0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

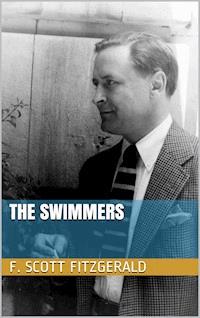

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American author of novels and short stories, whose works are the paradigmatic writings of the Jazz Age. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century. Fitzgerald is considered a member of the "Lost Generation" of the 1920s. He finished four novels: "This Side of Paradise", "The Beautiful and Damned", "The Great Gatsby" (his most famous), and "Tender Is the Night". A fifth, unfinished novel, "The Love of the Last Tycoon", was published posthumously. Fitzgerald also wrote many short stories that treat themes of youth and promise along with age and despair. Fitzgerald's work has been adapted into films many times. His short story, "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button", was the basis for a 2008 film. "Tender Is the Night" was filmed in 1962, and made into a television miniseries in 1985. "The Beautiful and Damned" was filmed in 1922 and 2010. "The Great Gatsby" has been the basis for numerous films of the same name, spanning nearly 90 years: 1926, 1949, 1974, 2000, and 2013 adaptations. In addition, Fitzgerald's own life from 1937 to 1940 was dramatized in 1958 in "Beloved Infidel".

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 33

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

I

In the Place Benoït, a suspended mass of gasoline exhaust cooked slowly by the June sun. It was a terrible thing, for, unlike pure heat, it held no promise of rural escape, but suggested only roads choked with the same foul asthma. In the offices of The Promissory Trust Company, Paris Branch, facing the square, an American man of thirty-five inhaled it, and it became the odor of the thing he must presently do. A black horror suddenly descended upon him, and he went up to the washroom, where he stood, trembling a little, just inside the door.

Through the washroom window his eyes fell upon a sign--1000 Chemises. The shirts in question filled the shop window, piled, cravated and stuffed, or else draped with shoddy grace on the show-case floor. 1000 Chemises--Count them! To the left he read Papeterie, Pâtisserie, Solde, Réclame, and Constance Talmadge in Déjeuner de Soleil; and his eye, escaping to the right, met yet more somber announcements: Vêtements Ecclésiastiques, Declaration de Décès, and Pompes Funèbres. Life and Death.

Henry Marston's trembling became a shaking; it would be pleasant if this were the end and nothing more need be done, he thought, and with a certain hope he sat down on a stool. But it is seldom really the end, and after a while, as he became too exhausted to care, the shaking stopped and he was better. Going downstairs, looking as alert and self-possessed as any other officer of the bank, he spoke to two clients he knew, and set his face grimly toward noon.

"Well, Henry Clay Marston!" A handsome old man shook hands with him and took the chair beside his desk.

"Henry, I want to see you in regard to what we talked about the other night. How about lunch? In that green little place with all the trees."

"Not lunch, Judge Waterbury; I've got an engagement."

"I'll talk now, then; because I'm leaving this afternoon. What do these plutocrats give you for looking important around here?"

Henry Marston knew what was coming.

"Ten thousand and certain expense money," he answered.

"How would you like to come back to Richmond at about double that? You've been over here eight years and you don't know the opportunities you're missing. Why both my boys--"

Henry listened appreciatively, but this morning he couldn't concentrate on the matter. He spoke vaguely about being able to live more comfortably in Paris and restrained himself from stating his frank opinion upon existence at home.

Judge Waterbury beckoned to a tall, pale man who stood at the mail desk.

"This is Mr. Wiese," he said. "Mr. Wiese's from downstate; he's a halfway partner of mine."

"Glad to meet you, suh." Mr. Wiese's voice was rather too deliberately Southern. "Understand the judge is makin' you a proposition."

"Yes," Henry answered briefly. He recognized and detested the type--the prosperous sweater, presumably evolved from a cross between carpetbagger and poor white. When Wiese moved away, the judge said almost apologetically:

"He's one of the richest men in the South, Henry." Then, after a pause: "Come home, boy."

"I'll think it over, judge." For a moment the gray and ruddy head seemed so kind; then it faded back into something one-dimensional, machine-finished, blandly and bleakly un-European. Henry Marston respected that open kindness--in the bank he touched it with daily appreciation, as a curator in a museum might touch a precious object removed in time and space; but there was no help in it for him; the questions which Henry Marston's life propounded could be answered only in France. His seven generations of Virginia ancestors were definitely behind him every day at noon when he turned home.

Home was a fine high-ceiling apartment hewn from the palace of a Renaissance cardinal in the Rue Monsieur--the sort of thing Henry could not have afforded in America. Choupette, with something more than the rigid traditionalism of a French bourgeois taste, had made it beautiful, and moved through gracefully with their children. She was a frail Latin blonde with fine large features and vividly sad French eyes that had first fascinated Henry in a Grenoblepensionin 1918. The two boys took their looks from Henry, voted the handsomest man at the University of Virginia a few years before the war.