What the Moon Saw

What the Moon SawPREFACE.What the Moon SawTHE STORY OF THE YEAR.SHE WAS GOOD FOR NOTHING."THERE IS A DIFFERENCE."EVERYTHING IN ITS RIGHT PLACE.THE GOBLIN AND THE HUCKSTER.IN A THOUSAND YEARS.THE BOND OF FRIENDSHIP.JACK THE DULLARD.SOMETHING.UNDER THE WILLOW TREE.THE BEETLE.WHAT THE OLD MAN DOES IS ALWAYS RIGHT.THE WIND TELLS ABOUT WALDEMAR DAA AND HIS DAUGHTERS.OLE THE TOWER-KEEPER.GOOD HUMOUR.A LEAF FROM THE SKY.THE DUMB BOOK.THE JEWISH GIRL.THE THORNY ROAD OF HONOURTHE OLD GRAVESTONETHE MARSH KING'S DAUGHTER.THE LAST DREAM OF THE OLD OAK TREE.THE BELL-DEEP.THE PUPPET SHOWMAN.THE PIGS.ANNE LISBETH.CHARMING.THE GIRL WHO TROD ON THE LOAF.A STORY FROM THE SAND-DUNES.THE BISHOP OF BÖRGLUM AND HIS WARRIORS.THE SNOW MAN.TWO MAIDENS.THE PEN AND INKSTAND.SOUP ON A SAUSAGE-PEG.THE STONE OF THE WISE MEN.THE BUTTERFLY.THE PHŒNIX BIRD.THE CHILD IN THE GRAVE.Copyright

What the Moon Saw

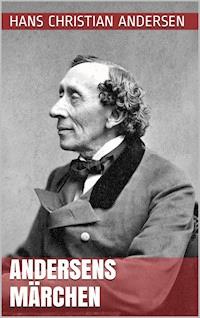

Hans Christian Andersen

PREFACE.

The present book is put forth as a sequel to the volume of

Hans C. Andersen's "Stories and Tales". It contains tales and

sketches various in character; and following, as it does, an

earlier volume, care has been taken to intersperse with the

children's tales stories which, by their graver character and

deeper meaning, are calculated to interest those "children of a

larger growth" who can find instruction as well as amusement in the

play of fancy and imagination, though the realm be that of fiction,

and the instruction be conveyed in a simple form.The series of sketches of "What the Moon Saw," with which the

present volume opens, arose from the experiences of Andersen, when

as a youth he went to seek his fortune in the capital of his native

land; and the story entitled "Under the Willow Tree" is said

likewise to have its foundation in fact; indeed, it seems redolent

of the truth of that natural human love and suffering which is so

truly said to "make the whole world kin."

What the Moon Saw

It is a strange thing, that when I feel most fervently and

most deeply, my hands and my tongue seem alike tied, so that I

cannot rightly describe or accurately portray the thoughts that are

rising within me; and yet I am a painter: my eye tells me as much

as that, and all my friends who have seen my sketches and fancies

say the same.I am a poor lad, and live in one of the narrowest of lanes;

but I do not want for light, as my room is high up in the house,

with an extensive prospect over the neighbouring roofs. During the

first few days I went to live in the town, I felt low-spirited and

solitary enough. Instead of the forest and the green hills of

former days, I had here only a forest of chimney-pots to look out

upon. And then I had not a single friend; not one familiar face

greeted me.So one evening I sat at the window, in a desponding mood; and

presently I opened the casement and looked out. Oh, how my heart

leaped up with joy! Here was a well-known face at last—a round,

friendly countenance, the face of a good friend I had known at

home. In, fact it was the Moon that looked in upon me. He was quite

unchanged, the dear old Moon, and had the same face exactly that he

used to show when he peered down upon me through the willow trees

on the moor. I kissed my hand to him over and over again, as he

shone far into my little room; and he, for his part, promised me

that every evening, when he came abroad, he would look in upon me

for a few moments. This promise he has faithfully kept. It is a

pity that he can only stay such a short time when he comes.

Whenever he appears, he tells me of one thing or another that he

has seen on the previous night, or on that same evening. "Just

paint the scenes I describe to you"—this is what he said to me—"and

you will have a very pretty picture-book." I have followed his

injunction for many evenings. I could make up a new "Thousand and

One Nights," in my own way, out of these pictures, but the number

might be too great, after all. The pictures I have here given have

not been chosen at random, but follow in their proper order, just

as they were described to me. Some great gifted painter, or some

poet or musician, may make something more of them if he likes; what

I have given here are only hasty sketches, hurriedly put upon the

paper, with some of my own thoughts interspersed; for the Moon did

not come to me every evening—a cloud sometimes hid his face from

me.First Evening."Last night"—I am quoting the Moon's own words—"last night I

was gliding through the cloudless Indian sky. My face was mirrored

in the waters of the Ganges, and my beams strove to pierce through

the thick intertwining boughs of the bananas, arching beneath me

like the tortoise's shell. Forth from the thicket tripped a Hindoo

maid, light as a gazelle, beautiful as Eve. Airy and ethereal as a

vision, and yet sharply defined amid the surrounding shadows, stood

this daughter of Hindostan: I could read on her delicate brow the

thought that had brought her hither. The thorny creeping plants

tore her sandals, but for all that she came rapidly forward. The

deer that had come down to the river to quench their thirst, sprang

by with a startled bound, for in her hand the maiden bore a lighted

lamp. I could see the blood in her delicate finger tips, as she

spread them for a screen before the dancing flame. She came down to

the stream, and set the lamp upon the water, and let it float away.

The flame flickered to and fro, and seemed ready to expire; but

still the lamp burned on, and the girl's black sparkling eyes, half

veiled behind their long silken lashes, followed it with a gaze of

earnest intensity. She knew that if the lamp continued to burn so

long as she could keep it in sight, her betrothed was still alive;

but if the lamp was suddenly extinguished, he was dead. And the

lamp burned bravely on, and she fell on her knees, and prayed. Near

her in the grass lay a speckled snake, but she heeded it not—she

thought only of Bramah and of her betrothed. 'He lives!' she

shouted joyfully, 'he lives!' And from the mountains the echo came

back upon her, 'he lives!'"Second Evening."Yesterday," said the Moon to me, "I looked down upon a small

courtyard surrounded on all sides by houses. In the courtyard sat a

clucking hen with eleven chickens; and a pretty little girl was

running and jumping around them. The hen was frightened, and

screamed, and spread out her wings over the little brood. Then the

girl's father came out and scolded her; and I glided away and

thought no more of the matter."But this evening, only a few minutes ago, I looked down into

the same courtyard. Everything was quiet. But presently the little

girl came forth again, crept quietly to the hen-house, pushed back

the bolt, and slipped into the apartment of the hen and chickens.

