Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

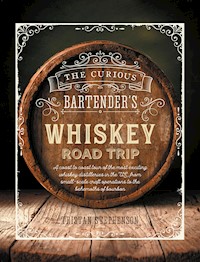

An innovative, captivating tour of the finest whiskies the world has to offer, brought to you by bestselling author and whisky connoisseur Tristan Stephenson. Tristan explores the origins of whisky, from the extraordinary Chinese distillation pioneers well over 2,000 years ago to the discovery of the medicinal 'aqua vitae' (water of life), through to the emergence of what we know as whisky. Explore the magic of malting, the development of flavour and the astonishing barrel-ageing process as you learn about how whisky is made. In the main chapter, Tristan takes us on a journey through 56 distilleries around the world, exploring their remarkable quirks, unique techniques and flavours, featuring all new location photography from the Scottish Highlands to Tennessee. After that, you might choose to make the most of Tristan's bar skills with some inspirational whisky-based cocktails. This fascinating, comprehensive book is sure to appeal to whisky aficionados and novices alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 602

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE CURIOUS

BARTENDER

AN ODYSSEY OF

MALT, BOURBON & RYE

WHISKIES

THE CURIOUS

BARTENDER

AN

ODYSSEY OF

MALT, BOURBON & RYE

WHISKIES

TRISTAN STEPHENSON

WITH PHOTOGRAPHY BY ADDIE CHINN

Designer Geoff Borin

Commissioning Editor Nathan Joyce

Head of Production Patricia Harrington

Art Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Publisher Cindy Richards

Indexer Diana Le Core

First published in 2014 by

Ryland Peters & Small

20–21 Jockey’s Fields

London WC1R 4BW

and

519 Broadway, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10012

www.rylandpeters.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text © Tristan Stephenson 2014

Design and photographs © Ryland Peters & Small 2014

The author’s moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

eISBN: 978 1 84975 907 6

ISBN: 978 1 84975 562 7

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

US Library of Congress CIP data has been applied for.

Printed in China

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

PART ONE

THE HISTORY OF WHISKY

PART TWO

HOW WHISKY IS MADE

PART THREE

THE WHISKY TOUR

PART FOUR

BLENDS & COCKTAILS

GLOSSARY

GLOSSARY OF DISTILLERIES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND PICTURE CREDITS

FOREWORD

‘I’m writing a whisky book’

I said cheerfully to the distiller standing in front of me.

‘Ah, another one’

He replied with a frown,

‘Why d’ya want to do that? There’s plenty enough already and they’re all just lists of lists!’

Good point, I thought. I was at the Kilchoman Distillery on the island of Islay, just off the west coast of Scotland. My companions and I were in the middle of a four-day tour that covered around 20 of the 100-or-so malt whisky distilleries currently operational in Scotland today. It was blowing a gale and lashing down with rain outside on a morning in December, and we were warming ourselves by the glow of the two small copper pot stills.

I didn’t really know how to reply to the man’s question. He was probably twice my age and possessed limitless experience and knowledge of the whisky industry. And he was right; the subject of whisky is an impressively well-documented one. More books have already been dedicated to this category of spirits than any other I know of, and on the face of it, there is little need for another one.

But the same could have been said about Kilchoman Distillery, the very place I was standing when the question was posed to me. Here was a whisky distillery on the tip of everyone’s tongue, attracting visitors from far and wide, yet Kilchoman only began making whisky in 2007. You could have argued that Islay didn’t need another distillery; the seven other operational distilleries on the island had got along quite happily for over 100 years (some of them much longer). Why start a new distillery there now? Whatever the reason it was an astute move. Folk are buying up Kilchoman as fast as they can make it, which is even more surprising given the £50 ($85) price tag for what is, by anyone’s standards, a very young Scotch whisky.

So perhaps a new slant on an old favourite can be an agreeable thing? That’s my hope anyway – that the same thing gravitating us towards the fresh approach that Kilchoman offers also inspires you to pick up this book and discover (or rediscover) the whisky category at a time when it is rediscovering itself.

Whether you are curious about how a young whisky from Islay might taste, or interested in how history shaped whisky in to the world’s largest premium drinks category, puzzled about how a barrel turns a fiery white spirit into a mellow yet complex expression of time, or searching for better ways to enjoy drinking whisky. It’s all in here, because I was curious about these things and the odyssey that I embarked upon helped me answer these questions and many more besides.

This journey taken me to some of the absolute extremities of the United Kingdom, through the ‘bible-belt’ states of Tennessee and Kentucky, on to the whisky bars of Taiwan and the bullet train rides along the length of Japan. I’ve rooted through the history books and into the origins of human civilization, and visited state-of-the-art laboratories equipped with flavour detecting and creating technology concerned with whisky making. I have consumed whisky on remote wind-torn beaches as the sun rises, and in the world’s tallest buildings as the sun sets. I’ve tasted £10,000 ($17,000) bottles and £10 ($17) bottles and found value in both of them. I’ve also made lifelong friends on this journey and spent a lot of time simply sitting, sipping and thinking about whisky all by myself.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

This book can be broadly separated into four different sections, each of them a useful referencing source in their own right, but when put together they form a sweeping campaign of whisky propaganda, general musings, original photography and scientific know-how.

In the first section of this book, I have endeavoured to thoroughly explore the history of whisky, from the origins of alcoholic beverages and distillation and their seemingly inseparable connections to religion, philosophy and spirituality, through to the emergence of medicinal aqua vitae, uisgebaugh and ‘whisky’ itself. In more recent history, I explore some of the cultures, people and politics that have moulded whisky into the global product that we know today.

Then we take an in-depth look into whisky production, from a simple barley grain through to an amber liquid with unparalleled levels of complexity and intricacy. We also look at how some of the most traditional techniques, that still remain in practice today, are now balanced with state-of-the-art renewable energy standards and precise manipulation methods that craft distinct products over a period of years and decades.

