6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

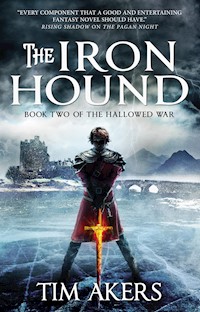

MAD GODS WALK THE LAND Tensions flare between north and south, and hatreds erupt into war. Yet the conflicts of men are quickly overshadowed by a far greater threat. Creatures long kept confined rise from below, spreading destruction on an unimaginable scale. The flames of war are fanned by the Celestial Church, whose inquisitors and holy knights seek to destroy the pagans wherever they are found. A secret cabal creates unexpected allies, and pursues its own dark agenda... While Malcolm Blakley seeks to end the war before all of Tenumbra is consumed, his son Ian searches for the huntress Gwendolyn Adair, and finds himself shadowed by the totem of his family, the Iron Hound. Gwen herself becomes allied with the pagans, and wrestles with the effect of having been bound to a god.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from Tim Akers and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1 Lost Causes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

2 Mad Gods

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

3 Demon Nights

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Coming Soon from Titan Books

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TIM AKERS AND TITAN BOOKS

The Pagan Night

The Winter Vow (August 2018)

THE IRON HOUND Print edition ISBN: 9781783299508 Electronic edition ISBN: 9781783299515

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: August 2017 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2017 Tim Akers. All rights reserved.

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

This book is dedicated to the readers who have followed me from the earliest days of Veridon, into the city of Ash, and finally onto the mad and rolling hills of Tenumbra. Here’s to a thousand adventures, and a thousand more.

1

LOST CAUSES

1

THEY FELL LIKE a pair of suns, black and amber. Their tails curled with smoke and the burning cinders of autumn leaves. Their fall tore a wound in the sky, and in the world itself. The impact shivered the trees with a wall of air that thundered down the valley, whipping branches and stone and earth.

The river that bounded the witches’ hallow hissed with steam and frost, and the stones that formed a dozen henges scattered throughout the forest rang like bells beneath the hammer. Where they struck, their landing left a deep gash in the ground.

Gwen Adair climbed out of the trench.

Her hair was a wild mass of orange light, with sparks of red and black shimmering throughout, and her skin flickered gold and amber. She dragged a black mass behind her. Its talons dug at the earth, scraping wounds in the grass that bled shadow. The creature screeched in frustration. Gwen turned and gave it a solid kick.

“Shut up,” she hissed. “You’ve caused enough trouble. Just shut up for a moment so I can think!”

The gheist responded with a growl. “I am not your tame dog, mortal. I am the grave, the sunset, winter’s fury and summer’s fear! All mortal life ends in my embrace, just as day ends in night! I will never…”

“Shut! Up!” Gwen howled. She bent her will toward the gheist, summoning the power of the Fen god coursing through her blood to send a wave of glittering light into the mass of shadows at her heel. The gheist shivered in pain, squealing as sparks of glowing energy danced through its bones. Gwen withdrew the lash, and the demon’s cries subsided. It settled down, collapsing into a slowly swirling darkness, the bright tips of its claws clicking quietly together. An eye, slate gray and endless, blinked open.

“You can not hold us forever, iron girl,” it whispered. Its voice was like a whetstone, sharpening the air. “Already I feel you dying. Whatever you have become, whatever understanding you have with Fomharra, I will be free once again.”

“We’ll see,” Gwen muttered. The name was unfamiliar to her, though the spirit in her bones thrilled at the word. She gave the gheist another kick and started dragging it forward once again. The broken hill at the center of the hallow loomed in front of her, its peak a ruin of stone and torn sod. Her feet dug into the grass as she pulled the gheist uphill.

There was something else holding her back. The god bound in her heart recognized this place, and did not want to return. She didn’t blame it. The witches’ hallow had served as its prison—or sanctuary, or tomb—for generations. Silent centuries spent in darkness. She could feel its isolation in her blood.

Gwen reached the crevasse that led into the hill, and paused. Sunlight drifted peacefully into the tomb. The body of one of the inquisitors lay halfway down, his skin dry and leathery, his life consumed by the power of the god’s awakening. There was no sign of the others. From her perch, Gwen was able to see the distant shimmering of the river, and the blooming fields of flowers that marked the final resting spot of the hallow’s guardians.

Something moved among the trees, a herd of creatures very much like deer, only made of wicker and stone. They pranced nervously among the shadows. The scattered henges, once used to focus the wards that protected this place, lay abandoned.

The hallow was a ruin, its power fled. Hopefully there was enough of its ancient force left to perform one final task.

She started down into the tomb. The death gheist gave one last mighty struggle, wings flapping and talons scrabbling at the stone, its voice silent in the effort. Gwen dragged it under, and as soon as they landed among the scattered stones of the Fen god’s cairn, the death gheist collapsed into silence. Gwen dusted her hands—purely a habit, as her sun-bright skin seemed impervious to dirt—and looked around.

A lot had changed, and yet nothing. Here the Fen god was once buried. Here the pillar that held its spirit, cracked like an egg, Gwen’s bloodwrought dagger still embedded in its heart. The smooth stones of the cairn lay tumbled around the sanctuary. The air smelled like dry leaves and wet roots. The crystals that had illuminated the tomb flickered dimly in the sunlight.

“So this is your plan,” the gheist whispered as she released her grip. “Bury me as they buried Fomharra. Hide me away from mortal eyes, that my power might be contained.” The demon curled in the dark corner, eyes and claws glinting in the bare light. “It did not work before. It will not work now. Especially with your house fallen.”

“I’m not a fool,” Gwen said. “The witches’ hallow was only able to shelter the Fen god because of the wardens. Now the wardens are all dead.”

“You could replace them,” the gheist said. “You could become my true guardian, and stand eternal watch at my tomb. Your family served that role. You could assume it, become the true guardian of the pagan watch.”

“Given eternity, I’m sure you’d find some way to trick your way to freedom,” Gwen answered. “Hells, given eternity, I might let you go just to get some peace from your damned whispering. No, that would never do.”

“Then what? Will you raise an army of pagans to hold me here? Negotiate with Heartsbridge to imprison me? Surely the inquisition can’t be trusted again?” The gheist slithered away, the coiled strands of shadow that formed its body tightening into a fist. “Face it, huntress. You have no plan, and no hope. Release me, and spare yourself the corruption I will bring.”

