Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

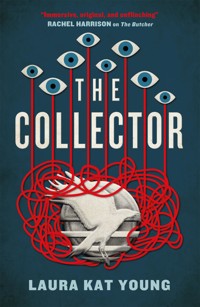

A frightening dystopian horror novel where grief is forbidden and purged from the mind – a nightmarish mix of 1984 and Never Let Me Go. Sorrow is inefficient. It's also inescapable. Lieutenant Dev Singh dutifully spends his days recording the memories of people who, struck with incurable depression, will soon have their minds erased in order to be more productive members of society. At night though, hidden in the dark, Dev remembers and writes in his secret journal the special moments shared with him--the small laugh of a toddler, the stillness of a late afternoon. The first flutter of love. But when the Bureau finds out he's been recounting the memories–and that the depression is in him, too– he's sent to a sanitarium to heal. After all, the Bureau knows what's best for you. A nightmarish descent from sadness to madness, THE COLLECTOR is a dystopian horror novel where grief is forbidden and purged from the mind.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 375

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Part Two

Nine

Part Three

Ten

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By Laura Kat Youngand available from Titan Books

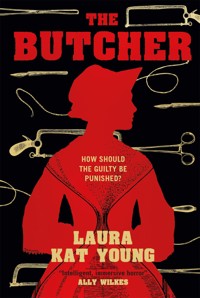

The Butcher

The Collector

Leave Us a Review

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The CollectorPrint edition ISBN: 9781789099058E-book edition ISBN: 9781789099065

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition September 202310 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2023 Laura Kat Young.

All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Bill

PART ONE

ONE

That morning, Dev had breakfasted on sausages. He’d woken ravenous, his salivary glands tightening at the thought of it. He’d forgotten to eat dinner—yes, that was it—and he’d stumbled into the kitchen, groggy and still dreaming. The sausages had tasted salty, comforting. But now, sitting in his car, waiting to go inside Doris McGregor’s home, the meat churned in his belly. He swallowed his hot, thick spit down twice and tilted his head down as if he were looking at something—a map perhaps. His hands. It was only for a moment, and to anyone that had been watching it could’ve been anything. He breathed in, but it was short and rushed and unsatisfying.

Dev pulled the car visor down and looked in the small lighted mirror on its back. His throat felt tight, and he half expected to see his neck bulging, swollen and spilling over the starched fabric of his shirt. He slid his forefinger in between his sticky skin and collar. He tugged at it and then slowly placed his hands on the steering wheel, curling his fingers around the braided leather cover and squeezing until his knuckles turned white. There on his thumb were three tiny marks, little scabs from scraping against something. He dragged a fingertip over the scabs. They were fresh. It was the most curious thing.

He flipped the visor back up and looked out the side window toward Doris’s house. It was like the others on the hidden road: a detached sandstone cottage with a slate roof, and stone pillars flanking the old timber door. But unlike the other cottages on the street, whose windows gleamed and front steps were swept clean, Doris’s curtains stayed drawn. A black wreath hung on her door. There were other telltale signs that she was struck as well—an overflowing garbage can, weeds in the daffodils, a rain-soaked package that had tipped onto its side. They were things that some might easily overlook, but Dev, who had eyes trained to spot such anomalies, noticed. The Bureau had tackled blight during the early years of Mitigation, and now the streets, once rundown and dirty, were tidy; it was nearly impossible to neglect household responsibilities without someone taking note. Doris’s home looked dingy and old compared to the others. But it was to be expected.

Dev straightened his tie, his pocket square, too. Then he adjusted the delicate silver pin on his left lapel. With his thumbs and his forefingers, he reinforced the backing and made sure that the crest of the Collection Unit—a carrion crow landing in front of a setting sun—was upright and secure. When he was satisfied, he breathed in slowly through his nostrils and held the air in his lungs to the count of four. He was supposed to exhale double: four in, eight out—they taught him that in one of the trainings—but when he got to the fifth count, he let the rest of the air out through his mouth quickly, noisily, his lips flapping together in a quick drum.

