8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

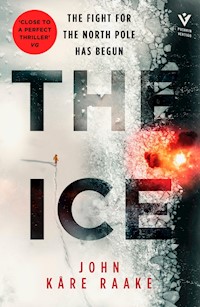

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

READER REVIEWS 'One of the most intense, claustrophobic, fast-paced pieces of work I've had the joy to read in a long time''Tension packed... a fab thriller to kick start 2021 reading''Perfect for fans of the novel Kolymsky Heights, and the work of Martin Cruz Smith''Exciting, engrossing, everything you want a thriller to be. WOW''Perfect chilling winter read' 'Instils a mounting dread... a tale as frigid and punishing as its title' Financial Times A CRY FOR HELPAnna Aune is on a scientific expedition to the North Pole, when the pitch black of the polar night is lit up by a distress flare. A VISION FROM A NIGHTMAREAt a nearby research station Anna discovers a massacre - mutilated bodies strewn about the base. Then, a fierce Arctic storm blows in, cutting off any possibility of escape. A KILLER LOOSE ON THE ICEAnna races to find the murderer before they get to her, but she discovers a secret lurks under the ice - one that nations will kill for...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

5

The North Pole and the regions surrounding it do not belong to any nation, but are a resource that belongs to all the people of the world. China has a population of over one billion inhabitants, one-fifth of the global total, and will use its strengths to participate actively in the development of the Arctic. The battle that certain countries are now conducting in order to gain sovereignty over the Arctic is tantamount to a violation of the interests of every nation on Earth. In light of this new reality, it is difficult to predict the future of “the war for the Arctic”, but the voice of every country must be heard, including China’s.

Rear Admiral Yin Zhuo in an interview with China News, Beijing, 5 March 2010

You never really know your friends from your enemies until the ice breaks.

Inuit proverb

Contents

THE NORTH POLE

November 2018

1

ALL SAINTS’ DAY 89° 35" 7' N—37° 22" 9' W

Each step brought the man from Xian closer to death. It was minus twenty degrees Celsius, not so cold for the Pole, but the northerly wind had increased in strength in the last hour, sending the relative temperature plummeting to almost minus forty.

North Pole explorers have survived temperatures of minus fifty and colder wearing a double layer of wool underwear, windproof outer clothing, and trousers and jackets stuffed with down.

Gai Zhanhai might as well have been naked.

Over his meagre upper body he was wearing only a checked lumberjack shirt, with thin long johns torn above the left knee and green Adidas trainers. The only thing keeping his head and brain warm was his bearskin hat.

Zhanhai knew he was going to freeze to death if he kept running, but also that each step was distancing him from death’s clutches.

From the man hunting him down.

Zhanhai had lost all feeling in his legs. In extreme cold, the torso has to come first, the warm blood being withdrawn from the limbs and skin in order to keep the heart pumping. His legs had developed their own intelligence to anticipate the obstacles in the terrain. They jumped over or skirted around the ice blocks forced up to the surface by the movement of the massive floes. They automatically regained their balance as Zhanhai stumbled on the blanket of fresh, grainy snow under his feet. 10

Green curtains of light billowed in the sky above Zhanhai. The aurora was powerful enough for him to be able to see the contours of the landscape ahead of him. Zhanhai had longed to see the day when the icy landscape would be bathed in sunlight, to experience the North Pole just as his instructors at China’s Arctic and Antarctic Administration’s training base had shown him in pictures.

More curtains cascaded from space, the Northern Lights becoming so strong that Zhanhai feared that it was only a matter of time before his predator spotted him on the flat landscape.

Inside the warm bearskin, his brain sent a pulse of neurons down towards his numb legs, asking them to change course further towards the west. The only plan Zhanhai had managed to come up with as he ran on autopilot through the polar night was to lure his pursuer out onto the ice far enough, then use his superior speed to circle back around to where he had begun.

To the warmth.

To the weapons.

Zhanhai sensed the salty tang in his nose just in time.

He forced his hurried legs to stop before they carried him right out into the Arctic Ocean. From horizon to horizon, a ten-metre-wide crack in the ice had cut a black channel so fresh that only a fine layer of slush had formed on its surface. Ice fog floated up from the pitch-black sea, smothering the Northern Lights in a damp mist.

In half an hour the fracture’s frosty crust would be thick and rigid enough to be crossed on skis. Zhanhai had neither skis nor time.

Except for the clothes on his back, the only thing he had was the flare gun, which, to his amazement, he was still holding in his numbed fingers. He turned his back to the channel and raised an arm so that the gun aimed towards the tracks his Adidas shoes 11had made in the newly fallen snow. The tracks the hunter would follow to find him.

Before him, Zhanhai saw huge slabs of ice strewn like enormous, grey pieces of candy in the murky landscape. He could see no movement between them.

Zhanhai’s arms had begun shivering so much that he barely managed to keep hold of the flare gun. From what his Arctic instructors had taught him, he knew his body would soon lose the tension pulling together the veins that kept the blood in the warmer parts of the body. When this happened, warm blood would run back down to his ice-cold arms and legs. The cold would cool the blood down to a viscous soup. When the chilled blood returned to the heart, its muscles would beat slower, leading to less blood reaching the brain. It would eventually cease to function. Hallucinations would follow. What was left of the blood circulating under his ice-cold skin would begin to feel far too warm. He would be consumed by an urge to start taking off his clothes.

Then he would die.

He decided to retrace his own footsteps in the hope that his pursuer had got lost in the darkness of the ice desert. In the same instant, Zhanhai heard the splash.

