Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

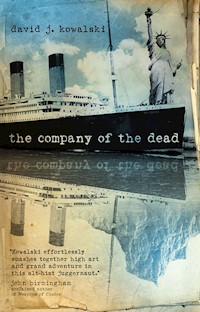

A mysterious man appears aboard the Titanic on its doomed voyage, his mission to save the ship. The result of his efforts is a world where the United States never entered World War I, thus launching the secret history of the 20th Century. April 2012. Joseph Kennedy, relation of John F. Kennedy, lives in an America occupied on the East Coast by the Germans and on the West Coast by the Japanese. He is one of six people who can restore history to its rightful order—even though it will mean his own death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1070

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Overture

I

II

III

The burial of the dead

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

A game of chess I

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

A game of chess II

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

Interlude

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

A game of chess III

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

Prelude

I

II

III

IV

A game of chess IV

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

A game of chess V

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

A game of chess VI

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

The fire sermon

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

Death by water

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

What the thunder said

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Coda

I

Acknowledgements

About the Author

the company of the dead

david j. kowalski

TITAN BOOKS

The Company of the Dead

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686664

E-book ISBN: 9780857686671

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

David J. Kowalski asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

© 2007, 2012 David J. Kowalski

Map copyright © 2007, 2012 Laurie Whiddon, Map Illustrations

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Lisa

OVERTURE

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passed the stages of his age and youth

Entering the whirlpool.

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

I

April 14, 1912North Atlantic

Jonathan Wells stood by the starboard railing, a gaunt figure in a dinner jacket. His coat billowed gently, borne by the ocean liner’s rapid passage. His hair, thick and black, lay damp against his brow. His eyes blinked and watered in the frigid air. The strains of a Strauss waltz rose from somewhere behind him, a low, soft melody that was swiftly surrendered to the night.

I’ve entered uncharted waters, he thought. Hic sunt dracones. Here there be dragons.

The magnitude of his undertaking began to dawn upon him. Tentatively he placed both hands on the ship’s rail. It was one final test of reality, one final test of faith. Cold steel retaliated with teeth of ice. He held his grip till the burn of it receded to numbness.

Two hours earlier he’d found one of the lookouts, alone on the forecastle deck.

“A cold night, isn’t it, Mr Fleet.”

“Aye, sir,” the man had responded with steady deference. “And it’s going to get colder.”

“I believe it’s your watch.”

Fleet nursed a steaming mug of coffee. He nodded between mouthfuls.

Wells withdrew a package from under his coat. “I’ve been asked by Mr Andrews to supply you with these.”

Fleet’s eyes widened at the shipbuilder’s name. Since leaving Southampton four days ago, Thomas Andrews had busied himself about the vessel, attending to minor design flaws and overseeing last-minute repairs. Wells hoped that the delivery of these binoculars would be seen as merely another example of Andrews’ attention to detail.

The crewman turned them over in his hands, studying them in admiration. The binoculars were remarkably compact and extremely light by comparison with the standard issue.

Drop them, Wells thought, and it simply wasn’t meant to be. His pulse was racing now. He realised he was holding his breath. He exhaled slowly. “They’re German,” he said. “The latest design.”

“Bugger me if I can’t see all the way to Dover,” Fleet marvelled. He reddened at the sudden outburst and doffed his cap, apologising.

Wells, concerned with other white cliffs, offered a polite smile. He’d seen this night play itself out a thousand times in his dreams. He fought the urge to tell the lookout everything he knew. “Just keep a sharp watch, Mr Fleet,” he murmured. “Good night.”

He walked away briskly, mute fears clawing at his resolve. He had two hours to kill.

Seeking distraction he toured the Café Parisien and the first-class lounge. He tried to appear relaxed. In the mahogany-panelled smoking room he bought a round of drinks and spoke with a number of its regulars. Even to the last he maintained his one strict, if morbid, rule. His one pessimistic precaution. Captain Smith, Thomas Andrews, Harry Widener, Isidor Straus, Benjamin Guggenheim, John Jacob Astor: he only kept company with the dead. There’d be time enough to forge new acquaintances when the deed was done.

He returned to the boat deck, his agitation mounting. He could feel the bourbon’s warmth slowly leaking from his bones. He glanced towards the ship’s stern and watched as a young couple emerged from the aft stairwell, their burst of laughter cut short by the sudden cold. They huddled together and after a brief exchange returned to the warmth within.

Wells allowed himself a moment’s pride. They’d never know how cold this night could get.

Resuming his vigil he was startled by the brittle clang of the ship’s bell. Three sharp reports issued from the darkness above. The final peal still rang over the waters as he reached for his watch.

Half eleven. Nodding slowly to himself, he replaced the timepiece. His hands shook violently.

“Steady,” he murmured.

He was almost certain that he could feel the ship altering course beneath his feet. Somewhere, orders were being given and received, calloused hands were straining against levers. Fleet must have accomplished his task, for slowly but inexorably their course was shifting.

“Steady...”

He could feel it. The flutter of butterfly wings that would herald a brighter, better world. He looked out to the flat, calm ocean, the moonless night. Beyond the ship’s illumination the dark waters rose up so that he felt as if he and the ship lay at the centre of a vast opaque bowl. Then, at a distance, under the starlight’s dim flicker, he saw it. First, a jagged edge, then two irregular peaks, riding black against the black night sky.

Long minutes passed as the iceberg faded from view. A new melody coursed up from behind him: ragtime. He found himself tapping his foot to the muted rhythm. He turned so that his back now rested against the railing and his face basked in the reflected light of a multitude of windows.

Towards the ship’s bow two crewmen shared a cigarette. They stamped their feet while talking, the cigarette smoke mingling with their fogged exhalations. He approached the entrance to the Grand Staircase, a smile slowly forming on his lips. By the time he reached the crewmen he was laughing openly. They glanced in his direction, nodded respectfully, and returned to their conversation, hushed and conspiratorial in the cathedral night.

Entering the Grand Staircase he peered upwards. The glass dome filtered out the night sky. A chandelier illuminated the room, its own constellation. One of the stewards silently appeared at his side. “Up late, sir?” he said.

“Just taking a turn on the deck. It’s a beautiful night. Almost perfect.”

