0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

A powerful story of grace from the pen of Grace Livingston Hill. Star athlete, student, and fraternity president, Paul Courtland watches while a college classmate falls to an untimely death. Struck by his own part in the tragedy, he seeks solace in the classmate's peaceful room-and in the faith he has discovered. A friend introduces him to a young woman who is certain to bring him out of his somber mood - and into trouble. After yet another tragedy, Paul must choose: to follow his emotions or his faith. Will his choice even matter to those around him?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

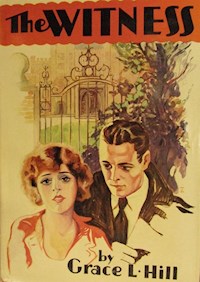

The Witness

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1917

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

TO MY MOTHER Marcia Macdonald Livingston

WHOSE HELPFUL CRITICISM AND LOVING ENCOURAGEMENT HAVE BEEN WITH ME THROUGH THE YEARS

"He that believeth on the Son of God hath the witness in himself." —I John 5:10

THE WITNESS

CHAPTER I

Like a sudden cloudburst the dormitory had gone into a frenzy of sound. Doors slammed, feet trampled, hoarse voices reverberated, heavy bodies flung themselves along the corridor, the very electrics trembled with the cataclysm. One moment all was quiet with a contented after-dinner-peace-before-study hours; the next it was as if all the forces of the earth had broken forth.

Paul Courtland stepped to his door and threw it back.

"Come on, Court, see the fun!" called the football half-back, who was slopping along with two dripping fire-buckets of water.

"What's doing?"

"Swearing-match! Going to make Little Stevie cuss! Better get in on it. Some fight! Tennelly sent 'Whisk' for a whole basket of superannuated cackle-berries"—he motioned back to a freshman bearing a basket of ancient eggs—"we're going to blindfold Steve and put oysters down his back, and then finish up with the fire-hose. Oh, the seven plagues of Egypt aren't in it with what we're going to do; and when we get done if Little Stevie don't let out a string of good, honest cuss-words like a man then I'll eat my hat. Little Stevie's got good stuff in him if it can only be brought out. We're a-going to bring it out. Then we're going to celebrate by taking him over to the theater and making him see 'The Scarlet Woman.' It'll be a little old miracle, all right, if he has any of his whining Puritanical ideas left in him after we get through with him. Come on! Get on the job!"

Drifting along with the surging tide of students, Courtland sauntered down the corridor to the door at the extreme end where roomed the victim.

He rather liked Stephen Marshall. There was good stuff in him; all the fellows recognized that. Only he was woefully unsophisticated, abnormally innocent, frankly religious, and a little too openly white in his life. It seemed a rebuke to the other fellows, unconscious though it might be. He felt with the rest that the fellow needed a lesson. Especially since the bald way in which he had dared to stand up for the old-fashioned view of miracles in biblical-lit. class that morning. Of course an ignorance like that wouldn't go down, and it was best he should learn it at once and get to be a good fellow without loss of time. A little gentle rubbing off of the "mamma's-good-little-boy" veneering would do him good. He wasn't sure but with such a course Marshall might even be eligible for the frat. that year. He sauntered along with his hands in his pockets; a handsome, capable, powerful figure; not taking any part in the preparations, but mildly interested in the plans. His presence lent enthusiasm to the gathering. He was high in authority. A star athlete, an A student, president of his fraternity, having made the Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year, and now in his senior year being chairman of the student exec. There would be no trouble with the authorities of the college if Court was along to give countenance.

Courtland stood opposite the end door when it was unceremoniously thrust open and the hilarious mob rushed in. From his position with his back against the wall he could see Stephen lift his fine head from his book and rise to greet them. There was surprise and a smile of welcome on his face. Courtland thought it almost a pity to reward such open-heartedness as they were about to do; but such things were necessary in the making of men. He watched developments with interest.

A couple of belated participants in the fray arrived breathlessly, shedding their mackinaws as they ran, and casting them down at Courtland's feet.

"Look after those, will you, Court? We've got to get in on this," shouted one as he thrust a noisy bit of flannel head-gear at Courtland.

Courtland gave the garments a kick behind him and stood watching.

There was a moment's tense silence while they told the victim what they had come for, and while the light of welcome in Stephen Marshall's eyes melted and changed into lightning. A dart of it went with a searching gleam out into the hall, and seemed to recognize Courtland as he stood idly smiling, watching the proceedings. Then the lightning was withheld in the gray eyes, and Marshall seemed to conclude that, after all, the affair must be a huge kind of joke, seeing Courtland was out there. Courtland had been friendly. He must not let his temper rise. The kindly light came into the eyes again, and for an instant Marshall almost disarmed the boldest of them with his brilliant smile. He would be game as far as he understood. That was plain. It was equally plain that he did not understand yet what was expected of him.

Pat McCluny, thick of neck, brutal of jaw, low-browed, red of face, blunt of speech, the finest, most unmerciful tackler on the football team, stepped up to Stephen and said a few words in a low tone. Courtland could not hear what they were save that they ended with an oath, the choicest of Pat McCluny's choice collection.