If Zhanhai had made that decision a couple of seconds earlier, perhaps the polar bear would not have been able to reach him.

Not that it would have altered the outcome.

An adult polar bear can run at a speed of over thirty kilometres an hour for short distances. Even faster if it is famished and lean. This young female, now bursting out of the water like a live missile, had not eaten for weeks.

Its powerful front claws swung out at one of Zhanhai’s calves, flaying his ragged long johns and morsels of frozen skin and sending him spinning to the ground. Zhanhai felt neither the cold from the ice nor the jagged crystals cutting into his face as 12he was thrust across the snow. His body had long since switched off such unnecessary, energy-sapping senses. The optic nerves in Zhanhai’s eyes, however, registered the bear’s maw as it gaped before him. Four long canine teeth. A row of small, sharp molars. A blood-red tongue. His pupils barely had time to send these impressions to his brain before the polar bear locked its jaws around his head. Zhanhai’s skull split, pieces of his brain spraying out over the ice.

In his death throes, his spinal cord sent billions of unsynchronized nerve signals out along the body’s neural pathways. One of these reached through the frozen nerve endings all the way to the fingertip of the hand holding the flare gun.

Zhanhai was already dead when his finger twitched, pulling the trigger. The flare gun’s hammer struck the primer of the cartridge loaded in the steel barrel. Its propellant chamber exploded, the pressure from the gases launching the flare skyward.

The flare burned a stripe deep into the bear’s fur as it shot past. The carnivore dropped Zhanhai’s crushed head and fled back to the channel, diving in and breaking a hole in the crust that had already begun to form on the surface of the sea. The waves beat the thick ice particles towards the edge, where they were immediately stiffened by the cold.

Held aloft by its parachute, the flare burned brightly high up in the sky, casting a red glow on the icy landscape where Zhanhai’s battered body lay—a fleeting vision of hell.

2

89° 33' N—37° 43' W

“Fuck.”

Anna Aune sat up in bed. Her left arm was freezing. It had slipped out of the sleeping bag while she slept and had ended up lying against the outer wall of the hovercraft, Sabvabaa. The wall was always ice cold due to the draughts that entered through the poorly sealed window above her bed. She should have changed the seal, but the nearest parts dealer was 1,300 kilometres away and the only way to get hold of anything was to have it carried by transport plane all the way from Norway to the North Pole, then thrown out attached to a parachute. So, it was just easier to try sleeping with both arms inside the sleeping bag.

Anna stuck her hand in under her thermal jersey. Under the cold tips of her fingers, her heart was beating. The daily medical check: Anna Aune was still alive. The hands of her watch glowed in the dark: 23:13. She had no idea what had woken her up, and no clue when she had fallen asleep. Without sunlight as a guide, all the days at the North Pole blended into one.

She yawned and glanced out through the frost crystals on the window, just catching a glimpse of the reflection of her rangy body, like a larva, inside the tight sleeping bag. A red star shone in the sky. Fucking huge, she thought. A supernova. Anna blinked and rubbed her eyes. The star was still shining. She pressed her nose against the cold glass to see better, holding her breath so that the damp air from her lungs wouldn’t form even more ice on the window. Now Anna could see something above the red star. 14White smoke, and a parachute. Then she realized that what she was seeing out of the window wasn’t a dying star.

It was a flare. The sight of it got her nervous system pumping adrenalin into her blood. She knew all too well what these things meant.

Danger.

Death.

Everything she was running from.

Anna sat completely still. She could hear the whistling of the wind in the antennae on the hovercraft’s roof but clung to the hope that she was still sleeping, that she was in the middle of a hyperrealistic dream and didn’t even know it. The serenity of the North Pole and the absence of sights and sounds had got her dreaming again, or, at least, now she could remember what she dreamt.

Anna was far from keen to wake the man sleeping at the other end of the cabin, but since she’d studied the flare long enough to realize that it wasn’t an illusion, instinct took over.

“Daniel, wake up!” she heard herself shout.

Professor Daniel Zakariassen, asleep on the other side of the curtain that divided the hovercraft’s cabin at night, grunted softly. The bed creaked as he turned over. The old man was a heavy sleeper.

Anna stood up out of bed, pulled the curtain to one side and stepped past the worktable where three laptops hummed quietly, crunching the data streaming up from instruments at the other end of kilometres-long cables beneath the surface.

“Daniel, I see a flare!”

She shook Zakariassen, who startled and sat up. A hint of rosemary hit her. He swore by camphor drops to keep colds at bay, even though on the ice there were no viruses other than those they had brought along with them.

“What is it?” he said, his voice thick with sleep. 15

“I can see a flare.”

“Flare… now?”

His words sounded even more clear-cut than usual. Zakariassen was originally from Tromsø, but his northern lilt had adapted to the dry language that prevails in science’s ivory towers.

Anna walked up to the large windows at the front of the cabin. The red flare had dropped in the sky, but was still clearly visible.

“The position, have you been able to fix the position?” shouted Zakariassen.

“No.”

Zakariassen tramped past her and wiped away the condensation on the instrument panel’s large compass. He mumbled something that at first she didn’t hear.

“Distance?” he repeated. “How far away is it?”

Anna tried to estimate the distance. The flare was hanging directly above the short pressure ridge of icy rubble that had been pushed up from the pack ice in crunching, rumbling birth pangs more than two weeks ago. There was a pair of rangefinder binoculars in a bag under her bed, but the flare would probably vanish by the time she pulled them out. Her quick fix was a simple Girl Scout trick.