The steward nodded doubtfully and vanished into the first-class lounge.

Wells descended the stairwell two steps at a time. Down three flights and he was on C deck. The door to the purser’s office was ajar, the elevator unattended. Here, apart from the soft footfall of other passengers and crewmen down other corridors, and the low steady thrum of the engines, all was silent. He walked down the hallway, withdrew a key from his coat pocket and entered his cabin.

The room was cool and dark. He lit the lamp. He crossed to the porthole, placed an outstretched palm against the wall and opened the window, taking in a lungful of cold, crisp air before closing it. Removing his scarf, he drew an ornate chair up to a table that was bare apart from a dog-eared journal. He took a pen from his breast pocket, inspected its nib, and turning to a blank page began to write.

II

April 14, 2012North Atlantic

The night had passed without incident.

Lightholler decided to take advantage of the forenoon watch’s arrival to spend a few moments on deck. His mug of coffee sat on a window ledge near the ship’s wheel, a film of condensation blooming on the thick pane above it. Picking up the mug, he ran a fingernail in lazy swirls on the misted glass. He gazed seawards and spied the bridge’s reflection: his spectral crew superimposed upon the Atlantic dawn. He focused on the image. Men stood gesturing animatedly against a tableau of gauges and switches; Johnson was handing the ship’s wheel over to the first officer. He caught a glimpse of himself and examined the square-jawed, sloe-eyed face that belonged more to a prize fighter than a ship’s officer.

He moved away from the window and stepped out onto the deck. He walked over to the first of the lifeboat davits and glanced back over his shoulder at the squat tower of the bridge. The sun crept weakly across the officers’ promenade. Lightholler let its warmth seep into his bones and looked out to sea. The tapered ribbon of land that had drawn his eyes at first light was now a thickened crust on the horizon. Above it the threat of thin dark cloud mirrored the image below.

He stood for a while, taking occasional sips from his coffee. He didn’t hear the approach of footsteps behind him until he saw a taller shadow engulf his own.

“Almost there, sir,” came a familiar voice. Lightholler turned and had to raise an arm to shield his eyes against the morning sun.

“Not long at all now, Mr Johnson,” he replied to his second officer. “We should make harbour by noon.”

“We’re still riding low in the water, sir.”

“I know,” Lightholler replied carefully.

The two stood in silence for a few moments.

“Aren’t you even curious, sir?” Johnson ventured finally.

“We’re ferrying eight of the world’s most important political figures across the Atlantic, Mr Johnson. Curiosity is a luxury we can hardly afford.”

“Sir, we’re riding low in the water, and I can’t account for it in our cargo manifest. We’re carrying something we don’t know about.”

Lightholler remained silent.

“I’m talking about E deck, sir,” Johnson pressed, his voice low.

“E deck has been sealed off for repairs, Mister Johnson, and we have our orders.”

“I’m an officer of the White Star Line, sir, so why do I feel like a smuggler?”

Lightholler turned again to survey the darkening shore and frowned. “Smugglers usually know what they’re carrying.”

Johnson excused himself and left. Lightholler listened as the footsteps faded away behind him and took another mouthful of coffee. It was cold.

Seabirds could be seen wheeling and hovering over the ship’s prow. As she drew nearer to shore, their numbers swelled, driven by the oncoming storm. The morning’s breeze rose to a brisk wind that raced along the decks and howled through the maze of her superstructure.

The sun was lost within a fold of heavy cloud, turning the ocean blue-black. Waves beat and broke against the ship’s hull in sprays of white froth, the water parting unwillingly before her steady advance. Along the foredeck, men scurried back and forth between the wireless room and the bridge, heads down, scraps of paper clutched to chests or beneath jacket folds, bearing a stream of radio traffic.

Lightholler returned to the darkened wheelhouse and turned his attention to the amassed correspondence that awaited him there: confirmations of arrival times, changes in docking procedures, and offers of congratulations that seemed premature in the face of the approaching squall.

He examined the close-circuit screens, the only anachronism permitted aboard his floating memorial. A light rain from the west drizzled against freshly scrubbed decks, driving most of the passengers indoors. On the poop deck some people stubbornly remained standing by the ship’s rail or seated on benches out of the wind’s path. He cued the audio. The occasional shouts of children merged with the squawks and cries of circling gulls. At the ship’s stern a flag—white star on red—slapped against its pole with every sudden gust.

Passengers sat in the Palm Court drinking tea and coffee, listening to a string quartet play Mozart. In the smoking room they stood in small clusters discussing the recent events in Europe and Asia; the talk mostly of war. The majority, though, would be in their cabins and staterooms, packing away the last of their belongings. The ship sailed on, buffeted by rough wind and water, but in the lounges and dining rooms the only reflection of the turbulence was the gentle swish of liquid in crystal decanters. In fully laden cargo holds, naked light bulbs swung pendulously, marking the ship’s passage in wide arcs.

By the time lunch was announced, the rain had passed and the wind had dropped to a caress. A wall of grey fog greeted passengers who had been summoned on deck by the knock of a steward at the door or the trumpet call of young boys in brass-buttoned jackets. The ship lay swathed in a blanket of cloud, occasional beams of sunlight shining through gaps in the haze like the face of God.

Lightholler sent word to the wireless room, giving instructions to alert the harbourmaster. They would be arriving at dock shortly. He requested that a pilot be standing by to guide the ship up the Hudson to the newly constructed pier on Manhattan’s lower west side. Then, for the first time in days, he allowed himself to relax. The politics and the ice floes lay well behind them. Staring out of the bridge window into the swirling haze, he allowed a smile to form on his face and contemplated his evening ashore.

III

Manhattan lay crouched in the fog.

The ferries to Liberty Island had ceased running at eleven o’clock due to overcrowding. Later estimates suggested that there were twelve thousand people in Battery Park that day, but no one could say how many people swarmed around the terminal and streets surrounding piers nineteen and twenty. From the pebble-strewn beaches of Brooklyn, on past Governors and Ellis islands to the Jersey shore, a flotilla of small boats and yachts rose and fell among the waves. Every now and then a shout would rise from somewhere in the multitude, swell to a roar and fade away in false alarm.

