Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

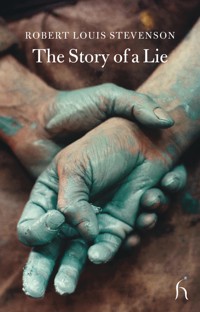

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press Ltd.

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A chance encounter in a Parisian café leads to a series of unfortunate "misunderstandings" which threaten to bring to a premature and irreconcilable end the envisioned marriage between a pair of young lovers. Eligible bachelor Dick Naseby meets the lovely young Esther Van Tromp, whose less-than-respectable father he has had the dubious pleasure of encountering on his travels. Too well-bred and smitten with the lady to confess the truth, he becomes entangled in a series of falsehoods, the ultimate unraveling of which threatens to be his undoing. The Story of a Lie is a lesson in life encompassing art, alcohol, and deceit in all its forms and is presented here alongside Stevenson's celebrated short story The Body Snatcher, a macabre tale of human corruption.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 145

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Story of a Lie

Robert Louis Stevenson

Foreword byD.J. Taylor

Hesperus Classics

Published by Hesperides Press Limited

167-169 5th Floor Great Portland Street W1W 5PF www.hesperus.press

This collection first published by Hesperus Press Limited, 2008

This edition printed 2025

‘The Story of a Lie’ first published in New Quarterly Magazine, 1879

‘The Body Snatcher’ first published in the Pall Mall Gazette, 1884

Foreword © D.J. Taylor, 2008

ISBN (1st edition): 978-1-84391-181-4

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-84391-339-9

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

Foreword

D.J. Taylor

The Story of a Lie

1. Introduces the Admiral

2. A Letter to the Papers

3. In the Admiral

4. Esther on the Filial Relation

5. The Prodigal Father Makes his Debut at Home

6. The Prodigal Father Goes on from Strength to Strength

7. The Elopement

8. Battle Royal

9. In Which the Liberal Editor Re-Appears as ‘Deus Ex Machina’

The Body Snatcher

Biographical Note

Foreword

D.J. Taylor

By the close of the Victorian era, the gap between mass culture and high art—between the bestseller and the slim volume, the daily newspaper and the highbrow weekly—had grown into a chasm. As John Gross observes in his invaluable The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters, if it was the age of Northcliffe and H.G. Wells, then it was also the age of The Yellow Book, The Savoy, The Hobby Horse, and other exquisite trifles so obscure that they have vanished even from the bibliographies. Stevenson’s vantage point on this process of cultural separation is more complicated than it might seem. On the one hand, mainstream critics who admired the dynamism of his action scenes fretted over the subtleties of his characterisation (“More claymores, less psychology,” as Andrew Lang famously demanded). On the other, many a grand literary eminence of the kind that Stevenson was occasionally disposed to mock signified warm approval. In his Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ernest Mehew prints a revealing exchange with Henry James, in which James talks of his “hearty sympathy, charged with the assurance of my enjoyment of everything you write.” And James, it should be pointed out, was not simply being polite. That he regarded the author of Treasure Island as, in some sense, an ally is confirmed by some later remarks about the “luxury” of encountering someone who “does write,” as James put it, and “who is really acquainted with that lovely art.”

The Story of a Lie and The Body Snatcher are characteristic Stevenson productions: written on the hoof, against time, and for money—the latter for the Pall Mall Gazette’s Christmas number of 1884, the former in the course of a stormy Atlantic crossing five years before for the publishing house of Kegan Paul’s New Quarterly Magazine (“I worked… I worked,” runs a letter to W.E. Henley, “and am now despatching a story as long as my arm to the vile Paul, all written in a slantindicular cabin with the table playing bob-cherry with the ink bottle.') Each comes crammed with the psychological detail that caused Lang to wonder whether he hadn't backed the wrong horse. 'The Story of a Lie', in particular, is a devious little parable about the need for absolute transparency in one's personal dealings. Dick Naseby is a strong-willed squire's son who falls out with his hot-tempered father on a point of principle. Travelling in France he comes across a shady-sounding ex-artist named Van Tromp, described as 'a dismal parasite upon the foreigner in Paris', who makes a living out of 'percentages' – that is, escorting his young friends to tradesmen's shops and restaurants and taking a cut of the proceeds from their grateful proprietors. Dick, however, is man of the world enough to see through this imposture, whereupon their association lapses into a wary friendship.

Back in England, Dick falls in love with a young woman living with her aunt in a secluded cottage on the family estate. This, inevitably, is Van Tromp's daughter, not seen by him for many a year, and kept in provincial purdah by her exacting spinster aunt, Miss M'Glashan, on the plausible grounds that she '"couldn't save the mother – her that's dead – but the bairn!"' Encouraged by the tender object of his affections to dilate on her absent father's sterling qualities, his artistic talents, kindness, generosity and so forth, Dick offers a version of the old man that, while not exactly false, gives no idea of his real character. Their brief idyll is shattered by Van Tromp's unexpected return and a brisk series of emotional readjustments – not all of them wholly predictable – in the approved Victorian magazine style. Throughout, Van Tromp remains both the villain of the piece the star of the show, one of those eternally disreputable, down-at-heel idlers in whom Stevenson always delights (Fettes in The Body Snatcher is a variation on this theme), is simultaneously brusque, flustered, and calculating. He is first seen scribbling in a Parisian estaminet, where his vocal style is crisply paraphrased in an explanation of his drawing technique: “‘I just dash them off like that. I—I dash them off.’”

