0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Andura Publishing

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

Experience the life-changing power of William James with this unforgettable book.

Das E-Book wird angeboten von und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Letters of William James, Vol. II

by William James

CONTENTS

XI. 1893-1899 1-52

_Turning to Philosophy--A Student's Impressions--Popular

Lecturing--Chautauqua._

LETTERS:--

To Dickinson S. Miller 17

To Henry Holt 19

To Henry James 20

To Henry James 20

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 20

To G. H. Howison 22

To Theodore Flournoy 23

To his Daughter 25

To E. L. Godkin 28

To F. W. H. Myers 30

To F. W. H. Myers 32

To Henry Holt 33

To his Class at Radcliffe College 33

To Henry James 34

To Henry James 36

To Benjamin P. Blood 38

To Mrs. James 40

To Miss Rosina H. Emmet 44

To Charles Renouvier 44

To Theodore Flournoy 46

To Dickinson S. Miller 48

To Henry James 51

XII. 1893-1899 (Continued) 53-91

_The Will to Believe--Talks to Teachers--Defense of Mental

Healers--Excessive Climbing in the Adirondacks._

LETTERS:--

To Theodore Flournoy 53

To Henry W. Rankin 56

To Benjamin P. Blood 58

To Henry James 60

To Miss Ellen Emmet 62

To E. L. Godkin 64

To F. C. S. Schiller 65

To James J. Putnam 66

To James J. Putnam 72

To François Pillon 73

To Mrs. James 75

To G. H. Howison 79

To Henry James 80

To his Son Alexander 81

To Miss Rosina H. Emmet 82

To Dickinson S. Miller 84

To Dickinson S. Miller 86

To Henry Rutgers Marshall 86

To Henry Rutgers Marshall 88

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 88

XIII. 1899-1902 92-170

_Two Years of Illness in Europe--Retirement from Active Duty at

Harvard--The First and Second Series of the Gifford Lectures._

LETTERS:--

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 95

To Mrs. E. P. Gibbens 96

To William M. Salter 99

To Miss Frances R. Morse 102

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 103

To Thomas Davidson 106

To John C. Gray 108

To Miss Frances R. Morse 109

To Mrs. Glendower Evans 112

To Dickinson S. Miller 115

To Francis Boott 117

To Hugo Münsterberg 119

To G. H. Palmer 120

To Miss Frances R. Morse 124

To his Son Alexander 129

To his Daughter 130

To Miss Frances R. Morse 133

To Miss Frances R. Morse 133

To Josiah Royce 135

To Miss Frances R. Morse 138

To James Sully 140

To Miss Frances R. Morse 142

To F. C. S. Schiller 142

To Miss Frances R. Morse 143

To Miss Frances R. Morse 146

To Henry W. Rankin 148

To Charles Eliot Norton 150

To N. S. Shaler 153

To Miss Frances R. Morse 155

To Henry James 159

To E. L. Godkin 159

To E. L. Godkin 161

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 162

To H. N. Gardiner 164

To F. C. S. Schiller 164

To Charles Eliot Norton 166

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 167

XIV. 1902-1905 171-218

_The Last Period (I)--Statements of Religious Belief--Philosophical

Writing._

LETTERS:--

To Henry L. Higginson 173

To Miss Grace Norton 173

To Miss Frances R. Morse 175

To Henry L. Higginson 176

To Henri Bergson 178

To Mrs. Louis Agassiz 180

To Henry L. Higginson 182

To Henri Bergson 183

To Theodore Flournoy 185

To Henry James 188

To his Daughter 192

To Miss Frances R. Morse 193

To Henry James 195

To Henry W. Rankin 196

To Dickinson S. Miller 197

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 198

To Miss Frances R. Morse 200

To Mrs. Henry Whitman 201

To Henry James 202

To François Pillon 203

To Henry James 204

To Charles Eliot Norton 206

To L. T. Hobhouse 207

To Edwin D. Starbuck 209

To James Henry Leuba 211

Answers to the Pratt Questionnaire on Religious Belief 212

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 215

To F. C. S. Schiller 216

To F. J. E. Woodbridge 217

