Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

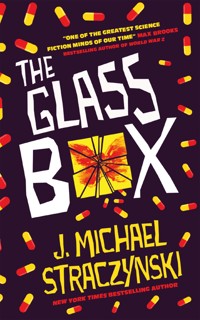

A tense, thought-provoking pressure cooker about a young woman imprisoned in a psychiatric facility for her political views, perfect for fans of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Girl, Interrupted. Riley Diaz is a troublemaker, born and raised. Half Irish, half Cuban, she's an orphan with the spirit and resilience of her ancestors and the protest protocols of her late parents. She's ready and able to resist the new tyrannies. After attending a protest, Riley is incarcerated in a shadowy American Renewal Center, detained under dangerous new legislation. This newly authoritarian government is trialling the mandatory re-education of dissidents, and Riley is receiving psychiatric treatment because of her politics. Riley is imprisoned in a nightmarish world of persecution and incursions on her freedom - forced therapy, involuntary medication, extended incarceration, solitary confinement, grotesquely restricted rations, false accusations and more. Trapped in an emerging dystopia, against people who would label her mad for speaking her mind, Riley can only do what she does best – rebel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by J. Michael Straczynski and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

The Rules of Engagement

Intermezzo

The Language of Doors

Algorithms of Advice

Seeking Shelter in Metaphors

Degrees of Fuckedupedness

Alibis in the Afternoon

Real Power

Ball Service

Starved for Attention

Consequences and Circumstances of Rage

Nothin’ Shakin’ But The Leaves on the Trees

Secondhand Crazy

Three Letters, One Word

Taking Control

Offended Gods and Answered Prayers

Shunk-Pop!

Boots on the Ground

About the Author

“[A] terrifically incisive tale … Readers should seek out this outstanding novel.”—Booklist

“Echoes of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest reverberate through this cinematic tale … readers looking for an adrenaline-inducing resistance plot will find this worth their time.”—PublishersWeekly

PRAISE FOR J. MICHAEL STRACZYNSKI

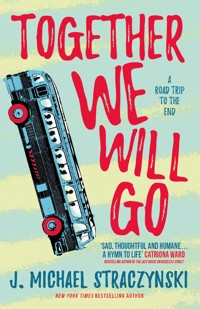

“Sad, thoughtful and humane, filled with vivid characters, Together we Will Go is a hymn to life and a mediation on suffering”—Catriona Ward, bestselling author of The Last House on Needless Street

“J. Michael Straczynski has written the Great American Roadtrip Novel to end all Great American Roadtrip Novels. Together We Will Go is tough, wild, brilliant, raucous, sad, an exaltation masquerading as an apocalypse and best thing Straczynski has written. If you’re going to take any literary road trips this year, take this one. Like all our best novels, Together We Will Go won’t bring you where you want to go; it will bring where you need to go”—Junot Díaz, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

“A conversation starter … compulsively readable, replete with compelling characters, surprising twists, and heady themes”—Starred Review, Booklist

“Acclaimed creator Straczynski manages to strike a note that’s lighthearted, peculiar, poignant and profound all at once”—Newsweek

“This novel challenges form and function and presents the meaning of life in a new, original way”—GoodMorning America Online

“Satisfying … a 21st-century epistolary novel … TogetherWe Will Go is, in the end, about friendship and learning to love”—Bookpage

“The cross-country road trip at the center of this novel is unlike any other … TogetherWe Will Go suggests that the decisions we make are based on the choices we have”—AltaJournal

Also by J. Michael Straczynski and available from Titan Books

Together We Will Go

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Glass Box

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364223

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803367309

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© J. Michael Straczynski 2024.

J. Michael Straczynski asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Dedicated to—the troublemakers

The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies. They are the standing army, and the militia, jailers, constables, posse comitatus, etc. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgement or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw or a lump of dirt . . . Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others—as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and office-holders—serve the state chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the devil, without intending it, as God.

Henry David Thoreau,Civil Disobedience

Never run when you’re right.

Frank Serpico

THE RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

Riley Diaz strapped kneepads over her jeans in preparation for the day’s march, pulled on a heavy leather jacket, and checked her reflection: barely five feet six, slender but wiry. High-topped boots to keep her ankles from turning while running. Check! Fabric gloves, less likely to hold fingerprints. Check! Neck mask gaiter and scarf. Check-check! Backpack contents: first aid gear, loose cash, protein bars, nail clippers and file, cheap burner cell phone, air horn, visor, sunglasses, spare clothes, plastic raincoat, folding umbrella to defeat cameras, extra keys, tampons, water and baking soda to neutralize tear gas. Checkety-check-check!

Satisfied that she hadn’t forgotten anything, Riley picked up the motorcycle helmet she’d adorned over the years with art and some magnificently rude comments, slid it down over her short black hair—her Cuban father’s legacy—until it fit snug, then pulled up the gaiter and slapped down the faceplate. All that could be seen of her face were two blue eyes—her mother’s legacy, first generation Irish American by way of Staten Island—bright enough that even the faceplate couldn’t hide them. Then she grabbed the keys to the motorcycle and headed out.

