5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

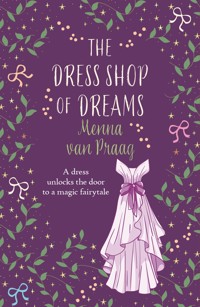

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Magical Cambridge

- Sprache: Englisch

Every dress unlocks the door to a magical fairytale Etta's tiny dress shop stands on a seemingly ordinaryCambridge street, but the vibrant racks of beaded silks and jewel-toned velvets possess a bewitching power to awaken a woman's deepest desires. Etta's granddaughter, Cora Sparks, has spent her life sheltered in the shop and her university lab, avoiding the mystery of her parents' deaths and overlooking her secret admirer, Walt, a man with a magical voice. Determined to change Cora's fate, Etta weaves a plan that sparks a series of extraordinary events, transforming Cora's life in astonishing ways. 'Sure to delight those looking for a little fairy dust in their romance' KIRKUS REVIEWS Readers adore Menna van Praag: 'This little book was such a delight to lose yourself into' 'Once I begun I was hooked and found I couldn't wait to find a spare five minutes to continue reading' 'A beautifully crafted book' 'Couldn't wait to pick it up at every opportunity'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Dress Shop of Dreams

MENNA VANPRAAG

For Mum, with infinite love

Contents

Chapter One

When ordinary shoppers stumble into the little dress shop, they usually leave without buying anything. Nothing seems to fit or suit them very well. The music clouds their chatter and the shimmering silk walls hurt their eyes. After a few minutes they stumble out onto the street again, muttering to their friends about fashion and wondering why they ever bothered to step inside in the first place. But when a different kind of shopper discovers the shop, they find that opening its little blue door is the very best decision they’ve ever made. These are the women who aren’t really looking for the perfect cocktail dress, the jeans that’ll lengthen their legs or the skirt that will slim their silhouette. No, these women are looking for much more than that; they are looking for a lost piece of themselves. Which is exactly what Etta Sparks can give them.

When such a woman absently ruffles through the racks of expectant dresses, casting furtive glances towards the counter, Etta sits pretending not to notice, until the time is right. Although she isn’t actually psychic (being able to see only what the dresses show her) Etta has many gifts, and one of them is knowing when someone is ripe. She can see when a shy woman is on the edge of feeling brave. And then she steps forward.

‘That would look beautiful on you,’ she’ll suggest gently. ‘Why don’t you try it on?’

They always shake their heads at first, of course. But Etta can see the desire in their fingertips, the tiny flicker of hope in their eyes. So she chats about anything: the weather, the music, the sweetness of strawberries, the latest film, a particular book, the sensuality of silk … Then, when the woman is ready, Etta picks out a dress – in their favourite colour, one that will make their eyes sparkle, their hair shine and their skin glow. And, now that she knows their greatest wish, Etta makes them a promise. A promise she knows to be true.

‘Wear this dress and you’ll find what you’re missing: confidence, courage, power, love, beauty, magnificence …’ Etta says, while they regard her rather sceptically. ‘You will. I promise. Wear this dress and it will transform your life.’

Etta doesn’t mention that it might be a bit of a bumpy ride, at least at first. When a woman needs courage, for example, life might throw a few things at her to draw it out. When a woman needs to love herself, she might be lonely while life leaves her without external hearts to hide in. Other things are simpler, like beauty and magnificence, since as soon as a woman slips the dress over her head and stares into the mirror, she instantly feels more beautiful and magnificent than she’s ever felt in her life.

Fortunately there is nothing that, with a little nip, tuck and the stitching of a special little star, Etta’s dresses can’t provide. For these are dresses that unlock the wisdom and wishes of women’s hearts, dresses that help them to heal themselves and, eventually, attain their deepest desires.

Etta loves to watch when these women step out of the changing room, their faces lit with delight and disbelief.

‘My goodness,’ they say. ‘But it’s so … I look so, so …’

‘Beautiful.’ Etta nods. ‘Yes, you do.’ And she watches them, swallowing a happy sigh and everything else she wants to say but really shouldn’t.

‘You just need a nip here,’ she says, taking a threaded needle from her pocket and making six quick stitches in the shape of a star, ‘a tiny tuck here. And voila!’ Etta steps back, a knowing smile on her lips and a sparkle in her eye. ‘You are perfect.’

It happens the same way every time. The woman usually stands in front of the mirror for a while, turning this way and that, checking to be certain it isn’t an illusion. And, when she is at last sure it’s real, a blissful smile spreads into her cheeks and flushes through her whole body. In the mirror she sees herself as she truly is: beautiful, powerful, able to do anything. And she sees that the thing she wants most of all, the thing that seemed so impossible when she first stepped into the little dress shop, is really so possible, so close, that she could reach out and touch it.

‘Yes,’ Etta says then, ‘as easy as pie. Speaking of which, the bookshop on the corner does the most delicious cherry pie. You really should try some.’

The woman nods then, still slightly stunned, and agrees, saying that pie sounds like a perfect idea. So she stumbles out of the shop in a daze, new dress tucked tightly in her arms, and wanders down All Saints’ Passage to the bookshop. There, she has the best piece of cherry pie she’s ever eaten and leaves with a stack of books that will make the transformation complete.