Van Tromp’s signature mark, as Naseby soon discovers, is his poseur’s love of role play. Relocated to the English countryside and the society of his (initially) admiring daughter, he instantly abandons his boulevardier’s cane for a stout stick “designed for rustic scenes,” attends church, looks fondly on the daughter’s choice of husband (“‘Dick, I have been expecting this. Let us—let us go back to the Trevanion Arms and talk this matter out over a bottle’”), while managing to betray himself with both the brandy glass and savage irruptions of temper. There is a queer little scene in which Dick brings home a stack of artist’s materials with which it is hoped that his prospective father-in-law can kick-start his career: far from welcoming these attentions, the old man tells his daughter crossly not to “‘interfere.’” Calmed down and mollified, he continues to add extra layers to the persona he has created for himself. He is “‘an old Bohemian,’” he proudly declares, who has “‘cut society with a cut direct; I cut it when I was prosperous, and now I reap my reward and can cut it with dignity in my declension.’” To say that Van Tromp bears a faint resemblance to one or two of Thackeray’s broken-down old scamps—Costigan, say, in Pendennis—isn’t to ignore either the air of seedy menace or the bracing economy of the sketch. The reader guesses far more about Van Tromp than Stevenson ever tells him, and an unseen rake’s progress of squalid intrigues stretches out behind him into the Paris backstreets. His real origins probably lie in French literature, down amongst the blackmailers and backstairs wire-pullers of Balzac’s La Comédie humaine. Dickens, you feel, would have burlesqued Van Tromp into caricature. Stevenson has an instinctive understanding of the person he is, and the result—comic, self-engrossed, and infinitely sinister—is a wonderfully convincing portrait.

The Story of a Lie

Introduces the Admiral

When Dick Naseby was in Paris he made some odd acquaintances; for he was one of those who have ears to hear, and can use their eyes no less than their intelligence. He made as many thoughts as Stuart Mill; but his philosophy concerned flesh and blood, and was experimental as to its method. He was a type-hunter among mankind. He despised small game and insignificant personalities, whether in the shape of dukes or bagmen, letting them go by like sea-weed; but show him a refined or powerful face, let him hear a plangent or a penetrating voice, fish for him with a living look in some one’s eye, a passionate gesture, a meaning and ambiguous smile, and his mind was instantaneously awakened. ‘There was a man, there was a woman,’ he seemed to say, and he stood up to the task of comprehension with the delight of an artist in his art.

And indeed, rightly considered, this interest of his was an artistic interest. There is no science in the personal study of human nature. All comprehension is creation; the woman I love is somewhat of my handiwork; and the great lover, like the great painter, is he that can so embellish his subject as to make her more than human, whilst yet by a cunning art he has so based his apotheosis on the nature of the case that the woman can go on being a true woman, and give her character free play, and show littleness, or cherish spite, or be greedy of common pleasures, and he continue to worship without a thought of incongruity. To love a character is only the heroic way of understanding it. When we love, by some noble method of our own or some nobility of mien or nature in the other, we apprehend the loved one by what is noblest in ourselves. When we are merely studying an eccentricity, the method of our study is but a series of allowances. To begin to understand is to begin to sympathise; for comprehension comes only when we have stated another’s faults and virtues in terms of our own. Hence the proverbial toleration of artists for their own evil creations. Hence, too, it came about that Dick Naseby, a high-minded creature, and as scrupulous and brave a gentleman as you would want to meet, held in a sort of affection the various human creeping things whom he had met and studied.

One of these was Mr. Peter Van Tromp, an English-speaking, two-legged animal of the international genus, and by profession of general and more than equivocal utility. Years before he had been a painter of some standing in a colony, and portraits signed ‘Van Tromp’ had celebrated the greatness of colonial governors and judges. In those days he had been married, and driven his wife and infant daughter in a pony trap. What were the steps of his declension? No one exactly knew. Here he was at least, and had been any time these past ten years, a sort of dismal parasite upon the foreigner in Paris.

It would be hazardous to specify his exact industry. Coarsely followed, it would have merited a name grown somewhat unfamiliar to our ears. Followed as he followed it, with a skilful reticence, in a kind of social chiaroscuro, it was still possible for the polite to call him a professional painter. His lair was in the Grand Hotel and the gaudiest cafés. There he might be seen jotting off a sketch with an air of some inspiration; and he was always affable, and one of the easiest of men to fall in talk withal. A conversation usually ripened into a peculiar sort of intimacy, and it was extraordinary how many little services Van Tromp contrived to render in the course of six-and-thirty hours. He occupied a position between a friend and a courier, which made him worse than embarrassing to repay. But those whom he obliged could always buy one of his villainous little pictures, or, where the favours had been prolonged and more than usually delicate, might order and pay for a large canvas, with perfect certainty that they would hear no more of the transaction.