Riley knew they would come for her sooner or later.

She knew it when everyone got used to seeing people penned in chain-link cages for the crime of walking from somewhere over there to somewhere over here. Then they started caging the same kind of people even though they were actual citizens of over here, which everyone said couldn’t possibly happen because there were laws and guardrails against that sort of thing, except the laws got rewritten to make what was illegal yesterday legal today, and what was legal yesterday illegal today, and nobody—absolutelynobody—with the power to Do Something About It even blinked, and people got used to the idea and started calling it the New Normal, and once that train starts it doesn’t stop until it comes right through the front door and oh look, a pony!

Ten thousand protesters packed downtown Seattle, a sea of voices, drumlines, banners, and rave-wear worn mostly by newbies who would zoom at the first notes of the rubber bullet symphony without understanding that their colorful clothes would just make it easier for the police to find them later. Even though the protest had been determinedly peaceful, cordons of tactical teams in helmets and Kevlar stood ready behind plexiglass shields at the other end of the street. Some held batons, while others cradled snub-nosed tear gas cannons that would be used to contain the crowd, a tactical strategy that could be augmented by automatic weapons if things went slantwise, which didn’t usually happen, but that was a long goddamned way from saying it never happened or that it wouldn’t happen today.

Yeah, Riley thought, they’ve got weapons and tanks and shields, but we’ve got volume and enthusiasm on our side!

Also, for some reason, an unusually high number of bunny ears.

Riley knew that sooner or later they would come for her when the new president rode into office on a wave of resentment after several city blocks went up in flames during the latest round of protests against urban squalor. The candidate, his spokespeople, and the TV Talking Heads Who Liked Him a Lot blamed the protesters, who had been marching in peaceful, orderly rows when the batons started falling, even though the actual footage showed Molotov cocktails thrown through windows by groups carrying the candidate’s banner while yelling, “Burn it all down.” But for some strange reason, the TV Talking Heads failed to mention that part of it, or the fact that all the places that would have been prime targets for the protesters—corporate headquarters, banks, and police stations—came through unscathed, while the low-rent housing projects that burned down were the very same buildings the protesters were trying to save, because that’s where they lived—a remarkable irony that cleared the way for friends of the candidate to scoop up those lots cheap for redevelopment as shopping malls and hotels in the ultimate fire sale.

“This kind of criminal violence cannot be tolerated and will not be allowed to happen again,” the new president said. His first official act was to revive an antiprotest program created back in 2020 that stitched together agents from the Justice Department, Homeland Security, the Bureau of Prisons, and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement into a tactical strike force answerable only to the president. A single executive order, barely noticed by the press, reassembled that coalition and created a new national police force that, after weeks of research and testing by focus groups to find the right name, was cunningly designated the National Police Force (NPF), which operated under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice.

“This new policing system will coordinate national peacekeeping efforts, and supervise investigations across local and state jurisdictions in our ongoing effort to keep the country safe,” the attorney general said, reassuring only the people who didn’t fully understand what he’d just said.

In 2020, a twelve-year-old Riley had decided that she was old enough to ask her parents to bring her along to a protest. Her mother hesitated, then said, “Okay, we can start taking you along if we think it’s safe, but only after we’re sure you understand the Rules of Engagement.”

Rule One: Never do anything illegal, remain peaceful, and never go looking for a fight. They want you to break the law so they have a reason to come in swinging; gives ’em something to point to later as proof that we weren’t peaceful protesters, we were lawbreakers and they had to step in to restore order.

The NPF, on the other hand, was always eager to jump in, all rage and batons, dragging people into waiting vans even when nobody had broken the law. When videos surfaced later proving that the protests had been peaceful before the jump, reluctant apologies (totally insincere, but everything starts somewhere) were followed by settlements and a few badges, but that’s where it ended because it’s easier to boot out the people than change the policies.

Protesting isn’t just about being mad at something, her mother had said, it’s about being right and true and honorable, and proving it.

When people start getting picked up off the street for no reason, when they get disappeared or beaten, when the government falls into unethical hands and there’s tyrannyafoot—Riley loved that her mother used words like tyranny and afoot spoken in a voice that was 50 percent Irish lilt, 50 percent New York badass, and 100 percent do-not-fuck-with-me—youhave to do everything you can to gum up the works. You put sand in the engine to buy time for the people with law degrees and important positions to stop what’s going on, hobble it, or if all else fails, show the world the truth of their intentions.

That’s why we protest. We put our boots on the ground and our bodies in the way of the Machine; we make noise, draw attention to what’s happening, and force the bully boys and the tyrants to answer questions like, If what you’re trying to do is so important, so right, then why are so many people upset about it, why did you hide it, and why are you lying about it now that you’ve been exposed, laddie boy?