Instantly Stephen Marshall drew himself back, and up to his great height, lightning and thunder-clouds in his gray eyes, his powerful arms folded, his fine head crowned with its wealth of beautiful gold hair thrown a trifle back and up, his lips shut in a thin, firm line, his whole attitude that of the fighter; but he did not speak. He only looked from one to another of the wild young mob, searching for a friend; and, finding none, he stood firm, defying them all. There was something splendid in his bearing that sent a thrill of admiration down Courtland's spine as he watched, his habitual half-cynical smile of amusement still lying unconsciously about his lips, while a new respect for the country student was being born in his heart.

Pat, with a half-lowering of his bullet head, and a twisting of his ugly jaw, came a step nearer and spoke again, a low word with a rumble like the menace of a bull or a storm about to break.

With a sudden unexpected movement Stephen's arm shot forth and struck the fellow in the jaw, reeling him half across the room into the crowd.

With a snarl like a stung animal Pat recovered himself and rushed at Stephen, hurling himself with a stream of oaths, and calling curses down upon himself if he did not make Stephen utter worse before he was done with him. Pat was the "man" who was in college for football. It took the united efforts of his classmates, his frat., and the faculty to keep his studies within decent hailing distance of eligibility for playing. He came from a race of bullies whose culture was all in their fists.

Pat went straight for the throat of his victim. His fighting blood was up and he was mad clear down to the bone. Nobody could give him a blow like that in the presence of others and not suffer for it. What had started as a joke had now become real with Pat; and the frenzy of his own madness quickly spread to those daring spirits who were about him and who disliked Stephen for his strength of character.

They clinched, and Stephen, fresh from his father's remote Western farm, matched his mighty, untaught strength against the trained bully of a city street.

For a moment there was dead silence while the crowd in breathless astonishment watched and held in check their own eagerness. Then the mob spirit broke forth as some one called out:

"Pray for a miracle, Stevie! Pray for a miracle! You'll need it, old boy!"

The mad spirit which had incited them to the reckless fray broke forth anew and a medley of shouts arose.

"Jump in, boys! Now's the time!"

"Give him a cowardly egg or two—the kind that hits and runs!"

"Teach him that we will be obeyed!"

The latter came as a sort of chant, and was reiterated at intervals through the pandemonium of sound.

The fight raged on for minutes more, and still Stephen stood with his back against the wall, fighting, gasping, struggling, but bravely facing them all; a disheveled object with rotten eggs streaming from his face and hair, his clothes plastered with offensive yolks. Pat had him by the throat, but still he stood and fought as best he could.

Some one seized the bucket of water and deluged both. Some one else shouted, "Get the hose!" and more fellows tore off their coats and threw them down at Courtland's feet; some one tore Pat away, and the great fire-hose was turned upon the victim.

Gasping at last, and all but unconscious, he was set upon his feet, and harried back to life again. Over-powered by numbers, he could do nothing, and the petty torments that were applied amid a round of ringing laughter seemed unlimited; but still he stood, a man among them, his lips closed, a firm set about his jaw that showed their labor was in vain so far as making him obey their command was concerned. Not one word had he uttered since they entered his room.

"You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink," shouted one onlooker. "Cut it out, fellows! It's no use! You can't set him cussing. He never learned how. He could easier lead in prayer. You have to teach him how. Better cut it out!"

More tortures were applied, but still the victim was silent. The hose had washed him clean again, and his face shone white from the drenching. Some one suggested it was getting late and the show would begin. Some one else suggested they must dress up Little Stevie for his first play. There was a mad rush for garments. Any garments, no matter whose. A pair of sporty trousers, socks of brilliant colors—not mates, an old football shoe on one foot, a dancing-pump on the other, a white vest and a swallow-tail put on backward, collar and tie also backward, a large pair of white-cotton gloves commonly used by workmen for rough work—Johnson, who earned his way in college by tending furnaces, furnished these. Stephen bore it all, grim, unflinching, until they set him up before his mirror and let him see himself, completing the costume by a high silk hat crammed down upon his wet curls. He looked at the guy he was and suddenly he turned upon them and smiled, his broad, merry smile! After all that he could see the joke and smile! He never opened his lips nor spoke—just smiled.

"He's a pretty good guy! He's game, all right!" murmured some one in Courtland's ear. And then, half shamedly, they caught him high upon their shoulders and bore him down the stairs and out the door.

The theater was some distance off. They bore down upon a trolley-car and took a wild possession. They sang their songs and yelled themselves hoarse. People turned and watched and smiled, setting this down as one more prank of those university fellows.

They swarmed into the theater, with Stephen in their midst, and took noisy occupancy. Opera-glasses were turned their way, and the girls nudged one another and talked about the man in the middle with the queer garments.

The persecutions had by no means ceased because they had landed their victim in a public place. They made him ridiculous at every breath. They took off his hat, arranged his collar, and smoothed his hair as if he were a baby. They wiped his nose with many a flourishing handkerchief, and pointed out objects of interest about the theater in open derision of his supposed ignorance, to the growing amusement of those of the audience who were their neighbors. And when the curtain rose on the most notoriously flagrant play the city boasted, they added to its flagrance by their whispered explanations and remarks.

Stephen, in his ridiculous garb, sat in their midst, a prisoner, and watched the play he would not have chosen to see; watched it with a face of growing indignation; a face so speaking in its righteous wrath that those about who saw him turned to look again, and somehow felt condemned for being there.