She closed her right eye and stretched out her arm in front of her with her thumb trained on one of the peaks on the pack ice. When she switched eyes, her thumb shifted in her field of vision two peaks further to the left. She estimated the distance between the first and the second peaks to be around four hundred metres. The trick was to multiply this distance by ten. The frozen peaks were four kilometres away. The flare looked to be even further back.

“At least four, maybe five kilometres,” she said.

Even though it was her own voice, Anna felt as if she were having an out-of-body experience. All she wanted was to go back 16to bed, pull the hood of her sleeping bag over her head, and dream on.

Zakariassen took out a little case. Inside there was something that looked like a clunky, old-fashioned video camera. “I’ll see if I can see anyone in the thermal imaging camera.” He turned it on, holding it out in front of him. On a little screen at the back, Anna saw the icy dark now depicted in blue shapes. The only thing that wasn’t shaded blue was the flare, which glowed bright red on the screen too. The professor swept the camera back and forth, but out on the ice nothing else was radiating heat. He put the camera back in its case and sat down in front of a computer.

As he pushed up his glasses, the lenses magnified the deep wrinkles in his forehead. A map of the North Pole appeared on the screen as he woke the machine from its slumber. The professor set his thin fingers on the keyboard, punching numbers onto the white landscape.

“Five kilometres, 89 degrees… 35 minutes, 7 seconds north… 22 minutes… 9 seconds west. It doesn’t make any damn sense, I have no record of anything at that position.”

In her previous line of work, Anna’s rigorous training had drilled into her the crucial importance of knowing the theatre of war. Understand the terrain. Always be ready to engage the enemy, but keep a back door open in case of the need to beat a hasty retreat. Zakariassen was right: nobody was supposed to be at the position the flare was coming from. That meant that whoever had fired it must have come from the only other inhabited place for hundreds of kilometres in any direction.

She took a deep breath. It had to be the Chinese.

3

“Ice Dragon,” said Anna loudly. “The flare must have been fired near the Ice Dragon base. The bearing is right. The Chinese drift station is there—it must be seven or eight kilometres north of us.”

She looked out of the window. The flare was about to drop down behind the ice mounds. The horizon was outlined brightly in red, as if streaked in blood. She had seen these signs before, burning above an unknown town. A plateau. A mountain beneath a distant sky. The warnings were always the same.

War comes in many guises.

This one began with an innocuous suggestion over an old seventies kitchen table with a view over Tromsø and the surrounding fjord.

“There must be hundreds of students who would jump at the chance of an expedition to the North Pole, though?” was Anna’s first objection when her father, Johannes Aune, suggested that she might be a suitable expedition partner for Professor Zakariassen.

“Of course.” Her father hesitated a little. “People are interested and Daniel has spoken to many of them, but there’s probably something not quite right with any of them. Daniel is… a little odd. It could be good for you too, Anna.”

She hadn’t bothered to ask her father what psychological insights convinced him that it would be a good idea for his thirty-six-year-old daughter to spend nine months drifting on an ice floe across the North Pole with a difficult, seventy-three-year-old widower she had barely seen or spoken to in the last fifteen years. 18

Johannes Aune had grown up on the same street as Daniel Zakariassen in Tromsø. Daniel was bright and gave private tuition to fellow pupils who were dropping behind in their grades. One of these was Anna’s father, who sorely needed a pass in Norwegian to get onto a course in mechanics at the technical college. In Johannes, Daniel recognized a natural gift for engines and engineering that, over the years, brought the theoretician and the mechanic together as close friends. The scientist paid Johannes a visit whenever he needed to build a scientific instrument, and the mechanic came to Daniel with a shopping bag full of receipts when it was time to submit his tax return. It was Johannes who had proposed a North Pole expedition as the brilliant finale to an otherwise anonymous career.

“Daniel needs this,” her father said, as his nicotine-yellow fingertips fidgeted with the old pack of cards with which he would play solitaire before breakfast TV began. “After Solveig died, you know… he’s got nothing.”

“Dad, I’m not a therapist.”

He stood up, taking two of the fragile cups that Anna’s mother had inherited from her Russian babushka out of the cupboard above the sink, and picked up the jug from the worn-out coffee machine.

“There’s not much time, you know. Daniel got the last sponsor on board yesterday. Almost three million kroner from a research institution in Switzerland. But they need him to leave for the ice now. Daniel’s a theorist, a smart guy with numbers and that kind of thing, but he needs someone to look out for him. You’ve been out in a long, cold winter before,” he argued as he poured the coffee.

“I’m not so keen on the cold these days,” Anna said, taking a sip of the bitter coffee.

“Yes, but you’ve been through training in the Special Command… all the military exercises you’ve been on up here. You know how to survive in Arctic conditions.” 19

For a second Anna thought about snapping back at him with a wisecrack that, above all else, she was best at making sure that others didn’t make it home. But she bit her tongue. He was only trying to help. These last two years had been tough on him, too.

A call from the Armed Forces Special Command at its base in Rena had woken Johannes up in the middle of the night. “Your daughter has been seriously wounded in action in Syria,” was the brief message. “We don’t know whether she is going to survive or not.” An hour later, Johannes was sitting in a black car with the Special Command insignia on its door. On the way to the airport in Tromsø, the car picked up Anna’s half-sister, Kirsten, from the comfortable neighbourhood on a hill above the city where she lived with her husband and their three children.

