Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

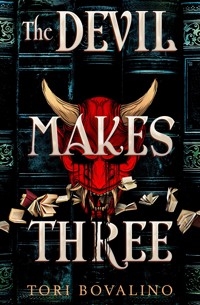

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

The devil seeks his due from two unsuspecting students in this YA horror novel for fans of The Library of the Unwritten and VE Schwab. When Tess and Eliot stumble upon an ancient book hidden in a secret tunnel beneath their school library, they accidentally release a devil from his book-bound prison, and he'll stop at nothing to stay free. He'll manipulate all the ink in the library books to do his bidding, he'll murder in the stacks, and he'll bleed into every inch of Tess's life until his freedom is permanent. Forced to work together, Tess and Eliot have to find a way to re-trap the devil before he kills everyone they know and love, including, increasingly, each other. And compared to what the devil has in store for them, school stress suddenly doesn't seem so bad after all. This is a fast-paced YA crossover/gothic horror debut, with a strong romance and an eerie, page-turning plot that will make this a great choice for fans of VE Schwab and Library of the Unwritten by AJ Hackwith. The book is the perfect blend of dark humor, supernatural suspense, and rich, compelling characters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 469

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

One: Tess

Two: Eliot

Three: Tess

Four: Tess

Five: Eliot

Six: Tess

Seven: Eliot

Eight: Tess

Nine: Eliot

Ten: Tess

Eleven: Tess

Twelve: Eliot

Thirteen

Fourteen: Tess

Fifteen: Eliot

Sixteen: Tess

Seventeen: Tess

Eighteen: Eliot

Nineteen: Tess

Twenty: Eliot

Twenty-One: Tess

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three: Tess

Twenty-Four: Eliot

Twenty-Five: Tess

Twenty-Six: Eliot

Twenty-Seven: Tess

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine: Tess

Thirty: Eliot

Thirty-One: Tess

Thirty-Two: Eliot

Thirty-Three: Tess

Thirty-Four: Tess

Thirty-Five: Eliot

Thirty-Six: Tess

Thirty-Seven: Eliot

Thirty-Eight: Tess

Thirty-Nine: Eliot

Forty: Tess

Forty-One: Eliot

Forty-Two: Tess

Forty-Three: Eliot

Forty-Four: Eliot

Forty-Five: Tess

Forty-Six: Tess

Forty-Seven: Eliot

Forty-Eight: Tess

Forty-Nine: Eliot

Fifty: Tess

Fifty-One: Tess

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three: Eliot

Fifty-Four

Fifty-Five: Tess

Fifty-Six: Eliot

Fifty-Seven: Tess

Fifty-Eight: Eliot

Fifty-Nine: Tess

Sixty: Tess

Sixty-One: Eliot

Sixty-Two: Tess

Sixty-Three: Eliot

Sixty-Four: Tess

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Devil Makes ThreeTrade Paperback edition ISBN: 9781789098136Illumicrate edition ISBN: 9781789099676E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098143

Published By Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 OUPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition September 202110 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2021 Tori Bovalino. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For my parents,

who are significantly better

than the ones I write about.

one

Tess

Tess Matheson was one of the few people on campus who didn’t think that the Jessop English Library was haunted. This wasn’t because of a lack of belief in the paranormal. Tess, who’d grown up under the watchful presence of a host of ghosts that haunted her family’s central Pennsylvania farmhouse, considered herself to have a particularly keen sixth sense. The Jessop Library never gave her any hair-raising or spine-tingling sensations beyond the regular chills from the abnormally forceful air conditioner.

If anything was haunting Jessop, it was Tess Matheson herself. And for the first time in her employment there, she was late for work. A miscalculation on her part: too long spent playing her cello, stealing whatever time to practice she could.

She considered her options as she power walked up Dawson Street and took a detour through the alley between her favorite Indian restaurant and a frat house. It was possible she would get there in time—but no, she couldn’t vault over the chain-link fence of the parking lot in her favorite pair of white lace shorts. Another miscalculation.

It was also possible that Aunt Mathilde wouldn’t notice that Tess was late. Possible, but unlikely.

Mathilde—or Ms. Matheson, to the rest of the students at Falk—had a reputation. There used to be three other students working at Jessop before they violated Mathilde’s strict code of conduct. One, a sophomore, had accidentally spilled coffee on some printouts that belonged to Dr. Birch. The second, a junior, was let go after he let a student check out books from a senior’s research carrel. The final student was released the first week of summer after showing up late.

Just like Tess.

And that wasn’t counting the students who’d been fired before Tess even got to Falk, the ones Regina was all too happy to tell her about. Part of Tess wondered if the only reason she’d managed to get a work-study there was because they couldn’t keep anyone employed at Jessop for very long.

Tess threw open the heavy door of the English building and rushed through the hallways to Jessop. It was early enough in the morning that she was the only one in the halls. The building smelled of lemon-scented cleaner and pencil shavings. Normally, this was one of Tess’s favorite times of day, when the building was quiet and clean and deserted. But today, when she punched her ID number into the keypad outside of the door, the clock read 9:07.

Everything was terrible.

“Theresa?” she heard, barely before she had the door open. No matter how many times Tess had asked Mathilde to call her by her nickname, her great aunt always used the same incorrect pronunciation of her full one. It was always “Tur-eh-sa” to Aunt Mathilde, never “Tess” or “Tar-ee-sa” or even her sister’s personal favorite, “Tessy.”

“Sorry I’m late,” Tess said, pulling open the other door until it clicked into place. She knew Mathilde hated excuses more than anything, so she didn’t bother offering any. Instead, Tess took the velvet display case covers from Mathilde’s pale, withered hands and set to folding them.