Sometimes a wave of anger would sweep over the young man, and he would turn to look about him with an impulse to suddenly break away and attempt to defy them all. But his every movement was anticipated, and he had the whole football team about him! There was no chance to move. He must stay it through, much as he disliked it. He must stand it in spite of the tumult of rage in his heart. He was not smiling now. His face had that set, grim look of the faithful soldier taken prisoner and tortured to give information about his army's plans. Stephen's eyes shone true, and his lips were set firmly together.

"Just one nice little cuss-word and we'll take you home," whispered a tormentor. "A single little word will do, just to show you are a man."

Stephen's face was gray with determination. His yellow hair shone like a halo about his head. They had taken off his hat and he sat with his arms folded fiercely across the back of "Andy" Roberts's nifty evening coat.

"Just one little real cuss to show you are a man," sneered the freshman.

But suddenly a smothered cry arose. A breath of fear stirred through the house. The smell of smoke swept in from a sudden open door. The actors paused, grew white, and swerved in their places; then one by one fled out of the scene. The audience arose and turned to panic, even as a flame swept up and licked the very curtain while it fell.

All was confusion!

The football team, trained to meet emergencies, forgot their cruel play and scattered, over seats and railing, everywhere, to fire-escapes and doorways, taking command of wild, stampeding people, showing their training and their courage.

Stephen, thus suddenly set free, glanced about him, and saw a few feet away an open door, felt the fresh breeze of evening upon his hot forehead, and knew the upper back fire-escape was close at hand. By some strange whim of a panic-maddened crowd but few had discovered this exit, high above the seats in the balcony; for all had rushed below and were struggling in a wild, frantic mass, trampling one another underfoot in a mad struggle to reach the doorways. The flames were sweeping over the platform now, licking out into the very pit of the theater, and people were terrified. Stephen saw in an instant that the upper door, being farthest away from the center of the fire, was the place of greatest safety. With one frantic leap he gained the aisle, strode up to the doorway, glanced out into the night to take in the situation; cool, calm, quiet, with the still stars overhead, down below the open iron stairway of the fire-escape, and a darkened street with people like tiny puppets moving on their way. Then turning back, he tore off the grotesque coat and vest, the confining collar, and threw them from him. He plunged down the steps of the aisle to the railing of the gallery, and, leaning there in his shirt-sleeves and the queer striped trousers, he put his hands like a megaphone about his lips and shouted:

"Look up! Look up! There is a way to escape up here! Look up!"

Some poor struggling ones heard him and looked up. A little girl was held up by her father to the strong arms reached out from the low front of the balcony. Stephen caught her and swung her up beside him, pointing her up to the door, and shouting to her to go quickly down the fire-escape, even while he reached out his other hand to catch a woman, whom willing hands below were lifting up. Men climbed upon the seats and vaulted up when they heard the cry and saw the way of safety; and some stayed and worked bravely beside Stephen, wrenching up the seats and piling them for a ladder to help the women up. More just clambered up and fled to the fire-escape, out into the night and safety.

But Stephen had no thought of flight. He stayed where he was, with aching back, cracking muscles, sweat-grimed brow, and worked, his breath coming in quick, sharp gasps as he frantically helped man, woman, child, one after another, like sheep huddling over a flood.

Courtland was there.

He had lingered a moment behind the rest in the corner of the dormitory corridor, glancing into the disfigured room; water, egg-shells, ruin, disorder everywhere! A little object on the floor, a picture in a cheap oval metal frame, caught his eye. Something told him it was the picture of Stephen Marshall's mother that he had seen upon the student's desk a few days before, when he had sauntered in to look the new man over. Something unexplained made him step in across the water and debris and pick it up. It was the picture, still unscarred, but with a great streak of rotten egg across the plain, placid features. He recalled the tone in which the son had pointed out the picture and said, "That's my mother!" and again he followed an impulse and wiped off the smear, setting the picture high on the shelf, where it looked down upon the depredation like some hallowed saint above a carnage.

Then Courtland sauntered on to his room, completed his toilet, and followed to the theater. He had not wanted to get mixed up too much in the affair. He thought the fellows were going a little too far with a good thing, perhaps. He wanted to see it through, but still he would not quite mix with it. He found a seat where he could watch what was going on without being actually a part of it. If anything should come to the ears of the faculty he wanted to be on the side of conservatism always. That Pat McCluny was not just his sort, though he was good fun. But he always put things on a lower level than college fellows should go. Besides, if things went too far a word from himself would check them.

Courtland was rather bored with the play, and was almost on the point of going back to study when the cry arose and panic followed.

Courtland was no coward. He tore off his handsome overcoat and rushed to meet the emergency. On the opposite side of the gallery, high up by another fire-escape he rendered efficient assistance to many.

The fire was gaining in the pit; and still there were people down there, swarms of them, struggling, crying, lifting piteous hands for assistance. Still Stephen Marshall reached from the gallery and pulled up, one after another, poor creatures, and still the helpless thronged and cried for aid.

Dizzy, blinded, his eyes filled with smoke, his muscles trembling with the terrible strain, he stood at his post. The minutes seemed interminable hours, and still he worked, with heart pumping painfully, and mind that seemed to have no thought save to reach down for another and another, and point up to safety.