Cora blinks. She yawns and stretches, then rubs her eyes and gazes up at the ceiling. 564 fleurs-de-lis gaze back down at her. As her body wakes, she could swear faint echoes of jazz drift away and fireworks still sound in the distance. It’s that dream again. The one so vivid it feels more real to her than reality. The one she’s been having nearly every night of her life. The only one she remembers every morning when she wakes up.

In her dream Cora is standing at her bedroom window, tiny hands splayed on either side of her freckled nose against the glass, watching fireworks explode, scattering light like fistfuls of stars. Down in the garden a hundred lanterns hang above a hundred heads, luminous rainbows of silk bobbing along to the jazz. Champagne corks pop and trumpets blow into the air amid claps and cheers. A beautiful black woman sings on stage, her voice as bright as the feathers in her hair.

Cora sees her parents standing close to the singer, sharing a glass of bubbling, sparkling water. They sway together, her father’s arm around her mother’s waist, her beautiful head tucked against his chest. Cora wants to join them. She wants to sing, dance, clap and cheer. She wants to freeze-frame the fireworks and count each burst of light. She wants to open her mouth and swallow the sparks and stars as they fall from the sky. But Cora is too young for the party. She was sent to bed hours ago and really should be asleep. Instead she watches the celebrations, listening to the laughter and the jazz tapping on her window, until the last firework explodes and the moon fades away in the milky dawn.

Cora would swear it was a memory, but she understands it can’t be. Her parents died twenty years ago today, on her fifth birthday, and she only knows their matching black hair and green eyes, their tall gangly figures and faraway stares, from photographs. There was never a party, and certainly not such an extravagant affair, of this Cora is certain. Her parents were prominent academics at New College, Oxford, who never frequented frivolous events. Maggie and Robert Carraway spent most of their days, and many of their nights, in the biochemistry department. When they weren’t cross-pollinating plants, discovering new species or generally trying to save the planet, Cora’s parents were teaching her the basics of complex tissues, encouraging her to experiment on sunflowers or taking her on tours of English woodlands, European mountains and African deserts. They usually forgot birthdays, anniversaries and the like. They would have forgotten Christmas, too, if the luminous trees and light displays throughout the city hadn’t reminded them. Not that they were neglectful, far from it. They simply lived in their own world – a world of cells and organisms, of ecosystems and genetics, of research and theories, but a world in which their daughter was at the very centre. The Carraways took Cora everywhere. They kept a cot in the biochemistry lab for when they worked late. She took trips to European conferences. She ate all her meals in the university canteen. She played with papers, pencils and chemical equations. A year before they died they published a letter in The Times calling for the government to fund research into sustainable foods capable of growing in barren climates to feed and sustain starving communities. The letter hinted that they were focused on creating such foods, but since all their papers burnt in the fire that killed them, Cora never knew for certain.

All of this early history has been recounted to Cora by her grandmother, since Cora doesn’t remember a day of it, having suppressed the memory of her life with her parents along with their deaths. As a child Cora asked questions about them all the time and Etta gave her carefully selected stories in return. Nowadays Cora tries not to ask too often, not to focus on impossible fantasy and lost hope, though of course she can’t stop the dreams. But the one thing she holds true to is that letter (Etta’s copy, framed on Cora’s bedroom wall) for it reminds her of why she does what she does, spending every day in the lab trying to fulfil her parents’ legacy, to do a great thing that would make them proud.

Cora slides out of bed and crosses her room, counting the floorboards as she steps across her tiny flat on Silver Street, provided virtually rent-free by the university in return for her devotion to their biology department. And so, for forty hours in the lab and twenty hours teaching each week, Cora has fifty-three square metres in the centre of Cambridge in which to sleep and eat. Not that she does much of either there. The flat is simple and sparse. The floors are wooden, the walls white. She owns no TV, no stereo, no ornaments. She never buys flowers or bowls of fruit. If Cora ever had visitors, they’d think she had only just moved in. If there was a fire the first, and only, thing she’d bother saving is her laptop. No paintings or photographs adorn the walls, no books are on the shelves. Everything she needs for work she has at her rooms in Trinity College. She survives on sandwiches and snacks from coffee shops at lunchtime, and vending machines late into the night, while she’s scouring over plant plasma and peptides.

The only bright and beautiful thing in Cora’s flat are her pyjamas: Indian shot silk, the colour of a sunset, sprinkled with 34 pink peonies and 69 blue morpho butterflies. She trundles into the kitchen now, opens the fridge and pulls out a bag of coffee beans. She weighs the bag in her hand – 1,233 beans, approximately. These, along with a week-old loaf of bread, are the only edibles in her flat.

Cora switches on the kettle, marking the seconds until it boils. Whenever Cora is worried – about life, science, loneliness – counting soothes her. She’s always had an extraordinary ability to count, to just know facts and figures at a glance. Of course, to her it’s perfectly ordinary, since she’s always been able to do it. But she understands that other people can’t and that those same people might find her strange, so she tries to do it only in private. While sixty-seven seconds tick by, Cora imagines her day. In an hour she’ll be at the lab. Three hours and fifty-five minutes after that she’ll eat lunch. Or, more likely, forget to eat lunch. Six hours and twenty minutes after that she’ll nod at her colleagues when they leave for the day. Three hours and forty-seven minutes later she’ll leave. Then she’ll come home and go to bed. Three days a week she adjusts the schedule for an evening visit to a bookshop. Within that she fits in her teaching commitments and visits to Etta. Otherwise, her days all follow the same pattern: yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Then, as she pours the hot water into the French press, Cora remembers the date. March 14th. Which means that today is a bit different; today she’s having dinner with her grandmother. Today is her birthday.