Finally, wreathed in the last of the fog, she appeared on the horizon. At first, in the distance, it appeared as though a small part of the city, its prodigal, was returning home. The great ship grew from the armada’s midst, billows of smoke rising from her funnels and swirling into the clouds above. The small fleet scampered and parted before her prow. The liner’s promenades brimmed with passengers, shouting and waving. All along the boat deck the ship’s officers stood at rigid attention as she steamed past Liberty Island.

A small group of tugboats detached themselves from the piers off Battery Park and slalomed a path through the wall of pleasure crafts to the approaching leviathan.

Lightholler, standing at the ship’s wheel, turned to the first officer and gave the order. Blast after blast emerged from the ship’s foghorn. Johnson, at his station on the forecastle deck, signalled the release of the rockets and one by one they screamed, piercing the dense veil above to explode in flares of blue and white.

New York replied with a series of fireworks that erupted into the grey skies from countless barges. Fire ships in the bay shot jets of steaming water hundreds of feet into the air, turning the heavens into a deluge of rainbows where the sun caught the spray. A cacophony of horns and trumpets bellowed from red-faced men lining the shores and crowding the bobbing boats.

Lightholler and the first officer stood in the wheelhouse watching the spectacle that played out before them.

“Well, sir, we did it,” the first officer said.

“Better late than never, Mr Fordham.” Lightholler smiled.

Giant airships slowly descended from the heavens. German Zeppelins competed with Chinese Skyjunks and Confederate dirigibles, bearing messages of greeting in a host of languages. A century overdue, but heartily welcome, the Titanic nudged her way into New York Harbor.

THE BURIAL OF THE DEAD

I

April 21, 2012New York City, Eastern Shogunate

Captain John Jacob Lightholler woke with a start. Having spent the better part of a fortnight aboard the Titanic, he was pleasantly reassured to find himself in his hotel suite at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Nightmares had plagued him through the restless nights at sea. Never an easy sleeper, he’d attributed them to fatigue, yet still they persisted. By daylight they would slip from his mind, leaving a filmy residue that often darkened his mood. Nightly, he would find himself back aboard the ship, not as its captain but as a fixture of the vessel. A figurehead like those that had adorned the ships of old, pinned to the prow as it ploughed forwards into a shelf of ice that stretched out, vast as a continent, before him.

The last few days were a blur. Speeches, luncheons, keys to the city. He’d been hounded by the media, who delighted in reporting the fact that he was a direct descendant of two of the original Titanic’s most notable voyagers: Charles Lightholler, the ship’s second officer; and John Jacob Astor, the first-class passenger who had gone on to become the Union’s third president. It served to distract the public from the darker aspects of the voyage.

The last-minute inclusion of the Russo-Japanese peace talks aboard ship had proved a disappointment. Under the supervision of the supposedly neutral German diplomats, no satisfactory conclusion had been reached. What had begun as a skirmish between Russian and Japanese soldiers over a border town in Manchuria held the threat of becoming a full-scale war. Newspapers carried accounts of mounting violence in Asia and the eastern provinces of Russia as the Japanese Imperial forces held to their westwards advance.

Both the Russians and the Japanese on board had maintained a veneer of civility, despite the inconclusive nature of the peace talks. Over the past week, under the pretence of social gatherings, Lightholler had been closely questioned by Russian and Japanese envoys alike; both parties displaying a surprising interest in his take on the conference. The Germans, who had up till now remained out of the escalating conflict in Asia, seemed particularly intrigued by his opinions on the subject.

He licked parchment-dry lips. His head throbbed.

He gingerly picked up the phone at his bedside and ordered breakfast and the morning paper. He was told that a stack of messages awaited him at the lobby desk. He replaced the phone and lay back on the bed, gazing dreamily at the ceiling, lulled sleepwards by the faint sounds of the New York morning that drifted through his hotel window.

He was jolted out of his reverie by a knock at the door. He eased himself out of the bed and grabbed a dressing gown that lay draped over his bedside chair. He padded down the short hallway to the door and opened it. Three men stood there, decked out in grey suits. They shared the haggard appearance of journalists chasing an elusive story.

“I’m not doing any interviews today,” he said.

“We’re not reporters, Captain,” the tallest of them said with a ready smile. “We’re here on government business.” His voice, rich in timbre, held the slightest tremor.

Lightholler couldn’t place the accent. He arched an eyebrow, saying, “Which government?”

“We’re from Houston.” The smile faded as the man drew a wallet out of his coat jacket and flashed his identification.

Lightholler peered forwards to examine the card. It identified the man as Joseph Kennedy, an agent of the Confederate Bureau of Intelligence. He scrutinised his visitor.

“Captain, if we could have a few moments of your time.”

“Not today,” Lightholler replied curtly. “You can contact me via the offices of the White Star Line on Monday if you wish.” He began to close the door.

One of the other men wedged his foot into the gap and placed a wide hand on the door’s frame. He was stocky, his red hair cut close to his scalp. He raised his glance leisurely to meet Lightholler’s.

Lightholler sighed. “You’re Confederates. You have no jurisdiction here.”

“We’re well aware of that, Captain. However, we have a delicate matter we need to discuss with you,” Kennedy said. “A matter of some urgency.”

Lightholler wondered at the delicacy involved in having three Confederates barge into his hotel suite at this early hour. Relations between the Union and Confederate states remained cool at best, even though the Second Secession had occurred eighty years ago. That the separation of the southern states hadn’t led to outright civil war that time did little to alleviate the ill feelings that remained between the two neighbours.

Kennedy now appeared more familiar to Lightholler as he swept the years away from his visage. The red-haired man was unknown. The third man, however, had been aboard the Titanic. He’d claimed to be an historian.

Kennedy glanced over his shoulder, bared a toothy grin, and added, “Besides, you don’t want your breakfast to get cold.”

They stood aside to reveal a thin negro dressed in the white livery of the Waldorf’s staff. He was carrying a silver dining tray. “Excuse me, Captain,” he said, smiling. “Eggs Benedict, toast, Virgin Mary and coffee?”

Lightholler stepped back, nodding. “Yes, yes, I suppose so. Thank you.” He motioned the man towards the drawing room.