In the third section I explore over 55 of the world’s most incredible distilleries, across nine countries and 19 distinct whisky-producing regions. Here we discover what makes these producers create the spirit that they do and how seemingly tiny deviations can dramatically affect the final outcome. I’ve aimed to shed new light on some of the oldest and distilleries in the world, and championed some of the newest, too. Attention has been devoted equally to both small and large operations, and up-to-date tasting notes are included for some of my favourite expressions.

The final section includes some information on how best to drink whisky, including some original cocktail recipes, innovative whisky serves, and a couple of drinks that history has chosen to misplace. Finally, the book ends on five unique whisky blend recipes, which can be constructed by anyone, and are made from whiskies that are readily available to everyone.

Also included in the back of the book is a glossary of terms that will no doubt become a useful referencing point, and a glossary of distilleries, encompassing over 220 active whisky distilleries from around the world.

PART ONE

THE HISTORY OF WHISKY

THE ORIGINS OF DISTILLATION

Distillation is an art based around scientific principles. Its history is a story of scientific technology and the cultural background of the various people who have attempted to master it. In the broadest sense it is a way of separating components of a liquid using heat, be it to purify or ‘split’ a liquid, or to extract the essence of a flower, leaf, fruit or plant in its potent vapours. It is this broad scope of distilling applications that has piqued mankind’s curiosity for the past 5,000 years or so – whether it was a Chinese herbalist concentrating aromatic herbs into boozy steam, a Mesopotamian physician compounding roots and barks into a medicinal tincture, or a Greek philosopher defining the elements upon which the world is founded. The ins and outs of all of these antics will continue to be debated for the next 5,000 years no doubt, but the state of distillation today stands as a legacy to those crackpot experimenters who paved the way.

ANCIENT DISTILLING

It seems that most things of any great significance can be traced back to ancient Chinese civilization, and certainly the Chinese have a long history with alcohol. One excavation of a Neolithic settlement in China found a 9,000-year-old clay pot containing fermented rice remnants – presumably they didn’t clean their pots very well, or perhaps the entire village dropped dead before anyone had a chance. Strange, though, that the first two literary references of Chinese distillation come from as late as the 12th century AD. It is possible that they were just late developers on this occasion, but both of the aforementioned references provide great detail of the ingredients, methods and various types of distillation, giving this reader the impression that by the 12th century these were very well-established practices indeed. Traditional Chinese literature is thin on the ground when it comes to technology and science in general – the penning of classical literature has always been held in much higher regard in China – and adds further weight to the argument that they were more than familiar with alchemical arts at this time.

Some scholars believe that the Chinese knowledge of distillation was shared with Persian, Babylonian, Arabian and Egyptian merchants through their contact along the ancient silk-trading routes that trickled into the Middle East. These 2,000-mile trails were first carved out around 10th century BC, but it took a good 700 years to really get established. Gold, jade, silk and spices were all up for grabs, but it was as a hub of cultural networking that the silk route really came into its own. It was, in effect, the information superhighway of its time.

Whether the Chinese got the know-how from the Indo-Iranian people, or the other way around, the secret knowledge of ardent waters and botanical vapours was beginning to condense down into the classical civilizations. And the pre-eminent philosophers, alchemists and botanists of these civilizations took great interest in it.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle was certainly aware of distillation in one shape or another. One section of his Meteorologica (circa 340 BC) concerns experiments that he undertook to distil liquids, discovering that ‘wine and all fluids that evaporate and condense into a liquid state become water.’

Aristotle

In 28 BC a practising magus (magician) known as Anaxilaus of Thessaly was expelled from Rome for performing his magical arts, which included setting fire to what appeared to be water. The secrets of the trick were later translated into Greek and published around 200 AD by Hippolytus, presbyter of Rome. It turned out Anaxilaus had used distilled wine. Around the same time the Roman philosopher known as ‘Pliny the Elder’ (with a name like that he was surely endowed with a substantial beard) experimented with hanging fleeces above cauldrons of bubbling resin, and using the expansive surface area of the wool to catch the vapour and condense it into turpentine.

The Great Library of Alexandria

The world’s first (self-proclaimed) alchemist, Zosimos of Panopolis, was also thought to be something of a wizard. He provided one of the first definitions of alchemy as the study of ‘the composition of waters, movement, growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and bonding the spirits within bodies.’ It was Zosimos’ belief that distillation in some way liberated the essence of a body or object that has led to our definition of alcoholic beverages as ‘spirits’ today.

The scrolls and ledgers that documented all these works were largely preserved in the great libraries of the time. There is no better example of this than the ancient and epic Great Library of Alexandria, which was thought to have contained over 500,000 scrolls. That was until successive religious and political power struggles during the first half of the first millennium AD caused them to be either sold, stolen or, as was the case with Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, simply given away only to be burned. In the year 642 AD, Alexandria was captured by a Muslim army and the last remaining remnants of the library were destroyed, and along with it the collective knowledge of much of the ancient world. Or so we thought... It would seem that some scraps of information and hastily copied texts still remained, written in ancient languages by long-dead men. The secrets to the mysteries of ardent waters and humid vapours did still exist, secreted away in monasteries and temples of learning dotted around Europe and the Middle East.

ISLAM

It was from these copied documents, amid the rise of the Islamic renaissance, that one fellow, Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan (who in time became known simply as Geber), emerged in what stands as modern-day Iraq as the undisputed father of distillation. It is ironic that we have Islam, a religion that prohibits the drinking of alcohol, to thank for one of alcohol’s most important breakthroughs. Some time around the end of the eighth century AD, Geber invented the first alembic still, which remains the basic form for all pot stills today. The major breakthrough in his still was that rather than using bits of sheep hair or an old rag to collect the spirit vapours, Geber’s al-ambiq incorporated a condensing retort connected by a pipe. With the alembic still, Geber came tantalizingly close to understanding the full potential of distillation in what has to be one of the greatest understatements of all time: ‘And fire which burns on the mouths of bottles due to boiled wine and salt, and similar things with nice characteristics which are thought to be of little use, but are of great significance in these sciences.’

