0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

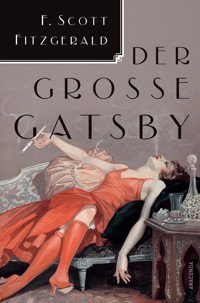

- Herausgeber: Arcadia Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This Side of Paradise is the debut novel of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Published in 1920, and taking its title from a line of the Rupert Brooke poem Tiare Tahiti, the book examines the lives and morality of post-World War I youth. Its protagonist, Amory Blaine, is an attractive Princeton University student who dabbles in literature. The novel explores the theme of love warped by greed and status-seeking.

This Side of Paradise was published on March 26, 1920 with a first printing of 3,000 copies. The initial printing sold out in three days. On March 30, four days after publication and one day after selling out the first printing, Fitzgerald wired for Zelda to come to New York and get married that weekend. Barely a week after publication, Zelda and Scott married in New York on April 3, 1920.

The book went through 12 printings in 1920 and 1921, for a total of 49,075 copies. The novel itself did not provide a huge income for Fitzgerald. Copies sold for $1.75 for which he earned 10 percent on the first 5,000 copies and 15 percent beyond that. In total, in 1920 he earned $6,200 from the book. Its success, however, helped the now-famous Fitzgerald earn much higher rates for his short stories.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

THE BOOK

This Side of Paradise is the debut novel of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Published in 1920, and taking its title from a line of the Rupert Brooke poem Tiare Tahiti, the book examines the lives and morality of post-World War I youth. Its protagonist, Amory Blaine, is an attractive Princeton University student who dabbles in literature. The novel explores the theme of love warped by greed and status-seeking.

This Side of Paradise was published on March 26, 1920 with a first printing of 3,000 copies. The initial printing sold out in three days. On March 30, four days after publication and one day after selling out the first printing, Fitzgerald wired for Zelda to come to New York and get married that weekend. Barely a week after publication, Zelda and Scott married in New York on April 3, 1920.

The book went through 12 printings in 1920 and 1921, for a total of 49,075 copies. The novel itself did not provide a huge income for Fitzgerald. Copies sold for $1.75 for which he earned 10 percent on the first 5,000 copies and 15 percent beyond that. In total, in 1920 he earned $6,200 from the book. Its success, however, helped the now-famous Fitzgerald earn much higher rates for his short stories.

(source wikiperdia.org)

THE AUTHOR

Born in 1896 in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to an upper-middle-class family, Fitzgerald was named after his famous second cousin, three times removed, Francis Scott Key, but was referred to by the familiar moniker Scott Fitzgerald. He was also named after his deceased sister, Louise Scott, one of two sisters who died shortly before his birth. "Well, three months before I was born," he wrote as an adult, "my mother lost her other two children ... I think I started then to be a writer." His parents were Mollie (McQuillan) and Edward Fitzgerald. His mother was of Irish descent, and his father had Irish and English ancestry.

Fitzgerald spent the first decade of his childhood primarily in Buffalo, New York (1898–1901 and 1903–1908, with a short interlude in Syracuse, New York between January 1901 and September 1903). His parents, both Catholic, sent Fitzgerald to two Catholic schools on the West Side of Buffalo, first Holy Angels Convent (1903–1904, now disused) and then Nardin Academy (1905–1908). His formative years in Buffalo revealed him to be a boy of unusual intelligence and drive with a keen early interest in literature, his doting mother ensuring that her son had all the advantages of an upper-middle-class upbringing. In a rather unconventional style of parenting, Fitzgerald attended Holy Angels with the peculiar arrangement that he go for only half a day—and was allowed to choose which half.

In 1908, his father was fired from Procter & Gamble, and the family returned to Minnesota, where Fitzgerald attended St. Paul Academy in St. Paul from 1908 to 1911. When he was 13 he saw his first piece of writing appear in print—a detective story published in the school newspaper. In 1911, when Fitzgerald was 15 years old, his parents sent him to the Newman School, a prestigious Catholic prep school in Hackensack, New Jersey. Fitzgerald played on the 1912 Newman football team. At Newman, he met Father Sigourney Fay, who noticed his incipient talent with the written word and encouraged him to pursue his literary ambitions.

