Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

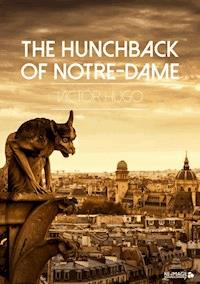

- Herausgeber: Re-Image Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame is a French Romantic/Gothic novel by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. The original French title refers to Notre Dame Cathedral, on which the story is centered. Frederic Shoberl's 1833 English translation was published as The Hunchback of Notre Dame which became the generally used title in English. The story is set in Paris in 1482 during the reign of Louis XI.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 919

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Victor Hugo

Re-Image Publishing

Copyright: This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70 and in the USA

Table of Contents

Introduction

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER I. The Great Hall

CHAPTER II. Pierre Gringoire

CHAPTER III. The Cardinal

CHAPTER IV. Master Jacques Coppenole

CHAPTER V. Quasimodo

CHAPTER VI. Esmeralda

BOOK TWO

CHAPTER I. From Charybdis to Scylla

CHAPTER II. The Place de Grève

CHAPTER III. Besos Para Golpesw

CHAPTER IV. The Inconveniences of Following a Pretty Woman in the Street at Night

CHAPTER V. The Continuation of the Inconveniences

CHAPTER VI. The Broken Pitcher

CHAPTER VII. A Wedding Night

BOOK THREE

CHAPTER I. Notre-Dame

CHAPTER II. A Bird‘s-Eye View of Paris

BOOK FOUR

CHAPTER I. Kind Souls

CHAPTER II. Claude Frollo

CHAPTER III. Immanis Pecoris Custos, Immanior Ipsebe

CHAPTER IV. The Dog and His Master

CHAPTER V. More about Claude Frollo

CHAPTER VI. Unpopularity

BOOK V

CHAPTER I. Abbas Beati Martini bq

CHAPTER II. The One Will Kill the Other

BOOK SIX

CHAPTER I. An Impartial Glance at the Ancient Magistracy

CHAPTER II. The Rat-Hole

CHAPTER III. The Story of a Wheaten Cake

CHAPTER IV. A Tear for a Drop of Water

CHAPTER V. End of the Story of the Cake

BOOK SEVEN

CHAPTER I. On the Danger of Confiding a Secret to a Goat

CHAPTER II. Showing that a Priest and a Philosopher Are Two Very Different Persons

CHAPTER III. The Bells

CHAPTER IV. ’Anátkh

CHAPTER V. The Two Men Dressed in Black

CHAPTER VI. The Effect Produced by Seven Oaths in the Public Square

CHAPTER VII. The Spectre Monk

CHAPTER VIII. The Advantage of Windows Overlooking the River

BOOK EIGHT

CHAPTER I. The Crown Piece Changed to a Dry Leaf

CHAPTER II. Continuation of the Crown Piece Changed to a Dry Leaf

CHAPTER III. End of the Crown Piece Changed to a Dry Leaf

CHAPTER IV. Lasciate Ogni Speranzadc

CHAPTER V. The Mother

CHAPTER VI. Three Men’s Hearts, Differently Constituted

BOOK NINE

CHAPTER I. Delirium

CHAPTER II. Deformed, Blind, Lame

CHAPTER III. Deaf

CHAPTER IV. Earthenware and Crystal

CHAPTER V. The Key to the Porte-Rouge

CHAPTER VI. The Key to the Porte-Rouge (continued)

BOOK TEN

CHAPTER I. Gringoire Has Several Capital Ideas in Succession in the Rue des Bernardins

CHAPTER II. Turn Vagabond!

CHAPTER III. Joy Forever!

CHAPTER IV. An Awkward Friend

CHAPTER V. The Retreat Where Louis of France Says His Prayers

CHAPTER VI. “The Chive in the Cly”

CHAPTER VII. Châteaupers to the Rescue

BOOK ELEVEN

CHAPTER I. The Little Shoe

CHAPTER II. La Creatura Bella Bianco Vestitaeb

CHAPTER III. Marriage of Phœbus

CHAPTER IV. Marriage of Quasimodo

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Introduction

With the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe, the cathedral of Notre Dame figures among the most visited monuments of Paris. Famous for its Gothic facade, great portals, rose window, and looming towers, the cathedral—built principally in the twelfth century—is one of the most enduring symbols of the French capital and its medieval heritage. Aiding in the transmission of the cathedral’s symbolic importance is the novel it inspired: Victor Hugo’s 1831 Notre-Dame de Paris: 1482, better known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame. In it, Hugo brings to life the cathedral of Notre Dame as it existed at the end of the fifteenth century. Many critics and readers have seen the great church as the novel’s true hero, as it takes an active role in the narrative and resides at the core of the ideological message Hugo seeks to project on collective and individual destiny, the passage of time, and the nature of progress. Indeed, Hugo’s novel is perhaps as well known today as the cathedral itself and is, alongside its main characters—Claude Frollo, the fiery priest; Quasimodo, the hideously deformed bell ringer; Phoebus, the golden guardsman; and Esmeralda, the beautiful gypsy girl—firmly implanted in cultural consciousness. From the written page to the stage and screen, the tale has been told and retold countless times, its impact and capacity for reinvention rivaled only by that of another of Hugo’s novels, the ever-popular Les Miserables (1862). If the flurry of recent reprintings and adaptations-including two Disney films and a new musical version—are any indication, generations to come will continue to be enthralled by Hugo’s story of love rendered impossible.

Yet did Hugo set out to immortalize Notre Dame? As much myth surrounds the origin and writing of the novel as surrounds the cathedral itself. If the publicly presented version is to be believed, The Hunchback of Notre Dame was written from July 1830 to January 1831. This account is furnished in Victor Hugo raconté par un témoin de sa vie (Victor Hugo: A Life Related by One Who Has Witnessed It, 1863; henceforth cited as A Life Related), a testimonial written by Hugo’s wife, Adèle, with, as it often has been observed, more than a helping hand from her husband. The novel had been under contract with the publisher Gosselin since 1828, but the theatrical success of Hugo’s play Hernani (1830) distracted the writer from the project. In April 1830 Hugo still had not begun the novel and was threatened by Gosselin with financial sanctions if he failed to deliver the manuscript. A new deadline of December 1830 was agreed upon but was then jeopardized by the political and social upheaval of July 1830, during which the restored Bourbon monarchy was toppled and Louis-Philippe, duke of Orleans, ascended the throne. Consumed by these events and their impact, and additionally troubled by a book of notes that had “disappeared” during his family’s move to a new apartment, Hugo, who had only begun to compose his novel, lost weeks of writing time. Gosselin grudgingly agreed to another extension, pushing back the due date to February 1, 1831. It was at this point, according to Adèle’s explanation, that her husband entered into his novel as into “a prison,” stopping only to eat and sleep. In one of the most famous anecdotes of A Life Related, she recounts how Hugo, upon returning to writing The Hunchback, bought a new bottle of ink. He plunged himself into his work, using this bottle alone, which ran out only on the day he completed the manuscript—January 14, 1831—at the precise moment he marked the novel’s final word on the page. As the story goes, Hugo, reflecting on this “remarkable” coincidence, considered renaming his novel “Ce qu‘ilyadans une bouteille d’encre” (What Is Inside a Bottle of Ink).