It is thought that Geber’s discoveries were influenced by the works of Zosimos of Panopolis, and that it was not spirits he sought, but the philosopher’s stone and the secret of turning base metals into gold. Geber was misguided in this particular instance, but his work on distillation inspired other Arab thinkers and tinkerers of the time to experiment with the art.

Possibly the earliest example we have of distilled spirits being consumed for enjoyment, rather than medicinally, comes from a poem written in Arabic by Abū Nuwās, who died in 814. In one poem he describes ordering three types of wine, each of which becomes stronger as the poem continues. For the final drink he asks for a wine that ‘has the colour of rainwater but is as hot inside the ribs as a burning firebrand’.

But for the most part, through the ninth and 10th centuries, distilled spirit was used for medicinal purposes only. This was a time of great unsettlement in the world, however. Vikings raided and Crusades gathered momentum, and as armies clashed and merchants traded, the seeds of understanding began to filter even into Dark Age Europe, where Latin-speaking scholarly monks had been waiting with eager patience for this wisdom of the ancients.

The knowledge remained exclusive to only the most worthy individuals, however. The 12th century Italian chemist Michael Salernus wrote of ‘liquid which will flame up when set on fire’ but took measures to write his findings in code lest the information get into the wrong hands. Around 100 years later Arnaldus de Villa Nova, a professor from the University of Montpellier, successfully translated Arabic texts that revealed some secrets of distillation. He went on to write one of the first complete sets of instructions on the distillation of wine, and it is this man that we have to thank for the term aqua vitae (water of life), a name which stuck in the Scandinavian akvavit, French eaux de vie, and of course the Scottish uisge beatha, which was later corrupted to whisky. Around 1300 AD he wrote: ‘we call it aqua vitae, and this name is remarkably suitable, since it really is the water of immortality. It prolongs life, clears away ill humours, strengthens the heart, and maintains youth.’

A 17th century copper engraving of Arabian pioneer Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber).

The title page from German physician Hieronymus Brunschwig’s famous book of 1500 entitled Liber de arte distillandi simplicia et composita, also known as the Little Book of Distillation. It was one of the first books about chemistry and included instructions on how to distil aqua vitae.

EARLY GAELIC SPIRITS

FROM AQUA VITAE TO WHISKY

The big question that we need ask ourselves, though, is what were they doing with aqua vitae? The 14th and 15th centuries seem to be a transitional time for aqua vitae from its traditional use as a medical drug to it becoming a rather addictive social drug. Let us now focus on the British Isles, and chart the evolution of aqua vitae into the beverage known by the gaelic name uisge beatha and its coming of age, as the world is introduced to whisky.

Irish legend cites that Saint Patrick brought distilling to Ireland in the fifth century. This seems like a bit of a stretch to me and a likely case of crediting the man simply because he is a prominent historical figure and, in fairness, a useful bloke to have around (especially where snakes were concerned). I have seen reference made to bronze distilling artefacts found around the ecclesiastical province of Cashel in Tipperary, but hard evidence of this is thin on the ground. What is a likely fact, however, is that Henry II discovered grain-distilling practices when he took the liberty of invading Ireland in 1172. If Henry got it right, it would indeed be one of the earliest examples of distilling in the British Isles that we know of.

There is some evidence to suggest that aqua vitae was being distilled in Ireland for nonmedicinal use as far back as the 14th century. The Red Book of Ossoly (1317–1360), was a record of the diocese written by Richard Ledred, who was bishop, and it includes a treatise on aqua vitae made from wine, but makes no mention of grain- based spirits. In Edmund Campion’s History of Ireland, which was published in 1571, he remarks that during the 1316 Irish Famine that was caused by a war with Scots soldiers, the miserable Irish comforted themselves ‘with aqua vitae Lent long’. He also goes on to mention a Knight from shortly after the same time, who would serve to his soldiers ‘a mighty draught of aqua vitae, wine, or old ale.’

This, of course, is not proof by itself of the consumption of aqua vitae, since Campion wrote the book a clear 200 years after the event. Neither is the following eulogy, which is taken from a 1627 translation of The Annals of Clonmacnoise, originally published in 1408: ‘Richard Magranell, Chieftain of Moyntyreolas, died at Christmas by taking a surfeit of aqua vitae, to him aqua mortis.’

Since the original 15th-century manuscript is lost, we can only guess at the accuracy of the translation and the poetic licence taken. The author’s sense of humour in the pun ‘aqua mortis’ (water of death) has not faded over the years, however, and surely there can be no greater testimony to the recreational enjoyment of aqua vitae at the start of the 15th century than the evidence of death through overindulgence during the festive period. Sadly, some things never change.

Raphael Holinshed describes the aqua vitae he finds in Ireland as a veritable cure-all for the 16th-century man, in his Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1577):

‘Being moderatlie taken it sloweth age, it strengthneth youth, it helpeth digestion, it cureth flegme, it abandoneth melancholic, it relisheth the heart, it lighteneth the mind, it quickeneth the spirits, it cureth the hydropsie, it keepeth and preserveth the head from whirling, the eyes from dazeling, the tongue from lisping, the teeth from chattering, and the throte from ratling: the stomach from womblying, and the heart from swelling, the belly from retching, the guts from rumbling, the hands from shivering, & the sinews from shrinking, the veins from crumpling, the bones from aching, & the marrow from soaking.’

Taking the early Irish references at face value, it would seem that Scotland was a little slower on the uptake. The first reference to aqua vitae in Scotland comes from the Royal Exchequer Rolls of 1494 – which lists the sale of 500kg (1,120 lbs.) of malt to one Friar John Corr ‘wherewith to make aqua vitae’. This order of aqua vitae was to be delivered to King James IV of Scotland no less. The story goes that King James had been campaigning on the island of Islay in the previous year and at some time or other got a taste for the spirit made there. A taste for it indeed, since the order placed in 1494 would be enough to manufacture over 1,200 bottles of whisky by today’s standards!