Mathilde sighed. There was something unspoken in that small noise. A warning. A you-know-what-strings-I-had-to-pull-to-get-you-here. And worse, the stern look at Tess that said if-anyone-else-was-here-I-couldn’t-ignore-this. She wrapped her ever-present cardigan around her thin shoulders and shuffled towards her office. “I have a stack of requests for you to find. I’ll bring them out.”

It was only when Mathilde was out of sight that Tess felt her shoulders relax. She slipped her bag off and stowed it under the circulation desk, taking a deep breath of dusty air.

The Jessop English Library was the undeniable golden child of Falk University Preparatory Academy’s campus. The reading room was paneled with shining wood and lined with five floors of balconies. Each floor had fifteen offices, which seniors used in their last year of studying as they put together their final projects. If Tess was still here for her senior year, she’d claim one on the fifth floor, where she could spend all day looking down at the reading room instead of bustling around it.

“Theresa?” Mathilde called again, as if Tess had run away in the time her great aunt had spent walking to her office and back. Mathilde walked halfway into the reading room and abruptly stopped, like going any further would mean spontaneous combustion. She held a book in one hand and a nauseatingly large stack of requests in the other. “Can you find these?”

“Okay,” Tess said, taking the papers. It wasn’t like she had a choice. Usually, someone requested a couple of books at a time, maybe as many as ten. This stack, though… Tess thumbed through the papers. She gave up counting when she got to twenty-five.

“It’s a big one,” Mathilde said. Her voice was as thin and frail as old paper. When Tess was younger, Mathilde always made her think of a story her mother used to tell her, about a woman who died and became a butterfly. In Tess’s eyes, Mathilde, who’d never been young for as long as Tess had been alive, was half butterfly wings herself.

“Do your best not to be late again, dear,” Mathilde said, giving Tess another significant look before turning back to her office. She didn’t tell Tess she got special treatment. She didn’t have to.

Tess counted more from the stack of requests. This many would take her hours to locate, if not days. And the stack was another reminder that she’d be spending her summer here, in Jessop, or at Emiliano’s, where she waited tables.

This was not a comfortable home, no matter how much she tried to rearrange herself into a Falk-shaped box, no matter how much she worked to act like she loved this, if only to convince Nat.

On days like this, when she still had the memory of the scent of dewy grass in her nose and the sun shone vividly through the windows, the idea of sitting in the library was unbearable. It was one of those thick, rare mornings that flung itself right into summer, made for spreading blankets on the quad and rolling her tank top over her ribs to catch some sunlight. It didn’t help that today was a Wednesday, which meant that her library jail time would be followed by an extended probation at Emiliano’s.

And now, she couldn’t even sit in a patch of sunlight and pretend she was outside—because she had to go to the stacks and find those books.

She grabbed a cart and steered it back to the staff area. Jessop was a closed stack system, which meant that patrons weren’t allowed past the reading room. The seven floors of books were only accessible to staff, who had to pull everything. Even so, the stacks were a little too secure. To get back there, she had to use a staff key to unlock the door to the stacks and another key if she needed into the cages.

The smell of dust, faded ink, and old paper immediately surrounded her. There was no metallic tinge of technology back here, no hair-and-skin scent of other humans. In the stacks, Tess was alone, surrounded by ink and paper.

She was in a sour mood by the time she keyed herself into the cage on the first floor. This was her second-least favorite part of the stacks. On the first floor, there was barely any Wi-Fi and never any people. It was impossible to tell what noises were from the old building shifting and what were from a potential axe murderer coming to kill her in the depths of the library.

On the bright side, it wasn’t the basement. The basement cage was even worse.

Instead of focusing too much on the noises, Tess put in her headphones and flipped to the concerto she was practicing for Friday. She could wall herself off, imagine the movements of her own hands over the body of her cello as she worked. When she couldn’t hear any of her thoughts over the sound of Barber, she flipped to the first of the requests and began to search.

All the books were for the same patron: Birch, Eliot. Status: FUFAC. Really, it was unfortunate, Tess thought, that Falk leaned into the F-U branding.

It was like this. Person: Where do you go to school?

Tess: Falk. FUA Prep.

Person: Well, FU too!

Tess: withers in exhaustion.

The same thing, repeated over and over again. It didn’t matter that Falk was one of the best high schools in Pennsylvania. That nearly every graduate got a full ride to college for either academic achievement or from the trustees. It was always just FU.

And to make matters worse, Tess knew exactly who Eliot Birch, FUFAC, was. She could see the cruel curl of his thin upper lip and the glint in his brown eyes. Though she’d never heard his first name, Eliot Birch could be none other than Dr. Birch, the headmaster.

Unfortunately, Dr. Birch was one of the first people she’d met at the school. Tess and her sister Nat’s enrollment at Falk was the result of years of favors to Mathilde called in at once. Their presence broke multiple rules: no students admitted midterm, no students admitted without entrance exams, no scholarships awarded for the year past January. They were only here because of Mathilde’s flawless thirty-year record at the school and the board’s general respect for her.

It also wasn’t a secret that Tess didn’t fit in. She and Nat weren’t wealthy, like the regular kids. Nor was Tess anywhere near smart enough to be a scholarship student, even if Nat was. If anything, Tess scraped by here and would’ve been out of luck if her roommate Anna hadn’t tutored her.

Based on her brief, tense meeting with Dr. Birch, it was clear no matter what Tess or Nat did to prove themselves, he would never think them worthy of places at his school.

But that was the arrangement they had. Tess and Nat were admitted to Falk based on nepotism alone—not that they didn’t have good grades back home, which they did, Nat especially. But grades were such a small factor in the decision of who was accepted into the school.

It was not a comfortable agreement, and she was reminded of that every time she had the misfortune of running into Dr. Birch. But she cared about Nat’s future, and so she dealt with it.