Kennedy waited for the attendant’s departure before speaking again. “This is Commander David Hardas.” He waved expansively towards the red-haired man, who nodded in acknowledgment. “You’ve met Darren Morgan,” Kennedy added.

Lightholler nodded. “Yes, on my ship.” He tightened the sash around his dressing gown. “So you’re Joseph Kennedy.”

“Yes.”

“The Joseph Kennedy.”

Kennedy smiled.

Lightholler reappraised the situation.

Major Joseph Robard Kennedy, the great-grandson of Joseph Kennedy I; Joseph the Patriarch. This Kennedy had enjoyed a brief but distinguished career in the Second Ranger War, back in the 1990s. Leading the shattered remains of a Confederate division through the San Juan Mountains and across the Rio Grande, he’d cut the supply lines of the invading Mexican army. The subsequent arrival of the German Atlantic fleet in the Gulf of Mexico had led to the hasty withdrawal of Mexican troops.

For the Texans, it was the third war they had fought with the Mexicans in a hundred years. The first was in 1920, when the Mexicans invaded the former United States of America. They were only beaten after a protracted two-year conflict that bled both countries dry. Soon after, America had endured the secession of the Southern States, while Mexico had experienced its last great revolution. The second time the Mexicans went to war with America, in the late 1940s, it was as the newly established Mexican Empire. Having absorbed its neighbours to the south, and following the occupation of Cuba, Mexico had returned its attention to the North. The Texas Rangers, forming the bulwark of the Confederate defence, had narrowly defeated them, thereby lending their name to the conflict.

Barely fifty years later, the Second Ranger War had been another close call for the South. Though it could be argued that it was German intervention that halted the conflict, it was Joseph Robard Kennedy who had been the man of the moment. Riding high on his popularity, Kennedy had run for president of the Confederacy in 1998, but without success. His ingenuous policies were attributed to youth, but it was the stigma of his name that haunted him throughout his fleeting political career. Even then, Lightholler supposed, over thirty years after the event, Southerners recalled the blood spilled at Dealey Plaza.

There had been little news about Joseph Kennedy since his departure from politics. Now, it appeared, he was working with Confederate intelligence. A curious form of backsliding to say the least. The easy grin that had adorned the television broadcasts of the time was barely altered by the passage of time. He still looked like he was in his early forties, at most.

“Just what is it you want, Mr Kennedy?” Lightholler asked.

Hardas coughed quietly and reached into his coat pocket. Lightholler stepped back abruptly.

Kennedy let loose a good-natured laugh. “Captain, please, it’s not like that.” He nodded towards Hardas. “Here. This might help clear things up.”

Hardas drew a slender cream envelope from his pocket and handed it to Lightholler. The thick red wax bore the seal of King Edward IX. Lightholler slit the envelope with a thumbnail. The letter within was brief and to the point. He shook his head slowly. Without looking up he turned and made his way back down the short corridor. His visitors followed him into the drawing room.

Hardas walked over to a window and rested a hand on the sill. He whistled softly to himself as his gaze took in the room’s opulence. “Hell, Major,” he said, “I think I might just have to sign up with White Star.”

Kennedy gave him a half-smile, then turned to Lightholler. “Captain, I take it the letter’s contents are clear to you?”

“They’re clear alright, Major. They just don’t make any sense.”

Lightholler dragged a chair over to the dining table. Absently, he waved the others to find seats. They took up positions on the various plush chairs that lined the room.

The letter was dated April 19, written soon after his arrival in New York. The message was terse, the orders precise. He was instructed to offer the CBI his services until further notice. He folded the document carefully and placed it in one of his pockets.

“There must be some mistake.”

“Why is that, Captain?” Kennedy enquired.

“Because I resigned my commission in the Royal Navy prior to leaving Southampton. I’m a civilian. These orders are from the War Ministry.”

“If I’m not mistaken, they’re from the King himself,” Kennedy replied.

Lightholler swore softly to himself. He’d seen it before. Associates who’d been demobbed, then shifted from military to civilian posts, usually high-profile occupations. Within a few months their names would turn up in the local papers, brief obituaries marking their passing. It was a recognised variation in recruitment for intelligence work. American officers, both Union and Confederate, called it “sheep-dipping”. But if that was the case here, why did London want him to work directly with the Confederacy rather than MI5? And why hadn’t London informed him directly, instead of using agents from a nation that was at best, the ally of an ally.

“Your director must be well connected,” Lightholler observed carefully.

Kennedy grinned wolfishly. “Let’s just say that some people owe me a favour or two.”

A scowl swept Morgan’s features. Hardas remained impassive.

Lightholler’s initial shock was fading to be replaced by anger. “Mind if I smoke?” he asked.

“Your room, your lungs,” Kennedy said, smiling. He glanced at Hardas. “I’m used to it.”

Lightholler retrieved a packet of Silk Cut from the window sill.

Hardas rose from his seat and removed a butane lighter from his pocket. He lit Lightholler’s cigarette. “Mind if I join you, Captain?” He lit one of his own and returned to his chair, where he sat hunched forwards, his cigarette cupped in both hands. He smoked rapidly.

Navy, Lightholler thought, with too many years on deck. Hardas’s hair was cut short, little more than a red tinge on his broad scalp. A scar, barely visible, ran from his hairline across the right temple.

Morgan was eyeing the breakfast. Lightholler took another drag of his cigarette. Of the three, the historian looked the worse for wear. His face was pallid, accentuating the bags under his eyes. His forehead gleamed with a thin layer of drying perspiration, the kind that accompanied sleepless nights rather than any exertion.

“You make an unusual group,” Lightholler said finally. He tapped the ash from his cigarette. “I’m surprised you were allowed past the hotel foyer. In fact, considering the recent events in Russia, I’m surprised you were allowed across the Mason-Dixon Line at all.”

“Well, Captain, these are strange times. And as I said earlier, people owe me favours.”

“So what do you want from me?”

Kennedy turned to Hardas with a gesture. Hardas lifted himself from his seat with a grunt. He mashed his cigarette into an adjacent ashtray, then pulled a small rectangular object from one of his coat pockets.

Lightholler gave Kennedy a puzzled look.

Kennedy was examining his fingernails.

The object in Hardas’s hand emitted a low whine. He held it before him, sweeping it in broad strokes from side to side as he walked the extent of the room. Kennedy started whistling tunelessly through his teeth.