“I don’t have a plan… yet,” she allowed, strolling to the cairn and starting to arrange the stones. “But I figure there’s enough power here to hold you for a while, and in the meantime I can come up with something. Or someone will. You really—”

The gheist struck her from behind. A swirling cloud of shadow-tipped claws spun out of the boiling mass of its form, clattering off the stones before cutting into Gwen’s back. Black wounds appeared across her body. She fell forward, skinning her hands so that they bled on the stones.

“You are as soft as all the children of blood,” the gheist hissed. It rose, its snapping tendrils looming against the hollow shell of the hill. “So wise. So clever. So bright… but you all die, eventually. You all come to me, no matter how fast you run.”

“You will find more than blood in my veins,” Gwen answered. She pushed herself up, her hands slipping on the blood-slick rock. She turned slowly, drawing the autumn gheist around her like a cloak. Her eyes turned to gold, and a mantle of sun-bright leaves settled across her shoulders, turning her skin the color of beaten copper. The dark wounds filled with glowing light. The darkness leached away, spattering to the floor like burning pitch.

“I will let others run,” she said. “I mean to stand against you.”

“Stand and fall. Run and fall,” the gheist said, slate gray eyes narrowing into slits. “It matters not.”

They crashed together. The impact sent sparks flying through the empty tomb, sizzling out in the damp earth, leaving only the flashing light of their struggle to illuminate the damp air. The gheist struck, fell back, struck again, each attack a sweep of talons that appeared out of its shadowed body and then disappeared just as quickly. Each time Gwen turned to face the demon, its form melted into the surrounding shadows, only to reappear somewhere else in the damp confines of the tomb. Every time she blocked its attack, a small fragment of her divine light dissipated.

Suddenly the assault ended, leaving a musty silence.

“You will not escape, demon,” Gwen panted. She turned slowly in the center of the room, gathering her strength and her courage. “I won’t let you.”

“Let me?” The gheist’s voice slithered in from the shadows. “As if you have the strength to oppose the god of death!”

“Sacombre held you. A mortal man, and without ancient rites.” Gwen drew herself up. The mantle of the autumn god glistened around her shoulders, shining brighter, filling the tomb with light. The dark gheist crouched in the corner. “If that fool can contain you, surely the huntress of Adair, holding the power of the god of autumn, can do no less.”

“I was invited by the gray priest, not compelled, and when he was used up, I discarded him,” the gheist replied. “For all your piety, you are no shaman. The autumn god is not yours to command, any more than the ocean bows to the will of the ship, or the storm to the fluttering leaf!”

“Test my strength, and you will see your error, demon!” Gwen shouted, her voice echoing off the walls. She reached out to the autumn god, drawing light into a bright spear of power that materialized in her hands. Something stirred beneath her soul, beyond the ken of her mind. She pushed it back, and howled her fury. “I will bind you, or destroy you, or both!”

“She flinches from your touch, child,” the gheist said. The pool of shadows that formed its body spread thin, leaking out into the cracked walls of the tomb. “Your tame god will burn her leash, and taste the blood of her master.”

“Do not think to flee!” Gwen shouted. She whirled around, trying to keep her attention in every corner of the damp room, burning still brighter to illuminate the lurking darkness. “Do not make me hunt you.”

“I have never been prey,” the gheist whispered. A column of barbed shadow launched out from the darkness, crashing into Gwen’s bright shield. She resisted for a moment, then the gheist’s oil-black body lapped around her defenses, cutting deep.

With a sudden impact the demon threw her through the crumbling shell of the hill, punching her body through stone and sod until she flew free of the tomb. Gwen rolled as limp as a rag through the rough grass of the hallow, coming to rest among the poisoned flowers where Frair Lucas had nearly died. She lay there, the autumn god swirling around her. The spirit that was pinned to her soul thrashed like a fish on the line.

The death god blossomed from the hill, rising into the sky on shadow-torn wings. It swept down the hill to where Gwen lay, settling on the edge of the clearing and grinning with its legion of teeth.

“It will not need you much longer,” the gheist murmured, cocking its head curiously. “Your precious god will discard you, as I discarded that fool Sacombre. Give in to it. Surrender. Why would you hold a god you don’t understand?”

“Not understanding is part of it,” Gwen muttered. “I have Elsa to thank for that.” She struggled to her feet. The bright red petals of the poisoned flowers burst at her touch.

The autumn god fought to get free. She could feel it pulling at her deepest flesh, at the tattered shards of her soul. Nevertheless, Gwen faced off against the swirling darkness at the edge of the field, wondering if it had been a mistake, bringing death to this place. Maybe it would be her last mistake.

“Poor, foolish child,” the gheist hissed. It grew over the clearing, its thin limbs weaving together into a canopy of night. “You were not this god’s chosen avatar. It must have been an act of true desperation, for the witches to sacrifice one so dreadfully unprepared. Have they fallen so far?”

“You talk too much,” Gwen snapped.

“I’ve been caged far too long, and that priest had nothing interesting to say. All damnation and vengeance and war.” The gheist continued to uncoil, reaching dark arms around the clearing, occulting the forest and cutting Gwen off from the rest of the hallow. “There is plenty to enjoy, certainly, but butchery is bland. Tasteless.” It crept closer, black tendrils drifting into the clearing like drops of ink in water. “Nothing as exquisite as the cultivated murder.”

“It’s clear why you and Sacombre got along so well,” she responded, “and surprising that you left him behind.”

“Death is not meant to be leashed, child,” the gheist answered. “Sacombre should have known that, but you mortals, always dancing away from the darkness, thinking you can cheat the final tally. Summer always becomes winter. Birth is only the first step toward death.”

“As winter becomes spring,” Gwen hissed. “You seem to forget that, demon.”

“Demon? You should name me god, not demon.” The gheist swelled to its full height, glaring down at Gwen. “Have you abandoned the faith of your house so quickly? Has the death of your family shaken your beliefs?”

“Death of my…” Gwen shrank away. “What are you talking about?”