Then, into the midst of the confusion there arose an instant of great and awful silence. One of those silences that come even into great sound and claim attention from the most absorbed.

Paul Courtland, high in his chosen station, working eagerly, successfully, calmly, looked down to see the cause of this sudden arresting of the universe; and there, below, was the pit full of flame, with people struggling and disappearing into fiery depths below. Just above the pit stood Stephen, lifting aloft a little child with frightened eyes and long streaming curls. He swung him high and turned to stoop again; then with his stooping came the crash; the rending, grinding, groaning, twisting of all that held those great galleries in place, as the fire licked hold of their supports and wrenched them out of position.

One instant Stephen was standing by that crimson-velvet railing, with his lifted hand pointing the way to safety for the child, the flaming fire lighting his face with glory, his hair a halo about his head, and in the next instant, even as his hand was held out to save another, the gallery fell, crashing into the fiery, burning furnace! And Stephen, with his face shining like an angel's, went down and disappeared with the rest, while the consuming fire swept up and covered them.

Paul Courtland closed his eyes on the scene, and caught hold of the door by which he stood. He did not realize that he was standing on a tiny ledge, all that was left him of footing, high, alone, above that burning pit where his fellow-student had gone down; nor that he had escaped as by a miracle. There he stood and turned away his face, sick and dizzy with the sight, blinded by the dazzling flames, shut in to that tiny spot by a sudden wall of smoke that swept in about him. Yet in all the danger and the horror the only thought that came was, "God! That was a man!"

CHAPTER II

Paul Courtland never knew how he had been saved from that perilous position high up on a ledge in the top of the theater, with the burning, fiery furnace below him. Whether his senses came back sufficiently to guide him along the narrow footing that was left, to the door of the fire-escape, where some one rescued him, or whether a friendly hand risked all and reached out to draw him to safety.

He only knew that back there in that blank daze of suspended time, before he grew to recognize the whiteness of the hospital walls and the rattle of the nurse's starched skirt along the corridor, there was a long period when he was shut in with four high walls of smoke. Smoke that reached to heaven, roofing him away from it, and had its foundations down in the burning fiery pit of hell where he could hear lost souls struggling with smothered cries for help. Smoke that filled his throat, eyes, brain, soul. Terrible, enfolding, imprisoning smoke; thick, yellow, gray, menacing! Smoke that shut his soul away from all the universe, as if he had been suddenly blotted out, and made him feel how stark alone he had been born, and always would be evermore.

He seemed to have lain within those slowly approaching walls of smoke a century or two ere he became aware that he was not alone, after all. There was a Presence there beside him. Light, and a Presence! Blinding light. He reasoned that other men, the men outside of the walls of smoke, the firemen perhaps, and by-standers, might think that light came from the fire down in the pit, but he knew it did not. It radiated from the Presence beside him. And there was a Voice, calling his name. He seemed to have heard the call years back in his life somewhere. There was something about it, too, that made his heart leap in answer, and brought that strange thrill he used to have as a boy in prep. school, when his captain called him into the game, though he was only a substitute.

He could not look up, yet he could see the face of the Presence now. What was there so strangely familiar, as if he had been looking upon that face but a few moments before? He knew. It was that brave spirit come back from the pit. Come, perhaps, to lead him out of this daze of smoke and darkness. He spoke, and his own voice sounded glad and ringing:

"I know you now. You are Stephen Marshall. You were in college. You were down there in the theater just now, saving men."

"Yes, I was in college," the Voice spoke, "and I was down there just now, saving men. But I am not Stephen Marshall. Look again."

And suddenly he understood.

"Then you are Stephen Marshall's Christ! The Christ he spoke of in the class that day!"

"Yes, I am Stephen Marshall's Christ. He let me live in Him. I am the Christ you sneered at and disbelieved!"

He looked and his heart was stricken with shame.

"I did not understand. It was against reason. But had not seen you then."

"And now?"

"Now? What do you want of me?"

"You shall be shown."

The smoke ebbed low and swung away his consciousness, and even the place grew dim about him, but the Presence was there. Always through suspended space as he was borne along, and after, when the smoke gave way, and air, blessed air, was wafted in, there was the Presence. If it had not been for that he could not have borne the awfulness of nothing that surrounded him. Always there was the Presence!

There was a bandage over his eyes for days; people speaking in whispers; and when the bandage was taken away there were the white hospital walls, so like the walls of smoke at first in the dim light, high above him. When he had grown to understand it was but hospital walls, he looked around for the Presence in alarm, crying out, "Where is He?"

Bill Ward and Tennelly and Pat were there, huddled in a group by the door, hoping he might recognize them.

"He's calling for Steve!" whispered Pat, and turned with a gulp while the tears rolled down his cheeks. "He must have seen him go!"

The nurse laid him down on the pillow again, replacing the bandage. When he closed his eyes the Presence came back, blessed, sweet—and he was at peace.

The days passed; strength crept back into his body, consciousness to his brain. The bandage was taken off once more, and he saw the nurse and other faces. He did not look again for the Presence. He had come to understand he could not see it with his eyes; but always it was there, waiting, something sweet and wonderful. Waiting to show him what to do when he was well.