This tale of the writing process, and particularly the prodigious circumstances surrounding the novel’s completion, cannot, however, be taken at face value. Even in the early years of his career, Hugo was a master shaper of his own image and rarely failed to seize the opportunity to market himself, to spin reality into legend. The truth behind the composition of The Hunchback is in all likelihood more complex, and is certainly less of a good story. What is clear is that Hugo had a difficult time beginning the novel. Gosselin’s threats were genuine: Hugo had engaged in a contract with the publisher and had received a sizable advance, yet in spite of the rather extensive research he undertook, the manuscript did not materialize. What is also clear is that his recent triumph in the theater kept his attention elsewhere: Not only was Hernani an overwhelming success, but by 1830 Hugo was widely considered the leader of the growing Romantic movement in France. The preface he wrote to his 1827 historical play Cromwell was nothing short of a manifesto that boldly sought to redefine the aesthetics of French theater; it raised the Romantic flag against the constraining tenets of classical drama. Hernani, with its revolutionary use of poetic language and mixture of dramatic modes, put this new vision to the test, and the spectacular polemic that swirled around the play brought Hugo, despite past failures such as Amy Robsart (1828), to the forefront of the theater scene. In addition, poetry (the genre in which Hugo had first distinguished himself by winning, at age seventeen, a prestigious award for his ode on the re-erection of a statue of Henri IV, and which put bread on his table with one of the last royal pensions in the 1820s) continued to occupy him, as did the literary criticism in which he increasingly engaged.

What is less evident in Adèle’s account of The Hunchback’s composition are the events of Hugo’s personal life, which undoubtedly had an effect on his concentration—be they salutary, such as the birth of the couple’s second daughter, Adèle, in late July 1830, or troubling, such as problems in the Hugo marriage that stemmed from his wife’s nascent affair with Hugo’s close friend, the poet and literary critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve. Equally unaddressed—or at the very least underaddressed—is a certain hesitancy on Hugo’s part regarding the genre of the novel. Although writing The Hunchback was appealing in that it would bring money to the growing family’s coffer, Hugo was keenly aware that the novel was generally considered a frivolous literary form. Even as it was already showing by its suppleness to be the genre perhaps best suited to reflect the concerns of the new society born of the French Revolution, and in spite of efforts in the form undertaken in the first decades of the nineteenth century by respected writers such as Benjamin Constant, François-Rene de Chateaubriand, and Madame de Staël, the novel was nonetheless still perceived in the 1820s as a minor genre and lagged in importance far behind poetry and theater, which were both steeped in classical tradition and prestige.

Prior to The Hunchback of Notre Dame Hugo had already written and published three novels—Han d‘Islande (Han of Iceland, 1823), Bug-Jargal (1826), and Le Dernier Jour d’un condamne à mort (The Last Day of a Condemned Man, 1829). Yet each of these examples was more a response to personal or growing social preoccupations than an effort to practice or elevate the genre: Han of Iceland, a Gothic tale of thwarted young lovers, plays out Hugo’s own love story with Adèle (he once said that she was the only person who was meant to understand it). Bug-Jargal, which centers on an episode from the then recent past—a violent 1791 slave revolt in Santo Domingo (present-day Haiti)—had its origins in a school bet in which Hugo was challenged to compose a novel in a period of two weeks. The Last Day of a Condemned Man, a first-person narrative that follows a man through prison to the guillotine, was a polemically charged effort to bring awareness to the horrors of the death penalty. Hugo’s first novelistic endeav ors can be understood as rather isolated attempts to give voice to private or socially oriented concerns. One unifying influence on Hugo’s early novel writing is, however, indisputable—that of the Scottish novelist Sir Walter Scott, author of Waverley (1814), Rob Roy (1818), Ivanhoe (1819), and Quentin Durward (1823). Scott’s mastery of the historical novel brought the genre quickly into vogue and helped, in the 1820s, to advance the merits of the novel as a literary form. Staunch and fervent admirers—among them Honoré de Balzac, the future author of La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy)—declared themselves, and French historical novels, such as Alfred de Vigny’s Cinq-Mars (1826) and Prosper Mérimée’s Chronique du règne de Charles IX (Chronicle of the Reign of Charles the Ninth, 1829), began to appear and garner attention. In the same way that nature inspired introspection and reflection in Romantic poetry, history served as the fertile terrain of the Romantic novel. Whether this renewed interest in French history was the result of reawakened national sentiment or sought to exalt and glorify the ideals of the distant past in an effort to soothe the still-open wounds of the Revolution, the historical backdrop and content lent legitimacy and weight to the form, and was the push the novel needed to propel it forward.

Both Han of Iceland and Bug-Jargal drew heavily on Scott’s expansive vision and his techniques of novel writing, adopting in particular his trademark use of couleur locale—local color—to bring the depiction of the historical period alive through attention to the picturesque. The 1823 preface to Han of Iceland playfully points out the care that went into reproducing the atmosphere of the tale’s exotic location, down to the near-abusive use of the letters k, y, h, and w in the characters’ names. In Bug-Jargal the island of Santo Domingo is also replete with an exoticism produced by vivid details, from the extremes of the tropical landscape to the mysterious language (a mixture of Spanish and Creole) spoken by the rebelling slaves. In a review of Scott’s Quentin Durward that appeared in the July 1823 issue of La Muse française (a periodical Hugo helped found), Hugo openly lauded Scott’s epic and colorful conception of the novel, hailing him as the catalyst of a literary renaissance and praising him for his all-encompassing exploration of the past, for the truth behind his fiction, and for his ability to diffuse a didactic message artfully. Yet Hugo stops short of extolling Scott’s achievements as the apogee of the form; instead he uses his approbation of Scott as a spring-board to elaborate his own conception of the novel. Indeed, despite the critical failure of Han of Iceland, Hugo was in no way deterred from introducing and promoting his idea(1) of a yet non-existent form of the novel: “After the picturesque but prosaic novel of Walter Scott, there remains another novel to be created, more beautiful and still more complete. This novel is at once drama and epic, is picturesque but is also poetic, is real, yet also ideal, is true, but also grand—it will enshrine Walter Scott in Homer” (see, in “For Further Reading,” Victor Hugo, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 5, p. 131; translation mine).