“Oh, yes. Yes, of course. You suspected, didn’t you, but that is different from knowing. Here,” the gheist whispered, withdrawing a little, drawing a spindly arm back as though pulling aside a curtain. The air split, and shadows filled the sky. “I brought them with me, so that you might say good-bye.”

A door opened in the shadows, and through it walked Gwen’s father. He was fractured, like a statue roughly hacked apart and then haphazardly rebuilt. Colm Adair’s face was bloodless, the wounds that crossed his body puckered and raw, the skin peeling back like a toothless smile. When he saw his daughter, Colm tried to speak, but no words left his mouth. Only a painful, grating sound.

“What have you done to him?” Gwen demanded. Something began to break inside of her, a pain as real and cold as a knife wound. She took a step forward. “What have you done to my father?”

“What have I done?” the gheist echoed. “Nothing. This is Sacombre’s work… and yours, as well.” It waved another sinuous arm, and two more figures appeared in the shadows. “Your mother and brother fared no better, I am afraid, though their deaths were quicker. Lady Elspeth barely had time to scream, I think.”

Elspeth and Grieg looked much as they had the last time Gwen had seen them, except for scarves of crimson blood that spilled from their throats and onto their breasts, the wounds in their necks still weeping. Young Grieg looked startled, but there was only fear in Elspeth’s eyes.

“The silence is the worst part,” the gheist said, motioning to Elspeth’s flopping lips, the only sound a wet gurgle that bubbled from her severed throat. “Hardly fair. But I can remedy that, and give them voice. Here.”

The gheist floated behind them, the inky tendrils of its body caressing Lady Elspeth’s pale corpse. A shadow passed through her skin and stitched shut the wound in her neck. Gwen’s mother twisted around and took a startled breath, blood dribbling from her lips. Then she turned to Gwen and raised her hands.

“I could do nothing,” she said. “Nothing! Sacombre stepped from the shadows and snatched my son up like… like… as if to hug him. He turned my boy toward me and ran a blade across his throat.” Elspeth’s eyes turned wet, tears spilling down her cheeks. She bent to Grieg, who stood swaying in the field, staring up at Gwen. Elspeth ran lily-white fingers over the sticky wound in her son’s throat, as though she could close it with her touch. Her fingers trembled. “He killed my boy. He killed my son.”

“Stop it,” Gwen hissed. Her voice failed her, and she realized tears were streaming down her face. She backed away from the phantoms of her dead family. “Stop doing this. You’re mocking them. You’re mocking me.”

“I am showing you what you face,” the gheist answered. It rose up, sliding to the side of the three dead bodies. The wound in Elspeth’s neck reopened, and her breath disappeared in a bubbling torrent of sobs. “They are mine now. Their bodies, their lives. Every memory you have of them, every happy moment you spent in their company, every hope you had for their future. Mine. Dead. Buried. In the grave. Mine is a blade that will never stop cutting, and from which no one can escape.

“Not even you.”

“You’re a terrible god,” Gwen muttered through her tears. “A god of misery. I will never serve you.”

“No, but you will bow to me.” The gheist drifted closer, its slate eyes narrowed, the wicked whisper of its claws dragging through the grass. “Everyone does. I am nothing like that tame bitch you’re riding.”

Something stirred in Gwen’s bones, a torch of rage that whispered up from her soul. The autumn gheist moved around her shoulders, quiet and angry. Gwen struggled for a breath, but then the god that was stitched to her bones broke through her skin, seizing control and speaking through her, its anger humming through her bones.

“You have had your fun, Eldoreath,” a voice said, ringing with golden bells and fury. “The mortal child is broken, and my season is passing—but before I go, I will show you tame.” The words were not Gwen’s, their meaning risen from a soul that had never known flesh. “The conclave was right to bury your madness. Now I must finish their job.”

“Which of us is truly risen, child?” the death gheist asked. “And which of us slept her way through the wars?”

“Mad dogs don’t rise. They merely slip the leash for a while. Now put away your toys, and face the rage of an endless god!”

Like puppets whose strings had been cut, the dead of House Adair fell to the ground. Colm Adair came apart like a puzzle that has been dropped. Grieg and Elspeth fell together, their arms folding over each other in a final embrace, mother comforting son, son seeking the sanctuary of his mother’s love. It broke Gwen to watch, but she could do nothing.

The autumn gheist filled the clearing with sunset light. The poison flowers wilted, their petals breaking into new growths that squirmed between the grasses like snakes.

Eldoreath burst forth, squeezing the clearing with the domed darkness of its limbs, trying to crush Gwen and Fomharra in a web of night. Like a coal smothered in ashes, Gwen burned hotter and hotter, brighter and brighter, until the flames of the autumn gheist slowly started breaking through the death god’s trap. The tangled web of its attack started to give. One night-dark strand snapped, and then a second, and then Gwen rose, and the god through her.

She rose into the sky on a spear of light, a pillar of golden leaves that shuffled over her flesh like velvet. At the base, the death gheist lay in a heap, like a rubble of broken trees. Slowly, it patched itself together, gathering the shattered bits of its body together.

Fomharra laughed, and the sound shook the forest.

“Nothing clever left to say? No more promises of death, or exquisite murder?” Gwen looked down at the death god and laughed again. “Well, I’m glad to have shut you up, once and for—”

Gwen started to fall.

2

THE DIM LIGHT of dozens of campfires stretched to the horizon, their flames flickering beneath the banners of the south. Tents creaked in the stiff autumn wind, and laughter drifted up from the Suhdrin camp. Above them, the sky was crowned in glittering stars, and Cinder’s pale face hung like a coin in the sky.

A second camp clustered inside of the Fen Gate’s ruined walls. The Tenerrans were a somber lot, staying close to the castle walls and talking quietly among themselves. The guards that roamed the perimeter were deadly serious, as scared of the Suhdrin army as they were of the coiled shadows of the forest. The season of mad gods was at hand, and only a fool would walk the night alone, especially in a castle as haunted as the Fen Gate was purported to be.

The center of the castle was mostly ruin. The famous towers of Adair’s keep lay in shambles, the shattered doma and attendant halls haphazardly repaired. The only buildings that were untouched by the Fen god’s assault were the stables, the kennel, and the lonely splinter of the huntress’ tower.