At least, this time, she could take some enjoyment in the easy insult that was already there. Every time she added to the ridiculous Dr. Birch’s stack, who she considered to be one of the authors of her misery, she was rewarded with FUCK YOU FAC. Book one: Magyc and Ritual. Birch, Eliot. Fuck you too. Book two: Witches of Southern Wales. Birch, Eliot. Fuck you again, Birch. Book seven: Alchemy of the Stars. Birch, Eliot. Fuck you a thousand times to the edge of the Milky Way and back again.

By book twenty-three (Rituals of the British Isles), she was pretty certain the headmaster could feel the force of her annoyance from whatever hellhole he occupied around campus.

And she wasn’t even a quarter of the way through the request stack yet.

There were a million things she could’ve been doing: practicing the concerto for Friday, conducting in front of a mirror, checking in on Nat. All these options were more desirable than being in this cage, where she felt more trapped in this dull life than anywhere else on campus.

“Theresa?” Mathilde’s thin voice floated down the stairs in the silence between the concerto ending and beginning again.

Tess abandoned the books half-loaded into the dumbwaiter and ducked out of the cage. She could just see Mathilde’s thin, wrinkled ankles and orthopedic flats at the top of the stairs above her.

“I’m coming,” Tess called, pulling her headphones out and looping them around the back of her neck. She hurried up the stairs, stopping a couple of steps below Mathilde. “What do you need?”

“Are you busy?”

It took all of Tess’s effort not to roll her eyes. Of course she was busy.

“I can make some time,” she hedged.

“A few requests came in.” She had another unbearable stack of papers in her hand.

It was one of those moments when Tess fantasized about quitting. She’d done this a few times, mostly during spring semester, when the sting of turning down her music scholarship and choosing Falk instead was still searing on her skin. But in the end, she’d made this choice months ago. Coming to Falk was the only way to make sure Nat’s future was taken care of.

Tess held her hand out for the stack. Mathilde passed it to her, saying, “Take your time.”

She glanced down at the name on the pages. Birch, Eliot. FUFAC.

Hopefully, Dr. Birch would find some sort of protection charm in the magical books he was requesting. Because if not, Tess was fairly certain that she was going to murder him.

She had to send the first round of books up the dumbwaiter to the cart so they wouldn’t be in an ungainly pile in the cage. Tess darted up the stairs to the cart and was passing the office supply closet when she noticed the boxes full of sticky notes.

Tess considered the closet. It would make her feel better to write down what she really thought, especially since she could just crumple up the notes and toss them later. And she had her favorite pen tucked behind her ear, already inked with California Teal.

She hated how awful she felt, both because of her job and her tenuous position at Falk. She hated even more that Birch had power over her—that everyone had power over her, and that she had so little of her own.

It would eliminate some of the tedium, at least. One reckless, wasteful thing that she would obviously clean up before there were consequences. Tess grabbed a stack of sticky notes.

When she got back down to the stacks with the notes, she didn’t hold back. Every few books got a bright yellow square with a new, horrid thought about Eliot Birch.

Eliot Birch is a fuckmonkey.

Eliot Birch’s family tree must be a cactus because everyone on it is a prick.

Eliot Birch’s birth certificate is an apology letter from the condom factory.

When she had Wi-Fi, she googled one-liners. When she didn’t, she entertained herself by coming up with the crassest insults she could imagine. By the time Mathilde called down to tell her that it was nearly 4:00, the carts of books were peppered with sticky notes of insults.

When Tess changed for Emiliano’s, she had a trace of a smile. She almost felt better about Dr. Birch as a human being.

Almost.

two

Eliot

It was the sunniest afternoon Eliot Birch had ever seen in Pittsburgh, and he detested it. Eliot shuffled down the escalator towards the tram that would take him to baggage claim—really, what airport needed a goddamn dinosaur greeting people?—and tried to imagine he was back amidst the gloom of London.

Eliot joined the other dead-eyed travelers on the tram. As he leaned against the doors, he closed his eyes and shrugged off British Eliot like a worn coat. Tried to imagine smiling wider, talking louder. Walking taller, head high. He tried to stifle the magic in him, thrumming like a crackling of static just under his skin; to push it back into dormancy. Turn his sardonic humor into something lighter, less self-deprecating.

When he opened his eyes, American-passing Eliot was slipping not-so-neatly back into place. A disguise. A survival instinct.

He wanted to be home. He wanted to get on a plane and never set foot in America ever again. Instead, he dropped his headphones around his neck, shuffled off the tram and down two more escalators to baggage claim, and waited for his beaten gray luggage to appear on the belt.

Eliot had taken a tincture in the airplane loo before descending, and he felt even odder because of it. He’d found it just before leaving his mother’s house, squirreled away in the back of a forgotten cupboard in what was once her workroom. This one, simply marked Awake in his mother’s careful handwriting, did make him feel more energetic. Unfortunately, it gave his right eye a terrible twitch and made his mouth taste awfully of sulfurous boiled eggs.

The only relief was that his father wasn’t here. He had a meeting or a dinner or a murder and couldn’t come to scrape his son from the airport, even though it was on his orders that Eliot spend the summer in Pittsburgh. Instead, Eliot was to hail a cab or take a bus or walk. The details were fuzzy. Sunshine made Eliot’s thoughts more jumbled than usual.

He had no desire to go back to his single dorm on Dithridge Street, a luxury he’d demanded for the sake of his sanity and his father had begrudgingly agreed to, so he asked the driver to take him to Jessop. The library was Eliot’s favorite place on campus—not that any of the staff knew. He usually only went there at night, when his insomnia was thick and vicious, and he could safely key in with his father’s passcode and no spectators.

Today, though, he’d deal with other people.

