Droitwich.

A CHRONOLOGY OF THE LIFE OF SIR KENELM DIGBY

1600The future Venetia Digby born: daughter of Sir Edward Stanley of Eynsham Abbey and Lucy Percy, daughter of the 7th Earl of Northumberland. Brought up at Salden, Bucks.1603(11 July) Kenelm Digby born at Gayhurst (Gotehurst), Buckinghamshire, to Sir Everard Digby and Mary, his wife (née Mulsho).1605Gunpowder Plot: Sir Everard implicated.1606(30 January) Sir Everard hanged, drawn and quartered. Sir Kenelm brought up by his mother, who did not remarry.1617To Spain with his uncle Sir John Digby: negotiations for a Spanish bride for Charles I.1618Enters Oxford as commoner.c.1620-23 Meets Venetia. Shortly after, departs for Grand Tour through Europe. Spends two years in Florence, called to Madrid for unsuccessful royal marriage negotiations early in 1623. Venetia in London. Affair with Edward Sackville, later 4th Earl of Dorset: rumours of a child by him. Her name also linked with other men: Sir Edmund Wyld, Richard Sackville, Robert Carr (Earl of Somerset).1623Kenelm back in England: knighted by James VI.1625Secret wedding of Kenelm and Venetia. Charles I marries a French princess, Henrietta Maria.1626Birth of Kenelm, Venetia’s first son by Digby; pregnancy successfully concealed.1627Privateering in the Mediterranean, writes Memoirs.1628Wins famous naval battle at Scanderoon, June 21.1629Becomes Surveyor General of the Navy in London (till 1635), lives mostly in London. Venetia now openly acknowledged as his wife. Four sons were born: Kenelm, John, George, another who died in infancy, and a daughter (never mentioned).1630Conforms to Anglicanism; becomes friendly with Van Dyck.1633May 1: finds Venetia dead in bed, summons Van Dyck to paint a final portrait, commissions Jonson and others to write memorial verses, then retreats into seclusion at Gresham College.1634Commissions a history of the Digby family, an ornate volume said by Aubrey to have cost £1,000 at the lowest estimate; gives 238 MS to the Bodleian Library, Oxford.1635Returns to Catholicism, and goes to Paris, where he becomes a friend of René Descartes.1637Returns to London: engaged in Catholic apologetics.1638Recalled by Henrietta Maria to help raise funds for Charles’s battle against the rebellious Scots (the first Bishops’ War).1641Called before the Long Parliament and removed from Charles’s Council. To France and Holland: kills a man in a duel and flees back to England.1642Civil War begins. Commons orders his imprisonment.1643Released and banished.1644In Paris: becomes Chancellor to Henrietta Maria, who escapes from England in this year.1645In the Vatican, appealing for funds to help Charles: returns to Paris.1646-8Second fund-raising mission to the Pope, also a failure. Eldest son (Kenelm) killed fighting for the king, youngest (George) dies at school in Paris.164930 January: Charles I executed. Sir Kenelm returns to England in May; banished again August 31.1650Brief return to England to recover his estate.1654Visits Cromwell at Whitehall as intermediary between Cromwell and Cardinal Mazarin.1655Returns to Paris: relations with surviving son (John) strained over what John considered Sir Kenelm’s financial mismanagement. More books given to the Bodleian (Oriental manuscripts) and also to Harvard College.1658-60Tours through France, the Low Countries, Germany, Scandinavia.1660May: Restoration of Charles II. Sir Kenelm returns to his house in Covent Garden.1663Royal Society founded. Sir Kenelm sworn in as member of the first Council.1664Temporarily excluded from the court of Charles II.1665To France, seeking a cure for gout and the stone. Returns and dies (of a fever) at Covent Garden, June 11.SIR KENELM DIGBY (1603-1665)

It would be all too easy to begin this introduction with an elegant double equivocation, to the effect that Sir Kenelm Digby is principally remembered for writing a cookery book and for poisoning his wife. Perhaps one could phrase it even more novelistically, saying that a melancholy interest must inevitably attend a book of recipes compiled by a man widely believed to have poisoned his wife.

Unfortunately, neither statement is true. While Digby collected recipes throughout his adult life, he cast very few of them into the form in which they are given in this book. Most of them are simply printed from his own rough notes, without his editorial intervention, in the words of the friend, correspondent or cook from whom he obtained them. He never thought of them as a book or a potential book: they were collected and roughly ordered into the sequence in which we have them after Digby’s death by his assistant, George Hartman.