“We’re clear, Major,” Hardas said, returning to his seat.

Kennedy’s whistle faded away.

“Just a formality?” Lightholler asked. It seemed a little late in the conversation to be checking for surveillance devices.

“A precaution,” Kennedy replied. “We need to talk to you about the Titanic.”

“I thought I made it clear that I’m not doing any more interviews.” Lightholler forced his expression to appear amiable, keeping it light.

“Not your Titanic,” said Kennedy. “I’m talking about the original ship.”

This was becoming ludicrous, Lightholler thought. Confederate security agents in his hotel room, with a letter of authority from the palace demanding his assistance, here to discuss a matter that was the focus of every magazine and news programme across the planet.

He forced a laugh. “Surely you didn’t cross half the continent to listen to stories about the original ship.”

“No, Captain.” Morgan spoke up. “We crossed half the continent to tell you one.”

Lightholler let his gaze fall on each of the men in turn. “Must be one hell of a story.”

“It has its moments.” Kennedy rose out of his chair. He straightened his jacket. “But this isn’t the place to discuss it.”

“Where did you have in mind?” Lightholler took a bite from a slice of toast.

“Dallas suits our purpose.”

He almost choked. “Texas?”

“You have three days. I’ve arranged a flight for Tuesday.”

“That’s impossible,” Lightholler spluttered. “The Titanic is due to sail this Friday, after the Berlin peace talks have concluded.”

“She’ll sail without you,” Kennedy said. “You’ll have plenty of opportunities to return to the ship later.”

Lightholler stood quickly and walked over to Kennedy. “I’m going to contact my embassy, Major. Perhaps I should have a chat with the local authorities too. They might be interested to hear about your little invitation, not to mention your presence here in the Union.”

“That wouldn’t be very wise, Captain. I’d hate to think of the complications that might cause you.” There didn’t seem to be any threat in Kennedy’s voice. If anything there was a touch of sadness. “You have three days,” he repeated. “Contact your superiors at the White Star Line. Get in touch with the Foreign Office in London if you need to confirm the letter’s authenticity, but be discreet.”

Lightholler felt light-headed. It was all happening too fast.

“Meet me here, Tuesday, two o’clock,” Kennedy concluded, handing Lightholler a card.

Lightholler examined the piece of paper. The words “Lone Star Cafe” were pencilled in broad strokes. The address was in Osakatown, in the East Village.

Three days would be more than enough time to extricate himself from this predicament. He said, “I’ll consider it.”

“Come alone. Don’t worry about your belongings—they’ll be taken care of.”

“I’ll consider it.”

Hardas and Morgan rose from their seats. They moved towards the hallway entrance.

Kennedy nodded at the letter in Lightholler’s pocket. “I’m afraid it’s out of your hands, Captain.” He pressed his lips together in a tight smile. “We’ll see ourselves out.”

In the hour that followed, Lightholler checked his hotel suite door twice, making sure it was locked. He paced the floor and slammed his fist into the wall of his bedroom, leaving a faint impression in the plaster. He smoked seven cigarettes, lighting one from the other.

He stood in the bathroom before the full-length mirror. He ran the palm of his aching hand over a stubbled chin, teeth clenched. Snatches of the conversation repeated themselves in his mind, the words playing over and over till their meaning was lost.

White noise.

You have three days...

He went over to the shower, a glass-walled cubicle that took up nearly half the room. He ran the water cold at first, sending a shock through his frame, then slowly increased the heat. He looked up at the showerhead and screwed his eyes up tightly, letting the furious stream blast into his face.

He stood there, eyes closed, hands braced against the wall, and pictured the great ship as his great-grandfather had described her, all those years ago.

II

April 15, 1912RMS Titanic, North Atlantic

Wells sprawled over the cabin’s table, one hand outstretched on the journal, the other cradling his head. A tumbler lay on its side. An amber slick traced a pathway across the creased paper. At the table’s edge an empty bottle rolled precariously.

He woke to an explosion of sound at the door. Muffled shouts came from without. Unsteadily he rose and eyed the clock on the mantle: three o’clock, and still dark outside.

He leaned heavily against the door as he opened it. Crawford, his steward, framed the doorway. Behind him, Wells could see passengers in various states of undress moving hurriedly back and forth.

“I’m terribly sorry to disturb you at this time, Mr Wells,” the steward said.

Wells swayed at the cabin’s entrance, rubbing his eyes. “What’s happening?” he slurred.

Crawford glanced nervously over his shoulder. “We are experiencing a small difficulty. No need for alarm, sir; however, Captain Smith has asked that all passengers make their way to the boat deck till matters are sorted out.”

“You’re kidding me.”

“I’m afraid not, sir.” His smile was strained and unconvincing.

Wells noticed the thin line of perspiration moistening the elderly man’s moustache. Slowly his back straightened, his mind cleared. Despite the noise of scurrying passengers, he realised that the ship’s engines had fallen silent.

The air was pierced by a sudden shriek that filled their ears.

“They’re venting the steam,” Wells said. “We’re not moving. Why have they stopped the ship?”

“I’m not sure, sir,” Crawford replied hurriedly. “However, if you would please make your way topside, I’m certain we will be under way again in no time.”

The ship was not moving. Wells had an unpleasant sensation of déjà vu. “Crawford, have we struck something?” His voice was almost lost in the din.

A look of surprise flickered over the steward’s face. He lowered his eyes. “I believe we may have grazed an iceberg, Mr Wells.”

“Grazed?”

“That is my understanding.”

“Motherfucker,” Wells hissed to himself.

Crawford’s face registered shock. Only his unfamiliarity with the term seemed to hold him in place. Wells realised another slip like that would not be tolerated. “How long do we have?” he asked.

“I’m sure I don’t know what you mean, sir.” Crawford’s curt reply spoke of more than just dismay. He departed quickly and silently.

Wells stared for a moment at the open doorway. Turning back into the cabin, he glanced at the journal and swallowed a harsh laugh. He went to the cabinet and removed a fresh bottle. He righted the fallen tumbler, placed it on the table’s edge and poured himself a measure.

Staring at the glass, he noticed a slight tilt in the fluid level.