After graduating from the Newman School in 1913, Fitzgerald decided to stay in New Jersey to continue his artistic development at Princeton University. Fitzgerald tried out for the college football team, but was cut the first day of practice. At Princeton, he firmly dedicated himself to honing his craft as a writer. There he became friends with future critics and writers Edmund Wilson (Class of 1916) and John Peale Bishop (Class of 1917), and wrote for the Princeton Triangle Club, the Nassau Lit, and the Princeton Tiger. He also was involved in the American Whig-Cliosophic Society, which ran the Nassau Lit. His absorption in the Triangle—a kind of musical-comedy society—led to his submission of a novel to Charles Scribner's Sons where the editor praised the writing but ultimately rejected the book. He was a member of the University Cottage Club, which still displays Fitzgerald's desk and writing materials in its library.

Fitzgerald's writing pursuits at Princeton came at the expense of his coursework. He was placed on academic probation, and in 1917 he dropped out of school to join the U.S. Army. Afraid that he might die in World War I with his literary dreams unfulfilled, in the weeks before reporting for duty Fitzgerald hastily wrote a novel called The Romantic Egotist. Although the publisher Charles Scribner's Sons rejected the novel, the reviewer noted its originality and encouraged Fitzgerald to submit more work in the future.

Fitzgerald was commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry and assigned to Camp Sheridan outside of Montgomery, Alabama. While at a country club, Fitzgerald met and fell in love with Zelda Sayre (1900–1948), the daughter of an Alabama Supreme Court justice and the "golden girl", in Fitzgerald's terms, of Montgomery youth society. The war ended in 1918, before Fitzgerald was ever deployed, and upon his discharge he moved to New York City hoping to launch a career in advertising that would be lucrative enough to convince Zelda to marry him. He worked for the Barron Collier advertising agency, living in a single room at 200 Claremont Avenue in the Morningside Heights neighborhood on Manhattan's west side.

Zelda accepted his marriage proposal, but after some time and despite working at an advertising firm and writing short stories, he was unable to convince her that he would be able to support her, leading her to break off the engagement. Fitzgerald returned to his parents' house at 599 Summit Avenue, on Cathedral Hill, in St. Paul, to revise The Romantic Egoist, recast as This Side of Paradise, a semi-autobiographical account of Fitzgerald's undergraduate years at Princeton. Fitzgerald was so short of money that he took up a job repairing car roofs. His revised novel was accepted by Scribner's in the fall of 1919 and was published on March 26, 1920 and became an instant success, selling 41,075 copies in the first year it was published. It launched Fitzgerald's career as a writer and provided a steady income suitable to Zelda's needs. They resumed their engagement and were married in St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York. Their daughter and only child, Frances Scott "Scottie" Fitzgerald, was born on October 26, 1921.

Paris in the 1920s proved the most influential decade of Fitzgerald's development. Fitzgerald made several excursions to Europe, mostly Paris and the French Riviera, and became friends with many members of the American expatriate community in Paris, notably Ernest Hemingway. Fitzgerald's friendship with Hemingway was quite vigorous, as many of Fitzgerald's relationships would prove to be. Hemingway did not get on well with Zelda. In addition to describing her as "insane" he claimed that she "encouraged her husband to drink so as to distract Fitzgerald from his work on his novel", the other work being the short stories he sold to magazines. Like most professional authors at the time, Fitzgerald supplemented his income by writing short stories for such magazines as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's Weekly, and Esquire, and sold his stories and novels to Hollywood studios. This "whoring", as Fitzgerald and, subsequently, Hemingway called these sales, was a sore point in the authors' friendship. Fitzgerald claimed that he would first write his stories in an authentic manner but then put in "twists that made them into saleable magazine stories". Although Fitzgerald's passion lay in writing novels, only his first novel sold well enough to support the opulent lifestyle that he and Zelda adopted as New York celebrities. (The Great Gatsby, now considered to be his masterpiece, did not become popular until after Fitzgerald's death.) Because of this lifestyle, as well as the bills from Zelda's medical care when they came, Fitzgerald was constantly in financial trouble and often required loans from his literary agent, Harold Ober, and his editor at Scribner's, Maxwell Perkins. When Ober decided not to continue advancing money to Fitzgerald, the author severed ties with his longtime friend and agent. (Fitzgerald offered a good-hearted and apologetic tribute to this support in the late short story "Financing Finnegan".)

