4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

The Merry Muses of Caledonia is among Burns' best known, but least read, work. This collection of bawdy poems, some written by and some collected by Burns, ranges from celebrations of spirited women in "Ellibanks", to misogyny in "There was twa wives" and male fantasy in "Nine Inch will please a lady". These engaging poems are not lewd or distasteful but possess a great wit and charm. This new edition updates the 1959 printing, which with engaging accompanying material by James Barke and preface by J. De Lancey Ferguson have made this the definitive version, until now. "The Merry Muses" was always intended to be accompanied by music but the 1959 edition was left incomplete due to Barke's premature death. For the first time the book is completed as it was always meant to be with notes to the tunes created with reference to Barke's unpublished papers. "The Luath Merry Muses" edition also includes bonus material with specially commissioned illustrations from top political satirist Bob Dewar and an introduction by Burns scholar Valentina Bold. Ferguson's work is brought up to date with commentary on the latest critical responses. This new edition will make this classic of Burns' literature more accessible to modern readers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

ROBERT BURNS (1759–96) was born in Alloway, Ayrshire, the son of a tenant farmer. He was raised and educated there, and at Mount Oliphant and Lochlie. Burns worked as a flax dresser in Irvine between 1781 and 1782, returning to farming at Lochlie and, from 1784 at Mossgiel, with his brother Gilbert. After the success of the Kilmarnock edition ofPoems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect(1786), Burns spent a period of time in Edinburgh; the Edinburgh edition followed in 1787. After the Border and Highland tours of 1787 he returned to Edinburgh, and began contributing to James Johnson’sScots Musical Museum(1787–1803) and, later, to George Thomson’sCollection of Original Scottish Airs(1793–1841). In 1788 Burns moved to Ellisland in Dumfriesshire, holding the lease until 1791, when he took up an Excise post in Dumfries. His colourful biography and complex love-life – from early romances with Betty Paton and ‘Highland Mary’ Campbell, later liaisons with women including, possibly, Agnes McLehose, to his marriage to Jean Armour – has often distracted attention from his work, as has Henry Mackenzie’s characterisation of Burns (with which the poet collaborated) as the ‘Heaven-taught ploughman’. However, Burns’s role as Scotland’s ‘National Bard’ is balanced by his international reputation. His poetry and songs, expressed in the Scots and English languages, include humorous pieces, often based on Scottish traditions, like ‘Tam o’ Shanter’; dismissals of religious hypocrisy, like ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’; compassionate pieces like ‘Westlin Winds’ and ‘To a Mouse’; considerations of working class life, like ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ and lyrics of love in its various moods, from ‘A Red red rose’ to ‘The Banks o’ Doon’. Politicised pieces, reflecting the complexity of his opinions, range from ‘For a’ that and a’ that’ to ‘The Rights of Woman’.The Merry Muses of Caledoniawas published posthumously, without Burns’s authorisation.

JAMES BARKE (1906–58) was born in Torwoodlee, Galashiels and raised in Tulliallan in Fife, with strong connexions to rural Galloway. He worked in Glasgow, became a full-time novelist and dramatist, associated with the Unity Theatre, and ran a hotel in Ayrshire, returning to Glasgow in 1955. Barke’s novels includeThe World his Pillow(1933),Major Operation(1936) andThe Land of the Leal(1939). He is best known for his five-part historical novel about the life of Robert Burns,The Immortal Memory(1946–54), includingThe Wind that Shakes the Barley(1946),The Song in the Greenthorn Tree(1947),The Wonder of All the Gay World(1949),The Crest of the Broken Wave(1953) andThe Well of the Silent Harp(1954), with an accompanying novel on Jean ArmourBonnie Jean(1959). He also editedPoems and Songs of Robert Burns(1955) and was an expert onpiobaireachd.

SYDNEY GOODSIR SMITH (1915–75) was born in Wellington, New Zealand, and moved in 1928 to Edinburgh, where his father was Chair of Forensic Medicine at the University. Educated at the Universities of Edinburgh and Oxford, he is best known for his poetry in Scots, including his masterpiece on love,Under the Eildon Tree(1948). Other poetry includesThe Deevil’s Waltz(1946),So Late into the Night(1952) andFigs and Thistles(1959). His plays includeThe Wallace(1960), performed at the Edinburgh Festival, andThe Rut of Spring(1949–50). Other work includes the comic novelCarotid Cornucopius(1947) and, as editor,Robert Fergusson1750–1744 (1952) andHugh MacDiarmid: a Festschrift(1962) with Kulgin Duval. In addition toThe Merry Muses, he editedA Choice of Burns’s Poems and Songs(1966), and he was a talented artist, art critic, and translator of writers including Alexander Blok.

JOHN DeLANCEY FERGUSON (1888–1966) was born in Scottsville, New York. His father, a veteran of the Civil War, was rector of Grace Episcopal Church, and an immigrant from Portadown, Northern Ireland; his mother was the daughter of immigrants from Lurgan. Raised in Plainfield, New Jersey, he was educated at Rutgers University and Columbia University, publishing his PhD thesisAmerican LiTerature in Spain(1916). Ferguson taught at Heidelberg College, Ohio Wesleyan and was a professor at Brooklyn College, New York, retiring in 1954. He is probably best known for his edition of theLetters of Robert Burns(1931), revised in 1985 by G. Ross Roy, and for his biographyPride and Passion: Robert Burns, 1759–1796(1939). His publications includeMark Twain, Man and Legend(1965),Theme and Variation in the Short Story(1938) and, as editor,RLS: Stevenson’s Letters to Charles Baxter(1956), with Marshall Waingrow.