They were taken to the airport from where a jet usually reserved for the chief of defence, the prime minister and the king flew them straight to a military airbase in Germany. From there a helicopter from the German Air Force delivered them to the American military hospital in Landstuhl. When her father and sister came in to see her, Anna was lying unconscious in a hospital bed with tubes feeding her oxygen and nutrition. She had been placed in an induced coma to give her body a chance to recover after suffering three heart stoppages over two operations. The doctors explained she had been hit by a powerful projectile that had travelled through her body, from the shoulder down to the hip.

After watching over Anna for a week without her regaining consciousness, Kirsten had to return home. She had a family and a business to take care of. Johannes Aune stayed on at the hospital in Landstuhl for two months. At home in Tromsø, three employees made sure that Aune Motorworks stayed afloat. Two weeks after she was admitted to military hospital, the doctors woke her up.

The first words she said to her father were “Yann’s dead”. Johannes had cried with joy that his daughter had survived. Anna cried in sorrow for the same reason. 20

A month later, Johannes pushed his daughter in a wheelchair into reception at Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital at Nesodden, outside Oslo. After six months of painful treatment there, she was able to walk again. That same day, she took a taxi down to the quay from where the ferry sailed towards Oslo. When the Nesodden ferry docked at Aker Brygge, she walked a few hundred metres to an anonymous office to meet Victoria Hammer, who, many years ago, had recruited her into E 14, a secret military unit whose existence was known only to a select few. Victoria tried convincing Anna not to quit her job. She failed.

Since then, Anna had been living in her old room at her father’s house. In the end, and as an excuse not to make a decision, she agreed to join Daniel Zakariassen’s expedition. An excuse to avoid the hassle and the many good suggestions about what she should do with her life. An excuse to postpone her return to the world and a fresh start in life. Zakariassen’s hovercraft would drift on an ice floe towards the North Pole, even further away from civilization.

Anna saw her reflection in the hovercraft’s window. Her dark hair hung down over her forehead like a tired old mop. Her skin was pale, her eyes mere black hollows. Her cheekbones cast long shadows, like a vampire with a serious case of iron deficiency, she thought.

The loudspeaker on the radio transmitter crackled. “This is ice drift station Fram X calling ice drift station Ice Dragon… over!”

Zakariassen was leaning in towards the microphone, speaking slowly and clearly, following radio protocol. His English was sharp and clipped, but heavily accented.

“This is the hovercraft Sabvabaa, the Norwegian Fram X expedition calling Ice Dragon operating base. Are you receiving us? Over.” 21

Anna noticed a green light burning through the reflection of her face. The long, billowing curtains of the Northern Lights glimmered in the cosmic wind blowing in from space. Unusually powerful solar storms had been interfering with their communications all week.

The University of Tromsø had warned them that several satellites were out of action due to the storms. The professor had pointlessly slammed the palm of his hand against the computer’s monitor when his weekly sponsors’ report bounced back from space. Server not found.

Anna had been more annoyed about the new episode of The Big Bang Theory that she was missing out on.

“Fram X expedition calling Ice Dragon. Are you receiving us? Over.”

Zakariassen listened to the scratching of the loudspeaker. “Fram X expedition calling Ice Dragon. Are you receiving us? Over,” he repeated.

“I’m calling Boris,” Anna said.

4

“We can’t get through to Ice Dragon either,” said Boris.

The Russian’s deep baritone came and went with the flickering of the Northern Lights. In Anna’s mind, the voice evoked a picture of a short, fat man trapped in an even more cramped space than she was.

“Is there a problem?” she asked.

“Not before you rang, Anna,” he answered, laughing out loud.

“They haven’t issued a Mayday…”

Anna was hoping that Boris would offer to take care of it. That this was a matter for the Russian authorities.

Boris was a meteorologist stationed on the Taymyr Peninsula, at the northernmost tip of Siberia. He chatted with Anna daily as he sent out his weather and ice reports. Since she received satellite images and the reports by email, it was not really necessary, but Boris liked to chat.

The Russian became even more eager when he realized that Anna was interested in classical music, a legacy passed down from her mother, who loved film scores and was always playing the piano. She absolutely had to come to his home city of St Petersburg, Boris insisted. He would be her guide and take her to concerts, the opera and the ballet.

Sometimes she wondered how a middle-aged man from St Petersburg with a taste for the finer things in life had ended up in one of the most desolate places in Russia. Had the connoisseur been having an affair with the wife of a university director? Embezzling funds? Fooling around with young boys? She thought 23about all of this because she, too, had banished herself to a place found on no map; the ice never stood still long enough for one to be drawn.

Daniel reached out his hand, motioning for the satellite phone receiver. Anna held it out for him to speak into.

“Have you spoken to CAAA?” he asked.

Boris wasn’t laughing any more.

The Chinese Arctic and Antarctic Administration was far from popular with the Russians. China didn’t border the North Pole, but that hadn’t prevented them from asserting their claim to the resources beneath the ice. To demonstrate this, they sent the icebreaker Snow Dragon, or Xue Long as it was called in Chinese, to the North Pole at regular intervals. The Russians took exception to the flame-red steel giant anchoring at the pole, directly above the Russian flag they had planted on the ocean floor.

“The Chinese are struggling with the solar storms too, but the Yellow River base on Svalbard was in contact with the commander of Ice Dragon a couple of hours ago. It was a fucking terrible connection. Give them some time.”

Anna looked out of the window. She was surrounded by pitch-darkness. The flare had vanished for ever.

“It might have been an accident. The Chinese might have mixed up the dates and thought it was New Year. Set off some fireworks. Shit happens,” said Boris.

It was late and Boris’s baritone was husky with vodka. His English sounded like a dissonant Mussorgsky symphony, touched by genius and drunken madness.