Despite its apparent popularity with the royal household, it still took a while for aqua vitae to leave a mark on Scottish drinking habits. Most of the references to Scottish alcohol consumption during the following 50 years still refer to beer as the reliable beverage of the masses. Aqua vitae did, however, continue to exist for medical purposes. In 1505 a seal was granted by James IV of Scotland, which gave the Guild of Surgeon Barbers of Edinburgh (barbers were held in high regard back then) a monopoly over the manufacture of aqua vitae, stating that ‘na [other] persons man nor woman within this Burgh make nor sell any aqua vitae within the samen’. And the Scots continued to find other uses for the stuff besides drinking it. In 1540 the treasurer’s accounts contain an entry relating to the supply of aqua vitae for the manufacture of gunpowder.

Around the same time we saw Henry VIII, King of England, begin his long succession of failed relationships. When the Pope denied Henry a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, Henry took matters into his own hands, and in 1534, made the unprecedented step of separating the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church. Just to make sure the point was clear, he disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries, leaving a lot of learned monks out in the cold on their own. Some of these learned men integrated into the local communities and the knowledge that had previously been the preserve only of these religious institutes began to filter through the land and into the farms and workshops of the very grateful common folk. Distilling gradually became a common farmyard practice, alongside brewing beer, churning butter and baking bread.

Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries drastically altered the landscape of England; one of its byproducts was the dissemination of distillation knowledge among common folk, rather than just among monks.

Early stills

Distillation techniques using ‘double pelicans’ (above) and the ‘Rosenhut’ (right), from Brunschwig’s pioneering book.

During the same period it is likely that there were some significant advances in the equipment used to make drinkable spirits. Alcohol for medicinal purposes required very little in the way of still management, but if people were expected to drink and enjoy this peculiar tonic, the equipment would need to be slightly more tailored to the needs of safety and taste. Alembic stills became bigger, due to demand, which in turn improved the quality of the distillate through longer still necks. Conical-shaped stills, ranging up to some 44 gallons/53 US gallons in capacity became the industry – I use the term loosely – standard. ‘Worm’-style condensers (see page 75) were also probably introduced, since they were known to be in use in France and Italy.

Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary of Ireland (1603) gives us an early taste of the production method of ‘good’ Irish aqua vitae at this time, and provides us with one of the earliest examples of the corruption of the gaelic name for ‘water of life’, uisge beatha (pronounced ooshky-bay):

‘The Irish aqua vita, vulgarly called Usquebagh, is held in the best in the world of that kind, which is made also in England, but nothing so good as that which is brought out of Ireland. Usquebagh is preferred before our aqua vitas because the mingling of Raysons, Fennell seed and other things, mitigating the heat and making the taste pleasant, makes it lesse inflame and yet refresh the weake stomache with moderate heat and good relish.’

If you are thinking that this flavoured spirit sounds nothing at all like the whisky you enjoy today, you’re not alone. It would seem that not everyone got the memo about whisky being made from only barley. In 1772 when Thomas Pennant visited the island of Islay he recorded that ‘in old times the distillation was from thyme, mint, anise, and other fragrant herbs’. George Smith’s Compleat Body of Distilling (1766) has a recipe and cost breakdown for ‘Fine Usquebaugh’ that has among its ingredients malt spirits, molasses spirits, mace, cloves, nuts, cinnamon, coriander, cubeb, raisins, dates, liquorice/licorice, saffron and sugar. This, to me, sounds remarkably like a (bad) gin, which is not at all surprising given the goings on of the gin craze that had been overwhelming London for the past half-century. Flavouring spirits was not only frequent during this time, but downright essential if one was inclined to make the concoction drinkable.

So there was no clear identity for uisge beatha during the 1600s, but that didn’t hamper its steady integration into the fabric of society. More and more farms turned more of their attention to the profitable liquor and it developed into an important economic commodity, even being used as part of a rental payment for properties in Scotland and trading with Irish merchants – despite the apparent enthusiasm that the Irish held for making their own. And with the recognition of a growing industry, so too came the inevitable: taxes.

TAXES AND SMUGGLING

The first tax on spirits in Scotland was set in 1644 at a rate of 2 shillings and 8 pence for ‘everie pynt of aquavytie or strong watteries sold within the countrey’, with further increases half-a-dozen times over the following 60 years. After the Act of Union in 1707, the parliaments of England and Scotland were brought together as one, and the same taxes on distillation applied to both. In 1715, the English Malt Tax was put into effect in Scotland, too, and then increased in 1725, making it one of the major contributing factors to the Jacobite uprising and riots that were frequent at the time. But even with heavier taxes, the distilling industry continued to prosper, since uisgebah could also be made from other cereals. This fact also encouraged many of the brewers to turn to distilling.

Seventeenth and 18th-century buildings, thought to be part of the old Ferintosh distillery in the Scottish Highlands.

Let’s get one thing straight, though. For most of the 18th century, this still wasn’t whisky as you know it. It was crudely distilled from a mixture of cereals in a rigged together tin can. The spirit wouldn’t have been cut correctly, at best making it foul and at worst lethal; it was most likely flavoured, and certainly wouldn’t have been intentionally rested in oak barrels. Besides, nearly all of the whisky produced during this time would have been for Scottish or Irish consumption, with London certainly needing no further encouragement to drink as its inhabitants wallowed in the midst of a gin craze.

There were exceptions to the backyard rule, of course. One of history’s most prominent malt distilleries from the same period, and the first large distillery to flourish in Scotland, was Ferintosh. The distillery at Ferintosh became an incredibly lucrative operation after its owner was granted a tax break for support of the new Dutch king, William of Orange, who acceded to the British throne in 1689. No taxes meant the product could be sold cheaply, meaning the other tax-paying distilleries could not compete with Ferintosh.

Growth for Scottish distillers continued up until 1752, with the annual output almost doubling in the space of 10 years. The future looked good until disaster struck in 1757, marked by a massive crop failure that forced the British government to prohibit the sale of distilled spirits for three years. The use of a private still was not prohibited, however, and so long as its wares were used only for household consumption, no law was broken. No enterprising Scotsman in his right mind would lie down just like that and so illicit distilling and smuggling began on a massive scale.