It is this “new” novel that Hugo undertook to create with The Hunchback of Notre Dame, incorporating as organizing principles many of the artistic conceptions already presented relative to theater in his preface to Cromwell, such as man’s inherent duality, the coexistence of antitheses in the universe, the tension between cyclical and progressive notions of time and history, and the essential and prophetic role of the poet-author. Hugo was also aware that this new novel belonged to a new time-both in terms of the political climate following the regime change of 1830, in which the period and the purpose of the Restoration were redefined as a constitutional monarchy came to power; and in terms of the literary climate, as literature was shifting more and more from the patronage model to a business model in which commercial concerns and the emergence of a new and more literate middle-class reading public had, for the first time, an impact on writers and their craft. Hugo’s exclusion of several chapters from the first edition of The Hunchback can be understood in this context. Although Hugo claims in the “Author’s Note Added to the Definitive Edition” (1832) that these three chapters—“Unpopularity” (book 4, chapter 6), “Abbas Beati Martini” (book 5, chapter 1), and “The One Will Kill the Other” (book 5, chapter 2)—were “lost” prior to the printing of the first edition, the truth is more likely that Hugo purposefully held them back to ensure his novel’s commercial success, fearing that the latter two, which are strong in ideological content but do not advance the narrative, might compromise the rhythm of the story. Added incentive for waiting to include these chapters was the realization that the contract with Gosselin specified royalties for only two volumes, and that Gosselin—firm in his stance and already exasperated with Hugo’s delays—would pay no more if Hugo went beyond the agreed-upon length of the manuscript. Retaining them for inclusion in a later edition (with a different publisher once his deal with Gosselin expired) granted Hugo the possibility of maximizing his profit.

Although such reasoning and negotiations may seem commonplace in today’s world, Hugo’s business savvy helped him avoid the financial and artistic dependence on the new reading public that many of his contemporaries faced. Indeed, the novel proved its worth in the 1830s with a number of successes-among them Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and Balzac’s La Peau de chagrin (The Magic Skin, 1831)—increasingly validating the capacities of the form. As realism gradually emerged as the aesthetic and literary movement that would transform the novel into the principal literary genre, and as the serial publication of novels in newspapers spurred on the industrialization of literature, the novelist of the nineteenth century—well known or not-had to live by his or (much less often) her pen, and with this reality often came practical and artistic constraints. In Hugo’s case, however, his careful management of the publication and republication of not only The Hunchback of Notre Dame but also his theatrical works and poetry resulted in a financial independence that ultimately allowed him to avoid the same kinds of concerns about content and style; he could write what he wanted, when he wanted. With regard to his fiction, which subsequently included Les Misérables (1862), Les Travailleurs de la mer (The Toilers of the Sea, 1866), L‘Homme qui rit (The Man Who Laughs, 1869), and Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-three, 1874), this freedom gave Hugo the space he needed to continue pursuing the concept of the novel outlined in his review of Quentin Durward, one in which core, universal truths are transmitted through an expansive exploration of the human condition.

While the majority of French novelists of the nineteenth century who are still read and studied today—Stendhal, Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola—focused their gaze inward on the workings of contemporary society and the ways the political turmoil of their recent past affected their present and the social behavior that defined it, and while the most celebrated French historical novelists, such as Alexandre Dumas—author of Les Trois Mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers, 1844) and Le Comte de Monte Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo, 1844)—looked to the distant past as a way of distracting from the uncertainties of the here and now, Hugo wrote during the course of his career a decidedly different kind of novel. Hugo’s novel viewed history—from long-ago medieval France in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, to the more recent post-Revolutionary and Restoration France in Les Misérables and The Toilers of the Sea, to the seemingly immaterial history of seventeenth-century England in The Man Who Laughs, to the haunting history of Revolutionary France in Ninety-three—as neither an explanation for the present nor an escape from it, but rather as a catalyst for grap pling with ideological and philosophical questions of the highest order relative to the passage of time itself and the nature of progress. Each of Hugo’s novels tells and retells the same story of universal man and his struggles; in this larger context we can understand Hugo’s surprising assertion, in an 1868 letter, that although he considered the historical novel a very good genre because Walter Scott had distinguished himself with it, he had “never written ... a historical novel” (Oeuvres complètes, vol. 14, p. 1;254; translation mine). If, strictly speaking and by modern definition this declaration rings false, since all of Hugo’s novels do meet the criteria to qualify as “historical,” it is more significant that this disavowal—which was made while Hugo was in self-imposed exile in protest of the unfolding history of the Second Empire and its emperor, Napoleon III—underscores the complex understanding of and relationship to history that characterizes all of Hugo’s work.

In The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hugo’s first real attempt to tell this universal story, this complexity finds its ideal expression in the symbol of the cathedral. Firmly planted in the historical moment of the crepuscule of the Middle Ages—the year 1482, as the subtitle to the French edition clearly specifies—the novel showcases one of the medieval period’s great architectural achievements, the cathedral of Notre Dame, which is literally and figuratively at the center of all action (no wonder, then, that Hugo condemned the English translation of the title for shifting the focus from the cathedral to its bell ringer). This choice was undoubtedly affected by the zeal of the Romantic age for all things medieval. Ever since Chateaubriand’s Genie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity, 1802), in which Chateaubriand sought to rehabilitate Gothic art and architecture as well as the Christian faith, there had been a renewed and even frenzied interest in this underappreciated period of history. Hugo himself had jumped enthusiastically on the bandwagon with an 1825 article titled “Sur la destruction des monuments en France” (see endnote 28), in which he calls for an end to the demolition and mutilation of the monuments of the Middle Ages, pieces of a collective past in which history was inscribed. This idea of the monument as living history is developed and magnified in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, as the cathedral serves as the transitional marker both in art, between Roman and Gothic architecture, and in history, between the periods of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Yet this role of the monument as witness bearer, as “carved” history, is destined to be supplanted by the advent of a different kind of record, the printed page.