Chapter Two

Even though Cora must have stepped into her grandmother’s shop twenty thousand times, she usually walks past the little blue door and the window draped in dresses. If she’s lost in thought, counting the cobbles on the street or the bricks on the walls, then it only takes a second before she’s back onto the main street and has to turn around again.

Apart from A Stitch in Time, there’s one other shop on All Saints’ Passage that Cora frequents – a bookshop, with a little red door and a little window crammed full of fiction – a rotating stock of 983 volumes. Inside, both places are much bigger than it seems possible they could be. Bigger than Cora’s flat; not big enough to get lost in but big enough to hide in (which she does three times a week), if no one was particularly intent on finding you. She has known the owner, Walt, since she was a girl. Apart from her grandmother, he’s her closest friend, and if Cora was interested in romance she’d be interested in him. However, since she isn’t, she hardly gives him a second thought.

No matter how many times she’s done it, every time Cora walks into the dress shop she gets a jolt of surprise. Stepping through the door is like stepping back in time. 1,349 (at her last count) dresses in every style hang on racks, clustered together as if holding hands and gossiping among themselves. Sequins flash from sleeves, sparkling beads swish from hems, and every colour that one could possibly imagine (and a good number that one couldn’t) shimmer and twinkle like galaxies of stars bottled in jars. Rows of shoes sit on shelves above the clothes, dyed every hue and tone, each pair a perfect match to one of the dresses beneath. The walls are wrapped in silk, the floor carpeted in velvet, the colours changing according to the shifting seasons.

Music is the breath of the shop, though Cora has never seen a record player. Music – from Stravinsky to Sinatra – plays every moment of the day and night, gentle and low when the shop is empty but quickening whenever the bell above the door chimes and someone new steps inside. Then the tinkling piano riffs speed into double time joined by wild saxophones, trumpets and beating drums. Perry Como, Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Waller sing and shout, their voices leaping and jumping, bouncing off walls and sweeping through the air so each new customer glides like Ginger Rogers off the street and into the shop. Cora has seen dowdy women with grey faces and buttoned-up shirts skip across the floor, their faces suddenly lit with shock and delight. Even Cora, who’s never danced a step in her life, sometimes catches her disobedient hips swaying to the beat of ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’ or ‘It Don’t Mean a Thing.’

Tonight Cora dawdles along the tiny, tight passage, counting as she goes: 86 leaves on the ivy inching up the wall, its vines concealing 28 bricks. She doubles back after missing the little blue door. The shop greets Cora with ‘One O’Clock Jump’ as she rushes past curtains of clothes to arrive in the sewing room, tucked away behind the counter, where her grandmother sits with a skirt of crimson silk on her lap. It’s the same shade the walls turn on December 7th until the twelfth day of Christmas when they sparkle bright white, the colour of fresh fallen snow. Now the walls are green-blue silk, for early spring.

‘Happy birthday,’ Etta says, giving her granddaughter a kiss. ‘And you’re still late, as usual. I suppose the life cycles of amoebas are far more fascinating than your boring old grandmother.’

‘Of course not.’ Cora smiles. This is how it goes every time, this is the routine between them. Etta has no idea what her granddaughter spends her days doing, no matter how many times Cora has tried to explain. ‘You aren’t old or boring. Life would probably be a lot easier if you were.’

‘Pish-posh.’ Etta gives a dismissive wave as she stands, dropping the silk skirt onto her sewing table. The room where Etta works her magic, mending and altering the clothes she sells, is even more chaotic than the shop itself. Hundreds of ribbons and threads hang from hooks on the walls, swathes of fabrics are piled up on shelves, open drawers overflow with buttons and beads of thousands of different shapes and sizes: 3,987, to be exact. It is an Aladdin’s cave of couture.

‘How do you find anything in here?’ Cora asks, yet again. ‘I’d go crazy.’ Her lab, home and office are all obsessively well ordered, everything in its never-changing place.

‘I don’t need to know where anything is.’ Etta shrugs. ‘Whatever I need finds me. It’s as simple as that.’

Cora frowns at her grandmother. She has never been able to make sense of her. Not since she was a girl. They are polar opposites. Where Etta loves flamboyance and frippery, colour and chaos, Cora likes everything in life to be structured and simple, plain and predictable. She prefers even numbers over odd. She likes to know what’s going to happen next, or at least be able to estimate the probabilities. Etta had long ago tried to sprinkle some frivolity into her granddaughter’s life, telling her that little girls were meant to have fun. She bought Cora silly toys, organised treasure hunts and Alice in Wonderland-themed tea parties. She turned a corner of the shop into a playroom where they could dress up together and dance to the Charleston with feathers in their hair. But it was no use. Cora went along with it all, dutifully smiling whenever her grandmother asked if she was having a good time. But her heart was never in it. After her parents died her heart was never really in anything again.

‘I know this is the only time you ever eat properly.’ Etta clears space on the table and produces two plates of roast chicken salad. ‘I’m going to wait until you eat every bite. We’re having cherry pie for pudding. Walt’s bringing it over later. I would have baked a cake, but I know how much you love his cherry pie.’ As she says this, Etta gives her granddaughter a sideways smile.

