Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

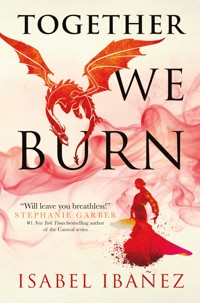

Enter the scorching arena of dragons and dance in this Spanish-inspired swoonworthy fantasy where Fireborne meets A Natural History of Dragons. Fans of Marie Brennan and Naomi Novik will love this richly imagined world full of excitement. An ancient city plagued by dragons. Eighteen-year-old Zarela Zalvidar is a talented flamenco dancer and daughter of the most famous Dragonador in Hispalia. People come from miles to see him fight in their arena, which will one day be hers. But disaster strikes during one celebratory show, and in the carnage, Zarela's life changes in an instant. A flamenco dancer determined to save her ancestral home. Facing punishment from the Dragon Guild, Zarela must keep the arena—her ancestral home and inheritance—safe from their greedy hands. She has no choice but to train to become a Dragonador. When the infuriatingly handsome dragon hunter, Arturo Díaz de Montserrat, withholds his help, she refuses to take no for an answer. Without him, her world will burn. But even if he agrees, there's someone out to ruin the Zalvidar family, and Zarela will have to do whatever it takes in order to prevent the Dragon Guild from taking away her birthright.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 557

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Gremios de hispalia

Dragones de hispalia

Prologue

Uno

Dos

Tres

Cuatro

Cinco

Seis

Siete

Ocho

Nueve

Diez

Once

Doce

Trece

Catorce

Quince

Dieciséis

Diecisiete

Dieciocho

Diecinueve

Veinte

Veintiuno

Veintidós

Veintitrés

Veinticuatro

Veinticinco

Veintiséis

Veintisiete

Veintiocho

Veintinueve

Treinta

Treinta Y Uno

Treinta Y Dos

Treinta Y Tres

Treinta Y Cuatro

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Together We BurnPrint edition ISBN: 9781803360362E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360379

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: July 202210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© 2022 Isabel Ibañez. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Mamita and Abuelita Consuelo,you both are the passionate and stubbornYA heroines I’ve always looked up to.

In Loving Memory ofTeresa Díaz de Beccar

GREMIOS DE HISPALIA

GUILDS OF HISPALIA

GREMIO DE DRAGONADORES

Dragonadores, Dragon Hunters and Tamers,Arena Owners, Dragonador Instructors

GREMIO DE MAGIA

Magos and Brujas

GREMIO DE SANADORES

Healers, Botanists, Apothecary Owners

GREMIO DE COMERCIANTES

Merchants, Lenders, Traders, Carpenters, Blacksmiths

GREMIO DE LOS SASTRES

Textile Workers, Seamstresses, Launderesses, Tailors

GREMIO DE ANIMALES Y VEGETALES COMERCIALES

Butchers, Hunters, Farmers

GREMIO DE LAS ARTES

Painters, Sculptors, Dancers, Actors and Actresses, Singers, Writers, Weavers

GREMIO DE NOTICIAS

Writers, Printers, Publications

GREMIO DEL MAR

Fishermen, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Navigators

GREMIO DE EJÉRCITO

Patrol, Guards, Army

GREMIO GENERAL

Open to the General Public

DRAGONES DE HISPALIA

DRAGONS OF HISPALIA

CULEBRA

Four legs, resembles a serpent. Small wings, flies short distance.Stays close to the ground, emerald scales. Shoots poisonous liquid.

LAGARTO

Swimmer dragon. Drowns victims before devouring.Shimmery, iridescent scales sold as jewelry.Found along the coast of Valentia.

RANCIO

Golden scales, red irises. Emits a gas that can rot whatever it touches.

MORCEGO

Black dragon with ivory horns. Breathes short bursts of fire.Great bat wings. Body shape resembles a bull.Preferred dragon for arenas.

RATÓN

The rat of the skies. White scales and gleaming red eyes.More common than rodents.Squat in length, round in the belly. Easy to overtake and kill.

ESCARLATA

The elusive and legendary red dragon. Believed to be near extinctand difficult to domineer.Ruby red scales, immense wings.Breathes fire for up to half a minute.

My mother died screaming my name.

Papá and I had traveled with her to La Bota, a theater outside Santivilla’s ancient round walls. I remember it was near an orange grove that tartly scented the air like a thick lemon wedge flavoring tea. Her performance was in celebration of the recent capture of the Escarlata, the legendary and elusive breed of dragon with scales the color of chili peppers. It was known for its fury and volatile nature, for the fire hidden deep in its belly. Only one or two are successfully brought down alive each year. We were all excited to see one, bound in iron.

We sat in the front row surrounding the circular stage, built a hundred years ago and where many flamenco dancers came to perform. It was Mamá’s favorite place to dance, out in the open, surrounded by the tangerine-hued mountains to the east and the ocean to the west.

Flamenco was born in Santivilla, the capital of Hispalia, and there’s nothing quite like it anywhere else. The blend of the guitarist’s strumming, my mother’s castañuelas, and the citrus-scented air makes what we in Hispalia call the perfect ambiente.

We all should have been safe. The red dragon was in chains and ready to face the Dragonador.

Papá handed me a plate piled high with toasted almonds, perfectly salted anchovies, and soft cheese, and I munched happily as we waited for Mamá to perform as the opening act for the fight. Off to the side, the bald guitarist was already settled on a sturdy wooden chair. Surrounding us was a tremendous crowd sitting on the stone benches, and together we were all drinking and merry to be under a cloudless blue sky, even if the heat was remorseless, making my embroidered dress stick to my sweat-soaked skin.

It was the beginning of spring, just days after we celebrated the death of winter. It was too hot for my mantilla, and instead, I left my arms and shoulders unprotected under the metallic sun, hanging straight over our heads.

“I forget, Zarela,” Papá had whispered in my ear. I squirmed away from his thick beard, still black and without a touch of silver. “Do you know this dance?”

I nodded. “Mamá taught me last month.”

When Papá smiled, he did so with his whole face. His dark eyes crinkled, the dimples on both cheeks deepened, and the scruff of his beard moved with his mouth as it reached for his ears.