They cried out loudly, and came fluttering down from their perches,

and ran about in dismay, and the little girl ran after them. I saw

it quite plainly, for I looked through a hole in the hen-house

wall. I was angry with the wilful child, and felt glad when her

father came out and scolded her more violently than yesterday,

holding her roughly by the arm: she held down her head, and her

blue eyes were full of large tears. 'What are you about here?' he

asked. She wept and said, 'I wanted to kiss the hen and beg her

pardon for frightening her yesterday; but I was afraid to tell

you.'"And the father kissed the innocent child's forehead, and I

kissed her on the mouth and eyes."Third Evening."In the narrow street round the corner yonder—it is so narrow

that my beams can only glide for a minute along the walls of the

house, but in that minute I see enough to learn what the world is

made of—in that narrow street I saw a woman. Sixteen years ago that

woman was a child, playing in the garden of the old parsonage, in

the country. The hedges of rose-bush were old, and the flowers were

faded. They straggled wild over the paths, and the ragged branches

grew up among the boughs of the apple trees; here and there were a

few roses still in bloom—not so fair as the queen of flowers

generally appears, but still they had colour and scent too. The

clergyman's little daughter appeared to me a far lovelier rose, as

she sat on her stool under the straggling hedge, hugging and

caressing her doll with the battered pasteboard

cheeks."Ten years afterwards I saw her again. I beheld her in a

splendid ball-room: she was the beautiful bride of a rich merchant.

I rejoiced at her happiness, and sought her on calm quiet

evenings—ah, nobody thinks of my clear eye and my silent glance!

Alas! my rose ran wild, like the rose bushes in the garden of the

parsonage. There are tragedies in every-day life, and to-night I

saw the last act of one."She was lying in bed in a house in that narrow street: she

was sick unto death, and the cruel landlord came up, and tore away

the thin coverlet, her only protection against the cold. 'Get up!'

said he; 'your face is enough to frighten one. Get up and dress

yourself, give me money, or I'll turn you out into the street!

Quick—get up!' She answered, 'Alas! death is gnawing at my heart.

Let me rest.' But he forced her to get up and bathe her face, and

put a wreath of roses in her hair; and he placed her in a chair at

the window, with a candle burning beside her, and went

away."I looked at her, and she was sitting motionless, with

her hands in her lap. The wind caught the open window and shut it

with a crash, so that a pane came clattering down in fragments; but

still she never moved. The curtain caught fire, and the flames

played about her face; and I saw that she was dead. There at the

open window sat the dead woman, preaching a sermon againstsin—my poor faded rose out of the

parsonage garden!"Fourth Evening."This evening I saw a German play acted," said the

Moon. "It was in a little town. A stable had been turned into a

theatre; that is to say, the stable had been left standing, and had

been turned into private boxes, and all the timber work had been

covered with coloured paper. A little iron chandelier hung beneath

the ceiling, and that it might be made to disappear into the

ceiling, as it does in great theatres, when theting-tingof the prompter's bell is

heard, a great inverted tub had been placed just above

it."'Ting-ting!' and

the little iron chandelier suddenly rose at least half a yard and

disappeared in the tub; and that was the sign that the play was

going to begin. A young nobleman and his lady, who happened to be

passing through the little town, were present at the performance,

and consequently the house was crowded. But under the chandelier

was a vacant space like a little crater: not a single soul sat

there, for the tallow was dropping, drip, drip! I saw everything,

for it was so warm in there that every loophole had been opened.

The male and female servants stood outside, peeping through the

chinks, although a real policeman was inside, threatening them with

a stick. Close by the orchestra could be seen the noble young

couple in two old arm-chairs, which were usually occupied by his

worship the mayor and his lady; but these latter were to-day

obliged to content themselves with wooden forms, just as if they

had been ordinary citizens; and the lady observed quietly to

herself, 'One sees, now, that there is rank above rank;' and this

incident gave an air of extra festivity to the whole proceedings.

The chandelier gave little leaps, the crowd got their knuckles

rapped, and I, the Moon, was present at the performance from

beginning to end."

Fifth Evening."Yesterday," began the Moon, "I looked down upon the turmoil

of Paris. My eye penetrated into an apartment of the Louvre. An old

grandmother, poorly clad—she belonged to the working class—was

following one of the under-servants into the great empty

throne-room, for this was the apartment she wanted to see—that she

was resolved to see; it had cost her many a little sacrifice, and

many a coaxing word, to penetrate thus far. She folded her thin

hands, and looked round with an air of reverence, as if she had

been in a church."'Here it was!' she said, 'here!' And she approached the

throne, from which hung the rich velvet fringed with gold lace.

'There,' she exclaimed, 'there!' and she knelt and kissed the

purple carpet. I think she was actually weeping."'But it was notthis veryvelvet!' observed the footman, and a smile played about his

mouth. 'True, but it was this very place,' replied the woman, 'and

it must have looked just like this.' 'It looked so, and yet it did

not,' observed the man: 'the windows were beaten in, and the doors

were off their hinges, and there was blood upon the floor.' 'But

for all that you can say, my grandson died upon the throne of

France. Died!' mournfully repeated the old woman. I do not think

another word was spoken, and they soon quitted the hall. The

evening twilight faded, and my light shone doubly vivid upon the

rich velvet that covered the throne of France."Now, who do you think this poor woman was? Listen, I will

tell you a story."It happened, in the Revolution of July, on the evening of

the most brilliantly victorious day, when every house was a

fortress, every window a breastwork. The people stormed the

Tuileries. Even women and children were to be found among the

combatants. They penetrated into the apartments and halls of the

palace. A poor half-grown boy in a ragged blouse fought among the

older insurgents. Mortally wounded with several bayonet thrusts, he

sank down. This happened in the throne-room. They laid the bleeding

youth upon the throne of France, wrapped the velvet around his

wounds, and his blood streamed forth upon the imperial purple.

There was a picture! the splendid hall, the fighting groups! A torn

flag lay upon the ground, the tricolor was waving above the

bayonets, and on the throne lay the poor lad with the pale

glorified countenance, his eyes turned towards the sky, his limbs

writhing in the death agony, his breast bare, and his poor tattered

clothing half hidden by the rich velvet embroidered with silver

lilies. At the boy's cradle a prophecy had been spoken: 'He will

die on the throne of France!' The mother's heart dreamt of a second

Napoleon."My beams have kissed the wreath ofimmortelleson his grave, and this

night they kissed the forehead of the old grandame, while in a

dream the picture floated before her which thou mayest draw—the

poor boy on the throne of France."