He grabbed his briefcase, opened the door, and stepped out of the car onto the empty, quiet street. The early morning air was cool. The wind had shifted overnight and now blew up and over the crags, its speed carrying the scent of low tide to the small village where he lived and worked. Dev’s shoes, issued from the Bureau, clicked on the asphalt and then the gravel drive as he approached Doris’s door. He bent to pick up the package on the edge of the stoop—it was the least he could do. The cardboard was soggy and whatever was inside small but heavy. He cradled the box in his arm, and at precisely nine in the morning he rang the bell. A muffled chime announced his presence. A moment passed and then another—perhaps she was not home, and Dev would not have to collect Doris’s donation to the Catalog. He looked at his hands again. Or maybe this was the day, the one he’d kept waiting for, kept dreading, dreaming of. Dev rang the bell a second time. The dog barked. One more ring and he’d have to go in; the collection would turn into a search and rescue. Maybe in the minutes he waited for Doris to come to the door she was swallowing the last of the pills. He tried to steel himself against the idea, but it was of no use. He had already envisioned it, a messy scene played on the backs of his eyes. He wanted to enter then, but he had to give the bell three tries. He turned his good ear toward the door and listened, counting up to twenty in his head. When he reached nineteen, he lifted his hand and at twenty rang the bell for the third and final time. From his pocket, he took a lock opener and opened it to the gauge of the door handle. He thought of Doris, of her photo in her file, and wondered if she wasn’t tucked away somewhere in a closet, a belt or a rope or even bedsheets wrapped tight around her neck.

There was a sudden movement then, a shadow behind the small, frosted window, and the heavy curtains swayed and fell still behind the glass. A dog barked. Three locks clicked, and the door opened. Doris stood there, a good two heads shorter than Dev. She held a small, white dog back with her foot. “Oh,” she said. “It’s you.”

“Yes, yes. Ms. McGregor,” Dev said loudly and put the lock opener back into his pocket. He cleared his throat and still held the small package in his left arm. “Here,” he said. “Careful. It’s a little heavy.”

Dev handed her the package gently. She took it in her old hands but did not look at it. The dog whined and its tail wagged, and Dev bent slightly to hold out his hand to the little pup. “I’m Lt. Singh, from the Collection Unit,” he said as the dog sniffed and then licked Dev’s knuckles. He stood up straight again and took his badge out of his pocket, flipping it open to reveal his photo and credentials. “You should’ve received our correspondence.”

Doris squinted at his identification and then said, “I never got anything.” This may or may not have been true, and Dev saw that the post box was full. “Lt. Singh, huh?”

“That’s correct,” he said, stuffing his badge back in his pocket quickly. He motioned to the post box. “May I?”

“By all means,” Doris said.

Dev pulled out the bundle of mail and flipped through each piece quickly, scanning the upper left corners for the Bureau’s crest. He found it near the middle of the stack, pulled it out, and handed it to Doris. She shifted the package to her other arm to take the piece of mail, and as she did, Dev saw the mourning band tied just above her elbow. Doris must have seen him eyeing it. “I got a right,” she said. “One year from the warning.”

“Of course you do,” Dev said gently. He smiled at her and spoke softly. “I’m sure you are aware, Ms. McGregor, that is today.”

Doris stared at him, her face still and expressionless. She blinked her eyes, glassy but not wet, and she did not reply.

“It’s the twenty-first of June, Ms. McGregor,” Dev said.

She squinted her eyes and looked down at the ground. The dog whined behind her. “Huh. So it seems,” she said. “How do you like that?”

“It’s not uncommon to forget.”

“I didn’t forget. Just didn’t realize what day it was.”

“Yes, well, in any case, it happens often. You’d be surprised.”

Doris’s eyes focused on Dev’s face as if she just noticed he was standing there. “So,” she said. “You’re the Collector. You’ve been out here? Watching me?” She pointed out the door and over his shoulder toward his car.

“Watching you? Oh, no. That’s Surveillance. I simply get the report and do the collections. You won’t see anyone else but myself, and later, the Resetters.”

“Oh, yes. That’s right—I forgot about them.”

The dog barked, a tiny yelp that could have meant anything, and Dev and Doris jumped. “Alright, alright Max,” she said and the dog wagged its tail. “He won’t do a thing,” she said. “Least he hasn’t yet.”

“I like dogs,” Dev said. “Never had one myself, though.”

“They make for good company.”

“Yes, I imagine they would.”

“Well, come on in, I suppose,” she said. “I’ll put some tea on.”

She pulled the door open all the way, and Dev entered, closing the door firmly once he was inside. She bent and put the package on the floor next to the scattered mail and newspapers still in their sleeves leaning up against the wall. Though people could be struck for any reason really, the evidence was always the same: an unkempt property, the stale air of a house sealed shut for months. Dev recognized the thick scent of sadness, and his stomach lurched. He instinctively brought his hand to his nose, but then lowered it. He did not wish to be insulting.