The guitarist started strumming his instrument, and he was truly excellent, because within moments he made the guitar sing and cry and roar, and the music rode the wind until my body thrummed with each note. Then there was a sudden silence. The crowd surged to their feet, stomping and whistling as Mamá climbed onto the stone stage.

My breath caught at the back of my throat.

She stood in the center, arms curled high above her head, and the fabric of her tight, flaming red dress hugged the curve of her back and fluttered in long ripples around her legs. Still, my mother wouldn’t move until she found the beat, counting in her head.

Her hip dropped and she twirled her wrists. The notes propelled my mother in circles, her strong legs stomping on the stage, fingers twisting high in the air. Her dark, curly hair whipped around her face—she refused to braid it at the crown of her head like most flamenco dancers, because according to her, what’s the point of whirling in tight circles if you can’t feel the wind in your hair. The expression of joy on her face was clearly visible, mesmerizing.

I hated taking my gaze off Mamá when she was preforming, even for a moment, but I did it anyway because there’s only one thing better than watching her on stage: the look on Papá’s face. He was bending forward, elbows on his knees, slack-jawed, and dark eyes intently focused on Mamá. He knew every step of this routine, every turn her head made. She danced the way she loved: steadfast, gracious, wildly, and slightly aggressive.

The musician ended the song with a flourish, and Mamá’s performance finished with her back arched and her left foot giving one last, loud stomp. I jumped to my feet, clapping and roaring along with Papá and the hundreds of spectators who threw gardenias onto the stage. Mamá grinned and found us, her arms stretched wide as if reaching for the ends of the earth. Her glittering, dark gaze landed on mine and she whispered, “te quiero.” I mouthed it back to her, and Papá dragged a heavy arm across my shoulders, pulling me to his side. He smelled like chicory and tobacco and the orange he’d devoured earlier.

We beamed at her, and she bowed, facing her familia.

She swept off the stage. Papá remained to save our seats, and he merrily waved as I left him to join Mamá in the changing rooms next to the stage. She gave me a hug and kiss on the temple, asked me to fix her hair while the Dragonador entered the arena. I remember the sound of applause as the Escarlata was let loose, and the fighter began his dance with fate. I hurried to pin Mamá’s hair back, eager to rush back to our seats in order to see the death of the red dragon. Even Papá had only killed the breed just once in our arena. It was sure to be quite a match, and I didn’t want to miss it.

Mamá turned to me and tucked a gardenia in my hair.

That was my last moment with her.

Bloodcurdling screams bellowed from the arena. Mamá immediately shoved me inside one of the curtained-off areas where performers could freshen up before their event and asked me to stay hidden, told me that she was going to find Papá.

Then she was gone.

I didn’t want to stay behind and hide. The yelling grew louder, the sound of fire blasting from the monster became incessant. I rushed out of the dressing room and raced to the ring, my sandals smacking against the hot stone. I remember my breath freezing in my chest at the sight of the Escarlata racing around the arena, its wings having somehow escaped their iron binding.

The monster was free.

It wasted no time in launching itself from the hard, packed sand of the arena. The red dragon flew around stage, its bloodred scales glinting horribly in the sunlight, and a terrible, frightening stream of fire erupted from its mouth in one long gust. It scorched parts of the crowd, the stage, the poor guitarist still clutching his instrument. Mamá was not even ten feet from where he stood. My gaze met hers.

“Go back!” she yelled. “Zarela!”

The tunnel of flames swerved and she was engulfed, and a guttural scream ripped out of her as her body burned. The heat from the blast was thick, and I choked on the smoke and scent of singed hair and flesh. The crowd ran in every direction, someone slammed into me and knocked me off my feet. The gravel stung my cheeks, and my hand bled from the shards of someone’s plate. I pulled a jagged piece from out of my palm, hissing loudly.

The Escarlata opened its jaws wide, readying to let out another fiery blast.

Papá found me on the ground and pulled me to my feet, and then yanked me away from the dragon ring, from the sight of my burning mamá. We ran for the orange grove, kicking dust in our wake, and hid under the thick leaves. I gripped Papá, sobbing against his chest, and the sound of his heart hammered against my cheek. He pulled me deeper within the tree’s canopy. The branches scratched my bare arms. The blossoms smelled like rotting fruit.

I never ate another orange again.

Underneath my feet, the dragon waits.

Almost unconsciously, my attention drifts to the cobbled ground. I picture the dungeon below this tunnel, the horrid damp smell, the shadows crowding the corners and swift turns, and the row of cages where the monsters are kept under lock and key. In my mind, the beast moves restlessly in its cell, waiting for the moment the iron bars lift so it can bolt into the arena, searching for flesh, for a glimpse of the color red. The image incites a riot in my blood.

The trapped air inside the tunnel glides down my throat, fills my belly. When I exhale, some of the fear goes with it. My mind clears as I quicken my steps, following the curved wall made of craggy stone.

I have minutes before my flamenco routine.

La Giralda’s iron bell triumphantly heralds the start of our five hundredth anniversary show, and the sound carries to every corner of Santivilla and sinks into my skin, rattling bone. It’s a siren’s calling, promising the best entertainment you’ll see all week, for the not-so-bargain price of twenty-seven reales. Outside the arena, there’s a long line curling around the building of those keen on still entering.

But there’s not an empty seat left in our dragon ring.

We’re the best at what we do, a set of familial skills passed down for centuries. Papá is descended from a long line of Dragonadores, famous for their courage in the ring. This building made of stone and brick and sweat is in my blood. The most prized possession belonging to the Zalvidar name, and one day it will be mine.

I walk along the underbelly of the ring, my wooden heels slapping against the stone corridor that leads to the arena, famous for its white sand that glitters under the sun. It’s brought in from the coast, carted on dozens of wagons pulled by several pairs of oxen, an effort well worth its price. There’s nothing quite like the look of spilled blood against something so pure.

My tomato-red flamenco dress swishes around my ankles, and I run my fingers along the craggy walls. I approach the entrance, and the roar of the crowd booms loud and insatiable. The sound skips down my spine, and a pleasant shiver dances across my skin. I almost forget about the dragon waiting to be unleashed.

Almost, but not quite.

Lola Delgado gently nudges me. “Are you worried about the dragon, the dance, or both?” She tugs impatiently at her wild dark hair. Lola gives up stuffing loose tendrils into her bun with a sigh. The light from the torches casts flickering shadows across her deeply tanned skin. She narrows her hazel eyes at me, understanding the reason behind the tight set to my mouth and why my knuckles turn white around my mother’s painted fan.