Sixth Evening."I've been in Upsala," said the Moon: "I looked

down upon the great plain covered with coarse grass, and upon the

barren fields. I mirrored my face in the Tyris river, while the

steamboat drove the fish into the rushes. Beneath me floated the

waves, throwing long shadows on the so-called graves of Odin, Thor,

and Friga. In the scanty turf that covers the hill-side names have

been cut.[1]There is

no monument here, no memorial on which the traveller can have his

name carved, no rocky wall on whose surface he can get it painted;

so visitors have the turf cut away for that purpose. The naked

earth peers through in the form of great letters and names; these

form a network over the whole hill. Here is an immortality, which

lasts till the fresh turf grows![1]Travellers on the Continent have

frequent opportunities of seeing how universally this custom

prevails among travellers. In some places on the Rhine, pots of

paint and brushes are offered by the natives to the traveller

desirous of "immortalising" himself."Up on the hill stood a man, a poet. He emptied the mead horn

with the broad silver rim, and murmured a name. He begged the winds

not to betray him, but I heard the name. I knew it. A count's

coronet sparkles above it, and therefore he did not speak it out. I

smiled, for I knew that a poet's crown adorns his own name. The

nobility of Eleanora d'Este is attached to the name of Tasso. And I

also know where the Rose of Beauty blooms!"Thus spake the Moon, and a cloud came between us. May no

cloud separate the poet from the rose!

Seventh Evening."Along the margin of the shore stretches a forest

of firs and beeches, and fresh and fragrant is this wood; hundreds

of nightingales visit it every spring. Close beside it is the sea,

the ever-changing sea, and between the two is placed the broad

high-road. One carriage after another rolls over it; but I did not

follow them, for my eye loves best to rest upon one point. A Hun's

Grave[2]lies there,

and the sloe and blackthorn grow luxuriantly among the stones. Here

is true poetry in nature.[2]Large mounds similar to the "barrows"

found in Britain, are thus designated in Germany and the

North."And how do you think men appreciate this poetry? I will tell

you what I heard there last evening and during the

night."First, two rich landed proprietors came driving by. 'Those

are glorious trees!' said the first. 'Certainly; there are ten

loads of firewood in each,' observed the other: 'it will be a hard

winter, and last year we got fourteen dollars a load'—and they were

gone. 'The road here is wretched,' observed another man who drove

past. 'That's the fault of those horrible trees,' replied his

neighbour; 'there is no free current of air; the wind can only come

from the sea'—and they were gone. The stage coach went rattling

past. All the passengers were asleep at this beautiful spot. The

postillion blew his horn, but he only thought, 'I can play

capitally. It sounds well here. I wonder if those in there like

it?'—and the stage coach vanished. Then two young fellows came

gallopping up on horseback. There's youth and spirit in the blood

here! thought I; and, indeed, they looked with a smile at the

moss-grown hill and thick forest. 'I should not dislike a walk here

with the miller's Christine,' said one—and they flew

past."The flowers scented the air; every breath of air was hushed:

it seemed as if the sea were a part of the sky that stretched above

the deep valley. A carriage rolled by. Six people were sitting in

it. Four of them were asleep; the fifth was thinking of his new

summer coat, which would suit him admirably; the sixth turned to

the coachman and asked him if there were anything remarkable

connected with yonder heap of stones. 'No,' replied the coachman,

'it's only a heap of stones; but the trees are remarkable.' 'How

so?' 'Why, I'll tell you how they are very remarkable. You see, in

winter, when the snow lies very deep, and has hidden the whole road

so that nothing is to be seen, those trees serve me for a landmark.

I steer by them, so as not to drive into the sea; and you see that

is why the trees are remarkable.'"Now came a painter. He spoke not a word, but his eyes

sparkled. He began to whistle. At this the nightingales sang louder

than ever. 'Hold your tongues!' he cried testily; and he made

accurate notes of all the colours and transitions—blue, and lilac,

and dark brown. 'That will make a beautiful picture,' he said. He

took it in just as a mirror takes in a view; and as he worked he

whistled a march of Rossini. And last of all came a poor girl. She

laid aside the burden she carried, and sat down to rest upon the

Hun's Grave. Her pale handsome face was bent in a listening

attitude towards the forest. Her eyes brightened, she gazed

earnestly at the sea and the sky, her hands were folded, and I

think she prayed, 'Our Father.' She herself could not understand

the feeling that swept through her, but I know that this minute,

and the beautiful natural scene, will live within her memory for

years, far more vividly and more truly than the painter could

portray it with his colours on paper. My rays followed her till the

morning dawn kissed her brow."

Eighth Evening.Heavy clouds obscured the sky, and the Moon did not make his

appearance at all. I stood in my little room, more lonely than

ever, and looked up at the sky where he ought to have shown

himself. My thoughts flew far away, up to my great friend, who

every evening told me such pretty tales, and showed me pictures.

Yes, he has had an experience indeed. He glided over the waters of

the Deluge, and smiled on Noah's ark just as he lately glanced down

upon me, and brought comfort and promise of a new world that was to

spring forth from the old. When the Children of Israel sat weeping

by the waters of Babylon, he glanced mournfully upon the willows

where hung the silent harps. When Romeo climbed the balcony, and

the promise of true love fluttered like a cherub toward heaven, the

round Moon hung, half hidden among the dark cypresses, in the lucid

air. He saw the captive giant at St. Helena, looking from the

lonely rock across the wide ocean, while great thoughts swept

through his soul. Ah! what tales the Moon can tell. Human life is

like a story to him. To-night I shall not see thee again, old

friend. To-night I can draw no picture of the memories of thy

visit. And, as I looked dreamily towards the clouds, the sky became

bright. There was a glancing light, and a beam from the Moon fell

upon me. It vanished again, and dark clouds flew past; but still it

was a greeting, a friendly good-night offered to me by the

Moon.

Ninth Evening.The air was clear again. Several evenings had passed, and the

Moon was in the first quarter. Again he gave me an outline for a

sketch. Listen to what he told me."I have followed the polar bird and the swimming whale

to the eastern coast of Greenland. Gaunt ice-covered rocks and dark

clouds hung over a valley, where dwarf willows and barberry bushes

stood clothed in green. The blooming lychnis exhaled sweet odours.