Fitzgerald began working on his fourth novel during the late 1920s but was sidetracked by financial difficulties that necessitated his writing commercial short stories, and by the schizophrenia that struck Zelda in 1930. Her emotional health remained fragile for the rest of her life. In February 1932, she was hospitalized at the Phipps Clinic at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Maryland. During this time, Fitzgerald rented the "La Paix" estate in the suburb of Towson, Maryland to work on his latest book, the story of the rise and fall of Dick Diver, a promising young psychiatrist who falls in love with and marries Nicole Warren, one of his patients. The book went through many versions, the first of which was to be a story of matricide. Some critics have seen the book as a thinly-veiled autobiographical novel recounting Fitzgerald's problems with his wife, the corrosive effects of wealth and a decadent lifestyle, his own egoism and self-confidence, and his continuing alcoholism. Indeed, Fitzgerald was extremely protective of his "material" (i.e., their life together). When Zelda wrote and sent to Scribner's her own fictional version of their lives in Europe, Save Me the Waltz, Fitzgerald was angry and was able to make some changes prior to the novel's publication, and convince her doctors to keep her from writing any more about what he called his "material", which included their relationship. His book was finally published in 1934 as Tender Is the Night. Critics who had waited nine years for the followup to The Great Gatsby had mixed opinions about the novel. Most were thrown off by its three-part structure and many felt that Fitzgerald had not lived up to their expectations. The novel did not sell well upon publication but, like the earlier Gatsby, the book's reputation has since risen significantly. Fitzgerald's alcoholism and financial difficulties, in addition to Zelda's mental illness, made for difficult years in Baltimore. He was hospitalized nine times at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and his friend H.L. Mencken noted in a 1934 letter that "The case of F. Scott Fitzgerald has become distressing. He is boozing in a wild manner and has become a nuisance."

In 1937, Fitzgerald moved to Hollywood, and he made his highest annual income thus far of $29,757.87. Most of the income came from short story sales. Besides writing, he also started to get involved in the film industry. Although he reportedly found movie work degrading, Fitzgerald was once again in dire financial straits, and spent the second half of the 1930s in Hollywood, working on commercial short stories, scripts for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (including some unfilmed work on Gone with the Wind), and his fifth and final novel, The Love of the Last Tycoon. Published posthumously as The Last Tycoon, it was based on the life of film executive Irving Thalberg. Among his other film projects was Madame Curie, for which he received no credit. In 1939, MGM ended the contract, and Fitzgerald became a freelance screenwriter. However, during all this, Fitzgerald's alcoholic tendencies still remained, and conflict with Zelda surfaced. Fitzgerald and Zelda became estranged; she continued living in mental institutions on the East Coast, while he lived with his lover Sheilah Graham, the gossip columnist, in Hollywood. In addition, records from the 1940 US Census reflect that he was officially living at the estate of Edward Everett Horton in Encino, California in the San Fernando Valley. From 1939 until his death in 1940, Fitzgerald mocked himself as a Hollywood hack through the character of Pat Hobby in a sequence of 17 short stories, later collected as "The Pat Hobby Stories", which garnered many positive reviews. The Pat Hobby Stories were published in The Esquire and appeared from January 1940 to July 1941, even after Fitzgerald died.

Fitzgerald had been an alcoholic since his college days, and became notorious during the 1920s for his extraordinarily heavy drinking, leaving him in poor health by the late 1930s. According to Zelda's biographer, Nancy Milford, Fitzgerald claimed that he had contracted tuberculosis, but Milford dismisses it as a pretext to cover his drinking problems. However, Fitzgerald scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli contends that Fitzgerald did in fact have recurring tuberculosis, and according to Nancy Milford, Fitzgerald biographer Arthur Mizener said that Fitzgerald suffered a mild attack of tuberculosis in 1919, and in 1929 he had "what proved to be a tubercular hemorrhage". It has been said that the hemorrhage was caused by bleeding from esophageal varices.

Fitzgerald suffered two heart attacks in the late 1930s. After the first, in Schwab's Drug Store, he was ordered by his doctor to avoid strenuous exertion. He moved in with Sheilah Graham, who lived in Hollywood on North Hayworth Avenue, one block east of Fitzgerald's apartment on North Laurel Avenue. Fitzgerald had two flights of stairs to climb to his apartment; Graham's was on the ground floor. On the night of December 20, 1940, Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham attended the premiere of This Thing Called Love starring Rosalind Russell and Melvyn Douglas. As the two were leaving the Pantages Theater, Fitzgerald experienced a dizzy spell and had trouble leaving the theater; upset, he said to Graham, "They think I am drunk, don't they?"