“It was one of my mother’s newest routines. An instant classic.”

Lola’s a head shorter than me, but even so, she manages to curl a protective arm around my shoulders. “The crowd will love you. They always do.” She drops her voice to a whisper. “Even if you perform one of your dance routines.”

She’s willfully forgetting about the last time I tried to do one of my own creations. The crowd was expecting to see a traditional routine of my mother’s, but I gave them one of mine. It still unsettles me—how quickly their cheers turned into disappointed shouting and insults.

I had finished the moves with my chin held high, even though I wanted to lie down on the hot sand and cover my ears so I couldn’t hear their yelling. I’ve never forgotten how little the people of Santivilla think of me.

But what truly destroyed me that day was the bitter gleam of sadness in Papá’s eyes, his thin smile that told me that even he wasn’t interested in seeing anything but my mother’s routines.

“They want Eulalia Zalvidar.” People want her brilliance on the dance floor, the luring sway of her hips, the way she could make you feel bold and inspired, all from watching her stamp across the stage. This is why I dance steps that belonged to her first.

She frowns. “Zarela . . .”

“It’s fine.” I straighten away from her, ears straining to hear the music that’ll signal my entrance. “Estoy bien, no te preocupes.”

“I do worry about you,” she says. “And it’s not fair. You’re the responsible one.”

“Just tell me I look presentable.” I lift up the skirt, letting the ruffles skim my ankles. “How does the dress look?”

She reaches forward and rearranges the collar so the pleats lay flat. As one of the maids of the household, she’s responsible for making sure I look the part. “Estás guapísima.”

“Thanks to you,” I say with a small smile.

She grins and her round cheeks flush prettily. Anytime we talk about clothing, her eyes light up. Had her circumstances been different, she could have apprenticed at the Gremio de los Sastres, the guild of tailors and textile workers, but her family couldn’t afford to send her. Now she works alongside our housekeeper, Ofelia, helping with the cooking and cleaning. But over the years, I’ve hired her to design and sew new dresses for my flamenco routines.

Her talent ought not to be wasted on dirty linens.

“Oh, I know I did a fabulous job with the alterations.”

“Your humility moves me.”

She continues as if I haven’t spoken. “And that dress is doing marvelous things for your—”

I narrow my gaze. “Let me stop you right there.”

“What? I was only trying to say that the fabric drapes in all the right—”

“Lola.”

She winks at me, and I resist hitting her with my mother’s fan. She’s trying to distract me, but my nerves roar to life despite her outrageous flattery. The crowd’s cheering is insistent, demanding to be entertained like a child. The sound envelopes us in a fiery rush. Lola winces. I lean forward, unable to keep the smirk off my face. “Did we drink a little too much manzanilla last night? The sherry always gives you a headache.”

“Ugh,” she mumbles. “I resent your horrid, smug tone. To think I came down here to make sure you were fine—” She breaks off, swaying on her feet.

“You came down here to see Guillermo,” I cut in with an arched brow. “Admit it.”

She looks away, biting her lip.

“What happened to Rosita?”

Lola rolls her eyes. “She was too wild.”

“But you’re wild,” I say laughingly.

“Exactly. I can barely take care of myself. I’m too young to worry about anyone else.”

I gently push her behind me, as I desperately fight a laugh. “You’re a menace. Go find a seat.”

“If you see him,” she says with a sly smile. “Tell him I like the way his pants fit.”

“I will never say such nonsense to him or anyone, ever.”

“What?” she asks innocently. “He’s entirely too handsome for someone so studious. Someone ought to let him know.”

Personally, I don’t understand Guillermo’s appeal. As a member of the Gremio de Magia, he spends most of his day bent over chopped-up dragon parts: pulled-out teeth, sawed-off ivory horns, and eyeballs stored in vats of oil. Guillermo is here now, somewhere in the arena, waiting for Papá to kill today’s monster so that he can pay for the remains and take them back to the Gremio in order to concoct more potions.

“I’ll tell him you say hello,” I say finally.

“That doesn’t sound like me in the slightest.”

“I’m not going to do your flirting for you. Not even if you ask nicely.”

Lola pouts and then stumbles away, and I let out a little laugh. I turn back around. I have to concentrate on my performance and not think of anything other than the steps and the music. I focus on my breath as it catches in my throat, and on my body coiled tight and ready for the show.

The entrance is an arched doorway, lined with cobblestone in varying hues of clay and the tawny sand outside the walled city of Santivilla. On the other side, patrons wave their sombreros in the air as they catch a glimpse of me, dressed as my unforgettable mother, wearing her flamenco dress and shoes. The outfit is endlessly bold, with ruffles adorning the off-shoulder neckline and hem. Lola altered the costume to fit my smaller frame perfectly.

But while I may style my black hair like she did, wear the same color rouge on my lips, and line my eyes in charcoal the way she liked, I am not my mother. I am the forgettable village next to her metropolis.

What she did was miraculous. I merely worship at the same altar.

Nerves grip my heart and squeeze. It’s always this way before I take the stage. I’m holding up my father’s name and my mother’s legacy. I inhale deeply, allowing the crowd’s cheering and sharp whistling and the sounds of the strumming guitar coming from the center of the ring to remind me of who I am: Zarela Zalvidar, daughter of the best performers in all of Hispalia.

I damn well better act like it.

This is the most important show we’ll ever put on, our five hundredth anniversary spectacle, covered by the national paper, Los Tiempos, and watched by wealthy patrons and prominent guild members from all over Hispalia. They’ve come with their velvet drawstring purses, lofty connections, and dreams of being entertained extravagantly in a city as beautiful as it is dangerous.

The crowd hushes at the sight of the guitarist settling onto his stool above the platform. Pressure builds in my chest. My shoulders are tight, and I roll each side. I inhale again, holding air captive deep in my lungs. I exhale, and I imagine my fear riding my breath, leaving me behind. I throw my shoulders back, my spine straight and proud like La Giralda’s bell tower, and I march toward the raised wooden platform in the middle of the arena, arms outstretched to meet the hundreds of spectators sitting around the ring. I keep my chin lifted high, and my grin wide enough for everyone to see. Five hundred spectators stomp their feet to the rhythm of the guitar, clapping their hands at a fast clip.