My light was faint, my face pale as the water lily that, torn from

its stem, has been drifting for weeks with the tide. The

crown-shaped Northern Light burned fiercely in the sky. Its ring

was broad, and from its circumference the rays shot like whirling

shafts of fire across the whole sky, flashing in changing radiance

from green to red. The inhabitants of that icy region were

assembling for dance and festivity; but, accustomed to this

glorious spectacle, they scarcely deigned to glance at it. 'Let us

leave the souls of the dead to their ball-play with the heads of

the walruses,' they thought in their superstition, and they turned

their whole attention to the song and dance. In the midst of the

circle, and divested of his furry cloak, stood a Greenlander, with

a small pipe, and he played and sang a song about catching the

seal, and the chorus around chimed in with, 'Eia,

Eia, Ah.' And in their white furs they danced

about in the circle, till you might fancy it was a polar bear's

ball."And now a Court of Judgment was opened. Those

Greenlanders who had quarrelled stepped forward, and the offended

person chanted forth the faults of his adversary in an extempore

song, turning them sharply into ridicule, to the sound of the pipe

and the measure of the dance. The defendant replied with satire as

keen, while the audience laughed, and gave their verdict. The rocks

heaved, the glaciers melted, and great masses of ice and snow came

crashing down, shivering to fragments as they fell: it was a

glorious Greenland summer night. A hundred paces away, under the

open tent of hides, lay a sick man. Life still flowed through his

warm blood, but still he was to die—he himself felt it, and all who

stood round him knew it also; therefore his wife was already sowing

round him the shroud of furs, that she might not afterwards be

obliged to touch the dead body. And she asked, 'Wilt thou be buried

on the rock, in the firm snow? I will deck the spot with thykayak, and thy arrows, and theangekokkshall dance over it. Or

wouldst thou rather be buried in the sea?' 'In the sea,' he

whispered, and nodded with a mournful smile. 'Yes, it is a pleasant

summer tent, the sea,' observed the wife. 'Thousands of seals sport

there, the walrus shall lie at thy feet, and the hunt will be safe

and merry!' And the yelling children tore the outspread hide from

the window-hole, that the dead man might be carried to the ocean,

the billowy ocean, that had given him food in life, and that now,

in death, was to afford him a place of rest. For his monument, he

had the floating, ever-changing icebergs, whereon the seal sleeps,

while the storm bird flies round their gleaming

summits!"

Tenth Evening."I knew an old maid," said the Moon. "Every winter she wore a

wrapper of yellow satin, and it always remained new, and was the

only fashion she followed. In summer she always wore the same straw

hat, and I verily believe the very same grey-blue

dress."She never went out, except across the street to an old

female friend; and in later years she did not even take this walk,

for the old friend was dead. In her solitude my old maid was always

busy at the window, which was adorned in summer with pretty

flowers, and in winter with cress, grown upon felt. During the last

months I saw her no more at the window, but she was still alive. I

knew that, for I had not yet seen her begin the 'long journey,' of

which she often spoke with her friend. 'Yes, yes,' she was in the

habit of saying, 'when I come to die, I shall take a longer journey

than I have made my whole life long. Our family vault is six miles

from here. I shall be carried there, and shall sleep there among my

family and relatives.' Last night a van stopped at the house. A

coffin was carried out, and then I knew that she was dead. They

placed straw round the coffin, and the van drove away. There slept

the quiet old lady, who had not gone out of her house once for the

last year. The van rolled out through the town-gate as briskly as

if it were going for a pleasant excursion. On the high-road the

pace was quicker yet. The coachman looked nervously round every now

and then—I fancy he half expected to see her sitting on the coffin,

in her yellow satin wrapper. And because he was startled, he

foolishly lashed his horses, while he held the reins so tightly

that the poor beasts were in a foam: they were young and fiery. A

hare jumped across the road and startled them, and they fairly ran

away. The old sober maiden, who had for years and years moved

quietly round and round in a dull circle, was now, in death,

rattled over stock and stone on the public highway. The coffin in

its covering of straw tumbled out of the van, and was left on the

high-road, while horses, coachman, and carriage flew past in wild

career. The lark rose up carolling from the field, twittering her

morning lay over the coffin, and presently perched upon it, picking

with her beak at the straw covering, as though she would tear it

up. The lark rose up again, singing gaily, and I withdrew behind

the red morning clouds."

Eleventh Evening."I will give you a picture of Pompeii," said the Moon. "I was

in the suburb in the Street of Tombs, as they call it, where the

fair monuments stand, in the spot where, ages ago, the merry

youths, their temples bound with rosy wreaths, danced with the fair

sisters of Laïs. Now, the stillness of death reigned around. German

mercenaries, in the Neapolitan service, kept guard, played cards,

and diced; and a troop of strangers from beyond the mountains came

into the town, accompanied by a sentry. They wanted to see the city

that had risen from the grave illumined by my beams; and I showed

them the wheel-ruts in the streets paved with broad lava slabs; I

showed them the names on the doors, and the signs that hung there

yet: they saw in the little courtyard the basins of the fountains,

ornamented with shells; but no jet of water gushed upwards, no

songs sounded forth from the richly-painted chambers, where the

bronze dog kept the door."It was the City of the Dead; only Vesuvius thundered forth

his everlasting hymn, each separate verse of which is called by men

an eruption. We went to the temple of Venus, built of snow-white

marble, with its high altar in front of the broad steps, and the

weeping willows sprouting freshly forth among the pillars. The air

was transparent and blue, and black Vesuvius formed the background,

with fire ever shooting forth from it, like the stem of the pine

tree. Above it stretched the smoky cloud in the silence of the

night, like the crown of the pine, but in a blood-red illumination.

Among the company was a lady singer, a real and great singer. I

have witnessed the homage paid to her in the greatest cities of

Europe. When they came to the tragic theatre, they all sat down on

the amphitheatre steps, and thus a small part of the house was

occupied by an audience, as it had been many centuries ago. The

stage still stood unchanged, with its walled side-scenes, and the

two arches in the background, through which the beholders saw the

same scene that had been exhibited in the old times—a scene painted

by nature herself, namely, the mountains between Sorento and

Amalfi. The singer gaily mounted the ancient stage, and sang. The

place inspired her, and she reminded me of a wild Arab horse, that

rushes headlong on with snorting nostrils and flying mane—her song

was so light and yet so firm. Anon I thought of the mourning mother

beneath the cross at Golgotha, so deep was the expression of pain.

And, just as it had done thousands of years ago, the sound of

applause and delight now filled the theatre. 'Happy, gifted

creature!' all the hearers exclaimed. Five minutes more, and the

stage was empty, the company had vanished, and not a sound more was

heard—all were gone. But the ruins stood unchanged, as they will

stand when centuries shall have gone by, and when none shall know

of the momentary applause and of the triumph of the fair

songstress; when all will be forgotten and gone, and even for me

this hour will be but a dream of the past."