He leaned his head against the cab window and watched the trees along 376 East rush past his window. The first time he’d come, it was a surprise how the city materialized out of the tunnel. London was too big, too sprawling to simply hide behind a mountain. But here in Pittsburgh, it was this: trees, tunnel, and then, after a moment of breathless sunlight, river and city. He was fourteen that first time he saw it, but still, he was awed for only a moment before he went right back to hating it.

“You in college, kid?” the cab driver asked.

“No,” Eliot said, and the answering silence was so awful and interrogative and American that Eliot cleared his throat and said, “I’m going to be a senior in high school. I go to Falk.”

“Ah, Falk,” the cabbie said, immediately disinterested. And Eliot couldn’t blame him. Falk kids weren’t from around here, as was clear as day from Eliot’s accent. They came, they stayed for four years or until they failed out, they terrorized the city with their wealth and temerity, and they left.

Eliot leaned his head against the window and waited for the river to turn into Forbes and Oakland. Or for the cab to crash and deposit them both into the Monongahela.

He didn’t feel any sense of homecoming as the cab pulled around Jessop and Eliot unloaded his bags. There was dull resentment and a tinge of hatred directed towards his father. No peace. No relief, even though he’d spent the last twelve hours traveling and this was his first time on steady ground with the promise of food, shelter, and Wi-Fi.

He tipped the cabbie more than he should’ve, both because he had the money and because the cabbie knew he had the money and didn’t expect Eliot to use it.

Eliot stowed his suitcase under a stairway—nobody was going to steal it, not in the English building, and especially not in the English building during the summer—and started towards Jessop. When he was halfway down the hall, a girl dashed out of the library, eyes on her watch, and stalked off down the stairs.

He stopped. Watched her go.

It wasn’t peculiar to see a girl in Jessop—after all, this was a school, and girls did go here. But it was unusual to see a girl he didn’t recognize.

Eliot had been going to Falk ever since he was a freshman; ever since he’d become less of a son and more of a bargaining tool. He knew every person from every class from the time he was fourteen until now. There were no strangers at Falk—but there she was. He watched her blond ponytail swing against her back as she ducked out the door and disappeared.

He didn’t know what to make of this. The girl was as unfamiliar as contentment, as unwelcome as a gunshot, and made him feel even more unbalanced.

If he could just get his hands on a book and his mind out of the present, he’d feel more cemented. Rubbing his temples, Eliot went into Jessop. He did know the girl behind the circulation desk, which was a welcome reassurance that he hadn’t been transported into an alternate universe. Her name was Rebecca or Rylie or something like that. She looked up when he came in.

“Hi,” she said, recognition lighting in her eyes. “Can I help you?”

Eliot shifted, unable to shake the sense of being a little unmoored, a little uneasy, as if the entire library had shifted and resettled in the week he’d been away. He wished his eye would stop twitching. “Do you have the offices assigned yet? For seniors?”

“Uh, yeah.” She slid down the desk and pulled out a clipboard. Eliot withered a little when he saw she wasn’t in her school uniform. It wasn’t that he cared what she wore, but it was another one of those little shifts that made this library unfamiliar. During the school year, everyone was so tidy: khaki pants and plaid skirts and pressed white shirts and sweaters and ties. He’d blend in, even in the non-uniform black jeans and shirt and cardigan he wore on the plane. But now he was overdressed in his own territory, a remnant from a not-so-distant past in the face of the girl’s modernity.

“You’re 354,” the girl said. She pulled a key out of one of the desk drawers, double-checked the number on it, and slid it over to him.

The key was heavy, solid, real. If only he felt the same way. “Do you know if my books are already upstairs? I requested some while I was away.”

The girl blinked at him, and for one stomach-flipping moment, he wondered if his requests hadn’t gone through. The sooner he could get to work, the sooner he’d feel better.

“One sec.” She grabbed a legal pad and squinted down at it. “Tess has some notes about a lot of faculty requests…” She trailed off, looking him over. Maybe even daring him to correct her.

Trying to remain smooth, Eliot said, “That’s me. I have faculty permissions for the summer.” It was a simplification. Students were only allowed to take out fifteen books at a time, but faculty had unlimited access. It had only taken a quick talk with the IT team and some gentle bribing to get the faculty permissions added to his computing account. Not that anyone needed to know that.

She seemed satisfied with his answer. After all, why would she doubt him? “Fair enough. Tess is halfway through pulling them. They’re in the cage.”

The locked cage he had no access to. All of this would be so much easier if he could pull his own books, but not even his father’s passcode or the IT team could get him into the stacks, which required a real key. And there was no way he’d convince the half-mummified pissant of a librarian, Ms. Matheson, to let him go off on his own.

“Is there any way I can get them tomorrow morning?” Eliot asked, keeping his voice smooth and neutral. He forced his eyes to relax, forced his lips into a smile. If there was anything of his father’s he needed to use, it was his charm.

It worked. The girl smiled back. “Yeah, of course. I can finish those today and have them in your office before I leave.”

“Thank you,” Eliot said, feeling his smile relax into a real grin. It meant he couldn’t start any of his work today, but maybe it would be best to go home and sleep off the jet lag and try to remember what contentment here was like.

And the conversation yielded another victory: the identity of the girl from the stairs. It only made sense that the girl he saw on the stairs was Tess. It didn’t erase the oddity of not knowing her, but at least he had a name to put to the face, and that made him feel like his kingdom was once more within his control.

Eliot retrieved his suitcase and left Jessop’s cool darkness behind. The streets were still sunny and awful, but he had a plan now. He’d call his mother—maybe call his mother, considering she might’ve been sleeping—and eat something that wasn’t served on an airplane, and then he’d ignore his phone when his father remembered Eliot was back on this side of the Atlantic.