By the time the ban was lifted it was already too late – duty-free whisky had a good taste to it and men had little inclination towards paying taxes. And it was the game of taxation that seemed to govern the prevalence of illicit operations for the next 50 years, increasing dramatically when the risk of being caught was outweighed by the significant rewards. A sudden increase in duty meant the sprouting up of new illicit distilleries by the thousand.

It seems the government was too slow to recognize that things were getting out of hand and excise officers were simply too lenient on those caught in the act of illicit distilling, with early records of some individuals being caught three or four times in a short period. When the authorities did get a handle on the sheer scale of the problem, it was already endemic and far too big to police or manage, regardless of the severity of the punishment.

The risk to the clandestine operatives, of course, was not a particularly great one. The various inaccessible islands, glens and crags of the Highlands (many of which have given their names to present-day legitimate distilleries) provided ample seclusion from the prying eyes of the excise officers, who were also known as gaugers – named for their ‘gauging’ of the malt to assess its duty. The Glendronach Distillery in Speyside is one such operation that picked its location very carefully. Situated adjacent to natural springs, it meant that there was an abundance of clean water, but even better than that was the colony of rooks which nested nearby and were prone to screaming whenever anyone approached at night – as good a security alarm as anyone could wish for.

The ‘legal’ distilleries now had to compete on price with both the duty-free Ferintosh distillery, as well as illicit operations. Many of them reacted the only way that they could, and took measures to fake their customs and excise production declarations in an attempt to reduce their tax bill. The government got wise to this pretty quickly, though, and enforced a series of strict and oppressive measures that aimed to control the few remaining legitimate operations. In 1774 William Pitt’s Wash Act was passed, which required Lowland stills to be a minimum of 400 litres/106 US gallons in capacity and taxed on their size, not their output. Highland distillers were granted more lenient taxes, based on the volume produced, and were permitted to use smaller stills of a minimum 91 litres/24 US gallons. The only problem was that they weren’t allowed to sell it outside of the Highlands. The Wash Act drew a deep line in the sand between how Lowland and Highland distilleries operated, encouraging the distillers in the south to build stills that could distil very quickly, albeit with a significant drop in quality. In the Highlands there was less rush, and the spirit was said to be of a much greater standard than the Lowland swill... but available only in the Highlands.

Distilling for personal consumption was outlawed in 1781. If the illegitimate distillers had ever thought about going back to the straight and narrow, those thoughts had completely gone out of the window by this point. As the 18th century drew to a close, the ongoing Highland Clearances, also known as the ‘expulsion of the Gael’, only served to fuel the fire of resentment that burned for the British government. Any perception in the Highlands that smugglers were wrongdoers or law breakers had been replaced by an acceptance of it as a profession and even as a god-given Gaelic right. Both the duty and the punishment for non-compliance were further increased, and Scots rebelled, resulting in what nearly amounted to all-out warfare.

The rate of taxation on whisky fluctuated greatly over the years, as much as tripling in war time when the British government needed the cash, and settling down again during times of peace.

Whisky would be distributed among towns and villages by ‘bladdermen’, so-called because concealed beneath their britches would be a bladder full of uisge beatha. Highland Park Distillery on the Orkney Islands (see page 160) was known to conceal casks of whisky in the hollow pillars of nearby St. Magnus Cathedral, despite the attending reverend reaffirming ‘thou shalt not make whisky’ in his Sunday service. During the same period it has been estimated that Edinburgh had around 400 distilleries; 11 of which were licensed.

The 1823 Excise Act changed everything, however. Duty on Scottish whisky was cut by more than 50%, down to the manageable rate of 2 shillings and 5 pence per gallon. For many business-minded distillers this was an opportunity to legitimize their operations and increase their business. The Glenlivet, Fettercairn, Cardhu, Balmenach and Ben Nevis are just some of the distilleries that are still operational today which saw their chance and licensed their operations during this time. By 1825 there were 263 licensed distilleries in Scotland, all of them free to produce whatever volume of spirit they wished. Quality naturally improved – since it is so much easier to make good whisky when you don’t have to hide it from anyone – as did quantity, and the operations that chose to avoid the duty were soon forced out of the marketplace, with records of seizure in Scotland dropping from a post-Excise Act high of 764 in 1835 to only two in 1875.

However, the less documented illicit activity in Ireland was either on a considerably larger scale, or policed more vigorously (or both). In 1833 there were 8,233 reported cases of seizure of illicit distilling equipment and the numbers remained in the thousands even up until the 1870s.

The smuggling in Scotland didn’t stop there, mind you, as tax on spirits was much higher in England than Scotland during the 19th century, by over 8 shillings a gallon. Licensed Scotch distillers, many of whom had plenty of experience of the smuggling lifestyle, developed ever more ingenious methods to smuggle their ‘mountain dew’ over the border, even going as far as to train dogs to swim across rivers with pig bladders full of whisky in tow. Practices like that were small time, however. There were bigger operations taking place as some estimates place the volume of Scottish duty-paid whisky crossing the border in the 1820s as upwards of 50,000 litres/10,000 US gallons every week (that’s a lot of dogs). Many of the distillers would travel in armed groups, each carrying 30 litres/8 US gallons of spirit tied to themselves in metal canisters. Most of the time, excise officers were simply too scared to approach them – and who can blame them?

Even up until the 1980s it was normal for excise officers to live ‘on site’ at the distillery. One distillery manager once candidly told me that ‘To be a distillery worker you have to have a real genuine love for drinking whisky, but to be an excise officer you have to have an even bigger love.’

Back in the 1970s at The Bowmore Distillery on Islay, twin brothers John and Roger McDougall were the acting customs excise officers – just to make things even more confusing. The brothers apparently had a passion for making their own spirits, Alastair McDonald from Auchentoshan tells me. While working at The Bowmore at the tender age of 17, he was cornered by the two big officers and asked: ‘What do you drink, McDonald?’ Alastair assumed that something had gone missing in the distillery and quickly replied, ‘Nothing.’ The brothers produced a bottle of something dark and held it under his nose, apparently looking for a response. When none was given they told young Alastair to drink the liquid, which tasted like coffee. Alastair gave the pair a pleading look, and they responded by telling him ‘It’s our homemade Tia Maria – d’ya like it?’