Twelfth Evening."I looked through the windows of an editor's house,"

said the Moon. "It was somewhere in Germany. I saw handsome

furniture, many books, and a chaos of newspapers. Several young men

were present: the editor himself stood at his desk, and two little

books, both by young authors, were to be noticed. 'This one has

been sent to me,' said he. 'I have not read it yet; what

thinkyouof the contents?'

'Oh,' said the person addressed—he was a poet himself—'it is good

enough; a little broad, certainly; but, you see, the author is

still young. The verses might be better, to be sure; the thoughts

are sound, though there is certainly a good deal of commonplace

among them. But what will you have? You can't be always getting

something new. That he'll turn out anything great I don't believe,

but you may safely praise him. He is well read, a remarkable

Oriental scholar, and has a good judgment. It was he who wrote that

nice review of my 'Reflections on Domestic Life.' We must be

lenient towards the young man.'"'But he is a complete hack!' objected another of the

gentlemen. 'Nothing is worse in poetry than mediocrity, and he

certainly does not go beyond this.'"'Poor fellow,' observed a third, 'and his aunt is so happy

about him. It was she, Mr. Editor, who got together so many

subscribers for your last translation.'"'Ah, the good woman! Well, I have noticed the book briefly.

Undoubted talent—a welcome offering—a flower in the garden of

poetry—prettily brought out—and so on. But this other book—I

suppose the author expects me to purchase it? I hear it is praised.

He has genius, certainly; don't you think so?'"'Yes, all the world declares as much,' replied the poet,

'but it has turned out rather wildly. The punctuation of the book,

in particular, is very eccentric.'"'It will be good for him if we pull him to pieces, and anger

him a little, otherwise he will get too good an opinion of

himself.'"'But that would be unfair,' objected the fourth. 'Let us not

carp at little faults, but rejoice over the real and abundant good

that we find here: he surpasses all the rest.'"'Not so. If he is a true genius, he can bear the sharp voice

of censure. There are people enough to praise him. Don't let us

quite turn his head.'"'Decided talent,' wrote the editor, 'with the usual

carelessness. That he can write incorrect verses may be seen in

page 25, where there are two false quantities. We recommend him to

study the ancients, etc.'"I went away," continued the Moon, "and looked through

the windows in the aunt's house. There sat the be-praised poet,

thetameone; all the guests

paid homage to him, and he was happy."I sought the other poet out, thewildone; him also I found in a great

assembly at his patron's, where the tame poet's book was being

discussed."'I shall read yours also,' said Mæcenas; 'but to speak

honestly—you know I never hide my opinion from you—I don't expect

much from it, for you are much too wild, too fantastic. But it must

be allowed that, as a man, you are highly

respectable.'"A young girl sat in a corner; and she read in a book these

words:"'In the dust lies genius and glory,

But ev'ry-day talent willpay.

It's only the old, old story,

But the piece is repeated each day.'"Thirteenth Evening.The Moon said, "Beside the woodland path there are two small

farmhouses. The doors are low, and some of the windows are placed

quite high, and others close to the ground; and whitethorn and

barberry bushes grow around them. The roof of each house is

overgrown with moss and with yellow flowers and houseleek. Cabbage

and potatoes are the only plants cultivated in the gardens, but out

of the hedge there grows a willow tree, and under this willow tree

sat a little girl, and she sat with her eyes fixed upon the old oak

tree between the two huts."It was an old withered stem. It had been sawn off at the

top, and a stork had built his nest upon it; and he stood in this

nest clapping with his beak. A little boy came and stood by the

girl's side: they were brother and sister."'What are you looking at?' he asked."'I'm watching the stork,' she replied: 'our neighbours told

me that he would bring us a little brother or sister to-day; let us

watch to see it come!'"'The stork brings no such things,' the boy declared, 'you

may be sure of that. Our neighbour told me the same thing, but she

laughed when she said it, and so I asked her if she could say 'On

my honour,' and she could not; and I know by that that the story

about the storks is not true, and that they only tell it to us

children for fun.'"'But where do the babies come from, then?' asked the

girl."'Why, an angel from heaven brings them under his cloak, but

no man can see him; and that's why we never know when he brings

them.'"At that moment there was a rustling in the branches of the

willow tree, and the children folded their hands and looked at one

another: it was certainly the angel coming with the baby. They took

each other's hand, and at that moment the door of one of the houses

opened, and the neighbour appeared."'Come in, you two,' she said. 'See what the stork has

brought. It is a little brother.'"And the children nodded gravely at one another, for they had

felt quite sure already that the baby was come."

Fourteenth Evening."I was gliding over the Lüneburg Heath," the Moon said. "A

lonely hut stood by the wayside, a few scanty bushes grew near it,

and a nightingale who had lost his way sang sweetly. He died in the

coldness of the night: it was his farewell song that I

heard."The morning dawn came glimmering red. I saw a caravan of

emigrant peasant families who were bound to Hamburgh, there to take

ship for America, where fancied prosperity would bloom for them.

The mothers carried their little children at their backs, the elder

ones tottered by their sides, and a poor starved horse tugged at a

cart that bore their scanty effects. The cold wind whistled, and

therefore the little girl nestled closer to the mother, who,

looking up at my decreasing disc, thought of the bitter want at

home, and spoke of the heavy taxes they had not been able to raise.

The whole caravan thought of the same thing; therefore, the rising

dawn seemed to them a message from the sun, of fortune that was to

gleam brightly upon them. They heard the dying nightingale sing: it

was no false prophet, but a harbinger of fortune. The wind

whistled, therefore they did not understand that the nightingale

sung, 'Fare away over the sea! Thou hast paid the long passage with

all that was thine, and poor and helpless shalt thou enter Canaan.

Thou must sell thyself, thy wife, and thy children. But your griefs

shall not last long. Behind the broad fragrant leaves lurks the

goddess of Death, and her welcome kiss shall breathe fever into thy

blood. Fare away, fare away, over the heaving billows.' And the

caravan listened well pleased to the song of the nightingale, which

seemed to promise good fortune. Day broke through the light clouds;

country people went across the heath to church: the black-gowned

women with their white head-dresses looked like ghosts that had

stepped forth from the church pictures. All around lay a wide dead

plain, covered with faded brown heath, and black charred spaces

between the white sand hills. The women carried hymn books, and

walked into the church. Oh, pray, pray for those who are wandering

to find graves beyond the foaming billows."