And tomorrow, the fun would begin.

As Eliot walked to Dithridge, he turned over his requests in his head. They’d been unconventional, to the say the least; grimoires and books of magical history, things that other students would probably sneer at. And it was lucky he had the cover of a senior project—he was Eliot Birch. No matter what he wrote about, one of the English teachers would be happy to supervise. He could take all his work and turn it into something academic and worthy of study.

None of them needed to know that Eliot was not conducting his project for academic purposes, nor that this was a ritual of self-discovery. As he walked, Eliot ran through words, tasting the magic of them on his tongue: ita mnitim jusre, a spell for minor healing; kirra istra moine qua, one for basic tidying; mannitua critem mag, for a clearer head. Nothing happened with the words alone, but the shape of them was a comfort.

It was one thing to read about witchcraft. Learning to use it properly was another thing entirely. And this time, Eliot was on his own.

three

Tess

“This tastes like feet. Is it supposed to taste like feet?”

The spoon hovering in front of Tess’s nose did vaguely smell like feet. She glanced at Anna Liu, her roommate and closest friend, on the other side of the spoon.

“Believe it or not, footy soup is not the first thing I want to put in my mouth after work.”

“Sorry,” Anna said, pulling the spoon back and giving it an experimental lick. Her lips quirked into a frown. “We’re all out of dick.”

Tess rolled her eyes and pushed past her into the living room. The scent of whatever Anna was cooking had permeated the entire dorm. It only smelled marginally better than Tess, who’d spent the last six hours at Emiliano’s. There was a dining hall, open during regular hours for anyone left on campus, but it kind of sucked. Tess would have to risk the soup if she was hungry.

She threw herself down on the couch. In her room, her cello called to her, half-unpacked across her bed where she’d abandoned it. There was a concerto she needed to record, and she had to email her cello instructor, Alejandra, and the program director of the camp she usually attended over the summer to explain why she wouldn’t be going this year. There were a dozen other emails to send, Sorry I can’t attends and I’m afraid I won’t be able to play fors, things she’d been gradually canceling since she moved across the state months ago.

She also needed to call her parents, even though she dreaded the tense, silent, blame-filled conversations.

Asked: “Did Aunt Mathilde give you and your sister grocery money for the month?”

Unspoken: We’ll do our best to help, but we barely have enough for the bills.

Asked: “Did you talk to your sister today? Can you ask her to call us?”

Unspoken: It’s killing us to have you both so far away for so long. If this was up to us, we wouldn’t have chosen it. We would’ve figured something out.

Asked: “Have you had time to practice?”

Unspoken: I’m sorry. I love you. This isn’t what we wanted for you.

“You okay, buddy?” Anna asked, crashing down on the cushion next to her.

“Fine,” Tess said, leaning her head back and closing her eyes. She could fall asleep right here, shoes on her feet and apron still double-knotted around her waist.

“Anything happen at work?”

Tess opened one eye. “I’m going to kill Dr. Birch,” she announced. “He requested 147 books. I spent all morning in the stacks, and I only got through half.”

“Make Regina do it.”

“You know as well as I do that Regina doesn’t do anything.”

“Back to the first plan, then. Kill him.”

“I’m strongly considering it.”

“Well, it certainly wouldn’t make the school any more of a hellscape,” Anna said. The couch creaked as she got up and padded back to the kitchen. “Oh, hey. Package came. It’s on the table.”

If Tess didn’t get up, she was going to fall asleep like this, and there was far too much work to be done tonight to let that happen. She heaved herself up, ignoring the ache in her feet, and shuffled to the kitchen table.

The package was nondescript: a plain brown box the size of a toaster, the only label handwritten in gray ink. She picked it up immediately when she saw the return address was to the Matheson Pen Company. Her father. She hated how it made her stomach lurch with equal measures of anger and hope. Tess tore off the tape to reveal two bottles of ink and a slim navy box nestled among the bubble wrap.

She pulled out each item and set it on the table. Two inks, azure and deep amethyst. Inside the navy case was a new pen and a note from her father.

Tess,

I had a canceled order and thought you’d like the colors. Let me know what you think of the pen. New model. Nib feels dry to me.

Xoxo,

Dad

The letter was written on paper she recognized from the short-lived and disastrous Matheson Stationery, a brick-and-mortar extension of the pen company. Even the faintest reminder of the shop made her immediately angry. Tess crumpled the note into a ball and tossed it into the trash.

It was more likely that there was no canceled order, that her father had merely been thinking of her and put this together himself. Maybe it was a sign that he was trying. Which…okay, but it didn’t count for much.

Tess Matheson had sprouted out of a childhood drenched with ink.

Her father, owner of the Matheson Pen Company, taught her from an early age how to change nibs and fill cartridges until both of their hands seemed to be permanently lined with a rainbow of pigment. Her mother, a teacher, corrected papers in careful red and slashed through incorrectly spelled words with bold purple. Tess was watered by fuchsia and turquoise, nurtured by emerald and onyx.

Ink was malleable. It did what it was told, unless there was too much of it and it bled through the paper. But Tess was too good, by now, to let it bleed.

Unlike the internet, information on paper wasn’t forever. It could be burned, consumed, never seen again. Love letters could be forgotten. Secrets could be destroyed. Stains could be scrubbed away. Ink was not forever.

And neither were businesses, apparently.

But unfortunately for her parents, Tess’s grudges outlasted ink. She frowned and shoved the samples back in with the bubble wrap.

“Pretty,” Anna remarked, looking over Tess’s shoulder. Another relic of Falk, Anna would never fit into the scattered and messy life of the Matheson’s farmhouse. She was too perfect, too polished, too real instead of a smudged mixed of uncertainties. Anna reached down and touched the nib of the fountain pen. “Seems sharp. Could be a secret weapon. Birch would never see it coming.”

