12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

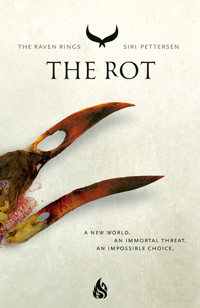

- Herausgeber: Arctis US

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: The Raven Rings

- Sprache: Englisch

I loved (Odin's Child) deeply from the first to the last word, and was instantly and thoroughly immersed. -- Laini Taylor, bestselling author of Daughter of Smoke and Bone. ...The story examines and upends everything its characters believe in, including their world, their history, their faith, and themselves, while intertwining elements of politics and Norse mythology with a side of forbidden romance. Kirkus Reviews Blood magic, blackmail, and battle rock a rich world of fading magic to its core in this internationally bestselling Norwegian epic fantasy. Publishers Weekly The intrigue, scope, and depth of His Dark Materials, set in an immersive Nordic world as fierce and unforgettable as its characters. Rosaria Munda, author Fireborne/Flamefall - Aurelian Cycle The world building is stupendous. MidWest Book Review HIrka has been sent to the world of the blind, a powerful and immortal people whom she has been taught to fear since infancy--and who now see her as their only chance to reignite a thousand-year-old war. The blind will use Hirka's ability to travel between worlds to return to Ym, the land where Hirka grew up and where the blind were betrayed all those years ago. And this time, they will prevail. Hirka is torn between her loyalties to the people who birthed her and the people who raised her, between the savior she is expected to be and the individual she wants to be. And every choice she makes pulls her further away from Rime, the love of her life, who is doing everything he can to stop Ym from falling to pieces all around him. A million things stand between Hirka and Rime. But only together can they stop the end of the worlds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 684

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Siri Pettersen

The Raven Rings

The Might

Translated by Siân Mackie and Paul Russell Garrett

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are from the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA, Norwegian Literature Abroad.

W1-Media, Inc.

Imprint Arctis

Stamford, CT, USA

Copyright © 2022 by W1-Media, Inc. for this edition.

Text copyright © 2015 by Siri Pettersen by Agreement with Grand Agency

Evna first published in Norway by Gyldendal, 2015

First English-language edition published by W1-Media, Inc./Arctis, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

Author website at www.siripettersen.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021944679

English translation copyright © by Siân Mackie and Paul Russell Garrett, 2021

Cover design copyright © Siri Pettersen

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

ISBN978-1-64690-602-4

www.arctis-books.com

To all those writing their first novels.

And to you. The one who has suffered loss. The one with so many scars that you feel ill when others say you’re lucky. The one who has been broken into far too many pieces to believe you’ll ever be whole again. The one who thinks you’ll never rise again. This is your book.

BACK FROM SLOKNA

Rime bounded up the slope, confident that no one could see him in the dark. He reached the crest of the hill, pressed himself up against a crag, and looked out across the countryside. Where he should have seen a deserted landscape, there was instead a vast camp, with tents arranged in tidy rows. In patterns that were only found where discipline was the order of the day. Where someone was in charge.

An army.

It was too dark to see how far it stretched. A couple of thousand men, maybe, judging by the torches. He could see tracks in the snow—a black web connecting the tents. Men gathered around a fire below him. They moved with a spring in their step and laughed boisterously. Rime recognized the atmosphere. First or second night, if he were to guess. It wouldn’t be long before they’d be hunched over in silence. Those who hadn’t frozen to death or fallen ill.

The banners hung limply, but he knew they bore the sign of the Seer. Mannfalla’s army, gathered outside the city. Why? What were they waiting for? What orders had they been given, and by whom?

She was right.

Damayanti had told him he’d find them here. She’d also told him it had to do with him. And with Ravnhov. But with Urd gone, she was no long privy to Council matters. The dancer’s guesses were no better than his own.

It could be an exercise, of course. Troop movements. Or unrest in the wake of the war …

Tenuous explanations like those did little to settle the unease gnawing at his insides. A feeling that nothing was the way it should be.

Maybe it was the raven rings. Was it at all possible to move between worlds without the ground slipping out from under you? Some instability was to be expected.

But this was more than just a feeling. It was a certainty that stopped him from going straight home. He’d barely been gone twenty days, and in that time, someone had dragged the soldiers out of bed again. The watch on the city walls had been reinforced, and several of the guardsmen had been swapped out for men he didn’t recognize.

Something was wrong.

He had to talk to Jarladin.

Rime ran back down toward the city. Packed snow creaked under his feet. He neared the city wall and proceeded with more caution, crouching down behind a cluster of junipers. Four guardsmen patrolled above the gate. Otherwise, long stretches of the stone wall, a gray-speckled serpent in the darkness, remained unguarded. He found his way back to where he’d climbed over. A part of the wall where he couldn’t be seen from the gates.

Rime removed his gloves and shook the snow off them before stuffing them in the pocket of his bag. Then he bound the Might and started to climb. The rough stones gave him just enough purchase to reach the top of the wall. He pulled himself over the edge, crossed to the other side, and lowered himself onto the roof of a building. A tile came loose and skittered down toward the gutter. He threw himself after it, catching it just before it went over.

With the roof tile safely in hand, he sat and listened. A door slammed in the distance. There was a rustling in the alley below. A rat with its teeth sunk into a dead pigeon, trying to drag it across frozen leaves.

Rime wedged the tile back into place and continued across the rooftops toward the wall that separated Eisvaldr from the rest of Mannfalla. The buildings were close enough together that he could make it all the way there before he had to return to street level.

The wall itself wasn’t much of an obstacle. People had always passed freely between Mannfalla and Eisvaldr. Even so, the watch had been increased here as well. Guardsmen flanked all the archways. A sign clearer than any road marking. Fear had taken over.

Rime slipped into an alley behind an inn. Singing reached him through an open window. Half-drunken verses, but even the notes were cleaner on this side of the city. He took off his bag and strapped his swords to the middle of it, so they wouldn’t stick up over his shoulders like an open declaration of war. He pulled his hood all the way down and crossed the square. The guardsmen gave him a cursory glance but let him enter Eisvaldr unchallenged.

His city. The Council’s city. The Seer’s city.

The Seer he had killed.