Fifteenth Evening."I know a Pulcinella,"[3]the Moon told me. "The

public applaud vociferously directly they see him. Every one of his

movements is comic, and is sure to throw the house into convulsions

of laughter; and yet there is no art in it all—it is complete

nature. When he was yet a little boy, playing about with other

boys, he was already Punch. Nature had intended him for it, and had

provided him with a hump on his back, and another on his breast;

but his inward man, his mind, on the contrary, was richly

furnished. No one could surpass him in depth of feeling or in

readiness of intellect. The theatre was his ideal world. If he had

possessed a slender well-shaped figure, he might have been the

first tragedian on any stage: the heroic, the great, filled his

soul; and yet he had to become a Pulcinella. His very sorrow and

melancholy did but increase the comic dryness of his sharply-cut

features, and increased the laughter of the audience, who showered

plaudits on their favourite. The lovely Columbine was indeed kind

and cordial to him; but she preferred to marry the Harlequin. It

would have been too ridiculous if beauty and ugliness had in

reality paired together.[3]The comic or grotesque character of

the Italian ballet, from which the English "Punch" takes his

origin."When Pulcinella was in very bad spirits, she was the only

one who could force a hearty burst of laughter, or even a smile

from him: first she would be melancholy with him, then quieter, and

at last quite cheerful and happy. 'I know very well what is the

matter with you,' she said; 'yes, you're in love!' And he could not

help laughing. 'I and Love!' he cried, 'that would have an absurd

look. How the public would shout!' 'Certainly, you are in love,'

she continued; and added with a comic pathos, 'and I am the person

you are in love with.' You see, such a thing may be said when it is

quite out of the question—and, indeed, Pulcinella burst out

laughing, and gave a leap into the air, and his melancholy was

forgotten."And yet she had only spoken the truth. Hedidlove her, love her adoringly, as he

loved what was great and lofty in art. At her wedding he was the

merriest among the guests, but in the stillness of night he wept:

if the public had seen his distorted face then, they would have

applauded rapturously."And a few days ago, Columbine died. On the day of the

funeral, Harlequin was not required to show himself on the boards,

for he was a disconsolate widower. The director had to give a very

merry piece, that the public might not too painfully miss the

pretty Columbine and the agile Harlequin. Therefore Pulcinella had

to be more boisterous and extravagant than ever; and he danced and

capered, with despair in his heart; and the audience yelled, and

shouted 'bravo, bravissimo!'

Pulcinella was actually called before the curtain. He was

pronounced inimitable."But last night the hideous little fellow went out of

the town, quite alone, to the deserted churchyard. The wreath of

flowers on Columbine's grave was already faded, and he sat down

there. It was a study for a painter. As he sat with his chin on his

hands, his eyes turned up towards me, he looked like a grotesque

monument—a Punch on a grave—peculiar and whimsical! If the people

could have seen their favourite, they would have cried as usual,

'Bravo, Pulcinella; bravo,

bravissimo!'"

Sixteenth Evening.Hear what the Moon told me. "I have seen the cadet who had

just been made an officer put on his handsome uniform for the first

time; I have seen the young bride in her wedding dress, and the

princess girl-wife happy in her gorgeous robes; but never have I

seen a felicity equal to that of a little girl of four years old,

whom I watched this evening. She had received a new blue dress, and

a new pink hat, the splendid attire had just been put on, and all

were calling for a candle, for my rays, shining in through the

windows of the room, were not bright enough for the occasion, and

further illumination was required. There stood the little maid,

stiff and upright as a doll, her arms stretched painfully straight

out away from the dress, and her fingers apart; and oh, what

happiness beamed from her eyes, and from her whole countenance!

'To-morrow you shall go out in your new clothes,' said her mother;

and the little one looked up at her hat, and down at her frock, and

smiled brightly. 'Mother,' she cried, 'what will the little dogs

think, when they see me in these splendid new

things?'"

Seventeenth Evening."I have spoken to you of Pompeii," said the Moon; "that

corpse of a city, exposed in the view of living towns: I know

another sight still more strange, and this is not the corpse, but

the spectre of a city. Whenever the jetty fountains splash into the

marble basins, they seem to me to be telling the story of the

floating city. Yes, the spouting water may tell of her, the waves

of the sea may sing of her fame! On the surface of the ocean a mist

often rests, and that is her widow's veil. The bridegroom of the

sea is dead, his palace and his city are his mausoleum! Dost thou

know this city? She has never heard the rolling of wheels or the

hoof-tread of horses in her streets, through which the fish swim,

while the black gondola glides spectrally over the green water. I

will show you the place," continued the Moon, "the largest square

in it, and you will fancy yourself transported into the city of a

fairy tale. The grass grows rank among the broad flagstones, and in

the morning twilight thousands of tame pigeons flutter around the

solitary lofty tower. On three sides you find yourself surrounded

by cloistered walks. In these the silent Turk sits smoking his long

pipe, the handsome Greek leans against the pillar and gazes at the

upraised trophies and lofty masts, memorials of power that is gone.

The flags hang down like mourning scarves. A girl rests there: she

has put down her heavy pails filled with water, the yoke with which

she has carried them rests on one of her shoulders, and she leans

against the mast of victory. That is not a fairy palace you see

before you yonder, but a church: the gilded domes and shining orbs

flash back my beams; the glorious bronze horses up yonder have made

journeys, like the bronze horse in the fairy tale: they have come

hither, and gone hence, and have returned again. Do you notice the

variegated splendour of the walls and windows? It looks as if

Genius had followed the caprices of a child, in the adornment of

these singular temples. Do you see the winged lion on the pillar?

The gold glitters still, but his wings are tied—the lion is dead,

for the king of the sea is dead; the great halls stand desolate,

and where gorgeous paintings hung of yore, the naked wall now peers

through. Thelazzaronesleeps

under the arcade, whose pavement in old times was to be trodden

only by the feet of high nobility. From the deep wells, and perhaps

from the prisons by the Bridge of Sighs, rise the accents of woe,

as at the time when the tambourine was heard in the gay gondolas,

and the golden ring was cast from theBucentaurto Adria, the queen of the

seas. Adria! shroud thyself in mists; let the veil of thy widowhood

shroud thy form, and clothe in the weeds of woe the mausoleum of

thy bridegroom—the marble, spectral Venice."

Eighteenth Evening."I looked down upon a great theatre," said the Moon.