Cora frowns. ‘What?’

‘Nothing,’ Etta says. ‘Then we’re having cheese and biscuits after that; I’ve a rather delicious-looking Barkham Blue I’ve been saving for the occasion.’

Cora resists the urge to raise her eyebrows. ‘It’s only a birthday,’ she says. ‘It’s not a reason to celebrate.’

Why not? Etta is about to say, but she holds back because, of course, they both know the answer to that. As they sit down the bell in the shop tinkles and Etta jumps up from the table.

‘That’ll be our pie.’

Cora eyes her grandmother suspiciously as she hurries out of the sewing room and on to the shop floor. A moment later she is back, bustling through the doorway, one hand wrapped around the elbow of a tall, thin man dressed in blue jeans and a white shirt, whose messy black hair falls over his eyes but doesn’t conceal his large, but handsome, nose.

‘Hi, Walt,’ Cora says.

He nods in return and, with a sizeable nudge from Etta, stumbles forward into the room. He hands a plate of cherry pie to Cora and steps back.

‘Happy birthday,’ he says, his eyes fixed on the plate. ‘I made it twice as sweet, and with ground almonds instead of flour.’

‘Thank you,’ Cora says. ‘It smells delicious.’

‘I only took it out of the oven twenty minutes ago.’ Walt lingers a moment then steps back towards the doorway. Etta grabs his arm as he passes her.

‘Stay for some,’ she says. ‘It’d be wrong to eat it without you.’

Walt glances at the food on the table. ‘No,’ he says, ‘you’re still eating, I—’

‘Nonsense, it doesn’t matter, we’re nearly done.’

Walt hesitates then shakes his head. ‘No, I’d better go. I, um … like to do a stock check on Thursdays and it’s getting late.’

As Walt disappears, Etta throws a look of frustration in her granddaughter’s direction, but Cora just returns it blankly. Etta turns and hurries after him. She stops Walt as he reaches the door. The dresses displayed in the window rustle as if a breeze had just blown through them.

‘Wait,’ Etta says and he turns, fixing his gaze just above her head. ‘You know, some people don’t see the things right under their noses. They mistake the everyday for what’s ordinary and unimportant.’

Walt glances down at the tiny woman and meets her gaze, seeing the acknowledgment and affection in her watery blue eyes.

‘Especially those people searching for something,’ Etta continues. ‘They don’t know exactly what they’re looking for, but they always imagine it’ll be far away and hard to find. They think it’ll come with whistles and bells. Those people need shaking up to see something as simple as’ – Etta dropped her voice to a whisper – ‘true love with someone they’ve known forever.’

Wide-eyed, Walt shakes his head. The thought of him shaking Cora up makes him slightly sick with nerves. ‘I don’t really know what you …’ he begins. ‘Anyway, I’ve got to go. Enjoy the pie.’

Walt turns the wooden doorknob but Etta is too quick. She grabs the back of his shirt and holds on.

‘You’ve got a loose thread, just let me fix it for you.’

‘Don’t worry.’ He pulls away. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘It’ll only take a moment,’ Etta says as she plucks her special needle from her pocket. ‘Wait.’

Since he has little choice in the matter, Walt waits. Less than a minute later he leaves with a tiny red star stitched into the lining of his shirt.

When her daughter and son-in-law died, Etta was the first and only family member on the scene. She rushed to the hospital, scooped her sobbing (but otherwise unscathed) granddaughter up in her arms and promised the little girl that she’d protect her forever, that she’d never suffer again. And so, when it became clear that – as some sort of subconscious coping mechanism – Cora had suppressed all memories of her parents, happy and sad, Etta let it be. She allowed her granddaughter’s heart to remain shut down even as she grew older. But now she realises it must stop, or the cost will come at too high a price.

Etta’s always been aware that the numbing of Cora’s heart has suppressed her urge for laughter and desire for love as well as protecting her from pain. Most of all it’s left Cora oblivious to him. Of course, it didn’t matter while Cora was younger. Etta knew Walt would wait then, but he won’t be able to wait forever. Eventually, he’ll give up. And Etta can’t let that happen. If Cora doesn’t have the chance to love the man who loves her more than anything else, it would be a tragedy, a loss on a par with Etta’s own: the man she thinks about late at night with a bottle of bourbon and a box of chocolates. Fifty years ago, when Etta lost him, she still hoped life might be full of other lovers. And it was – just none who held her heart the way he did. Now Etta knows that great love only comes once in a lifetime, if you’re lucky.

Etta stands at the bathroom sink, looking into the mirror. Cora is downstairs, doing the washing-up. Etta turned sixty-nine two months ago, but she doesn’t look a day over sixty-one. Which is some comfort, she supposes, but not much. Every day she sees a new wrinkle in the mirror, another line etched on her once beautiful face. She pulls the sagging skin back from her eyes, stretching it almost taut again, consoling herself that the one advantage of her fading sight is she can’t see her fading face so sharply. Her granddaughter insists that she’s still beautiful, but Etta knows she’s not. Cora only thinks that because she loves her; she’s blinded to the depressing truth by sentimental feelings. But Etta doesn’t suffer under such illusions.