In “The One Will Kill the Other,” one of the three chapters Hugo reintegrated into the definitive edition of the novel, the narrator seeks to elucidate the enigmatic words spoken by the Faustian priest Claude Frollo, who, during a mysterious visit from King Louis XI, makes, while looking alternately at an open book and the great cathedral, the melancholy assertion that “the book will kill the building” (p. 169). Frollo and the narrator, however, view the relationship between architecture and the written word in quite opposite ways. While Frollo, a high-ranking representative of the Church, laments the invention of the printing press in predicting that it will reduce the Church’s theocratic stronghold, the narrator sees the printing press positively as a democratic invention that will serve to enlighten the masses. Implicit in this notion of inevitable enlightenment are the political dimensions of the more accessible printed word, a form of progress that will propel the masses out of the darkness and tyranny of the Middle Ages. The novel, in which the fictional trajectories and events are shadowed by the major political events of the year 1482—the final full year of the reign of the dying Louis XI—depicts in this way a world on the cusp of change. Using a technique opposite to that employed by most writers of the historical novel, in which the author strives to render time timeless, to transport the reader in a way that makes him unaware of the temporal abyss, Hugo, through his narrator, a man of 1830, repeatedly draws attention to the differences between these two eras, to the great divide between “then” and “now.”

It is the representation of the masses—the people, who are at the height of their religious, judicial, social, economic, and political oppression—that best incarnates the essence of this transitional moment. First seen during Gringoire’s mystery play at the Palace of Justice, the assembled throng (indistinct in its motivations and distinct in its restlessness) has a decidedly moblike quality. This menacing aspect is heightened through the development of the Parisian underworld of “vagrants” (thieves, beggars, vagabonds) in the “Court of Miracles.” The cruelty, superstition, and barbaric ways that govern medieval Paris are mirrored and magnified in this city within the city, presided over by its own ruffian leaders. This group is characterized by its dynamic aspects, by a constant state of motion, yet motion in no way signifies movement in a forward direction or, figuratively, evolution; on the contrary, this group is equally defined by its inherent confusion and blindness. Just as its chosen “Pope of Fools,” Quasimodo, is only “partially made,” the vagrants are without any kind of ideological shape: They are ruled entirely by instincts of base survival and by their own self-interest. At no moment in the novel is this central lack of a guiding ideology more evident than in the scene in which the vagrants storm the cathedral to “save” Esmeralda, as this noble effort quickly degenerates into a frenzied desire to rebel and to pillage the cathedral of its treasures, and results in a staggering loss of lives. At the very heart of the vagrants’ defeat is a chaos rooted in the breakdown of any common linguistic understanding (“There was an awful howl, intermingled with all languages, all dialects, all accents” [p. 410]). Indeed, in an ironic twist that highlights their inability to communicate, the vagrants and Quasimodo work at cross purposes, each believing the other to be the enemy. The vagrants’ capacity to bring about change is dormant, and those not killed in the assault on Notre Dame are quickly brought down by the king’s men.

Yet this effort itself, the bold and subversive action of attacking a church—that is to say, the house of God and, by divine right, that of the king—can be seen as a clear indication of things to come. For while the king succeeds in quelling and even erasing all traces of the vagrants’ failed uprising (the narrator specifies that “Kings like Louis XI are careful to wash the pavement quickly after a massacre” (p. 479), in the larger framework of history another, more significant uprising is referenced, and the potential of this group to bring about change is deferred to a future moment. As Master Jacques Coppenole announces directly to the king, who comfortably oversees the brief mutiny from his apartment above the newly constructed Bastille prison, “The people’s hour has not yet come” (p. 436). This direct allusion to the year 1789—when the French Revolution erupted violently with the storming of that same prison—reminds us that the people will in time become a (political) force great enough to bring down the monarchy. The march of time alone, however, is not enough to ensure progress. Written during the Restoration, a period that sought to turn time backward in wiping out all traces of the Revolution, First Republic, and Napoleonic Empire, the novel is ripe with unease relative to the notion of advancement. Through the numerous narrative interventions that refer the reader to recent or “present” history—including the July Revolution of 1830 (during which Hugo was at work on the novel)—the dangers of blind temporal progress, of the unfolding of one regime into the next, are underscored. While much attention has been given to the shift in Hugo’s political views over the course of his lifetime, from royalist to republican, and of his political engagement (witnessed, for example, by his nineteen-year exile in reaction to the regression of Napoleon III’s regime), progress for Hugo is, above all, ideological. In this way, the memorable dates of 1789, 1793, 1815, and 1830 (and later 1848 and 1870) are all steps on the way to a future sublime moment in which progress would be realized, a moment in which he unfailingly believed but that had not yet come to fruition.

In this conception of history, the roles played by destiny and fate are of capital importance. As the novel’s epigraph informs us, the book is based upon the word anankè (the French rendition of the Greek word for “fate”), which had been “carved” on a wall of one of the towers and was “discovered” by the author during a visit to the cathedral. The word, however, as Hugo signals, has since “vanished,” scraped away into nothingness by time or human effort. The story is thus placed from its outset under fate’s implication of destruction and death, which is further reinforced during the course of the novel by the recurrent image of an innocent fly caught in a spider’s toxic web. Both individual and collective destiny hang under the iron, immutable weight of anankeè, as witnessed by the characters’ trajectories and the social and moral stagnancy that asphyxiates the world of the novel. As we come to learn, it is Claude Frollo, who is at once archdeacon and occult scientist, torn by the impossibility of a different situation (“Oh, to love a woman! to be a priest! [p. 318]), who has traced these letters, but their significance applies to all of the novel’s principal characters, themselves trapped in a web of impossible existence. Frollo loves Esmeralda, who despises him; Quasimodo also loves Esmeralda, who is horrified by the hunchback; and, in turn, Esmeralda loves Phoebus, who, morally bankrupt, is incapable of love. Maternal love and fraternal love are no less spared in this novel of unfulfilled passion: The suffering Paquette is reunited with Esmeralda, her long-lost daughter, only to have the girl immediately ripped away and put to death for her “crimes”; and Jehan Frollo, Claude’s adored brother, who rebuffs his sibling’s affection, meets his death at Quasimodo’s hand during the assault on the cathedral, as Frollo himself will when his “adopted” son holds him responsible for Esmeralda’s death. The oppressive hand of fate operates, by the novel’s close, a mass liquidation of characters—Dom Frollo, Esmeralda, Paquette, Jehan Frollo, and Quasimodo are all dead—while, in a contrast that underscores the irony of destiny, those of mediocre moral substance survive: Phoebus gets out unscathed and marries, as planned, Fleur-de-Lys de Gondelaurier; and Gringoire, perhaps the wisest of all in the area of self-preservation, finds companionship with a goat preferable to the perils of human contact.