"The house was crowded, for a new actor was to make his first

appearance that night. My rays glided over a little window in the

wall, and I saw a painted face with the forehead pressed against

the panes. It was the hero of the evening. The knightly beard

curled crisply about the chin; but there were tears in the man's

eyes, for he had been hissed off, and indeed with reason. The poor

Incapable! But Incapables cannot be admitted into the empire of

Art. He had deep feeling, and loved his art enthusiastically, but

the art loved not him. The prompter's bell sounded; 'the hero enters with a determined air,' so ran the stage direction in his part, and he had to

appear before an audience who turned him into ridicule. When the

piece was over, I saw a form wrapped in a mantle, creeping down the

steps: it was the vanquished knight of the evening. The

scene-shifters whispered to one another, and I followed the poor

fellow home to his room. To hang one's self is to die a mean death,

and poison is not always at hand, I know; but he thought of both. I

saw how he looked at his pale face in the glass, with eyes half

closed, to see if he should look well as a corpse. A man may be

very unhappy, and yet exceedingly affected. He thought of death, of

suicide; I believe he pitied himself, for he wept bitterly, and

when a man has had his cry out he doesn't kill

himself."Since that time a year had rolled by. Again a play was to be

acted, but in a little theatre, and by a poor strolling company.

Again I saw the well-remembered face, with the painted cheeks and

the crisp beard. He looked up at me and smiled; and yet he had been

hissed off only a minute before—hissed off from a wretched theatre,

by a miserable audience. And to-night a shabby hearse rolled out of

the town-gate. It was a suicide—our painted, despised hero. The

driver of the hearse was the only person present, for no one

followed except my beams. In a corner of the churchyard the corpse

of the suicide was shovelled into the earth, and nettles will soon

be growing rankly over his grave, and the sexton will throw thorns

and weeds from the other graves upon it."

Nineteenth Evening."I come from Rome," said the Moon. "In the midst of the city,

upon one of the seven hills, lie the ruins of the imperial palace.

The wild fig tree grows in the clefts of the wall, and covers the

nakedness thereof with its broad grey-green leaves; trampling among

heaps of rubbish, the ass treads upon green laurels, and rejoices

over the rank thistles. From this spot, whence the eagles of Rome

once flew abroad, whence they 'came, saw, and conquered,' our door

leads into a little mean house, built of clay between two pillars;

the wild vine hangs like a mourning garland over the crooked

window. An old woman and her little granddaughter live there: they

rule now in the palace of the Cæsars, and show to strangers the

remains of its past glories. Of the splendid throne-hall only a

naked wall yet stands, and a black cypress throws its dark shadow

on the spot where the throne once stood. The dust lies several feet

deep on the broken pavement; and the little maiden, now the

daughter of the imperial palace, often sits there on her stool when

the evening bells ring. The keyhole of the door close by she calls

her turret window; through this she can see half Rome, as far as

the mighty cupola of St. Peter's."On this evening, as usual, stillness reigned around; and in

the full beam of my light came the little granddaughter. On her

head she carried an earthen pitcher of antique shape filled with

water. Her feet were bare, her short frock and her white sleeves

were torn. I kissed her pretty round shoulders, her dark eyes, and

black shining hair. She mounted the stairs; they were steep, having

been made up of rough blocks of broken marble and the capital of a

fallen pillar. The coloured lizards slipped away, startled, from

before her feet, but she was not frightened at them. Already she

lifted her hand to pull the door-bell—a hare's foot fastened to a

string formed the bell-handle of the imperial palace. She paused

for a moment—of what might she be thinking? Perhaps of the

beautiful Christ-child, dressed in gold and silver, which was down

below in the chapel, where the silver candlesticks gleamed so

bright, and where her little friends sung the hymns in which she

also could join? I know not. Presently she moved again—she

stumbled; the earthen vessel fell from her head, and broke on the

marble steps. She burst into tears. The beautiful daughter of the

imperial palace wept over the worthless broken pitcher; with her

bare feet she stood there weeping, and dared not pull the string,

the bell-rope of the imperial palace!"

Twentieth Evening.It was more than a fortnight since the Moon had shone. Now he

stood once more, round and bright, above the clouds, moving slowly

onward. Hear what the Moon told me."From a town in Fezzan I followed a caravan. On the margin of

the sandy desert, in a salt plain, that shone like a frozen lake,

and was only covered in spots with light drifting sand, a halt was

made. The eldest of the company—the water gourd hung at his girdle,

and on his head was a little bag of unleavened bread—drew a square

in the sand with his staff, and wrote in it a few words out of the

Koran, and then the whole caravan passed over the consecrated spot.

A young merchant, a child of the East, as I could tell by his eye

and his figure, rode pensively forward on his white snorting steed.

Was he thinking, perchance, of his fair young wife? It was only two

days ago that the camel, adorned with furs and with costly shawls,

had carried her, the beauteous bride, round the walls of the city,

while drums and cymbals had sounded, the women sang, and festive

shots, of which the bridegroom fired the greatest number, resounded

round the camel; and now he was journeying with the caravan across

the desert."For many nights I followed the train. I saw them rest by the

well-side among the stunted palms; they thrust the knife into the

breast of the camel that had fallen, and roasted its flesh by the

fire. My beams cooled the glowing sands, and showed them the black

rocks, dead islands in the immense ocean of sand. No hostile tribes

met them in their pathless route, no storms arose, no columns of

sand whirled destruction over the journeying caravan. At home the

beautiful wife prayed for her husband and her father. 'Are they

dead?' she asked of my golden crescent; 'Are they dead?' she cried

to my full disc. Now the desert lies behind them. This evening they

sit beneath the lofty palm trees, where the crane flutters round

them with its long wings, and the pelican watches them from the

branches of the mimosa. The luxuriant herbage is trampled down,

crushed by the feet of elephants. A troop of negroes are returning

from a market in the interior of the land: the women, with copper

buttons in their black hair, and decked out in clothes dyed with

indigo, drive the heavily-laden oxen, on whose backs slumber the

naked black children. A negro leads a young lion which he has

bought, by a string. They approach the caravan; the young merchant

sits pensive and motionless, thinking of his beautiful wife,

dreaming, in the land of the blacks, of his white fragrant lily

beyond the desert. He raises his head, and——" But at this moment a

cloud passed before the Moon, and then another. I heard nothing

more from him this evening.

Twenty-first Evening."I saw a little girl weeping," said the Moon; "she was

weeping over the depravity of the world. She had received a most

beautiful doll as a present. Oh, that was a glorious doll, so fair

and delicate! She did not seem created for the sorrows of this

world. But the brothers of the little girl, those great naughty

boys, had set the doll high up in the branches of a tree, and had

run away."The little girl could not reach up to the doll, and could

not help her down, and that is why she was crying. The doll must

certainly have been crying too; for she stretched out her arms

among the green branches, and looked quite mournful. Yes, these are

the troubles of life of which the little girl had often heard tell.