The following day, as Fitzgerald ate a candy bar and made notes in his newly arrived Princeton Alumni Weekly, Graham saw him jump from his armchair, grab the mantelpiece, gasp, and fall to the floor. She ran to the manager of the building, Harry Culver, founder of Culver City. Upon entering the apartment to assist Fitzgerald, he stated, "I'm afraid he's dead." Fitzgerald had died of a heart attack. His body was moved to the Pierce Brothers Mortuary.

Among the attendants at a visitation held at a funeral home was Dorothy Parker, who reportedly cried and murmured "the poor son-of-a-bitch", a line from Jay Gatsby's funeral in Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. His body was transported to Maryland, where his funeral was attended by twenty or thirty people in Bethesda; among the attendants were his only child, Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald Lanahan Smith (then age 19), and his editor, Maxwell Perkins. Fitzgerald was originally buried in Rockville Union Cemetery. Zelda died in 1948, in a fire at the Highland Mental Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. Scottie Smith worked to overturn the Archdiocese of Baltimore's ruling that Fitzgerald died a non-practicing Catholic, so that he could be buried at the Roman Catholic Saint Mary's Cemetery where his father's family was interred; this involved "re-Catholicizing" Fitzgerald after his death. Both of the Fitzgeralds' remains were moved to the family plot in Saint Mary's Cemetery, in Rockville, Maryland, in 1975.

Fitzgerald died before he could complete The Love of the Last Tycoon. His manuscript, which included extensive notes for the unwritten part of the novel's story, was edited by his friend, the literary critic Edmund Wilson, and published in 1941 as The Last Tycoon. In 1994 the book was reissued under the original title The Love of the Last Tycoon, which is now agreed to have been Fitzgerald's preferred title.

(source wikiperdia.org)

F. Scott Fitzgerald

THIS SIDE OF PARADISE

Arcadia Ebooks 2016

www.arcadiaebooks.altervista.org

F. Scott Fitzgerald

This Side of Paradise

(1920)

THIS SIDE OF PARADISE

... Well this side of Paradise!... There's little comfort in the wise.Rupert Brooke.

Experience is the name so many people give to their mistakes.

To Sigourney Fay

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER 1 Amory, Son of Beatrice

Amory Blaine inherited from his mother every trait, except the stray inexpressible few, that made him worth while. His father, an ineffectual, inarticulate man with a taste for Byron and a habit of drowsing over the Encyclopedia Britannica, grew wealthy at thirty through the death of two elder brothers, successful Chicago brokers, and in the first flush of feeling that the world was his, went to Bar Harbor and met Beatrice O'Hara. In consequence, Stephen Blaine handed down to posterity his height of just under six feet and his tendency to waver at crucial moments, these two abstractions appearing in his son Amory. For many years he hovered in the background of his family's life, an unassertive figure with a face half-obliterated by lifeless, silky hair, continually occupied in "taking care" of his wife, continually harassed by the idea that he didn't and couldn't understand her.

But Beatrice Blaine! There was a woman! Early pictures taken on her father's estate at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, or in Rome at the Sacred Heart Convent—an educational extravagance that in her youth was only for the daughters of the exceptionally wealthy—showed the exquisite delicacy of her features, the consummate art and simplicity of her clothes. A brilliant education she had—her youth passed in renaissance glory, she was versed in the latest gossip of the Older Roman Families; known by name as a fabulously wealthy American girl to Cardinal Vitori and Queen Margherita and more subtle celebrities that one must have had some culture even to have heard of. She learned in England to prefer whiskey and soda to wine, and her small talk was broadened in two senses during a winter in Vienna. All in all Beatrice O'Hara absorbed the sort of education that will be quite impossible ever again; a tutelage measured by the number of things and people one could be contemptuous of and charming about; a culture rich in all arts and traditions, barren of all ideas, in the last of those days when the great gardener clipped the inferior roses to produce one perfect bud.

In her less important moments she returned to America, met Stephen Blaine and married him—this almost entirely because she was a little bit weary, a little bit sad. Her only child was carried through a tiresome season and brought into the world on a spring day in ninety-six.

When Amory was five he was already a delightful companion for her. He was an auburn-haired boy, with great, handsome eyes which he would grow up to in time, a facile imaginative mind and a taste for fancy dress. From his fourth to his tenth year he did the country with his mother in her father's private car, from Coronado, where his mother became so bored that she had a nervous breakdown in a fashionable hotel, down to Mexico City, where she took a mild, almost epidemic consumption. This trouble pleased her, and later she made use of it as an intrinsic part of her atmosphere—especially after several astounding bracers.