The idea satisfied Tess for only a moment. “I don’t think Aunt Mathilde would be too fond of me shanking someone in the library. Especially not Dr. Birch.”

Anna shrugged. “She’ll never know if you hide the body well.”

Tess rubbed her eyes. “Maybe,” she said, and she was so, so tired of it all.

“What did he request, anyway? It’s not like Jessop has math books.”

Tess wrinkled her nose. That was another oddity. Dr. Birch had a special focus on astrophysics or something else Tess herself could never bring herself to care about. “Occult books, actually. Grimoires.”

Anna snorted. “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Despite the dozen times she’d washed her hands since leaving Jessop, Tess could still feel the dust of the books pressed into the lines of her palms.

“Maybe he’s trying to put a spell on you. On us. To rid the world of scholarship students for good.”

Tess rolled her eyes. “He’s such an entitled dickhead.” She could spend all night here with Anna, complaining about Dr. Birch, but her cello called to her from her room, no matter how exhausted she was. “I’m going to go practice. Let me know if it’s too loud.”

She gathered her stuff and went to her room. Tess had an odd, fierce love for the upperclassmen dorms at Falk. They were set in converted rowhouses, with each floor housing two suites and a dorm sister. Anna and Tess technically shared the suite with two other girls, but since it was summer, their rooms were deserted and their doors were locked. Even the dorm sisters, as the college students who were paid to supervise the girls were called, were more relaxed than Tess had expected—and fairly nonexistent during the break, though she wasn’t sure if that was a result of loosened school policy or because the girl who was supposed to be watching over their accommodations was more interested in bar-hopping than in checking on the few residents who stayed for the summer.

When they first arrived, Tess was worried she and Nat would be sent to Mathilde’s home in Squirrel Hill, but her great aunt decided they would adjust better to Falk if they lived in the dormitories.

Living in the dorms had the added, unexpected perk of Anna. Tess and Anna were too self-contained on their own; they never would’ve gotten up the nerve to talk to one another and become friends if they hadn’t been forced into a living situation.

Tess loved the muffled noises of the other girls in the dorms during the school year, and the odd quiet during the summer. She even loved her bedroom, though it was more of a broom closet, with space for a bed and wardrobe and very little else.

The room looked even smaller due to the fact it was cluttered with assorted pens and inks, sheaves of sheet music, clothes, and books. Luckily, growing up the way she had, Tess wasn’t bothered by untidiness. She was most comfortable in a stable state of clutter.

Alone, she sat on her bed and flipped the new pen over and over in her hands. Tess rarely allowed herself to feel homesick. It was a weakness she couldn’t afford, not with everything else she was trying to keep in check. Besides, homesick wasn’t the best word for what she felt. She could go home, probably, but it wouldn’t be the same.

It wasn’t just home she missed. It was a mix of things: trusting her parents; practicing her cello whenever she wanted; not worrying about money; being able to breathe without feeling like the walls were falling in on her.

She flopped back and closed her eyes. There, on the slippery underside of her thoughts, was the ever-running mantra. Jessop at 10:00, sleep, cello, concerto for this weekend, but Jessop in the morning and Emiliano’s. Work, sleep, did you talk to Nat?, sleep, don’t sleep, you need to practice, you need to practice, you need to practice.

Sleep.

Don’t sleep.

Don’t think of home, don’t think of home, don’t think of home.

You’ll never become anything if you just lay there, if you don’t practice.

You’ll never become anything.

Tess opened her eyes and glanced at her clock. It was late, both too late and not late enough to make excuses. Though every muscle ached, she got up and retrieved her cello. As the rest of the city quieted down and settled into sleep, Tess pushed aside her crowding thoughts, raised her bow, and began to play.

Nothing, she thought with each down-bow. You will become nothing. With every up-bow, she tried to fight it, tried to remind herself how far she had come and how far she could go. But in the end, it was nothing, nothing, nothing, until every stroke dissolved into discord.

four

Tess

Thursday was Regina’s day to open the library alone, so Tess went in at 10:00. She would’ve killed for five more minutes of sleep, and the sky outside was just as gray as her mood. To make matters worse, Regina started talking as soon as Tess was through the doors of the library.

It wasn’t that she hated Regina. Tess’s feelings towards Regina were similar to her feelings towards small dogs. Both were fine enough, but rather useless, and made far too much noise.

“But anyways,” Regina said, finishing a story about some senior Tess didn’t know. “I finished that big request and delivered the books for you.”

That for you was enough to get Tess’s attention, since it implied both that Regina was doing Tess a favor and that she didn’t believe doing work was her actual job, but the rest of the sentence sent Tess’s heart hammering. Her eyes snapped away from her laptop screen to Regina’s face. She looked too helpful, and there was something cruel in her eyes.

“What books?” Tess asked, fearing the answer.

“The ones in the first-floor cage. I put them in Eliot’s office.”

As Regina prattled on, a vein of icy dread opened in Tess’s brain and leached throughout her body. Part of her thought it was odd that Regina was calling Dr. Birch “Eliot,” as if they were friends, but then again, it was like Regina (and most of the students at Falk, really) to suck up like that. But worse: All those sticky notes. All those insults.

“Did you, uh, happen to take the sticky notes off of the covers?” Tess asked.

Regina blinked at her for a second. “No…should I have?” Tess would’ve thought Regina was innocent if she hadn’t caught the smirk at the end of the question.

Regina knew exactly what she was doing.

Tess swore and pushed away from the desk. “I have to go… Are they in his office?”

“Yeah,” Regina said, “but he already came in and grabbed some of them, and I think he locked the door.”

What, was Regina just camped outside Dr. Birch’s office? Either way, this was bad. Very, very bad. There was no way to get those books back now. Tess’s face glowed hot with shame.