VALENTINA BOLD was born in Edinburgh in 1964, grew up in Balbirnie in Fife, and was educated at the University of Edinburgh, Memorial University of Newfoundland and the University of Glasgow. She has worked at the University of Glasgow’s Dumfries campus since it opened in 1999, heading the Scottish Studies programme and running the taught M.Litts in ‘Robert Burns Studies’ and ‘Scottish Cultural Heritage’. Her publications include a CD-romNorthern Folk: Living Traditions of North East Scotland(1999), with Tom McKean;Smeddum: A Lewis Grassic Gibbon Anthology(2001) andJames Hogg: A Bard of Nature’s Making(2007). She is currently editing James Hogg’sThe Brownie of Bodsbeckfor the Stirling–South CarolinaThe Collected Works of James Hoggedition, andThe Kitty Hartley Manuscript: Scots Songs from Scotch Corner, and is general editor of ‘The History and Culture of Scotland’ series for Peter Lang.

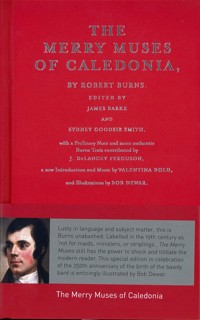

THE

MERRY MUSES OF CALEDONIA,

BY ROBERT BURNS.

EDITED BY

JAMES BARKE

AND

SYDNEY GOODSIR SMITH,

with a Prefatory Note and some authentic Burns Texts contributed by

J. DeLANCEY FERGUSON.

a new Introduction and some music score annotations by

VALENTINA BOLD,

and illustrations by

BOB DEWAR.

PUBLISHED BY THE LUATH PRESS.

MM,IX.

First publishedc.1799

Bicentenary edition edited by James Barke and Sydney Goodsir Smith, with a Prefatory Note and some authentic Burns Texts contributed by J. DeLancey Ferguson, first published by Macdonald Printers, Edinburgh in 1959

Luath edition 2009

eBook of this edition 2014

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-68-4

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-78-6

Design by Tom Bee

© Luath Press Ltd 2014

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction: The Elusive Text by Valentina Bold

Foreword by Sydney Goodsir Smith

Sources and Texts of The Suppressed Poems by J. DeLancey Ferguson

Pornography and Bawdry in Literature and Society by James Barke

Burns and The Merry Muses: Introductory by Sydney Goodsir Smith

Abbreviations

I Songs in Burns’s Holograph A. BY BURNS

I’ll Tell you a Tale of a Wife

Bonie Mary

Act Sederunt of the Session

When Princes and Prelates

While Prose-Work and Rhymes

Nine Inch will Please a Lady

Ode to Spring

O Saw ye my Maggie?

To Alexander Findlater

The Fornicator

My Girl She’s Airy

There Was Twa Wives

B. COLLECTED BY BURNS

Brose an’ Butter

Cumnock Psalms

Green Grow the Rashes O [A]

Muirland Meg

Todlen Hame

Wap and Row

There Cam a Soger

Sing, Up wi’t, Aily

Green Sleeves

From Printed Sources

II BY OR ATTRIBUTED TO BURNS

The Patriarch

The Bonniest Lass

Godly Girzie

Wha’ll Mow me Now?

Had I the Wyte [A]

Dainty Davie [A]

The Trogger

Put Butter in my Donald s Brose

Here’s his Health in Water

The Jolly Gauger

O Gat ye me wi Naething

Gie the Lass her Fairin’

Green Grow the Rashes O [B]

Tail Todle

I Rede ye Beware o’ the Ripples

Our John’s Brak Yestreen

Grizzel Grimme

Two Epitaphs

III OLD SONGS USED BY BURNS FOR POLITE VERSIONS

[Songs from sources other thanThe Merry Musesare listed first]

Had I the Wyte [B]

Dainty Davie [B]

Let me in this ae Night

The Tailor

Eppie McNab

Duncan Gray

Logan Water

The Mill, Mill-O

My ain kind Dearie

She Rose and Loot me in

The Cooper o’ Dundee

Ye hae Lien wrang, Lassie

Will ye na, Can ye na, Let me be

Ellibanks

Comin’ o’er the Hills o’ Coupar

Comin’ thro’ the Rye

As I cam o’er the Cairney Mount

John Anderson, my Jo

Duncan Davidson

The Ploughman

How can I keep my Maidenhead?

Andrew an’ his Cuttie Gun

O can ye Labour lee, young Man?

Wad ye do that?

There cam a Cadger

Jenny Macraw

IV COLLECTED BY BURNS

The Reels o’ Bogie

Jockey was a Bonny Lad

Blyth Will an’ Bessie’s Wedding

The Lass o’ Liviston

She’s Hoy’d me out o’ Lauderdale

Errock Brae

Our Gudewife’s sae Modest

Supper is na Ready

Yon, yon, yon, Lassie

The Yellow, Yellow Yorlin’

She Gripet at the Girtest o’t

Ye’se get a Hole to hide it in

Duncan Macleerie

They took me to the Haly Band

The Modiewark

Ken ye na our Lass, Bess?

Wha the Deil can Hinder the Wind to Blaw?

We’re a’ gaun Southie O

Cuddie the Cooper

Nae Hair on’t

There’s Hair on’t

The Lassie Gath’ring Nits

The Linkin’ Laddie

Johnie Scott

Madgie cam to my Bedstock

O gin I had her

He till’t and She till’t

V ALIEN MODES

Tweedmouth Town

The Bower of Bliss

The Plenipotentiary

Una’s Lock

VI THE LIBEL SUMMONS

Songs by Burns, with Music by Valentina Bold

Further Reading: A Selected List

Glossary by Sydney Goodsir Smith

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

IAM grateful to Alasdair Barke, Kitty Pal, John Calder and Jane Ferguson Blanshard for their kind permission to include copyright material from the 1959 edition ofTheMerry Muses of Caledonia, edited by James Barke, Sydney Goodsir Smith and John DeLancey Ferguson, along with the glossary by Sydney Goodsir Smith, and to Tessa Ransford on behalf of M. Macdonald. I would like to thank The Mitchell Library, who gave permission to include manuscript references from the ‘James Barke Papers’ in Special Collections; the National Library of Scotland, for permission to quote from the ‘Sydney Goodsir Smith’ Papers; Edinburgh University Library for permission to quote from the ‘Sydney Goodsir Smith’ Collection; the University of Delaware’s department of Special Collections, for permission to quote from the ‘Sydney Goodsir Smith’ Papers; Broughton House, for permission to quote from the Ewing correspondence and the Andrew Carnegie Library, Dunfermline, for permission to cite the Ewing transcript of the 1799 edition ofThe Merry Muses of Caledonia.