So, while more or less fortunate little rich boys were defying governesses on the beach at Newport, or being spanked or tutored or read to from "Do and Dare," or "Frank on the Mississippi," Amory was biting acquiescent bell-boys in the Waldorf, outgrowing a natural repugnance to chamber music and symphonies, and deriving a highly specialized education from his mother.

"Amory."

"Yes, Beatrice." (Such a quaint name for his mother; she encouraged it.)

"Dear, don't think of getting out of bed yet. I've always suspected that early rising in early life makes one nervous. Clothilde is having your breakfast brought up."

"All right."

"I am feeling very old to-day, Amory," she would sigh, her face a rare cameo of pathos, her voice exquisitely modulated, her hands as facile as Bernhardt's. "My nerves are on edge—on edge. We must leave this terrifying place to-morrow and go searching for sunshine."

Amory's penetrating green eyes would look out through tangled hair at his mother. Even at this age he had no illusions about her.

"Amory."

"Oh, yes."

"I want you to take a red-hot bath as hot as you can bear it, and just relax your nerves. You can read in the tub if you wish."

She fed him sections of the "Fetes Galantes" before he was ten; at eleven he could talk glibly, if rather reminiscently, of Brahms and Mozart and Beethoven. One afternoon, when left alone in the hotel at Hot Springs, he sampled his mother's apricot cordial, and as the taste pleased him, he became quite tipsy. This was fun for a while, but he essayed a cigarette in his exaltation, and succumbed to a vulgar, plebeian reaction. Though this incident horrified Beatrice, it also secretly amused her and became part of what in a later generation would have been termed her "line."

"This son of mine," he heard her tell a room full of awestruck, admiring women one day, "is entirely sophisticated and quite charming—but delicate—we're all delicate; here, you know." Her hand was radiantly outlined against her beautiful bosom; then sinking her voice to a whisper, she told them of the apricot cordial. They rejoiced, for she was a brave raconteuse, but many were the keys turned in sideboard locks that night against the possible defection of little Bobby or Barbara...

These domestic pilgrimages were invariably in state; two maids, the private car, or Mr. Blaine when available, and very often a physician. When Amory had the whooping-cough four disgusted specialists glared at each other hunched around his bed; when he took scarlet fever the number of attendants, including physicians and nurses, totalled fourteen. However, blood being thicker than broth, he was pulled through.

The Blaines were attached to no city. They were the Blaines of Lake Geneva; they had quite enough relatives to serve in place of friends, and an enviable standing from Pasadena to Cape Cod. But Beatrice grew more and more prone to like only new acquaintances, as there were certain stories, such as the history of her constitution and its many amendments, memories of her years abroad, that it was necessary for her to repeat at regular intervals. Like Freudian dreams, they must be thrown off, else they would sweep in and lay siege to her nerves. But Beatrice was critical about American women, especially the floating population of ex-Westerners.

"They have accents, my dear," she told Amory, "not Southern accents or Boston accents, not an accent attached to any locality, just an accent"—she became dreamy. "They pick up old, moth-eaten London accents that are down on their luck and have to be used by some one. They talk as an English butler might after several years in a Chicago grand-opera company." She became almost incoherent—"Suppose—time in every Western woman's life—she feels her husband is prosperous enough for her to have—accent—they try to impress me, my dear—"

Though she thought of her body as a mass of frailties, she considered her soul quite as ill, and therefore important in her life. She had once been a Catholic, but discovering that priests were infinitely more attentive when she was in process of losing or regaining faith in Mother Church, she maintained an enchantingly wavering attitude. Often she deplored the bourgeois quality of the American Catholic clergy, and was quite sure that had she lived in the shadow of the great Continental cathedrals her soul would still be a thin flame on the mighty altar of Rome. Still, next to doctors, priests were her favorite sport.

"Ah, Bishop Wiston," she would declare, "I do not want to talk of myself. I can imagine the stream of hysterical women fluttering at your doors, beseeching you to be simpatico"—then after an interlude filled by the clergyman—"but my mood—is—oddly dissimilar."

Only to bishops and above did she divulge her clerical romance. When she had first returned to her country there had been a pagan, Swinburnian young man in Asheville, for whose passionate kisses and unsentimental conversations she had taken a decided penchant—they had discussed the matter pro and con with an intellectual romancing quite devoid of sappiness. Eventually she had decided to marry for background, and the young pagan from Asheville had gone through a spiritual crisis, joined the Catholic Church, and was now—Monsignor Darcy.