“Will they ever go home?” Malcolm muttered. He stood on what remained of the Fen Gate’s battlement, cloak clutched tightly to his chin, the chill of the coming winter sharp in his bones. Castian Jaerdin stood beside him, along with a handful of guards. Jaerdin stomped his feet against the wall, trying to hammer some warmth into his toes. The duke of Redgarden sighed.

“They have no taste for winter. A good frost will drive them back to the Burning Coast,” Jaerdin said.

“Somehow I think their spirit will not be so easily broken,” Malcolm answered.

“Half their number has already retreated to Suhdra. The rest will follow, in time—and gods bless it’s soon, so that I may join them and leave this miserable land,” Jaerdin said unhappily. Malcolm chuckled. His friend was bound temple to toe in fur and misery.

“You are welcome to return home, Redgarden,” Malcolm said. “Roard has joined his banner to our cause, and Sacombre’s heresy has taken the fire from the Suhdrin host. This war is all but over.”

Jaerdin grunted. He nodded toward the two opposing camps and the slow orbit of guards.

“This does not look like a field of peace,” he said.

“No,” Malcolm said. “It does not.”

“We must be careful, Malcolm. This was a short fight, a short season of war. These armies are merely what Halverdt was able to draw to his cause in a few months, bolstered by Sacombre’s support.” Jaerdin paused for a moment, weighing his words. “There are many spears in the south, many that have not yet stirred. We must play our cards carefully to keep them there. It is good that Roard stands with us, but not enough.”

“You worry about Suhdra,” Malcolm said. “I get messages from the north every day, promising support should Halverdt’s host push further in their direction. Promising spears and horses and the full fury of Tener. We were lucky to keep them out of the fight so far. If Suhdra escalates, we will not be so fortunate.” He gestured down to the camps clustered below. “The smart ones have gone home. Only the stubborn remain.”

“The stubborn and the zealous,” Castian answered. “Those who travel south carry stories of Adair’s heresy, along with the bodies of their dead. Their families will mourn, and then perhaps they will march. To avenge those deaths.”

“May aye. May nay,” Malcolm said. “Gods will know soon enough.”

Jaerdin didn’t answer. He just stood there, beating his feet against the stone and muttering. A messenger picked his way up the tumbling stairs to approach the two dukes. One of the guards intercepted the man, checking his identity and searching for weapons among the bundled bulk of his cloak and armor. Castian and Malcolm watched.

“This weather really is foul,” Castian muttered. “I don’t know how you stand it.”

“There is a reason we invented whiskey, Redgarden. It keeps winter at bay.”

“Last time I was at the doma, the frair sang the autumn bell,” Castian answered. “We are barely out of summer, Houndhallow.”

“Winter has come early,” Malcolm agreed with a nod, “and sharp.”

“My scouts say that a dozen leagues to our south the weather breaks. Gentle autumn still reigns in most of Tenumbra, Malcolm. It’s only our little ruin that suffers,” Castian said, hopping lightly from foot to foot. “If there was any doubt this place was cursed before…”

“Enough of that talk,” Malcolm said sharply. “My men already jump at every shadow and mouse. No need for them to hear their lords discussing curses.” He raised his voice to the guards. “Let the man through, Aine. If he has a hidden blade under all those layers, it will take the better part of the night for him to draw it.”

The guard grudgingly obeyed, but kept a close eye on the messenger. Malcolm saw why the man mistrusted the newcomer—he was dressed in the black and gold of the church.

“News from Heartsbridge?” Malcolm asked.

“Aye, my lord,” the man said. “His holiness Gaston LeBrieure, celestriarch of the Cinder and Strife, sends his greetings and deepest thanks for your role in uncovering the heresy of the high inquisitor.”

“And the heresy of dear Colm Adair, I imagine,” Malcolm muttered. “Gods know what they’ll make of that in Heartsbridge.”

“Such matters will be left in the inquisitor’s hands, I am sure,” the messenger said with a bow.

“Inquisitor?” Malcolm asked. “Listen, the celestriarch may be a little behind in the proceedings, but Frair Lucas left us some weeks ago. There’s no other representative of the inquisition at the Fen Gate.”

“Precisely,” the man said. “Which is why a new inquisitor will be here shortly. I left his company a day ago to give you fair warning, that his chambers might be prepared.”

“A day ago?” Malcolm asked.

“Yes,” the messenger answered. “He should be here—”

“In the morning,” Jaerdin finished.

“Well,” Malcolm said stiffly. He turned to Castian and nodded his farewell. “I have preparations to make, I suppose. Aine, see that this man is given something to eat and a blanket to sleep on.”

“My lord,” the guard said.

“Where will we put them?” Castian asked. “It’s not like the keep’s fit for habitation. It wouldn’t do to have the roof fall on their heads while they pray. Gods know what the church would make of that.”

“No, and I’m not sure I want to put him in Gwendolyn’s tower,” Malcolm answered. “Not until we know the depth and craft of her heresy. It could be dangerous.”

“Dangerous?” Castian said. “I sleep in the huntress’s tower, Malcolm!”

“And you’re a braver man for it,” Malcolm answered with a smile. “But no, we can’t have them in the keep nor in the tower, and there’s no more room in the courtyard—even if the frair was willing to take a tent. I must think of something.”

“Perhaps the Suhdrins could serve host to the inquisitor,” the messenger said sharply. “If you can’t find a bed worthy of the celestriarch’s chosen envoy…”

“The inquisitor did not come all this way to sleep outside the walls,” Castian said. “Last I checked, the Suhdrin host was out there, and we are in here.”

“And they haven’t the numbers to shift us,” Malcolm said. “That much we’ve proven.”

“Not yet,” the messenger said. Malcolm and Castian grew still, staring at the man. “They haven’t the numbers to shift you yet.” He glanced up from his stiff bow to crack a smile. “How many would it take, do you think?”

“What have you seen?” Castian snapped. “You traveled here from Heartsbridge. What did you pass along the way?”

“Again, I will leave that for the inquisitor.” He turned to the guard. “There was talk of a bed? It has been a long day.”

Malcolm kept his eyes on the messenger. After a moment he nodded stiffly to the guard, watching as the man was led away. When they were alone on the parapet, he turned to Castian.

“What was that about?” he asked.