I would particularly like to thank the following people, who offered me valuable assistance in locating and consulting library materials: Jim Allen of the Hornel Library, Broughton House, Kirkcudbright; Sally Harrower and George Stanley of the National Library of Scotland; Ruth Airley and Neil Moffat of the Ewart Library, Dumfries; Tricia Boyd of Edinburgh University Library; Christine Henderson of the Mitchell Library; Iris Snyder of Special Collections at the University of Delaware’s library; Janice Erskine at the Andrew Carnegie Library, Dunfermline; Nancy Groce and Steve Winnick of the American Folklife Center at Library of Congress; Larissa Watkin of the Library at the Grand Masonic Temple in Washington, as well as my colleagues Avril Goodwin, Jan O’Callaghan and John Macdonald at the University of Glasgow’s Dumfries Campus Library.

Ross Roy, Gerry Carruthers, John Manson, Ed Cray and Tom Hall all helped in substantial ways. I am grateful, too, to the Globe Inn, Dumfries, which kindly lent me its copy of the 1911 edition, and particularly to Maureen McKerrow and Jane Brown. I would like to thank Fred Freeman, Sheena Wellington and Karine Polwart for sharing their insights into musical aspects of Burns’s songs; all the misunderstandings, of course, are wholly my own. I would like to thank David Nicol, Alice Bold, Aileen McGuigan and Carol Hill for their encouragement and supportiveness, along with Gavin MacDougall, Leila Cruickshank, Catriona Wallace and all of the team at Luath. The one missing person from this list is my father, Alan Bold, whose scholarship and kindness is a lasting source of inspiration.

INTRODUCTION: THE ELUSIVE TEXT

The Merry Muses of Caledoniais, potentially, one of the most significant works which purports to be by Robert Burns. Equally, and particularly from the point of view of its editors, it is singularly challenging. The text of this new Luath edition is taken from the 1959 edition ofThe Merry Muses, published by Callum Macdonald in Edinburgh. It is accompanied by the original headnotes and essays from that edition, by James Barke, Sydney Goodsir Smith and J. DeLancey Ferguson. Smith’s glossary, which appeared in the 1964 American edition, with the same editors, is included. Three illustrations from the 1959 edition have been omitted: the title page of the first edition, ‘Ellibanks’ and an illustration by Rendell Wells of the Anchor Close, where the Crochallan Fencibles, early editors ofThe Merry Muses, met in Dawney Douglas’s tavern. This loss is more than compensated for by the inclusion of evocative new illustrations, drawn especially for the present edition, by Bob Dewar. For the first time, too, the music of the songs by Burns has been included: this fulfils the desire of the 1959 editors, thwarted by the untimely death of James Barke. In my Introduction, I seek to complement the work of Barke, Smith and Ferguson by discussing the development of their edition, and reviewing the peculiar history and characteristics of this elusive set of songs.

It could be argued thatThe Merry Museshas a life and a validity of its own, independent of any of its authors and editors. It is a conglomerate, and arguably amorphous, mass of songs. Although associated with Burns from an early stage in its life, it was first published after Burns’s death and without his approval. Neither is there any extant proof that he personally amassed these items, or composed them, with the intention to publish. Contrary to popular expectations, only certain of the texts, as the 1959 editors note, are verifiably Burns’s, or collected by Burns, because of their existence in manuscript, or publication elsewhere.

While some ofThe Merry Muses’contents are indisputably by the poet, or collected and amended by him, many more were bundled into 19th century editions by their editors, in an attempt to add weight through the association with Burns. It could even be said thatThe Merry Museshas a significance which is independent of Burns, revealing cultural expectations about bawdy song during its period of publication, from the late 18th century to, now, the early 21st. However, the mainfrissonattached toThe Merry Musesis, of course, its long association with Burns.

Previous editors have worked from the premise thatThe Merry Muses’s value is in rounding off the poet’s corpus, allowing readers to appreciate the full range of Burns’s output as songwriter and collector. The contents, too, are supposed to represent Burns as we hope he was: openly sexual, raucously humorous, playful yet empathetic to women. The existence of theMusespanders to the premise that Burns was the quintessential poet of love in all its forms, from the most sentimental to the most graphic. As Frederick L. Beaty noted in the 1960s, ‘to him sexual attraction was the most natural and inspiring justification for existence [...] from this basic premise [...] stemmed the related attitudes expressed throughout his poetry’.1Seen from that viewpoint,The Merry Musesoffers tantalising glimpses of Burns’s poetry at its rawest and bawdiest, at the extreme end of the spectrum of his love lyrics.

These are texts which require imaginative readjustments on the part of the 21st century reader, particularly for those who are unfamiliar with the bawdy or its modern erotic equivalents. At first glance, many of these songs seem odd, in ways which can range from the puerile to the mildly shocking. However, as Barke suggests in his essay, it is necessary to temporarily suspend preconceptions and enter into a worldview which, arguably, has persisted from the 18th century onwards, changing subtly along the way. Equally, it is essential to rid oneself of the ‘residual shame’ attached to erotica that Alan Bold identified inThe Sexual Dimension in Literature: ‘to judge from the evidence available, few people willingly admit to an enjoyment of erotic literature. They claim to read it for scholarly, for historical, for critical reasons but rarely for fun though in other areas it is accepted that entertainment can be combined with enlightenment’.2Burns, of course, was working within a rich and varied tradition of bawdry, in written and oral forms, in Scotland and beyond. At the more sophisticated end of the scale Dunbar comes to mind, like Chaucer in England and Boccaccio in Europe, for his knowing suggestions of women’s enjoyment of sex, in poems like ‘The Tua Mariit Wemen and the Wedo’. In terms of oral tradition, Scotland, as Barke indicates, has a rich and lively bawdry background, which is still extant. Bearing these factors, and Barke’s essay, in mind, it becomes possible to appreciate the songs, within their bawdy context, for their good humour, verbal playfulness, and disresp-ectfulness towards standard social mores.