Riley knew they would come for her sooner or later once the NPF started arresting protesters not because of anything they’d actually done but because somebody decided that they might do something someday or had the wrong attitude or deliberately chose to go outside while black or Hispanic. To look like trouble and talk like trouble was to be trouble, which was all the evidence the government needed anymore, and you got what was coming to you, but this just put more people in the street, because if they were going to arrest you for doing nothing, then you might as well do something. The protests grew in size and frequency—at first yearly, then seasonally, monthly, and weekly—until there were protests nearly every day over the latest government outrage.

Riley’s mother had always taken great pride in the knowledge that her family had fought against the English occupation of Ireland for five generations, and that line still ran true in her. She believed in the value of protest. She believed in the Rules.

But the rules changed when the laws changed.

Masks fucked with facial recognition systems the police used to track protesters, so wearing masks at protests became illegal.

The police used rebreathers and face shields to protect themselves from tear gas, but they didn’t want protesters to have the same advantage, so they made those illegal too.

Looking for a water kiosk where you can get a drink on a hot day or wash CS gas out of your eyes? Nope. Rebranded as operating an unlicensed food store, which was illegal, and Bam! Take ’em away, bailiff! Standby medics for when somebody gets a rubber bullet in the eye? Redefined as operating an unlicensed drug-supply store providing unauthorized medical services. Illegal. Bam-bam!

Meanwhile, the NPF were equipped with Armored Police Vehicles, tanks, and military-grade weapons (but strangely lacked nameplates or other identifiers on their uniforms) that let them do whatever they wanted to you, while making sure that there was nothing you could do to defend yourself, and if you tried, ba-BAM!

Just by showing up today, Riley had already broken at least six laws.

She glanced up as the NPF squads straightened at the same time, which only happened when orders came in through their headsets. Usually that meant somebody had just said, “Go get ’em!” but for the moment they remained in place. Sometimes they’d play it easy if there were too many cameras around or in hopes that the crowd would burn itself out as fatigue set in. But this time everyone knew that the situation had gone too far for fake-outs and compromise.

What did they just hear? she wondered. What was the order?

How long do we have?

She didn’t want to be here, would’ve given a kidney to be anywhere else. But the Ten-Plus ruling was too awful to ignore, even for those trying to lean into the middle, and lines were being drawn in simultaneous showdowns in dozens of cities across the country.

The Founding Fathers, being reasonably smart guys, had written that the right of the people to peaceably assemble will not be abridged. But even the brightest among them could never have anticipated the day a United States senator would stand up before his ninety-nine best pals ever and say, “It occurred to me the other day that the Bill of Rights doesn’t actually mention how many people that right applies to in the same place at the same time.”

When the NPF used this rationale to ban gatherings of any size, the case quickly landed in front of the Supreme Court—recently reconstituted to make it more politically malleable—where an attorney for the Justice Department laid out his argument.

QUESTION: Would the Court concede that an unregulated assembly of a million people in the middle of New York City would constitute an unacceptable risk to life and property?

ANSWER: Yes.

QUESTION: Does the Court also concede that the Amendment does not provide any guidance as to how many people should be allowed to assemble at the same time?

ANSWER: Yes.

QUESTION: Does the Court also acknowledge that at the time this document was written, travel was extremely difficult, making it hard for large groups of civilians to congregate in one place, further suggesting that the authors were likely thinking in terms of much smaller gatherings?

ANSWER: Yes.

QUESTION: And does the Court still agree with prior decisions made by this body concerning the Second Amendment, which stipulate that since it was written at a time when weapons were limited to muskets, it thus does not apply to some forms of heavy-duty armaments that only came along later?

ANSWER: I believe the majority still concur with those decisions and the proposition that the Founding Fathers could not have anticipated the social and technological changes that have arisen since the Bill of Rights was drafted. It has also been established, during the Coronavirus pandemic, that State and Federal Governments have the authority to limit the size and location of gatherings in the public interest, necessity, and convenience. That being the case, viewed from an originalist standpoint, what size of gathering does the Government feel was the intent of the First Amendment?

QUESTION: We’re talking specifically about being outside, in open public spaces, yes?

ANSWER: Yes.

REPLY: Ten people.

Everybody assumed they’d get laughed out of court.

It passed 5 to 4.

The attorney had gone out of his way to stipulate that the new Ten-Plus restrictions only applied to outdoor settings to ensure that indoor gatherings at bars, restaurants, and country clubs were still considered legal. Baseball and football stadiums and outdoor concerts were also permitted, because money.

Within hours of the ruling, thousands of boots around the country hit the ground in opposition.

Riley was among them.

Because she knew.

They would come.

For her.

Sooner or later.

They would come.

To go outside was to risk everything.

But staying home was increasingly no safer.

Because sooner or later.

Fine. Bring it.

Today’s protest marked week three, day four of the Ten-Plus Uprising.