To Edwin D. Starbuck 217

To F. J. E. Woodbridge 218

XV. 1905-1907 219-282

_The Last Period (II)--Italy and Greece--Philosophical Congress in

Rome--Stanford University--The Earthquake--Resignation of

Professorship._

LETTERS:--

To Mrs. James 221

To his Daughter 223

To Mrs. James 225

To George Santayana 228

To Mrs. James 229

To Mrs. James 230

To H. G. Wells 230

To Henry L. Higginson 231

To T. S. Perry 232

To Dickinson S. Miller 233

To Dickinson S. Miller 235

To Dickinson S. Miller 237

To Daniel Merriman 238

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 238

To Henry James 239

To Theodore Flournoy 241

To F. C. S. Schiller 245

To Miss Frances R. Morse 247

To Henry James and W. James, Jr. 250

To W. Lutoslawski 252

To John Jay Chapman 255

To Henry James 258

To H. G. Wells 259

To Miss Theodora Sedgwick 260

To his Daughter 262

To Henry James and W. James, Jr. 263

To Moorfield Storey 265

To Theodore Flournoy 266

To Charles A. Strong 268

To F. C. S. Schiller 270

To Clifford W. Beers 273

To William James, Jr. 275

To Henry James 277

To F. C. S. Schiller 280

XVI. 1907-1909 283-332

_The Last Period (III)--Hibbert Lectures in Oxford--The Hodgson Report._

LETTERS:--

To Charles Lewis Slattery 287

To Henry L. Higginson 288

To W. Cameron Forbes 288

To F. C. S. Schiller 290

To Henri Bergson 290

To T. S. Perry 294

To Dickinson S. Miller 295

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 296

To W. Jerusalem 297

To Henry James 298

To Theodore Flournoy 300

To Norman Kemp Smith 301

To his Daughter 301

To Henry James 302

To Henry James 303

To Miss Pauline Goldmark 303

To Charles Eliot Norton 306

To Henri Bergson 308

To John Dewey 310

To Theodore Flournoy 310

To Shadworth H. Hodgson 312

To Theodore Flournoy 313

To Henri Bergson 315

To H. G. Wells 316

To Henry James 317

To T. S. Perry 318

To Hugo Münsterberg 320

To John Jay Chapman 321

To G. H. Palmer 322

To Theodore Flournoy 322

To Miss Theodora Sedgwick 324

To F. C. S. Schiller 325

To Theodore Flournoy 326

To Shadworth H. Hodgson 328

To John Jay Chapman 329

To John Jay Chapman 330

To John Jay Chapman 330

To Dickinson S. Miller 331

XVII. 1910 333-350

_Final Months--The End._

LETTERS:--

To Henry L. Higginson 334

To Miss Frances R. Morse 335

To T. S. Perry 335

To François Pillon 336

To Theodore Flournoy 338

To his Daughter 338

To Henry P. Bowditch 341

To François Pillon 342

To Henry Adams 344

To Henry Adams 346

To Henry Adams 347

To Benjamin P. Blood 347

To Theodore Flournoy 349

APPENDIX I. 353

Three Criticisms for Students.

APPENDIX II. 357

Books by William James.

INDEX 363

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

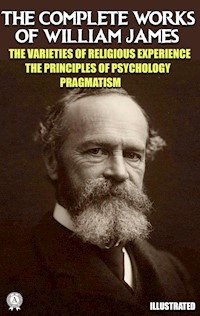

William James in middle life _Frontispiece_

"Damn the Absolute": two snapshots of William

James and Josiah Royce 135

William James and Henry James posing for a

kodak in 1900 161

William James and Henry Clement at the "Putnam

Shanty" in the Adirondacks (1907?) 315

Facsimile of Post-card addressed to Henry Adams 347

THE LETTERS OF WILLIAM JAMES

XI

1893-1899

_Turning to Philosophy--A Student's Impressions--Popular

Lecturing--Chautauqua_

When James returned from Europe, he was fifty-two years old. If he had

been another man, he might have settled down to the intensive

cultivation of the field in which he had already achieved renown and

influence. He would then have spent the rest of his life in working out

special problems in psychology, in deducing a few theories, in making

particular applications of his conclusions, in administering a growing

laboratory, in surrounding himself with assistants and disciples--in

weeding and gathering where he had tilled. But the fact was that the

publication of his two books on psychology operated for him as a welcome

release from the subject.

