Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

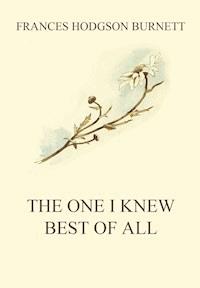

To say that Mrs. Burnett's account of 'The One I Knew Best of All' is a fascinating book, is to put the matter very mildly. It is not one little girl alone whose experiences are here recorded, but, as the author justly claims, it is the story of any child with an imagination. Mrs. Burnett's recollections go back to a very early age; she remembers events that happened before she was three years old, and she cannot remember a time when she was not capable of forming decided opinions about things. Mrs. Burnett has written many attractive books-books that have made friends for her all over the world-but she has never written a book more charming than this. The naiveté, candor, and utter unpretentiousness of it are qualities that give it an enduring fascination.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 327

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ONE I KNEW THE BEST OF ALL

A Memory of the Mind of a Child

FRANCES HODGSON BURNETT

The One I Knew The Best Of All, F. Hodgson Burnett

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849649012

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

Preface. 1

Chapter I - The One I Knew the Best of All2

Chapter II - The Little Flower Book and the Brawn Testament11

Chapter III - The Back Garden of Eden. 14

Chapter IV. - Literature and the Doll.20

Chapter V. - Islington Square,32

Chapter VI. - A Confidence Betrayed. 41

Chapter VII. The Secretaire. 50

Chapter VIII. The Party. 59

Chapter IX. The Wedding. 65

Chapter X. The Strange Thing. 71

Chapter XI. " Mamma " — and the First One. 80

Chapter XII. " Edith Somerville " — and Raw Turnips. 94

Chapter XIII. Christopher Columbus103

Chapter XIV. The Dryad Days. 113

Chapter XVI. And So She Did. 140

PREFACE

I SHOULD feel a serious delicacy in presenting to the world a sketch so autobiographical as this if I did not feel myself absolved from any charge of the bad taste of personality by the fact that I believe I might fairly entitle it " The Story of any Child with an Imagination." My impression is that the Small Person differed from a world of others only in as far as she had more or less imagination than other little girls. I have so often wished that I could see the minds of young things with a sight stronger than that of very interested eyes, which can only see from the outside. There must be so many thoughts for which child courage and child language have not the exact words. So, remembering that there was one child of whom I could write from the inside point of view, and with certain knowledge, I began to make a little sketch of the one I knew the best of all. It was only to be a short sketch in my first intention, but when I began it I found so much to record which seemed to me amusing and illustrative, that the short sketch became a long one. After all, it was not myself about whom I was being diffuse, but a little unit of whose parallels there are tens of thousands. The Small Person is gone to that undiscoverable far-away land where other Small Persons have emigrated — the land to whose regretted countries there wandered, some years ago, two little fellows, with picture faces and golden love-locks, whom I have mourned and longed for ever since, and whose going — with my kisses on their little mouths — has left me forever a sadder woman, as all other mothers are sadder, whatsoever the dearness of the maturer creature left behind to bear the same name and smile with eyes not quite the same. As I might write freely about them, so I feel I may write freely about her.

Frances Hodgson Burnett.

May, 1892.

Chapter I - The One I Knew the Best of All

I HAD every opportunity for knowing her well, at least. We were born on the same day, we learned to toddle about together, we began our earliest observations of the world we lived in at the same period, we made the same mental remarks on people and things, and reserved to ourselves exactly the same rights of private personal opinion. I have not the remotest idea of what she looked like. She belonged to an era when photography was not as advanced an art as it is to-day, and no picture of her was ever made. It is a well-authenticated fact that she was auburn-haired and rosy, and I can testify that she was curly, because one of my earliest recollections of her emotions is a memory of the momentarily maddening effect of a sharp, stinging jerk of the comb when the nurse was absent-minded or maladroit. That she was also a plump little person I am led to believe, in consequence of the well-known joke of a ribald boy cousin and a disrespectful brother, who averred that when she fell she bounced like an india-rubber ball. For the rest, I do not remember what the looking-glass reflected back at her, though I must have seen it. It might, consequently, be argued that on such occasions there were so many serious and interesting problems to be attended to that a reflection in the looking-glass was an unimportant detail.