The pillars of St. Magnus Cathedral on the Orkney Islands, some of which would have been secretly filled with casks of Highland Park whisky in the early years of the 19th century, unbeknownst to the vicar!

NEW WORLD, NEW WHISKEY

The story of distillation in North America starts with rum. The early colonists didn’t trust water, so turned to hard cider and beer as their staple beverages. However, something stronger was needed for the cold winter nights, and rum was the answer. Rum flooded into North America from the Caribbean during the 1600s, as well as sugar and molasses – the building blocks required to make one’s own rum. Many households owned rickety alembic stills that could be used to distil mead, pear cider and hard cider into spirit – a job invariably conducted by the woman of the house – but the cheap and ready supply of molasses made rum the most economic choice for those seeking intoxication. In 1750 Peter Kalm, a Swedish-Finnish traveller, noted in his Travels into North America that colonists believed rum to be a healthier choice over imported spirits made from grain, even going as far as to point out that fresh meat stored in rum will ‘keep as it was’ while in other spirits it would be ‘eaten full of holes.’

Nevertheless, there are records of corn and rye beers being made in Connecticut from the middle of the 17th century. In fact, the earliest known record of any kind of distillation in North America is of the Dutch on Staten Island (which was a Dutch Colony at the time) in 1640. The distiller was William Kieft, and he also owned a tavern, which was the only place you could buy his creations. Bottled products included brandy and some kind of crude whiskey made from the leftover dregs of beer. This was a relatively common practice in the years to come, since grain was much more expensive than molasses.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon mansion in Virginia in the late 18th century. In 1797, he hired a Scottish plantation manager, who encouraged him to build a whiskey distillery. By 1799, the distillery they had created was the largest in the United States.

Jump forward 100 years, and not much on the back bar has changed, but rye and corn-based spirits were beginning to gain popularity. George Washington, a man who clearly liked a drink, operated one of the largest distilleries in North America out of his Mount Vernon Estate in Virginia; it was making rye whiskey. During the American War of Independence he was known to remark that ‘The benefits arising from the moderate use of strong liquor have been experienced in all armies and are not to be disputed.’ The same man had a barrel of Barbados rum delivered to celebrate his inauguration as the first President of the United States in 1789.

Corn whiskey probably lagged behind rye a bit. Maize was still an exotic, New World commodity, whilst the rye that had been brought over by German settlers originally was a familiar Old World product that was easy to cultivate and familiar to brewers and distillers.

As settlers expanded the frontiers and headed south, into modern day Kentucky and Tennessee, the soil and climate changed. Where rye flourished in the colder north, colonists soon learned from native Americans that ‘Indian Corn’ crops grew better in the humid heat. Not only that, but corn could even be planted in-between other crops and even trees without the need for levelling off the land beforehand. Just like the gold rush of the mid-1800s, the difference being that this gold was edible, New-Worlders flocked to the area to stake their claim on land and to grow this energy-packed, new fangled food source. Some of these early settlers had familiar names like Beam and Weller. They, along with many others, were the forefathers of the great whiskey tycoons of the 19th century.

A tax collector is tarred and feathered in Pennsylvania in 1794 during the Whiskey Rebellion.

Corn was exported by the boat- and barrelload. The two major trading routes from the western frontier went either to the Eastern seaboard, or down-river to New Orleans. Without railroads or motor vehicles, both were long, arduous journeys that required a significant animal and human workforce to cart the barrels of milled corn. It made far more sense to convert the corn into liquor and pop that in the barrel instead. With the weight reduced by 80%, but the value remaining the same, a horse could effectively carry five times the load. Distillation operations popped up like worms out of the ground: basic as can be and dangerous to boot. These were not artisans crafting fine-quality liquor; they were always ancillary to farm operations, made by business-minded farmers, reducing costs and maximizing profit.

The production network was established. What was needed next was a market for the product. Politics was the answer – America gained its independence in 1789. The ‘Demon Rum’ that had built the colonies was a British invention and a recent memory of colonial rule that had birthed the slogan ‘No taxation without representation’. President John Adams himself admitted that ‘Molasses was an essential ingredient in American Independence.’ Rum was most definitely out of favour. The United States looked inwards for a new spirit of America. The answer was whiskey.

It is a historical fact that when there is big demand for a product, as there was with whiskey during this time, there will always be a taxman ready to take his cut. Continuing to mirror the goings on in Scotland 150 years previously, in 1791, only two years after independence, an excise duty on spirits was passed that required cash payment to the government based on the production of spirits. The aim was to make up the huge deficit that the war had cost the nation, but farmer-distillers felt cheated – the independence that many of them had fought for during the war was being pulled out from underneath them. It sparked rebellion, which was particularly prevalent on the southwestern frontier and across the Appalachian region that stretched all the way from New York down to South Carolina. The new government demonstrated for the first time that it was willing to use violence to suppress the uprising, but collection of taxes was minimal and the tax was repealed in 1802. Sixty years later it was reinstated, but it was much less of a problem at that time, since the government was buying huge stocks of whiskey to fire up its Civil War troops.

BOURBON

It’s fairly easy to work out where rye, corn, Canadian et al. got their names, but to Brits, bourbon is a type of chocolate biscuit/cookie, right? To tell that tale we must first look to France. Louis XVI was King of France from 1774 to 1792, and a strong ally of George Washington during the War of Independence. As a sign of America’s gratitude to Louis – mostly for supplying weapons – after the war, a huge swathe of land that included 34 modern-day Kentucky counties was named after Louis’ house name, Bourbon. Some say that it was actually the French general and war hero Lafayette, also descended from the French royal house, who the county was named after. Either way, the Americans liked the French during this period – Bourbon County was an obvious reflection of that.

As time went on, the French connection was forgotten and Bourbon County got smaller. The state of Kentucky was formed, but ‘Old Bourbon County’ whiskey continued to be traded in New Orleans. As the barrels of liquor bobbed up and down the Mississippi River (not literally – they would of course have been on a boat) towards the port, they had lots of time to mellow and integrate with the wood in the southern sun. The whiskey became famous for its quality and the name of bourbon became synonymous with it.