As Dev followed Doris down the hall, he glanced quickly at the art and photographs hanging on the walls. There were people in some. They were smiling, heads leaning in close. Landscapes of various places and handwritten notes hung crookedly in others. The frames sloped to the left or the right, the nails holding them bent and nearly coming out of the cracked plaster. When Dev approached the end of the hall, he saw on his left through a door an unmade bed. Next to it was a nightstand littered with glasses and bottles of medication. Crumpled paper lined the floor next to the bed. He looked away, but he’d already seen it.

Doris turned right and walked through another door into the lounge, closing it as soon as Dev was through. The weather, wet and gray most of the year, found its way easily through the cracks and broken seals of the houses in the village. It was not a poor village— or, rather, no poorer than any other. Doris’s house was somewhat in disrepair both inside and out, but keeping one up took energy, desire, and Dev did not wish to judge the old woman any more than he had to already. In the lounge, large windows faced the street. Two armchairs flanked a fireplace, blackened and well used, and a television in the corner buzzed, the sound turned down low. At first glance, the room looked no different from any of the others he had been in over the last fifteen years. But Dev’s eyes were keen and he was quick to gather evidence someone else might miss. There, on the table next to the armchair closest to the window, was a half-filled jar of jelly beans sitting on top of a neatly arranged stack of glossy magazines. He went to place the rest of Doris’s mail next to them, and as he did he looked at the seat of the chair, indented as if someone had just gotten up and left the room. Though he knew the circumstances from the report, he would have been able to deduce the situation even if it was not his job. Two seats, one empty. Things around them organized as if another person would be right back.

Though Doris had mentioned tea, she did not go into the kitchen. Instead, she lowered herself slowly down into the other chair, the one closest to Dev. Once settled, she patted her lap and the dog jumped up, circling once and then twice before laying down. Dev watched Doris. He made sure to take note of her hands, knobby and buckled, and the single balled-up tissue on the table next to her.

“This shouldn’t take long, though feel free to take as long as you need,” Dev said quietly. He reached into his breast pocket and took out a small black recorder no bigger than his hand. They still did it the old way, on tape, despite the progress that society had seen. There was comfort in pressing the tiny buttons—play, record, rewind—a kind of physical finality to it all. The memories transferred to the tape, and only the tape, invisible on the thin, black material. Whenever he collected a memory, for just a moment, Dev held it all in his hands inside his suit jacket. “I’ve just got to read you the statement from the Bureau and take your donation, and then I’ll be on my way.”

“Would you mind putting the tea on?” Doris asked.

“Oh, yes,” Dev said. “Of course, Ms. McGregor.”

He put the recorder back in his pocket and went into the kitchen. He filled the kettle with water from the faucet and turned it on. Then he opened the middle cupboard, but instead of tea, he found only one box of wheat cereal and a tipped-over jar of instant coffee. He stood the jar upright and closed the door. He opened another cupboard to find mouse droppings—just a few—lining the back edge of the shelf. While he waited for the water to come to a boil, he took a paper towel from underneath the sink, wet it, and wiped down the shelf. He straightened the items on the shelves— bottles of medication, jam jars opened and half-empty, containers of gravy granules, and a Christmas tin of cookies—and then moved to the next. Doris must have heard all the rummaging for she called from the lounge, “The tea is on the counter.”

“Ah, yes,” Dev said. “I’ve got it now.”

The water in the kettle rumbled and bubbled, and when the steam finally rose out of the spout, Dev flipped the switch to the off position. He poured the hot water slowly into a cup with a letter G on it, allowing the teabag to soak and settle to the bottom before topping it off. “Milk or sugar?” he called to Doris.

“No,” she said. “Just a splash from the bottle in the drawer below you.”

Dev pulled open the drawer and found a single unopened bottle of whiskey. He did not recognize the label nor the name, though he himself did not drink much alcohol. She’d been saving this, and for how long was anyone’s guess. He opened it and poured a small amount into the cup. Holding the string between his fingers, he bobbed the teabag up and down in the cup and watched the water darken. Then, for no reason at all, he poured just a tiny bit more of the whiskey into the cup and carried it slowly back into the lounge, careful not to spill on the cushioned linoleum on his way out of the kitchen. He held his right hand underneath the cup just in case, and when he crossed the kitchen threshold, he noticed the balled-up tissue on the small table beside Doris was gone.

Doris had placed a coaster on the table. As Dev bent to place the teacup on it, he saw that the picture on the coaster was of the Bureau’s clocktower. It was a beautiful clocktower—no one could argue otherwise, and Dev, who grew up in the Bureau’s care like the other children of Resets, had spent many days looking at it out of the Home’s window. In fact, if Dev thought hard enough, he could hear the bells that very moment, the deep, reverberating clanging of metal against metal, a reminder that time was indeed passing even if it didn’t seem like it.