“I’ll be damned...”

He folded the journal under his arm. Taking his scarf and coat from where they lay on the bed, he strode out into the vacant hallway.

I have to assess the damage, he thought. Just keep calm. Yet it beggared belief. He’d stood on the boat deck at eleven-forty, and watched the iceberg slip past with hundreds of feet to spare. There’d been no collision. Surely they couldn’t have struck a different iceberg, later in the night? The possibility was outrageous.

He had to speak to Andrews, Captain Smith, Officer Lightholler... someone. But first he had to deal with the journal. It was his only link to the world he’d known. The thought of losing it was unbearable. He had to place it where he could reclaim it later, when he had used his knowledge of the ship to save it.

He entered the C deck stairwell to find a small queue forming outside the purser’s office: mainly servants and maids along with the occasional bewildered first-class passenger. Glancing at his watch he saw that it was ten past three.

A woman’s voice, sharp and penetrating, issued from the office. Wells tapped his foot, muttering to himself, “No good, this is no good.” He shouldered past the crowd and moved towards the entrance, ignoring the disgruntled mutterings behind him.

Within, a middle-aged woman in a nightdress leaned over the purser’s desk. Behind the glass the purser’s face was a glazed veneer of sweat.

“Madam, may I be of assistance?” Wells interrupted.

“This... fellow,” she indicated the purser with long, outstretched fingers, “cannot find my jewellery box.”

The purser began to splutter a response. Wells raised a hand to stop him. “Why on Earth would you want your jewellery box at this hour, madam?” he asked gently.

“Because I am not leaving this ship without it.” She spat the words out with venom.

“No one is leaving the ship.”

“Have you been on deck, sir? They are uncovering the lifeboats as we speak.”

“I’m sure it’s just a precaution, madam,” he replied, echoing the steward’s lie.

The woman paused to examine Wells’ calm mask. He held it together. They might still be saved. All of them.

She turned to toss the purser a final scowl and swept out of the small office.

“Thank you, sir. It’s been like that ever since they started waking the passengers.”

Wells nodded absently. He reached under his jacket and withdrew the crumpled journal. “I represent Mr Ismay. This contains all my notes, ship modifications, everything. It must be secured in the ship’s safe. I must find Andrews and I don’t want the damn thing lost in all the confusion. Is that clear?”

“Crystal, sir,” the purser replied, accepting the book carefully.

Relieved, Wells slipped from the room.

III

Wells pushed past the growing queue. The banshee’s cry of venting steam struck his ears again, louder now, rattling the teeth in his jaw.

It was less crowded on A deck. A few people wore dressing gowns. The majority were still in evening wear. Colonel John Jacob Astor stood by his wife, Madeleine, outside the entrance to the first-class lounge. A young couple, clutching each other like honeymooners, were comparing notes with one of the stewards. The man was describing how he’d been woken by an unusual scraping sound at around half past two.

“It sounded like a huge nail being scratched down her side,” he said, demonstrating with an outstretched hand.

Some of the passengers were dismayed at the delay. Others looked excited by the prospect of an adventure at sea. Wells smiled at those who smiled at him, hoping fervently that he, too, would have stories to tell when they arrived in New York.

If they arrived in New York.

He tried to cast the bitter thoughts from his mind as he climbed to the top of the stairs and stepped onto the boat deck. The evening had grown colder. Earlier, the deck had been desolate and silent as he watched the iceberg drift by. Now, crowds thronged the open promenades. Children clung sleepily to their mothers’ coats, or ran about the boat deck laughing, pursued by their nannies. Men in dinner jackets stood quietly in small gatherings, smoking and peering out to sea.

He approached the port-side railing as if in a dream. Noise swelled up from below as the passengers lined the walkways and gazed up at the lifeboats. He could hear music: Wallace Hartley had assembled his fellow musicians by the gymnasium and they were playing “Oh, You Beautiful Doll”.

He could sense the slight list of the floorboards beneath his feet and it was almost too much for him. He’d wanted to prevent all of this; had come aboard specifically to stop this from taking place. He felt dizzy, nauseated. A tide of fear rose in him.

He’d seen the iceberg with his own eyes. What could possibly have gone wrong?

He peered out over the still waters. They were drifting in a field of ice. He stared at the small icebergs, the growlers, the field ice that dotted the flat, coal-dark sea. To the north and west an unbroken field stretched out to the horizon. He tore himself away from the railing and worked his way along the promenade towards the second-class stairs.

“Jonathan,” a voice cried out. “Thank God it’s you.”

He turned and saw her standing a small distance from the crowd. A slender woman with an oval face. A white shawl was wrapped tightly around her head and neck; fugitive wisps of auburn hair trailed her lined brow.

“Virginia, what are you doing here? Why aren’t you on one of the lifeboats?”

He’d met her in the Café Parisien on their first night aboard. Unsure of her place on the list of the damned, he’d pursued a cautiously detached flirtation.

“I was about to climb into one when I saw you rush past.”

He grabbed her by the shoulders. “Are you insane? Why did you follow me?”

She drew back from him, stunned. “I couldn’t find you earlier this evening. You disappeared straight after dinner.” She made a vain attempt at a smile. “I thought you might have resumed your mysterious little exile.”

“You must get off this ship.”

“What is the urgency? Mr Murdoch told us that everything would be alright.” She stared up into his eyes. “Everything is going to be alright, isn’t it?”

“I don’t know,” he replied. She was trembling with the cold and new fear. “Take this.” He removed his heavy coat and threw it over her quivering shoulders. He turned to leave.

She took a step to follow him. “Jonathan? Won’t you need it? Where are you going?”

His shoulders slackened but he didn’t look back. “Get into one of the boats, Virginia.”

He approached a group of passengers trying to return to their rooms. Two crewmen barred their way.

“Has Mr Andrews been here?” he asked.

“Went below not ten minutes ago, him and the carpenter,” the taller man replied.

“Where were they going?”

“I heard them say something about the boiler rooms,” the smaller one piped up.

“Then I have to join them immediately,” Wells said firmly.

“No one’s allowed below decks.”

“Do you know who I am?”

“I don’t care if you’re Mr Bruce Ismay himself. I have my orders.”