“What I saw was no firework. Can you send a helicopter?” Anna yelled, so loud that Boris would hear it through the interference created by the solar storms.

“Yes, when the winds have calmed down tomorrow—if the Chinese ask for help.” 24

“How bad is the wind going to be?”

“Nooot good… up to seventy-five kilometres an hour. Gusting to storm force.”

Zakariassen grabbed the receiver and pressed it against his ear.

“It’s not blowing so much over here yet.”

Boris’s laughter crackled through. “Well, call me in two to three hours and tell me who’s right.”

“Sabvabaa will get to the Ice Dragon base in two hours, no problem,” said Zakariassen firmly as Boris broke off the connection. “We’re the only ones who can help the Chinese if they’re in trouble.”

“How do you know we’ll be able to ride out the storm?” asked Anna. The Northern Lights had vanished and outside total blackness reigned. She switched on the searchlight on the roof of the hovercraft, turning the lamp so that the light hit the weather station standing out on the ice. The wind vane was already spinning at a clip.

“Sabvabaa has endured the winter before. Her hull can take it,” replied Zakariassen.

“The Americans have a base on Thule. With their helicopters they’ll get there quicker from Greenland than we can.”

The professor had to admit that Anna had a good point, but when Zakariassen finally got through to the duty officer at 821 Air Base Group on Greenland’s west coast, he was given the same message. If the Chinese thought there was an emergency situation at their base, they would have to ask for help formally. And the conditions were too bad right now. Even if the American rescue helicopters could fly to the North Pole, they would not be able to land in the storm that was making its way in from the Russian tundra.

Before the final decision to cast off was taken, Zakariassen called Sabvabaa’s owners, the Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center in Bergen. The head of the institute shared Anna’s 25concerns for the coming storm, but agreed that they were obliged to offer help. Zakariassen was given permission to go. Anna heard Zakariassen start the hovercraft’s engine as she pulled on her clothes behind the curtain, a flowery tablecloth she had borrowed from her father’s house. The hovercraft rattled and shook as the engine idled erratically.

As she swiped a stray tangle of hair away from her mouth, it revealed a narrow scar on the side of her face. It cut across the skin straight down towards a larger scar that was just visible over the neck of her thermal vest. Above the scar on her shoulder, the lobe was missing from her right ear. The visible traces of the bullet that had almost killed her in Syria.

She quickly pulled on her thermal underwear and, on top of that, another layer of clothing. As she yanked down the curtain, she saw the professor on his way out of the hatch.

“I’ll start clearing things away outside. Come when you’re ready,” he shouted, opening the hatch all the way. The wind blew straight in and the cabin temperature dropped quicker than a lead weight on its way to the seabed. Zakariassen switched on his headlamp and crawled out into the blizzard.

Anna’s head nearly touched the ceiling of the cramped cabin. A single step brought her to her survival suit, which was hanging on a peg above a gas burner and a kettle. Next to the burner was a samovar, a large, beautifully decorated Russian tea kettle, much too big, really, for this little cabin, but a departing gift Anna had not been able to refuse. It had been given to her by Galina, the Russian woman Johannes had employed when he began renting out rooms to tourists in his large, Swiss-style house, beautifully located next to the Tromsø straits.

“My father made tea for tourists with this samovar when he was a conductor on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Nothing like strong, sweet tea when it’s cold,” Galina said, before giving Anna a kiss on each cheek and waving goodbye at the airport. 26

After three weeks at the North Pole, Anna agreed. There really was nothing like steaming-hot, sweet tea to get the body moving. But now it would have to wait. She pulled on the fluorescent-yellow survival suit with reflective stripes over the chest and knees and stepped into a pair of blue moon boots. The North Pole was no place for fashion junkies.

She got dressed in silence. Only the slight sound of her breath and the creaking of her shoes on the wooden floorboards could be heard above the engine’s hum. As she opened the hatch outwards, the Arctic wind bit in fury.

A warning of the storm that was yet to come.

5

Anna saw Zakariassen standing some distance away. He was disconnecting the cables that lay in coils on the ice from their instruments—the very reason they were at the North Pole. Or, to be more precise, the reason that Daniel Zakariassen was at the North Pole.

Most of the instruments were coupled to long cables hanging thousands of metres down into the ocean. Delicate sensors could capture the sound of seals in the water, or the echoing cries from a school of beluga whales looking for a breathing hole. Other instruments hung right in the middle of the ocean’s invisible highway, the currents beneath the surface. When the first measurements came in it didn’t take Zakariassen long to conclude that the ocean temperature had risen and the salt concentration was lower than the previous year.

He explained to Anna that the fresh water from the ice melt diluted the ocean’s salt content, weakening the currents sending cold water from the north down to the equator, where the seawater would evaporate, cooling down the atmosphere. When this declined, the temperature in the entire atmosphere increased and the air over the North Pole also became warmer—on one random November day in 2016, an incredible twenty degrees warmer than usual. Now the very backbone of the North Pole itself was beginning to melt—the ancient, hard blue ice that had always lasted from one year to the next.

“Your children are most likely going to be the first for three million years to grow up without ice at the North Pole,” sighed Zakariassen late one evening after having published the first expedition blog on Fram X’s website. 28

“Lucky that I wasn’t planning on having kids, then,” was Anna’s terse reply.

She closed the hatch behind her, walking into the headwind across the hull of the hovercraft, and jumped down onto the ice. Zakariassen motioned for her to come over to him.