She hasn’t been with a man since her husband passed away twenty years ago, the same year her daughter died. If she hadn’t had Cora, Etta would have given up on life herself. While she was in her fifties, even in her early sixties, Etta still harboured hopes that she’d experience intimacy again, that one day she’d be held tight in a masculine embrace. But she knows it probably won’t happen again, not now.

Cora and Etta sit on the sofa in the living room halfway through watching Gone With the Wind. Etta gazes at the screen while Cora fidgets.

‘You know we’ve watched this film twenty-eight times before, don’t you?’

‘Hush,’ Etta hisses, ‘we have not.’

‘We have. And it’s 298 minutes long. That’s 111 hours. That’s four and a half days of our lives in the Deep South.’

Etta smiles. ‘And every minute very well spent.’

‘You’re obsessed with Clark Gable.’

‘Well, there’s nothing wrong with that. A girl could do a lot worse than Gable.’

Cora smiles. ‘You know he’s dead, right?’

‘I’m old,’ Etta says, ‘not senile. And, at my age, one has to take what one can get. Unlike you, who could be with a real flesh-and-blood man instead of her grandmother on her birthday night.’

‘I’m perfectly happy as I am.’

‘Are you?’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘Very well.’ Etta shrugs. ‘If you insist.’

‘I do.’

‘Then there’s not much I can do about that,’ Etta says. It’s a lie, of course. Etta has rather powerful means at her disposal, methods she uses every day to transform the women who venture into her little shop, but she’s been putting off using them on her granddaughter, hoping that it might happen naturally instead. As the years pass, however, Etta’s hopes have dwindled, which is why, tonight, she’s pinning them on Walt instead.

She hopes that her pep talk with Walt may have had some effect. Perhaps, for the first time, he’ll stop waiting in vain for Cora to notice him and do something to seize her attention instead. Etta doesn’t hold out much hope, since she must have given him a hundred similar nudges over the years and he’s never found the courage to act on them. Of course, this time is different, for this time he has a little red star stitched into the lining of his shirt to help him along. If that doesn’t work, nothing will, and then it’ll be time for Etta to take matters into her own hands.

Chapter Three

Walt has loved her forever, for nearly as long as he’s been alive. He was four years old the first time he saw her. It’s his earliest memory. A simple, ordinary day, made special and extraordinary by first love and first words.

Walt’s father had been shopping with his son on a Sunday afternoon when he’d wandered into All Saints’ Passage and found the bookshop. A silent boy, Walt still hadn’t spoken, so there was no reason to think he’d be interested in reading yet. But when Walt sneaked through the door, under his father’s arm, he let out a gasp of delight.

He had stepped into a kingdom: an oak labyrinth of bookshelves, corridors and canyons of literature beckoning him, whispering enchanting words Walt had never heard before. The air was smoky with the scent of leather, ink and paper, caramel-rich and citrus-sharp. Walt stuck out his small tongue to taste this new flavour and grinned, sticky with excitement. And he knew, all of a sudden and deep in his soul, that this was a place he belonged more than any other.

Hours later, staggering along the passage with armfuls of books, Walt had glanced up at another shop window to see two bright green eyes and a mop of blonde curls peeking out under a beaded hem. The eyes blinked as he stared and the sad little mouth opened slightly. Walt stopped.

‘Come on, Wally,’ his father had called, ‘we’re late for dinner.’

He’d said this as though there was someone at home cooking it for them, a wife and mother who anxiously expected them. He always spoke this way, as though denying his wife’s death could bring her back, if only momentarily.

‘But Daddy,’ Walt protested, ‘I want see the girl.’

His father had dropped the books then, pages fluttering to his feet. Tears filled his eyes and fell down his cheeks. Four years of silence, of doctors, specialists and speech therapy. Four years of nothing and now a whole sentence, in an instant. It was a miracle.

‘What girl, son?’ The question was a whisper on his lips. Walt turned back to the window, ready to point, but the girl had gone.

There are people who like to connect, to make eye contact and smile. Walt is not one of them. At school he learnt to make himself invisible, to watch people without being seen. And so he watched Cora growing up: staring out of the shop window while raindrops slid down the glass, wandering along counting paving stones, flower petals, leaves of ivy and anything else that inhabited All Saints’ Passage, sneaking into the bookshop to read biographies of Marie Curie and Caroline Herschel while entire afternoons slipped out of sight. He watched, biding his time before he finally found the courage to speak with her. And, even then, when they formed a tentative friendship in the years that followed, he was never able to look Cora in the eye and tell her how he felt.

When Walt turned sixteen, with enormous relief, he abandoned school to fulfil his second greatest wish (his first being the wish for Cora) and work in the bookshop full-time. When Walt turned twenty his father died, finally succumbing to the broken heart he’d been nursing for two decades. With the inheritance Walt bought his beloved bookshop along with the flat above it, and as soon as he moved in he stayed. He’s there for twelve hours a day, every day, even though the shop is only open for eight. But he loves the empty hours best of all, when he can walk along the aisles and bask in the warmth of the books, their glittering gold letters, their stories softly pulsing between pages just waiting to be opened and read and loved.

Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays are Walt’s favourite days, for these are the ones when Cora – at exactly 6:26 p.m. – opens the door and steps inside his kingdom. She stays for an hour while Walt gazes on, his eyes peeking out above Shakespeare or Milton or Garcia Marquez. He watches her weave along the aisles until she reaches the science section, slides a book off the shelf and sneaks into a hidden corner to read it. When Cora slips into the book she forgets herself entirely, allowing Walt to watch without worry, to gaze unabashedly at the wispy curls that fall over her face, delicate fingers cradling the book, lips absently mouthing the words, breath that occasionally quickens with excitement and shivers through her body in the most alluring way.