Ra-ta-ta-ta-ta-tat.

It’s a drug, that dizzying rush as people scream louder, wanting a part of me. Papá stands at the other designated entrance for performers, with a gleaming smile. He’s with his childhood friend, Tío Hector, a fellow Dragonador who owns a popular dragon ring across town. He’s not really my uncle, but I’ve always called him one for as long as I can remember.

The throng hushes. I close my eyes and wait for the beat. When I find it, I slowly stomp on the stage. The soles of my black leather shoes smack against the wood like a battering ram. The sound is the base of my performance, and the noise anchors me to my mother.

I sway my hips as the guitarist strums faster and faster, fingers moving quickly up and down the instrument. I spin and twirl, bending backward as I whip out my fan, flinging it open with a snap. The cheering starts anew, and I smile as I stomp and clap along to the rhythm of the music. I lay my fears to rest. In this moment, I relish the dance and the way the music glides along my body as I position my legs and torso into strong lines.

Grief has made me a better dancer. I command the stage and offer this tribute to Mamà, to her adoring fans who scream her name even now. It’s why I’ve stopped Papá from introducing me ahead of my performance.

The song ends at a slow crawl, and I move with the dying notes, bending forward in a traditional Hispalian bow. Sweat slides down the back of my neck, and my breath comes out in great huffs. Every dance is a fight against the ground, and my legs shake from the effort to win. Flowers rain, dropping dead at my feet. I straighten, wave at the patrons and their fat purses, and sashay to Papá and Hector where they wait by the second tunnel entrance, quietly proud. Papá carries an enormous bouquet of gardenias, the stems tied tightly with a gold ribbon, fluttering in the breeze like a banner beckoning me home. I take the flowers as Hector leans forward to fix the adornment in my hair, smiling broadly.

Papá curls a strong arm around my waist. “Preciosa. Just like your querida mamá.”

He studies my face, searching for my mother in the curve of my cheek and the fire in my eyes. But I’m not her. I can’t say the words out loud—he’d be crushed, so instead, I say what he needs. “Para Mamá. So we never forget her.”

A small smile tiptoes across his face, but I’m not fooled. He might convince a stranger that he’s happy, but I’ve seen what a real smile looks like, and that’s not it, though I’ve grown accustomed to this version.

Hector guides me backward, farther into the tunnel where the white sand no longer covers the ground. He yanks on a pocket iron bar door, dragging it forward until it slides into the gap on the opposite wall. Papá remains on the other side, closest to the arena. I reach between the slots, wanting Papá’s hand. I try to remain calm, remind myself that my father is the best Dragonador in all of Hispalia.

But the risk never fades.

Any fight could be his last.

Last week, a dragon wearing ribbons and a necklace made of flowers gored a fighter in the stomach in one of our rival’s arena. The man had died in front of hundreds, including his wife and two small children.

Papá strides to the center of the arena where the stage has already been removed, and all that’s left is the hot sand. His snug jacket encloses his strong arms, and his patent leather shoes are polished to a resplendent sheen. The ensemble he wears is startling white, stitched with red thread and adorned by a thousand beads in a burst of chaotic color, handmade and designed by Lola. It had taken her months of painstakingly sewing each sparkling piece onto the Dragonador costume, known everywhere in Hispalia as the traje de luces—suit of lights.

His broad shoulders are proud and straight enough to measure with, and his hands grip the golden handle of the red banner that bears our family name. Every step Papá takes adds flair and drama to the fight. He is a consummate entertainer and charmer. Born to please and impress. Passionate, quick to anger, and fiercely loyal.

In the arena, he is the most like the Papá I remember.

The lone iron gate rises. The crowd sits, quiet and expectant. Hundreds of fans open and snap in the sweltering heat, fluttering like bird wings. My heart thuds painfully and Hector pats my arm reassuringly.

“He’ll be fine,” he murmurs.

I barely hear him. From within another dark tunnel—there are three leading out of the arena—the Morcego races forward like an enraged bull. Its ebony body shines bright, glowing with energy. Two ivory tusks trailing golden ribbons protrude from its toothy mouth, and its eyes are bright yellow and mesmerizing. Around its neck are flowers, fluttering delicately against the scales that are stronger than armor.

I can’t take my gaze off the beast.

I clutch at the cobbled tunnel wall of the arena entrance, fingers digging into the grooves. My chest is on fire, rising and falling too fast. The dress is a fist around my heart.

Hector leans close. “Zarela?”

I nod and breathe deeply, fighting to regain my composure. The dragon is wider and taller than Papá, but there’s determination in the flat line of his mouth. He’s never feared them. I thought he’d turn away from dragonfighting after Mamá died, but her death only made him angry. Instead of one show a month, we now host two. I worry Papá won’t stop fighting until all the dragons of Hispalia have been hunted down and dragged in front of him.

The dragon snaps its great jaws and rushes forward, shiny claws digging into the sand. Papá sidesteps the attack, and the capote’s fabric curls around the wind like a beckoning finger. The beast’s attention is on the red flash of cloth, and Papá knows it. He pulls a long, thin blade with his free hand, while launching the banner high into the air. The dragon jumps, jaws snapping, trying to reach for it. But its wings have been clipped, and it can only jump so high. The Morcego lands on the ground with a furious roar, and as the dust rises and then settles, Papá makes his move.

The banner hits the ground.

Papá’s blade sinks into the back of the dragon’s neck, at the tender skin unprotected by scales. The beast lets out a deafening howl and slumps sideways while the crowd jumps to their feet. I sag against the wall. He’s safe. Papá raises both hands in triumph, and then he bends forward, sticks out his left leg and moves his right arm in a wide arc high above his head. A traditional Hispalian bow. The famous bell rings again, heralding Papá’s victory.

The show is a success.

I can see it in the smiles of our patrons, I can hear it coming from Papá’s adoring fans, stomping their feet. Duty beckons, and I turn away from Papá and walk down the long tunnel and back into the prep room. A few of Mamá’s dresses are kept here, safe in an antique armoire. Every time I change, I’m greeted by a veritable rainbow of sequins, ruffles, and lace, each tied to a memory of my mother. Sometimes I can smell the gardenias clinging to her hair, feel the hot flash of her temper, see her quick smile. I decide to remain in her red flamenco dress to send off our patrons instead of changing.