“I just have to fix something.” Her words drifted away with the wind, but Zakariassen had heard enough, and waved both arms to stop her.

“No, we have to get moving before the storm hits.”

Anna ignored his protests and walked quickly past the large propeller at the rear of Sabvabaa and deeper into the dark. She let the light from her headlamp lead her along the poles stuck at regular intervals into the ice. Between them tripwires were strung, almost invisible, that would trigger a flare at the top of each pole if an intruder walked through them. In this corner of the world, that intruder was usually a polar bear.

The light from her headlamp struck a rise in the ice. Anna walked over to it and dropped to her knees. She pulled off her gloves and blew warm air onto her frozen fingers, then brushed away the snow covering the block of ice that she had buried earlier in the day, it being 1st November. The Day of the Dead. All Saints’ Day. Beneath the snow a photograph became visible, frozen in time inside the ice block.

It was a picture of a man.

The man was standing under a blue sky, his eyes prominent in his tanned face. Wrinkles streamed out from their corners, like cracks in an ice floe, above a blinding white smile. In the curls of his black hair, some grey strands twisted over his ears, betraying that he was perhaps older than he looked. He was dressed in a light-blue jacket, and an illegible ID card hung over his chest.

Anna pulled something out of the snow in front of the photograph. It was a grave lantern, its flame extinguished. She screwed 29off the lid and shone a light down into it. The wick was covered in snow that had found its way in through the ventilation holes in the top. She tipped it upside down, shaking the snow out, then lit the wick with a well-worn Zippo with an engraving of a winged dagger on its side. When Anna was completely sure that it was burning strongly, she dug a hole in the snow all the way down to the ice sheet and placed the burning lantern inside. Now it was sheltered from the wind.

She stayed on her knees looking at the picture. Illuminated by the lantern, a halo of light encircled the man’s face, its flickering flame bringing his eyes to life. His name was Yann Renault. He and Anna had been together for almost a year when he was kidnapped by IS in Syria on an assignment for the aid organization Médecins Sans Frontières. It was supposed to have been their final posting. Anna would move to the village of Seillans in the mountains of Provence, where Yann’s parents ran a little hotel. The plan was that they would take over the hotel when Yann’s parents retired. But if you want to make God laugh, tell him about your plans.

Yann Renault was buried at the cemetery in Seillans while Anna was lying in a coma at the hospital in Germany. To the world, Yann was a hero who had sacrificed his life to spare his fellow hostages. Only a handful of people knew that it was Anna Aune who had saved them. Even fewer still knew what had really happened when Yann was killed.

She pulled back the stiff sleeve of her survival suit to reveal her watch. The hands were ticking over, breaking free from midnight. All Saints’ Day was over. The dead had been remembered. The machinery of the world ground on.

When Anna climbed back into Sabvabaa’s cabin, Zakariassen was sitting in the driving seat with his hand resting on the wheel. He had an irritated look on his face, but refrained from commenting on the delay. She turned around and glanced out of the hatch at 30the metal equipment cases on the ice. Forty cases with everything they needed to survive for almost a year. A year without having to think about anything other than work, eat, sleep. Now more than ever, sleep seemed like the greatest of earthly pleasures.

“The ice floe may break apart while we’re away,” she said.

Zakariassen looked at her.

“If that happens, you’ll lose all your equipment,” she continued. “Your expedition will end in complete failure.”

The old man looked at her for a few moments before his eyes flitted away, fixing themselves on a point on the wall in front of the worktable. Several moments passed before he shook his head firmly, and placed his hand on the throttle.

“We have a duty to help people in distress,” said Professor Zakariassen in a firm voice, shoving the throttle forward.

6

In the Inuit language, sabvabaa means “flows swiftly over it”, but as Anna sat next to Zakariassen she couldn’t help thinking that “bumps slowly over it” would be a better description of their progress.

The wind had increased in strength and, in order not to lose control, Zakariassen was driving well under the normal cruising speed of twenty-five knots.

Sabvabaa hovered over the ice on a cushion of air trapped under the hull by its heavy rubber skirting. Although the air cushion meant fewer obstacles, and Sabvabaa floated easily over blocks of ice and open fractures, the lack of friction beneath her was also a problem when the wind hit her from the side. Zakariassen constantly had to adjust his course with the steering wheel, which controlled the rudders on the large propeller driving the hovercraft forward. Sabvabaa was lurching forward like an inebriated wino, and every time Zakariassen increased or decreased the power, Anna sensed a slight nausea rising in her throat.

She took a deep breath and tried to look straight ahead. Snowflakes whirled into the lights like white moths on a warm summer night. An image as far away from reality as it was possible to be. Her fingers were still ice cold, and a thermometer on the instrument panel told her that the temperature had dropped to minus thirty in the short time since she had seen the flare. She felt the seat shake, heard the rattling of objects in the cabin hitting each other. A faint stench of diesel. Outside, the North Pole was pelting the windscreen with ever more snow. She was trying to 32focus, trying to imagine what had happened at the Chinese base, and what they would find when they got there, but the monotonous rumbling of the engine kept skewing her concentration.

Back to the picture of Yann still lying on the ice.

Anna remembered precisely where the photograph was taken.

In Syria, at a refugee camp on the outskirts of Ain Issa, two years, six months and twenty-two days ago. Yann had invited her to see how everything was going with the boy who had brought them together. Little Sadi had laughed when Anna leant over the cot he was lying in. Tiny bubbles of gurgling delight slipped out of the corners of his mouth. He was seemingly unconcerned that he had lost one leg below the knee. A brutal reminder that the Syrian civil war didn’t care whether its victims were soldiers or children.