The title of being the first producer of bourbon is a hotly contested one. Many attribute it to Evan Williams in 1783, though solid evidence to back it up is scarce. Others pick out the preacher, Elijah Craig, claiming that he was the first to age whiskey in barrels. Allegedly, Craig used barrels that previously held pickled fish (for reasons of economics, not flavour); so as to remove the smell, he would char the inside. The simple act of charring a barrel opened up a whole new world of whiskey complexity to his liquid. Other historians believe that the char was a sterilizing measure, put in place during a time when casks were used for fermentation of the wash. Then there are Oscar Pepper and James Crow, distillers through the 1830s and 1840s who perfected many of the methods that are essential to good bourbon production today. Bourbon whiskey is not a product of any single man’s endeavours, but a concerted effort by many men, across multiple generations, compelled and coerced for reasons of economics, geography and the pursuit of a better product and a stronger brand. And what we do know is that the first known advertisement for bourbon whiskey was published in the Western Citizen newspaper, in Paris, Kentucky in 1821.

Bourbon County in Kentucky is named in honour of Louis XVI’s family name, in thanks for supplying weapons to George Washington during the War of Independence.

The mid-1800s saw the introduction of the column still, which now features in many modernday bourbon whiskey distilleries. This meant an increase in production, due to the continuous nature of the apparatus. It also meant greater consistency – another strong selling point to the thirsty public. As frontiers stretched out to the Old West, it was bourbon whiskey that cowboys called for in saloons.

In 1850, the Louisville & Nashville Railroad was chartered and began connecting Louisville to markets not serviced by the traditional steamboat trade. The growing railway system caused a significant change in the bourbon industry. Distilleries no longer had to be located near gristmills or flowing streams or rivers. The railroad could bring large quantities of grain to nearly any location in the state and could transport full barrels of whiskey to market. This allowed bourbon distilleries to locate in Louisville and offer a better service to the whiskey merchants on ‘Whiskey Row’. For example, the Old Kentucky Distillery was established in 1855 along a railway on the outskirts of Louisville. And in 1860, the Early Times Distillery was built at the Early Times Rail Station in nearby Nelson County – it is still there today.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Kentucky, a border state, found itself trapped between both sides of the conflict. The fact that Kentucky remained part of the Union, but still permitted the ownership of slaves, made it about as neutral as was possible. Some stories from that time suggest that when Union soldiers were in town it would be the American flag that was flown, and when Confederates came by it would be the Confederate flag. Both armies drank bourbon recreationally, as well as using it for cleaning wounds and no doubt raising spirits.

The end of the Civil War also saw the introduction of a government-controlled distillery licensing system. This system made small-scale distilling a legally cumbersome and expensive activity. The days of small-batch production and the farmer-distiller tradition were numbered.

In Louisville, the bourbon business saw the development of new trading houses, including J. T. S. Brown (later Brown-Forman). These companies resumed the practice of buying whiskey in bulk from rural and city-based distillers and vatting them together to create proprietary flavour profiles. The vatted whiskies were then rebarreled for sale in bulk lots to wholesalers, retailers, doctors and pharmacists.

Louisville, the largest city in Kentucky, in 1872

As a new century closed in, everything was looking good for American whiskey. In fact, it would have been perfect were it not for the murmurs of temperance coming from the sidelines. Those murmurs were gradually turning into shouts, and it slowly became clear that Prohibition wasn’t far away. And with it would come the near-complete collapse of the entire whiskey industry. Things would never be the same again.

CANADA

In Canada, the earliest known occurrence of distilling goes back to James Grant’s rum distillery in Quebec City, around 1767. As is usual, it is the cheapest ingredient that gets distilled first, and during that period it was molasses. But one thing Canada was not short of was land, and the colonists soon got to work planting all manner of crops.

Gold prospectors in Canada in 1900, following in the footsteps of George Carmack, who struck it rich on a stream in the Yukon four years’ earlier. Many prospectors struggled to get by, and often spent the little they had on whisky.

In terms of brewing and distilling, it was probably Scottish immigrants who kicked things off, which might be why Canadians, like the Scots, drop the ‘e’ from their spelling of whisky. Either way, Canada was a melting pot of experienced booze producers from France, Scotland, Ireland and England. Each European nation had brought its own cereal offering to the table, too. The Dutch and Germans came with rye; the English brought barley and wheat. Indigenous corn flourished in the south and rye did just as well in the cooler northern areas.

But the most popular cereal for distilling in the early 1800s was wheat. Wheat was milled down for bread-making and the glamorous-sounding but apparently not particularly useful ‘wheat middlings’ were sent to be mashed and distilled. Barley was malted and used for its enzymatic benefits, and eventually rye became a seasoning of pepper over the top of the ‘mash bill’: the different grains used for mashing.

One of the first whisky distilleries, and certainly the most successful of its era, was that of the Molson family of Montreal. Molson is the second-oldest company in all of Canada and better known for its brewing empire. But before beer became their bread and butter, Thomas, the son of founder John Molson, took a trip to Scotland in 1816 and embarked on a tour around a bunch of distilleries. He recorded what he saw, and, convinced that whisky was the next big thing in Canada, built his own distillery a few years later. Other whisky distilleries materialized, keen to get a piece of the pie, and in 1827, only six years after Molson had sold his first bottle, there were 31 known distilleries in lower Canada. Another six years later and that number is believed to have tripled in size.

Reports from this time indicate that this ‘whisky’ may have only been distilled once, meaning that it was likely no more than 20% ABV and more than a little ‘ragged’ around the edges. Exported stuff, by Molson at least, was apparently distilled twice in order to ensure its survival on the long voyage over to the United Kingdom or across the United States.