Maybe he hadn’t seen them yet, but he was going to. And Tess doubted very highly he would keep his mouth shut about it, especially since he had already decided to hate her.

But there were still books to shelve, and Tess found she wasn’t past hiding in the stacks for the rest of the day. Perhaps the rest of the year, if it meant avoiding Dr. Birch entirely.

“Okay,” Tess said, fumbling for her headphones. “I’m going to, uh, finish up that stack of books. Let me know if you need anything.”

Regina only smiled. Tess wanted to punch her.

Tess’s crisis continued past Mathilde’s office, down the stairs, and into the cage. I could lose my job for this, Tess thought. Or, even worse than losing her job: she could make her great aunt regret she’d ever gotten Tess into Falk in the first place.

After all Mathilde did for them, this was how Tess paid her back. Hot shame curled in her veins.

Maybe he wouldn’t notice. Or maybe he wouldn’t know it was her. For one piercing second, she considered pinning it on Regina, but she immediately knew she couldn’t do that.

One thing was certain, though: She had no idea how Dr. Birch would react. And until then, she could only wait.

Though they were creepy, Tess felt oddly comfortable in the stacks. The smell of paper, the loneliness of it, reminded her of her father’s short-lived shop.

When her father had owned the shop, Tess spent weekends there when she didn’t have gigs to play. It was her favorite thing, to curl up in the beaten window seat and read or listen to music. She loved the stationery shop with a deep, intrinsic part of her, the same way she loved her cello. And more than anything, it symbolized so much for her dad: his own dream come true.

Tess reached the bottom cage and rested her forehead against one of the shelves. She curled her fingers against the cold metal, rubbing her thumb against the leather binding of one of the grimoires. She breathed in deep, taking in the dust and paper and ink, the horribly unsettling feeling of being isolated underground, the awareness of just how alone she truly was.

Maybe she liked it in the stacks because these books were set aside and forgotten. They meant nothing to anybody, and yet they continued to exist.

five

Eliot

Eliot was feeling significantly better by the time he made it to Jessop. He’d had nearly twelve hours of sleep and successfully managed to avoid his father for the entire time he’d been back on American soil. The sky was back to dismal clouds, which was a relief, and he knew when he eventually got to his new office in Jessop, there’d be books inside.

Things were looking up.

He walked to Falk as the first drizzle of the morning broke through the clouds. He had an umbrella but chose not to use it, welcoming the fat, lazy drops splattering the shoulders of his sweater and dampening his hair.

He’d always been partial to rain. Anytime it rained when he was younger, his mother, Caroline, would wait until his father went to work and then pull Eliot out into the garden. She’d turn the music on loud in the house, and the sound would float out to them. She would take one of her tinctures and charm them both to be water repellant. They’d dance and spin and fling water droplets off leaves at one another. They’d hide in the dry place beneath the willow, still shimmering with the tingle of magic, and listen to the pattering drizzle mix with the drums of whatever song she put on. Under the willow in the rain, they’d talk about magic. Those were the times he liked best.

The R-named girl (bloody hell, he really had to do a better job remembering people’s names, it made him seem unobservant) was in Jessop again when he entered, staring at her phone, book unread and pushed to one side.

“Good morning,” Eliot said to her, and she flashed him a smile that was too perfect for spontaneity.

“Good morning,” the girl said. “I finished those books and put them in your office.”

“Ah, wonderful. Thank you.”

“Of course.” The girl paused, and Eliot had the weighted feeling she wanted to say more, so he pretended to examine a flyer at one end of the desk while she decided whether to keep speaking. “I didn’t know that Tess disliked you so much.”

Eliot frowned. “I’m not sure what you’re talking about. Who is Tess?” He had an idea of who she was—the specter on the stairs yesterday—but that wasn’t enough of an explanation.

“Tess Matheson? She works here?” The girl must not’ve seen the recognition she was looking for in Eliot’s eyes, because she continued, “She’s Ms. Matheson’s niece. She moved here, like, right after spring break with her sister. You know, she’s that prodigy cellist or whatever?”

This story sounded familiar, but Eliot couldn’t pick apart the details. Spring break was rough for him; he’d gone back home, only to find his mother was doing worse, and then he had to come back so quickly after. He’d spent the rest of the spring semester in a haze of anxiety, worrying that each buzz of his phone would be a call from his mother’s caretaker. It was no wonder he hadn’t been involved in the gossip when Tess and her unnamed sister arrived with the spring sunshine.

“Why don’t you think she likes me?” Eliot asked.

“The notes,” she said. “You’ll see them.”

Eliot waited for clarification, but the girl went right back to her phone. He climbed the stairs to the third floor and unlocked the door to his office.

There were floor-to-ceiling bookshelves on one side, already stocked with anthologies and dictionaries and ethnographies that Eliot would have to pick through later. A huge desk and comfy chair stood in front of a window that looked out over campus. And there, next to the radiator, were two carts full of books.

It was everything Eliot wanted.

He set down his bag and ran a hand over the wood of the desk. It was smooth, polished by years of use.

Not even being in Pittsburgh could crush his spirits now.

The first order of business was unpacking. Eliot fumbled through his bag, awkwardly heavy with his trove: a bone he’d managed to take from a forgotten crypt in the English countryside; a variety of crystals acquired both from his mother’s collections and shops around the world; small vials of dirt from Hyde Park and Frick Park and the Himalayas and a handful of other places; a feather from a crow; three scales from a long-dead viper; a collection of other bits and bobs that would hold no significance to anyone else, but to Eliot were sources of power. Carefully, he unwrapped the leather-bound notebooks of his mother’s spells and notations she’d written over the years. Though Jessop was full of grimoires, none were as precious to him as these.