THE CONTEXT OF BAWDRY

This was certainly the way in which they were enjoyed in the late 18th century. As DeLancey Ferguson explains in his essay, Burns circulated specific bawdy items in letters to trusted friends, like Provost Maxwell of Lochmaben, or by lending his now lost ‘collection’ to those he treated with self-conscious empathy, such as John McMurdo of Drunlanrig. These tantalising glimpses of his bawdy work, through references to it and the inclusion of selected pieces, suggest that Burns sought to flatter his friends by hinting at their gentlemanly broad-mindedness and their ability to enjoy without being corrupted. In this way, he could present himself as the poetic equal of the gentry by showing a common interest, sometimes expressed by the gentry through the possession of libertine literature and membership of erotic clubs. Burns was also indicating his own status as a gentlemanly collector, linked in a ‘cloaciniad’ way to his enthusiastic role in theScots Musical Museum.

It is in context of the ‘fraternal’ enjoyment of the bawdry, to quote Robert Crawford, thatThe Merry Musesmust be viewed.3It certainly represents the worldview of the 18th century drinking club. First published asThe Merry Muses of Caledonia: A Collection of Favourite Scots Songs, Ancient and Modern; Selected for use of the Crochallan Fencibles,4its apparent editors were a group of drinking and carousing companions. Its members included William Dunbar, one of its founders, and the presiding officer (also a member, like Burns, of the Canongate Kilwinning Lodge of Freemasons); Charles Hay, Lord Newton (the group’s ‘major and muster-master-general’) and Robert Cleghorn who was particularly involved with the ‘cloaciniad’ verses which interested the club. Burns refers to his membership of the group in writing, for instance, to Peter Hill, in February 1794, where he wishes to be remembered to his ‘old friend, Colon [sic] Dunbar of the Crochallan Fencibles’.5

Male clubs, ranging from those who shared intellectual ideas to those who shared more insalubrious experiences were, of course, common in Scotland at this period, as the 1959 editors mention here; several seem to have attitudes to sexuality which were active, imaginative and relatively unabashed. Burns himself had, as is well known, been part of the intellectually active ‘Tarbolton Bachelors’. The Crochallan group were, presumably, more sexually-orientated: they certainly enjoyed erotic and bawdy songs although they were, perhaps, less practically sexual than other, more colourful organisations such as the Beggar’s Benison — a club whose tastes ran to masturbatory rituals, and the detailed inspection of naked, very young women (Burns’s acquaintances included at least one member of the Benison, Sir John Whitefoord).6

Viewed from an 18th century gentlemanly perspective —although lessFanny Hilland more, as Barke puts it, ‘tap-room story’ — the songs become titillating rather than obscene, designed to elicit a chuckle (or, perhaps, a belly laugh). These are a relatively tame group of texts, playfully designed for consumption by a male audience. They are heterosexual in orientation, focussed on consensual sex in familiar positions, and with a strong focus on what used to be quaintly referred to as the male and female pudenda.7They operate according to their own rules — perhaps not as codified as those identified for other song forms, such as the ballad, but nevertheless apparent. They exhibit, too, most of the characteristics Bold identified in bawdy verse, in the introduction to hisThe Bawdy Beautiful:

They invariably utilise obvious hand-me-down rhymes, except when suggestive rhymes are implied. They rely on regular, thumping rhythms that crudely parallel the steady rhythm of the sexual act [...] [They] are thematically predictable — boy meets girl; boy is had by girl — so the structural bond of the verse need only be sound enough to carry the undemanding narrative.8

Another typical characteristic is the way in whichThe Merry Musesemploys easily-understood euphemisms for sexual experiences. ‘Nature’s richest joys’, for instance, are recalled in ‘To Alexander Findlater’. Then there is the statement in ‘Ye Hae Lien Wrang, Lassie’, based on farming experiences (like many of the metaphors here), ‘Ye’ve let the pounie o’er the dyke, / And he’s been in the corn, lassie’. This is hammered home, in case there was any misunderstanding (these pieces are not subtle), with an overt description of the symptoms of pregnancy, ‘For ay the brose ye sup at e’en / Ye bock them or the morn, lassie’. So, too, obvious images are used for the penis and vagina: the ‘chanter pipe’ which women play in ‘John Anderson My Jo’; the burrowing ‘Modiewark’; the ‘Nine Inch will please a Lady’ versus the women’s ‘dungeons deep’ in ‘Act Sederunt of the Session’ or ‘Love’sChannel’ (reminiscent of Cleland) in ‘I’ll tell you a Tale of a Wife’. Some, of course, are much more explicit, like ‘My Girl She’s Airy’, expressing appreciation for her ‘breath [...] as sweet as the blossoms in May’ and a longing, ‘For her a, b, e, d, and her c, u, n, t’.

The Merry Muses, at other times, is a self-conscious display of Burns’s ability in diverse poetic styles, within the context of bawdry. In ‘Act Sederunt of the Session’, for instance, he applies satirical techniques to suggest the ridiculousness of contemporary kirk attitudes to sex, suggesting a new law which makes sex compulsory. The punitive attitudes of the clergy to extra, or premarital, affairs are, similarly, soundly rejected in ‘The Fornicator’. Burns is — with humorous intention — engaging with the serious issue of contemporary church practices towards those who engaged in premarital sex which could range from the annoying and unpleasant to the inhumane.9Then there is the bawdy mock-pastoral of ‘Ode to Spring’.