“Sadi’s going to be fine. Kids get used to prostheses much quicker than adults,” said Yann as they ate lunch in an air-conditioned tent afterwards. This first meal together was what Yann would later insist was their first date. Anna always denied it with equal fervour.

“I know I’m not the most romantic person on the planet, but driving two hours across a scorching desert to a miserable refugee camp, eating something you called lunch from a plastic plate—all while your colleagues argue in French and stick their elbows in my food—is no date, not in Norway. Not even in Tromsø.”

Yann always laughed, kissing her. “You don’t know what romance is, Anna. You must be pretty glad you met me otherwise you would never have melted, my Scandinavian ice queen.”

Now Yann was dead and she was, seemingly, queen of the ice again. Anna knew that she would never meet anyone who could match up to the self-assured, romantic man from the mountains of Provence again. This knowledge had rushed in, filling every cell of her body the moment she woke from the coma at the hospital 33in Germany. No matter what her father said, no matter how her colleagues consoled her, or what a succession of psychologists tried to get her to do to move on, she saw no meaning in life any more. The only reason she was still alive was that she couldn’t bear the thought of her father finding her dead. Anna had agreed to go to the North Pole, but not that she would come back.

“Are we on the correct heading?”

She was dragged away from her thoughts as a gust of wind blew Sabvabaa hard into a sideways lurch. She scarcely managed to grab hold of the computer she had on her lap before it slid onto the floor. The clock on the screen showed it had been almost thirty minutes since they had set out for the Chinese base. The laptop display was a satellite image with three moving dots. She knew that the red one was Ice Dragon’s position. The blue one was Sabvabaa, and the green one was the GPS transmitter on the equipment they had left behind on the ice. Sabvabaa was midway between the red and the green dots. On the satellite image Anna saw dark veins in the ice. The fractures that lay ahead of them.

“Yes, we should see the base soon.”

Zakariassen throttled up.

The kitchen cabinets rattled behind them as the vessel lurched onwards. Slush sprayed up, splattering the windows as they passed over a broad channel.

“Fuck!”

Zakariassen flung Sabvabaa sideways as a huge pressure ridge appeared in the searchlight’s beam. The hovercraft began to slide and Anna watched the shards of the towering wall of ice approaching at high speed. White floes. Black shadows. Razor-sharp contours.

Red lights flashed on the instrument panel and an engine warning screeched hysterically as Zakariassen applied full power. 34He wrenched the wheel steering the propeller, barely managing to force the boat away from the icy barricade.

“Jesus, Anna, stay focussed!” he barked furiously.

Her heart thudded in her chest and she could hear her pulse pounding in her ears as she saw the jagged edge of the ice wall drift past the windows like the spikes of an enormous hedgehog. Her eyes scanned the instrument panel. Something was wrong.

“It might help if you turned on the radar,” she said, pushing the switch that Zakariassen had forgotten in his eagerness to leave.

The professor mumbled something under his breath as he leant forward to get a better view through the window. Sabvabaa was gliding smoothly forward now, the tall wall of ice sheltering it from the northerly wind.

Anna swallowed her growing nausea and saw that the blue dot on the satellite map had moved up next to the red.

The position was 89 degrees, 37 minutes, 3 seconds north, 37 degrees, 13 minutes, 10 seconds east. Not far from the pole itself.

“We should be there by now.”

She tried peering through the sleet that was settling on the windows faster than the wipers could clear it. In the glare of the powerful searchlight on the roof, the massive pressure ridge cast long shadows across the ice field. After a while, she caught sight of something blinking in the darkness.

“Stop!” she yelled. Zakariassen yanked back the throttle. The hovercraft stopped dead. He peered out.

“I can’t see anything.”

Her hand groped for the switch to the searchlights, shutting them off. It was a trick her father had taught her when she got her first car, an old Volvo that the mechanic had repaired and repainted. “Turn off the headlights for a second before each corner, then you’ll see if there are any cars coming in the other direction,” he said, before waving her a worried goodbye as she 35headed to a concert along the pitch-black, rain-sodden back roads of the Troms valley.

Once her eyes had adjusted to the dark, she spotted them. Sparkling lights on the other side of the pressure ridge wall. They had to be the lights from the Chinese base.

Zakariassen saw them at the same time, and re-engaged the power. The lights from Ice Dragon streamed in through the snowed-up windscreen. They were powerful and floated high above ground, like UFOs. On Anna’s display, the green and red dots merged.

An alarm sounded.

The anti-collision warning flashed on the radar screen. The teeth of a beast appeared right ahead of them. Zakariassen swerved abruptly to the left. The hovercraft lunged wildly, avoiding the nearest monster tooth. In the bright light, she saw that they were oil barrels lying in the snow.

Behind the barrels a cabin came into view, painted blue.

Zakariassen steered past the cabin and set the propeller in reverse so that they came to a stop under the UFO lights. Anna didn’t notice that she had been holding her breath until black dots began fizzing at the edge of her field of vision.

Her eyes stung as she looked up at the glare above them. Compared to the dark polar night they had just driven through, this was like arriving in a neon heaven.

7

When the engine stopped, Sabvabaa became strangely still. Outside, Anna saw the snow swirling in tight swarms through the bright floodlights illuminating the Chinese base. Even though the engine was stopped, the windows still rattled. One of the instruments indicated that the storm that Boris had warned about was on its way. She was looking for an excuse to do nothing, just to sit there in her warm seat, close her eyes, and fade into oblivion. “It’s blowing almost fifty kilometres an hour already,” she said. “Almost a gale.”