"Indeed, Mrs. Blaine, he is still delightful company—quite the cardinal's right-hand man."

"Amory will go to him one day, I know," breathed the beautiful lady, "and Monsignor Darcy will understand him as he understood me."

Amory became thirteen, rather tall and slender, and more than ever on to his Celtic mother. He had tutored occasionally—the idea being that he was to "keep up," at each place "taking up the work where he left off," yet as no tutor ever found the place he left off, his mind was still in very good shape. What a few more years of this life would have made of him is problematical. However, four hours out from land, Italy bound, with Beatrice, his appendix burst, probably from too many meals in bed, and after a series of frantic telegrams to Europe and America, to the amazement of the passengers the great ship slowly wheeled around and returned to New York to deposit Amory at the pier. You will admit that if it was not life it was magnificent.

After the operation Beatrice had a nervous breakdown that bore a suspicious resemblance to delirium tremens, and Amory was left in Minneapolis, destined to spend the ensuing two years with his aunt and uncle. There the crude, vulgar air of Western civilization first catches him—in his underwear, so to speak.

His lip curled when he read it.

"I am going to have a bobbing party," it said, "on Thursday, December the seventeenth, at five o'clock, and I would like it very much if you could come.

Yours truly

R.S.V.P.

Myra St. Claire.

He had been two months in Minneapolis, and his chief struggle had been the concealing from "the other guys at school" how particularly superior he felt himself to be, yet this conviction was built upon shifting sands. He had shown off one day in French class (he was in senior French class) to the utter confusion of Mr. Reardon, whose accent Amory damned contemptuously, and to the delight of the class. Mr. Reardon, who had spent several weeks in Paris ten years before, took his revenge on the verbs, whenever he had his book open. But another time Amory showed off in history class, with quite disastrous results, for the boys there were his own age, and they shrilled innuendoes at each other all the following week:

"Aw—I b'lieve, doncherknow, the Umuricun revolution was lawgely an affair of the middul clawses," or "Washington came of very good blood—aw, quite good—I b'lieve."

Amory ingeniously tried to retrieve himself by blundering on purpose. Two years before he had commenced a history of the United States which, though it only got as far as the Colonial Wars, had been pronounced by his mother completely enchanting.

His chief disadvantage lay in athletics, but as soon as he discovered that it was the touchstone of power and popularity at school, he began to make furious, persistent efforts to excel in the winter sports, and with his ankles aching and bending in spite of his efforts, he skated valiantly around the Lorelie rink every afternoon, wondering how soon he would be able to carry a hockey-stick without getting it inexplicably tangled in his skates.

The invitation to Miss Myra St. Claire's bobbing party spent the morning in his coat pocket, where it had an intense physical affair with a dusty piece of peanut brittle. During the afternoon he brought it to light with a sigh, and after some consideration and a preliminary draft in the back of Collar and Daniel's "First-Year Latin," composed an answer:

My dear Miss St. Claire:

Your truly charming envitation for the evening of next Thursday evening was truly delightful to receive this morning. I will be charm and inchanted indeed to present my compliments on next Thursday evening.

Faithfully,

Amory Blaine.

On Thursday, therefore, he walked pensively along the slippery, shovel-scraped sidewalks, and came in sight of Myra's house, on the half-hour after five, a lateness which he fancied his mother would have favored. He waited on the door-step with his eyes nonchalantly half-closed, and planned his entrance with precision. He would cross the floor, not too hastily, to Mrs. St. Claire, and say with exactly the correct modulation:

"My dear Mrs. St. Claire, I'm frightfully sorry to be late, but my maid"—he paused there and realized he would be quoting—"but my uncle and I had to see a fella—Yes, I've met your enchanting daughter at dancing-school."

Then he would shake hands, using that slight, half-foreign bow, with all the starchy little females, and nod to the fellas who would be standing 'round, paralyzed into rigid groups for mutual protection.

A butler (one of the three in Minneapolis) swung open the door. Amory stepped inside and divested himself of cap and coat. He was mildly surprised not to hear the shrill squawk of conversation from the next room, and he decided it must be quite formal. He approved of that—as he approved of the butler.

"Miss Myra," he said.

To his surprise the butler grinned horribly.