The memories flooded back. Naiell, hissing in the corner like a cat. The resistance Rime’s sword had met when it sliced through his body. The spatters of blood across Hirka’s bare feet. The look in her eyes. Brimming with grief. With betrayal.

I am what I am.

Rime glanced up at the stone circle, where it stood feigning innocence, like the tip of an iceberg. The stones reached all the way down to a cave below Mannfalla. A cave he’d just come from, unbeknownst to anyone.

Here on the surface, the stones were just pale monoliths against the dark sky, at the top of the steps where the Rite Hall had once stood. Where he himself had stood. In the middle of the circle, surrounded by everyone in the city. With Svarteld bleeding out on the ground in front of him. And for what?

Rime lowered his head and kept walking. He’d wasted enough time on loss and regret. More than he cared to think about. Now it was time to find out what had happened while he’d been gone.

Jarladin’s house was at the top of the hill, one of many in a well-kept row of homes belonging to Council families. Rime slipped past some bare fruit trees, keeping to the paths to avoid leaving tracks in the snow. He had to remain unseen, at least until he knew for certain what was happening. He scaled the stone wall at the back of the house. It was late, but he could see light flickering in a window on the second floor.

It was a magnificent house in the Andrakar style, complete with columns and carvings in dark wood. Climbing it would be child’s play.

Rime pulled himself up onto a pitched roof and crept along a ledge to the window. He pressed his hand against the glass, melting the frost so he could see inside.

Jarladin was alone in the room, seated on an upholstered stool, staring into the fireplace as though waiting for the flames to die out for the evening. He was turning an empty glass in his hands. His broad shoulders were hunched. Rime was painfully aware that he was part of what was weighing on the councillor. He’d disappeared. Without warning or explanation.

He fought off the urge to climb down again. To stay disappeared. A black shadow in the winter’s night. When had he ever belonged inside in the warmth?

Do what has to be done.

Rime glanced back to make sure he was alone. Then he tapped the window three times. Jarladin gave a start. Dropped the glass on the floor, though it didn’t break. He stared at the window. Then approached, squinting, with his shoulders hunched up by his ears. Then came the recognition. Wide-eyed disbelief. He started to fumble with the hasps.

Rime shifted over so he was on the right side. Jarladin opened the window and grabbed Rime as if he were about to fall. Pulled him inside. Drew him close. Locked him in a bear hug. Drowning him in warmth.

The councillor pushed him back again, holding him at arm’s length as he looked him up and down. He cradled Rime’s head in his hand. Grabbed him by the hair, as if he was going to pull it. His eyes were shining. Rime braced himself, fully aware that the warmth would be short-lived. The change was already visible on Jarladin’s face. Rueful joy gave way to confusion.

“Where have you been?” he murmured.

Rime pulled away without answering, going to shut the window.

“Where have you been?!” Jarladin’s voice cracked, as if anticipating the pain to come.

Rime glanced at a chair by the fire. Wished he could sink into it. Rest. Slip into dreamless sleep. Instead, he had to answer for what he’d done. Try to explain the inexplicable.

“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you,” he said.

“Where have you been, Rime An-Elderin?” Smoldering anger now. A silent threat hanging between them. He needed an explanation, and it needed to be good. Jarladin had probably thought he was dead, but his reaction revealed a deeper desperation.

Rime forced himself to ask. “What’s happened?”

“What’s happened?” Jarladin repeated the words as if they were the epitome of stupidity. “What’s happened?! You killed your own master in a duel, then disappeared! That’s what happened! All of Mannfalla was there, and you haven’t been seen since. I thought Slokna had taken you, Rime! That Darkdaggar had finally killed you. I thought …”

Rime looked away, trying to avoid Jarladin’s gaze. But it was no use because the councillor was staring at him from the wall. Him and the rest of his family, framed in gold. No matter where Rime looked, there were eyes on him. He was a cold stranger in a warm room. A room that reminded him of Ravnhov, with a stone fireplace and wooden rafters. Cozy, but not for the likes of him.

“And the others? What did they think?”

Jarladin flung his arms out in exasperation. “What do you think they thought? The theories are getting wilder and wilder. Kolkagga killed you to avenge Svarteld, Ravnhov burned you alive, you drowned yourself in the Ora, or even better: the Council finished you off themselves. That was a popular one in the taverns, as if we didn’t have enough problems! Rime An-Elderin vanishes following accusation of assassination and resulting duel. Your absence has poisoned us. What did you expect?! You were the Ravenbearer!”

Jarladin grabbed another glass from a tray on the table. He went to fill it, but the bottle was empty. Not a single drop came out. His knuckles grew white around the neck of the bottle.

“The dogs went for each other’s throats. Each family grew suspicious of all the others, naturally. The corridors reek of past injustice. So now they’re forming alliances. Hiring guardsmen. Building up their private forces, thinking they’re doing it in secret, but any idiot can see that money is pouring out of Mannfalla. Out into the regions. All of Ym can see that the Council is falling apart. Before long we’ll see kingdoms pitted against kingdoms. That’s what happened, boy! Thanks for asking!”

Rime sat down on the stool. Dragged a hand over his face.

So that was why there were soldiers waiting outside the city gate. They were moving out into the regions. As gifts. To build alliances. Buy loyalty …

A bad sign, but nothing that couldn’t be fixed. There was still hope. Still empty seats on the Council. Urd’s. Darkdaggar’s. Surely those could be used to bring stability.

“Has anyone laid claim to Darkdaggar’s seat?”

Jarladin sputtered out a laugh. The truth cut like a scar across his face.

Rime got up, feeling a chill seep into his skin. “He still has it?”

The question hung in the air unanswered. Rime raised his voice. “He tried to have me killed, and he’s still on the Council?”

“You weren’t here!” Jarladin seethed. “You weren’t here to sentence him. Darkdaggar claimed his confession was made under duress. He said you entered his family home. Uninvited. Threatened him. He had nothing to lose, Rime. Nothing. So he struck all the usual chords. Blamed Ravnhov. After all, that’s where the assassination was attempted. And the Council believed him. Acted as if they believed him. Because they wanted to believe! Because they needed him. And because as far as they’re concerned, you’ve been a walking disaster ever since you became Ravenbearer. If they’d held out any hope of success, most of the councillors would have done away with you personally. So yes, Darkdaggar still has his seat. Had you only let the assassin live, we’d have a witness, if nothing else.”