Burns’s bawdry, too, reflects an interest in the oral traditions of erotica with which he was familiar and which, as Barke indicates, persisted and developed in Scotland in the 1950s, just as they do today. Burns’s interest in collecting bawdry, reflected here in pieces like ‘Brose an’ Butter’ and ‘Cumnock Psalms’, is part of his wider interest in traditional songs. In this he parallels other collectors with bawdy material (often unpublished in their lifetimes) within their wider collected repertoire, including David Herd and Peter Buchan. Burns collected, amended and composed bawdy songs in oral traditional styles. Examples here include the explicit, if rather mannered, voice of his collected ‘John Anderson My Jo’: no doubt an adapted and improved version of that in oral circulation in contemporary Scotland. As with much of his work, he reflects different aspects of sexuality, too: from the open enjoyment of sex, in many of these pieces, to a sympathetic awareness of its possible consequences for women, in ‘Ye hae Lien Wrang, Lassie’, humorously yet sensitively illustrated by Bob Dewar in this edition.

PERFORMANCE TEXTS

A major factor which has to be considered withThe Merry Musesis that it is, primarily, a collection of songs for performance, rather than designed to be read either silently, or aloud, as poems on the printed page. With the exception of one or two items, which are designed for recitation rather than singing, this is a collection which really comes to life when it is used as it was originally presented: ‘for use of the Crochallan Fencibles’, as a source text for singers. As Cedric Thorpe Davie said, considering Burns as a ‘writer of songs’: ‘but for the tunes, the words would never have come into existence, and it is absurd to regard the latter as poetry to be read or spoken aloud’.10This observation has particular validity forTheMerry Muses.

They have, of course, been recorded before, most successfully as a group on Ewan MacColl’sSongs from Robert Burns’s Merry Muses of Caledonia(1962), which owes an openly-acknowledged debt to the 1959 edition. This useful set of 24Merry Musesincludes scholarly and appreciative sleevenotes by Kenneth S. Goldstein, and certainly merits re-issue and wider distribution.11It features proclamatory and appropriate performances in MacColl’s distinctive style, which suitTheMerry Musesvery well. ‘The Jolly Gauger’, for instance, is performed in a pacy, assertive and thoughtful manner, slowing down slightly for the section where the girl is laid down ‘Amang the broom’, and with the verse where she lays ‘blessings’ on the gauger for his actions. ‘The Trogger’, equally, stresses the strong rhythmic qualities of the piece, with a drawn-out ‘trogger’ and ‘troggin’, enhancing the humour. MacColl shows an awareness, too, of the sophistication of other items. ‘The Bonniest Lass’, set here to ‘For a’ that, an’ a’ that’, starts in a gentle manner then shifts, appropriately, to a more aggressive — and sympathetic — performance style, building towards a venomous ending, speaking out against ‘canting stuff’.

More recently, Gill Bowman, Tich Frieret al’sRobert Burns — The Merry Muses(1996) have demonstrated that the songs still stand well as performance texts.12Notable interpretations include Davy Steele’s ‘Wad ye do that?’, which skilfully captures the wistfulness and appeal of the lover, as he pleads with the ‘Gudewife, when your gudeman’s frae hame’ to let him in to her bedchamber, as well as his intended’s couthiness of response: ‘He f—s me five times ilka night, / Wad ye do that?’. The deceptive softness of the tune, ‘John Anderson, My Jo’, is highly appropriate. Equally, Gill Bowman’s ‘How can I keep my Maidenhead’ shows an awareness of how the light tune, ‘The Birks o’ Abergeldie’, can adeptly underline the flirtatious opening, and underwrite the humour of the explicit ending. Other recordings worth mentioning include the driving version of ‘Brose an’ Butter’ onEddi Reader Sings the Songs of Robert Burns,13featuring Ian Carr, Phil Cunningham, Boo Hewardine and John McCusker in an engaging arrangemement. The farming-based euphemisms — the mouse and the ‘modewurck’ paralleled with ‘the thing / I had i’ my nieve yestreen’; the ‘Gar’ner lad’ desired ‘To gully awa wi’ his dibble’ — have humorous emphasis from the pacy performances.

Jean Redpath, too, included several ofThe Merry Museson her series of recordings with Serge Hovey.14‘The Fornicator’,15with a rapid and, at times, almost harsh accompaniment, and a drawn out ‘fornicator’, is an intelligent performance, using the rhythm of the tune self-consciously to add emphasis to the text. The pairing of a rather formal setting, with piano and flute, to ‘Nine Inch will Please a Lady’ is highly appropriate, with a pause before the first punchline, underlining the paradoxical pairing of the ‘lady’ and ‘koontrie c—t’ aspects of the piece, its humour underlined by Redpath’s characteristically polished traditional style.16

The comprehensive and groundbreaking Linn record series ofThe Complete Songs of Robert Burns, too, features several ofThe Merry Muses.17Janet Russell’s unaccompanied ‘O wha’ll mow me now’, for instance, emphasises the wryness of this woman’s reflections on her predicament, left pregnant by ‘A sodger wi’ his bandileers’. The cry of the refrain, ‘wha’ll m—w me now’, is genuinely regretful and deeply humorous. Russell’s knowing interpretation takes full account of its nuances. Ian Benzie’s intelligent version of ‘Green sleeves’ has a jaunty and yet urgent accompaniment which is well-suited to the words: Jonny Hardie on the fiddle emphasises the chorus line addressed to the true love: ‘I shall rouse her in the morn, / My fiddle and I thegither’ and Marc Duff, on bodhran, holds the whole together rhythmically. The bouzouki, played by Jamie McMenemy, and the recorder, from Duff again, add additional charm to this light-hearted song; it is cleverly paired, too, with a song with the less overtly erotic dialogue of love: ‘Sweet Tibbie Dunbar’.18