Doris leaned over and inspected her teacup, sniffing quietly the steam that rose from it. She did not look at Dev, nor motion for him to sit in the other chair, and so he remained standing. He clasped his hands together in front of his waist and twirled his thumbs softly. Around and around they went, the soft pad of his finger brushing over the nail again and again.

“Shall we get started, Ms. McGregor? They should be here shortly.”

“What do they need my donation for anyway?”

“The correspondence should’ve explained—here—” Dev walked back over to the table where Doris had placed the letter. “May I?”

Doris waved her hand in Dev’s direction. He opened the mail and unfolded the thin letter inside. He cleared his throat and read: “‘Dear Ms. McGregor. You are slated for Reset two weeks from the date of this letter. Should your condition improve within that time, we will notify you via mail. Should your condition remain or worsen, you will be assigned a Collector, who, at 9 a.m. on the date provided, shall come for collection. You may call the number below with any questions. We thank you for your support of the Bureau’s Mitigation program. We look forward to your speedy recovery.’”

Doris sat still for a moment. Then she turned her head upwards toward Dev. “Who reported me?” Doris asked quietly. “Was it Roger on the other side of us?” She leaned her head to the right. “Always nosing around. I never liked him. He got on with Gemma fine, but me… huh,” she said. “That was how it was with her though. Won everyone over in the end.”

“Actually, it was your cleaners,” Dev told her. “You brought in your wife’s clothing two months ago.”

Doris brought her hand to her mouth quickly, and her eyes fell to the floor just beyond her feet. She knitted her brow as if trying to remember doing such a thing. The dog squirmed, but did not move from her lap.

“Yes,” she said. “You’re right. I must’ve forgotten, I…”

But although her mouth remained open, she said no more. Instead, she reached for her tea and brought it to her lips. She held the cup there, not drinking or blowing to cool it. She simply sat, the ceramic edge touching her flesh, a distance in her eyes as though she were looking at something other than the carpet. Dev waited patiently for it to pass as he had been trained to do. Then Doris took a sip. This time the sip was not as small. She took another and another still until the cup was empty. She placed it back onto the coaster gently and looked up at Dev. “I didn’t think they’d say anything. We’d been going there for so long, I just thought…”

Dev waited until he was sure Doris was finished speaking. Then, quietly, he said, “There were other signs, too, Ms. McGregor. You’ve only left the house three times in the last four months. And the weeds—”

“I’ve got arthritis. And who cares if there are weeds?”

“Well, it’s just an indicator, Ms. McGregor. And you’re correct—just one indicator wouldn’t stand on its own, but with the other evidence… it all amounts to it.”

“The cleaners? I just can’t believe it, I really can’t,” she said and shook her head. Her brows creased, her eyes darting, trying to put the evidence together herself. But whether or not she recognized her own behaviors as problematic was of no use; whether the cleaners or the grocers or the neighbor who sat looking out the window all day long had reported her, none of it mattered.

“Not sure if you knew this, Ms. McGregor, but the Bureau added ‘preserving artifacts’ to the list. Not too long ago. Maybe that’s what did it.”

Doris did not say anything at first. Dev stood there, his feet hot in his shoes and the large hand of the clock on the wall in front of him inching toward the hour. “Well,” Doris said eventually, “I see how it might seem. You know, to others who maybe haven’t… but— Lt. Singh, does it seem like it to you? I mean it was just a matter of respect, not like I wasn’t getting on or anything.”

“I’m sure it was,” Dev told her. “Lots of people find themselves in your situation, Ms. McGregor. Quite understandable. However, the cleaners said—and I have to tell you this directly—”

Dev read from the statement he had taken out from his pocket. “‘July 7th. Doris McGregor, of 68 Watson Drive, delivered four garments to V&I Cleaners. As the operator took the garments, Ms. McGregor gripped the sleeve of a shirt and would not let go. Only when the operator reminded her that she was on camera did she release the garment and draw her hand back.’” He folded the statement and put it back into his pocket. “Is this true, Ms. McGregor?”

“What is it to you if it is?”

“Ms. McGregor, it is simply my job to report—”

She sat up straight. The dog jumped down from her lap. Then she rose slowly from her chair, grasping both of the arms with her small hands, pushing herself up into a standing position before bending to pick up the empty teacup and placing it on a tray on the table next to her. “Think I’ll have a little more,” she said. “Care to join me?”

“Of course, Ms. McGregor. Whatever you would like.”