Rime slumped back against the wall and shut his eyes. Laughed bitterly. “You sound like her. Live and let live, right? Do you really think Darkdaggar would have let him testify? The man was dead the moment he accepted the job!”

Anger is costly. Focus on what you can change.

For a moment he thought they were Svarteld’s words, but it was something Ilume had said. His grandmother. A whisper from Slokna. A pointed reminder of his failure to master politics.

He looked at Jarladin. The bearded ox. The fire cast a red glow across half his face. The other half lay in shadow, as if he had one foot in Slokna.

“I’m here now,” Rime said. “The damage can be undone. There are plenty of options. We could—”

“Rime … The Council had one wish, and that was to be rid of you. You took care of that all on your own. It’s over. They’ll never take you back. Eir bears the staff again. I thought the augurs and the people would protest, but not so much as a stone has been thrown. They’ve heard that you promised a seat to Ravnhov. They’ve heard that the chieftain killed you for failing to honor your promise. Darkdaggar has done a great job of tarnishing your reputation. You lost your mind. You killed an innocent boy in Reikavik.”

The words cut deep, opening a well of painful memories. The village by the river. They’d thought it was nábyrn. Deadborn. But all they’d found was a wounded bear in a cellar. The child … His frail body, resting against the wall. Red hair. Dead eyes. He remembered the man who’d killed the boy. Kneeling before him. And he remembered the taste of his own rage. Still he’d hesitated. Svarteld had had to finish what he had started. Svarteld, who had sacrificed his own life to teach him to finish what he started.

Rime took hold of Jarladin’s arm. “You know what happened, Jarladin! I’ve never … I would never …”

Rime met his gaze and understood.

It didn’t matter whether he’d killed the boy. Svarteld had been the only one in the house with him, and he wasn’t around to testify anymore, either.

Rime sank back down onto the stool. He’d forgotten his words to Hirka, words spoken what seemed like an eternity ago. That unless it was useful to them, the Council had no interest in the truth.

Jarladin came over to him. Towered over him like the ox he was.

“So tell me, Rime … Where have you been?”

Rime felt leaden. Dragged down into a mire of death. Of injustice. His thoughts were murky. As if he’d been drinking. As if nothing was real anymore.

Somewhere deep down, he knew he’d accomplished something. Something important, something worth all of this. It would sound like madness, but it was a story that had to be told.

“I followed her,” he started. “To the human world. I found deadborn brothers as old as the Might itself. Nábyrn who still remember the war. One of them is her father. She’s half blindling, Jarladin. Half menskr, half deadborn. Daughter of an exiled warlord. And I found him. The Seer …”

Jarladin rubbed his chin. A telling gesture. Rime knew what he was thinking. That the Council was right. That Rime An-Elderin, grandson of Ilume, had lost his mind. Tipped over the edge. Gone mad.

Rime looked up at him. “He was real, Jarladin. The Seer was real.”

Jarladin folded his arms across his chest. “So what did you do when you met him?”

Rime felt his body go numb. “I killed him.”

“You found the Seer, and you killed him?”

Rime nodded. Stared into the fireplace. The flames had gone out. Red embers danced across the charred wood. He should feel something more than just emptiness.

“So you conquered your demon. You followed her to Seer-knows-where, and now you come back here thinking the world stood still. That your actions didn’t have consequences. As if the rest of us don’t have our own demons.”

Rime stood up. “You think I’m imagining—”

Jarladin jabbed a finger at him. “I did everything in my power to protect you! EVERYTHING! You had one friend at the table, and you vanished! Without so much as a word! I defended you. I …” He stopped himself. Cocked his head. Stared with growing disbelief. His eyes searching for something Rime knew they wouldn’t find. His tail.

Explanations were useless now. A chasm had opened up between them. The sides were too steep, and he wouldn’t be able to surmount them. Not tonight.

DREYSÍL

From darkness to light.

Blinding white. Snow.

Flurries of white whipped past her. Sideways. Or was she falling?

Hirka leaned against the rock wall. Stone. Snow. She was through.

She fought back the nausea. Took a deep breath. It tore at her lungs. Cold. So cold. Something creaked.

She looked down at the metal box in her hands. Frost was spreading across its surface, forming roses around her fingers. She tucked the box under her arm and pulled her sleeves down over her hands.

Where am I?

The dizziness abated and she straightened up. What she’d thought was a rock wall was actually one of the stones in the ring she had just come through. The sheer size of it had been misleading. The stones towered over her. Reaching up toward … a ceiling?

Using her hand to shield her eyes from the light, Hirka peered up at the broken ceiling. Sharp sections jutted toward the clouds. She was in a hall. Or the ruins of what had once been a hall. Bigger than anything she’d ever seen before. Ice had forced its way inside and hung from archways on multiple levels. The wind blew through big gaps in the walls. And she was up to her knees in snow. Inside and outside at the same time.

A movement drew her eye. A man. He was running toward her. She could hear the sound of his shoes breaking through the frozen crust of the snow. Someone shouted after him. A voice that cut through the wind.

“Keskolail!”

The man kept running and didn’t look back. He was close now. White eyes wild. A deadborn. Hirka dropped the box and groped for the knife on her hip, but it wasn’t there. Fear gripped her.

Your boot! It’s in your boot!

She wouldn’t be able to draw it in time. But no sooner had the thought crossed her mind than she realized that the man hadn’t even seen her. His eyes were locked on some point behind her. Between the stones. That was where he was headed.

A bowstring sang. Hirka opened her mouth to warn him, but it was already too late. The arrow thudded into his back. He stiffened. His legs gave out and he dropped to his knees in front of her. She reached out to him, wanting to help, but her feet were stuck in the snow. She couldn’t get free.

He stared at her, white eyes mesmerizing. The wildness was gone. Death was a certainty that seemed to astonish him. He raised his hand and clawed at a teardrop-shaped mark on his forehead. His lips pulled into a grimace, revealing his canines. Then he toppled forward and lay with his face buried in the snow. A black arrow, short and sturdy, had pierced his shirt and was sticking out of his back. It seemed absurd that something so small could fell such a creature.