The very second the hour is up Cora, without looking at her watch, shuts the book then stands. On her way out she stops at the counter for a slice of cherry pie and a double espresso. She declines cream with the pie but takes four sugars with the coffee. Sometimes, if the book has been particularly brilliant and she’s forgotten to eat lunch again, she’ll have a second slice.

Sometimes Cora chats absently about scientific subjects Walt can’t understand, though he listens avidly anyway, nodding along and making agreeable sounds in what he hopes are the right places. Sometimes Cora only nods hello and says nothing, just eating, lost in thought. Since Walt rates the odds of his lips ever touching hers as less than his chances of winning the lottery, instead he bakes cherry pies so he can watch her eat. And, despite the sadness of knowing that this is the closest he’ll ever get to Cora, it’s still the most sensual moment of his day.

Apart from his love for Cora, Walt has another secret. A secret he’d love to share with her but knows he never will. He has always loved to read aloud, to hear words float about a room, to swim in stories and breathe in poetry. And he has a powerful voice, a beautiful voice, as deep, thick and rich as melted chocolate. Characters seem to come alive when he speaks, sliding off the page to stalk the bookshop aisles and relive their fictional lives in 3-D and Technicolor. At night, after Walt flips over the ‘closed’ sign on the front door, he sits back behind the counter and opens doors to other worlds: bookshelves transmute into swamp trees, floors into muddy marshes, the ceiling into a purple sky cracked with lightning as he floats down the Mississippi with Huck Finn. When he meets Robinson Crusoe, the trees become heavy with coconuts, the floorboards a barren desert of sand dunes whipped by screeching winds. When he fights pirates off the coasts of Treasure Island, the floors dip and heave, the salty splash of ocean waves stings his eyes and clouds of gunpowder stain the air. As a rule, Walt sticks with adventures and leaves romances untouched, preferring to escape his own aching heart rather than being reminded of it.

Occasionally, picking up a book during a quiet afternoon, Walt forgets himself and reads aloud to an unsuspecting and delighted customer. And, two years ago, on one fortuitous Friday, that particular customer happened to be the producer of BBC Radio Cambridgeshire. Walt didn’t need to be told that his was a face made for radio (not that the producer even thought this, let alone said so) but he needed some persuading that his voice was, too. He’d be perfect for the Book at Bedtime slot, the producer urged. Every night at ten o’clock he could pour words into perfect silence and assist drowsy listeners slip off to sleep. It was the thought of Cyrano de Bergerac that convinced him. Cyrano had been Walt’s personal hero for the last fifteen years, and he’d always wished that they’d shared an eloquent tongue as well as an enormous nose and an unfortunate penchant for unrequited love. But now, since he didn’t have any great words of his own, Walt was being offered those of great writers – now he could have a voice without a face. He said yes.

Tonight, Walt is sharing the wretched tale of Madame Bovary with his listeners. The story has sharpened its fingers on Walt’s fragile heart, snatching up little slices of flesh. This is exactly what he’s always striven to avoid, but for some reason his producer (a sorry sucker for romances) insisted on this particular book and now it’s wrapped the tragic twists of its plot around Walt’s chest, constricting his breath so the woeful words are barely audible any more:

‘Her real beauty was in her eyes. Although brown, they seemed black because of the lashes, and her look came at you frankly, with a candid boldness …’

The sentence scratches his throat. Walt thinks of Cora. He thinks of what Etta said: Some people don’t see the things under their noses. They mistake the everyday for what’s ordinary and unimportant. These people need shaking up. He isn’t a fool, he isn’t deluded by desire, he knows perfectly well what is possible and what is not. Cora is just a friend. She’s never shown the slightest physical interest in him so he knows absolutely that he’ll never experience anything with her, let alone passion and rapture. But he’s always accepted his hopeless situation fairly happily: the sight of her smile, the smell of her double espresso, the sound of her footsteps on the floorboards – this has been enough. Seeing Cora three times a week is enough. Almost.

It isn’t as though Walt has no other options, at least in theory. He has fans: women who phone the radio station asking for his address, phone number and marital status. They call him the Night Reader. They send him lustful letters and, occasionally, their underwear. They declare their undying desire, their dreams of making love to him while he sprinkles them with words and kisses until they explode. Of course, he never replies. And not because he believes they’ll change their minds as soon as they see him, but because he simply isn’t interested in anyone but Cora. And it’s been that way since the first time they spoke.

He was five and she was eight. He was sitting on the steps outside the bookshop, half-reading The Three Musketeers and half-watching her standing in front of a willow tree that grew over the alleyway wall, counting the leaves that dripped down to the pavement. Walt knew that was what she was doing, not only because he knew her quite well by now, but because she mouthed the numbers staring into the branches. Why he was suddenly seized by the courage to finally address her, he never knew. Perhaps the devious Milady de Winter, who’d just swept onto the pages of the tale, dared him to do it.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked.

She’d turned to him with a deep frown, instantly terrifying him. About to turn to escape back into the bookshop, Walt was stopped by her shrug.

‘Cora.’