The memorial services had been held for Stephen Marshall many days, the university had been draped in black, with its flag at half-mast, the proper time, and its mourning folded away, ere Paul Courtland was able to return to his room and his classes.

They welcomed him back with touching eagerness. They tried to hush their voices and temper their noisiness to suit an invalid. They told him all their news, what games had been won, who had made Phi Beta Kappa, and what had happened at the frat. meetings. But they spoke not at all of Stephen!

Down the hall Stephen's door stood always open, and Courtland, walking that way one day, found fresh flowers upon his desk and wreathed around his mother's picture. A quaint little photograph of Stephen taken several years back hung on one wall. It had been sent at the class's request by Stephen's mother to honor her son's chosen college.

The room was set in order, Stephen's books were on the shelves, his few college treasures tacked up about the walls; and conspicuous between the windows hung framed the resolutions concerning Stephen the hero-martyr of the class, telling briefly how he had died, and giving him this tribute, "He was a man!"

Below the resolutions, on the little table covered with an old-fashioned crocheted cotton table-cover, lay Stephen's Bible, worn, marked, soft with use. His mother had wished it to remain. Only his clothes had been sent back to her who had sent him forth to prepare for his life-work, and received word in her distant home that his life-work had been already swiftly accomplished.

Courtland entered the room and looked around.

There were no traces of the fray that had marred the place when last he saw it. Everything was clean and fine and orderly. The simple saint-like face of the plain farmer's-wife-mother looked down upon it all with peace and resignation. This life was not all. There was another. Her eyes said that. Paul Courtland stood a long time gazing into them.

Then he closed the door and knelt by the little table, laying his forehead reverently upon the Bible.

Since he had returned to college and things of life had become more real, Reason had returned to her throne and was crying out against his "fancies." What was that experience in the hospital but the phantasy of a sick brain? What was the Presence but a fevered imagination? He had been growing ashamed of dwelling upon the thought, ashamed of liking to feel that the Presence was near when he was falling asleep at night. Most of all he had felt a shame and a land of perplexity in the biblical-literature class where he faced "FACTS" as the professor called them, spoken in capitals. Science was another force which mocked his fancies. Philosophy cooled his mind and wakened him from his dreams. In this atmosphere he was beginning to think that he had been delirious, and was gradually returning to his normal state, albeit with a restless dissatisfaction he had never known before.

But now in this calm, rose-decked room, with the quiet eyes of the simple mother looking down upon him, the resolutions in their chaplet-of-palm framing, the age-old Bible thumbed and beloved, he knew he had been wrong. He knew he would never be the same. That Presence, Whoever, Whatever it was, had entered into his life. He could never forget it; never be convinced that it was not; never be entirely satisfied without it! He believed it was the Christ! Stephen Marshall's Christ!

By and by he lifted up his head and opened the little worn Bible, reverently, curiously, just to touch it and think how the other boy had done. The soft, much-turned leaves fell open of themselves to a heavily marked verse. There were many marked verses all through the book.

Courtland's eyes followed the words:

He that believeth on the Son of God hath the witness in himself.

Could it be that this strange new sense of the Presence was "the witness" here mentioned? He knew it like his sense of rhythm, or the look of his mother's face, or the joy of a summer morning. It was not anything he could analyze. One might argue that there was no such thing, science might prove there was not, but he knew it, had seen it, felt it! He had the witness in himself. Was that what it meant?

With troubled brow he turned over the leaves again:

If any man will do his will, he shall know of the doctrine, whether it be of God.

Ah! There was an offer, why not close with it?

He dropped his head on the open book with the old words of self-surrender:

"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

A moment later Pat McCluny opened the door, cautiously, quietly; then, with a nod to Tennelly back of him, he entered with confidence.

Courtland rose. His face was white, but there was a light of something in his eyes they did not understand.

They went over to him as if he had been a child who had been lost and was found on some perilous height and needing to be coaxed gently away from it.

"Oh, so you're here, Court," said Tennelly, slapping his shoulder with gentle roughness, "Great little old room, isn't it? The fellows' idea to keep flowers here. Kind of a continual memorial."

"Great fellow, that Steve!" said Pat, hoarsely. He could not yet speak lightly of the hero-martyr whom he had helped to send to his fiery grave.

But Courtland stood calmly, almost as if he had not heard them. "Pat, Nelly," he said, turning from one to the other gravely, "I want to tell you fellows that I have met Steve's Christ and after this I stand for Him!"

They looked at him curiously, pityingly. They spoke with soothing words and humored him. They led him away to his room and left him to rest. Then they walked with solemn faces and dejected air into Bill Ward's room and threw themselves down upon his couch.

"Where's Court?" Bill looked up from the theme he was writing.

"We found him in Steve's room," said Tennelly, gloomily, and shook his head.

"It's a deuced shame!" burst forth Pat. (He had cut out swearing for a time.) "He's batty in the bean!"

Tennelly answered the shocked question in the eyes of Bill with a nod. "Yes, the brightest fellow in the class, but he sure is batty in the bean! You ought to have heard him talk. Say! I don't believe it was all the fire. Court's been studying too hard. He's been an awful shark for a fellow that went in for athletics and everything else. He's studied too hard and it's gone to his head!"

Tennelly sat gloomily staring across the room. It was the old cry of the man who cannot understand.