Paying customers will stream into the main foyer, twittering with excitement and the rush of seeing a live dragon up close. They’ll want to meet Papá and me, and I hurry to the main hall.

Heat floods into the great receiving room from the open entrance to the avenue and sweat glides down the back of my neck. Dozens of fat, squat candles delicately scented with gardenia petals illuminate the wrought iron chandelier. Servers carry trays laden with thinly sliced jamón and hard goat cheese, bowls of roasted marcona almonds, and olives marinated in olive oil, thyme, rosemary, and lemon, and porcelain pitchers filled with summer-touched wine, flavored with thick slices of golden apples and strawberries.

The tall, wooden double doors are flung open, perfectly centered to the grand red velvet staircase that splits halfway to the second floor, and then leads up in each direction to a balcony overlooking the foyer. The second floor has several entrances opening to long corridors wallpapered in red velvet that lead to the stone benches encircling the arena.

Once the dragon has been carried off to be butchered and Papá is done with charming the crowd, everyone will come down the stairs and I’ll be waiting for them, wearing a gardenia and a smile. I grab a glass of sangría and enjoy several sips, doing my best to ignore the sound of the mob protesting dragonfighting outside La Giralda. They march up and down the avenue with their banners and self-righteous attitudes. As if dragons don’t attack the cities of Hispalia, as if the monsters don’t terrorize people on their journey from one town to another. Traveling to the coast isn’t simple for Hispalians, not when we have to bring guards to fight off a potential attack from the skies. I take another long sip and pull an apple slice into my mouth when a sudden noise startles me.

Bloodcurdling screams enflame the air.

I whip around.

It came from the arena.

I rush from the doors, full skirt swirling, and race back the way I came. The guards are at my heels, swords drawn. More screams ring loudly in my ears, the sound reverberating and crashing against the stone walls. My hands are sweating by the time I make it to one of the arena entrances. I don’t recognize the people rushing past—blurs, all of them, some finely dressed, others in simple tunics and trousers. Their faces are carved in stark terror.

I clutch at a man’s sleeve. “What’s happened?”

He spins to face me, dark eyes frantic. A bloody gash mars his forehead. “Get away from the arena!”

“¿Qué? Señor, por favor—”

He yanks free and follows the crowd. I scramble away, shoving people as if I carried a sword and not a delicate fan, until I finally reach the arched entrance. I stop at the sight before me, sand kicking up at my heels.

On the pale floor of the arena, bodies lay in bloody heaps, staining the ground a deep rose red as people frantically try to flee the ring. My stomach lurches, and acid rises at the back of my throat.

Above, our dragons fly free, swooping and diving, claws out.

My hands fly to my mouth. The monsters are everywhere—racing between the rows of seats, chasing after patrons rushing out into the arena. They ought to be locked in the dungeons. I press against the curved wall, needing the strength of the stone to keep me upright.

¿Dónde está Papá?

I can’t see him anywhere, not through the mess of people fleeing into the tunnels, pushing and shoving. Others are trying to drag the wounded away from one of the Morcegos. I search for our five dragon tamers.

I know they’re out here; they have to be.

Except everyone is covered in sand, in blood, in ash. Faces blend together, features hard to distinguish. At last my gaze snags onto one of our tamers—Marco—dressed in black leather from head to toe, wielding blades and whips. He fights off one of the beasts, but the dragon roars and whips its tail, crashing against his chest. The force of the hit sends him flying, and he smashes against the arena wall with a sickening crunch.

“¡Aquí!” I yell to the person closest to me. “Follow me!” I guide whoever I can to the nearest tunnel, the hem of my dress caked in bloody sand, when I stumble over something.

No, someone.

I fall to my knees next to a child-sized body, burned crisp, my nose and mouth full of smoke and fire. Pandemonium reigns in every corner of the arena.

No sight of Papá or Lola anywhere.

The deafening growls coming from the beasts make my head spin, as if I’m on a too-fast carriage ride, tumbling down a hill, spinning wildly and out of control. Someone knocks me sideways. I land on my stomach and sand blasts my face, creeping into my eyes, the corners of my mouth, and up my nose. I sneeze, spit out what I can, and then wipe my face with the ruffled collar of my dress. It’s beyond ruined.

Quickly, I scan the arena. How many monsters have escaped their pens? Dragon one—the Culebra—flies low near the opposite entrance. Dragons two and three—both Rancios, crawl thirty feet from me, emitting an awful stench, like spoiled milk. In the distance, I catch sight of three more, our newest, soaring into the air.

We hadn’t bound their wings yet.

The sand around my hands darkens, the heat of the sun momentarily blocked. Warm gusts of air whips at my hair. I slowly glance up. Through the curling smoke a shadow looms from above. My stomach lurches.

The Morcego.

The deadliest dragon we own. Great bat wings, shiny black scales, and the ability to breathe fire, furious like an enraged bull readying to charge. Two great horns are on either side of its nostrils. His jaw opens, and the telltale crackling noise follows.

“Zarela!” someone roars. Papá’s face hovers inches from mine, his lips twisting in horror. He drags me to my feet as the beast blasts us with fire and smoke. Papá whips me around, and I feel him shuddering from the scorching hit. He screams into my ear as his clothes, his flesh, burst into flames. We stumble into the corridor, away from the carnage and the roiling mess of people facing a terrible, furious death. The scent of his charred skin makes acid rise up my throat.

It hurts to talk. My mouth is dry and filled with smoke. “¿Estás bien?” My steps fumble. I want to see how badly he’s hurt.

“Don’t slow down, hija!”

We race along the tunnel, the small space thick with the sound of people yelling for their loved ones. Everyone is dusty, covered in grime and stained with blood. Guilt slams into me, followed by a profound sense of shame. We’re responsible for all these people. How did this happen?

How will we survive this?

Dread pools deep in my belly as we get to the main foyer, filled with patrons. Time seems to jump forward, crosses miles in the space of a blink. Ticket holders flee La Giralda, rushing out the front door and escaping onto safer ground. It takes everything in me to hold it together.