‘That’s a funny name.’

‘It isn’t, actually.’ Cora’s frown deepened. She pulled herself up to her full height of four foot three inches. ‘Officially my name is Cori, but Grandma calls me Cora. I’m named in honour of Gerty Cori, the first woman winner of the Nobel Prize in medicine. I bet you didn’t know that.’

‘No,’ Walt admitted, embarrassed. ‘I didn’t.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘Walt,’ he offered quietly, expecting her to retort that his was an even sillier name, but she didn’t.

‘After the scientist?’

Walt frowned, thrown. ‘What scientist?’

Cora shrugged. ‘Maybe Luis Walter Alvarez or Walter Reed, but … actually Walter Sutton is the most famous. He invented a theory about chromosomes and the Mendelian laws of inheritance.’ Cora let slip a little smile of satisfaction at the blank look on the boy’s face. ‘Or maybe Walter Lewis—’

‘No,’ Walt interrupted, ‘I’ve never heard of any of them.’

‘Oh.’ Cora folded her arms and tilted her nose upward. ‘Then who are you named after?’ she asked, as if this was a given.

‘Walt Whitman,’ he retorted. ‘The poet.’

Cora considered this for a moment then shrugged again, a careful gesture this time, as if she were unburdening a heavy coat from her shoulders. ‘That’s okay, I guess. But poems, stories and that stuff are a waste of time anyway. They don’t answer any questions. They don’t help anyone.’

Walt swallowed the protest that rose up inside him and slid his book out of sight. ‘Don’t you like reading at all?’

‘What a silly question,’ she said, and then seemed to regret it and was kinder. ‘I have to read, to find things out. I’m studying to be a scientist,’ she added. ‘When I grow up I’m going to save the world.’

If he’d been curious, enchanted and infatuated with her before, that was the moment he actually fell in love.

‘How?’ Walt asked, though the answer didn’t even matter. Just the fact that she wanted to do such an incredible, enormous, ambitious thing was enough for him.

Cora shrugged for a third time. ‘Maybe I’ll discover a cure for cancer, or invent a special food that can grow anywhere and feed everyone, or a way to kill every mosquito or … something special like that, anyway.’

Walt just stared at her. Most of his time was spent lost in stories or play-acting out their plotlines – pretending he was twenty thousand leagues under the sea or journeying to the centre of the earth – and most of his thoughts were wasted on similarly pointless subjects. He’d never considered even attempting to do something so noble and amazing. That this girl had not only considered it but was, he was certain, actually going to do it, left him without words.

Cora narrowed her eyes at Walt, seeming to suspect him of mocking her with his stare, then her face relaxed. ‘What are you going to do when you grow up?’

‘Work here, in this bookshop.’

Walt replied without thinking, then instantly regretted it. Someone who was going to save the world would never be interested in someone who was going to work in a bookshop. But it was the truth, this was his one and only ambition in life, and Walt was quite incapable of lying.

‘Oh,’ Cora considered. ‘Why?’

‘I don’t know.’ Now it was Walt’s turn to shrug. The die was cast, there was no point in trying to snatch it back now. ‘Because … because I belong here.’

‘Oh,’ Cora said and Walt knew, with a sinking heart, that he’d given the wrong answer. ‘I’ve got to go home for tea,’ she said. ‘Bye.’ And with that she turned away, leaving him to gaze after her.

It’s a memory Walt has recalled so often that every second of it sparkles, like a ruby polished a hundred thousand times. It’s a great shock to Walt then, what happens next as he’s sitting in the studio, speaking softly into the microphone, following Emma’s tragic fate. The air in the studio booth is so still that the words bounce off the walls and echo through the room:

‘… her gown still hanging at the foot of the alcove; then, leaning against the writing table, he remained there until evening, wrapped in a sorrowful reverie. She had loved him, after all!’

It is this last sentence that does it. Those six little words tip the delicate balance of his fragile life, smashing it like crystal on to stone. And suddenly it’s clear to Walt what he must do. He has to act. He has to do something different. Something special. He has to shake Cora up.

Chapter Four

When his shift at the radio station is over, when he’s finally slammed Madame Bovary shut, Walt runs all the way back to the bookshop. Fumbling with the lock, he yanks at the door, scurries through the maze of bookshelves to the counter, then opens a drawer under the till and plucks out a book. He hurtles upstairs, through the hallway of his tiny flat, and falls onto the sofa in the living room. Sweating and panting, he sits up and waits to catch his breath. The book he holds is bound in rough red leather, worn at the edges and along the spine. Inside the words are handwritten, dotted with diagrams, faded with age and in a language Walt can’t understand. It had been his mother’s book, tucked, along with a pack of tarot cards, another book and a gold pen, into the side of his cot on the night she died.

Eva O’Connor had lived just long enough to see her son into the world and hold him once. Walt’s father hadn’t known about the rare condition that killed her and at first simply thought his wife was sleeping, a well-earned rest after twenty-six hours of labour. Walt was born at home and it wasn’t until nearly a week later that David O’Connor found his wife’s notebook alongside Leaves ofGrass, which was how Walt got his name. The bereaved husband and new father saved both books and gave them to his son on his tenth birthday. Walt has been trying to make sense of his mother’s legacy ever since.