It is unsurprising thatThe Merry Musesshould receive such sophisticated treatments on the Linn series. Fred Freeman, its director, is acutely aware both of Burns’s musicality, and of the characteristics ofThe Merry Muses. In a recent discussion, for instance,19he drew my attention to the fact that the texts reflect 18th century notions of the grotesque, as a device for social satire, and as an antidote to, as Burns put it, ‘cant about decorum’. Freeman identifies, inThe Merry Muses, the ways in which Burns both ‘good naturedly airs these views’ with his intellectual peers and, simultaneously, ‘asserts himself, like a jolly beggar, before the upper classes’. Like Legman, Freeman sees these songs as expressing aspects of female experience —these are not, solely, pieces for male consumption:

In many of the songs the female is the superior sexual partner as she sooples the bestial male again and again: poking fun at his impotence (‘the laithron doup’ in ‘Come Rede Me Dames’ (‘Nine Inch will Please a Lady’) or deflating him, literally, in ‘The Reels of Bogie’). Then, too, she is so often the dispassionate observer — observing the male ‘fodgeling his arse’ in ‘Andrew an’ his cutty Gun’, or pronouncing boastfully ‘his ba’s’ll no be dry the day’ (‘Duncan Davidson’). She is his equal in the battle of the sexes (e.g., ‘As I lookit ower yon castle wa’, [‘Cumnock Psalms’]), and she can laugh at her own predicaments.20

As well as appreciating the playfulness, and wryness, of the texts, Freeman is acutely aware of Burns’s thoughtfulness in matching texts to tunes:

For Burns, the medium is the message. The tunes have everything to do with his idea of a unity of effect; everything to do with his intent. Practically speaking, this means that if his theme is purely playful or festive, normally with reference to dancing for joy, he will use a jig or slip jig. If he wishes to portray breathless excitement, as with the rising randy thoughts of his characters, or, indeed, of sexual action itself, he will use a reel, which is an unremitting, breathless form. If his poking fun has a level of pointed satire or jibe to it, he will use a strathspey, which is always punctuated with its Scots snaps.

Commenting in particular on the tunes (reproduced at the end of the present edition) of the 1959 editors’ A texts, Freeman is particularly impressed by the matching of words and tunes:

Not only are his tunes engaging and interesting in themselves but, again, he has adhered to his principle of a successful marriage of form and content: for example, breathless action or anticipation of action (reel – ‘The Fornicator’, ‘Ode to Spring’); poking fun at legislators (strathspey – ‘Act Sederunt’); high jinks, celebration (jig — ‘My Girl She’s Airy’ — ‘she dances, she glances’; ‘Nine Inch’ — joy of sex; ‘When Princes’ and ‘While Prose’ — sex as great happy leveller); (slip jig — ‘I’ll tell you a tale’ — as with ‘Brose an’ Butter’ which is also a mischievous tale); (Borders double hornpipe — ‘O Saw ye my Maggie’ — uses this [...] as archetypal characters of love, like ‘Wee Willie Gray’).

Freeman, equally, admires the use of ‘somewhat baroque’ tunes in pieces like ‘There Was Twa Wives’ and ‘Bonie Mary’, which allows Burns ‘to set his content into relief [...] as he implicitly thumbs his nose at propriety, upper class drawing rooms and polite conversation’.

Freeman, finally, sees strong parallels between the songs ofThe Merry Musesand those ofThe Jolly Beggars, as did Cedric Thorpe Davie. Davie notes thatThe Merry Musespairs texts and melody with skill, in the particular case of ‘I’ll Tell you a Tale of a Wife’ and the tune ‘Auld Sir Symon’; it does not distract: ‘the listener is not much concerned with the tune so long as he can fasten on the lewd lines’. This, says Davie, is a much weaker pairing when the same tune is used inThe Jolly Beggarsfor ‘Sir Wisdom’s a fool when he’s fou’.21The musical choices ofThe Merry Muses, then, as Freeman’s observations indicate, are often done with care, thoughtfulness, and with full knowledge of the relationships between text and air.

Other singers express their open appreciation ofThe Merry Muses, including Sheena Wellington.22When I asked her how the texts stand up in performance, she drew attention to the diversity of quality, and character, among the pieces; while some are ‘just your dirt dirty and that fair enough group’ others are ‘very clever’. Wellington particularly admires ‘Nine inch will Please a lady’ because ‘you can get a really good laugh out of that one’. Other pieces, according to Wellington, have ‘that thread o humanity that he couldnae help himself in doing’; examples include ‘Wha’ll Mow me Now’: ‘he obviously despises the lad that’s leaving this lassie’. Another particular favourite is ‘O saw ye my Maggie?’, for its pairing of words and tune.23Karine Polwart, equally, admires Burns’s songs inThe Merry Muses,24particularly for the ways in which they depict women: ‘he writes about them genuinely as real people, not as superficial, pretty objects, just of his desire. They’re kind of complicated people. Equally, like Freeman, and influenced by the experience of working on his Linn Records series, Polwart finds the way in which Burns used dance tunes, in particular, something of a ‘revelation’: ‘they’re great tunes [...] I think they’re absolutely fantastic language [...] and completely untranslatable [...] because the whole reason for the words is the rhythm and the sound and the percussive nature of the words, so you can’t just slot in another word [...] they’re amazing little songs’. Polwart particularly likes the songs which show women in ‘more stroppy moods’, like ‘O can ye Labour lee, young man’: ‘it’s basically a taunt, it’s a woman taunting a man about whether [...] he can really hold his own in the sack basically, that’s the whole point of it, and the dance songs were a good format for Burns to be cheeky, quite saucy, quite satirical, but quite pointed at the same time’.