Nine years, five months since her mother taught her the Rules of Engagement.

And four years, two months, and seven days since an eighteen-wheeler blew through a stoplight, T-boned their car, and tumble-dragged-pushed her parents down the street for a hundred yards before shuddering to a stop. The officer who gave Riley the news had always considered them “troublemakers” and took great pleasure in noting that there was barely enough of them left to put in a shoebox, which didn’t go over well, and somehow a broom appeared in her hands and—

Riley glanced up as the police suddenly began checking their weapons and shields, and she knew that the order to advance had been given.

Rule Two, her mother had told her, Never make the first move. Don’t push them into a corner or force them to do something that there might still be a chance to avoid.

“Here they come!” someone yelled from the front of the line.

Rule Three: Always make the second move. That means you don’t run away. Look after your people. Protect them where you can. Stand firm.

Riley threw a fist in the air. “Boots on the ground! Bodies in the way!”

The crowd echoed the words, fists raised, closing ranks. “Boots on the ground! Bodies in the way!”

The moment when the police started to advance never failed to send a chill down her spine. Which was, of course, the intent. Uniforms, armor, horses, shields, and APVs all moving forward at the same time, perfectly synced, creating the overwhelming sense of a machine made of wheels and gears and teeth and blades that didn’t give a shit what was in front of it.

Then the machine hit the front lines, and the crowd splashed and surged and pushed back, the police broke ranks and suddenly it was everyone for themselves, a roar of sirens and thousands of voices shouting at the same time, falling back or giving instructions, yelling and cursing as batons fell and flash-bang grenades flash-banged and there was blood everywhere as clouds of tear gas swirled through the crowd and the newbies ran or fell to their knees vomiting.

Somebody yelled, “Fall back!” and as the crowd pulsed south, Riley saw an old man facedown in the street, beaten and barely conscious, reaching for help, but no one was there—

Rule Four: Leave no one behind.

—and as more flash-bangs exploded, she ran to him, slung one arm over her shoulder, and began pulling him away, moving south, where there would be medics and water and they could regroup and—

Then something hit her from behind, the world kicked sideways, and she fell into the soft black.

INTERMEZZO

WASHINGTON (AP) —Dean Jurgens, the acting director of Homeland Security, announced the opening of 16 counseling centers in New York; San Francisco; Seattle; Miami; Portland, Oregon; and 10 other cities as part of the Safe Streets initiative.

“These clinics, designated American Renewal Centers (ARCs), are equipped with counselors, doctors and teaching staff dedicated to the cause of peace in our country,” Jurgens said. “Many of those who take part in the mass disruptions we’ve seen recently are well intentioned but have allowed themselves to be used by anarchists, terrorists and agents working for foreign powers determined to tear down this country and everything it represents. These people have fallen victim to the virus of extremist propaganda designed to whip them into a frenzy of instability and convince them to walk away from family and friends, with only their paid handlers to tell them right from wrong. This programming makes them a danger to themselves and others.

“The intent of the ARC program is not to punish these people, but to free them from the influence of violent extremist propaganda so they can return to the world as functioning members of society. To that end, the DHS will assist families and local community leaders requesting preemptive interventions and give those who have been found guilty of protest-related offenses the option to avoid jail by attending these centers for six months of counseling under the guidance and supervision of dedicated, trained and caring professionals.”

THE LANGUAGE OF DOORS

Handcuffed and hard-strapped into the rear seat of an NPF police van, Riley craned her neck to peer out the window at the passing streets. The court paperwork said she was being sent to a facility in Ballard, in northwest Seattle. She’d never been to Ballard before, but so far it seemed to consist mainly of quiet, tree-lined streets dotted with restaurants and cute shops. She thought it’d be fun to stop for coffee but suspected the armed and armored cops sitting up front might have something to say about the idea.

West on Sixty-Fifth, then north on Twenty-Fourth, she mouthed silently, memorizing the streets with each new turn, less interested in knowing where they were going than being sure she could reverse the sequence to get back out again.

Because she had zero intention of staying put.

It’s a hospital; assuming I can’t just talk my way out, how hard could it be to slip away and get back into the fray? The first obligation of a prisoner is to escape!

Agreeing to spend six months in a mental health facility instead of the Mission Creek Corrections Center was a calculated risk. Jails were good at hurting you on the outside, but psychiatrists knew all the ways to hurt you on the inside. Some of her friends who had gone into mental hospitals for treatment came out stronger, but as for the rest, it seemed like every time they went in, a little less of them came back out again. She wanted no part of whatever they had in mind for her mind. She wanted only a wall low enough for her to climb over and get to the other side.

Four more turns brought them to a long, gated driveway beneath a sign depicting a bright ocean sunrise beside the words Westside Behavioral and Psychiatric Residences. A second sign just above it, newer and more hastily erected, read American Renewal Center #14.