“A threat? A warning?” Castian ventured. “Perhaps the inquisition will stir up trouble as they come north. I would not put it past them. They won’t want the Circle of Lords to focus on Sacombre, not for too long. Better that the dukes worry about the threat of Tener.”

“The threat of Tener,” Malcolm said. “The threat of the pagan night.”

“Whether real or not,” Castian agreed. “Best we find the inquisitor a comfortable bed.”

“I’d hoped to have the doma repaired before anyone from Heartsbridge arrived,” Malcolm said with a sigh. “I wanted them to find us faithful. Singing the evensong. Observing the rites.”

“They know of your faith, Malcolm,” Castian said.

“Do they? Perhaps.” Malcolm stirred himself and started toward the stairs. “I leave you to this miserable view, Redgarden. If there is a Suhdrin army marching north, I must speak with my fellow lords before news of it reaches the camps.”

“Good night, Houndhallow,” Castian said, turning back to stare uncomfortably over the vista. “And godspeed.”

Malcolm hurried down the stairs, nearly tripping on the broken stones of the stairwell. Morning didn’t give him much time. And there was much to do.

Grant MaeHerron was waiting at the base of the wall. The big man was dressed for battle, his axe cradled loosely in his arms like a child. The heir of the Feltower—still presumptive until his father’s death could be confirmed—was never far from his axe. The edge shone as bright as silver in the torchlight.

Malcolm nodded. “We have guests coming, Feltower.”

“Sir MaeHerron, if you please,” the man rumbled. “My father may live.”

“You must accept his passing, Grant,” Malcolm said quietly. He had known the boy since his birth. Grant MaeHerron was a few years older than his own son, and had always kept himself apart from the rest of the children of the Tenerran court, but it was hard to think of him as the duke of the Feltower. “You must accept your father’s death, and his title. Your men need you. We all need you.”

“He may live,” Grant repeated stubbornly, hugging the weapon closer.

Malcolm sighed, but shook his head. “We will discuss this another day. For now, there is news from the south, and preparations to be made.”

“I saw the church’s messenger when he arrived,” Grant said. “His horse was near dead. The inquisition is coming?”

“They’ll be here in the morning,” Malcolm said, “but that is not our greatest worry. Are the other lords awake?”

“Roard and his whelp watch the gate. Dougal and Thaen take some rest. Jaerdin was with you. I don’t know where the others are.”

“Gather them. The Tenerrans only. Leave Roard at his watch,” Malcolm said. “What of Rudaine’s host? Who commands the men of the Drowned Hall?”

“His master of guard, a man named Franklin Gast. Word has been sent, to ascertain the will of Rudaine’s heir,” Grant said. “They may leave us.”

“Go wake them, and bring them to what remains of the doma. We have much to discuss.”

“Are we finally breaching the subject of surrender?” Grant asked.

“Wait for the doma,” Malcolm said. “We will have a friar bless the meeting, and then we will see what is necessary.”

Grant MaeHerron nodded gruffly, then left, still clutching his axe. That man would not surrender easily, Malcolm knew, either his hope or this castle. He turned and slipped into the shadows of the ruined keep.

Hurrying through the corridors, he nodded imperceptibly to each of the dozen hidden guards who protected this part of the castle from curious eyes. They were dressed as stablers, cooks, pages shirking their duties in the abandoned halls of the castle, but each wore chain under their disguise and kept sword and spear near to hand. They let Malcolm pass without comment.

He came to a door and knocked. There were muffled voices inside.

“Who goes?”

“Her husband,” Malcolm answered, careful to not use his name or station. Anyone trying to impersonate him would surely draw on the duke’s authority to bull his or her way inside. “Let me in, Doone.”

He heard someone pull aside the cloth that was jammed beneath the door, a dim light filling the corridor as soon as it was clear. Locks were thrown. Sir Doone eased the door open, her eyes flicking past Malcolm to the corridor beyond. Once she was sure things were safe, she urged Malcolm inside and closed the door. The locks were in place before Malcolm’s eyes had adjusted to the gloom.

His wife provided the only light in the room. The witch’s touch that had saved her life and cursed her flesh had changed Sorcha into a creature of strange light and stranger mien. She sat in a chair of fitted stone, its surface weeping with condensation. There were no windows in the narrow chamber, but Lady Blakley still stared wistfully to the west, the direction her son had traveled weeks ago. Her veins glowed with murky light.

Sorcha’s blood was gone, transformed into clear, bright liquid that flickered with an inner light. When she glanced at Malcolm, her eyes were deep pools of shimmering water, and her hair shifted restlessly around her head like a crown of seaweed. Malcolm went to one knee beside her.

“My love?” he whispered. “We must go.”

3

GWEN FELL AND didn’t stop. Whatever strange link held her in the pillar of light was coming loose. Panic welling up, she could feel her soul snagging on some unseen line as she tumbled through the leaves, struck the ground with a thump, bounced, crashed down again. Her breath left her, and her skull rang like a bell.

As she lay there senseless for a moment, her vision swam with the forest and the sky and the towering body of the autumn gheist. Gwen tried to stand, but the strength was gone from her limbs. She tried to cry out, but could only gape like a beached fish. Her breath began to come back to her, when an unspeakable force grabbed her and dragged her along the forest floor.

Gwen bounced from tree to mossy stone, digging a rut in the damp sod whenever she thumped back to earth. She lurched, jerking along for a dozen yards and then stopping. Pulled forward again, going through bracklebush and grassy field. Finally, between crashing jerks, she was able to reach her feet and look around.

The autumn gheist had been dragging her like a forgotten toy. A fragile net of amber light trailed from the god’s body, tangling among Gwen’s limbs, disappearing into her flesh and emerging again. Before she could say or do anything, the gheist took another massive step, jerking her off her feet and crashing through the forest.

Fomharra stopped again, and Gwen was able to quickly regain her feet.

“Wait!” she shouted. “Where are you going? Come back!”

“You do not hold me, child,” the gheist breathed, its voice humming through Gwen’s skull. “And my season is done.”

“But I need, we must… the demon!”

“We must nothing,” Fomharra said, then turned away and continued its journey. Gwen fell, tumbled, and was dragged through a field of raw stone before coming to rest on the pebbled beach of the river that bounded the hallow. From her knees, Gwen could see the bluffs beyond. She was about to cry out when the gheist moved again.