Wells’ voice dropped to a hiss. “And who do you think gave those orders?”

The two men glanced at each other in confusion and parted sheepishly. Wells turned to face the crowd. “You there,” he said, raising his voice. The din subsided for a moment. “All of you, please assemble by the lifeboats. You’ll all be able to return to your cabins shortly.”

The passengers remained there for a moment, muttering and grumbling. They eyed one another with suspicion and slowly thinned out towards the lifeboat davits. The taller of the two crewmen raised a hand to his cap.

Wells passed carefully between them and into the stairwell. Bright light assailed his eyes. He raced to the staircase and descended rapidly, his feet beating a staccato on the wooden stairs. This part of the ship appeared deserted.

He encountered a group of crewmen on the D deck landing. “Andrews,” he gasped. “Where is he? I must find him.”

“Follow me, sir,” a crewman responded.

Glancing over their shoulders, he could see the steerage passengers standing quietly behind a single velvet rope. He stood transfixed by the vision.

“Sir?” the crewman said.

“Sorry. Thank you. Lead the way.”

The crewman winked at one of his fellows and guided Wells down the stairs to E deck. “We can’t go via F on account of all the riff-raff down there. This way then.” He led Wells to Scotland Road—the crew’s nickname for the passageway that ran the Titanic’s length, permitting crew and staff to traverse the ship out of the passengers’ sight.

“Down here, sir.” The crewman pointed to an unmarked iron doorway in the wall. “This will take you through to the engine room. Mr Andrews should be there.” The young man chuckled, “Be glad when you gents have the ship running again.”

Wells let himself through the iron door. It clanged behind him, ringing in his ears. He found himself in darkness. A wave of heat swept over him. Crewmen’s voices wafted up from below. He stamped down a thin metal stair onto a narrow walkway, then wound his way into the depths of the ship, keeping one arm on the banister for guidance. He crossed the metal causeway that led to the first of the boiler rooms.

Andrews was there, hunched in conversation with an older frosty-haired man in a crumpled brown suit. He glanced up at Wells’ approach, rolled up the set of blueprints he had been studying and tucked them under an arm. “What brings you down here, Wells?” he asked. He looked appalling. His brown hair hung in thin damp clumps, his shirt was stained with perspiration and oil.

Wells was now more thankful than ever that he’d made the man’s acquaintance earlier in Belfast. “I came to see you,” he said. “To see if I could help. The steward said we’ve struck an iceberg.”

Andrews sighed heavily. “And so we have. Short of manning the pumps, however, I don’t think there’s much you can do down here.” He turned and said something quietly to the older man, who made a small bow and disappeared down the walkway. “Ship’s carpenter,” he explained, and headed towards the forwards boiler rooms.

Wells dogged his heels.

The elevated walkway was dimly lit by the occasional lantern. Most of the light came from below. He followed Andrews from boiler room to boiler room, glancing down at the piles of black coal, the shadowy black-masked faces of men under-lit by the red stage lights of the furnaces. Their inarticulate shouts merged with the rising shrieks of the boilers. He looked to his guide and thought of other guides and infernos. Recalling that Dante’s vision of Hell ended in a lake of ice made him shudder.

They stopped in the fourth boiler room. Charles Lightholler, the ship’s second officer, stood in the middle of the passageway, his eyes fixed on the scene below. Engineers struggled to repair the frothing mouth of a wound that coursed along the visible length of the bulkhead. Firemen manned the pumps. Inches away from the tumult, sweat-soaked boiler men continued shovelling coal into the furnace’s gaping mouths.

“It’s the same in boiler room five,” Andrews said. “Number one hold, number two hold, boiler room six, the mailroom...” His voice trailed away.

Wells looked into Andrews’ face. “How long until we have matters in hand?”

“Matters in hand? She’s been gutted along the greater part of her length. The lower decks forwards to F deck are awash. The squash court is flooded, and the water is rising too damn fast.”

Wells made a quick calculation in his head. The iceberg had struck the ship on her port side. Historically, the Titanic had been snagged to starboard, receiving a glancing blow along the first three-hundred feet of her hull. The first four compartments and forwards boiler room had been damaged and in less than ten minutes the ship had flooded to fifteen feet.

This time it appeared that more than four-hundred-and-fifty feet of hull had been torn along the port side. The consequences would be the same. It didn’t matter if it was the port or starboard side. It didn’t matter if the tear was an inch wide or a jagged gash. If more than five of the Titanic’s sixteen watertight compartments flooded, the ship could not remain afloat. And according to Andrews’ description, at least seven watertight compartments had been compromised.

She was going to sink. Again.

Wells cast about furiously in his mind. There was one possibility... something he’d read, something that might at least buy them time.

Clouds of steam billowed up from below. The air was moist and thick in their lungs. Lightholler turned to his companions, suppressing a cough.

“Any word from the wireless room, Charles?” Andrews asked.

“None as yet. So far we’ve only been able to raise the Olympic. Everyone else appears to have switched off for the night.”

“What about the Carpathia?” Wells urged. “Or the Californian?”

Lightholler seemed to notice him for the first time. “What are you talking about?”

The Californian was a tramp steamer that had been locked in a field of ice, allegedly in full view of the sinking Titanic. It had been the Carpathia that had rushed to the Titanic’s rescue. Captain Rostron had given the order to ‘go north like hell’. The Carpathia had arrived too late to save the ship, but had taken all seven-hundred-and-five of the survivors on board.

Wells asked again, “Have we heard from the Carpathia? Is she coming?”

“The only ship we have heard from is our sister ship and she is five-hundred miles away. Cape Race is attempting to contact other vessels,” Lightholler replied. He glanced at Andrews. “I had best be returning to the bridge. Is there anything I can tell Captain Smith?”

“I have told him everything,” Andrews said softly.

Lightholler nodded.

Wells cleared his throat. It was worth a shot. “Perhaps if we kept moving?”

“I beg your pardon?” Lightholler said.

“Perhaps if we kept the ship moving. We might take on less water.”

Lightholler stared at him blankly.

Andrews shook his head. “I don’t know, Jonathan,” he said. “I don’t know. It is impossible to say.”

Wells continued hopefully. “Back in New York, we conducted a study on ship collisions. Projections suggested that ships with tears along their bow would ride higher, take on less water, if they kept in motion.”