Death. In a world she’d never seen before. A world she doubted any ymling or human had seen. And death was the first thing she had encountered. What had he done wrong?

And me? Have I done anything wrong?

Was she a target as well? Hirka finally managed to free herself from the snow and looked behind her. The stones were dead. It was too late to turn back.

Four figures were approaching now. Three of them stopped a short distance away. The fourth headed straight for her. A woman. Was she the one who had shouted?

She walked with the utmost self-assuredness. As if no one would ever be able to touch her. A cloak fluttered behind her, so weightless that it seemed to be more for decoration than warmth. Leather straps were pulled tight around her waist. Her boots came up to her knees. But her thighs and arms were bare.

Hirka shivered. She pulled her own cloak tighter. What had she expected? That they’d dress like Graal did in the human world? Or walk around naked, like the ones she’d seen in Ym? She didn’t know. Didn’t know what she’d expected.

She picked up the box she’d dropped in the snow.

The woman stopped in front of her, hands on hips. Her lips were black. Her hair, too. A mass of long braids, in stark contrast with her pale face.

Hirka took an involuntary step back and looked up into milky white deadborn eyes, as difficult to read as those of all the other blindlings she had encountered.

Umpiri. They’re Umpiri, and you’re one of them.

The woman cocked her head, leaning toward Hirka like she was about to sink her teeth into her neck. Hirka didn’t dare move. The deadborn breathed in through her nose as if scenting her. It was distinctly animalistic. Hirka held her breath. Glanced at the dead man in the snow. She couldn’t help but feel like she was about to suffer the same fate. Like she was at the mercy of a wild animal. Naiell had been animalistic as well, but not like this. Maybe both he and Graal had been influenced by their time among ymlings and humans.

She’s a friend! Graal promised I’d be met by a friend.

The woman straightened up again. Hirka thought she saw pain flash across her features, but she must have imagined it. Pain seemed too foreign to this creature.

“So it’s true …” the woman said in broken ymish.

Remembering that the blind could smell their own, Hirka could only assume that she was referring to her being half blindling, but she didn’t ask for clarification. She had the overwhelming impression that she wasn’t welcome.

“I am Skerri of the House of Modrasme.”

“Hirka.”

“Hirka? That’s how you introduce yourself?” Her displeasure was unmistakable.

Hirka nodded.

“Not anymore. Now you are Hirka, daughter of Graal, son of Raun of the House of Modrasme. And you have much to learn.” Skerri nodded at the box. “Is that … ?”

Hirka nodded again. Finally she saw the shadow of a smile on Skerri’s face. A quirk of her black lips. Naiell’s heart in a box. Was that what it took to please her? Hirka shuddered.

Skerri glanced at the other three. “Keskolail!”

Hirka recognized the word from moments before. One of the three men came toward them, and Hirka realized it was probably his name. Meaning he’d been the one who’d loosed the arrow at Skerri’s command. Why?

Keskolail was a large man and wore considerably more clothing—a black jacket with a shaggy sheepskin slung around his shoulders. He was carrying a bow. His hair was gray as steel, but he couldn’t have been more than forty years old. That said, he was Umpiri. He could have been thousands of years old, for all Hirka knew.

He had the same mark on his forehead as the dead man. A gray teardrop. He turned his head and Hirka saw that it wasn’t drawn on. It went deeper than that. Like a dull gemstone. He crouched down and pulled the arrow out of the man’s back. There was a sound like something breaking. Blood dripped from the tip and into the snow. Hirka stared at him, but he paid her no heed, not so much as glancing at her or Skerri.

He wiped the tip of the arrow in a fistful of snow before shoving it into a sleeve hanging from his belt. Then he gripped the dead man by the neck and dragged him outside, through one of the holes in the wall.

Hirka couldn’t shake the feeling of powerlessness. What had she gotten herself into? She looked at Skerri. Her skin was pale as the sky above, making the black all the more stark and threatening. Her hair. Her lips. The leather. She was black and white. Nothing in between. She was the only deadborn woman that Hirka had ever seen, and the most terrifying of them all. Hirka clung to the certainty that Graal needed her. He wouldn’t have sent her to her death.

“He wasn’t after you,” Skerri said, her eyes following the macabre trail left by the dead man.

“What was he after?”

“The Might,” she replied, as if it were obvious. She turned suddenly, her black braids whipping across her back, weighed down by beads at the ends. She walked toward the two others, who stood waiting.

Hirka looked back, but Ym was gone. All she’d seen of it was a dark cave beneath Mannfalla, where the stones plunged through from above. And Damayanti. The merciless dancer had sent her onward without so much as a glimpse of the world above. She hadn’t seen the city. Hadn’t visited Lindri. She had a promise to keep, and she belonged here now.

Where is here?

Hirka followed Skerri, more out of necessity than desire. “Where are we?”

“This is Nifel, the broken city. We’re not staying here.”

Hirka resisted the temptation to ask what had felled it. “But … the world? What do you call—”

“Dreysíl. The first land.”

“Oh …” Hirka shifted her bag into a better position. Snow had been blown into the hall and formed drifts. The walls had collapsed at one end. Broken columns stuck up like bones out of the snow. The two men were waiting by one of them. Skerri signaled something to them and they exited the hall before Hirka even had a chance to say hello. All she had time to notice was that one of them was as lightly dressed as Skerri. Undaunted by the elements.

“Where are we going?”

“Ginnungad,” Skerri replied without turning.

“Is it far?” Hirka could feel the cold gnawing its way into her bones. She looked around, hoping to spot a cart and horses, but all she could see was snow. “Don’t you have horses?”

“For what?”

Hirka almost got stuck in the snow again.

“For riding.” Maybe it was a language thing? Skerri’s ymish did seem a little shaky. It was as if she were speaking it against her will. But she stopped. Turned to look at Hirka and bared her canines. “Do I look like I need to be carried?”

Hirka shook her head. “I didn’t mean—”

“Four days. Ginnungad is four days away.” Skerri looked Hirka up and down. From top to toe. The disappointment was clear, even in her blindling eyes. “Let’s say six days,” she sneered, before walking on.