To translate this vision of impossible love in an impossible world, Hugo creates a new kind of character to populate his new novel or, at the very least, a different kind of character than the one put in place by his contemporaries. Void of the psychological depth and unity of composition that was increasingly valorized over the course of the nineteenth century, Hugo’s characters, drawn from an archetypal model, are pure symbol. From Esmeralda, who is defined by her sublime state of physical and moral purity, to Paquette, on whom the primal maternal qualities of instinctive love and protection are transposed, to Phoebus, who, as his name implies, is brilliant on the exterior but lacks any true substance, they are larger-than-life representations. The characters of Claude Frollo and Quasimodo are larger than life as well, but they are complicated by the presence of a central duality through which universal man’s struggle is figured. In the case of Frollo, in whom the opposing forces of good and evil engage in a fierce and debilitating combat as he struggles with his growing obsession with Esmeralda, this duality has no possibility for resolution or transcendence: Simultaneously attracted and repelled by the enchanting gypsy, Frollo is the spider and the fly, rigidly trapped in a tortured state between priest and demon. This internal turmoil manifests itself not only mentally, as Frollo loses all interest in his intellectual pursuits and in his much-loved brother, but physically, as Frollo passes during the course of the novel from human to beast to monster, as witnessed by his reaction to Esmeralda’s hanging: “At the most awful moment a demoniac laugh—a laugh impossible to a mere man—broke from the livid lips of the priest” (p. 480). Just as occurs in the alchemy that Frollo investigates, he is literally transformed (changed from one form to another) by the novel’s end, his body, as the narrator notes following Frollo’s fall from the cathedral, found “without a trace of human shape” (p. 483).

In the case of Quasimodo, the central duality is that of the opposing poles of the sublime and the grotesque. From the beginning to the end of the novel, his physical incompleteness leaves him hopelessly suspended between the states of man and animal. Quasimodo is defined by his animal-like strength (proven in numerous scenes such as the early, failed abduction of Esmeralda and the assault on the cathedral) and by his animal-like mentality, which is at once a result of his incomplete intellectual faculties and a conditioned response to the (unkind) way he has been treated by those around him, save his “adopted” father, Claude Frollo, to whom he is completely devoted (“Quasimodo loved the archdeacon as no dog, no horse, no elephant, ever loved its master” [p. 151]). But unlike the archdeacon, who is rigidly locked into his dual(ing) nature, Quasimodo is transfigured by Esmeralda’s simple gesture of kindness to him during his torture on the pillory. All the difference is there. Indeed, from that moment on, Quasimodo undergoes an awakening, during which his dormant soul comes alive and expands exponentially, as witnessed in the scene in which Quasimodo—proud and glorious—swoops down from the top of the cathedral to save Esmeralda from being hanged: “For at that instant Quasimodo was truly beautiful. He was beautiful,—he, that orphan, that foundling, that outcast; he felt himself to be august and strong; he confronted that society from which he was banished ... he,—the lowliest of creatures, with the strength of God” (p. 339). Quasimodo’s devotion to Esmeralda supplants the cherished role previously held for Frollo, and he subsequently does everything in his power to ensure her safety and happiness. In attempting to repair her relationship with Phoebus, in warding off Frollo’s unwanted visits, and in endeavoring to save Esmeralda from the “attackers,” in whom he mistakenly perceives a threat to her safety, Quasimodo risks everything in Esmeralda’s name.

Yet in the end this transfiguration, this conversion from grotesque to sublime—unobserved by Esmeralda, so caught up is she in Phoebus’s aura of false brilliance—is of a profoundly personal nature and passes virtually unnoticed. It is the reader who is charged with recognizing its final expression in the account given in the novel’s last chapter of two anonymous skeletons found sometime later in the vault at Montfaucon, locked in an embrace. Without naming them, the description leaves no doubt that one is Esmeralda (identifiable by the remnants of her white gown and the empty bag that once contained her childhood shoe) and the other is Quasimodo (identifiable by the remains of his hideously deformed body), who disappeared from the cathedral the day of Esmeralda’s death. More remarkable than the embrace, however, is that the male skeleton’s neck is intact, leading to the irrefutable conclusion that he came to the cave not already dead, but to die. The self-imposed nature of Quasimodo’s death thus implies that the completion of this conversion must necessarily occur outside the boundaries of the social and historical world of the novel. For the only place where his opposing poles can be truly reconciled is in the cosmic whole; it is in leaving his shell of a body behind (it significantly crumbles into dust when separated from that of Esmeralda) that this awakened soul can take flight.

This message that redemption and salvation are possible, but never in the world as it exists now, is the thread that binds all of Hugo’s novels together like a quilt whose squares, when viewed carefully, each reveal the same intricate pattern. Everything that is in The Hunchback of Notre Dame will be retraced, retold, rein-vented in Hugo’s four subsequent novels. Quasimodo’s dilemma, his struggle between two opposing poles, will become that of Jean Valjean in Les Misérables, that of Gilliatt in The Toilers of the Sea, that of Cwynplaine—another “monster” horrific on the outside and pure within—in The Man Who Laughs, and that of Gauvain in Ninety-three. Only through their deaths and a corresponding cosmic expansion or rebirth are Hugo’s fictional heroes able to find acceptance, transcendence, reconciliation of their internal oppositions, and affirmation of their individual moral potential. Time and again, the message of Hugo’s “new” novel is that historical existence as depicted, with its blindness, failures, and shortcomings, is incompatible with, or at the very least less significant than, the realization of this personal and often private promise.

In spite of Hugo’s lingering hesitancy surrounding the genre—a thirty-year period of novelistic silence separates the wildly successful Hunchback of Notre Dame from Les Misérables—it is without a doubt the form best suited to the scope and breadth of his all-encompassing vision, one that, to his own mind, was not at all fatalistic. On the contrary, Hugo preferred to view his novels as a “series of affirmations of the soul” (Oeuvres complètes, vol. 14, p. 387; translation mine). While contemporary readers and critics did not always agree—citing The Hunchback of Notre Dame as particularly ambiguous in its meaning—Hugo’s profound and overwhelming belief in both individual and collective man’s potential for progress is perhaps more evident to us today. Indeed, while the inadequacies of each past society that he examines and of the present in which he wrote pervade Hugo’s fiction, his presentation of core, universal truths relative to the human condition show an unwavering faith in the future, in our future, to which his aspirations for the historical and social worlds are deferred.