Among resident artists he enjoyed celebrity of a non-professional sort. He had spent more money—no less than three individual fortunes, it was whispered—than any of his associates could ever hope to gain. Apart from his colonial career, he had been to Greece in a brigantine with four brass carronades; he had travelled Europe in a chaise and four, drawing bridle at the palace-doors of German princes; queens of song and dance had followed him like sheep and paid his tailor’s bills. And to behold him now, seeking small loans with plaintive condescension, sponging for breakfast on an art-student of nineteen, a fallen Don Juan who had neglected to die at the propitious hour, had a colour of romance for young imaginations. His name and his bright past, seen through the prism of whispered gossip, had gained him the nickname of The Admiral.

Dick found him one day at the receipt of custom, rapidly painting a pair of hens and a cock in a little water-colour sketching box, and now and then glancing at the ceiling like a man who should seek inspiration from the muse. Dick thought it remarkable that a painter should choose to work over an absinthe in a public café, and looked the man over. The aged rakishness of his appearance was set off by a youthful costume; he had disreputable grey hair and a disreputable sore, red nose; but the coat and the gesture, the outworks of the man, were still designed for show. Dick came up to his table and inquired if he might look at what the gentleman was doing. No one was so delighted as the Admiral.

‘A bit of a thing,’ said he. ‘I just dash them off like that. I—I dash them off,’ he added with a gesture.

‘Quite so,’ said Dick, who was appalled by the feebleness of the production.

‘Understand me,’ continued Van Tromp; ‘I am a man of the world. And yet—once an artist always an artist. All of a sudden a thought takes me in the street; I become its prey: it’s like a pretty woman; no use to struggle; I must—dash it off.’

‘I see,’ said Dick.

‘Yes,’ pursued the painter; ‘it all comes easily, easily to me; it is not my business; it’s a pleasure. Life is my business—life—this great city, Paris—Paris after dark—its lights, its gardens, its odd corners. Aha!’ he cried, ‘to be young again! The heart is young, but the heels are leaden. A poor, mean business, to grow old! Nothing remains but the coup d’œil, the contemplative man’s enjoyment, Mr. —,’ and he paused for the name.

‘Naseby,’ returned Dick.

The other treated him at once to an exciting beverage, and expatiated on the pleasure of meeting a compatriot in a foreign land; to hear him, you would have thought they had encountered in Central Africa. Dick had never found any one take a fancy to him so readily, nor show it in an easier or less offensive manner. He seemed tickled with him as an elderly fellow about town might be tickled by a pleasant and witty lad; he indicated that he was no precision, but in his wildest times had never been such a blade as he thought Dick. Dick protested, but in vain. This manner of carrying an intimacy at the bayonet’s point was Van Tromp’s stock-in-trade. With an older man he insinuated himself; with youth he imposed himself, and in the same breath imposed an ideal on his victim, who saw that he must work up to it or lose the esteem of this old and vicious patron. And what young man can bear to lose a character for vice?

At last, as it grew towards dinner-time, ‘Do you know Paris?’ asked Van Tromp.

‘Not so well as you, I am convinced,’ said Dick.

‘And so am I,’ returned Van Tromp gaily. ‘Paris! My young friend—you will allow me?—when you know Paris as I do, you will have seen Strange Things. I say no more; all I say is, Strange Things. We are men of the world, you and I, and in Paris, in the heart of civilised existence. This is an opportunity, Mr. Naseby. Let us dine. Let me show you where to dine.’

Dick consented. On the way to dinner the Admiral showed him where to buy gloves, and made him buy them; where to buy cigars, and made him buy a vast store, some of which he obligingly accepted. At the restaurant he showed him what to order, with surprising consequences in the bill. What he made that night by his percentages it would be hard to estimate. And all the while Dick smilingly consented, understanding well that he was being done, but taking his losses in the pursuit of character as a hunter sacrifices his dogs. As for the Strange Things, the reader will be relieved to hear that they were no stranger than might have been expected, and he may find things quite as strange without the expense of a Van Tromp for guide. Yet he was a guide of no mean order, who made up for the poverty of what he had to show by a copious, imaginative commentary.

‘And such,’ said he, with a hiccup, ‘such is Paris.’

‘Pooh!’ said Dick, who was tired of the performance.

The Admiral hung an ear, and looked up sidelong with a glimmer of suspicion.

‘Good night,’ said Dick; ‘I’m tired.’

‘So English!’ cried Van Tromp, clutching him by the hand. ‘So English! So blasé! Such a charming companion! Let me see you home.’

‘Look here,’ returned Dick, ‘I have said good night, and now I’m going. You’re an amusing old boy: I like you, in a sense; but here’s an end of it for to-night. Not another cigar, not another grog, not another percentage out of me.’

‘I beg your pardon!’ cried the Admiral with dignity.

‘Tut, man!’ said Dick; ‘you’re not offended; you’re a man of the world, I thought. I’ve been studying you, and it’s over. Have I not paid for the lesson? Au revoir.’