REFUGE

Rime crept across the rooftop until he reached the edge. There he stopped. Listened. The creaking of the ice along the riverbank. Someone emptying a washtub out a window a couple of houses along. He waited for a moment. Had to be careful. Coming here could put Lindri’s life in danger.

The teahouse had become something of a refuge. A safe haven in no-man’s-land. Lindri’s door was always open, and Rime had nowhere else to go. Not without rumors spreading through Mannfalla, and he couldn’t let that happen. Not until he had a plan.

The wind had picked up. Rime rubbed his hands together, trying to force some life into his frozen fingers. After twenty-four hours in this cold, even the Might had given up keeping him warm.

He grabbed hold of the edge, rolled forward, and dropped down onto the platform at the rear of the teahouse that served as a jetty of sorts. There was a rocking chair and an ice-covered lantern by the wall. A creeper had climbed as far as the eaves but then withered in the wintry cold.

He could see a sliver of light in the gap between the door and the frame. Rime knocked. It was quiet for a long time, then the door opened a crack and an eye peered out at him.

“It’s me,” Rime whispered.

Lindri recoiled as if he’d been burned. The door creaked open. A candle fell from his hand and went out as it rolled across the platform. Rime stopped it with his foot. The tea merchant let out a gasp and made the sign of the Seer, backing away.

Rime seized him by the arm. “No, no, I’m not dead, Lindri! Do you hear me? I’m not dead.”

The look of terror faded, and he bundled Rime inside. He poked his head out and looked around before shutting the door. Like he was expecting others or simply couldn’t fathom how Rime had gotten there.

The back room was cramped. Full of boxes and burlap sacks. The air was thick with hay dust, triggering a sudden memory. Rime had stood here with Svarteld the night Kolkagga had rowed out to Reikavik. They’d argued about things that now seemed trivial. What was it he’d said?

You can’t govern the world from Slokna, boy.

Lindri ushered him farther into the teahouse. The tables and benches appeared gray in the darkness, the gleam of the wood stolen by the night.

“Sit, sit,” Lindri said, pushing him firmly but gently onto a bench by the hearth. The fire had gone out, but some of its warmth remained. Just enough for Rime to realize how cold he was.

Lindri prodded the charred wood with the poker.

“Leave it, Lindri. No fire. Nobody can know I’m here.”

Lindri rummaged through the wood pile. He tore off a strip of wood and started to build up the fire like he hadn’t heard a word. Rime wanted to explain. Wanted to warn him that having him there was not without danger, but he knew Lindri wouldn’t listen. The wrinkly old tea merchant had taken Hirka in without a thought for his own safety. Even after finding out she was menskr. Empty tables were the price he’d paid.

He’d taken Rime in before, too. When he was still the Ravenbearer. When Damayanti had given him the beak. And now, as a disgraced son of the Council. Presumed dead.

The fire crackled to life, casting a warm glow over Lindri as he crouched in front of the flames. Rime suddenly noticed he was in his nightshirt. And a cardigan that was fraying at the wrists.

Lindri clambered to his feet with obvious discomfort. He sat down across from Rime. His eyes were crinkled with age, making them small and round. He rested his hand on Rime’s, warmth burning through a layer of loneliness.

Rime swallowed. “So you don’t believe them? What they’re saying about me?”

“Tell me what happened first and then I’ll tell you what I believe,” Lindri answered with a mesmerizing calm.

Rime chuckled, and then the floodgates opened. Words started pouring out of him, though he knew none of it would make any sense. He couldn’t stop. For the first time in his life, he felt like he was sharing something real. He told Lindri about his visit to the human world. About the brothers, Graal and Naiell. About their thousand-year rivalry. One exiled, the other the Seer himself. The Seer that Rime had killed.

The lie he had been fed his entire life no longer existed. Instead he’d uncovered the story of the blindling who had betrayed his own people and conquered all of Ym.

He told Lindri about Hirka, about her blood. That she was one of them. Those who wanted to break through the gateways and enter Ym in order to reclaim what they had lost long ago. And there was nothing Rime could do to stop them. Not anymore. Not now that he’d thrown away what little power he’d had.

Words and strength failed him. He knotted his hands together and rested his chin on them. He looked at Lindri, waiting for a reaction to everything he’d said. But none came. Lindri sat nodding to himself, even though Rime had stopped talking. His eyelids were so heavy that for a moment Rime thought he’d nodded off. But then he straightened up and slapped his thighs.

“So the world is going to end? Is that what you’re saying?”

“That about sums it up,” Rime replied.

“Well, then there’s only one thing to be done.” Lindri rose slowly to his feet. The wrinkles on his face cut deeper, betraying the pain in his bones.

“What’s that?” Rime asked.

“Make tea.”

Lindri went over to the counter and lit a burner under one of the black cast-iron pots. They were all lined up with their spouts facing the same direction.

“Make tea? That’s your answer to the world ending?”

“Do you have a better suggestion?”

Rime stared at the table. Its surface was rough as driftwood. Covered in nicks and scratches.

No, he didn’t have a better suggestion. The storm would come no matter what he did.

Lindri set the pot down in front of him. A rich scent rose up. It smelled suspiciously strong for tea. He sat back down and pushed a full cup toward Rime.

“So you killed the Seer? Her father’s brother?”

“He would have killed her, the moment he got the chance.”

Rime felt the outline of the shell in his pocket. The pendant he’d given her when she’d left Ym. Now it was his again. Returned to him by Graal. With no explanation. Was it his way of saying that he should forget about her? That she was half blindling, destined for an altogether different fate than Rime?

He hoped so, because the alternative was far worse. That Hirka had asked Graal to give it to him. That it had been what she wanted.

His chest constricted. He grabbed the cup and downed it in one. It was blessedly strong, burning all the way down.

He hadn’t realized how much he wanted her until they’d met in the room with the pounding music. Packed full of menskr. Children of Odin everywhere he looked. But he might as well have been alone with her because everything and everyone around them was forgotten.

He would have taken her then and there if he’d had the chance. The feeling was that powerful, that all-consuming.

That destructive.

He’d done crazy things because of her. Things that had not only destroyed him, but now threatened to destroy the Council. Ravnhov. Ym.

He’d taken the beak. Made himself a slave. Something he’d neglected to tell Jarladin and Lindri. Nobody could know how powerless he actually was. That he was at the mercy of Graal’s whims.