If only they held the answers he needed.

He sat down at his desk and reached back for a book. It didn’t matter which one—they were all important; they’d all come across his desk at some point. He had the pleasant sense of focus that came with the beginning of a job, that signified there was work to be done and one way or another, he would accomplish it.

There was something there, on the cover of the book. A Post-it note. Yellow against the black cover, teal writing boldly slashed across it in a slanted, uneven cursive.

Eliot Birch is a bland, wrinkled, crap-coated mailbox flag.

He read it once, then again. It didn’t make sense for a few reasons. First and foremost, he was not bland. When he was actually trying, Eliot thought he was quite an interesting person.

He also wasn’t wrinkled. After all, Eliot was only seventeen. He had none of his father’s worried creases or his mother’s laugh lines.

And lastly, what was a crap-coated mailbox flag? He didn’t understand.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed the other yellow squares. They were all over the first cart of books, written in the same hand, inked in the same teal color. He pulled them all off, scanning them, tossing them to the ground. By the time he reached the last of them, the notes blanketed the carpet around him like crisp autumn leaves.

Who even had the time to insult him this much?

And who cared about Eliot enough to write what had to be dozens of sticky notes about the finer points of his breeding?

Tess Matheson. That was her name—the girl who’d done this. Who had some sort of problem with him. If only he had any idea what that problem was.

Eliot sat down heavily. Something that bothered him more than any of the questions was how he felt. Because Eliot, who’d spent enough of his time with horrible, angry, malicious people, never considered himself to be one of them.

The puzzle of his thoughts was a constant nuisance into the afternoon. He tried to do work, to pull the grimoires and scan the contents, to check the spells, but he kept getting distracted by some new turn of phrase that stamped the sticky notes near his feet. He stared down at his hands. His mother’s wedding ring was around his pinky; he usually twisted it when he was upset or anxious, but he couldn’t bring himself to touch it now. It was like the metal was conductive, and touching it now would transfer all of those bad things someone had written about him straight to his mother’s brain.

He had to know why Tess hated him, and he was going straight to the source. Eliot got up and shuffled through the sea of Post-its, back to the door. He peeked out over the reading room. The girl’s dark hair from this morning was gone, replaced by blondish-brown that he recognized from the staircase.

Tess.

He stepped back to compose himself. Eliot straightened his tie and pulled at his sweater, making sure his shirt was fully tucked underneath. His father never taught him much, but he did beat one thing into Eliot: when cornered, it was imperative to remain as charming as possible. Eliot ran his fingers through his hair, taming the dark curls, and pulled out an award-winning smile from his back pocket, slipping it on like sunglasses to disguise the thunderstorm in his eyes. Tess Matheson had no idea who she’d decided to battle.

six

Tess

But really, Tess Matheson had no idea who she’d decided to battle.

She’d hidden in the stacks, shelving books for nearly an hour before Regina summoned her to watch the desk while she went on lunch break. It was absolutely the last place Tess wanted to be, but the rules required someone to be within shouting distance of the reading room at all times, and Mathilde had some sort of meeting about funding.

So Tess sorted through her email and studiously thought of anything other than Dr. Birch. She had a few requests for private engagements in her inbox, forwarded from Alejandra. It was something she was trying. Except the first one was a wedding offering to pay in “exposure :)” so Tess shut her laptop and dragged out a book instead.

It was ten minutes past the time Regina should’ve been back when the boy walked out of one of the upstairs offices. He surprised Tess for three reasons: first, because nobody came into Jessop during the summer and second, when they did, they were almost always curmudgeonly old men either looking for the bathroom or there to recount tales of Falk’s glory days, back when it was an all-boys school. This boy did not fit into that category. And third, because she’d thought she was alone. The unexpectedness of his appearance set her on edge immediately.

He looked to be about her age, with a navy sweater over a collared shirt and a smartly patterned yellow tie. He had the kind of nose Tess’s mother would’ve called stately and dark brown eyes Nat would’ve cut from a magazine and pasted into one of her “Painting Inspiration” scrapbooks, which she kept because she was too hipster to have a Pinterest. His curly hair was arranged like he’d tried to tame it a few times and had been only marginally successful. In short, he looked like he’d stumbled into Jessop on accident—or, maybe more fittingly, like he was meant to be in Jessop when it was something else, when it wasn’t just summer and no students were here.

“Hello,” the boy said, striding across to the circulation desk. “Are you Tess?”

She felt disarmed. She’d never seen this boy before, she was sure—or had she? Her first couple of months at Jessop were a blur of faces, mostly sophomores that shared her classes. The longer she looked at him, the more uncertain she became. There was something in the twist of his mouth, the glint of his eyes, that looked familiar, but out of place on his face.

“I am,” she said.

“I think you and I need to have a chat,” he said. His voice was pleasant, kind, and distinctly British. Falk did have a variety of international students, but it wasn’t often she encountered accents like his in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In fact, Dr. Birch was the only Brit she could recall running into at Falk.

“Sure. How can I help you?”

“I’m missing some books I requested,” he said, and his voice was a little more clipped, his eyes harder. Over the collar of his shirt, his neck was bright red.

Something was not right here.

“What name are they under?” Tess asked, voice thin. She hated the fact she thought he was attractive even though he was rude, hated that he was acting like every other Falk boy she’d had the misfortune of talking to.

“They could be under lazy douche canoe or witch-hunting fuckface. I would suspect either.”

Oh.

Oh no.

Tess looked up at him. The boy’s dark eyes were cool as he appraised her. Now, she saw, he had a crumpled ball of yellow notes in his left hand, with a curl of California Teal ink in her own handwriting.

There was nothing she could say. By the look on his face, she knew the rush of blood to her cheeks proved her guilt.

But who