"He needs a little change," said Bill, putting his feet up on the table comfortably and lighting a cigarette. "Pity the frat. dance is over. He needs to get him a girl. Be a great stunt if he'd fall for some jolly girl. Say! I'll tell you what. I'll get Gila after him."

"Who's Gila?" asked Tennelly, gloomily. "He won't notice her any more than a fly on the wall. You know how he is about girls."

"Gila's my cousin. Gila Dare. She's a good sport, and she's a winner every time. We'll put Gila on the job. I've got a date with her to-morrow night and I'll put her wise. She'll just enjoy that kind of thing. He's met her, too, over at the Navy game. Leave it to Gila."

"What style is she?" asked Tennelly, still skeptical.

"Oh, tiny and stylish and striking, with big eyes. A perfect little peach of an actress."

"Court's too keen for acting. He'll see through her in half a second. She can't put one over on Court."

"She won't try," said the ardent cousin. "She'll just be as innocent. They'll be chums in half an hour, or it'll be the first failure for Gila."

"Well, if any girl can put one over on Court, I'll eat my hat; but it's worth trying, for if Court keeps on like this we'll all be buying prayer-books and singing psalms before another semester."

"You'll eat your hat, all right," said Bill Ward, rising in his wrath. "Nelly, my infant, I tell you Gila never fails. If she gets on the job Court'll be dead in love with her before the midwinter exams.!"

"I'll believe it when I see it," said Tennelly, rising.

"All right," said Bill. "Remember you're in for a banquet during vacation. Fricaseed hat the pièce de resistance!"

CHAPTER III

It was a sumptuous library in which Gila Dare awaited the coming of Paul Courtland.

Great, deep, red-leather chairs stood everywhere invitingly, the floor was spread with a magnificent specimen of Royal Bokhara, the rich recesses of the noble walls were lined with books in rare editions, a heavily carved table of dull black wood from some foreign land sprawled in the center of the room and held a great bronze lamp of curious pattern, bearing a ruby light. Ornate bronzes lurked on pedestals in shadows, unexpectedly, and caught the eye alarmingly, like grim ones set to watch. A throbbing fire like the heart of a lit ruby burned in a massive fireplace of grotesque tiles, as though it were the opening into great depths of unquenchable fire to which this room might be but an approach.

Gila herself, slight, dark-eyed, with pearl-white skin and dusky hair, was dressed in crimson velvet, soft and clinging like chiffon, catching the light and shimmering it with strange effect. The dark hair was curiously arranged, and stabbed just above her ears with two dagger-like combs flashing with jewels. A single jewel burned at her throat on an invisible chain, and jewels flashed from the little pointed crimson-satin slippers, setting off the slim ankles in their crimson-silk covering. The whole effect was startling. One wondered why she had chosen so elaborate a costume to waste upon a single college student.

She stood with one dainty foot poised on the brass trappings of the hearth. In her short skirts she seemed almost a child; so sweet the droop of the pretty lips; so innocent the dark eyes as they looked into the fire; so soft the shadows that played in the dark hair! And yet, as she turned to listen for a step in the hall, there was something gleaming, sinister, in those dark eyes, something mocking in the red lips. She might have been a daughter of Satan as she stood, the firelight picking out those jeweled horns and slippers.

"Leave him to me," she had said to her cousin when he told her how the brilliant young athlete and intellectual star of the university had been stung by the religious bug. "Send him to me. I'll take it out of him and he'll never know it's gone."

Paul Courtland entered, unsuspecting. He had met Gila a number of times before, at college dances and the games. He was not exactly flattered, but decidedly pleased that she had sent for him. Her brightness and seeming innocence had attracted him strongly.

The contrast from the hall with its blaze of electrics to the lurid light of the library affected him strangely. He paused on the threshold and passed his hand over his eyes. Gila stood where the ruby light of hearth and lamp would set her vivid dress on fire and light the jewels at her throat and hair. She knew her clear skin, dark hair, and eyes would bear the startling contrast, and how her white shoulders gleamed from the crimson velvet. She knew how to arrange the flaming scarf of gauze deftly about those white shoulders so that it would reveal more than it concealed.

The young man lingered unaccountably. He had a sense of leaving something behind him. Almost he hesitated as she came forward to greet him, and looked back as if to rid himself of some obligation. Then she put her bits of confiding hands out to him and smiled that wistful, engaging smile that would have been worth a fortune on the screen.

He thrilled with wonder over her delicate, dazzling beauty; and felt the luxury of the room about him, responding to its lure.

"So dandy of you to come to me when you are so busy after your long illness." Her voice was soft and confiding, its cadences like soothing music. She motioned him to a chair. "You see, I wanted to have you all to myself for a little while, just to tell you how perfectly fine you were at that awful fire."

She dropped upon the couch drawn out at just the right angle from the fire and settled among the cushions gracefully. The flicker of the firelight played upon the jeweled combs and gleamed at her throat. The little pointed slippers cozily crossed looked innocent enough to have been meant for the golden street. Her eyes looked up into his with that confiding lure that thrills and thrills again.

Her voice dropped softer, and she turned half away and gazed pensively into the fire on the hearth. "I wouldn't let them talk to me about it. It seemed so awful. And you were so strong and great."