Doris lifted the tray and went into the kitchen. Dev heard the opening and closing of cupboard doors, of drawers, the seal of the refrigerator breaking. While he’d done a cursory scan upon entering the lounge, now that Doris was out of the room he could inspect more closely. He wasn’t required to do so—all the evidence he had needed was in Doris’s file. But he wanted more. There on the walls were photos, framed and aged by the sun. He walked over to look and saw Doris and her wife, Gemma. Their wedding day. Standing beneath one of the giant trees in the forest, walking sticks in hand. Shoulder to shoulder at a café late at night. In some, they were young, but still he recognized Doris. On the mantle was a small collection of shells, driftwood, tiny bits of sea gems. Several jars of layered sand, each section labeled with a date and location directly on the glass. A visual history of their time together. Dev leaned in close to read them, but his eyes suddenly blurred and stung, and when he went to rub them, there was a pull from deep inside his ribs. He shoved his hands into his pockets and balled his trousers’ lining up in his fists to absorb the sweat.

Doris came back into the lounge carrying the tray carefully. On it, Dev saw the open bottle of whiskey, a small container of milk, a dish stacked high with brown sugar cubes. Wedges of lemon fanned out on a plate. Doris put the tray down on the coffee table but did not move to serve. Instead, she returned to her chair and eased herself down, holding onto the arms the same way she did when she arose, her skin above her knuckles thin and white. When she’d settled back against the worn cushion, she clasped her hands together and curled her old fingers around each other. “I couldn’t just leave the clothes on the floor,” she said as the dog jumped back up on her lap. “That would be disrespectful.”

“Hmmm, yes,” Dev said. “Could you not have washed and hung them up yourself? Or perhaps a neighbor or a relative could have helped?”

Dev knew the answer to the questions—of course she couldn’t have. How many days had she spent in bed staring at the clothes? By the time she had thought of dealing with them she must’ve known her actions would draw attention. Or maybe she hadn’t known that. Maybe she had no idea how much time had passed or that she was even still being monitored. Doris’s eyes looked around the floor just beyond her chair, as if she could still see them—the clothes—laying crumpled in a pile she hadn’t the fortitude to tidy up. “They still smelled like her,” she said. “I thought if I got rid of the smell, it’d be easier.”

“Ah, yes,” Dev said softly. “People try all sorts of things, I can assure you. It’s quite understandable, really.”

“I never did pick up the clothes.”

“I know.” Dev spoke softly. “Even if you had, it might not have mattered—there was other evidence, as you know. Besides, there’s no use trying to make sense of it now. May I?” he asked and motioned to the tea there on the table.

“By all means,” Doris said.

Dev fixed himself a cup with two sugars and just a splash of milk. How many times had he been here, sipping tea in someone’s lounge, lording over a person’s grief? Suddenly the back of his neck was hot, and he nearly spit his tea back in the cup. For some reason, Dev’s mind went to his own mother—or rather the idea of her, as he could not actually remember her. After all, he’d been reset when they’d taken him from her. He didn’t remember that, either. He just had an empty feeling where something once was. All the children had it—this feeling—and he had it still. His forehead itched as sweat broke through his skin. If he wiped the sweat, even if it was with his sleeve, Doris would see. It wouldn’t matter in the end—after all, she wouldn’t remember this moment or any other moment tied to her wife. But it mattered to Dev. And as for his faltering, when he tried to understand it, to say to himself he was simply overworked, he couldn’t. He thought quickly again of his own mother and then of the yellow notebook from the Bureau—part of his award package. It was always the same: a sealed envelope, a letter, the notebook. It was stored in his kitchen wall behind a loose piece of paneling. He saw it there wedged in between the old wood frames, years of dirt and dust and silt sitting in the cracks and corners.

“Want a splash?” Doris asked and held the bottle of whiskey out toward Dev.

“No. Thank you. On the clock, and all.”

Dev tilted his glass and saucer toward Doris as a means to show thanks. But moving, even just that little bit, caused a small bead of sweat to drop from his brow into the corner of his eye.

“Ah, yes, of course,” said Doris.

“Unfortunately, Ms. McGregor, we don’t have much time. The Resetters will be here on the hour,” Dev said and took a sip of the hot tea. As he did, he brushed the cuff of his shirt up across the left side of his face. When he brought the teacup back down to the saucer, the porcelain scraped together and drummed under his trembling hands. Too much caffeine in the tea perhaps. “Do you know what you want to donate to the Catalog?”

“Ah, yes. You’re not just here to give me a check-up?”