Walt’s parents had met in an unorthodox way, a story that Walt had heard a thousand times and always cherished. Eva had been a fortune teller before she married; David, a slightly drunken visitor to the fair on Midsummer Common who went into her tent on a dare. In the ten minutes that followed she read his cards, then kissed him, and their lives changed forever. When the fair left Cambridge three days later, Eva didn’t go with it. Two years later Walt was born. As a boy he’d begged his father to tell him what his mother had read in the cards, but David had always claimed he couldn’t remember, saying that the delightful shock of the kiss had knocked the memory right out of him.

Walt must have gazed at the pages of his mother’s book a million times, desperately trying to make sense of the confusing and complex mess of curling letters, dots and lines. In an attempt to decode it he’s studied more than a thousand languages – past and present – but Eva’s words don’t match any of them. Sometimes he thinks it might be her own secret code indecipherable to anyone else but her. But why, then, would she have left it for him?

The year before David died, while they were carving out a pumpkin to celebrate Walt’s birthday on Halloween, he jokingly suggested it might be a spell book, which is why Walt consults it now. He’d laughed off the idea at the time but, since an air of mystery and magic always surrounded the memory of his mother, Walt secretly enjoyed entertaining the notion.

As he opens the book, tentatively holding the pages like the wings of live butterflies between his fingertips, Walt hopes that this time it will all suddenly make sense. He needs a spell or, failing that, a miracle to shake Cora up.

Walt closes his eyes and mumbles a prayer, a request for help. In the silence that follows he waits. Nothing happens. He opens his eyes. Still nothing. And then, just as he’s about to shut the book and stand, Walt hears the voice in his head. It isn’t his voice; it’s female for a start, and it doesn’t rise up from his consciousness. Instead each sentence seems to drop, fully formed, from the sky. Mum is the first thing Walt thinks, though of course he can’t remember the sound of her voice. Then he stops thinking and listens.

Seize your courage and show her your heart.

Walt sits up straight and still, holding his breath. The words fire through his blood, igniting every artery and vein in his body so his head pounds until he can’t think straight. But Walt doesn’t care about momentary intellectual impairment; he doesn’t care about thoughts, rationality and judgment. It’s all unimportant. His mind doesn’t matter because he has his heart. And something else of which Walt isn’t even aware: a little red star sewn secretly into the lining of his shirt.

Walt needs to act now. Right now. This second. Even if it is past midnight, it doesn’t matter. What he is actually going to do, along with the appropriateness of this undecided action, is irrelevant and immaterial. Walt has been waiting a lifetime for anything approaching a chance with Cora and he won’t wait another minute for his sudden courage to disappear.

Unsure of exactly what he’s going to do or say, Walt snatches up his mother’s notebook then dashes out of the flat and through the shop before he can change his mind or doubt himself. When he’s standing on the pavement he stops. Then takes a breath. What on earth is he doing? It doesn’t matter, it only matters that he’s doing it. He’s taking action. He’s doing something. He’s not a coward, he’s not scared any more.

Walt wonders if Cora will still be at her grandmother’s. He suspects so. Etta will probably have persuaded her granddaughter to stay and watch old films. He hopes so, since he doesn’t know where Cora lives, and is rather embarrassed to ask Etta but he will if it comes to that. For now though, he’ll try his luck. As he walks Walt wonders how Etta will take to a late-night visitor. Not too badly, he hopes, since it was Etta who put him up to it in the first place. Or at least put the idea of doing something crazy and courageous into his head.

When he reaches the front door of the shop he hesitates. Pulling himself up to his full height of six foot three inches, he knocks. He listens to the silence. All Saints’ Passage is dark, lit only by moonlight, without the assistance of street lamps. As the owners of the only two businesses on the street, Walt and Etta joined together to petition the city council for lighting but have so far been fobbed off with postponed promises. Walt taps his forefinger on the spine of his mother’s notebook and ponders his next move.

Cora is in the bathroom, splashing water on her face so she’ll stay awake until the four-hour film finally ends, when she hears tiny taps rattling the glass of her grandmother’s windowpane. She twists off the tap and walks into the next room. Another tap hits the glass. Cora hurries across the carpet, past the quilted bed. She fiddles with the catch and pulls the window open.

‘Walt?’

He smiles sheepishly. ‘Happy birthday, again.’

Cora frowns. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘I, um, I wanted to show you something.’

‘In the middle of the night?’

‘It’s pretty special,’ he says.

‘But it’s late,’ she says. ‘Why don’t you show me when I come to the bookshop tomorrow? That might be easier. Oh, and thanks for the pie. It was even more delicious than usual.’

Walt watches as she reaches up to pull the window closed again. The little red star stitched into his shirt tightens its threads.

‘No, wait!’

Cora frowns, her arms paused for a moment, her fingers tight on the wood of the window frame.

‘It’s a book,’ Walt blurts out, ‘my mother’s notebook. It’s in a special code and I thought … I thought you might help me decipher it.’

‘Oh?’ Cora releases her fingers. She still can’t understand why on earth Walt is coming to her with encoded diaries at – she glances at her watch – 12:06 a.m., but now her interest is piqued. She reaches out her hands above his head. ‘Why don’t you throw it up and I’ll take a look.’

‘No.’ Walt shakes his head, holding the book tight to his chest. This isn’t going at all the way he might have hoped. It’s no use. He’ll have to stop hiding behind other things and come right out and say it. And quickly, before she disappears again.