In those early days I did not find her personally interesting — in fact, I do not remember regarding her as a personality at all. It was the people about her, the things she saw, the events which made up her small existence, which were absorbing, exciting, and of the most vital and terrible importance sometimes. It was not until I had children of my own, and had watched their small individualities forming themselves, their large imaginations giving proportions and values to things, that I began to remember her as a little Person; and in going back into her past and reflecting on certain details of it and their curious effects upon her, I found interest in her and instruction, and the most serious cause for tender deep reflection on her as a thing touching on that strange, awful problem of a little soul standing in its newness in the great busy, tragic world of life, touched for the first time by everything that passes it, and never touched without some sign of the contact being left upon it.

What I remember most clearly and feel most serious is one thing above all: it is that I have no memory of any time so early in her life that she was not a distinct little individual. Of the time when she was not old enough to formulate opinions quite clearly to herself I have no recollection, and I can remember distinctly events which happened before she was three years old. The first incident which appears to me as being interesting, as an illustration of what a baby mind is doing, occurred a week or so after the birth of her sister, who was two years younger than herself. It is so natural, so almost inevitable, that even the most child-loving among us should find it difficult to realize constantly that a mite of three or four, tumbling about, playing with india-rubber dogs and with difficulty restrained from sucking the paint off Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japhet, not to mention the animals, is a person" and that this person is ten thousand times more sensitive to impression than one's self, and that hearing and seeing one, this person, though he or she may not really understand, will be likely, in intervals of innocent destruction of small portable articles, to search diligently in infant mental space until he or she has found an explanation of affairs, to be pigeon-holed for future reference. And yet I can most solemnly declare that such was the earliest habit of that " One I knew the best of all."

One takes a fat, comfortable little body on one's knee and begins to tell it a story about " a fairy "or "a doggie" or "a pussy." And the moment the story begins the questions begin also. And with my recollection of the intense little Bogie whom I knew so well and who certainly must have been a most e very-day-looking little personage, giving no outward warning of preternatural alertness and tragic earnestness, my memory leads me to think that indeed it is not a trifle to be sufficiently upright and intelligent to answer these questions exactly as one should. This first incident, which seems to me to denote how early a tiny mind goes through distinct processes of thought, is a very clear memory to me.

I see a comfortable English bedroom, such as would to-day seem old-fashioned without being ancient enough to be picturesque. I remember no articles of furniture in the room but a rather heavy four-posted carved mahogany bed, hung with crimson damask, ornamented with heavy fringe and big cords and tassels, a chair by this bedside — I think it was an arm-chair covered with chintz — and a footstool. This was called " a buffet," and rhymed with Miss Muffet eating her curds and whey. In England Miss Muffet sat on " a buffet " on the blood-curdling occasion when

" There came a big spider

And sat down beside her

And frightened Miss Muffet away."

This buffet was placed upon the hearth-rug before the fire, and a very small being was sitting upon it, very conscious, in a quiet way, of her mamma lying on the crimson-draped bed, and the lady friend who was sitting in the chair by her, discussing their respective new babies. But most of all was the Small Person on the buffet conscious of their own personal new baby who was being taken care of by a nurse just near her.

Perhaps the interest of such recollections is somewhat added to by the fact that one can only recall them by episodes, and that the episodes seem to appear without any future or any past. Not the faintest shadow of the new baby seems to appear upon the camera, up to this moment, of the buffet, and I have no remembrance of any mental process which led to the Small Person's wishing to hold it on her knee. Perhaps it was a sudden inspiration.

But she did wish to hold it, and notified as much, apparently with sufficient clearness, to the nurse.

The shadow of the nurse has no name and no special individuality. She was only a figure known as " The Nurse "

But she impresses me in these days as having been quite definite in her idea that Persons not yet three years old were not to be trusted entirely with the new-born, however excellent their intentions were.

How the Small Person expressed herself in those days I do not know at all. Before three years articulation is not generally perfect, but if hers was not I know she was entirely unaware of her inadequacies. She thought she spoke just as other people did, and I never remember her pronunciation being corrected. I can recall, with perfect distinctness, however, what she thought she expressed and what her hearers seemed to understand her to say.

It was in effect something like this:

" I want to hold the

New Baby on my knee. "

" You are too little," said the Nurse.

"No, I am not too little. The New Baby is little, and I am on the buffet, and I will hold her tight if you will put her on my knee."

" She would slip off, I am afraid."