Graal was more dangerous than Hirka realized. He would pit them against each other if he had to. They could only hope that Graal loved her, too. Rime had seen a father’s pride in his eyes. But also an absolute willingness to step over bodies.

That’s what she says about me.

“I know what you are and what you’re not, Ravenbearer.” Lindri refilled his cup. It was as if he’d read his mind.

“I’m not the Ravenbearer anymore, Lindri. As far as anyone knows, I’m dead.”

“If I may, Rime An-Elderin … You’ve told me what happened, and now I’m going to tell you what I think. I grew up in this city, and I remember the day you were born. It wasn’t that long ago.”

“It was almost twenty years ago, Lindri.”

Lindri smiled, his crow’s feet reaching his temples. “The child everyone waited for. The child the Seer said would live. I remember thinking it wouldn’t be much of a life for a boy. Growing up under so much pressure. They were selling amulets with your likeness that same day. Did you know that?”

Rime was all too aware. He worried at a chip in the teacup with his fingernail. There was something familiar about it. He must have drunk from the same cup before. He took another sip. The smell stung his nostrils.

“The way I see it, Rime, you’ve grown up in a cage. A cage the rest of the world envies, but a cage nonetheless. Everything was set for you to become one of them. But they didn’t count on you growing strong enough to choose your own path. I don’t agree with everything you’ve done, but there’s no denying your iron will.”

The wind howled outside. Lindri started rubbing his wrists, as if the sound had reminded him how cold it was. He continued talking.

“They’ve been saying all sorts about you. Personally, I thought you were lost to us. Especially after you came here with that painted woman. The dancer. But that was about more than a young man’s lust, wasn’t it? I’ve lived through three quarters of a century, Rime. Do you think I’ve never heard of blindcraft? She did something to you, that much I know. You don’t need to say what. I assume it’s what you needed to follow Hirka. And yes, you killed Svarteld. Your own master. But that was his choice, not yours. You were deceived. What man wouldn’t have done the same in your shoes?”

Rime looked away. Lindri’s understanding was harder to bear than any judgement would have been.

“Rime … You’re a young man. I wish I could tell you that distinguishing right from wrong gets easier with age, but it’s not like that. Quite the opposite. The older you get, the more you see. And I’ve seen too many of people’s flaws and shortcomings to think making the right choice is easy.”

Rime snorted. “That’s not what she says …”

“Hirka didn’t grow up in Eisvaldr. You did. You’re a son of the Council. You were never taught the right thing to do. You were taught that as long as you were the one doing it, it’s right. The families are the law. The law is the families. But still you’re fighting an internal battle, and that makes you a good man, Rime. A strong man. Only strong men can withstand losing everything.”

“And strong women,” Rime answered. He felt his shoulders sag. He clinked his cup against Lindri’s, spilling a few drops that soaked into the wood before he could wipe them up.

“Do you know why she’s doing it, Lindri? She thinks she’s stopping a war. She thinks she can talk them out of their bloodlust. That’s what she’s doing. She thinks she can convince blindlings of the merits of peace. Stupid girl. She could annoy the moss off a rock, and she’s going to rile them up more than ever.”

Lindri tried to hide a smile.

Rime drank the rest of the tea. “What?”

“She brings out the best and the worst in you, Rime.”

It was true. But it didn’t matter anymore. She didn’t belong to him. Never would. She’d chosen another world. Another life. If they met again, it would be on the battlefield. And he couldn’t sit idly by, waiting for that to happen. He had to act.

But first a little rest. Here. At the table.

“Darkdaggar controls the Council, Lindri. Controls the army.”

“Yes, so you keep saying.”

“But not Kolkagga. They’re far more dangerous than Mannfalla’s army. Only they can stand against the blind. He mustn’t gain control over them, too, Lindri.”

Rime tried to give voice to his thoughts, but they had slipped away from him and were hopelessly out of reach. Like Kolkagga. The black shadows who were out of Darkdaggar’s reach. But how loyal were they to the Council now? Who had taken over from Svarteld? And how would they receive Rime? The man who had killed his own master? Their master.

“Am I still Kolkagga? What do they think of me now?”

“There’s no way of knowing, Rime.”

“I have to find out. I have no choice.”

“You can find out tomorrow.”

Rime felt a blanket over his back and realized he was falling asleep.

A PROBLEM

The snow was so heavy that Hirka couldn’t see where she was putting her feet. The wind had gotten colder, chilling her to the core. She’d put on every single item of clothing she had. The shirt from Stefan, the spare jumper, and the raincoat from Father Brody pulled over the cloak from Jarladin. All from people she might never see again. Maybe she would never see anyone again.

So far everything seemed to suggest that she would be lost to the snow in this frozen wasteland. The blind would get tired of waiting for her and simply leave her behind, and a hundred years from now they would dig up a cadaver not unlike Graal’s dead raven. Skin and bones in a shirt emblazoned with English words that wouldn’t mean anything to anyone.

Hirka forced a smile. She was surrounded by deadborn, in the kind of weather people went missing in, and she had no idea where she was going. She’d have to keep her spirits up if she were to survive.

They slogged their way up a steep slope that seemed to merge with the sky. A bluish-white expanse that dazzled her if she looked at it for too long. So far she hadn’t seen a single tree or any other people. Just ice and snow.

Hirka tensed her jaw to stop her teeth from chattering. Her cheeks were so cold that it felt like they might split open. Beads of sweat had frozen in her hair. She had to heave her feet up out of the snow with every step. The staff helped. A hollow piece of wood that didn’t weigh much but could withstand a lot. They all had one. They’d told her it was to breathe through if they got caught in an avalanche, and that it also helped people find you. As far as she could tell, they weren’t joking.

Hirka knew she’d have to stop soon. She could taste blood.

She squinted ahead. Skerri was walking at a relentless pace, leaving a trail that made it easier for everyone walking behind. Hirka hadn’t seen her pull her cloak around herself once. It was a wonder she hadn’t frozen to death.

She was carrying a leather tube on her back. It looked like a quiver, but it was too big for arrows. Hirka didn’t hold out much hope for it being a blanket.

Every time Skerri looked around to check on Hirka, the beads in her black braids beat against the quiver like hail. The sound had started to take on new meaning. An accusation that pushed Hirka onward.