They parked in front of a whitewashed three-story building labeled Inpatient Treatment. The upper-floor windows were covered in ornate wrought-iron designs: cats and dogs and giraffes and parrots woven into elaborate backgrounds of vines and branches. Bars designed not to look like bars to the people inside, even though that’s exactly what they were. Happy barred windows.

They unstrapped her from the rear seat and led her through two sets of reinforced glass doors to the check-in station, where a receptionist in a bright green floral-print dress folded her hands and smiled in a calculated-to-the-kilowatt welcome.

As one of the officers handed over the paperwork, the other unlocked the handcuffs but kept a firm grip on Riley’s arm in case she tried to run. The receptionist flipped through the pages and signed where required without making direct eye contact with her.

Screw that, Riley decided. Doctors, police, and serial killers had one thing in common: your odds of survival absolutely depended on making them see you as a human being.

“Hi!” she said, smiling broadly.

The receptionist glanced up, startled. “Hi,” she said before she realized she’d done it, then quickly turned her attention back to the forms.

“Nice place.”

The receptionist nodded but didn’t reply, trained to avoid contact with new arrivals by remaining bureaucratically anonymous.

Okay, Riley thought. Initiating the How Far Can I Push This Before You Realize I’m Fucking With You? program in five, four, three,two—

“I don’t want a room with a giraffe.”

The receptionist paused, pen poised over the last line of the form. “Sorry?”

“The windows have animals on them, and giraffes freak me out. Something about the necks, you know? I get really nervous and scared and out of control, and I don’t want to be any trouble. Can you check?”

Uncertain eyes flicked from Riley to the cops and back again. “I suppose . . . just a second.”

A monitor flared to life, and with a few clicks she summoned up the details of Riley’s assigned room. “It doesn’t say. There’s not a field for the window design.”

“Can you find out?” Riley asked, still smiling.

The receptionist toggled a microphone on her desk. “This is Maria at the front desk. Could an orderly let me know what the window design is in room twenty-one forty-one?”

“Thanks, Maria,” Riley said, enjoying the look on the receptionist’s face when she realized that she’d not only acknowledged Riley’s existence but had inadvertently provided her name.

The speaker buzzed back at her. “Parrot,” a man’s voice said.

“Parrot,” the receptionist parroted.

“Perfect,” Riley said, feigning relief.

The cop holding her arm shifted impatiently. “Can we get this over with?”

“Of course,” the receptionist said, “sorry.” She signed on the last dotted line, tore off the receipt at the bottom of the page, and handed it back. “All set.”

She buzzed the intercom again, and a tall African American orderly came through a security door behind them.

“We’re good to go,” Maria said.

The orderly took Riley by the arm with 50 percent less pounds-per-square-inch of pressure, just enough to say I’ve got you without the subtext of Does this hurt? Want to make something of it?

As they passed into a long, puke-green hallway, Riley glanced at the nameplate pinned to his crisp white shirt: Henry.

“You know it’s safe to let go of me, right, Henry?”

“Probably, yeah, but the rules say we have to maintain contact and control of all patients until they’ve been processed.” His voice was firm but surprisingly gentle. “Just a little longer.”

He led her through another set of doors—the door manufacturing business was apparently the place to be these days—to an administrative area, nodding and smiling at the support staff working in cubicles and small offices, the buzz of their voices low and efficient. At the end of the hall was an office with a brass nameplate that read Dr. Lee Kim, Chief Administrator.

Henry knocked on the open door. “The new patient’s here, Dr. Kim.”

“Bring her in.”

Dr. Kim stood as she entered: late fifties, slender, Korean. The diplomas on the wall showed accomplishments and the photos on his desk showed a family man. “Please sit.”

She sat in one of two straight-backed chairs as he settled behind his desk and checked her file on his desktop monitor. “You’re here for observation under the ARC program,” he said, trying to sound chipper about it. “Six months.”

“Unless you want to leave the back door open and look away for a second.”

He smiled thinly and glanced away. He doesn’t like this arrangement any more than I do, she thought with a measure of hope.

“Since you’re going to be with us for a while, would you like me to tell you a little about Westside?”

“Sure,” she said. Yes, let’s change the subject to something more comfortable for one of us.

“For twenty years, this was an assisted-living facility, then twelve years ago it was acquired by our parent company, upgraded, and turned into an inpatient mental health hospital offering round-the-clock treatment for acute psychiatric problems, drug addiction, anxiety, alcoholism, bipolar disorders, and depression. Our programs include individual counseling and group therapy sessions, therapeutic medications, and medical evaluation and management.”

He continued to work through the list of protocols, as if stressing what the hospital used to do would let him avoid addressing what it was doing now.

“And now it’s a prison,” Riley said.

His face tightened. “We don’t have prisoners here. We have patients.”

“Well, both begin with the letter P, so there’s that, I guess.”

“Many of our patients check themselves in for treatment, but we’ve had a good history of working with the courts in situations where individuals are brought here because they represent a danger to themselves or others.”