" No, I will hold her tight with both arms, just like you do. Please give her to me." And the Small Person spread her small knees.

I don't know how long the discussion lasted, but the Nurse was a good-natured person, and at last she knelt down upon the hearth-rug by the buffet, holding the white-robed new baby in her arms, and amiably pretended to place it in the short arms and on the tiny knees, while she was really supporting it herself.

" There," she said. " Now she is on your knee." She thought she had made it all right, but she was gravely mistaken.

" But I want to hold her myself"' said the Small Person.

" You are holding her," answered the Nurse, cheerfully. " What a big girl to be holding the New Baby just like a grown-up lady."

The Small Person looked at her with serious candor.

" I am not holding her," she said. " You are holding her."

That the episode ended without the Small Person either having held the New Baby, or being deceived into fancying she held it, is as clear a memory to me as if it had occurred yesterday; and the point of the incident is that after all the years that have passed I remember with equal distinctness the thoughts which were in the Small Person's mind as she looked at the Nurse and summed the matter up, while the woman imagined she was a baby not capable of thinking at all.

It has always interested me to recall this because it was so long ago, and while it has not faded out at all, and I see the mental attitude as definitely as I see the child and the four-post bed with its hangings, I recognize that she was too young to have had in her vocabulary the -words to put her thoughts and mental arguments into — and yet they were there, as thoughts and mental arguments are there to-day — and after these many years I can write them in adult words without the slightest difficulty. I should like to have a picture of her eyes and the expression of her baby face as she looked at the nurse and thought these things, but perhaps her looks were as inarticulate as her speech.

" I am very little," she thought. " I am so little that you think I do not know that you are pretending that I am holding the new baby, while really it is you who are holding it. But I do know. I know it as well as you, though I am so little and you are so big that you always hold babies. But I cannot make you understand that, so it is no use talking. I want the baby, but you think I shall let it fall. I am sure I shall not. But you are a grown-up person and I am a little child, and the big people can always have their own way."

I do not remember any rebellion against an idea of injustice. All that comes back to me in the form of a mental attitude is a perfect realization of the immense fact that people who were grown up could do what they chose, and that there was no appeal against their omnipotence.

It may be that this line of thought was an infant indication of a nature which developed later as one of its chief characteristics, a habit of adjusting itself silently to the inevitable, which was frequently considered to represent indifference, but which merely evolved itself from private conclusions arrived at through a private realization of the utter uselessness of struggle against the Fixed.

The same curiosity as to the method in which the thoughts expressed themselves to the small mind devours me when I recall the remainder of the bedroom episode, or rather an incident of the same morning.

The lady visitor who sat in the chair was a neighbor, and she also was the proprietor of a new baby, though her baby was a few weeks older than the very new one the Nurse held.

She was the young mother of two or three children, and had a pretty sociable manner toward tiny things. The next thing I see is that the Small Person had been called up to her and stood by the bed in an attitude of modest decorum, being questioned and talked to.

I have no doubt she was asked how she liked the New Baby, but I do not remember that or anything but the serious situation which arose as the result of one of the questions. It was the first social difficulty of the Small Person — the first confronting of the overwhelming problem of how to adjust perfect truth to perfect politeness.

Language seems required to mentally confront this problem and try to settle it, and the Small Person cannot have had words, yet it is certain that she confronted and wrestled with it.

" And what is your New Baby's name to be? " the lady asked.

" Edith" was the answer.

" That is a pretty name," said the lady. " I have a new baby, and I have called it Eleanor. Is not that a pretty name? "

In this manner it was — simple as it may seem — that the awful problem presented itself. That it seemed awful — actually almost unbearable — is an illustration of the strange, touching sensitiveness of the new-born butterfly soul just emerged from its chrysalis — the impressionable sensitiveness which it seems so tragic that we do not always remember.

For some reason — it would be impossible to tell what — the Small Person did not think Eleanor was a pretty name. On strictly searching the innermost recesses of her diminutive mentality she found that she could not think it a pretty name. She tried, as if by muscular effort, and could not. She thought it was an ugly name; that was the anguish of it. And here was a lady, a nice lady, a friend with whom her own mamma took tea, a kind lady, who had had the calamity to have her own newest baby christened by an ugly name. How could anyone be rude and hard-hearted enough to tell her what she had done — that her new baby would always have to be called something ugly? She positively quaked with misery. She stood quite still and looked at the poor nice lady helplessly without speaking. The lady probably thought she was shy, or too little to answer readily or really have any opinion on the subject of names. Mistaken lady: how mistaken, I can remember. The Small Person was wrestling with her first society problem, and trying to decide what she must do with it.