This continued relevance of Hugo’s vision to our world finds its confirmation in the amazing capacity for reinvention that his fiction has shown, in a resilience that has granted it a life and mythology all its own in popular culture, particularly in the genres of film (Lon Chaney’s and Charles Laughton’s impressive interpretations of Quasimodo come immediately to mind) and theater, in which Hugo’s unforgettable, larger-than-life characters have continued to mesmerize. While this in some ways implies that Hugo’s prediction that the book will kill the monument has been surpassed, and that it is now the book’s turn to be rivaled by and perhaps supplanted by other creative mediums, it is difficult to argue that Hugo would not be in favor of this evolution. During his own lifetime Hugo authorized, encouraged, and even participated in the adaptation of several of his works for the stage (including an 1836 opera based on The Hunchback of Notre Dame), reflecting a desire to give his timeless message the momentum it needed to ensure it an afterlife in fresh contexts and mediums. It is thus that, more than two hundred years after Hugo’s birth, the vision he sought to project has, far beyond the boundaries of the novel, continued to leave its indelible mark on each new generation.

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER I. The Great Hall

Three hundred and forty-eight years, six months, and nineteen days ago today the Parisians were awakened by the sound of loud peals from all the bells within the triple precincts of the City, the University, and the Town.

And yet the 6th of January, 1482, is not a day of which history takes much note. There was nothing extraordinary about the event which thus set all the bells and the citizens of Paris agog from early dawn. It was neither an attack from the Picards or the Burgundians, nor some shrine carried in procession, nor was it a student revolt in the vineyard of Laas, nor an entry of “our greatly to be dreaded Lord the King,” nor even the execution of thieves of either sex at the Palace of Justice. Neither was it the arrival, so frequent during the fifteenth century, of some plumed and laced embassy. It was scarcely two days since the last cavalcade of this sort, that of the Flemish ambassadors empowered to arrange a marriage between the Dauphin and Margaret of Flanders, had entered Paris, to the great annoyance of Cardinal Bourbon, who, to please the king, was forced to smile upon all this rustic rout of Flemish burgomasters, and to entertain them at his own mansion with “a very fine morality and farce,” while a driving rain-storm drenched the splendid tapestries at his door.

That which “stirred the emotions of the whole populace of Paris,” as Jehan de Troyes expresses it, on January 6, was the double festival, celebrated from time immemorial, of Epiphany and the Feast of Fools.

Upon that day there was to be a bonfire at the Place de Grève, a Maypole at the Braque chapel, and a mystery or miracle play at the Palace of Justice. All these things had been proclaimed in the streets, to the sound of trumpets, by the provost’s men, in fine coats of purple camlet, with big white crosses on the breast.

A crowd of citizens with their wives and daughters had therefore been making their way from every quarter, towards the places named, ever since early dawn. Each had decided for himself, in favor of the bonfire, the Maypole, or the mystery. It must be confessed, to the glory of the proverbial good sense of Parisian idlers, that the majority of the crowd turned towards the bonfire, which was most seasonable, or towards the miracle play which was to be performed in the great hall of the Palace of Justice, well roofed in and between four walls; and that most of the pleasure-seekers agreed to leave the poor Maypole with its scanty blossoms to shiver alone beneath the January sky, in the cemetery of the Braque chapel.

The people swarmed most thickly in the avenues leading to the Palace, because it was known that the Flemish ambassadors who arrived two nights before proposed to be present at the performance of the miracle play and election of the Pope of Fools, which was also to take place in the great hall.

It was no easy matter to make a way into the great hall upon that day, although it was then held to be the largest enclosure under cover in the world (at that time, Sauval had not yet measured the great hall of the castle at Montargis). The courtyard, filled with people, looked to the spectators at the windows like a vast sea into which five or six streets, like the mouths of so many rivers, constantly disgorged new waves of heads. The billowing crowd, growing ever greater, dashed against houses projecting here and there like so many promontories in the irregular basin of the courtyard. In the middle of the lofty Gothic façade of the Palace was the great staircase, up and down which flowed an unending double stream, which, after breaking upon the intermediate landing, spread in broad waves over its two side slopes; the great staircase, I say, poured a steady stream into the courtyard, like a waterfall into a lake. Shouts, laughter, and the tramp of countless feet made a great amount of noise and a great hubbub. From time to time the hubbub and the noise were redoubled; the current which bore this throng towards the great staircase was turned back, eddied, and whirled. Some archer had dealt a blow, or the horse of some provost’s officer had administered a few kicks to restore order,—an admirable tradition, which has been faithfully handed down through the centuries to our present Parisian police.

At doors, windows, in garrets, and on roofs swarmed thousands of good plain citizens, quiet, honest people, gazing at the Palace, watching the throng, and asking nothing more; for many people in Paris are quite content to look on at others, and there are plenty who regard a wall behind which something is happening as a very curious thing.

If it could be permitted to us men of 1830 to mingle in imagination with those fifteenth-century Parisians, and to enter with them, pushed, jostled, and elbowed, into the vast hall of the Palace of Justice, all too small on the 6th of January, 1482, the sight would not be without interest or charm, and we should have about us only things so old as to seem brand-new.

With the reader’s consent we will endeavor to imagine the impression he would have received with us in crossing the threshold of that great hall amidst that mob in surcoats, cassocks, and coats of mail.

First of all there is a ringing in our ears, a dimness in our eyes. Above our heads, a double roof of pointed arches, wainscotted with carved wood, painted in azure, sprinkled with golden fleur-de-lis; beneath our feet, a pavement of black and white marble laid in alternate blocks. A few paces from us, a huge pillar, then another,—in all seven pillars down the length of the hall, supporting the spring of the double arch down the center. Around the first four columns are tradesmen’s booths, glittering with glass and tinsel; around the last three, oaken benches worn and polished by the breeches of litigants and the gowns of attorneys. Around the hall, along the lofty wall, between the doors, between the casements, between the pillars, is an unending series of statues of all the kings of France, from Pharamond down,—the sluggard kings, with loosely hanging arms and downcast eyes; the brave and warlike kings, with head and hands boldly raised to heaven. Then in the long pointed windows, glass of a thousand hues; at the wide portals of the hall, rich doors finely carved; and the whole—arches, pillars, walls, cornices, wainscot, doors, and statues—covered from top to bottom with a gorgeous coloring of blue and gold, which, somewhat tarnished even at the date when we see it, had almost disappeared under dust and cobwebs in the year of grace 1549, when Du Breuil admired it from hearsay alone.