"It was nothing!" He did not want to talk about the fire. There was something incongruous, almost unholy, in having it discussed here. It jangled on his nerves. For there in front of him in the fireplace burned a mimic pit like the one into which the martyr Steve had fallen; and there before him on the couch sat the girl! What was there so familiar about her? Ah! now he knew. The Scarlet Woman! Her gown was an exact reproduction of the one the great actress had worn on the stage that night. He was conscious of wishing to sit beside her on that couch and revel in the ravishing color of her. What was there about this room that made all his pulses beat?

Playfully, skilfully, she led him on. They talked of the dances and games, little gossip of the university, with now and then a telling personality, and a sweep of long lashes over pearly cheeks, or a lifting of great, innocent eyes of admiration to his face.

She offered wine in delicate gold-incrusted ruby glasses, but Courtland did not drink. He scarcely noticed her veiled annoyance at his refusal. He was drinking in the wine of her presence. She suggested that he smoke, and would not have hesitated to join him, perhaps, but he told her he was in training, and she cooed softly of his wonderful strength of character in resisting.

By this time he was in the coveted seat beside her on the couch, and the fire burned low and red. They had ceased to talk of games and dances. They were talking of each other, those intimate nothings that mean a breaking down of distance and a rapidly growing familiarity.

The young man was aware of the fascination of the small figure in her crimson robings, sitting so demurely in the firelight, the gauzy scarf dropped away from her white neck and shoulders, the lovely curve of her baby cheek and tempting neck showing against the background of the shadows behind her. He was aware of a distinct longing to take her in his arms and crush her to him, as he would pluck a red berry from a bank, and feel its stain upon his lips. Stain! A stain was a thing that was hard to remove. There were blood-stains sometimes and agonies; and yet men wanted to pluck the berries and feel the stain upon their lips!

He was not under the hallucination that he was suddenly falling in love with this girl. He did not name the passionate outcry in his soul love. He knew she had been a charmer of many, and in yielding himself to her recognized power he was for the moment playing with a force that was new and interesting, with which he had felt altogether strong enough to contend for an evening or he would not have come. That it should thrill along all his senses with this unreasoning rapture was most astonishing. He had never been a fellow to "fall" for every girl he met, and now he felt himself gradually yielding to the beautiful spell about him with a kind of wonder.

The lights and coloring of the room that had smote his senses unpleasantly when he first entered had thrown him now into a kind of delicious fever. The neglected wine sparkling dimly in the costly glasses seemed a part of it. He felt an impulse to reach out, seize a glass, and drain it. What if he should? What if he flung away his ideas and principles and let the moment sway him as it would, just for once? Why should he not try life as it presented itself?

These fancies fled through his brain like phantoms that did not dare to linger. His was no callow mind, ignorant of the world. He had thought and read and lived his ideas well for so young a man. He had vigorously protested against weakness of every kind; yet here he was feeling the drawing power of things he had always despised; reveling in the wine-red color of the room, in the pit-like glow of the fire; watching the play of smiles and wistfulness on the lovely face of the girl. He had often wondered what others saw so attractive in her beyond a pretty face. But now he understood. Her child-like speech and pretty little ways fascinated him. Perhaps she was really innocent of her own charms. Perhaps a man might lead her to give up certain of her ways that caused her to be criticized. What a woman she would be then! What a friend to have!

This was the last sop he threw to his conscience before he consciously began to yield to the spell that was upon him.

She had been speaking of palmistry, and she took his hand in hers, innocently, impersonally, with large eyes lifted inquiringly. Her breath was on his face; her touch had stirred his senses with a madness he had never felt nor measured in himself before.

"The life-line is here," she said, coolly, and traced it delicately along his palm with a sea-shell tinted finger. Like cool delicious fire it spread from nerve to nerve and set aside his reason in a frenzy. He would seize the berry and feel its stain upon his lips now no matter what!—

"Paul!"

It was as distinct upon his ear as if the words had been spoken; as startling and calming as a cool hand upon his fevered brow; the sudden entrance of a guest. He had seized her hands with sudden fervor, and now, almost in the same moment, flung them from him and stood up, a man in full possession of his senses. "Hark!" he said, and as he spoke a cry broke faintly forth above them, and there was sound of rushing feet. A frightened maid burst into the room unannounced.

"Oh, Miss Gila, I beg yer pardon, but Master Harry's got his father's razor, an' he's cut hisself something awful."

The maid was weeping and wringing her hands helplessly, but Gila stood frowning angrily. Courtland sprang up the stairs. In the tumult of his mind he would have rejoiced if the house had been on fire, or a cyclone had struck the place—anything so he could fling himself into service. He drew in long, deep breaths. It was like mountain air to get away from that lurid room into the light once more. A sense of lost power returned, was over him. The spell was broken.

He bent over the little boy alertly, grasped the wrist, and stopped the spurt of blood. The frightened child looked up into his face and stopped crying.

"You should have telephoned for the doctor at once and not made all this fuss in the presence of a guest," scolded Gila as she came up the stairs. She looked garish and out of place with her red velvet and jewels in the brilliant light of the white-tiled bathroom. She stood helplessly by the door, making no move to help Courtland. The maid was at the telephone, frantically calling for the family physician.