" Don't you think it is a pretty name? " the visitor went on, in a petting, coaxing voice, possibly with a view to encouraging her. " Don't you like it? "

The Small Person looked at her with yearning eyes. She could not say " No " blankly. Even then there lurked in her system the seeds of a feeling which, being founded on a friendly wish to be humane which is a virtue at the outset, has increased with years, until it has become a weakness which is a vice. She could not say a thing she did not mean, but she could not say brutally the unpleasant thing she did mean. She ended with a pathetic compromise.

" I don't think," she faltered— " I don't think— it is — as pretty — as Edith."

And then the grown-up people laughed gayly at her as if she were an amusing little thing, and she was kissed and cuddled and petted. And nobody suspected she had been thinking anything at all, any more than they imagined that she had been translating their remarks into ancient Greek. I have a vivid imagination as regards children, but if I had been inventing a story of a child, it would not have occurred to me to imagine such a mental episode in such a very tiny person. But the vividness of my recollection of this thing has been a source of interest and amusement to me through so many mature years that I feel it has a certain significance as impressing upon one's mind a usually unrealized fact.

When she was about four years old a strange and serious event happened in the household of the Small Person, an event which might have made a deep and awesome impression on her but for two facts. As it was, a deep impression was made, but its effect was not of awfulness, but of unexplainable mystery. The thing which happened was that the father of the Small Person died. As she belonged to the period of Nurses and the Nursery she did not feel very familiar with him, and did not see him very often. " Papa," in her mind, was represented by a gentleman who had curling brown hair and who laughed and said affectionately funny things. These things gave her the impression of his being a most agreeable relative, but she did not know that the funny things were the jocular remarks with which good-natured maturity generally salutes tender years.

He was intimately connected with jokes about cakes kept in the dining-room sideboard, and with amiable witticisms about certain very tiny glasses of sherry in which she and her brothers had drunk his health and her mamma's, standing by the table after dinner, when there were nuts and other fruits adorning it. These tiny glasses, which must really have been liqueur glasses, she thought had been made specially small for the accommodation of persons from the Nursery.

When " papa " became ill the Nursery was evidently kept kindly and wisely in ignorance of his danger. The Small Person's first knowledge of it seemed to reach her through an interesting adventure. She and her brothers and the New Baby, who by this time was quite an old baby, were taken away from home. In a very pretty countrified Public Park not far away from where she lived there was a house where people could stay and be made comfortable. The Park still exists, but I think the house has been added to and made into a museum. At that time it appeared to an infant imagination a very splendid and awe-inspiring mansion. It seemed very wonderful indeed to live in a house in the Park where one was only admitted usually under the care of Nurses who took one to walk. The park seemed to become one's own private garden, the Refreshment Room containing the buns almost part of one's private establishment, and the Policemen, after one's first awe of them was modified, to become almost mortal men.

It was a Policeman who is the chief feature of this period. He must have been an amiable Policeman. I have no doubt he was quite a fatherly Policeman, but the agonies of terror the One I knew the best of all passed through in consequence of his disposition to treat her as a joke, are something never to be forgotten.

I can see now from afar that she was a little person of the most law-abiding tendencies. I can never remember her feeling the slightest inclination to break a known law of any kind. Her inward desire was to be a good child. Without actually formulating the idea, she had a standard of her own. She did not want to be " naughty," she did not want to be scolded, she was peace-loving and pleasure-loving, two things not compatible with insubordination. When she was " naughty," it was because what seemed to her injustice and outrage roused her to fury. She had occasional furies, but went no further.

When she was told that there were pieces of grass on which she must not walk, and that on the little boards adorning their borders the black letters written said, " Trespassers will be prosecuted," she would not for worlds have set her foot upon the green, even though she did not know what " prosecuted " meant. But when she discovered that the Park Policemen who walked up and down in stately solitude were placed by certain awful authorities to "take up" anybody who trespassed, the dread that she might inadvertently trespass some day and be "taken up" caused her blood to turn cold.