He had no illusion of finality about what he had written.[1] But he

would have said that whatever original contribution he was capable of

making to psychology had already been made; that he must pass on and

leave addition and revision to others. He gradually disencumbered

himself of responsibility for teaching the subject in the College. The

laboratory had already been placed under Professor Münsterberg's charge.

For one year, during which Münsterberg returned to Germany, James was

compelled to direct its conduct; but he let it be known that he would

resign his professorship rather than concern himself with it

indefinitely.

Readers of this book will have seen that the centre of his interest had

always been religious and philosophical. To be sure, the currents by

which science was being carried forward during the sixties and seventies

had supported him in his distrust of conclusions based largely on

introspection and _a priori_ reasoning. As early as 1865 he had said,

apropos of Agassiz, "No one sees farther into a generalization than his

own knowledge of details extends." In the spirit of that remark he had

spent years on brain-physiology, on the theory of the emotions, on the

feeling of effort in mental processes, in studying the measurements and

exact experiments by means of which the science of the mind was being

brought into quickening relation with the physical and biological

sciences. But all the while he had been driven on by a curiosity that

embraced ulterior problems. In half of the field of his consciousness

questions had been stirring which now held his attention completely.

Does consciousness really exist? Could a radically empirical conception

of the universe be formulated? What is knowledge? What truth? Where is

freedom? and where is there room for faith? Metaphysical problems

haunted his mind; discussions that ran in strictly psychological

channels bored him. He called psychology "a nasty little subject,"

according to Professor Palmer, and added, "all one cares to know lies

outside." He would not consider spending time on a revised edition of

his textbook (the "Briefer Course") except for a bribe that was too

great ever to be urged upon him. As time went on, he became more and

more irritated at being addressed or referred to as a "psychologist." In

June, 1903, when he became aware that Harvard was intending to confer an

honorary degree on him, he went about for days before Commencement in a

half-serious state of dread lest, at the fatal moment, he should hear

President Eliot's voice naming him "Psychologist, psychical researcher,

willer-to-believe, religious experiencer." He could not say whether the

impossible last epithets would be less to his taste than "psychologist."

Only along the borderland between normal and pathological mental states,

and particularly in the region of "religious experience," did he

continue to collect psychological data and to explore them.

The new subjects which he offered at Harvard during the nineties are

indicative of the directions in which his mind was moving. In the first

winter after his return he gave a course on Cosmology, which he had

never taught before and which he described in the department

announcement as "a study of the fundamental conceptions of natural

science with especial reference to the theories of evolution and

materialism," and for the first time announced that his graduate

"seminar" would be wholly devoted to questions in mental pathology

"embracing a review of the principal forms of abnormal or exceptional

mental life." In 1895 the second half of his psychological seminar was

announced as "a discussion of certain theoretic problems, as

Consciousness, Knowledge, Self, the relations of Mind and Body." In 1896

he offered a course on the philosophy of Kant for the first time. In

1898 the announcement of his "elective" on Metaphysics explained that

the class would consider "the unity or pluralism of the world ground,

and its knowability or unknowability; realism and idealism, freedom,

teleology and theism."[2]

But there is another aspect of the nineties which must be touched upon.

After getting back "to harness" in 1893 James took up, not only his full

college duties, but an amount of outside lecturing such as he had never

done before. In so doing he overburdened himself and postponed the

attainment of his true purpose; but the temptation to accept the

requests which now poured in on him was made irresistible by practical

considerations. He not only repeated some of his Harvard courses at

Radcliffe College, and gave instruction in the Harvard Summer School in

addition to the regular work of the term; but delivered lectures at

teachers' meetings and before other special audiences in places as far

from Cambridge as Colorado and California. A number of the papers that

are included in "The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular

Philosophy" (1897) and "Talks to Teachers and Students on Some of Life's

Ideals" (1897) were thus prepared as lectures. Some of them were read

many times before they were published. When he stopped for a rest in

1899, he was exhausted to the verge of a formidable break-down.

Even a glance at this period tempts one to wonder whether this record

would not have been richer if it had been different. Might-have-beens

can never be measured or verified; and yet sometimes it cannot be

doubted that possibilities never realized were actual possibilities

once. By 1893 James was inwardly eager, as has already been said, to

devote all his thought and working time to metaphysical and religious

questions. More than that--he had already conceived the important terms

of his own _Welt-anschauung_. "The Will to Believe" was written by 1896.