Beside me, Papá drags his feet. His olive skin is nearly bleached of color. He sags against me, coughing loudly.

I stumble from his weight. “Papá!” He pitches forward, and my body shudders in alarm. “Papá!”

He crashes to his knees. I’m barely fast enough to keep him from breaking his nose. I grip his tattered jacket and slow his descent to the ground. Tears blur my vision. Slowly, I peel away the fabric and he groans. The upper right portion of his back and shoulder is a mess of bubbling and seared flesh. The blast missed his heart, but the wound is severe, blackened and smoking in some areas.

The roar surrounding me seems to drop to a hush. All I can hear are the sounds of my breathing; all I can see is my father’s unconsciousness. Dimly, I hear someone yelling my name.

“Zarela, gracias a Dios,” Lola exclaims when she reaches me, dropping to her knees. Her face turns ashen when it lands on my father’s wounds. “I’m going to send for the Gremio de los Sanadores. We need healers.” Her gaze wanders over my shoulder, taking in the many people moaning and begging for help. “Lots of them.”

I look around, despair rising. There’s still so much to do. All these people need to be moved out of La Giralda and taken to the Gremio de Sanadores, the local hospital run by healers. How many of them will survive? How many of them died?

I’m afraid of the answer.

“I’ll ask them to bring members who can help transport the wounded,” Lola adds, and then grimaces. “Those who can be moved, anyway.”

She’s right. Some people are too injured to be moved and will have to be treated here.

“Go, and hurry.” Everywhere I look, people are huddled into themselves, in shock, covered in bloody gashes and sooty clothes.

“I’ll be as quick as I can,” Lola says, jumping to her feet. Dirt and sweat stains streak her tunic, and her leather sandals are caked in sand. Someone steps in her path before she can leave. He’s tall with dark hair bound in a messy knot at the nape of his neck, his rich black skin shines with sweat, as if he’d come running. Warm brown eyes latch onto my maid. He wears the typical all gray ensemble preferred by the Gremio de Magia, the only flash of color coming from the vibrant embroidered patch sewn onto his long tunic, depicting an intricate crest made up of a wand and a grouping of stars.

Guillermo, the aspiring mago and apprentice at the Gremio de Magia.

“Do you have something I can give my father?” I ask him. He tears his attention off Lola and glances past me to Papá.

His lips twist in horror at the sight of my father’s mangled body. “Lo siento—I’m no healer—”

“Is there nothing you can do?” I know it’s unfair to ask him. Wizards and witches specialize in different kinds of magic, and some work closely with healers to create tinctures and tonics that push the body toward miraculous healing. The spells are costly, rare, and hardly ever on the market. Not unless you have connections.

Guillermo thrusts his hands into his tunic pocket and pulls out a thin wand. The wood has been dipped in a magical potion and has enough power for one use. Snap it in half, and the spell is released.

“All I have is a cooling spell,” he says. “I get so hot waiting for the fight to end—”

He must see my disappointment written all over my face because he breaks off.

“Your father needs a healer,” Lola says. “I’ll run now—”

“I’ll go with you—” Guillermo interrupts, clearly relieved.

She rushes away, the apprentice at her heels, both nimbly skirting around the wounded.

My mind crowds with one worry after another. The questions I crave answers to make my neck tighten. How did the dragons escape? Where are they now? What will happen to La Giralda?

“Señorita Zarela,” someone says from behind me.

It’s one of the housemaids, holding out a bottle filled with pressed aloe vera. Every arena must have supplies in case the worst should happen, stored in the required infirmary on site. Over the years, my parents have needed various treatments due to some scrapes and ailments while dancing under a hot sun or fighting dragons. Nothing serious, but the room always has bottles of tincture to help with minor burns, sore heels, and the like.

I blink as realization dawns. There’re blankets and cots in that room, and a few potted herbs too. “Gracias, Antonia,” I say, taking the medicine. “Will you please direct the staff to hand out as much of the supplies as people need?”

She rushes off to do my bidding.

“There you are!” Hector’s booming voice calls as he strides forward, arms spread wide. Relief blooms in my chest. I dart into his embrace, pressing my cheek hard against his fine jacket. He stiffens, and I step back.

Sections of his jacket are scorched. “You’re hurt.”

“Not terribly,” he says. “Just don’t squeeze me too hard.”

“Tío,” I say. “Mi papá—”

Hector’s eyes widen in alarm.

I gesture toward the ground. “Look at him.”

Hector’s lips thin to a pale slash. Then he beckons to someone sprinting past us, asking for help to move Papá to the infirmary. The other man agrees, and together they gingerly carry my father to the small room adjacent to the prep room. I move to follow inside, but Hector shakes his head. “Zarela, you must take care of the others. I have your father now.”

“But—”

“Let me help you,” he says quietly.

I look past him, at the prone figure of my father lying on his stomach. He’s still but for the gentle movement of his back, rising and falling. “I’ll send a healer to you as soon as they arrive.”

Hector sends me away. My footsteps are heavy against the cold stone floor, and it’s taking everything in me to keep my back straight, the guilt heavy on my shoulders. As soon as I return to the grand foyer, I hear my name coming from every direction, people needing salves and bandages and healers, but my mind narrows onto one blinding thought.

How did this happen?

Dragonadores die frequently in the fights—but the dragon is quickly captured and killed by tamers. It’s what should have happened today—but there were too many monsters to contain, and our tamers died trying.

Hot shame rises, enflaming my cheeks.

I run around, handing out supplies and small jars of expensive burn ointment. I hand out whatever we have left on our shelves, cost be damned. Sweat beads at my hairline as I walk around the foyer, sidestepping the dozens of blankets and cots strewn everywhere.

“Señorita Zarela?”

The voice at my elbow jerks me from my thoughts. I turn to face Benito, one of our dragon tamers, his protective mask off, and his black leather ensemble half covered in dragon blood. He has an angular, sharp face with deep, weathered lines forged by years in the sun and taming beasts. “¿Tienes un momento, por favor?”

“Give me an update, Benito.”

The lines at the corners of his eyes tighten. “I don’t have an accurate number on how many people were injured, señorita. My guess is close to fifty, perhaps up to seventy.” I wince and try to swallow, but my throat thickens painfully. He shifts on his feet, clearly ill at ease. “We’ve lost thirteen patrons, including an eight-year-old boy and a senior member of the Gremio.”