What an irate Policeman, rendered furious by an outraged law, represented to her tender mind I cannot quite clearly define, but I am certain that a Policeman seemed an omnipotent power, with whom the boldest would not dream of trifling, and the sole object of whose majestic existence was to bring to swift, unerring justice the juvenile law-breakers who in the madness of their youth drew upon themselves the eagle glance of his wrath, the awful punishment of justice being to be torn shrieking from one's Mamma and incarcerated for life in a gloomy dungeon in the bowels of the earth. This was what " Prison " and being " taken up " meant.

It may be imagined, then, with what reverent awe she regarded this supernatural being from afar, clinging to her Nurse's skirts with positively bated breath when he appeared; how ostentatiously she avoided the grass which must not be trodden upon; how she was filled with mingled terror and gratitude when she discovered that he even descended from his celestial heights to speak to Nurses, actually in a jocular manner and with no air of secreting an intention of pouncing upon their charges and " taking them up " in the very wantonness of power.

I do not know through what means she reached the point of being sufficiently intimate with a Policeman to exchange respectful greetings with him and even to indulge in timorous conversation. The process must have been a very gradual one and much assisted by friendly and mild advances from the Policeman himself. I only know it came about, and this I know through a recollection of a certain eventful morning.

It was a beautiful morning, so beautiful that even a Policeman might have been softened by it. The grass which must not be walked upon was freshest green, the beds of flowers upon it were all in bloom. Perhaps the brightness of the sunshine and the friendliness of nature emboldened the Small Person and gave her giant strength.

How she got there I do not know, but she was sitting on one of the Park benches at the edge of the grass, and a Policeman — a real, august Policeman — was sitting beside her.

Perhaps her Nurse had put her there for a moment and left her under the friendly official's care. But I do not know. I only know she was there, and so was he, and he was doing nothing alarming. The seat was one of those which have only one piece of wood for a back and she was so little that her short legs stuck out straight before her, confronting her with short socks and plump pink calf and small " ankle-strap " shoes, while her head was not high enough to rest itself against the back, even if it had wished to.

It was this last fact which suggested to her mind the possibility of a catastrophe so harrowing that mere mental anguish forced her to ask questions even from a minion of the law. She looked at him and opened her lips half a dozen times before she dared to speak, but the words came forth at last:

" If anyone treads on the grass must you take them up? "

" Yes, I must." There is no doubt but that the innocent fellow thought her and her question a good joke.

"Would you have to take anyone up if they went on the grass? "

"Yes," with an air of much official sternness. "" Anyone"

She panted a little and looked at him appealingly. " Would you have to take me up if I went on it? " Possibly she hoped for leniency because he evidently did not object to her Nurse, and she felt that such relationship might have a softening influence.

" Yes," he said, " I should have to take you to prison."

" But," she faltered, " but if I couldn't help it— if I didn't go on it on purpose."

" You'd have to be taken to prison if you went on it," he said. " You couldn't go on it without knowing it."

She turned and looked at the back of the seat, which was too high for her head to reach, and which consequently left no support behind her exceeding smallness.

" But — but," she said, " I am so little I might fall through the back of this seat. If I was to fall through on to the grass should you take me to prison.""

What dullness of his kindly nature — I feel sure he was not an unkindly fellow — blinded the Policeman to the terror and consternation which must in some degree have expressed themselves on her tiny face, I do not understand, but he evidently saw nothing of them. I do not remember what his face looked like, only that it did not wear the ferocity which would have accorded with his awful words.

" Yes," he said, " I should have to pick you up and carry you at once to prison."

She must have turned pale; but that she sat still without further comment, that she did not burst into frantic howls of despair, causes one to feel that even in those early days she was governed by some rudimentary sense of dignity and resignation to fate, for as she sat there, the short legs in socks and small black "ankle-straps " confronting her, the marrow was dissolving in her infant bones.

There is doubtless suggestion as to the limits and exaggerations of the tender mind in the fact that this incident was an awful one to her and caused her to waken in her bed at night and quake with horror, while the later episode of her hearing that " Poor Papa " had died seemed only to be a thing of mystery of which there was so little explanation that it was not terrible. This was without doubt because, to a very young child's mind, death is an idea too vague to grasp.