“So why am I here?”

“You came in through the courts, the usual channel.”

“For the usual reasons?”

He shifted uncomfortably in his chair. “That decision is outside our jurisdiction. And technically, since you signed the transfer forms, this constitutes self-commitment.”

“Then I’d like to self-uncommit.”

“We can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“It’s not my place to discuss hospital policy—”

“But you’re the administrator.”

“Yes, but our license to operate requires cooperation with the state and federal agencies that regulate our industry, as well as law enforcement. The state board of health selected us to participate in the ARC program, and that’s what we’re doing.”

“So you’re as much a prisoner as I am.”

He turned back to her file to avoid addressing the point. “Your records indicate that you have a bit of a temper.”

“Cuban and Irish. Work it out.”

“Also artistic, extremely bright, and can be very well spoken when necessary.”

“Cuban. Irish.”

He switched off the monitor and leaned back in his chair. “I’m going to be straight with you, Riley, because I think you’re smart enough to know what’s in your best interests. Under the new rules, I don’t have direct authority over your treatment or the term of your stay here. All of that falls under the jurisdiction of Homeland Security and the ARC program, which, at this center, is run by Mr. Thomas McGann.”

“Mister? So he’s not a doctor?”

“No,” Kim said, and he was grinding his teeth as he said it.

“Are all the patients here part of the ARC program?”

“No, most were here before the new mandate. So far, we have less than a dozen admissions like yourself, but I’m told that more are on the way. The original patients will eventually be moved to another hospital, but it’s taking a while to find beds given how tight things were in the first place. For now, everyone shares the same facilities and common rooms. McGann has his own staff and his own priorities, which operate outside my authority. What I’m trying to say is that under the circumstances, the best thing you can do during your stay is to try to fit in.”

“And if I don’t?”

“I’ll leave that to Mr. McGann to explain.

“One last thing,” he said, lowering his voice as he buzzed for the orderly. “Our hospital is one of several that have filed a lawsuit protesting this arrangement with Homeland Security. The case will take time to make its way through the courts, possibly a long time, and there’s no telling where things will end up when we finally do get in front of a judge. So my advice would be to avoid compromising your position while this case makes its way through the system. Don’t give them anything they can use against you.”

“For the next six months.”

Kim raised his hands in a way that said not my fault. “That’s the deal you signed,” he said.

Then the door opened and Henry entered. “Ready when you are, Riley,” he said, then smiled. “Ready Riley. From now on, that’s your nickname.”

Henry led her into an office new enough that it didn’t have a nameplate. The man she assumed was McGann stood inside with his back to her, looking out the window. Once Henry had stepped out and shut the door, McGann turned to her, revealing a thin, severe face that was younger than Kim, probably late forties, but felt older, with hay colored hair and dark, unforgiving eyes. “Sit,” he said, as though giving instructions to a dog.

She remained standing.

“I’ll be brief,” he said. “The waiver you signed that authorized psychiatric treatment in lieu of incarceration acknowledges that the violent tendencies you exhibited that led to you being arrested were the result of extremist influences and mental instability. The waiver stipulated your desire for corrective therapy, and ceded to us the legal authority to take whatever steps we deem necessary for your treatment, so there will be no debate on any of those subjects. During your stay, you will be evaluated on a points system. Constructive, cooperative behavior earns points. Uncooperative behavior subtracts them.”

“If I get enough points, do I win a stuffed panda?”

“At the end of the six-month observation period, your accumulated points will be factored into our decision as to whether or not you have made sufficient progress to be released. If not, we have the option of extending your period of treatment for another six months. We cannot turn you loose on society if your violent tendencies remain unaltered. Should your condition remain unsatisfactory, we have the authority to prolong your stay for as long as is required to give you the help you need.”

A hard knot formed in Riley’s stomach as the implications sank in. Nobody had explained this part when she signed the paperwork. If she’d remained in jail, at least there would have been a clear release date. But if McGann was telling the truth, and the pleasure she saw behind his eyes left little doubt of that, there was no such thing as a statutory limit when it came to psychological disorders. Her release would be subject to their opinion about her mental health, which was completely subjective.

McGann picked up a pen and notepad from his desk. “When you were arrested, several incriminating items were found in your possession, ranging from weapons—”

“It was a nail file.”

“Which could have been used to gouge out an officer’s eye or damage zip ties for the purpose of escape. There was also a burner phone which they managed to unlock—”

“By shoving it into my face.”

“—but which did not contain contact information for the other protesters. I doubt you memorized all their phone numbers and email addresses, which means you’re probably using a cloud-based text and voice-mail system. So, as a show of good faith, I want you to write down the URL for the system, your username, and password.”

He held out the notepad. “And I want you to do it right now.”

She took the notepad and began writing, then held up the page for him to see.