In the preface to the "Talks to Teachers" he said of the essay called "A

Certain Blindness in Human Beings," "it connects itself with a definite

view of the World and our Moral relations to the same.... I mean the

pluralistic or individualistic philosophy." This was no more than a

statement of a general philosophic attitude which had for some years

been familiar to his students and to readers of his occasional papers.

The lecture on "Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results,"

delivered at the University of California in 1898, forecast "Pragmatism"

and the "Meaning of Truth." If his time and energy had not been

otherwise consumed, the nineties might well have witnessed the

appearance of papers which were not written until the next decade. If he

had been able to apply an undistracted attention to what his spirit was

all the while straining toward, the disastrous breakdown of 1899-1902

might not have happened. But instead, these best years of his maturity

were largely sacrificed to the practical business of supporting his

family. His salary as a Harvard professor was insufficient to his needs.

On his salary alone he could not educate his four children as he wanted

to, and make provision for his old age and their future and his wife's,

except by denying himself movement and social and professional contacts

and by withdrawing into isolation that would have been utterly

paralyzing and depressing to his genius. He possessed private means, to

be sure; but, considering his family, these amounted to no more than a

partial insurance against accident and a moderate supplement to his

salary. His books had not yet begun to yield him a substantial increase

of income. It is true that he made certain lecture engagements serve as

the occasion for casting philosophical conceptions in more or less

popular form, and that he frequently paid the expenses of refreshing

travels by means of these lectures. But after he had economized in every

direction,--as for instance, by giving up horse and hired man at

Chocorua,--the bald fact remained that for six years he spent most of

the time that he could spare from regular college duties, and about all

his vacations, in carrying the fruits of the previous fifteen years of

psychological work into the popular market. His public reputation was

increased thereby. Teachers, audiences, and the "general reader" had

reason to be thankful. But science and philosophy paid for the gain. His

case was no worse than that of plenty of other men of productive genius

who were enmeshed in an inadequately supported academic system. It would

have been much more distressing under the conditions that prevail today.

So James took the limitations of the situation as a matter of course and

made no complaint. But when he died, the systematic statement of his

philosophy had not been "rounded out" and he knew that he was leaving it

"too much like an arch built only on one side."

* * * * *

James's appearance at this period is well shown by the frontispiece of

this volume. Almost anyone who was at Harvard in the nineties can recall

him as he went back and forth in Kirkland Street between the College and

his Irving Street house, and can in memory see again that erect figure

walking with a step that was somehow firm and light without being

particularly rapid, two or three thick volumes and a note-book under

one arm, and on his face a look of abstraction that used suddenly to

give way to an expression of delighted and friendly curiosity. Sometimes

it was an acquaintance who caught his eye and received a cordial word;

sometimes it was an occurrence in the street that arrested him;

sometimes the terrier dog, who had been roving along unwatched and

forgotten, embroiled himself in an adventure or a fight and brought

James out of his thoughts. One day he would have worn the Norfolk jacket

that he usually worked in at home to his lecture-room; the next, he

would have forgotten to change the black coat that he had put on for a

formal occasion. At twenty minutes before nine in the morning he could

usually be seen going to the College Chapel for the fifteen-minute

service with which the College day began. If he was returning home for

lunch, he was likely to be hurrying; for he had probably let himself be

detained after a lecture to discuss some question with a few of his

class. He was apt then to have some student with him whom he was

bringing home to lunch and to finish the discussion at the family table,

or merely for the purpose of establishing more personal relations than

were possible in the class-room. At the end of the afternoon, or in the

early evening, he would frequently be bicycling or walking again. He

would then have been working until his head was tired, and would have

laid his spectacles down on his desk and have started out again to get a

breath of air and perhaps to drop in on a Cambridge neighbor.

In his own house it seemed as if he was always at work; all the more,

perhaps, because it was obvious that he possessed no instinct for

arranging his day and protecting himself from interruptions. He managed

reasonably well to keep his mornings clear; or rather he allowed his

wife to stand guard over them with fair success. But soon after he had

taken an essential after-lunch nap, he was pretty sure to be "caught" by

callers and visitors. From six o'clock on, he usually had one or two of

the children sitting, more or less subdued, in the library, while he

himself read or dashed off letters, or (if his eyes were tired) dictated

them to Mrs. James. He always had letters and post-cards to write. At

any odd time--with his overcoat on and during a last moment before

hurrying off to an appointment or a train--he would sit down at his desk

and do one more note or card--always in the beautiful and flowing hand

that hardly changed between his eighteenth and his sixty-eighth years.