There came a day when someone carried her into the bedroom where the crimson-draped four-post bed was, and standing by its side held her in her arms that she might look down at Papa lying quite still upon the pillow. She only thought he looked as if he were asleep, though someone said: " Papa has gone to Heaven," and she was not frightened, and looked down with quiet, interest and respect. A few years later the sight of a child of her own age or near it, lying in his coffin, brought to her young being an awed realization of death, whose anguished intensity has never wholly repeated itself; but being held up in kind arms to look down at " Poor Papa," she only gazed without comprehension and without fear.

Chapter II - The Little Flower Book and the Brawn Testament

I DO not remember the process by which she learned to read or how long a time it took her. There was a time when she sat on a buffet before the Nursery fire — which was guarded by a tall wire fender with a brass top — and with the assistance of an accomplished elder brother a few years her senior, seriously and carefully picked out with a short, fat finger the capital letters adorning the advertisement column of a newspaper.

But from this time my memory makes a leap over all detail until an occasion when she stood by her Grandmamma's knee by this same tall Nursery fender and read out slowly and with dignity the first verse of the second chapter of Matthew in a short, broad, little speckled brown Testament with large print.

" When — Jesus — was — born — in — Bethlehem — of Judea," she read, but it is only this first verse I remember.

Either just before or just after the accomplishing of this feat «he heard that she was three years old. Possibly this fact was mentioned as notable in connection with the reading, but to her it was a fact notable principally because it was the first time she remembered hearing that she was any age at all and that birthdays were a feature of human existence.

But though the culminating point of the learning to read was the Brown Testament, the process of acquiring the accomplishment must have had much to do with the " Little Flower Book."

In a life founded and formed upon books, one naturally looks back with affection to the first book one possessed. The one known as the " Little Flower Book " was the first in the existence of the One I knew the best of all.

No other book ever had such fascinations, none ever contained such marvelous suggestions of beauty and story and adventure. And yet it was only a little book out of which one learned one's alphabet.

But it was so beautiful. One could sit on a buffet and pore over the pages of it for hours and thrill with wonder and delight over the little picture which illustrated the fact that A stood for Apple-blossom, C for Carnation, and R for Rose. What would I not give to see those pictures now. But I could not see them now as the Small Person saw them then. I only wish I could. Such lovely pictures! So like real flowers! As one looked at each one of them there grew before one's eyes the whole garden that surrounded it — the very astral body of the beauty of it.

It was rather like the Brown Testament in form. It was short and broad, and its type was large and clear. The short page was divided in two; the upper half was filled with an oblong black background, on which there was a flower, and the lower half with four lines of rhyme beginning with the letter which was the one that " stood for " the flower. The black background was an inspiration, it made the flower so beautiful. I do not remember any of the rhymes, though I have a vague impression that they usually treated of some moral attribute which the flower was supposed to figuratively represent. In the days when the Small Person was a child, morals were never lost sight of; no well-regulated person ever mentioned the Poppy, in writing for youth, without calling it "flaunting" or "gaudy;" the Violet, without laying stress on its " modesty; " the Rose, without calling attention to its " sweetness," and daring indeed would have been the individual who would have referred to the Bee without calling him " busy." Somehow one had the feeling that the Poppy was deliberately scarlet from impudence, that the Violet stayed up all night, as it were, to be modest, that the Rose had invented her own sweetness, and that the Bee would rather perish than be an "idle butterfly " and not spend every moment " improving each shining hour." But we stood it very well. Nobody repined, but I think one rather had a feeling of having been born an innately vicious little person who needed laboring with constantly that one might be made merely endurable.

It never for an instant occurred to the Small Person to resent the moral attributes of the flowers. She was quite resigned to them, though my impression is that she dwelt on them less fondly than on the fact that the rose and her alphabetical companions were such visions of beauty against their oblong background of black.

The appearing of the Flower Book on the horizon was an event in itself. Somehow the Small Person had become devoured by a desire to possess a book and know how to read it. She was the fortunate owner of a delightful and ideal Grandmamma — not a modern grandmamma, but one who might be called a comparatively " early English " grandmamma. She was stately but benevolent; she had silver-white hair, wore a cap with a full white net border, and carried in her pocket an antique silver snuff-box, not used as a snuff-box, but as a receptacle for what was known in that locality as " sweeties," one of which being bestowed with ceremony was regarded as a reward for all nursery virtues and a panacea for all earthly ills. She was bounteous and sympathetic, and desires might hopefully be confided to her. Perhaps this very early craving for literature amused her, perhaps it puzzled her a little. I remember that a suggestion was tentatively made by her that perhaps a doll would finally be found preferable to a book, but it was strenuously declared by the Small Person that a book, and only a book, would satisfy her impassioned cravings. A curious feature of the matter is that, though dolls at a later period were the joy and the greater part of the existence of the Small Person, during her very early years I have absolutely no recollection of a feeling for any doll, or indeed a memory of any dolls existing for her.