The songs, as Polwart suggests, are of various types, with great diversity of tone and attitude. Many adopt, as Polwart suggests, and as Gershon Legman noted both inThe Horn Bookand hisThe Merry Muses, a perspective which is broadly sympathetic to women, if not quite female: these are women as men like to think they are: ready for, or thinking about, intercourse most of the time, as in ‘Ellibanks’, and measuring their men by their sexual prowess (passim). Their women certainly have a voice, if not much willpower: in ‘Let me in this Ae Night’, for instance, male persistence triumphs, although the women is allowed to express her regrets, humorously. Certainly, there is the implicit notion throughout that women deserve not to be abandoned when pregnant as in, again, ‘Ye Hae Lien Wrang’.

Ignoring or pruning this aspect of Burns’s work, as was routinely done in the 19th century, distorts the reader’s views of the poet. InBawdy Burns.The Christian Rebel, Cyril Pearl makes a strong case for defying the ‘effrontery’ of editors in ignoring, or even suppressing, Burns’s erotica. As an example, he cites the changes William Scott Douglas made in his published version of ‘Green Grow the Rashes O’, where he replaced, ‘A feather bed is no sae saft, / As the bosoms o’ the lasses’ for Burns’s original, ‘The lasses they hae wimple bores, / The widows they hae gashes O.’25Changes like these remove the smeddum of the original, and replace it with something both less potent and more pedestrian.

The Merry Muses, then, offers another facet to the construction of Burns’s poeticpersona, counterbalancing Henry Mackenzie’s fantasy (with which, of course, the poet willingly collaborated): the clean-cut, ‘heaven-taught ploughman’.26Equally, it could be argued that the work represents an attempt to present Burns as another fantasy creature, partly based in fact, and one which he actively fostered: the highly-sexed, unrepentantly bawdy, boozing — and, crucially, irresistible — womaniser. If Burns had not writtenTheMerry Muses, they would have to have been invented. This is where the book is problematic: there is a distinct probability that many items — particularly those of the late 19th and early 20th century editions — are neither by Burns nor were they familiar to him.

THE TEXTUAL HISTORY

The textual history ofThe Merry Musesis extremely complicated. Although many, or most, of its texts were no doubt familiar to the Crochallan members,The Merry Museswas not itself published as a book until three years after Burns’s death, in 1799, without being attributed to Burns in the book itself, and without his permission or approval. This volume has no specific reference to Burns and his precise involvement with its production would seem to be minimal if any. However,TheMerry Museswas linked to the poet through his association with the Crochallans.

According to a literary legend which was, as Ferguson notes here and discusses elsewhere, first recorded by Robert Chambers, the 1799 volume was compiled after Burns’s death, based on a manuscript allegedly inveigled out of the grieving Jean Armour.27This manuscript is no longer extant, or at least its location is unknown; in 1959 Ferguson revised his earlier opinion that it might have been destroyed. Related to the literary legend, the 1799 edition was long thought to have been published in Dumfries; modern scholars, including Ferguson, think it more likely that it was published in Edinburgh. Moreover, until the later 19th century, and not conclusively until the publication of the 1959 edition, the existence of the Crochallan volume was itself based on rumour. The one copy occasionally available to later 19th century editors, such as William Scott Douglas and, later, W.H. Ewing, was that which passed through the hands of William Craibe Angus and which, by 1959, was in the personal collection of the former Liberal Prime Minister, the Earl of Rosebery. The Rosebery copy, which is very slightly damaged, lacks a date, and so the only way of datingThe Merry Museswas to use the watermarks on its paper. These placed the volume at around 1800 or earlier. Ross Roy’s copy is dated 1799,28but, given the watermarking issue, it is still impossible even to date the book exactly. A microfilm copy of the Rosebery volume was made accessible to the 1959 editors, and is now available for consultation in the National Library of Scotland.29

It is possible, given Burns’s historical associations with erotica, that the manuscript alluded to, as discussed by Ferguson, or at least selected texts from it, was used by the Fencibles. Probably it had been seen by at least some of its most prominent members. However, it is equally likely that, if the Crochallans were indeed the authors (and, again, there is no absolute certainty), the songs were remembered from performances. This could be one explanation of why the texts by Burns intermingle with other items from the Club’s oral repertoire.

To complicate matters,The Merry Museshas been in constant flux and development since its first appearance. Even the 1799 edition, recently reprinted by the University of South Carolina Press, is based, in parts at least, on memories: the Burns manuscript that it is associated with has never been found although there are traces of it in various letters and references. Ferguson discusses this ably here in his ‘Sources and Texts of the Suppressed Poems’. Since 1799,The Merry Museshas passed through various incarnations; there were over 30 editions or printings, all with minor or major variations, up to 2000. There are concentrated clusters too: at least seven editions which can be tentatively dated between 1900 and 1911, and a minimum of 10 more, including a US printing, between 1962 and 1982. There is a gap between around 1843 and 1872 and, again, between 1930 and 1959, possibly reflecting attitudes to erotic texts, and censorship, at these times. It is recommended that readers with a particular interest in the textual history consult Gershon Legman’s 1965 edition ofThe Merry Muses, which includes a detailed bibliography.

THE 1959 EDITION

The decision I made to present the texts from the 1959 edition was taken for several reasons. First of all, the 1959 is an honest attempt to strip out extraneous texts which had been included alongside those of the 1799 edition. Barke, Smith and Ferguson’s endeavour was pioneering in that it was not caught up in the 1827 sequence (of which more presently), but drew directly on holograph texts where it was at all possible. The description of the texts as ‘The Merry Muses of Caledonia, edited by James Barke and Sydney Goodsir Smith, with a Prefatory note and some authentic Burns Texts contributed by J. DeLancey Ferguson’, is a far more accurate description than those in most of the 19th and 20th century editions, where the explicit attribution, ‘by Robert Burns’, usually appears.