Cloud server: FUCKYOU.COM

Username: FUCKYOUTWICE

Password: ANDFURTHERMOREFUCKYOU

He tore off the page and slid it into a folder. “You’ve been here for less than an hour, and you’re already down ten points.”

“I’ve always been an overachiever.”

He looked past her as though she no longer existed and pushed the intercom.

“So, how many points do I start with, and how many do I need to get out of here?”

“I’m afraid that’s proprietary information.”

How convenient, she thought, but for the moment, did not say.

The door opened and Henry reappeared. “All done?”

McGann nodded, then as Riley was led out, added, “We’re here to help you. You may not understand that now, but you will in time. I believe that when this is over, you will thank us for intervening while there was still the opportunity to put you back on the straight and narrow.”

“So, how’re you holding up?” Henry asked once they were on the other side of the door.

“Swell,” she said flatly.

He laughed at her tone. “Yeah, I hear you. Okay, just one more stop, then we’ll get you to your room and you can catch your breath.”

“So have you been here for a while, Henry, or are you part of the new crew?”

“Started here three years ago. It was a great place to work, lots of good people.”

“And now?”

He shrugged. “Not my place to say.”

He opened a door to an examining room. “Dr. Nakamura will be right in to do the admission examination. Medical gowns are on the shelf over there.”

“Is this really necessary?”

“Afraid so. See you in a bit,” he said, and shut the door.

As Riley shivered in the cold room, she thought about refusing to change into the thin gown but decided it wasn’t worth the fight. There would almost certainly be bigger and better hills to die on later.

Once she finished changing, she sat on the examination table and waited for the doctor, growing sleepy with the silent, passing minutes. Stress reaction. Haven’t had much time by myself to process everything. She pushed through the fatigue. Don’t give them an advantage.

It was almost half an hour before Riley heard the rattle of paperwork in the wall folder outside the door. A moment later, the doctor—slender and dark-haired with a white coat over a deep-blue dress—stepped inside.

“Riley Diaz?” she asked with a slight British accent.

Riley nodded.

“Eleanor Nakamura.” She settled onto a rolling chair near the table. “Sorry for the long wait, we were having an issue with one of the other patients. He’s taking a bit of a nap now.”

“So are you in charge of the ARC patients?”

“That would be Dr. Edward Kaminski. You’ll meet him tomorrow, after you’re settled in. I spend most of my time running individual counseling sessions in cognitive therapy, but pitch in to handle new patient admissions when the staff is busy with other things.”

“Like whoever’s taking a nap?”

“Exactly. So, how are you feeling?”

“I’m good.”

“Excellent,” she said, switching on a tablet. “I have a few questions so we can finish processing your admission for treatment, then a quick physical, and you’ll be on your way. Are you having any issues with depression? Anxiety? Any suicidal thoughts?”

“Not until I got here.”

The room abruptly dropped several degrees as Nakamura’s gaze turned clinical, flicking from the screen to Riley.

Oh, hello, Skynet! Wondered when you were going to show up.

“We can do this quickly, or we can make a game of it,” Nakamura said. “Your choice. I’m paid by the week.”

“No, ma’am, no depression or any of the other stuff.”

“Have you been treated previously for behavioral issues?”

“Nope.”

“Any mental health issues in your family?”

“None.”

Her eyes flicked up again. “You say that with a great deal of certainty.”

“Never came up.”

“People often avoid talking about any mental health problems they may be experiencing, but that doesn’t mean those issues are invisible to family and friends. In response, we can become co-enablers, teaching ourselves not to see what we’re seeing, in order to avoid confronting them with truths they don’t want to hear about. So, regardless of what anyone did or didn’t say, did you ever see anything in your family that might suggest psychological distress or instability?”

“My folks weren’t crazy.”

“Not what I asked you.”

“Then no, I didn’t see anything.”

Nakamura swiped up to another screen. “Are you married or single?”

“Single.”

“Boyfriend or girlfriend?”

“Not at the moment.”

“What sort of work do you do?”

“Temp agency.”

“Doing what?”

“Whatever they need me to do. Babysitter, assistant, cook, clearing out garages—”

“Would you say you’re financially unstable?”

“These days, who isn’t?”

“Do you find that stressful?”

“I get by.”

“Yes or no, please.”

“No.”

Another screen.

“Any visible cold sores?”

“Can I borrow a mirror?”

Click! The look. I’m a cybernetic organism, living tissue over a metal endoskeleton. Have you seen Sarah Connor?

“No, ma’am.”

“Any major traumas in your life?”

“Yes, and I don’t want to talk about them right now.”

“Later, then?”

“Probably not. Is there more, or can I go?”

Nakamura’s fingers slid along the screen as she made a quick entry. “Do you use any recreational drugs?”

“Patient declines to answer.”

Nakamura switched off the tablet. “That leaves just the physical exam, and we’re done,” she said, snapping on a pair of nitrile gloves. “Please lay back on the table, this will only take a moment.”