So she was taken herself to buy the book. It was a beautiful and solemn pilgrimage. Reason suggests that it was not a long one, in consideration for her tiny and brief legs, but to her it seemed to be a journey of great length — principally past wastes of suburban brick-fields, which for some reason seemed romantic and interesting to her, and it ended in a tiny shop on a sort of country road. I do not see the inside of the shop, only the outside, which had one small window, with toys and sweet things in glass jars. Perhaps the Small Person was left outside to survey these glories. This would seem not improbable, as there remains no memory of the interior. But there the Flower Book was bought (I wonder if it really cost more than sixpence); from there it was carried home under her arm, I feel sure. Where it went to, or how it disappeared, I do not know. For an aeon it seemed to her to be the greater part of her life, and then it melted away, perhaps being absorbed in the Brown Testament and the more dramatic interest of Herod and the Innocents. From her introduction to Herod dated her first acquaintance with the " villain " in drama and romance, and her opinion of his conduct was, I am convinced, founded on something much larger than mere personal feeling.

Chapter III - The Back Garden of Eden

I DO not know with any exactness where it was situated. To-day I believe it is a place swept out of existence. In those days I imagine it was a comfortable, countrified house, with a big garden round it, and fields and trees before and behind it; but if I were to describe it and its resources and surroundings as they appeared to me in the enchanted days when I lived there, I should describe a sort of fairyland.

If one could only make a picture of the places of the world as these Small Persons see them, with their wondrous proportions and beauties — the great heights and depths and masses, the garden-walks which seem like stately avenues, the rose-bushes which are jungles of bloom, the trees adventurous brothers climb up and whose topmost branches seem to lift them to the sky. There was such a tree at the bottom of the garden at Seedly. To the Small Person the garden seemed a mile long. There was a Front Garden and a Back Garden, and it was the Back Garden she liked best and which appeared to her large enough for all one's world. It was all her world during the years she spent there. The Front Garden had a little lawn with flower-beds on it and a gravel walk surrounding it and leading to the Back Garden. The interesting feature of this domain was a wide flower-bed which curved round it and represented to the Small Person a stately jungle. It was filled with flowering shrubs and trees which bloomed, and one could walk beside them and look through the tangle of their branches and stems and imagine the things which might live among them and be concealed in their shadow. There were rose-bushes and lilac-bushes and rhododendrons, and there were laburnums and snowballs. Elephants and tigers might have lurked there, and there might have been fairies or gypsies, though I do not think her mind formulated distinctly anything more than an interesting suggestion of possibilities.

But the Back Garden was full of beautiful wonders. Was it always Spring or Summer there in that enchanted Garden which, out of a whole world, has remained throughout a lifetime the Garden of Eden? Was the sun always shining? Later and more material experience of the English climate leads me to imagine that it was not always flooded and warmed with sunshine, and filled with the scent of roses and mignonette and new-mown hay and apple-blossoms and strawberries all together, and that when one laid down on the grass on one's back one could not always see that high, high world of deep sweet blue with fleecy islets and mountains of snow drifting slowly by or seeming to be quite still — that world to which one seemed somehow to belong even more than to the earth, and which drew one upward with such visions of running over the white soft hills and springing, from little island to little island, across the depths of blue which seemed a sea. But it was always so on the days the One I knew the best of all remembers the garden. This is no doubt because, on the wet days and the windy ones, the cold days and the ugly ones, she was kept in the warm nursery and did not see the altered scene at all.

In the days in which she played out of doors there were roses in bloom, and a score of wonderful annuals, and bushes with gooseberries and red and white and black currants, and raspberries and strawberries, and there was a mysterious and endless seeming alley of Sweetbriar, which smelt delicious when one touched the leaves and which sometimes had a marvelous development in theshape of red berries upon it. How is it that the warm, scented alley of Sweetbriar seems to lead her to an acquaintance, an intimate and friendly acquaintance, with the Rimmers's pigs, and somehow through them to the first Crime of her infancy?