My lips part. I turn over his words as if they’re a nightmare and I’m desperate to wake up.

Benito clutches his leather whip tighter. “With your permission, I’d like to order most of your guards to help the wounded home.”

“Of course,” I murmur, surprised I can hear his words at all over my roaring heartbeat.

“As for your dragons—” He pauses, and I brace myself for the worst. Dragons are expensive investments. “Three dragons never left their pens,” he says, counting with his fingers. “The last three are restrained and bound in the arena, while three others have flown.”

My stomach swoops as a sudden, horrifying thought slams into me—the dragons that flew away will wreak havoc over Santivilla, scorching people, burning homes. “Is there any way we can retrieve them? Can you arrange a group of our tamers—” My voice breaks off at his crestfallen face.

“I am the only surviving one, Señorita Zarela.” His next words are kind, kinder than I deserve. “At this point, there is no way to know where the beasts have gone. Would you try to find a pet bird that’s escaped its cage? The dragons flew high and away from the city center. They might never return. I believe the best course is for me to remain with the other dragons down below.”

His logic is sound, but I can’t help worrying about an attack on the city. “Benito, how did this happen? How did our other dragons escape their pens?”

He frowns. “I found something strange. I think—”

“Zarela!”

Benito and I turn as Lola runs up to us, hair windblown, tunic untucked from her ruffled skirt. Dirt smudges both cheeks, and her eyes look wild. Guillermo isn’t with her.

She stops abruptly, panting, and then clutches her side. “I am not built for running.”

“Lola,” I say, fighting to keep my voice calm. “What is it?”

“I’ve brought the healers, and they’re with your father.” Her next words come out shaky. “They said to come quick.”

Years ago, my mother and I were practicing one of her routines, until the sun had dipped far under Santivilla’s skyline. She demanded a lot, and I gave her everything I had for the chance to be like her. Mamá could have danced all day and done the same all over again on the next, but I struggled to keep up with her energy, her vitality. Her routines always stole my breath. Made my legs shake, and my chest rise and fall too fast.

Lola’s words send me into the same state.

She seems to understand, because she immediately grabs one of my arms and helps me take the first step. Since the day Mamá died, I circled around my father, trying to protect him from any and all imagined dangers that might take him away from me. But he refused to quit the one thing I feared the most. Being a Dragonador has claws that have sunk deep into his flesh.

I gave up fighting him months ago. Foolish, deadly mistake.

“Will he live?” I ask through numb lips.

She squeezes me gently. “No lo sé.”

Of course she wouldn’t know.

We walk through the mess in the foyer, the iron chandelier lit with guttering candles, illuminating the room in a soft glow. I didn’t realize the sun had gone down. The wounded who couldn’t possibly leave La Giralda are situated on cots and blankets, surrounded by their friends and family—friends and family who glare as I stumble along to our infirmary. I feel their anger as if it were a blade in the back. It’s no less than I deserve.

A healer waits outside the door, impatient, booted feet fidgeting. She’s austere and grave, but I detect something else from that awful twist to her mouth. She’s petite with deep black skin and a no-nonsense gaze, and wearing a simple blue tunic and skirt, her healer’s linen clothing stained with far too much blood.

Papá’s blood.

“Señorita Zarela.” The healer nods once. “I’m Eva.”

I lick my dry lips. “How is he?”

“He’s awake,” she says. “And raving. He’s refusing my assistance, ordering me from the room. I can’t work on him like this.”

Relief courses up and down my body. Papá is alive. “Let me see him.”

“There’s more,” she says. “The wound near his upper shoulder is deep, and I’m worried about infection. I must remove all the blackened skin.” She hesitates. “It will mean that he’ll no longer be able to move his arm higher than the level of his heart.”

I blink, understanding dawning.

“I’m sure that’s fine. Right, Zarela?” Lola asks. “Better to remove the”—she blanches—“dead skin?”

It’s not the least bit fine. Without full mobility, my father will not win a fight against a dragon.

His Dragonador days are over.

It’s what I want. And yet . . . Being Santiago Zalvidar the Dragonador is more important to him than anything else. More important than being a husband or a father. Papá will never forgive me if I don’t do everything I can to help him hold onto his dream.

And I don’t want to live in a world without him in it.

“Find another way,” I say in a hard voice. “Find the right procedure. I don’t care about the cost. Bring in a wizard if you have to.”

Lola shoots me a look, dark brows rising.

“There is none,” the healer says coolly. “If I don’t remove parts of his shoulder and arm, he’ll succumb to infection. He’ll die in a matter of days.”

There’s a horrible silence, and I’m perfectly aware I have to fill it with my answer, but the words are stuck at the back of my throat.

“I can’t proceed without permission,” she says. “I’m dealing with a member of the Gremio de Dragonadores, and I fear retribution for permanently ending the famous Santiago Zalvidar’s career.”

Finally, I’m able to speak, even if it’s hardly a whisper. “I’ll speak with him.”

I untangle myself from Lola and enter the infirmary, quickly shutting the heavy wooden door behind me. Papá lies on his belly on the narrow bed, and at the sight of his scorched back, my stomach lurches. It’s a mess of bubbling skin, and mottled, dying flesh the color of night.

He acted quickly and saved me. His reward will be to lose his arena, his inheritance, a profession he loves, and maybe his life.

What is La Giralda without its famous Dragonador?

Papá raises his head and spears me with a heated look from his bloodshot eyes. He’s been crying. My proud father, who’s fought over one hundred dragons, lost the love of his life, reduced to tears.

“Zarela,”he says hoarsely. “Don’t let them ruin me. Do you hear me?”

I take a step forward. “Papá—”

His expression darkens, the lines across his forehead deepening. “Do not let them touch me.”

“I can’t do that,” I say, fighting to keep my tone measured. “Papá, you must let her do the work.”

“There has to be another way!” he roars, and I flinch as the sound whips around me, trapping me in his fury.

“You’ll die if she doesn’t rid the dead flesh.” My voice breaks. “Do you understand?”

“Find a bruja.” Papá slams his fist against the cot and he howls—in pain, frustration, I can’t tell. He’s panting, breaths coming in and out too fast. “That hurt, Dios.”