It seems, furthermore, unlikely that Digby deliberately poisoned the wife whom he was to mourn with such baroque intensity. Inadvertent poisoning would seem to have been a constant risk attending any use of the random pharmacopoeia of the mid- seventeenth century. Digby was specifically accused of poisoning Venetia with a broth of vipers. To put this in context, it is worth noting that the Great Cordial of no less a man than Sir Walter Raleigh (collected by Digby, and printed by his laboratory assistant Hartman in The True Preserver of Health [1689]) included the flesh, hearts and livers of vipers, along with much else, some of it poisonous. But it seems inevitable, given the place which Digby occupied in the imaginations of his contemporaries, that he should be accused of the very Italian, very Catholic crime of poisoning. The reason that such rumours and imaginations clustered about him is to do with English perceptions of foreignness. As a Catholic, as a courtier identified in the public mind with the unpopular Henrietta Maria, as a man who spent much of his life travelling on the Continent and associating with foreign dignitaries (many of whom gave him recipes), Digby was an obvious figure around whom to weave some of the features of the ‘black legend’ of the depravity of the Catholic South.

Virtually all of his biographers have fallen into that trap. John Aubrey in the seventeenth century is not alone in writing about Digby as though he were the sort of baroquely wicked grandee who inhabits the revenge tragedies of John Webster and the overworked imaginations of xenophobic Protestants. To be fair to Aubrey, however, he seems highly aware in his writing of the status of much of his Digbeian material as rumour, hearsay, gossip and no more. It is only to be expected that when Venetia met an early death, contemporaries would say that she had been poisoned. It is hard to overestimate the fortress mentality of Elizabethan England, and the degree to which it ran to paranoia among those with Puritan sympathies in an England ruled by James I or Charles I, with their foreign, Catholic Queens and their heavily continentalized courts. In the early part of the century, England still thought of herself as embattled against southern Europe, especially after the Gunpowder Plot, which claimed the life of Digby’s father. Less than two decades later, James I’s proposal of a Spanish marriage for the Prince of Wales was attended by a revival of the most rabid anti-Spanish fantasies of the Armada year, and mistrust of Catholics within the gates of England grew. Even without this connection, such a man as Digby, an inveterate traveller from his mid-teens onwards and a speaker of many foreign languages (a facility which the English, then as now, tended to distrust), who was also glamorous, was certain to attract ambiguous and scandalous gossip.

A considerable part of the expected appeal of the recipes when first Hartman published them may well have lain in Digby’s celebrity and the fact that that celebrity was close, in the public imagination, to notoriety: Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, actually describes him as ‘very eminent and notorious throughout the whole course of his life’.

Digby’s glamour is unquestionable. He was larger than life both literally and in terms of personality: ‘a man of a very extraordinary person and presence’, as Clarendon rather grudgingly admits; a compulsive and brilliant talker; a successful naval officer (and pirate); a virtuoso and polymath. Contemporaries thought him one of the handsomest men of his time, ‘the Ornament of England’: this is not reflected in surviving portraits, which may suggest that his attractiveness depended principally on vitality and charm.

He also spoke six languages, and earned the respect of many of his most distinguished contemporaries, particularly scientists: his many friends included Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes and Christiaan Huygens. Most of his scientific activity, like much of the experimental work undertaken by his contemporaries, now appears to be without permanent value, but his Discourse Concerning the Vegetation of Plants (1661) identifies correctly the operation of oxygen and carbon dioxide, while failing to comprehend the precise relation between them. Even his most extreme theory, contained in his Discours...Touchant la Guérison des Playes par la Poudre de Sympathie (1658), of the cure of wounds by the application of a ‘sympathetic powder’ to the weapon, may be less absurd than it seems. Although it has served consistently to bring ridicule on Digby’s scientific reputation (even as recently as the dismissive chapters devoted to him in Umberto Eco’s generally reductive novel The Island of the Day Before [1995]), the late Sir Geoffrey Keynes used to defend Digby roundly in this matter. Sir Geoffrey’s argument was that Digby used the device of the sympathetic powder to persuade the surgeons of the midseventeenth century to cease from packing wounds with the range of potentially septic material in general use at the time, and to cause them instead to clean the wound thoroughly and to cover it with a clean dressing. Digby’s own intention and belief in the matter remains obscure. Perhaps what is most worthy of note is that a desire to reduce his scientific standing is common to almost all of his biographers. The chief cause appears to be the disappointment of the historian of science (working with in a discipline which maintains an inflexibly meliorist view of history) with a figure who was too diversely of his own age to fit the progressive simplifications of the twentieth century.