“Like I said, we’d sent notice, and—”

Doris waved her hand. “Either way,” she said, “glad to be talking to someone, even if it is you. This place’s been empty for a long time.”

Dev gave a small smile with his eyes. “I understand how you feel, Ms. McGregor, and I assure you that as soon as I finish collecting, all of it—the loneliness, the emptiness—it simply won’t be there anymore. We’ll get you right. Now, about the donation?”

“Right. Well I thought I knew what I was going to use. Right up until you knocked on my door. But now,” she shook her head, “now I just, I don’t know, there’s just so much and I—”

“It’s alright, Ms. McGregor. There is no one way— no right way, that is—to do any of this. If I can tell you one thing, it is that everyone lands on something different. No better or worse than the others.”

“Just seems so, well, I don’t know. Small.”

“Well, why don’t you tell me what you were thinking, and I’ll tell you if it’s a good one for the Catalog. I’ll record it just in case, but we can always redo it if you’d like. You have a few extra minutes.”

“I see.” She nodded toward the tea tray on the table and held her cup out to Dev. “Fill me up please?”

Dev placed his own cup, still nearly full, back on the tray. His hands were steady once again. “Of course. Milk and sugar?”

“Just the whiskey.”

Dev uncorked the bottle and brought it over to Doris. He filled her teacup up halfway, tilting the bottle back and pausing as he asked, “More?”

“Yes, just a splash. Maybe two. Gemma—my wife— was always going on and on.”

Dev handed the cup back to her, and she lifted it to her lips. “‘We’ve got to be healthy, Doris,’ that’s what she always said.” Her head was bowed, speaking nearly into the teacup itself. “‘Exercise, Doris. Stop eating so much candy, Doris.’ And for what?” Doris looked up at Dev. “Gemma was fit as could be. Didn’t make any difference, though, did it?”

“Maybe it did, maybe it didn’t. Hard to say. We’ve all got to go sometime,” Dev said. “Haven’t figured out a way otherwise, have they?”

“No,” she said with a small smile. “You know something? You’re okay, Lt. Singh.”

“I am certainly glad you think so, Ms. McGregor,” he said. “Now, what was that memory you wished to donate?” He took the small recorder out from his breast pocket once again and, without looking, pressed the record button down until it clicked.

Doris took a sip and set her teacup on the coaster, covering the face of the clock on the stone tower and hiding the inscription: Damnatio memoriae. “It’s the two of us,” she began. “We’re young—maybe twenty? I’ve forgotten the exact year. Her parents had a cabin on a small lake. Really just a big pond, I suppose. Had cattails and frogs in the summer from what I remember. We took the boat out—I rowed. It was fall, but that day was cold—real winter-like. It was the afternoon. Late in the afternoon, because I remember the sun through the trees low on the horizon. And the water, well, it froze, you see, but just on the top,” Doris said, motioning with her hand as if the air beneath her palm were frozen as well. “And it was so clear that you almost couldn’t tell it was ice but for the oar breaking through. Every time I rowed, it cracked. Crack, splash, crack, splash. Well, we went out to the middle of the water and bobbed for a while until Gemma said she was cold. So I rowed us back. And I stared at the back of her head, at her long hair…”

She did not finish speaking. Dev waited a moment, and then said, “I think it’s a good memory, Ms. McGregor. Just the sort the Catalog needs.”

“But nothing happened. Not really. Don’t you want something bigger? More dramatic?”

“No,” Dev said and pressed the stop button. “This will do just fine. More than fine.” He rewound the tape to the beginning and then held the recorder to his ear and pressed play, making sure that the tape had captured the audio. When he was satisfied, he turned the recorder off and put it in his jacket pocket.

“I heard,” Doris said leaning forward in her chair, her hands cradling the teacup, “that some get to keep theirs. You know, if they have money, that sort of thing. It’s not a lot, but I do have some set aside.”

Dev shook his head, his eyes kind and soft. “That is categorically untrue, Ms. McGregor. I can promise you that. I don’t want you going into this thinking there was some way around it. That’s never good for anyone.”

“Figured it wouldn’t hurt to ask. And you’re sure you can’t let me keep just this one?”

“No,” Dev told her. “I know it seems frightening right now, Ms. McGregor. It is frightening—the unknown, that is. And I know that it’s difficult to understand simply not having certain memories anymore. But you’ll sleep better tonight than you have in ages, and when you wake up, all of this…” He gestured to the walls, to the jar of jelly beans. “All of this will be taken care of for you. You won’t have the slightest idea.”

“You promise that I won’t know?”