"Hand me those towels," commanded Courtland, and saw the look of disgust upon Gila's face as she reluctantly picked her way across the blood-stains. It struck him that they were the color of her frock. The stain of the crushed berry. He moistened his dry lips. At least the stain was not upon his lips. He had escaped. Yet by how narrow a margin.

The girl felt the man's changed attitude without in the least understanding it. She thought it had been the cry of the child that made him jump up and fling her hands from him with that sudden "Hark!" in the moment when he had almost yielded. She did not know that an inner voice had called him. She only knew that she had lost him for the time, and her vanity was still panting like a wild thing that has lost its prey.

He gathered the little boy into his arms when he had bound up the cut, and talked to him cheerfully. The child's curly head rested trustfully against the big shoulder.

"Floor all bluggy!" he remarked, languidly. "Wall all bluggy!" Then his eyes fell on his sister in her scarlet frock. "Gila all bluggy, too!" he laughed, and pointed with his well hand.

"Be still, Harry!" said Gila, sharply, and when Courtland looked up in wonder he saw the delicate brows drawn blackly, and the mouth had lost its innocent sweetness. The child shrank in his arms, and he put a reassuring hand upon the little head that snuggled comfortedly against his coat. It was one of Courtland's strong points, this love of little children. He grew fine and gentle in their presence. It often drew attention on the athletic field when some little fellow strayed his way and Courtland would turn to talk to the child. People would stop their conversation and look his way; and a whole grand stand would come to silence just to see him walk across the diamond with a little golden-haired kid upon his shoulder. There was something inexpressibly beautiful about his attitude toward a child.

Gila saw it now and wondered. What unexpected trait was this that sat upon the young man like a crown? Here, indeed, was a man who was worth cultivating, not merely for the caprice of the moment. There was something in his face and attitude now that commanded her respect and admiration; something that drew her as she had not been drawn before. She would win him now for his own sake, not just to show how she could charm away his morbid fancies.

She continued to stare at the young man with eyes that saw new things in him, while Courtland sat petting the child and telling him a story. He paid no further attention to her.

When Gila set her heart upon a thing she had always had it. This had been her father's method of bringing her up. Her mother was too busy with her clubs and her social functions to see the harm. And now Gila suddenly became aware that she was setting her heart upon this young man. The eternal feminine in her that was almost choked with selfishness was crying out for a man like this one to comfort and pet her the way he was comforting and petting her little brother. That he had not yielded too easily to her charms made him all the more desirable. The interruption had come so suddenly that she couldn't even be sure he had been about to take her hands in his when he flung them from him. He had sprung from the couch almost as if he had been under orders. She could not understand it, only she knew she was drawn by it all.

But he should yield! She had power and she would use it. She had beauty and it should wound him. She would win that gentle deference and attention for her own. In her jealous, spoiled, little heart she hated the little brother for lying there in his arms so, interrupting their evening just when she had him where she had wanted him. Whether she wanted him for more than a plaything she did not know, but her plaything he should be as long as she desired him—and more also if she chose.

When Courtland lifted his head at the sound of the doctor's footsteps on the stairs he saw the challenge in Gila's eyes. Drawn up against the white enamel of the bathroom door, all her brilliant velvet and jewels gleaming in the brightness of the room, her regal little head up, her chin lifted half haughtily, her innocent mouth pursed softly with determination, her eyes wide with an inscrutable look—something more than challenge—something soft, appealing, alluring, that stirred him and drew him and repelled him all in one.

With a sense of something stronger than he was back of him, he lifted his own chin and hardened his eyes in answering challenge. He did not know it, of course, but he wore the look that he always had when about to meet a foe in a game—a look of strength and concealed power that nearly always made the coming foe quake when he saw it.

He shrank from going back to that red room again, or from being alone with her; and when she would have had him return to the library he declined, urging studies and an examination on the morrow. She received his somewhat brusque reply with a hurt look, her mouth drooped grievedly, and her eyes took on a wide, child-like look of distress that gave an impression of innocence. He went away wondering if, after all, he had not misjudged her. Perhaps she was only an adorable child who had no idea of the effect her artlessness had upon men. She certainly was lovely—wonderful! And yet the last glimpse he had of her had left that impression of jeweled horns and scarlet, pointed toes. He had to get away and think it out calmly before he went again. Oh yes, he was going again. He had promised her at the last moment.

The sense of having escaped something fateful was passing already. The coolness of the night and the quiet of the starlight had calmed him. He thought he had been a fool not to have stayed a little longer when she asked him so prettily; and he must go soon again.

CHAPTER IV

"I think I'll go to church this morning, Nelly. Do you want to go along?" announced Courtland, the next morning.

Tennelly looked up aghast from the sporting page of the morning paper he was lazily reading.

"Go with him, Nelly, that's a good boy!" put in Bill Ward, agreeably, winking his off eye at Tennelly. "It'll do you good. I'd go with you, only I've got to get that condition made up or they'll fire me off the 'varsity, and I only need this one more game to get my letter."

"Go to thunder!" growled Tennelly. "What do you think I want to go to church for a morning like this? Court, you're crazy! Let's go and get two saddle-horses and ride in the park. It's a peach of a morning for a ride."

"I think I'll go to church," said Courtland, with his old voice of quiet decision. "Do you want to go or not?"