Gwen tumbled into the river.

The cold took her breath and her sense. She fought against the current, but no matter which way she thrashed, she was dragged deeper under the surface. Her lungs burned, already empty from screaming and the constant, thudding impacts of her journey. The strands of light that tied her to the towering gheist pulled her forward. By the time she reached the far shore, Gwen was limp as a rag.

River water poured clear and cold from her mouth as she was pulled up the beach. The sky and stones rolled over her. Her mind drifted. She would be shattered against the stone cliffs, or dragged into a lake, or left to freeze somewhere in the wilds of the Fen. She was dead. She was ruined.

Gwen tumbled against something stuck into the stones of the beach. It was warm to the touch, and when she folded over it, it cut her like a knife.

Like a sword.

Gwen opened her eyes.

Sir LaFey’s lost blade stuck like a mast from the ground. When the gheist moved forward, the skeins of light that bound it to Gwen strained against the blade. She thought she might be cut in half, and blood poured dark and hot from her wounds, but she stayed put. She wrapped her hands around the hilt and pulled her belly away from the cutting edge. The gheist tugged again. The lines pulled taut, humming with the strain. And then they snapped.

As she collapsed to the beach, Gwen’s blood mixed with water that was still streaming from her nostrils. She whimpered as the injuries crashed through her mind, lay there as the amber light of the autumn god dimmed on the horizon, and then was gone. Her hands had been cut deeply by the blade, and the wounds inflicted by the death gheist festered with wicked shadows.

* * *

The first footfall was nearly silent, the practiced stride of a woodland hunter, taught by the wolf and the whisper. A shadow lurked among the trees, bright eyes staring at the fallen huntress. It was joined by another shadow, and then a third, and then the forest was full of silent spears.

Cahl stepped from among the trees, followed by a cadre of pagans with their cloaks and spears and crowns of willow. He walked to Gwen and knelt beside her broken body. He glanced at the sword, Gwen’s blood leaking into the runes of Strife, remnants of heat curling off the blade.

“It is the huntress,” he said finally. He gathered her into his arms and stood. Her arms hung limp, trailing ribbons of blood. “There is still time for her soul, if not her flesh.”

“She has lost the god,” one of his companions said sharply. It was a man tattooed with a mask of leaves. “Fianna said she would fail us. What good is she to us now?”

“You have lost too much of yourself, Aedan. She is not a forest to be burned for our warmth.” Cahl stretched his cloak to cover Gwen’s unconscious body, then nodded to his other companion. The young boy, little more than a child, stepped forward eagerly. “Taeven, stay here. They will come looking for her, or for what happened to her. Warn them that the god of death has slipped its chains, and that the autumn god is lost as well.” He started to turn away, paused, glared at the sword. “And see that the vow knight gets her sword back, but be sure that she knows the cost of that blade, and the weight of the death that goes with it.”

“I will,” Taeven said seriously.

Without another word, Cahl slipped among the trees. Within moments the beach was empty of all but the young pagan, and the blade, and the sound of shadows in the forest.

4

IAN BENT HIS head close to the charger’s neck and spurred the beast on. The forest whipped past them, branches scoring bloody tracks across his cheeks. The only light was the dim image of Elsa LaFey’s fleeing form, sunlight leaking from her armor, briefly illuminating the narrow path before surrendering to the shadows. The sound of his horse, the whistling passage of trees, the hammering of his heart, all filled Ian’s head and drowned out any other thought but flight and fear.

Behind them, a mad god followed. It brushed aside the trees as though they were bowling pins, roots popping out of the soil with dull squelching sounds, trunks groaning as they fell. The earth shook.

Ian spared a glance over his shoulder. The gheist’s back writhed with a thousand barbed quills that rustled drily as they slithered together. Its head was a thick lump, mouthless, bristling with smooth black eyes. The creature was falling back, however, until only the mosaic of its eyes was visible in the scant light that shone from Elsa’s invocations. Ian smiled, turned back to the trail…

…and had to react quickly. Elsa was stopped, her mount pulled up and stomping sideways on the path. The vow knight was leaning over the saddle and looking down. Beyond her there was nothing.

Ian pulled hard on his reins. His horse complained, skidding on the damp ground as it dug iron-shod hooves into the earth. He came up just short of a ravine, its edges sharp with rocky debris. Water crashed far below.

“This way,” Elsa said quickly, then she set off along the ravine’s lip. Both directions looked the same to Ian, a jagged cliff that stretched into the darkness. He briefly considered abandoning the vow knight, counting on her holy glow to draw the gheist, but he would be lost without her. And even if he survived this attack, Ian would be helpless against the next. So he pulled his horse in line and spurred forward, trying to keep up. He glanced back again to see if their pursuer would pick up their scent.

The gheist skidded to a halt, large stones clattering over the edge of the ravine, to drop loudly into the noisy river below. It looked around, its coat of barbed quills undulating silently, and saw them. It was terribly still for a heartbeat, watching them with its multitude of eyes. Then it followed, moving faster now that it was clear of the trees.

Ian turned toward Elsa. “We should get back into the forest!” he yelled.

“Gheists have boundaries,” Elsa replied. “Even ferals have rules.”

“You think we’ll be safe across the river?”

“No idea,” she said, “but we weren’t safe in the forest, and the horses can’t keep this up much longer. We need to find a place to cross!”

She was right. Ian’s mount was quivering under his thighs. Between the constant riding and frequent pursuit, these horses didn’t have much left in them. The last thing he wanted was to have to walk out of the Fen. He had done it once, but that had been in the company of a witching wife and her shaman. There had been fewer gheists that time, too.

Fewer by far.

The barbed, bristling god came closer, and their mounts were slowing. Ian pulled up next to Elsa, the vow knight’s mount trembling at the verge of collapse. LaFey’s scarred cheeks were bright with embers. She was burning her blood to keep the horses going, but there was only so much Strife’s magic could do. The pair exchanged a look. Elsa shook her head.

“No further,” she said.

Ian looked around. This far from the forest’s edge, they were on a broad ledge of stone and moss. The horses stumbled to a halt, and Elsa slid from her saddle. She started adjusting her armor, cutting the buckles on several heavier pieces and throwing them away to clatter on the rocks.