“I promise. You’ll have no memory of Gemma. Any common acquaintances will also be erased. You might find yourself forgetful or unable to concentrate, but that will wear off. Some people are hungry after, some are tired. Some feel nothing. Others—” He gestured toward Doris and then the window as if people were just outside the glass. “It’s hard to say.”

“Don’t know why they want them anyway. What good does it do?” she asked. Dev opened his mouth to respond, but she waved him away. “You know,” she said. “It crossed my mind. What some do to try and save— to remember—”

“Whatever you may have heard, Ms. McGregor, are simply rumors. If someone really had been spared, wouldn’t you be able to tell? No, I assure you, there is nothing that can be done.”

“Well,” Doris said. “There is one thing.”

Dev held his breath for just a moment trying to figure if he’d heard her correctly. “Are you referring to a life event?”

“I am. Can’t be worse than this, I imagine.”

“Oh, Ms. McGregor, but it is,” Dev said softly. “Years ago, before Mitigation, I might have even agreed with you. After all, the thought of living with such anguish is terrifying. But this works—just like the other schemes. The Bureau has your best interest in mind.” Dev brought his fingertips to his pin as he said this.

“I suppose,” she said. “And anyway, Gemma—she would’ve, she wouldn’t have wanted me to—”

“I understand, Ms. McGregor,” Dev said. His hand was still on his lapel and this time he felt his heart pulse quickly.

“And you can’t let me just keep the one?”

“I can’t,” Dev said. “I understand how you must feel. Rest assured, nearly all feel like this, and what I mean by that is you are not alone.”

“Is there nothing else to do? What about the Sanitarium?”

“The Sanitarium is, as you know, reserved for essential workers. There just simply isn’t the infrastructure yet to accommodate others that aren’t deemed—deemed—”

“Important?”

“Everyone is important, Ms. McGregor. But to keep the village running smoothly, preference must be given to those with certain responsibilities.”

“So they get to keep their memories?”

“They are treated and reconditioned.”

“Hmpf,” she said. “Doesn’t seem right, does it?”

“Well, the people did vote for it. The mitigation efforts, I mean. Did you vote?”

“Yes. I voted no. Said I’d rather die than lose what I have up here,” she said and tapped the side of her head. “Now look at me. Still alive and about to be reset.”

“If you can try to see it as a new opportunity, a renewal in a way. I’ve found that just shifting a mindset can help immensely.”

The doorbell rang, and the dog jumped down from Doris’s lap. He ran out of the lounge and down the hall to the front door, barking. Doris put her empty teacup on the table beside her and slid a tissue out of her sleeve—the balled-up one that had been there on the table when Dev had first arrived. She brought the tissue to one eye and then the next. What else was she to do? “Well,” she said. “You can let them in on the way out.”

“If you want,” Dev said, “I can stay here with you for the reset.”

Doris looked at Dev with surprise. “You can do that?”

“Yes, Ms. McGregor. This is your collection, so, in a way, you get to make it how you’d like. It’s my job to help you do that.”

“Oh, well, then yes, I think I’d like it if you stayed.”

Dev felt himself smiling and nodding his head, but suddenly none of it was clear. He was staring at Doris, that much he knew, but he didn’t see her, not really. She was saying something else that Dev couldn’t quite catch, her hands moving slowly as she spoke to him. He watched her hands, though, and he thought it was as if she were writing her words in the air. Yes, there was a P and there was an R, and he kept on moving his head up and down. He blinked once, twice, and when he opened his eyelids again he was standing by himself in the lounge. He was staring directly at the bookshelf behind the chair in which Doris had been sitting. For a moment he felt as though he were falling, and he heard the clock chime. It was ten, and the Resetters were due to arrive. Quickly Dev looked around. The shelves themselves were tightly packed—books, pictures, magazines, small vases with long dead flowers poking out from the top. Dev heard voices, muffled and dim, and his eyes fell on the jar of jelly beans. He had a deep and sudden urge to thrust his hand into the jar. He walked over to it, took off the lid, and reached in. His fingers touched the smooth, hard candy, and he heard a knocking at the door. Quickly, he lifted one out of the jar and dropped it into his trouser pocket. He quietly placed the lid back on.

He heard a thump, and a hot panic broke through his skin. He’d let Doris out of his sight; he’d been lost in thought, taking something that wasn’t his to take and now, Doris might be—he ran quickly toward the door, grabbing his briefcase on the way. It knocked against his legs and the doorframe, and he felt the equipment inside banging around. Maybe she’d changed her mind. Maybe she’d hidden a knife underneath a piece of mail on the floor. She’d said Gemma had told her to stay alive no matter what, but Dev knew that most people didn’t think clearly, not this close to a reset. She could have used the knife at her neck or down the inside of her forearm; the blood would come out quick and hot and fast. Dev felt sick at the thought of it, of having to first staunch the bleeding but not before it went everywhere—onto his suit, his trousers as he kneeled on the carpet. But when he turned out of the doorway and into the hall, he saw Doris standing and there at her feet the sodden package Dev had handed her at the door.