In 1840, distilling licences were up for grabs and reports from the time show that there were over 200 distilleries across Canada; today there are fewer than a dozen. The demand for Canadian ‘rye’ whisky (see page 204) was high as well. In 1861, America was thrown into Civil War, where whiskey distilling was outlawed in the South (stills were used to make cannons) and heavily taxed in the North. Canadian whisky happily picked up the slack and the void was filled. In 1887 Canada was the first nation to put a minimum ageing requirement on whisky. The minimum age was one year, which was increased to two years in 1890.

Canada played an important role during Prohibition in the USA, providing a steady flow of liquor, namely Canadian Club – which has had a strong following ever since, to thirsty American people. At the height of Prohibition there were thought to be over 1,000 bottles of Canadian Club crossing the US border every day.

These days, Canadian whiskies share similar mash bills to that of bourbon – corn-dominated, but with some rye or wheat overtones. There are some 100% rye whiskies, too, most notably those produced by Alberta Distillers Ltd.

WHAT IS WHISKY?

Up until this stage in our story, whisky made in Scotland was sold and produced only as a single product from a single distillery. The Excise Act of 1823 encouraged illicit distillers to hit the straight and narrow, and many did, but even after that you would have been hard-pushed to find a bottle of Scotch whisky outside of Scotland, and over 90% of the malt whisky made in Scotland never crossed the border. Winston Churchill once attested to this: ‘My father would never have drunk whisky, except when shooting on a moor or in some very dull, chilly place. He lived in an age of brandy and soda.’ The truth is that the whisky of the early 19th century could not compete with the finesse of French brandies. The changeover kicked off in 1830, but it would take another 60 years for all of the cogs to align correctly and Scotch to make its true impact on the world.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONTINUOUS STILL

It started with new advances in distillation. Whisky had always been made the same way, fermented from malted barley and distilled in a big onion-shaped kettle. It was a time-consuming ‘batch’ process that produced only a little liquor for a lot of effort, and required the cleaning and resetting of all the equipment before it could be repeated. At the time it was also highly inconsistent, almost all of the 330 or so distilleries had previously run as illicit smuggling operations, and despite their now legitimate operations, many of their practices remained crude, inconsistent and ‘boutique’, to put it nicely. But this was the early 1800s and with the industrial revolution grinding into motion, an alternative was needed to the primitive ways of old: a device that could continuously distil alcohol.

Irishman Aeneas Coffey is usually credited with inventing the first continuous still in 1830. However, those of us in the know are aware that the true inventor was actually Robert Stein, in 1827. But what most people don’t know is that Stein relied on earlier designs to make his still, too. To discover more about that we must travel to 19th-century France.

Despite being illiterate, French-born Édouard Adam attended chemistry lectures under Professor Laurent Solimani at the University of Montpellier. Adam developed and patented the first type of column still in 1804, except the column was horizontal rather than vertical and based on laboratory Woulfe bottles (sequential bottles linked by pipes). It worked by linking together a series of what Adam called ‘large eggs’, with pipes that would transfer alcohol vapour from one to the next. The concentration of alcohol increased in each subsequent egg, while the leftover stuff was recycled back at the start. It wasn’t truly continuous in its design, but it certainly paved the way for stuff that came later down the line.

Adam died in 1807, but his rivals continued to improve the design, with such inventions as the Pistorius still, patented in 1817, which was the first still to be in a column shape. Steam was pumped up from the bottom and beer from the top and distillation took place on a series of plates. The feints were recycled and fed in again at the top.

Subsequent iterations were developed by the French engineer Jean-Baptiste Cellier Blumenthal and a mysterious Englishman known only as Mr Dihi. It tended to be the case that these stills incorporated one or two elements of the continuous still as we now know it, but never all of them working in unison. It wasn’t until Robert Stein came along that it eventually happened.

Frenchman Éduoard Adam built upon the principle of the Woulfe bottle and in 1801 patented the first still to produce alcohol in one operation.

Robert Stein came from strong distilling stock. His father, James Stein, established the Kilbagie Distillery in Fife in 1777, one of the largest distilleries of its era. Robert went on to run it, and with the new Excise Act in place, he set about expanding his legal operation. Stein patented a new type of still, shaped like a column and split into a series of small chambers. The wash was pre-heated, then pumped into the chambers where it came into contact with steam. As the vapour rose, the steam stripped the spirit away, and anything that wasn’t alcohol condensed on one of the fine hair meshes that were dotted around inside the contraption. Spirit and waste were collected separately and the process continued.

The patent still was a licence to print alcohol, but on the negative side, the purchase of a patent still was a huge investment, costing many times more than a simple pot still. But this type of distillation produced a much lighter, cleaner and more delicate spirit that was cheaper to produce and up to 94% ABV. (For a more detailed look at the continuous still, see page 78)

Just as the first orders of Stein’s still were being delivered, another still was invented. An Irishman named Aeneas Coffey, who had formerly been the Inspector General of Excise in Dublin (and had no doubt seen a few stills in his time), patented his still in 1830. It had a few marked improvements over Stein’s: larger processing power (3,000 gallons/3,600 US gallons of wash in an hour), greater purity of distillate (up to 96% ABV) and a much cleaner design. One of the best parts of the new ‘patent still’ was that pipes containing the cool wash entering the system doubled up as condensing coils for the hot alochol vapours exiting it – like a dog eating its own tail. It was a work of genius for its time, reflected in the fact that it is still the same basic design that is used all over the world today.

The first continuous stills were made from iron, and the results were apparently disgusting – so bad, in fact, that the spirit was passed on to gin distillers to be re-distilled and flavoured. Experiments then took place with copper and wooden continuous stills, and the favourite today is, of course, steel.

Stein’s design quickly lost favour, the last one being installed at Glenochil in 1846. Coffey’s went on to dominate and became a favourite of the Lowland distillers, marking a clear divergence of Lowland distillers from the Highland style, which still remains in place today. This divergence from one another would later become a huge matter of dispute between the traditional malt distillers of the North, and the industrial grain distillers of the South. They were producing two entirely different products – the powerfully flavoured malt whisky was in shorter supply, inconsistent and costly, while there was an abundance of the bland grain whisky, so much so, that the distillers were finding it hard to shift it all. The solution was blending.

BLENDS