“Papá,” I say, rushing forward, but by the time I’ve reached his side, he’s passed out again.

“Eva!” I yell.

The door opens with a snap, and she strides in, two others at her elbow. “Do I have permission?”

I swallow hard, unable to look away from my father. His lips are bent into a grimace. Even while sleeping, the pain won’t leave.

“Señorita?” Eva asks, this side of impatient. “I have to move quickly if I’m to save him.”

“I must pay a visit to the Gremio de Magia. Perhaps they might be able to help him with an encanto.”

“A spell?” Eva repeats. “A custom spell that will cure him will take days to prepare. Your father doesn’t have that kind of time.”

“Are you sure?”

She regards me in offended silence. I thread my hands through my messy hair, breathing hard, knowing what I’ll say but dreading it. He will hate what I’ve done when he wakes up. I can live with that. I can’t, however, live without him.

I lift my chin. “Do what you have to do.”

Lola follows me as I make my way back to the foyer. I’m about to veer toward the kitchen when a shout comes from the direction of the great double doors. Lola and I turn in time to see a black, four-wheeled carriage pulled by six horses stop in front of La Giralda. I stiffen against her, dread sinking into the marrow of my bones.

“Dragonador Gremio members,” I say under my breath. I walk up to the entrance, head held high and wait for the group at the top of the marble steps.

I hope these are Papá’s friends, and I pray the Dragon Master hasn’t shown up himself. This is one man my father hasn’t been able to charm.

But my prayer is dashed in the next instant.

A tall, broad-shouldered man climbs out of the gilded carriage, the moonlight casting him in a delicate silver hue. His olive skin is stretched and weathered, resembling a leather hat left too long in the sun.

Don Eduardo Del Pino.

Nothing escapes his attention. I lift my chin as my knees start trembling. This man holds our fate in his hands—and he can’t stand my father. Papá has never explained why. He rarely comes to our arena. Mamá was still alive during his last visit.

I swallow hard, fighting to keep my panic at bay. Something of this magnitude can’t be postponed.

Papá and I have much to answer for.

“Do you want me to stay with you?” Lola asks.

I shake my head. “Will you find Ofelia? Ask her to prepare bone broth for the wounded.”

“What about a torta instead?” she asks with a hint of a smile.

I sigh wearily. “Yes, I think we all need cake.”

She’s gone before I can tell her I didn’t mean it. I don’t deserve cake.

Slowly, I turn and look down at the Dragon Master, accompanied by two other Gremio members. The three caballeros march up the marble steps to greet me. They’re all dressed in matching, somber black trousers and coats, embroidered with white thread in the shape of various dragons. Their boots are adorned with brass buckles, and the worn brown leather almost reaches the knee. Around their necks is an unwrapped linen scarf the color of blood, stitched with the name of the Gremio. An ornate brooch, gold and shaped into a crest with a pair of interlocking dragons, completes the ensemble.

I incline my head toward the Conde. “Hola, Don Eduardo.”

“Señorita Zalvidar.” He has the kind of voice that could send children running. A hard rasp, filled with smoke and snarl, and hard-earned from years of fighting monsters. “One of your patrons notified me of today’s disaster.”

There’s clear reproach in his tone. I should have sent word to the Gremio, but I’d forgotten.

The Dragon Master brushes past and stops under the doorframe. The others quickly follow with sharp exclamations. Seeing the wake of destruction through their eyes brings the experience of it fresh to my mind. The flames. Mauled, burning bodies. Bloody sand everywhere.

“How did this happen?” the Dragon Master demands.

I shake my head, numb. “I don’t have a suitable answer. It’s been chaotic—”

“That is unacceptable.”

I fall silent, my cheeks flushing. Humiliation burns.

“¿Y tu Papá?” one of Eduardo’s companions asks, scanning the room. He’s shorter than all of them, with a round belly. “How is he?”

I hesitate. “He’s with a healer.”

Don Eduardo studies me for a moment, leaning more heavily onto his black cane with the head of a dragon. “Will he live?” he rasps, voice yielding not an ounce of sympathy.

“Con la ayuda de Dios,” I say.

“With God’s help,” he says. My father is the most respected Dragonador in all of Hispalia, and the Dragon Master can’t offer a glimpse of concern. “Qué tragedia,” he says. “And the arena?”

* * *

In the smoldering ruin that once showcased our imported white sand, the stone is scorched, and deep fissures have left their permanent mark. Huge chunks of the sand in the arena are a bloody, congealed mess. Three dragons are bound by a massive chain.

“Where did you get them?” one of the members asks.

“From the same place as the other rings in town,” I say stiffly. These dragons can be found anywhere in Hispalia, in the desert plains to the north, in watery caves to the east. Like cockroaches, they multiply without any constraint, invading even the most unlikely of places. They’re easily hunted and kept in ranches where they can be purchased for dragonfighting.

“We have to kill the line,” the Conde says grimly. He half lifts a finger. “All three of them must die for what they’ve done, along with their mothers.”

I flinch. Six dragons, six investments gone in one afternoon.

There’s been too much death on this day.

The Conde strides forward and unsheathes his long blade. He sinks the sword deep in the muscle at the back of the neck, piercing the lungs. The deaths are quick. Over and done with, but the sound of their choked cries slam into my body like a physical blow to the face. Puddles of blood reach across the arena like gnarly tree roots.

The guild members regard the destruction of the building in silence for a long moment. They’re grim and disapproving, and their sudden quiet sends a flicker of unease down my spine. The guards have brought down the victims, and they lie next to the opposite entrance, covered in sheets. Tomorrow, I’ll arrange for their families to retrieve them. I make a note to send money for the funeral arrangements.

The Dragon Master regards the dead.

“The Gremio will stand with us, won’t they?” I ask, unable to help myself. We are the most popular ring in Hispalia. Five hundred years of success and fame and legend. We’ve never had an incident before now.

No one responds to this, and my face drains of all color.

Eduardo sheaths his sword. His feathery white brows pull into a tight frown. “This event will not go unpunished. I’ll send a summons for your father. Don’t let him miss it.”

“What’s going to happen to La Giralda?” I ask, worry edging into my voice.

The Dragon Master levels me with a stern glare, and then he walks off, the other members quickly following. They leave me standing in the middle of the bloody arena, amidst the scorched stone and death.

I