Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

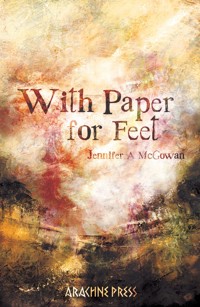

- Herausgeber: Arachne Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Drawing together Jennifer A. McGowan's poetry of myth and folktale, and the frailties – human or otherwise – behind them, With Paper for Feet explores, mostly from a female perspective, the guts it takes to live or – often – die, un-heroically. Her characters laugh, argue, complain, suffer, curse. ...Gold is heavy, and chafes.... aware that more is expected of them, but unwilling to play up. Praise for Jennifer A. McGowan's work ...gritty thought; wit; striking candour – an unafraid recognition of life's richness and desolation; memorable detail; all these are underpinned by a graceful, subtle, quite lovely way with language. Kevin Crossley-Holland ...bedecked with wit, irony, bittersweet folly and dictional-shifts jazzy enough to make a reader dance. Gray Jacobik ... precise, observant and deep into mythology. Claribel Alegría

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 54

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SECTION ONE

White Woman Walks Across China With Paper For Feet

The Talking Skull

The Witch Box

Phantom Pains

Mara Speaks

Something About Love

Song of Krampus

Love Like Salt

The Hood

In Granny’s House

Mr Fox

Bird Verdeliò

Briar Roses

Cinderella’s Mother

The Maiden Without Hands

The Horses of the Sea

Curandero

Icarus

A Sort of Love Story

SECTION TWO

Song of the Arms of a Man

Helen: Menelaus, etc.

Troy: Seven Voices

Troy: After The Horse

Pythoness

Tempus Fugue

SECTION THREE

Emilia

Lady Macbeth in Palliative Care

Cordelia in Prison

The Weird Sisters on the Make

Margaret of Anjou

Shakespeare’s Joan

Paulina as Pygmalion

His Most Famous Women

Mary Arden’s Garrets

SECTION FOUR

After the Battle

Bloody Corner

Margery Kempe

Cunning Folk

Another Witch

Nan Bullen

Listening Woman

Pharaoh’s Concubine

Dorothy King Recalls Robert Herrick, Vicar of Dean Prior

SECTION FIVE

Lilith Dreams Again of the End of Time

Mary Magdalene Walks By Another Construction Site

What History Does Not Record

Dinah

Judith and Holofernes

Pillar

Lot’s Wife Considers Reincarnation

Mortifications of the Flesh

Singing Hosanna

Secretary of God

WITH PAPER FOR FEET

SECTION ONE

WHITE WOMAN WALKS ACROSS CHINA WITH PAPER FOR FEET

Each night, the same approach to a different small house: Qĭng nĭ, yī diăn diăn fàn, diăn diăn shuĭ. Wù yào chī fàn.Please, a little rice, a little water. I need to eat. Duō xiè.Thank you. The right words coming out of my waì guó rén mouth.

Each night, setting up a bivvy against the wind, lighting a small light, writing in my journal stories, memories, forgotten names.

Sometimes I’d get lost in words, stay two or three days. Children would approach: Nĭ weìshĕnme găo cĭ a? Why do you do this?

I’d reply Wŏ de mŭ qīn chūmò wŏ, My mother haunts me, and they’d nod.

The brave would act out my need for a shrine. Sometimes where I camped, I’d leave paper ribbons, small piles of stone. Paper was the only thing to get heavier, not lighter, with use. My words, my attempt to find my mother’s birthscape, how or if I could fit into it: heavy.

Yet for all my vocabulary I could not talk, could not trade words, despite having paper for feet.

Could not send my words home, for I didn’t know where,

and what parcel box could fit all of me? Nine months of wandering, soaking my feet in flooded fields, pressing pulp to new paper, bleeding ink. White woman alone, her Chinese half never showing.

Finally at the foot of an anonymous hill my mother drifted in

with the mist. Qĭng nĭ, māmā, gĕi wŏ yī diăn diăn fàn.

Please, mother, give me something to live on. I could not see her face, but before she dissolved she spoke my name.

THE TALKING SKULL

adapted from a Nigerian folktale

A hunter

in search of food for his family

walked and walked

but found no prey.

The plains stretched on

and the sun beat

and he was weary.

There was one tree

that stretched its branches

and he sat beneath it.

Propped his feet

on a white rock

and drank.

When he was rested, he noticed

the rock had two eye-holes

and teeth. Alone

in the vast expanse

except for the sky,

he addressed the rock

in a casual fashion:

‘What brought you here, my friend?’

Then he laughed,

grateful no one could hear him.

So perhaps it is to be forgiven

if the hunter jumped

when the skull fixed him

in its empty gaze and said,

‘Talking brought me here!’

Food and family forgotten,

the hunter ran to the king

to tell him of this wonder

and the king

and all his attendants

went in stately fashion

to see the talking skull.

The plains stretched on

and the sun beat

so it is perhaps to be forgiven

if the king was weary

and rather hot and bothered

when at last they reached the one tree

that stretched its branches.

The king ordered the hunter

to show him the wonder

and the hunter found the skull

and addressed it in a friendly fashion:

‘Greetings again! Please tell my king–

what brought you here?’

But the skull

was silent.

For a long time

the hunter pleaded and implored

questioned and queried

but the skull

might well have been

a white rock to prop his feet on

for all the good it did.

The king was angry.

He had come a long way

and had expected wisdom from beyond the grave

or at least a miracle

that befit his station.

He had his champion

lop off the hunter’s head

and began the long trip home.

Beyond the one tree

the plains stretched on.

Beneath the tree

the skull rolled grinning

over to the hunter’s head and asked,

‘What brought you here, my friend?’

And the hunter’s head said sadly,

‘Talking brought me here!’

And underneath the shaded earth

other skulls set up a clattering.

THE WITCH-BOX

Hide the skin of a seal-woman. She’ll cry

of course, but she’ll marry you.

Teach her the rhythms of your day. Breakfast.

Commuting. Nightly pleasures. Teach her

to worship the sun rather than weep

at the moon’s pull. Your children will be strong,

go into a trade where there’s water. Mind

you keep some things to yourself:

shake three grains of salt from the witch-box

every night into each corner of the house;

make sure, last thing last, the skin is locked up

tighter than a shotgun. Mind, now.

If she finds it–if she slips into her unforgotten self–you’ll find

yourself ebbing; you’ll shatter the witch-box, drink only salt

wine.

PHANTOM PAINS

It happened the week after I chopped down the hawthorn.

A knife-slip, a welter of blood, and time shifts.

Woollen clothes, straw prickling my skin, I moan

in a smoky half-light. A beldame crouches at my feet,

encouraging me to breathe. (This is the time

I die in childbirth. My husband is a woodcutter.)

A hundred years later, my brother is taken by fairies.

Mother and Father talk in whispers through the night,

and Mother cries. My best enemy, Jennet Clark,

tells me he’s run off to sea, or to London–the story

changes with each telling; the important thing is

he doesn’t want us, and that it hurts–but Father

hangs horseshoes, and buries a witch-bottle

under the threshold for good measure.

When the next baby is a girl,

and she deformed, even Jennet is silenced. Father

cuts down a stand of thorn in revenge. I go to town