"Oh, yeah," he declared, "she's here." He was unaware that his failure to be cockney was ruining his standing. Amory considered him coldly.

"But," continued the butler, his voice rising unnecessarily, "she's the only one what is here. The party's gone."

Amory gasped in sudden horror.

"What?"

"She's been waitin' for Amory Blaine. That's you, ain't it? Her mother says that if you showed up by five-thirty you two was to go after 'em in the Packard."

Amory's despair was crystallized by the appearance of Myra herself, bundled to the ears in a polo coat, her face plainly sulky, her voice pleasant only with difficulty.

"'Lo, Amory."

"'Lo, Myra." He had described the state of his vitality.

"Well—you got here, anyways."

"Well—I'll tell you. I guess you don't know about the auto accident," he romanced.

Myra's eyes opened wide.

"Who was it to?"

"Well," he continued desperately, "uncle 'n aunt 'n I."

"Was any one killed?"

Amory paused and then nodded.

"Your uncle?"—alarm.

"Oh, no just a horse—a sorta gray horse."

At this point the Erse butler snickered.

"Probably killed the engine," he suggested. Amory would have put him on the rack without a scruple.

"We'll go now," said Myra coolly. "You see, Amory, the bobs were ordered for five and everybody was here, so we couldn't wait—"

"Well, I couldn't help it, could I?"

"So mama said for me to wait till ha'past five. We'll catch the bobs before it gets to the Minnehaha Club, Amory."

Amory's shredded poise dropped from him. He pictured the happy party jingling along snowy streets, the appearance of the limousine, the horrible public descent of him and Myra before sixty reproachful eyes, his apology—a real one this time. He sighed aloud.

"What?" inquired Myra.

"Nothing. I was just yawning. Are we going to surely catch up with 'em before they get there?" He was encouraging a faint hope that they might slip into the Minnehaha Club and meet the others there, be found in blasé seclusion before the fire and quite regain his lost attitude.

"Oh, sure Mike, we'll catch 'em all right—let's hurry."

He became conscious of his stomach. As they stepped into the machine he hurriedly slapped the paint of diplomacy over a rather box-like plan he had conceived. It was based upon some "trade-lasts" gleaned at dancing-school, to the effect that he was "awful good-looking and English, sort of."

"Myra," he said, lowering his voice and choosing his words carefully, "I beg a thousand pardons. Can you ever forgive me?" She regarded him gravely, his intent green eyes, his mouth, that to her thirteen-year-old, arrow-collar taste was the quintessence of romance. Yes, Myra could forgive him very easily.

"Why—yes—sure."

He looked at her again, and then dropped his eyes. He had lashes.

"I'm awful," he said sadly. "I'm diff'runt. I don't know why I make faux pas. 'Cause I don't care, I s'pose." Then, recklessly: "I been smoking too much. I've got t'bacca heart."

Myra pictured an all-night tobacco debauch, with Amory pale and reeling from the effect of nicotined lungs. She gave a little gasp.

"Oh, Amory, don't smoke. You'll stunt your growth!"

"I don't care," he persisted gloomily. "I gotta. I got the habit. I've done a lot of things that if my fambly knew"—he hesitated, giving her imagination time to picture dark horrors—"I went to the burlesque show last week."

Myra was quite overcome. He turned the green eyes on her again. "You're the only girl in town I like much," he exclaimed in a rush of sentiment. "You're simpatico."

Myra was not sure that she was, but it sounded stylish though vaguely improper.

Thick dusk had descended outside, and as the limousine made a sudden turn she was jolted against him; their hands touched.

"You shouldn't smoke, Amory," she whispered. "Don't you know that?"

He shook his head.

"Nobody cares."

Myra hesitated.

"I care."

Something stirred within Amory.

"Oh, yes, you do! You got a crush on Froggy Parker. I guess everybody knows that."

"No, I haven't," very slowly.

A silence, while Amory thrilled. There was something fascinating about Myra, shut away here cosily from the dim, chill air. Myra, a little bundle of clothes, with strands of yellow hair curling out from under her skating cap.

"Because I've got a crush, too—" He paused, for he heard in the distance the sound of young laughter, and, peering through the frosted glass along the lamp-lit street, he made out the dark outline of the bobbing party. He must act quickly. He reached over with a violent, jerky effort, and clutched Myra's hand—her thumb, to be exact.

"Tell him to go to the Minnehaha straight," he whispered. "I wanta talk to you—I got to talk to you."