Lightholler shook his head. “I’m not familiar with that article.”

Wells persisted. “The passengers might find it reassuring as well, if we were under steam.”

He turned to look at Andrews. Suffused in the red reflection of the furnaces, the man’s face shone wetly. Condensed steam—or tears—streamed down his cheeks.

“In the face of the damage we have sustained, I cannot be certain whether it will help or hinder our situation,” Andrews replied.

They all fell silent.

“I shall run it past Captain Smith,” Lightholler offered finally. He gave a brisk nod. “See you up top then,” he said, and he strode back the way they’d come.

Water was coursing through the lower portion of the bulkhead, swirling at the feet of the engineers and boiler men.

“What are you going to do now?” Wells asked Andrews. “I have to remain down here for the moment. There still may be a way we can purchase some time.”

Wells left him in the boiler room.

IV

Scotland Road was empty.

Wells imagined a low tide at its bow end, inexorably working its way up in frigid ripples to swallow them all. He spun around in the empty passage, aimless, and his eyes fell upon an axe cradled within a sealed glass cabinet. Above it a sign read “In case of Emergency, smash glass”. He lashed out with a booted heel. The glass cracked. He kicked again and it shattered, spraying his leg and chest. A shard stung his face. He stood breathing raggedly, staring at the broken cabinet, the axe that hung within.

He leaned back against the wall and slowly sank to the floor. His hands were splayed out on the cold steel floor. Flecks of drying blood peppered his knuckles.

Did I do all that I did just to end up here?

A faint vibration teased his fingertips. He felt it through the heels of his boots. He spread his palms wide, confirming the fact. They were moving again.

He raised himself off the floor uncertainly. “Well, what do you know?” he murmured. He brushed the flakes of broken glass from his coat and trousers. He looked up and down the corridor. Ahead lay the stairs to second class that he had descended. He started up the inclined passageway.

On the D deck stairwell, crewmen stood shouting at a small crowd that had formed behind the flimsy barricade. The steerage passengers were calling back in their native tongues. Other members of the crew were erecting a small metal gate of trellised iron. One of them turned to see Wells on the staircase, surveying the scene. “Back in business?” he shouted.

Wells shrugged and continued up the staircase. On C deck he glanced down the corridor that led to his cabin. Two men had a steward penned up against a wall. He couldn’t hear their words. The steward broke away from their rough embrace and continued walking up the passage, checking the cabins. The men, clad in a blend of dinner wear and nightshirts, observed the steward’s retreat. Dogs, lost in the rain.

Approaching the boat deck, Wells could hear the rising clamour. More crewmen stood at the entrance to the second-class stairs and were arrayed further down the stairs. They blocked the passage of third-class passengers from below and first-class passengers from above. Pandemonium reigned. He broke through the assembly and dashed over to the starboard railing.

Far below he could see a lifeboat in tow near the ship’s stern. Another drifted into view, caught in the froth of the ship’s wake. Its passengers were shouting at the crewmen who stood by the tiller, at the people at the ship’s railing.

The ship was moving slowly. Five, ten knots per hour. He couldn’t be sure.

An officer stood nearby at an empty lifeboat cradle. It was William Murdoch, the ship’s first officer. He was calling out to the crewman in the first lifeboat Wells had seen. Another officer ran up to join him, his uniform in disarray, his hat crushed under one arm.

“Mr Murdoch,” he panted, “what should I do? I was asked to lower the lifeboats not ten minutes ago. Now we are making headway again.”

“Lower your voice, man. Compose yourself.” Murdoch scowled. “Ensure that the lifeboats are ably manned. We can always return, or send another ship to retrieve them.”

The dishevelled officer nodded frantically.

“For the moment, though, keep the remaining lifeboats uncovered.”

Wells made his way towards the stern. He descended the narrow stair to the poop deck. A few of the steerage passengers were already gathered there. He followed their gaze.

The two lifeboats had both been drawn into the ship’s wake. The ropes securing them to the liner hung taut. The tiny craft rolled and swayed in white foam. They could not have been more than one-third full; all of the passengers were women, who sat gripping the gunnels. Each small crash of the lifeboats in the ship’s spume was punctuated by their cries.

The officer appeared at Wells’ side and called out to the crew manning the ropes. Two of them grabbed lengths of chain from piles of twisted cable at their feet. They threw the chains over the straining ropes and wrapped the metal links about their wrists. As one they stepped over the rail and balanced precariously there. They launched themselves from the ship’s stern, sliding down the ropes into the darkness. When it seemed as though they would crash into the small boats, they released the chains and dropped into the seething water. In a tangled flurry of arms and legs they were dragged into the boats.

A cheer rose from the passengers on the poop and upper decks. Wells was surprised to find himself joining in.

Crewmen were working on the secured portion of the ropes at the flagpole’s base, preparing to cast off. Wells stared down at the two small boats. They seemed so fragile in the wake of the mighty liner. In moments they would be released.

His gaze shifted, up past the red flag that hung limply from the flagpole. The ship seemed to rise to the heavens. It stretched out before his tired eyes towards the horizon. Invulnerable. Indestructible. Unsinkable. For the first time he truly understood why the lifeboats had been undermanned. Who could leave this vast city of a ship for the insecurity of the small, frail craft that creaked and swung in the lifeboat davits? Even with everything he knew, the choice seemed unclear.

Should he jump now and risk the cold waters? Try to make his way to one of the boats? He looked down at the water’s surface, trying to judge the distance in the gloom. His head swung crazily back and forth, from the ship to the lifeboats and back again.

Beside him, two passengers rushed the railing. One swung himself over the top and stood there, facing the crowd. He met Wells’ eyes with a brief look of comprehension. A crewman swung a swarthy arm to grab at the passenger’s worn coat sleeve.

There was a sharp twang as both ropes snapped free from their restraints, whistling through the icy air. The passenger’s face tore open in an ugly red weal. Its flayed remnant managed to convey his astonishment before he dropped into the ocean.

There was a groan of dismay from the assembled crowd. Wells backed away from the railing, shaking his head. In the distance he could see the two small boats recede, lanterns swinging from their prows like fireflies courting in the gathering dark.