“So who’s Modrasme?” Hirka shouted, hoping conversation would slow her down.

“The eldest of our house,” Skerri replied. She glanced at Hirka. “Of your house,” she added. She made it sound more threatening than reassuring.

“So the houses are named after the eld—”

“We’ll talk once we’ve arrived.”

Hirka bit her lip. Maybe one of the others would be more forthcoming. She looked over her shoulder. The three men were following her in single file. The one bringing up the rear was called Hungl. A guardsman type with dark hair and a goatee. Grid walked ahead of him. He wasn’t wearing much either, and he was the only one Skerri had exchanged words with. They seemed to know each other well. Had his hair not been as fair as Skerri’s was dark, Hirka might have thought they were siblings. That said, it was rare for Umpiri to have more than one child, and that seemed to be what had given Graal and Naiell the standing they’d had before the war.

The man with the steely gray hair and the sheepskin around his shoulders walked just behind Hirka. Keskolail. The man who had fired the arrow. Hirka wavered for a moment, but then exhaustion won out over fear and she stopped to wait.

Skerri grabbed her arm and pulled her onward.

“Don’t talk to the fallen,” she said.

“Who are—”

“We’ll discuss his punishment when we reach the camp.”

Camp …

The word alone was like the warmth from a fire. Hirka suddenly felt reinvigorated. She put her head down and trudged onward.

But why would he be punished? Hirka stole a glance at the killer behind her. At the teardrop in his forehead. None of the others had one. He still hadn’t looked at her. It was as if she didn’t exist to him. And clearly he wasn’t supposed to exist to her either.

The slope became so steep that Hirka had to use her hands to aid her progress. She avoided looking at her fingers. They were bound to be blue. At least the snow wasn’t as heavy up here.

“Don’t you have roads?” Hirka asked.

Skerri looked at her over her shoulder. “Roads? You think you’re ready to be seen?”

It didn’t sound like she was expecting a response, so Hirka held her tongue.

The ground leveled out as they emerged onto a snow-covered plateau. Windswept birches crept along the ground. The first trees that Hirka had seen. A raven screeched. She couldn’t see it, but she was so relieved that a lump formed in her throat. There was life here. Life other than the blind.

A group of pointed tents jutted up from the other side of the plateau. They were weighed down by snow on one side, but the canvas still yielded to the wind. Hirka looked around, spotting at least three places that would have provided better cover. It was as if no one had given it any thought.

Any hope of a cart and a hot meal was quashed. She wouldn’t be getting any of that here. Realizing she was falling behind again, she hurried after Skerri.

“Is this the camp?” she asked. “You sleep here? In the open?”

“Yes.”

“But … What about predators?”

Skerri looked at her. A frown line cut down toward her nose. “What are you trying to say?”

“That maybe we should … What if we’re attacked?”

Skerri bared her teeth. Hirka took a step back, almost falling. Umpiri didn’t need to fear predators. They were predators.

“Are you saying we wouldn’t survive an attack?”

Hirka shook her head. “No. No, not at all. I was thinking more about … well, me, I suppose …” She trailed off, shrinking under Skerri’s gaze. She felt like a hair in a bowl of soup.

Hot soup …

Skerri started walking again. Hirka followed, making a mental note of things she now knew not to ask about. Horses. Carts were probably out, too. As was anything that might suggest Umpiri couldn’t rely on their own two feet. Or that they were tired. Or that they had anything whatsoever to fear.

Two deadborn came toward them. Both women, but very different. One was dark-haired and wore a long robe, like an augur or one of the learned. The other was blond and wore leather and fur like a hunter. Or a warrior, if her fierce expression was anything to go by. They spoke to Skerri in a language that Hirka didn’t understand. The language of the blind.

The language of Umpiri.

It was strange yet somehow familiar. The words resonated with her. It was like smelling something for the first time since you were a child. New, but just as much a part of you.

The two women looked at Hirka, both dipping one of their knees in some kind of greeting. Hirka had a feeling she ought to do the same. No sooner had she done so than a hand gripped her neck. Skerri had a hold of her and was steering her toward a tent. She pushed Hirka past the animal pelt serving as a tent flap. Hirka stumbled inside. She waited for Skerri to follow, but she stayed outside, barking orders at the others.

That suited Hirka just fine. She looked around. There was barely room for two. The tent was held up by a pole in the middle. The ground was uneven but dry, even though it was made of cloth. It was probably layered. Or greased underneath. Two woollen blankets lay rolled up on an animal skin. There was nothing else. Not even an oil lamp or anything to drink from.

Hirka dropped her staff and sank to her knees. She was thirsty, hungry, and tired, but she didn’t know which was most pressing.

Thirst.

She took off her bag and untied the waterskin from the outside. She’d tried to drink along the way, but breaks had been few and far between, and the water had been too cold. She fumbled with the cork. It was frozen fast and she didn’t have the strength to get it out. Her fingers were completely numb.

Her eyes started to sting. She was dangerously close to tears. What was wrong with her? Would she cry on the first day, in a place she’d chosen to come to? She had to remember that she was doing this for peace. So the deadborn wouldn’t lay waste to Ym. She had to focus on that. Peace. That and obtaining the knowledge she needed to free Rime from the beak.

She closed her eyes. He had a beak in his throat. A raven’s beak. Graal had power over him, just like he’d had over Urd. And Urd had rotted …

Hirka tossed the waterskin aside. Feeling an annoying lump of snow under the floor, she started bashing it with her fists.

What had she expected? What kind of people had she thought she’d find here? A family? Had she really been that naïve? Was she still nothing more than a girl who longed to feel at home somewhere?

The tent flap was torn aside. Skerri came in. Hirka leaped to her feet. She jumped every time she saw Skerri’s face. Black hair and black lips against pale skin. Hirka would have guessed she was around twenty-five winters had she not been Umpiri. Young, almost girlish. An unnerving combination of beauty and danger.

“Sit,” she snapped. Hirka did as she was told.

Skerri sat across from her. Her corset of leather straps creaked as it yielded to her lithe body.

“Kuro,” she said, nodding at the box tied to the top of Hirka’s bag.