He seemed to feel no need of solitude except when he was reading

technical literature or writing philosophy. If other members of the

household were talking and laughing in the room that adjoined his study,

he used to keep the door open and occasionally pop in for a word, or to

talk for a quarter of an hour. It was with the greatest difficulty that

Mrs. James finally persuaded him to let the door be closed up. He never

struck an equilibrium between wishing to see his students and neighbors

freely and often, and wishing not to be interrupted by even the most

agreeable reminder of the existence of anyone or anything outside the

matter in which he was absorbed.

It was customary for each member of the Harvard Faculty to announce in

the college catalogue at what hour of the day he could be consulted by

students. Year after year James assigned the hour of his evening meal

for such calls. Sometimes he left the table to deal with the caller in

private; sometimes a student, who had pretty certainly eaten already and

was visibly abashed at finding himself walking in on a second dinner,

would be brought into the dining-room and made to talk about other

things than his business.

He allowed his conscience to be constantly burdened with a sense of

obligation to all sorts of people. The list of neighbors, students,

strangers visiting Cambridge, to whom he and Mrs. James felt responsible

for civilities, was never closed, and the cordiality which animated his

intentions kept him reminded of every one on it.

And yet, whenever his wife wisely prepared for a suitable time and made

engagements for some sort of hospitality otherwise than by hap-hazard,

it was perversely likely to be the case, when the appointed hour

arrived, that James was "going on his nerves" and in no mood for "being

entertaining." The most comradely of men, nothing galled him like

_having to be_ sociable. The "hollow mockery of our social conventions"

would then be described in furious and lurid speech. Luckily the guests

were not yet there to hear him. But they did not always get away without

catching a glimpse of his state of mind. On one such occasion,--an

evening reception for his graduate class had been arranged,--Mrs. James

encountered a young man in the hall whose expression was so perturbed

that she asked him what had happened to him. "I've come in again," he

replied, "to get my hat. I was trying to find my way to the dining-room

when Mr. James swooped at me and said, 'Here, Smith, you want to get out

of this _Hell_, don't you? I'll show you how. There!' And before I could

answer, he'd popped me out through a back-door. But, really, I do not

want to go!"

The dinners of a club to which allusions will occur in this volume, (in

letters to Henry L. Higginson, T. S. Perry, and John C. Gray) were

occasions apart from all others; for James could go to them at the last

moment, without any sense of responsibility and knowing that he would

find congenial company and old friends. So he continued to go to these

dinners, even after he had stopped accepting all invitations to dine.

The Club (for it never had any name) had been started in 1870. James had

been one of the original group who agreed to dine together once a month

during the winter. Among the other early members had been his brother

Henry, W. D. Howells, O. W. Holmes, Jr., John Fiske, John C. Gray, Henry

Adams, T. S. Perry, John C. Ropes, A. G. Sedgwick, and F. Parkman. The

more faithful diners, who constituted the nucleus of the Club during the

later years, included Henry L. Higginson, Sturgis Bigelow, John C.

Ropes, John T. Morse, Charles Grinnell, James Ford Rhodes, Moorfield

Storey, James W. Crafts, and H. P. Walcott.

* * * * *

Every little while James's sleep would "go to pieces," and he would go

off to Newport, the Adirondacks, or elsewhere, for a few days. This

happened both summer and winter. It was not the effect of the place or

climate in which he was living, but simply that his dangerously high

average of nervous tension had been momentarily raised to the snapping

point. Writing was almost certain to bring on this result. When he had

an essay or a lecture to prepare, he could not do it by bits. In order

to begin such a task, he tried to seize upon a free day--more often a

Sunday than any other. Then he would shut himself into his library, or

disappear into a room at the top of the house, and remain hidden all

day. If things went well, twenty or thirty sheets of much-corrected

manuscript (about twenty-five hundred words in his free hand) might

result from such a day. As many more would have gone into the

waste-basket. Two or three successive days of such writing "took it out

of him" visibly.