Now, let us imagine this vast oblong hall, lit up by the wan light of a January day, taken possession of by a noisy motley mob who drift along the walls and ebb and flow about the seven columns, and we may have some faint idea of the general effect of the picture, whose strange details we will try to describe somewhat more in detail.

It is certain that if Ravaillac had not assassinated Henry IV there would have been no documents relating to his case deposited in the Record Office of the Palace of Justice; no accomplices interested in making off with the said documents, accordingly no incendiaries, forced for want of better means to burn the Record Office in order to burn up the documents, and to burn the Palace of Justice in order to burn the Record Office; consequently, therefore, no fire in 1618. The old Palace would still be standing, with its great hall; I might be able to say to my reader, “Go and look at it,” and we should thus both of us be spared the need,—I of writing, and he of reading, an indifferent description; which proves this novel truth,—that great events have incalculable results.

True, Ravaillac may very possibly have had no accomplices; or his accomplices, if he chanced to have any, need have had no hand in the fire of 1618. There are two other very plausible explanations: first, the huge “star of fire, a foot broad and a foot and a half high,” which fell, as every one knows, from heaven upon the Palace after midnight on the 7th of March; second, Théophile’s verses:

“In Paris sure it was a sorry game

When, fed too fat with fees, the frisky Dame

Justice set all her palace in a flame.”

Whatever we may think of this triple explanation,—political, physical, and poetical,—of the burning of the Palace of Justice in 1618, one unfortunate fact remains: namely, the fire. Very little is now left, thanks to this catastrophe, and thanks particularly to the various and successive restorations which have finished what it spared,—very little is now left of this first home of the King of France, of this palace, older than the Louvre, so old even in the time of Philip the Fair that in it they sought for traces of the magnificent buildings erected by King Robert and described by Helgaldus. Almost everything is gone. What has become of the chancery office, Saint Louis’ bridal chamber? What of the garden where he administered justice, “clad in a camlet coat, a sleeveless surcoat of linsey-woolsey, and over it a mantle of black serge, reclining upon carpets, with Joinville?” Where is the chamber of the Emperor Sigismond, that of Charles IV, and that of John Lackland? Where is the staircase from which Charles VI issued his edict of amnesty; the flag-stone upon which Marcel, in the dauphin’s presence, strangled Robert of Clermont and the Marshal of Champagne? The wicket-gate where the bulls of Benedict the antipope were destroyed, and through which departed those who brought them, coped and mitred in mockery, thus doing public penance throughout Paris? And the great hall, with its gilding, its azure, its pointed arches, its statues, its columns, its great vaulted roof thickly covered with carvings, and the golden room, and the stone lion, which stood at the door, his head down, his tail between his legs, like the lions around Solomon’s throne, in the humble attitude that befits strength in the presence of justice, and the beautiful doors, and the gorgeous windows, and the wrought-iron work which discouraged Biscornette, and Du Hancy’s dainty bits of carving? What has time done, what have men done with these marvels? What has been given to us in exchange for all this,—for all this ancient French history, all this Gothic art? The heavy elliptic arches of M. de Brosse, the clumsy architect of the St. Gervais portal,—so much for art; and for history we have the gossipy memories of the big pillar still echoing and re-echoing with the gossip of the Patrus.

This is not much. Let us go back to the genuine great hall of the genuine old Palace.

The two ends of this huge parallelogram were occupied, the one by the famous marble table, so long, so broad, and so thick, that there never was seen, as the old Court Rolls express it in a style which would give Gargantua an appetite, “such another slice of marble in the world;” the other by the chapel in which Louis XI had his statue carved kneeling before the Virgin, and into which, wholly indifferent to the fact that he left two vacant spaces in the procession of royal images, he ordered the removal of the figures of Charlemagne and Saint Louis, believing these two saints to be in high favor with Heaven as being kings of France. This chapel, still quite new, having been built scarcely six years, was entirely in that charming school of refined and delicate architecture, of marvellous sculpture, of fine, deep chiselling, which marks the end of the Gothic era in France, and lasts until towards the middle of the sixteenth century in the fairy-like fancies of the Renaissance. The small rose-window over the door was an especial masterpiece of delicacy and grace; it seemed a mere star of lace.

In the center of the hall, opposite the great door, a dais covered with gold brocade, placed against the wall, to which a private entrance was arranged by means of a window from the passage to the gold room, had been built for the Flemish envoys and other great personages invited to the performance of the mystery.

This mystery, according to custom, was to be performed upon the marble table. It had been prepared for this at dawn; the superb slab of marble, scratched and marked by lawyers’ heels, now bore a high wooden cage-like scaffolding, whose upper surface, in sight of the entire hall, was to serve as stage, while the interior, hidden by tapestry hangings, was to take the place of dressing-room for the actors in the play. A ladder placed outside with frank simplicity formed the means of communication between the dressing-room and stage, and served the double office of entrance and exit. There was no character however unexpected, no sudden change, and no dramatic effect, but was compelled to climb this ladder. Innocent and venerable infancy of art and of machinery!

Four officers attached to the Palace, forced guardians of the people’s pleasures on holidays as on hanging days, stood bolt upright at the four corners of the marble table.

The play was not to begin until the twelfth stroke of noon rang from the great Palace clock. This was doubtless very late for a theatrical performance; but the ambassadors had to be consulted in regard to the time.

Now, this throng had been waiting since dawn. Many of these honest sightseers were shivering at earliest daylight at the foot of the great Palace staircase. Some indeed declared that they had spent the night lying across the great door, to be sure of getting in first. The crowd increased every moment, and, like water rising above its level, began to creep up the walls, to collect around the columns, to overflow the entablatures, the cornices, the window-sills, every projection of the architecture, and every bit of bold relief in the carvings. Then, too, discomfort, impatience, fatigue, the day’s license of satire and folly, the quarrels caused incessantly by a sharp elbow or a hob-nailed shoe, the weariness of waiting gave, long before the hour when the ambassadors were due, an acid, bitter tone to the voices of these people, shut up, pent in, crowded, squeezed, and stifled as they were. On every hand were heard curses and complaints against the Flemish, the mayor of Paris, Cardinal Bourbon, the Palace bailiff, Madame Margaret of Austria, the ushers, the cold, the heat, the bad weather, the Pope of Fools, the columns, the statues, this closed door, that open window,—all to the vast amusement of the groups of students and lackeys scattered through the crowd, who mingled their mischief and their malice with all this discontent, and administered, as it were, pin-pricks to the general bad humor.