“Forgot it was heavy,” Doris said.

“Oh,” Dev said, forcing a smile. “Here, let me help. Is it broken?”

Dev set his briefcase down, thankful he’d hadn’t needed to resuscitate Doris. He bent to pick up the package. As he did a deep shame rose in him—that Doris could’ve done something, that something had impeded his work. He tried to focus.

“Please,” Dev said, holding the package out to Doris. “Use both hands.”

She took it in her hands. The two of them stood there in front of the door, each with their eyes on the package. There was another knock, and one of the Resetters pressed the bell twice in a row.

“Ms. McGregor,” Dev said. “Why don’t you go sit down? I’ll let them in.”

“Oh?” she said. And then, “Alright. Come on, Max.” The little dog circled her feet and pressed his front paws on Doris’ shin. “Come on you old dingo dog, you.”

Dev waited until Doris had gone back into the lounge before unlocking the door. He quickly took his handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his forehead and the back of his neck. He stuffed it back into his pocket and opened the door.

Two Resetters stood before him. They were large men—they were always large men—hulking and wide. They wore white hazard suits emblazoned with a cursive R on the left upper chest. The clear plastic square on their hoods allowed Dev to see their faces, but he didn’t recognize either of them, though he did not often associate with Resetters. He didn’t like their brutishness, the way they’d been selected for their jobs only because of their physique. They were trained to be intimidating, and even though Dev knew there was nothing to fear, he was uneasy. And there were always two of them, their adrenaline and epinephrine surging; it took more than one set of hands to handle the equipment, especially if the struck fought back.

“Hello,” Dev said. “I’m Lt. Singh, Collection Unit. You’re here for Ms. McGregor?” he asked.

The one on Dev’s left looked at the clipboard he held in his hand. “Yep,” he said. “She ready?”

“I believe so,” Dev said. “I’ve just finished her collection.” He watched one Resetter gaze down toward the floor and the piles of mail by Dev’s feet. “It’s alright. I’ve already noted it,” he said.

The Resetters nodded, and Dev stood to the side up against the open door. They entered, and their suits, unwieldy and noisy, brushed up against the walls. Dev pressed his teeth together hard, and his ears filled with the strain. He followed behind them, and when he entered the lounge, he saw that Doris had sat down in the other chair—Gemma’s chair—and had the package sitting in her lap. Dev watched the Resetters flank Doris and take out their equipment. Doris did not watch them. Instead, she watched her own hands open the package. The tape came off easily, and soon she lifted out of the shredded cardboard a small vase. No, not a vase. An urn. She tossed the empty package to the floor and placed the urn on her lap, balancing it so that when she leaned back and dug her bony fingers into the threadbare fabric, it remained upright and still. The dog jumped up and nestled himself in between her thigh and the arm of the chair, whining as she leaned back. Dev watched her hands, how they pushed down into the batting underneath the upholstery, the tips of her nails white from the pressure. By the time she woke up in her bed, the Resetters would have cleaned everything up. All the photos and art and letters—all of it would be gone. She’d wake from her sleep more rested than she could ever remember being, and she’d make her way to the kitchen. There she’d find the tea. She’d make herself a cup and go sit in her chair. As the tea cooled, she’d stare at the indent in the other chair’s seat, the darkened fabric where the cushion had sunk, and think that come next week she’d need to have the upholsterer come around to have a look.

For the second time that week, Dev thought of the extra tapes in the car arranged neatly in a black case he kept in the trunk. They were for emergencies—if the tape split, or the struck got hold of it and smashed it. He could tell the Resetters there had been a malfunction and ask them to wait outside. He’d make something up to say to Doris—the recording was too quiet or the playback full of static. He could record another memory and leave just this one for Doris, hidden somewhere in the hall closet for her to find. Perhaps she would be dusting months or years from now and come upon it. Maybe she might pick it up with bent and worn fingers, turn it over in her palm and hold it to her chest. She’d slip it into her stereo player and hear her own voice, full of love and heartbreak, and know somehow that it was her Gemma, their pond, and the cold autumn’s afternoon.

One of the Resetters fixed the mask to Doris’s mouth and nose, and Dev heard the pop and hiss of the gas.