Short holidays, or intervals in college lecturing, were often employed

for writing in this way, the longer vacations of the latter nineties

being filled, as has been said, with traveling and lecture engagements.

In the intervals there would be a few days, or sometimes two or three

whole weeks, at Chocorua. Or, one evening, all the windows of the

deserted Irving Street house would suddenly be wide open to the night

air, and passers on the sidewalk could see James sitting in his

shirt-sleeves within the circle of the bright light that stood on his

library table. He was writing letters, making notes, and skirmishing

through the piles of journals and pamphlets that had accumulated during

an absence.

* * * * *

The impression which he made on a student who sat under him in several

classes shortly before the date at which this volume begins have been

set down in a form in which they can be given here.

"I have a vivid recollection" (writes Dr. Dickinson S. Miller) "of

James's lectures, classes, conferences, seminars, laboratory interests,

and the side that students saw of him generally. Fellow-manliness seemed

to me a good name for his quality. The one thing apparently impossible

to him was to speak _ex cathedra_ from heights of scientific erudition

and attainment. There were not a few 'if's' and 'maybe's' in his

remarks. Moreover he seldom followed for long an orderly system of

argument or unfolding of a theory, but was always apt to puncture such

systematic pretensions when in the midst of them with some entirely

unaffected doubt or question that put the matter upon a basis of common

sense at once. He had drawn from his laboratory experience in chemistry

and his study of medicine a keen sense that the imposing formulas of

science that impress laymen are not so 'exact' as they sound. He was

not, in my time at least, much of a believer in lecturing in the sense

of continuous exposition.

"I can well remember the first meeting of the course in psychology in

1890, in a ground-floor room of the old Lawrence Scientific School. He

took a considerable part of the hour by reading extracts from Henry

Sidgwick's Lecture against Lecturing, proceeding to explain that we

should use as a textbook his own 'Principles of Psychology,' appearing

for the first time that very week from the press, and should spend the

hours in conference, in which we should discuss and ask questions, on

both sides. So during the year's course we read the two volumes through,

with some amount of running commentary and controversy. There were four

or five men of previous psychological training in a class of (I think)

between twenty and thirty, two of whom were disposed to take up cudgels

for the British associational psychology and were particularly troubled

by the repeated doctrine of the 'Principles' that a state of

consciousness had no parts or elements, but was one indivisible fact. He

bore questions that really were criticisms with inexhaustible patience

and what I may call (the subject invites the word often) _human_

attention; invited written questions as well, and would often return

them with a reply penciled on the back when he thought the discussion

too special in interest to be pursued before the class. Moreover, he

bore with us with never a sign of impatience if we lingered after class,

and even walked up Kirkland Street with him on his way home. Yet he was

really not argumentative, not inclined to dialectic or pertinacious

debate of any sort. It must always have required an effort of

self-control to put up with it. He almost never, even in private

conversation, contended for his own opinion. He had a way of often

falling back on the language of perception, insight, sensibility, vision

of possibilities. I recall how on one occasion after class, as I parted

with him at the gate of the Memorial Hall triangle, his last words were

something like these: 'Well, Miller, that theory's not a warm reality to

me yet--still a cold conception'; and the charm of the comradely smile

with which he said it! The disinclination to formal logical system and

the more prolonged purely intellectual analyses was felt by some men as

a lack in his classroom work, though they recognized that these analyses

were present in the 'Psychology.' On the other hand, the very tendency

to _feel_ ideas lent a kind of emotional or æsthetic color which

deepened the interest.

"In the course of the year he asked the men each to write some word of

suggestion, if he were so inclined, for improvement in the method with

which the course was conducted; and, if I remember rightly, there were

not a few respectful suggestions that too much time was allowed to the

few wrangling disputants. In a pretty full and varied experience of

lecture-rooms at home and abroad I cannot recall another where the class

was asked to criticize the methods of the lecturer.

"Another class of twelve or fourteen, in the same year, on Descartes,

Spinoza, and Leibnitz, met in one of the 'tower rooms' of Sever Hall,

sitting around a table. Here we had to do mostly with pure metaphysics.

And more striking still was the prominence of humanity and sensibility

in his way of taking philosophic problems. I can see him now, sitting at

![A Pluralistic Universe [Halls of Wisdom] - William James - E-Book](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/417cf18ca0d020e7eb589b5daad74b5f/w200_u90.jpg)