Among the rest there was one group of these merry demons who, having broken the glass from a window, had boldly seated themselves astride the sill, distributing their glances and their jokes by turns, within and without, between the crowd in the hall and the crowd in the courtyard. From their mocking gestures, their noisy laughter, and the scoffs and banter which they exchanged with their comrades, from one end of the hall to the other, it was easy to guess that these young students felt none of the weariness and fatigue of the rest of the spectators, and that they were amply able, for their own private amusement, to extract from what they had before their eyes a spectacle quite diverting enough to make them wait patiently for that which was to come.

“By my soul, it’s you, Joannes Frollo de Molendino!” cried one of them to a light-haired little devil with a handsome but mischievous countenance, who was clinging to the acanthus leaves of a capital; “you are well named, Jehan du Moulin (of the mill), for your two arms and your two legs look like the four sails fluttering in the wind. How long have you been here?”

“By the foul fiend!” replied Joannes Frollo, “more than four hours, and I certainly hope that they may be deducted from my time in purgatory. I heard the King of Sicily’s eight choristers intone the first verse of high mass at seven o‘clock in the Holy Chapel.”

“Fine choristers they are!” returned the other; “their voices are sharper than the points of their caps. Before he endowed a Mass in honor of Saint John, the king might well have inquired whether Saint John liked his Latin sung with a southern twang.”

“He only did it to give work to these confounded choristers of the King of Sicily!” bitterly exclaimed an old woman in the crowd beneath the window. “Just fancy! a thousand pounds Paris for a Mass! and charged to the taxes on all salt-water fish sold in the Paris markets too!”

“Silence, old woman!” said a grave and reverend personage who was holding his nose beside the fishwoman; “he had to endow a Mass. You don’t want the king to fall ill again, do you?”

“Bravely spoken, Master Gilles Lecornu, master furrier of the king’s robes!” cried the little scholar clinging to the capital.

“Lecornu! Gilles Lecornu!” said some.

“Cornutus et hirsutus,” replied another.

“Oh, no doubt!” continued the little demon of the capital. “What is there to laugh at? An honorable man is Gilles Lecornu, brother of Master Jehan Lecornu, provost of the king’s palace, son of Master Mahiet Lecornu, head porter of the Forest of Vincennes,—all good citizens of Paris, every one of them married, from father to son!”

The mirth increased. The fat furrier, not answering a word, strove to escape the eyes fixed on him from every side, but he puffed and perspired in vain; like a wedge driven into wood, all his efforts only buried his broad apoplectic face, purple with rage and spite, the more firmly in the shoulders of his neighbors.

At last one of those neighbors, fat, short, and venerable as himself, came to his rescue.

“Abominable! Shall students talk thus to a citizen! In my day they would have been well whipped with the sticks which served to burn them afterwards.”

The entire band burst out:—

“Oh ! who sings that song? Who is this bird of ill omen?”

“Stay, I know him,” said one; “it’s Master Andry Musnier.”

“He is one of the four copyists licensed by the University!” said another.

“Everything goes by fours in that shop,” cried a third,—“four nations, four faculties, four great holidays, four proctors, four electors, four copyists.”

“Very well, then,” answered Jehan Frollo; “we must play the devil with them by fours.”

“Musnier, we’ll burn your books.”

“Musnier, we’ll beat your servant.”

“Musnier, we’ll hustle your wife.”

“That good fat Mademoiselle Oudarde.”

“Who is as fresh and as fair as if she were a widow.”

“Devil take you!” growled Master Andry Musnier.

“Master Andry,” added Jehan, still hanging on his capital, “shut up, or I’ll fall on your head!”

Master Andry raised his eyes, seemed for a moment to be measuring the height of the column, the weight of the rascal, mentally multiplied that weight by the square of the velocity, and was silent.

Jehan, master of the field of battle, went on triumphantly:—

“I’d do it, though I am the brother of an arch-deacon!”

“Fine fellows, our University men are, not even to have insisted upon our rights on such a day as this! For, only think of it, there is a Maypole and a bonfire in the Town; a miracle play, the Pope of Fools, and Flemish ambassadors in the City; and at the University—nothing!”

“And yet Maubert Square is big enough!” answered one of the scholars established on the window-seat.

“Down with the rector, the electors, and the proctors!” shouted Joannes.

“We must build a bonfire tonight in the Gaillard Field,” went on the other, “with Master Andry’s books.”

“And the desks of the scribes,” said his neighbor.

“And the beadles’ wands!”

“And the deans’ spittoons!”

“And the proctors’ cupboards!”

“And the electors’ bread-bins!”

“And the rector’s footstools!”

“Down with them!” went on little Jehan, mimicking a droning psalm-tune; “down with Master Andry, the beadles, and the scribes; down with theologians, doctors, and decretists; proctors, electors, and rector!”

“Is the world coming to an end?” muttered Master Andry, stopping his ears as he spoke.

“Speaking of the rector, there he goes through the square!” shouted one of those in the window.

Every one turned towards the square.

“Is it really our respectable rector, Master Thibaut?” asked Jehan Frollo du Moulin, who, clinging to one of the inner columns, could see nothing of what was going on outside.

“Yes, yes,” replied the rest with one accord, “it is really he, Master Thibaut, the rector.”

It was indeed the rector and all the dignitaries of the University going in procession to meet the ambassadors, and just at this moment crossing the Palace yard. The scholars, crowding in the window, greeted them, as they passed, with sarcasms and mock applause. The rector, who walked at the head of his company, received the first volley, which was severe:—

“Good-morning, Sir Rector! Hello there! Good-morning, I say!”

“How does he happen to be here, the old gambler? Has he forsaken his dice?”

“How he ambles along on his mule! The animal’s ears are not as long as his own.”

“Hello there! Good-day to you, Master Rector Thibaut! Tybalde aleator! old fool! old gambler!”

“God keep you! did you throw many double sixes last night?”

“Oh, look at his lead-colored old face, wrinkled and worn with love of cards and dice!”

“Whither away so fast, Thibaut, Tybalde ad dados, turning your back on the University and trotting straight towards town?”

“He’s probably going to look for a lodging in Tybaldice Street,” shouted Jehan du Moulin.