“Kuro?” Hirka hadn’t expected to hear that name here. That was hers. Something she’d come up with when Naiell was still a raven.

“Heart,” Skerri said impatiently. “It means heart. Let me see him.”

Hirka would have smiled at that revelation, had she had the energy. She removed the box from her bag and held it in her lap. It was unassuming, considering its contents. A boring metal box, tarnished as a worn knife blade. Cold against her fingers. Before she’d passed through the gateways, she’d been worried that the ice inside might melt. If only she’d known …

Hirka undid the catches on the sides and lifted the lid. Naiell’s heart lay buried in crushed ice. Pale as a clenched fist. Hirka imagined she could still smell him. Graal’s brother. Her father’s brother. In Ym, he had been the Seer. Here in Dreysíl, he was something else entirely. A criminal. The enemy of the people.

Skerri snatched the box. Closed her eyes and took a deep breath, as if the smell could sustain her. Her lips twisted into a sneer.

“Naiell …”

It was a whisper so thick with hatred that Hirka realized she must have been very close to him. They must have known each other. Hirka stared at her. “You were there …”

Skerri opened her eyes. Milky. Distant. Fixed on something far beyond the small tent. “I swore an oath when the war ended. When I realized he’d betrayed us. When I saw him shackle and humiliate his brother. I swore I’d tear his heart out with my own claws. For a thousand years I’ve waited to smell him again. A thousand years. And now here he is. What more remains than to take back what is ours?”

Hirka didn’t reply. She feared even one wrong word would make Skerri go for her throat. Her black lips twitched. The deadborn woman was grappling with a history that Hirka hadn’t been part of. Was that why she was so angry? Because Hirka had brought them his heart? Had Rime done what Skerri would have preferred to do herself?

The air was thick with Skerri’s disdain. Hirka nudged the lid with her finger and it clicked shut, snapping Skerri out of her trance. She moistened her lips. The color didn’t fade. Was it an inking? Had she dyed them black?

She set the box aside.

“We have a problem, Hirka.” She shook her head and her braids whipped back and forth, as if she were an animal shaking itself dry.

“What sort of problem?”

“You.”

Hirka wanted to protest, but she was too nervous. And begrudgingly curious as to what was wrong with her.

Skerri cocked her head. A birdlike movement that made Hirka think of Graal and Naiell. She ventured to ask a question.

“Skerri, are we family?”

Skerri blinked as if thrown off guard, but she recovered quickly. “We are family, but not by blood. We belong to the same house. You’ll meet your blood relatives once we reach Ginnungad, and therein lies the problem. I need to send the raven now. I need to tell them you’re here. That you’ve arrived. But what am I to say?”

“What do you mean?”

Skerri lifted her chin, looking down her nose at Hirka as if she were an idiot. “You’re like them! Look at yourself! You have eyes like them. You have no claws. No teeth. You’re slow. Weak. Pathetic, like them. You’re more menskr than Umpiri. And this so-called language is nothing short of primitive.”

Hirka’s features stiffened. Shame came creeping, as if she had been thrown back in time. She was in Elveroa again. With Father, who had always tried to hide her because he knew what she was. With Ilume, who’d dismissed her whenever she’d come looking for Rime. She was the monster. The tailless child of Odin. Even here.

She was little again. And it annoyed her. Hirka gritted her teeth.

“Sorry if I’m not what you expected.”

Skerri snorted. “Apologizing won’t help. You need to learn our ways before you can be presented, and time isn’t on our side. To be honest, I knew we’d have this problem as soon as I heard about you. Graal was somewhat … evasive.”

“So you’re the one who talks to him?”

“Me. Nobody else.”

The pride in her voice didn’t escape Hirka’s notice. Graal meant something, and that was probably the only reason she was still alive. But that didn’t mean she would suffer through a lecture about everything that was wrong with her. She’d done that far too many times before.

“Just tell me what needs to be done, Skerri.”

Skerri studied her for a moment. Then she stood abruptly. “I’ll tell them you’ve arrived. That’s all. Then we’ll see what can be done. Language is our most pressing concern. Our house cannot be defiled by your language. Oni will instruct you on the way.”

“Oni?”

“A servant. She works for the house. She is learned and can teach you to speak properly. And how to behave.” Skerri looked her up and down. “We’ll do something about your clothes later.”

Language, behavior, clothes … Hirka couldn’t have cared less. What she really needed was someone who understood the Might.

“What about …” Hirka almost said blindcraft but then caught herself. “What about the Might? I need to talk to someone who can teach me about the beaks.” She raised a hand to her throat to illustrate what she meant.

Skerri gave her an empty stare.

Hirka had to find a different approach. Something that would force Skerri to help. Force her to answer. In other words, she would have to hit her where it hurt. Her pride.

“Are you telling me you have no one learned in the Might?”

Skerri’s eyes narrowed to white slits. “Of course we do! The best! We have mightslingers and seers, but no one you need concern yourself with. They are not your priority.”

Seers? The blind had seers?

Of course they do. Where else would he have gotten the idea?

Hirka couldn’t help but laugh. Naiell hadn’t been able to abandon his own world entirely.

Skerri turned to leave. “This is your tent,” she said. “Stay here. Oni will come and get you once I’ve sent the raven. Then you’ll meet the others.”

She swept the tent flap aside. Light streamed in and across the floor. She looked at Hirka again. “And one more thing: if you ever bend the knee to anyone below your house again, I’ll have your kneecaps.”

Skerri stormed out, braids whipping after her.

Hirka closed her eyes.

Don’t ask about horses. Don’t question camp locations. Don’t bend your knees.

JUDGEMENT

Hirka had been desperate for clarity. For information. But it was starting to dawn on her that too much information was worse than none.

Oni meant tongue in umǫni, which was their language. It was also what everyone called the woman who was to be her teacher, and Hirka could understand why. Oni never stopped talking. And unlike Skerri, she seemed to have no qualms about speaking ymish, but then, she was too young to have fought in the war. It made her more curious than Skerri, and probably less prejudiced.

She’d been studying the language for two years, at Skerri’s request. Request was Oni’s word, but Hirka suspected order would be more accurate. It was only now that her would-be teacher had discovered why it was necessary. It was a well-guarded secret that the stone circles weren’t all dead.