Digby’s popular reputation focuses on his identities as lover, scientist and patron of the arts; but it is worth noting that some of his other activities are of permanent importance. It is barely an exaggeration to suggest that he is responsible for preserving medieval English literature: the 238 manuscripts which Digby presented to the Bodleian Library in 1634 include (among other treasures) the unique copy of what are still sometimes called the ‘Digby plays’, important manuscripts of Chaucer, Langland, Gower, Hoccleve and Lydgate, and the earliest surviving copy of the Chanson de Roland. Digby also gave an important collection of Arabic and Hebrew manuscripts to the Bodleian at the start of the Civil War; and presented forty books to the new American university, Harvard College, in 1655. His enormous collection of printed books mostly ended up in Paris, and what survives of it is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale.

The biography of Digby and his wife Venetia is complex, and complicated by a number of historical factors. Digby himself was the son of Sir Everard Digby, hanged, drawn and quartered in 1606 for his part in the Gunpowder Plot: his political ambitions, and personal life, were inevitably complicated by both his religion and this damage to the reputation of his family. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Digby spent much of his time abroad from very early in his life: he was fourteen when he first went to Spain, and was sent off on a three-year tour of France, Italy and Spain at seventeen by his mother, anxious to separate him from Venetia (during which tour, he claims indirectly, he was pursued by a number of women, including the dowager Queen of France, Marie de Médicis). This internationalism was bound to cause him trouble, personally and politically, in an England which had inherited from the Elizabethan era not merely chauvinism, but fear and distrust of foreigners. Digby’s public success, limited though it was, is a testimony to his personal brilliance.

Venetia’s position as a young woman of high but far from unequivocal birth—herself rumoured to have borne an illegitimate child to Edward Sackville (later fourth Earl of Dorset)—should have debarred her from making a respectable, even distinguished, marriage. What might have, at best, been expected for her is the fate of a court beauty of the previous generation, Anne Vavasour, who bore a child to the Earl of Oxford, but was devotedly loved by the Queen’s Champion, Sir Henry Lee. After the Oxford debacle, Anne moved in with Lee (a batchelor) at Woodstock, and was his acknowledged mistress throughout his long life. However, he did not marry her: when she was found to be pregnant, she was ‘married’ to an obscure London gentleman called Finch, whose name she thereafter bore. Digby, however, not only married his Venetia, to the considerable astonishment of contemporaries, but openly acknowledged her dubious past: according to Aubrey, he was given to asserting that ‘a handsome lusty man that was discreet might make a vertuouse wife out of a brothel-house’. The bravado or defiance which led Digby to commission Van Dyck to paint the portrait of Venetia now in the National Portrait Gallery seems inexplicable to the late twentieth century. The depiction of Venetia with all the allegorical attributes of Prudence, crowned with laurel by hovering cherubim, with personifications of lust and deceit trampled underfoot, seems to draw gratuitous attention to her equivocal reputation.

Practically everything that is known about Venetia and her past derives either from Digby himself or from John Aubrey’s famous Brief Lives, a series of notes and sketches towards short biographies of his contemporaries, compiled in the later part of the seventeenth century and quoted in extenso above. Since Venetia’s story is so essential a part of the Digby legend, it is worth pausing to note that Aubrey had an extremely good source for his account of her. He gives the name of Sir Edmund Wyld as one of her lovers, the father of another Sir Edmund Wyld, Aubrey’s patron and one of his closest friends, with whom he stayed for long periods. We have therefore a very direct source both for the details of her career (which Digby understandably glosses over), for Aubrey’s memorable short biography, and for Digby’s own comments on Venetia’s early life.

Given how influential Aubrey’s account has been on all subsequent writing about the Digbys, it is important to remember the scope and limitations of the Brief Lives: they originated as notes made for the biographical researches of Anthony à Wood, and thus have the authenticity of notes—direct records of speech. They also have the limitations of all orally-collected material: the memories of Aubrey’s informants are vulnerable to retrospective falsification, to the influences of prejudices and rumours.

While the descriptions of Venetia’s appearance has all the weight (and emotion) of first-hand recollection, probably that of the Wylds, it is sensible to be wary of some of the generalisations in the life of Digby himself, which reflect, perhaps, the hostility which was felt towards a representative of the exotic court of Henrietta Maria rather than any simple historical truth.

Aubrey’s description of Venetia moves, without signalling its change of mode, from documentation, the whereabouts of surviving portraits, to first hand transcribed speech, recollection: ‘She had a most lovely and sweet-turn’d face, delicate darkebrowne haire…’. But then Aubrey moves into either rumour or the selective recording of the quasi-devotional fetishism of the baroque-monster Digby: ‘Sir Kenelme had severall pictures of her by Vandyke, &c. He had her hands cast in playster, and her feet, and her face.’