“So, here then,” Ian said.

“Keep going,” Elsa said. Her voice was ragged. “I can hold it for a while.”

“No,” Ian answered. He slid to the ground, twisted, and cracked his back, staring down the ravine at the rapidly closing gheist. “Even if my horse could go another step, no. This is my death as much as it is yours.”

“Have a little faith,” Elsa said smartly. “I may yet live. I’m wearing armor, at least.”

“Ah, but I’m faster on my feet.”

“Just fast enough to die fancy,” she said, holding her sword at arm’s length, frowning at the blade. It was plain and gray, without the bloodwrought runes of the winter vow. Elsa had lost her sword at the witches’ hallow, when Gwen’s magical presence had swept her miles away in the blink of an eye. This blade came from the Fen Gate’s armory. “If only I had my true sword.”

“Always making excuses,” Ian said. “You don’t see me complaining.”

“No one expects much of the half-heretic son of Houndhallow,” she replied. “Once I’m gone, this forest will swallow you whole. You’re fucked, Blakley.”

And then the gheist was on them. It leapt into the air, its broad limbs going wide, claws extended, the barbed cloak of its back bristling against the night. It grew larger and larger as it jumped, its eyes twinkling brightly, and then its chest split. An ebon slash ran from throat to groin, widening as it fell toward them, until pure darkness filled the sky.

The creature’s form dissolved into the air. Its quills flaked away, becoming motes of sharp light that fluttered down like snowflakes. Its eyes scattered and became stars, twisting into unfamiliar constellations in a moonless sky. Its body dissipated into inky smoke that curled between the trees. Talons clattered to the ground.

The river was gone.

The horses were gone.

They were somewhere else.

“So,” Elsa said, still in guard position. Her sword leaked molten light, the metal of the blade popping as it fried in Elsa’s hands.

“We seem to have found a new and interesting way to die,” Ian said. He slid his blade from its scabbard. “Though I don’t remember dying. Is this the quiet?”

“I’m not the sort of priest who could tell you,” Elsa said. “Though I think not.” The ground around them turned into soft loam, sprouting with tufts of pale grass that bore a disturbing resemblance to the creature’s quills. The forest was there, but at a distance, and a thick fog swirled around them, as black as night.

“Your light is dimming,” Ian said.

“I’m tired.”

“No, I mean…” he stepped closer. “It’s as though the air is eating it.”

Elsa looked down. The cloak of sunlight that wafted off of her armor was evaporating like cobwebs touched to flame. She grunted.

“This is more than darkness,” she said. “I can see the stars just fine.”

“Yes, though they are no less disturbing,” Ian said. While they watched, the constellations disappeared in an undulating wave, to shine brighter as they reappeared.

“I’ve heard tell of gheists like this,” Elsa said. “They are a place, rather than a deity. A realm.”

“So it… ate us?”

“Absorbed, more like,” Elsa said, creeping carefully forward. “But not the horses.”

“Lucky horses.”

“May aye, may nay.” Elsa clenched her shoulders, straining against the darkness. Her sun-touched aura flared briefly and then flickered out. The vow knight staggered, and Ian reached for her. She shrugged his hand away. After a few heartbeats of silence, she shook her head, her voice rough.

“We will not be burning our way out of this.”

“Is that always your first instinct, Sir LaFey?” Ian asked gently.

“First and last and always,” she answered. “Come, there must be a way forward.”

Despite the darkness they could see where they walked, though the view bore no distinguishing landmarks. There was the distant forest, which never seemed to get closer, the barbed grass that clattered peacefully in the slight breeze, and the sky of unfamiliar stars that occasionally blinked in horizon-spanning waves.

They walked aimlessly.

“There is something among the trees,” Ian whispered.

“Yes,” Elsa answered.

He could just barely see it, out of the corner of his eye, a cloak flickering between branches, eyes the color of distant stars. A pack of predators—perhaps wolves—followed the apparition, stepping lightly through the forest like a fog.

“The god, do you think?”

“Or his demons. You’re the one steeped in pagan lore, young Houndhallow. What is this place?”

Ian kept looking around, stepping carefully among the tufts of grass, straining his ears for any hint of the river they had left behind. The trees were filled with strange sounds, like dry bones rubbing together, and the rattle of insect song.

“This is the night,” he said, finally.

“That is close enough.”

A voice came from in front of them, sounding like velvet carefully cut by the sharpest shears, as quiet and soft as a sigh. Abruptly they were at the tree line. Part of the darkness solidified, and a hunched figure stepped out. His face was smooth and dark, and his hair was pale. It was difficult to focus on his features. Ian’s gaze kept sliding away from the man’s glittering eyes, though his mouth hung in Ian’s vision like an afterimage, teeth and lips set in a grimace, the corners cracked and wet.

“Why are you crossing through my realm?”

“Crossing through?” Elsa asked. “You brought us here. We’d be happy to leave.”

“That cannot be.” The man twitched, his head shifting like a king settling his crown. A palsied hand appeared from behind the figure to briefly touch his heart. “All come to me. All are gathered to this realm. I have never sought another to bring them in. You must be mistaken.”

“And yet, here we are,” Ian said.

“Indeed,” the man said, bowing slightly at the waist. “And so I ask, what has brought you and the others to my realm?”

“The others?” Ian asked. He looked around, saw nothing but the stars and the forest and the darkness. “What others?”

“Men of steel and ink. There is a familiar taste to them, but I am a stranger to their hearts. They have forsaken me.” The man looked Ian over, lingering on his face, as though trying to recall him from some memory. “There is something of me in your heart, however. Who are you?”

“Ian Blakley, of Houndhallow,” Ian replied. “I am—”

“The hound hunts through my forests during the day, but cowers at his master’s fire when I come to him.” The man looked from Ian to Elsa, smiling as though he had made a joke. “My realm is for wolves, Ian of Hounds. Best you get going, before they find you.”

“This is worthless,” Elsa spat. She strode forward, her gait stiff, blade swept back and ready at her thigh. The loamy ground swelled beneath her feet, wrinkling into ridges that absorbed her steps. She stumbled on, but with each step her feet sunk deeper and deeper into the ground, until thick moss was churning around her waist. She shouted in frustration, and a wave of flickering light washed over the ground. The grasses crisped and turned to ash. The ground shrank away from her.