* * *

“All set?” Henry asked.

Riley shrugged. Being poked and prodded by Nakamura made her feel like a piece of meat. Dismissive and as cold as the room itself. At least the hard part’s over, she decided.

Wanna bet? another part of her fired back.

Three more puke-green hallways, four doors, and a passkey-activated elevator brought them to the second floor. Room 2141 contained a narrow bed, an empty bookshelf, one plastic chair beside a small table bolted to the floor, and a bathroom with a metal toilet and a metal mirror screwed into the wall above a sink. The few extra clothes she’d brought to the protest were spread out on the bed. Everything else had been confiscated.

“I thought we’d all be wearing hospital gowns or uniforms,” she said as she picked through the clothes.

“Everyone assumes that, but no. Some patients spend years here, so the doctors want the hospital to feel as much like the outside world as possible. That way it’s not too much of a shock when they leave. For the same reason, male and female patients are allowed to congregate in the common rooms under staff supervision, though for safety reasons you’re not allowed to take other patients into your room unsupervised.”

He began going down a series of bullet points on his clipboard. “The entire first floor is restricted to staff only. You can move around the common areas on the second and third floors as long as you don’t interfere with the staff or upset the other patients. This floor has private rooms for examinations, medical treatment, individual therapy sessions, and a cafeteria. The women’s shower is at the north end of the building, men’s on the south. Third floor has larger rooms for group therapy sessions, an exercise room, and an arts and crafts room with music players and headphones along with some magazines, though somebody keeps tearing pages out of the damned things, so if you see who’s doing it, let me know. There’s a separate area on the third floor for staff members on shift that’s also off-limits to patients.

“You’re expected to be back in your room by ten p.m., with lights-out and lockdown at ten thirty. Rooms are unlocked at seven a.m., breakfast at eight, lunch at one, dinner at seven. Should you experience a medical emergency during the night or at any other time, there’s a panic button by the bed that rings the on-duty nurse’s station. If you’re thinking about using it for laughs, don’t—the ODNs have no sense of humor, and you’ll lose a lot of points because it could take them away from someone in actual need.

“You’ll get your therapy schedule tomorrow morning. If you have any nonmedical questions, you can ask me or any of the other orderlies. I know this is a lot to process on day one, but you’ll be okay. I got a good feeling about you, Ready Riley. One day at a time, right?”

And then he was gone.

Riley sat on the bed, closed her eyes, and let out a long, slow breath, forcing calm. You’ll be okay. Like he said, one day at a time, right?

When she opened her eyes again, the elongated shadow of the metal parrot in the window was stretched out on the bed beside her, cast by the fading afternoon light.

“Don’t get too comfortable,” she said to the shadow. “We’re not staying. One way or another, we’re getting out of here.”

The parrot declined to comment.

ALGORITHMS OF ADVICE

Having arrived too late for dinner, Riley decided to take a quick shower to wash off the jail and the road, then scope out the second floor in search of vulnerabilities and snacks.

She found neither. But she did run across a vending machine marked with a sign that read Staff and Authorized Patients Only. She peered through the plexiglass window at the rows of chips, pretzels, candy bars, and Life Savers. Hello, little buddies, I missed you. Maybe I can come visit sometime.

“Do you have change?”

She turned to see a man standing behind her, a few inches taller and a few years older than she was, with soft green eyes beneath a tangle of blond hair. “The machine only takes exact change.”

“Fresh out,” she said.

“You got anybody on the outside who can send you money?”

She hesitated.

Rule Five: If you get arrested, assume that anyone who approaches you on the inside is a plant gathering information to be used against you. Trust no one.

“No, nobody.”

“Probably doesn’t matter since you’re not authorized.” He dug into his pocket and pulled out a fistful of quarters. “What do you want?”

“Snickers.”

As he carefully counted out eight quarters, Riley saw deep worry lines around his eyes. This was someone who felt he had to get everything right all the time.

He checked the amount again, then slid four quarters into the machine, pushed G7, and a Snickers bar tumbled into the pickup tray. More coins followed, and a bright-red Kit Kat was released from its spiral cage.

“Thanks,” she said, unwrapping the Snickers. “So are you staff or an authorized patient?”

“Patient,” he said.

“And how does a patient get authorized?”

“Well, you can either become the pet project for one of the doctors, or come from a family with a lot of money, and my family is made of money, going back six generations.”

“And what are you made of?”

He pulled back a sleeve to reveal scars from deep cuts stretching up from his wrist. “Depression, apparently.”

“Sorry. Didn’t mean to pry.”

“It’s okay.” He slid his sleeve back into place and began walking her down the hall. “There aren’t a lot of secrets in this place when it comes to the patients. We hear each other’s shit every day.”

“So how did you end up here?”

“I self-committed six months ago. Well, sort of. My folks were embarrassed by me, and the scars, and my ‘downer’ attitude. They felt they couldn’t have friends over, or parties, so they said if I