Alas, poor doll! it began to grow dark already; and suppose night

were to come on completely! Was she to be left sitting there alone

on the bough all night long? No, the little maid could not make up

her mind to that. 'I'll stay with you,' she said, although she felt

anything but happy in her mind. She could almost fancy she

distinctly saw little gnomes, with their high-crowned hats, sitting

in the bushes; and further back in the long walk, tall spectres

appeared to be dancing. They came nearer and nearer, and stretched

out their hands towards the tree on which the doll sat; they

laughed scornfully, and pointed at her with their fingers. Oh, how

frightened the little maid was! 'But if one has not done anything

wrong,' she thought, 'nothing evil can harm one. I wonder if I have

done anything wrong?' And she considered. 'Oh, yes! I laughed at

the poor duck with the red rag on her leg; she limped along so

funnily, I could not help laughing; but it's a sin to laugh at

animals.' And she looked up at the doll. 'Did you laugh at the duck

too?' she asked; and it seemed as if the doll shook her

head."

Twenty-second Evening."I looked down upon Tyrol," said the Moon, "and my beams

caused the dark pines to throw long shadows upon the rocks. I

looked at the pictures of St. Christopher carrying the Infant Jesus

that are painted there upon the walls of the houses, colossal

figures reaching from the ground to the roof. St. Florian was

represented pouring water on the burning house, and the Lord hung

bleeding on the great cross by the wayside. To the present

generation these are old pictures, but I saw when they were put up,

and marked how one followed the other. On the brow of the mountain

yonder is perched, like a swallow's nest, a lonely convent of nuns.

Two of the sisters stood up in the tower tolling the bell; they

were both young, and therefore their glances flew over the mountain

out into the world. A travelling coach passed by below, the

postillion wound his horn, and the poor nuns looked after the

carriage for a moment with a mournful glance, and a tear gleamed in

the eyes of the younger one. And the horn sounded faint and more

faintly, and the convent bell drowned its expiring

echoes."

Twenty-third Evening.Hear what the Moon told me. "Some years ago, here in

Copenhagen, I looked through the window of a mean little room. The

father and mother slept, but the little son was not asleep. I saw

the flowered cotton curtains of the bed move, and the child peep

forth. At first I thought he was looking at the great clock, which

was gaily painted in red and green. At the top sat a cuckoo, below

hung the heavy leaden weights, and the pendulum with the polished

disc of metal went to and fro, and said 'tick, tick.' But no, he

was not looking at the clock, but at his mother's spinning wheel,

that stood just underneath it. That was the boy's favourite piece

of furniture, but he dared not touch it, for if he meddled with it

he got a rap on the knuckles. For hours together, when his mother

was spinning, he would sit quietly by her side, watching the

murmuring spindle and the revolving wheel, and as he sat he thought

of many things. Oh, if he might only turn the wheel himself! Father

and mother were asleep; he looked at them, and looked at the

spinning wheel, and presently a little naked foot peered out of the

bed, and then a second foot, and then two little white legs. There

he stood. He looked round once more, to see if father and mother

were still asleep—yes, they slept; and now he creptsoftly,softly, in his short little nightgown,

to the spinning wheel, and began to spin. The thread flew from the

wheel, and the wheel whirled faster and faster. I kissed his fair

hair and his blue eyes, it was such a pretty

picture."At that moment the mother awoke. The curtain shook, she

looked forth, and fancied she saw a gnome or some other kind of

little spectre. 'In Heaven's name!' she cried, and aroused her

husband in a frightened way. He opened his eyes, rubbed them with

his hands, and looked at the brisk little lad. 'Why, that is

Bertel,' said he. And my eye quitted the poor room, for I have so

much to see. At the same moment I looked at the halls of the

Vatican, where the marble gods are enthroned. I shone upon the

group of the Laocoon; the stone seemed to sigh. I pressed a silent

kiss on the lips of the Muses, and they seemed to stir and move.

But my rays lingered longest about the Nile group with the colossal

god. Leaning against the Sphinx, he lies there thoughtful and

meditative, as if he were thinking on the rolling centuries; and

little love-gods sport with him and with the crocodiles. In the

horn of plenty sat with folded arms a little tiny love-god,

contemplating the great solemn river-god, a true picture of the boy

at the spinning wheel—the features were exactly the same. Charming

and life-like stood the little marble form, and yet the wheel of

the year has turned more than a thousand times since the time when

it sprang forth from the stone. Just as often as the boy in the

little room turned the spinning wheel had the great wheel murmured,

before the age could again call forth marble gods equal to those he

afterwards formed."Years have passed since all this happened," the Moon went on

to say. "Yesterday I looked upon a bay on the eastern coast of

Denmark. Glorious woods are there, and high trees, an old knightly

castle with red walls, swans floating in the ponds, and in the

background appears, among orchards, a little town with a church.

Many boats, the crews all furnished with torches, glided over the

silent expanse—but these fires had not been kindled for catching

fish, for everything had a festive look. Music sounded, a song was

sung, and in one of the boats the man stood erect to whom homage

was paid by the rest, a tall sturdy man, wrapped in a cloak. He had

blue eyes and long white hair. I knew him, and thought of the

Vatican, and of the group of the Nile, and the old marble gods. I

thought of the simple little room where little Bertel sat in his

night-shirt by the spinning wheel. The wheel of time has turned,

and new gods have come forth from the stone. From the boats there

arose a shout: 'Hurrah, hurrah for Bertel

Thorwaldsen!'"

Twenty-fourth Evening."I will now give you a picture from Frankfort," said the

Moon. "I especially noticed one building there. It was not the

house in which Goëthe was born, nor the old Council House, through

whose grated windows peered the horns of the oxen that were roasted

and given to the people when the emperors were crowned. No, it was

a private house, plain in appearance, and painted green. It stood

near the old Jews' Street. It was Rothschild's house."I looked through the open door. The staircase was

brilliantly lighted: servants carrying wax candles in massive

silver candlesticks stood there, and bowed low before an old woman,

who was being brought downstairs in a litter. The proprietor of the

house stood bare-headed, and respectfully imprinted a kiss on the

hand of the old woman. She was his mother. She nodded in a friendly

manner to him and to the servants, and they carried her into the

dark narrow street, into a little house, that was her dwelling.

Here her children had been born, from hence the fortune of the

family had arisen. If she deserted the despised street and the

little house, fortune would also desert her children. That was her

firm belief."The Moon told me no more; his visit this evening was far too

short. But I thought of the old woman in the narrow despised

street. It would have cost her but a word, and a brilliant house

would have arisen for her on the banks of the Thames—a word, and a

villa would have been prepared in the Bay of Naples."If I deserted the lowly house, where the fortunes of my sons

first began to bloom, fortune would desert them!" It was a

superstition, but a superstition of such a class, that he who knows

the story and has seen this picture, need have only two words

placed under the picture to make him understand it; and these two

words are: "A mother."

Twenty-fifth Evening.