“That was hardly proper,” the strange man said. He was no longer close to them, his still form standing off to one side, fingertips lightly brushing the cracked flesh of his lips. “I know your kind, summer-child. You have your own realm. Leave me to mine.”

“Then return me, or I’ll cut my way through!”

“Hardly proper,” the man repeated, then he began to fade into the trees.

“Wait!” Ian shouted. He ran forward, and the world seemed to tilt, causing him to drop his sword. It disappeared in the darkness. He found himself running uphill, though the ground remained steady. Ian pressed on. “You can’t leave us here!”

The man looked startled at his approach, and shrank back. Ian reached the trees and used them to pull himself forward. The world tipped again, and he was suddenly hopping from trunk to trunk like the rungs of a giant’s ladder. He glanced behind, and Elsa’s light shone dimly in the fog. From this distance it looked as though she were trapped in a cage of branches, her blade flashing back and forth.

Ian struggled on.

His hand came down on something cold. Instantly a wetness spread down his arm, to drip from his elbow. His hand was wrapped around the blade of a sword, its tip buried in the trunk of a tree. He jerked back, blood trailing from his split palm, pain reaching his senses. Shaking his fingers he examined the wound, a narrow cut, not deep enough to reach muscle, but bleeding like a split wineskin.

He looked up at the tree and saw that it was a collection of arms and armor. Spears rattled against branches, broken helms hung like rusty fruit, and bodies. A half-dozen bodies dangled, their faces cloaked in mist, their limbs twisted as if in some final spasm of horror.

“The others,” Ian whispered to himself. He crept closer, careful where he placed his hands and feet, until he was alongside one of the bodies. It turned slowly on a length of chain, its limbs wasted and thin. The corpse wore the black tabard of House Thyber. The sigil of the earl of Cindermouth, the pale hand seared with a crescent moon on the palm, hung in tatters from the dead man’s chest.

Again the forest changed. It became vertical, the ground a sheer cliff from which the trees emerged like arrow shafts. They shifted and formed a thick web of stone-hard wood, their canopies lost in swirling fog, their roots pulling free of the earth until there was no ground, only the directionless maze of branches and trunks—wiry limbs that snarled together. And still Ian climbed. There was a light ahead.

It was Elsa. She hung in the middle of a tangled ball of wicker, limbs bound and skin scratched raw. A steady flame flickered from the blade of her sword, and the branches around it were charred black. Then the steel, untempered in the holy forge of the Lightfort, began to fail. On seeing Ian, she struggled to turn toward him. The trees resisted, groaning as she twisted in their grasp. Her face was clutched by whip-thin branches that burrowed into her flesh. The blood that leaked from those wounds was stained with ash.

“I have no power here,” she whispered. “I burn, and the tree falls away, but eventually it returns. And this blade will not last much longer. Where have you been?”

“Climbing,” Ian said. “I just left your side.”

“Hours ago,” she said. “Where is our friend?”

Ian looked up into the maze of tree, and then down. Fogs swirled all around.

“I don’t know,” he admitted, “but I think I found the others he was talking about. Men of Thyber, long dead. I wonder what they were doing in the Fen?”

“An interesting question for a later time,” Elsa said. Ian raised his brows.

“Do you want me to cut you free?” he asked.

“No, Ian. I want you to leave me to die,” she said tightly. “You idiot.”

Ian reached for his sword, then remembered. There was a knife in his boot, though, so he drew that and started working on the tangle of branches that held Sir LaFey in place. The wood was tough, the bark cutting his knuckles as he sawed through it, and the flesh beneath was dense and fibrous. Still he cut and cut, his own blood running down his fingers until the handle of the knife was red and slick.

The first branch snapped, and then another. He burrowed deeper into the tangle of wood, grabbing handfuls of branches and putting them to the knife. The tree creaked around him.

“Careful,” Elsa hissed. Ian glanced up with a smile.

“Don’t worry. It’s not like you’re going to fall or anything.”

“No, you idiot! The tree!”

Ian looked back down at his hands. Thin branches were cradling his wrists, and as he jerked his arms back they looped as tight as a snare, trapping him. He yelped, and started cutting at his restraints, but other branches coiled closer, hooking into his elbows, twining between his fingers, drinking the blood of his wounds.

He dropped the knife and watched as the tree pulled it away, wrapping it in wicker until it disappeared. Ian fell backward, winning free of the trap but barely catching himself before he fell. Elsa watched with a frown as he scrambled to find his footing.

“My hero,” she muttered.

“That didn’t go as planned.”

“No?” she said. “And here I thought your goal was to be caught here with me, that we might spend eternity in this nightmare.” She closed her eyes and leaned back, sighing mightily. “The horses had the right of it.”

“I’ll find the gheist,” Ian insisted. “I’ll get him to let us go.”

“Without so much as a knife? Perhaps you can trick him with your clever wordplay.”

“I’ll think of something.”

“Yes,” Elsa said. “I’m sure you will.”

He grimaced, and started climbing again. Quickly the fog hid Elsa from his sight. He climbed for what felt like an eternity, and then he climbed some more.

Elsa’s tangled cage came into view again.

He looked around and there, just to one side, was the tree of dead Tenerrans, looking more wasted than before. He was going in circles, and time was moving in ways that made no sense. Ian settled against the nearest trunk and closed his eyes. He wondered why he wasn’t tired, or if maybe he was so tired that he couldn’t tell the difference. He stared at the swirling fog where the tree’s canopy should be, and then he realized that his eyes were closed, but he could still see.

He opened his eyes. Nothing changed.

“Night,” he whispered to himself. “Night and the land of dreams… and so the logic of dreams.”

Ian shimmied along the trunk toward where the canopy should be, getting closer and closer to the fog. The tree branched, the limbs getting thinner and thinner until they creaked under Ian’s weight. A crown of dry leaves shook free, spinning down into the distance. He reached the tip of the tree. There was nothing beyond it but fog.

So he jumped.

5

THE STONES WERE stained with the blood of the choir. Rough rows of barrels and broken wood served as pews, while the altar had mostly survived the attack of the feral god. There was still much work to be done.