The 1959 edition is valuable in that it groups the texts by their provenance: as songs in Burns’s holograph (by him or collected by him); songs from printed sources (by or attributed to Burns, or used by Burns for ‘polite versions’, many of which will be immediately familiar to readers) and those collected by Burns, as well as a final section of what they term ‘Alien Modes’, along with the related text of ‘The Libel Summons’. Smith explains this system fully, along with his reasons for excluding items from previous editions, in his ‘Merry MusesIntroductory’. Perhaps paradoxically, because the 1959 editors adopted such a rational system of presentation and organisation, and because they preferred holograph or verifiable texts to others, it could even be argued that Burns himself might have approved of this edition in a way which is unlikely with earlier issues of the work. The editors had good reasons, which they explain, to believe that these songs were collected, amended, or written by Burns himself. However, a cautionary note should be raised: even some of the texts indisputably by Burns were designed for private consumption among friends rather than for publication. This is not Burns as he might have wished to have been remembered or, in all cases, at his most polished. Finally, the 1959 edition was chosen rather than, for instance, the 1965 re-issue (which has minor changes from 1959), because it was the only version of their edition which Barke, Smith and Ferguson were all able to approve, although Barke, sadly, died before the final corrections of the proofs.

The 1959 edition was presented under the auspices of Sydney Goodsir Smith’s Auk Society, for which a subscription of two guineas bought a ‘free’ copy, anticipating the possibility of prosecution by publishing it openly for sale. This was, of course, still a real, or at least perceived, danger for erotic publications – even those of the relatively mild, heterosexual consensual type ofTheMerry Muses– prior to theLady Chatterleytrial of 1960, unsuccessfully prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959.30 High profile cases were within living memory of the editors. Examples included Radclyffe Hall’sThe Well of Loneliness, tried in 1928 over the fears it might encourage lesbianism, and the 1933 American trial ofUlysses— even if the latter was not judged to be pornographic. During the former trial, the Chief Magistrate insisted, ‘art and obscenity are not disassociated’31and this notion discouraged open publication ofTheMerry Museseven in the 1950s. There was, too, the long shadow cast by the ‘Hicklin judgement’ of 1868, which sought to determine ‘whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences’. No doubt all these factors caused the 1959 editors to err on the side of caution. A wish to anticipate being questioned along such lines lay behind the statement, too, ‘not for maids, ministers or striplings’, which is found on the title pages of most of the 19th century editions ofThe Merry Muses.

While attitudes to censorship have, of course, changed since 1959, and scholarship on Burns, too, has moved on immensely, it has to be said that criticism ofThe Merry Musesis still in its preliminary stages. Ferguson, Smith and Barke were among the first editors to consider the book seriously, as a collection which included significant work by, or recorded by, Burns. Their scholarly articles, drawing attention to the situations where the songs first appeared as well as to their contexts, particularly the comments in the headnotes, are extremely useful. Here, there is much more detailed commentary on the history of the texts than, say, the 1911 notes by M‘Naught, writing under the pseudonymn of ‘Vindex’ for the Burns Federation edition (of which more soon).

The discrete essays by each editor are also illuminating. Ferguson contributes an overview of the history of the various editions and, in particular of the holograph sources he argued were essential in establishing Burns’s authorship or at least that the pieces had passed through his hands, whether authored or collected. He makes modest claims for the edition, based on the admirable admission that so much is still unknown about its provenance. Barke’s piece, on ‘Pornography and Bawdry’ is a spirited discussion of erotic material, from the classroom to the barnyard, in early to mid 20th century Scotland, along with a humorous apologia for Burns’s forays into the genre: he puts Burns into context, both in terms of his contemporary bawdry climate, and also within the early 20th century, when several of the editions were published. Incidentally, Barke had researched this subject with care, as the Mitchell Library’s holdings show, collecting contemporary erotic broadsheets like ‘It Happened one Night’ and a euphemistic piece using metaphors around the radio (an ‘aerial erected’, for instance); his own localised version of ‘The Ball of Kirriemuir’, ‘The Ball of Borevaig’ (using chanter-pipe metaphors, reminiscent of ‘John Anderson, My Jo’), is quite imaginative.32Sydney Goodsir Smith completes the set of essays, with a scholarly discussion of the characteristics of each section. He stresses, too, the importance of making the texts available in a controlled environment, as here, based on the premise outlined above: ‘we cannot know Burns completely without them’.

While some ofThe Merry Musesappeared, often in expurgated forms, in editions of Burns’s complete poetry or works — most notably in the Aldine edition of 1893 and William Scott Douglas’s33– the 1959 editors worked primarily from selected key texts ofThe Merry Musesitself: the 1799 Rosebery edition and J.C. Ewing’s transcription of it in particular, as well as using the 1911 Burns Federation edition. I have chosen, therefore, to focus on them. The 1959 edition is, in the main, composed of items from the 1799 edition and, for the purposes of comparison, I would like to make some comments on the items they share in common. Incidentally, as this section is, inevitably, rather detailed and dry, the general reader may prefer to skip through the next part of the introduction and move straight on to the following essays.

THE 1799 EDITION

In total, 97 texts appear in the 1959 edition as compared to 86 in the 1799; of these texts, 76 feature in both volumes, although often with references to slightly different versions. These are indicated in the 1959 headnotes: where a holograph exists, the 1959 editors prefer it to the 1799 version. The 1959 choice of titles shows an intriguing difference with the original edition in that titles are often those of the chorus lines – in other words, the ones the audience would join in on – while the 1959 editors prefer more literary titles. Perhaps this indicates a greater respect for the whole, by the 1799 editors, as performance texts. The 1959 scholars arguably, being more used to dealing with words, treat the texts more as fixed on the page, than as musical possibilities. Barke as a piper, of course, was the exception, but sadly his untimely death meant he had no opportunity to apply that knowledge to the songs.