“Yes, yes, you think I don’t know that already?” Zakariassen looked at her irritably. “We knew what we were getting into.” He increased the speed of the wipers to get a better look. Their rubber strips, frozen stiff, screeched offensively at her as they wheeled over the film of ice that had formed on the windscreen.

The deluge of light they were trapped under was pouring down from the top of a tower that thrust up behind a large yellow building. It was at least seven metres tall and around fifty metres wide. More like an industrial warehouse.

Surrounding the yellow building were smaller, red polar cabins in a horseshoe formation. Light came from most windows, but nothing stirred and there were no curious faces to be seen inside. Zakariassen blew onto his glasses, wiping and pushing them back into place on his narrow nose, then looked at the instrument panel. His fingers fumbled for a switch.

Anna jumped at the siren blare from the hovercraft’s roof.

The wind and the snow swallowed the blast. 37

Zakariassen sounded a longer burst. Both he and Anna stared towards the floodlit base. In the red cabins, no doors opened. Nobody came running out of the dark. Apart from the wailing of the wind, the only sound that Anna could hear was a remote, rhythmic pounding. A steady beating.

Zakariassen also noticed the noise. He exhaled slowly through his nose. A worried expression. Anna realized it had just dawned on him that there was no guarantee that this particular rescue mission would end with a simple act of heroism.

“We should let the institute know,” he said finally.

The fabric of his survival suit creaked as he picked up the satellite phone receiver that he kept in a holder on the instrument panel.

“Yes, we are at the Chinese base.” He spoke loudly when the head of the institute in Bergen replied. “No, we haven’t seen anyone yet… What was that? Please repeat… I can’t hear… Yes, yes, I’ll let you know. We’ll take a look. Of course we’ll be careful.”

He switched the telephone off, stood up and walked over to the worktable, pulling open a drawer and picking up a black object. He turned around, holding it out towards her. Anna saw the holster holding the large Smith & Wesson Magnum revolver that Zakariassen had bought in Longyearbyen.

“I don’t use firearms.”

Zakariassen had looked at Anna in astonishment when he heard the words. She uttered them in the lobby of the Radisson hotel they were staying at while they were waiting for Polarstern to dock in Longyearbyen to collect them, Sabvabaa and the rest of the equipment. The hotel was full of Japanese and Americans wandering around in thick socks and oversized down jackets. A sign at the entrance made it clear that boots were not to be worn inside the hotel. Another directed that firearms—revolvers, 38pistols and rifles—were to be placed in one of the hotel’s weapons safes and that the key could be collected from reception.

Zakariassen had been out to buy the Smith & Wesson revolver from a mineworker who was returning home. On Svalbard, all inhabitants are instructed to carry a firearm when venturing outside urban areas. The day before, Anna had seen a mother on a snowmobile dropping her children at a kindergarten right in the city centre, a revolver hanging from her belt.

“You surely don’t mean that you don’t shoot? You’re a soldier, aren’t you?” said Zakariassen.

“I was a soldier.”

“But why?”

“That’s my business. I don’t use firearms.”

“No, no, there’s no discussion… We can’t be in the North Pole without weapons.”

“I have a weapon.”

Zakariassen laughed out loud when Anna showed him the Japanese sports bow she had bought in Tokyo years ago.

“You’re going to shoot a polar bear with a bow and arrow?”

“I’d rather not. I think I’ll manage to scare them off by growling and waving my arms.”

In the end, Zakariassen had reluctantly accepted that Anna would use neither his old Mauser rifle nor the revolver—especially after he had seen her use the bow. The targets were empty tin cans she had placed on top of a large block of ice next to Sabvabaa. Quickly and effectively, and at a distance of twenty metres, she dispatched every single one of them. As the bowstring launched its arrow, an echo bounced back from the surrounding ice like a sharp whip-crack. When the professor picked up one of the targets, the arrow had penetrated straight through the tin that had contained the lapskaus stew they had eaten for dinner the day before.

*

39Zakariassen pressed the leather holster holding the revolver into Anna’s hand and pointed to the snow whirling past in the bright light outside. “We cannot walk out into a full storm in zero visibility without protecting ourselves against polar bears… You won’t be able to shoot a bow and arrow now… You of all damn people understand that, surely.”

Anna sensed her own physical disgust as the revolver’s metal brushed her hand. She tightened her fist.

“No, I can’t.”

“You can’t shoot a bow in these conditions,” he protested.

She got up out of her seat and walked to her bed at the back of the cabin, pulling out the ragged North Face bag that was stored underneath it. She unzipped it and hunted her way through underwear, socks, T-shirts, long johns and books she had never got round to starting. Under an unopened bottle of Lagavulin single malt whisky, she finally found a leather sheath. She opened it up and pulled out the knife it was shielding, a long, matt-black blade terminating in a solid leather handle. A hunting knife she had won in an arm-wrestling contest against an American marine in Bosnia. The soldier hadn’t realized that he was facing a three-time Scandinavian youth arm-wrestling champion. Her technique beat his strength with ease; it took two seconds for the loudmouth to cave in once she forced his arm down.

“I am armed, see?” Anna opened the side pocket of her survival suit, slipping the knife into it as Zakariassen looked on in frustration. He grunted something and picked up the cartridge clip he always placed on the windowsill after being out on the ice with his old Mauser rifle. It clicked damply as he pushed it in. He ran the moisture out of his hair with his hand and looked back at Anna firmly.

“Now we had better get out there and find out what the Chinese are playing at.”